Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Heirs of Suguitan

Caricato da

Kitkat Ayala0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

28 visualizzazioni8 pagineHeirs of Suguitan

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

DOCX, PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoHeirs of Suguitan

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato DOCX, PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

28 visualizzazioni8 pagineHeirs of Suguitan

Caricato da

Kitkat AyalaHeirs of Suguitan

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato DOCX, PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 8

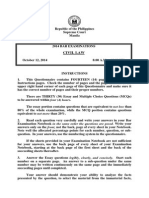

VOL.

328, MARCH 14, 2000

137

Heirs of Alberto Suguitan vs. City of Mandaluyong

G.R. No. 135087. March 14, 2000.*

HEIRS OF ALBERTO SUGUITAN, petitioners, vs.

CITY OF MANDALUYONG, respondent.

Constitutional Law; Eminent Domain; Eminent

domain is the right or power of a sovereign state to

appropriate private property to particular uses to

promote public welfare.Eminent domain is the

right or power of a sovereign state to appropriate

private property to particular uses to promote public

welfare. It is an indispensable attribute of

sovereignty; a power grounded in the primary duty

of government to serve the common need and

advance the general welfare. Thus, the right of

eminent domain appertains to every independent

government without the necessity for constitutional

_______________

* THIRD DIVISION.

138

138

SUPREME COURT REPORTS ANNOTATED

Heirs of Alberto Suguitan vs. City of Mandaluyong

recognition. The provisions found in modern

constitutions of civilized countries relating to the

taking of property for the public use do not by

implication grant the power to the government, but

limit a power which would otherwise be without

limit. Thus, our own Constitution provides that

[p]rivate property shall not be taken for public use

without just compensation. Furthermore, the due

process and equal protection clauses act as additional

safeguards against the arbitrary exercise of this

governmental power.

Same; Same; The power of eminent domain may be

validly delegated to local government units, other

public entities and public utilities.The power of

eminent domain is essentially legislative in nature. It

is firmly settled, however, that such power may be

validly delegated to local government units, other

public entities and public utilities, although the scope

of this delegated legislative power is necessarily

narrower than that of the delegating authority and

may only be exercised in strict compliance with the

terms of the delegating law.

Same; Same; Despite the existence of this legislative

grant in favor of local governments, it is still the duty

of the courts to determine whether the power of

eminent domain is being exercised in accordance with

the delegating law.Despite the existence of this

legislative grant in favor of local governments, it is

still the duty of the courts to determine whether the

power of eminent domain is being exercised in

accordance with the delegating law. In fact, the courts

have adopted a more censorious attitude in resolving

questions involving the proper exercise of this

delegated power by local bodies, as compared to

instances when it is directly exercised by the national

legislature.

Same; Same; Requisites to be complied with by the

local government unit in the exercise of the power of

eminent domain.The courts have the obligation to

determine whether the following requisites have been

complied with by the local government unit

concerned: 1. An ordinance is enacted by the local

legislative council authorizing the local chief

executive, in behalf of the local government unit, to

exercise the power of eminent domain or pursue

expropriation proceedings over a particular private

property. 2. The power of eminent domain is

exercised for public use, purpose or welfare, or for

the benefit of the poor and the landless. 3. There is

payment of just compensation, as required under

Section 9, Article III of the Constitution, and other

pertinent laws. 4. A valid and

139

VOL. 328, MARCH 14, 2000

139

Heirs of Alberto Suguitan vs. City of Mandaluyong

definite offer has been previously made to the owner

of the property sought to be expropriated, but said

offer was not accepted.

Same; Same; An ordinance, not a resolution, is

required for the exercise of the power of eminent

domain.In the present case, the City of

Mandaluyong seeks to exercise the power of eminent

domain over petitioners property by means of a

resolution, in contravention of the first requisite. The

law in this case is clear and free from ambiguity.

Section 19 of the Code requires an ordinance, not a

resolution, for the exercise of the power of eminent

domain.

