Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Sophias Choice KQ

Caricato da

NhâtTân0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

11 visualizzazioni5 pagineDr.Stephen Krashen

Titolo originale

Sophias Choice Kq

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoDr.Stephen Krashen

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

11 visualizzazioni5 pagineSophias Choice KQ

Caricato da

NhâtTânDr.Stephen Krashen

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 5

Sophias Choice: Summer Reading

Shu-Yuan Lin, Fay Shin, and Stephen Krashen

Knowledge Quest, volume 4, (March/April), 2007

I really enjoy reading when there are no strings attached, when there is no book

report or assignment . I also like the freedom of choosing any book I wish to

read. I believe that people would read a lot more if they find books they are

fascinated by. No pressure of doing well on an assignment, but the pleasure of

reading I know when I find a book I like. I just cant put it aside. On the other

hand, when I am being forced to read, I lose interest instantly. Sophia.

Sophia is the teenage daughter in a family of middle class immigrants from

Taiwan. The family arrived in the US when Sophia was in grade six; at the time

she had only minimal English, the result of private lessons several days per week

for two years.

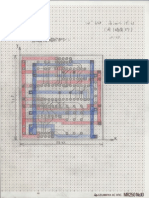

After entering grade eight, Sophia was tested in English reading on the Idaho

Standards Achievement Test (ISAT) each year in the fall and in the spring. At

first glance, things dont look good: As shown in table one, Sophias scores

actually drop each year. She dropped 29 percentiles during grade 8, 21 percentiles

during grade 9, and another 21 percentiles during grade 10. It seems that Sophia

was falling behind her classmates each year, a student who was clearly in trouble.

Table 1: Sophias Decline During the School Year

acad yr drop in % ile

gr 8:02-03 29

gr 9:03-04 21

gr 10: 04-05 21

But Sophia was not in trouble. At the start of grade 8, she scored at the 53rd

percentile (see table two), a remarkable achievement for someone who had only

been in the US for two years. The ISAT is required from grades 2 to 10, but if

students achieve scores at the proficient level at grade 10, they need not take the

test again. Sophia reached this level.

Since 10

th

grade, Sophia has been a member of the National Honor Society. Last

year, she was selected as the outstanding junior year debater, even though it was

her first year participating in debate. At the time of this writing, Sophia is in

grade 12. She is enrolled, and is doing A work in, a college level English class,

and achieved a perfect score on the placement examination required for

enrollment.

Table 2: Sophias Percentile Rankings

acad yr %ile

gr 8:02-03 53>24

gr 9:03-04 75>54

gr 10: 04-05 68>47

Explaining the Mystery

Table three explains the mystery. It is a re-arrangement of Sophias scores to

reflect what happened over the summer; each summer, Sophia made substantial

gains in reading, making up for what she had lost during the academic year, and

then some:

Table 3: Sophias Summer Gains

summer %ile

8-9: (03) 24>75

9-10: (04) 54>68

What did Sophia do over the summer? Did she attend special classes, getting

instruction in reading strategies and meta-cognition? Did she work through

massive