Same; Same; An ordinance promulgated by the local

legislative body authorizing its local chief executive

to exercise the power of eminent domain is necessary

prior to the filing by the latter of the complaint with

the proper court.It is noted that as soon as the

complaint is filed the plaintiff shall already have the

right to enter upon the possession of the real property

involved upon depositing with the court at least

fifteen percent (15%) of the fair market value of the

property based on the current tax declaration of the

property to be expropriated. Therefore, an ordinance

promulgated by the local legislative body authorizing

its local chief executive to exercise the power of

eminent domain is necessary prior to the filing by the

latter of the complaint with the proper court, and not

only after the court has determined the amount of just

compensation to which the defendant is entitled.

PETITION for review on certiorari of a decision of the

Regional Trial Court of Pasig City, Br. 155.

The facts are stated in the opinion of the Court.

Marius Corpus for petitioners.

Roberto L. Lim and Jimmy D. Lacebal for

respondent.

GONZAGA-REYES, J.:

In this petition for review on certiorari under Rule 45,

petitioners1 pray for the reversal of the Order dated

July 28, 1998

________________

1 Alberto Suguitan passed away on October 2, 1998.

On November 25, 1998 the Court allowed the heirs of

Alberto Suguitan to substitute the latter as petitioner.

140

140

SUPREME COURT REPORTS ANNOTATED

Heirs of Alberto Suguitan vs. City of Mandaluyong

issued by Branch 155 of the Regional Trial Court of

Pasig in SCA No. 875 entitled City of Mandaluyong

v. Alberto S. Suguitan, the dispositive portion of

which reads as follows:

WHEREFORE, in view of the foregoing, the instant

Motion to Dismiss is hereby DENIED and an ORDER

OF CONDEMNATION is hereby issued declaring

that the plaintiff, City of Mandaluyong, has a lawful

right to take the subject parcel of land together with

existing improvements thereon more specifically

covered by Transfer Certificate Of Title No. 56264 of

the Registry of Deeds for Metro Manila District II for

the public use or purpose as stated in the Complaint,

upon payment of just compensation.

Accordingly, in order to ascertain the just

compensation, the parties are hereby directed to

submit to the Court within fifteen (15) days from

notice hereof, a list of independent appraisers from

which the Court will select three (3) to be appointed

as Commissioners, pursuant to Section 5, Rule 67,

Rules of Court.

SO ORDERED.2

It is undisputed by the parties that on October 13,

1994, the Sangguniang Panlungsod of Mandaluyong

City issued Resolution No. 396, S-19943 authorizing

then Mayor Benjamin

_________________

2 Rollo, 17-18.

3

REPUBLIKA NG PILIPINAS

SANGGUNIANG PANLUNGSOD

Lungsod Ng Mandaluyong

RESOLUTION NO. 396, S-1994

RESOLUTION AUTHORIZING MAYOR BENJAMIN

S. ABALOS TO INITIATE AND INSTITUTE

APPROPRIATE STEPS TO EFFECT THE

EXPROPRIATION OF THAT PARCEL OF LAND

COVERED BY TRANSFER CERTIFICATE OF TITLE

NO. 56264.

BE IT APPROVED by the Sangguniang Panlungsod

of the City of Mandaluyong in session assembled:

WHEREAS, the daily influx of patients to the

Mandaluyong Medical Center has considerably

increased to a point that it could not accommodate

some more.

141

VOL. 328, MARCH 14, 2000

141

Heirs of Alberto Suguitan vs. City of Mandaluyong

S. Abalos to institute expropriation proceedings over

the property of Alberto Suguitan located at Boni

Avenue and Sto.

___________________

WHEREAS, as the Mandaluyong Medical Center is

the only institution that delivers health and medical

services for free to the less fortunate residents of the

City of Mandaluyong, it is imperative that

appropriate steps be undertaken in order that those

that need its services may be accommodated.

WHEREAS, adjacent to the Mandaluyong Medical

Center is a two storey building erected on a parcel of

land covered by Transfer Certificate of Title No. 56264

of the Registry of Deeds for Mandaluyong Branch.

WHEREAS, above structure and the land upon which

the same is erected is very ideal for the projected

expansion of the Mandaluyong Medical Center in

order that it may continue to serve a greater number

of less fortunate residents of the City.

WHEREAS, and it appearing that the owner of the

above property is not desirous of selling the same

even under reasonable terms and conditions, there is

a need that the power of eminent domain be

exercised by the City Government in order that public

health and welfare may continuously be served in a

proper and suitable manner.

NOW, THEREFORE, upon motion duly seconded,

the Sangguniang Panlungsod, RESOLVED, as it

hereby RESOLVES, to authorize, as Mayor Benjamin

S. Abalos is hereby authorized, to initiate and

institute appropriate action for the expropriation of

the property covered by Transfer Certificate of Title

No. 56264 of the Registry of Deeds for Mandaluyong

Branch, including the improvements erected thereon

in order that the proposed expansion of the

Mandaluyong Medical Center may be implemented.

ADOPTED on this 13th day of October, 1994, at the

City of Mandaluyong.

I HEREBY CERTIFY THAT THE FOREGOING

RESOLUTION WAS ADOPTED AND APPROVED

BY THE SANGGUNIANG PANLUNGSOD OF

MANDALUYONG IN REGULAR SESSION HELD

ON THE DATE AND PLACE FIRST ABOVE GIVEN.

(sgd.)

WILLIARD S. WONG

Sanggunian Secretary

142

142

SUPREME COURT REPORTS ANNOTATED

Heirs of Alberto Suguitan vs. City of Mandaluyong

Rosario streets in Mandaluyong City with an area of

414square meters and more particularly described

under Transfer Certificate of Title No. 56264 of the

Registry of Deeds ofMetro Manila District II. The

intended purpose of the expropriation was the

expansion of the Mandaluyong Medical Center.

Mayor Benjamin Abalos wrote Alberto Suguitan a

letter dated January 20, 1995 offering to buy his

property, but Suguitan refused to sell.4

Consequently, on March 13, 1995, the city of

Mandaluyong filed a complaint5 for expropriation

with the Regional Trial Court of Pasig. The case was

docketed as SCA No. 875.

Suguitan filed a motion to dismiss6 the complaint

based on the following grounds(1) the power of

eminent domain is not being exercised in accordance

with law; (2) there is no public necessity to warrant

expropriation of subject property; (3) the City of

Mandaluyong seeks to expropriate the said property

without payment of just compensation; (4) the City of

Mandaluyong has no budget and appropriation for

the payment of the property being expropriated; and

(5) expropriation of Suguitans property is but a ploy

of Mayor Benjamin Abalos to acquire the same for his

personal use. Respondent filed its comment and

opposition to the motion. On October 24, 1995, the

trial court denied Suguitans motion to dismiss.7

On November 14, 1995, acting upon a motion filed by

the respondent, the trial court issued an order

allowing the City of Mandaluyong to take immediate

possession of Suguitans

__________________

ATTESTED:

APPROVED:

(sgd.)

(sgd.)

RAMON M. GUZMAN

BENJAMIN S. ABALOS

Vice-Mayor

Mayor

Presiding Officer

On: OCT. 19, 1994

4 Rollo, 59.

5 Ibid., 20-25.

6 Ibid., 26-37.

7 Ibid., 60; RTC Records, 86.

143

VOL. 328, MARCH 14, 2000

143

Heirs of Alberto Suguitan vs. City of Mandaluyong

property upon the deposit of P621,000 representing

15% of the fair market value of the subject property

based upon the current tax declaration of such

property. On December 15, 1995, the City of

Mandaluyong assumed possession of the subject

property by virtue of a writ of possession issued by

the trial court on December 14, 1995.8 On July 28,

1998, the court granted the assailed order of

expropriation.

Petitioners assert that the city of Mandaluyong may

only exercise its delegated power of eminent domain

by means of an ordinance as required by section 19 of

Republic Act (RA) No. 7160,9 and not by means of a

mere resolution.10 Respondent contends, however,

that it validly and legally exercised its power of

eminent domain; that pursuant to article 36, Rule VI

of the Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRR) of

RA 7160, a resolution is a sufficient antecedent for the

filing of expropriation proceedings with the Regional

Trial Court. Respondents position, which was

upheld by the trial court, was explained, thus:11

. . . in the exercise of the respondent City of

Mandaluyongs power of eminent domain, a

resolution empowering the City Mayor to initiate

such expropriation proceedings and thereafter when

the court has already determine[d] with certainty the

amount of just compensation to be paid for the

property expropriated, then follows an Ordinance of

the Sanggunian Panlungsod appropriating funds for

the payment of the expropriated property.

Admittedly, title to the property expropriated shall

pass from the owner to the expropriator only upon

full payment of the just compensation.12

Petitioners refute respondents contention that only a

resolution is necessary upon the initiation of

expropriation proceedings and that an ordinance is

required only in order to

________________

8 Ibid., 60-62.

9 Otherwise known as the Local Government Code

of 1991 (hereinafter, [the] Code).

10 Rollo, 8.

11 Ibid., 15.

12 Ibid., 50-51.

144

144

SUPREME COURT REPORTS ANNOTATED

Heirs of Alberto Suguitan vs. City of Mandaluyong

appropriate the funds for the payment of just

compensation, explaining that the resolution

mentioned in article 36 of the IRR is for purposes of

granting administrative authority to the local chief

executive to file the expropriation case in court and to

represent the local government unit in such case, but

does not dispense with the necessity of an ordinance

for the exercise of the power of eminent domain

under section 19 of the Code.13

The petition is imbued with merit.

Eminent domain is the right or power of a sovereign

state to appropriate private property to particular

uses to promote public welfare.14 It is an

indispensable attribute of sovereignty; a power

grounded in the primary duty of government to serve

the common need and advance the general welfare.15

Thus, the right of eminent domain appertains to

every independent government without the necessity

for constitutional recognition.16 The provisions found

in modern constitutions of civilized countries relating

to the taking of property for the public use do not by

implication grant the power to the government, but

limit a power which would otherwise be without

limit.17 Thus, our own Constitution provides that

[p]rivate property shall not be taken for public use

without just compensation.18 Furthermore, the due

process and equal protection clauses19 act as

additional safeguards against the arbitrary exercise of

this governmental power.

________________

13 Ibid., 10.

14 Jeffress v. Town of Greenville, 70 S.E. 919, 921, 154

N.C. 490, cited in Words and Phrases, vol. 14, p. 469

(1952).

15 Ryan v. Housing Authority of City of Newark, 15

A.2d 647, 650, 125 N.J.L., 336.

16 Schrader v. Third Judicial Dist. Court in and for

Eureka County, 73 P.2d 493, 495, 58 Nev. 188.

17 Visayan Refining Co. v. Camus and Paredes, 40

Phil. 550 (1919).

18 Art. III, sec. 9.

19 1987 Constitution, art. III, sec. 1.

145

VOL. 328, MARCH 14, 2000

145

Heirs of Alberto Suguitan vs. City of Mandaluyong

Since the exercise of the power of eminent domain

affects an individuals right to private property, a

constitutionally-protected right necessary for the

preservation and enhancement of personal dignity

and intimately connected with the rights to life and

liberty,20 the need for its circumspect operation

cannot be overemphasized. In City of Manila vs.

Chinese Community of Manila we said:21

The exercise of the right of eminent domain, whether

directly by the State, or by its authorized agents, is

necessarily in derogation of private rights, and the

rule in that case is that the authority must be strictly

construed. No species of property is held by

individuals with greater tenacity, and none is

guarded by the constitution and the laws more

sedulously, than the right to the freehold of

inhabitants. When the legislature interferes with that

right, and, for greater public purposes, appropriates

the land of an individual without his consent, the

plain meaning of the law should not be enlarged by

doubt[ful] interpretation. (Bensley vs. Mountainlake

Water Co., 13 Cal., 306 and cases cited [73 Am. Dec,

576].)

The statutory power of taking property from the

owner without his consent is one of the most delicate

exercise of governmental authority. It is to be

watched with jealous scrutiny. Important as the

power may be to the government, the inviolable

sanctity which all free constitutions attach to the right

of property of the citizens, constrains the strict

observance of the substantial provisions of the law

which are prescribed as modes of the exercise of the

power, and to protect it from abuse . . . . (Dillon on

Municipal Corporations [5th Ed.], sec. 1040, and cases

cited; Tenorio vs. Manila Railroad Co., 22 Phil., 411.)

The power of eminent domain is essentially

legislative in nature. It is firmly settled, however, that

such power may be validly delegated to local

government units, other public entities and public

utilities, although the scope of this delegated

legislative power is necessarily narrower than that of

the

________________

20 Joaquin G. Bernas, The Constitution of the

Republic of the Philippines: A Commentary, vol. 1, p.

43 (1987).

21 40 Phil. 349 (1919).

146

146

SUPREME COURT REPORTS ANNOTATED

Heirs of Alberto Suguitan vs. City of Mandaluyong

delegating authority and may only be exercised in

strict compliance with the terms of the delegating

law.22 The basis for the exercise of the power of

eminent domain by local government units is section

19 of RA 7160 which provides that:

A local government unit may, through its chief

executive and acting pursuant to an ordinance,

exercise the power of eminent domain for public use,

purpose, or welfare for the benefits of the poor and

the landless, upon payment of just compensation,

pursuant to the provisions of the Constitution and

pertinent laws; Provided, however, That the power of

eminent domain may not be exercised unless a valid

and definite offer has been previously made to the

owner, and such offer was not accepted; Provided,

further, That the local government unit may

immediately take possession of the property upon the

filing of the expropriation proceedings and upon

making a deposit with the proper court of at least

fifteen percent (15%) of the fair market value of the

property based on the current tax declaration of the

property to be expropriated; Provided, finally, That

the amount to be paid for the expropriated property

shall be determined by the proper court, based on the

fair market value at the time of the taking of the

property.

Despite the existence of this legislative grant in favor

of local governments, it is still the duty of the courts

to determine whether the power of eminent domain

is being exercised in accordance with the delegating

law.23 In fact, the courts have adopted a more

censorious attitude in resolving questions involving

the proper exercise of this delegated power by local

bodies, as compared to instances when it is directly

exercised by the national legislature.24

________________

22 City of Manila v. Chinese Community of Manila,

id.; Moday v. Court of Appeals, 268 SCRA 586 (1997).

23 City of Manila v. Chinese Community of Manila,

id.

24 Isagani A. Cruz, Constitutional Law, p. 62 (1991);

See also Republic of the Philippines v. La Orden de

PO. Benedictinos de Filipinas, 1 SCRA 649 (1961);

City of Manila v. Chinese Community of Manila, id.

147

VOL. 328, MARCH 14, 2000

147

Heirs of Alberto Suguitan vs. City of Mandaluyong

The courts have the obligation to determine whether

the following requisites have been complied with by

the local government unit concerned:

1. An ordinance is enacted by the local legislative

council authorizing the local chief executive, in behalf

of the local government unit, to exercise the power of

eminent domain or pursue expropriation proceedings

over a particular private property.

2. The power of eminent domain is exercised for

public use, purpose or welfare, or for the benefit of

the poor and the landless.

3. There is payment of just compensation, as required

under Section 9, Article III of the Constitution, and

other pertinent laws.

4. A valid and definite offer has been previously

made to the owner of the property sought to be

expropriated, but said offer was not accepted.25

In the present case, the City of Mandaluyong seeks to

exercise the power of eminent domain over

petitioners property by means of a resolution, in

contravention of the first requisite. The law in this

case is clear and free from ambiguity. Section 19 of

the Code requires an ordinance, not a resolution, for

the exercise of the power of eminent domain. We

reiterate our ruling in Municipality of Paraaque v.

V.M. Realty Corporation26 regarding the distinction

between an ordinance and a resolution. In that 1998

case we held that:

We are not convinced by petitioners insistence that

the terms resolution and ordinance are

synonymous. A municipal ordinance is different from

a resolution. An ordinance is a law, but a resolution is

merely a declaration of the sentiment or opinion of a

lawmaking body on a specific matter. An ordinance

possesses a general and permanent character, but a

resolution is temporary in nature. Additionally, the

two are enacted differentlya third reading is

necessary for an ordinance, but not for a resolution,

unless decided otherwise by a majority of all the

Sanggunian members.

__________________

25 Municipality of Paraaque v. V.M. Realty

Corporation, 292 SCRA 678 [1998].

26 Id.

148

148

SUPREME COURT REPORTS ANNOTATED

Heirs of Alberto Suguitan vs. City of Mandaluyong

We cannot uphold respondents contention that an

ordinance is needed only to appropriate funds after

the court has determined the amount of just

compensation. An examination of the applicable law

will show that an ordinance is necessary to authorize

the filing of a complaint with the proper court since,

beginning at this point, the power of eminent domain

is already being exercised.

Rule 67 of the 1997 Revised Rules of Court reveals

that expropriation proceedings are comprised of two

stages:

(1) the first is concerned with the determination of the

authority of the plaintiff to exercise the power of

eminent domain and the propriety of its exercise in

the context of the facts involved in the suit; it ends

with an order, if not in a dismissal of the action, of

condemnation declaring that the plaintiff has a lawful

right to take the property sought to be condemned,

for the public use or purpose described in the

complaint, upon the payment of just compensation to

be determined as of the date of the filing of the

complaint;

(2) the second phase is concerned with the

determination by the court of the just compensation

for the property sought to be taken; this is done by

the court with the assistance of not more than three

(3) commissioners.27

Clearly, although the determination and award of just

compensation to the defendant is indispensable to the

transfer of ownership in favor of the plaintiff, it is but

the last stage of the expropriation proceedings, which

cannot be arrived at without an initial finding by the

court that the plaintiff has a lawful right to take the

property sought to be expropriated, for the public use

or purpose described in the complaint. An order of

condemnation or dismissal at this stage would be

final, resolving the question of whether or not the

plaintiff has properly and legally exercised its power

of eminent domain.

_______________

27 National Power Corporation v. Jocson, 206 SCRA

520 (1992), citing Municipality of Bian v. Garcia, 180

SCRA 576 (1989).

149

VOL. 328, MARCH 14, 2000

149

Heirs of Alberto Suguitan vs. City of Mandaluyong

Also, it is noted that as soon as the complaint is filed

the plaintiff shall already have the right to enter upon

the possession of the real property involved upon

depositing with the court at least fifteen percent (15%)

of the fair market value of the property based on the

current tax declaration of the property to be

expropriated.28 Therefore, an ordinance promulgated

by the local legislative body authorizing its local chief

executive to exercise the power of eminent domain is

necessary prior to the filing by the latter of the

complaint with the proper court, and not only after

the court has determined the amount of just

compensation to which the defendant is entitled.

Neither is respondents position improved by its

reliance upon Article 36(a), Rule VI of the IRR which

provides that:

If the LGU fails to acquire a private property for

public use, purpose, or welfare through purchase,

LGU may expropriate said property through a

resolution of the sanggunian authorizing its chief

executive to initiate expropriation proceedings.

The Court has already discussed this inconsistency

between the Code and the IRR, which is more

apparent than real, in Municipality of Paraaque vs.

V.M. Realty Corporation,29 which we quote

hereunder:

Petitioner relies on Article 36, Rule VI of the

Implementing Rules, which requires only a resolution

to authorize an LGU to exercise eminent domain. This

is clearly misplaced, because Section 19 of RA 7160,

the law itself, surely prevails over said rule which

merely seeks to implement it. It is axiomatic that the

clear letter of the law is controlling and cannot be

amended by a mere administrative rule issued for its

implementation. Besides, what the discrepancy seems

to indicate is a mere oversight in the wording of the

implementing rules, since Article 32, Rule VI thereof,

also requires that, in exercising the power of eminent

domain, the chief executive of the LGU must act

pursuant to an ordinance.

_______________

28 Code, sec. 19.

29 Supra note 25.

150

150

SUPREME COURT REPORTS ANNOTATED

Heirs of Alberto Suguitan vs. City of Mandaluyong

Therefore, while we remain conscious of the

constitutional policy of promoting local autonomy,

we cannot grant judicial sanction to a local

government units exercise of its delegated power of

eminent domain in contravention of the very law

giving it such power.

It should be noted, however, that our ruling in this

case will not preclude the City of Mandaluyong from

enacting the necessary ordinance and thereafter

reinstituting expropriation proceedings, for so long as

it has complied with all other legal requirements.30

WHEREFORE, the petition is hereby GRANTED. The

July 28, 1998 decision of Branch 155 of the Regional

Trial Court of Pasig in SCA No. 875 is hereby

REVERSED and SET ASIDE.

SO ORDERED.

Melo (Chairman), Vitug, Panganiban and

Purisima, JJ., concur.

Petition granted, judgment reversed and set aside.

Note.Inherently possessed by the national

legislature, the power of eminent domain may be

validly delegated to local governments, other public

entities and public utilities. (Moday vs. Court of

Appeals, 268 SCRA 586 [1997])

o0o

_____________

30 Id.

151

Copyright 2014 Central Book Supply, Inc. All rights

reserved. [Heirs of Alberto Suguitan vs. City of

Mandaluyong, 328 SCRA 137(2000)]

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- CaseDocumento29 pagineCaseKitkat AyalaNessuna valutazione finora

- Goin and OutDocumento1 paginaGoin and OutKitkat AyalaNessuna valutazione finora

- CrisisDocumento1 paginaCrisisKitkat AyalaNessuna valutazione finora

- CaseDocumento29 pagineCaseKitkat AyalaNessuna valutazione finora

- Bar 2016 Petition FormDocumento6 pagineBar 2016 Petition FormRoxan Desiree T. Ortaleza-TanNessuna valutazione finora

- Rowrowrowyour BoatDocumento1 paginaRowrowrowyour Boatapi-3728690Nessuna valutazione finora

- Rowrowrowyour BoatDocumento1 paginaRowrowrowyour Boatapi-3728690Nessuna valutazione finora

- 1love Is More Thicker Than ForgetDocumento1 pagina1love Is More Thicker Than ForgetKitkat AyalaNessuna valutazione finora

- Edgar Allan PoeDocumento1 paginaEdgar Allan PoeKitkat AyalaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2014 Bar Civil LawDocumento14 pagine2014 Bar Civil LawAries BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- How Happy Is The Little StoneDocumento1 paginaHow Happy Is The Little StoneKitkat AyalaNessuna valutazione finora

- Mercantile Law 2013 October Bar ExamsDocumento17 pagineMercantile Law 2013 October Bar ExamsNeil RiveraNessuna valutazione finora

- UST GN 2011 - Labor Law ProperDocumento191 pagineUST GN 2011 - Labor Law ProperGhost100% (8)

- Digest of Laguna Lake Development Authority v. CA (G.R. Nos. 120865-71)Documento4 pagineDigest of Laguna Lake Development Authority v. CA (G.R. Nos. 120865-71)Rafael Pangilinan100% (7)

- San Juan Vs CastroDocumento3 pagineSan Juan Vs CastroKitkat AyalaNessuna valutazione finora

- LaborDocumento2 pagineLaborKitkat AyalaNessuna valutazione finora

- LaborDocumento2 pagineLaborKitkat AyalaNessuna valutazione finora

- I Am Not Yours: by Sara TeasdaleDocumento1 paginaI Am Not Yours: by Sara TeasdaleKitkat AyalaNessuna valutazione finora

- Def TermsDocumento1 paginaDef TermsKitkat AyalaNessuna valutazione finora

- 1love Is More Thicker Than ForgetDocumento1 pagina1love Is More Thicker Than ForgetKitkat AyalaNessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento1 paginaUntitledMaria Lorena FabiañaNessuna valutazione finora

- UST GN 2011 - Civil Law IndexDocumento3 pagineUST GN 2011 - Civil Law IndexGhostNessuna valutazione finora

- His Excuse For LovingDocumento1 paginaHis Excuse For LovingKitkat AyalaNessuna valutazione finora

- A Lover's Complaint - ShakespeareDocumento9 pagineA Lover's Complaint - ShakespeareKitkat AyalaNessuna valutazione finora

- 666Documento12 pagine666Kitkat AyalaNessuna valutazione finora

- Shakespeare On LawyersDocumento2 pagineShakespeare On LawyersKitkat AyalaNessuna valutazione finora

- Dulce Et Decorum Est: Pro Patria MoriDocumento2 pagineDulce Et Decorum Est: Pro Patria MorimarceloNessuna valutazione finora

- Emily BronteDocumento1 paginaEmily BronteKitkat AyalaNessuna valutazione finora

- A Lover's Complaint - ShakespeareDocumento9 pagineA Lover's Complaint - ShakespeareKitkat AyalaNessuna valutazione finora

- Forensic Ballistics KargerDocumento34 pagineForensic Ballistics KargerKitkat Ayala100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- 1 Sources of LawDocumento23 pagine1 Sources of Lawapi-2415052580% (1)

- Special Power of Attorney: HEREBY GIVING AND GRANTING Unto My Said Attorney-In-Fact Full PowerDocumento3 pagineSpecial Power of Attorney: HEREBY GIVING AND GRANTING Unto My Said Attorney-In-Fact Full PowerMarie Charlotte OlondrizNessuna valutazione finora

- Lawphil - G.R. NO. 122646 MARCH 14, 1997Documento4 pagineLawphil - G.R. NO. 122646 MARCH 14, 1997ailynvdsNessuna valutazione finora

- Case 122. Hutchinson Ports v. SBMA (2000)Documento5 pagineCase 122. Hutchinson Ports v. SBMA (2000)angelo doceoNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Justice Society v. Atienza, Jr.Documento5 pagineSocial Justice Society v. Atienza, Jr.Noreenesse Santos100% (1)

- People Vs AntonioDocumento7 paginePeople Vs AntoniostrgrlNessuna valutazione finora

- 46 Estate of Ong Vs DiazDocumento2 pagine46 Estate of Ong Vs DiazLeica JaymeNessuna valutazione finora

- Quoted Hereunder, For Your Information, Is A Resolution of The Court en Banc Dated AprilDocumento130 pagineQuoted Hereunder, For Your Information, Is A Resolution of The Court en Banc Dated AprilDheimEresNessuna valutazione finora

- Comparative Public Law Project - Aachman ShekharDocumento15 pagineComparative Public Law Project - Aachman ShekharadvocateanujmalikNessuna valutazione finora

- Lumen View Technology v. CatchafireDocumento6 pagineLumen View Technology v. CatchafirePriorSmartNessuna valutazione finora

- People v. YabutDocumento3 paginePeople v. YabutChristine Sumaway100% (1)

- Buccat V Buccat 72 Phil. 19 (1941)Documento1 paginaBuccat V Buccat 72 Phil. 19 (1941)Jr Dela Cerna100% (2)

- Chuidian v. Sandiganbayan Case DigestDocumento2 pagineChuidian v. Sandiganbayan Case Digestalbemart100% (2)

- Hans Raj vs. State of Haryana (26.02.2004 - SC)Documento4 pagineHans Raj vs. State of Haryana (26.02.2004 - SC)tarun chhapolaNessuna valutazione finora

- CIV Case DigestDocumento86 pagineCIV Case DigestvalkyriorNessuna valutazione finora

- Actual Case - Habeas CorpusDocumento46 pagineActual Case - Habeas Corpusmaanyag6685Nessuna valutazione finora

- Canlas V CADocumento9 pagineCanlas V CABrian TomasNessuna valutazione finora

- Chua vs. Court of Appeals and HaoDocumento3 pagineChua vs. Court of Appeals and HaoChristian Rize NavasNessuna valutazione finora

- Tan Vs CincoDocumento3 pagineTan Vs CincoAnonymous admm2tlYNessuna valutazione finora

- EC Tattler #35Documento2 pagineEC Tattler #35Eric J BrewerNessuna valutazione finora

- Iphigenia in Forest Hills AnatomyDocumento166 pagineIphigenia in Forest Hills AnatomyquoroNessuna valutazione finora

- United States v. Shively, 10th Cir. (2001)Documento6 pagineUnited States v. Shively, 10th Cir. (2001)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- CAUNCA vs. SALAZAR PDFDocumento35 pagineCAUNCA vs. SALAZAR PDFKristela AdraincemNessuna valutazione finora

- Hark Defendant Assigning Memo - 2019Documento4 pagineHark Defendant Assigning Memo - 2019St GaNessuna valutazione finora

- 6 Vikas Sud ABDocumento15 pagine6 Vikas Sud ABkrishanNessuna valutazione finora

- Garber v. MLB Settlement AgreementDocumento30 pagineGarber v. MLB Settlement Agreementngrow9Nessuna valutazione finora

- Saludaga vs. SandiganbayanDocumento7 pagineSaludaga vs. SandiganbayanAnakataNessuna valutazione finora

- Fraud On The Court As A Basis For Dismissal With Prejudice or Default - An Old Remedy Has New Teeth - The Florida BarDocumento7 pagineFraud On The Court As A Basis For Dismissal With Prejudice or Default - An Old Remedy Has New Teeth - The Florida BarJohnnyLarson100% (1)

- Junquera vs. BorromeoDocumento6 pagineJunquera vs. BorromeoAngelReaNessuna valutazione finora

- Premiere Development Bank V FloresDocumento3 paginePremiere Development Bank V FloresLUNANessuna valutazione finora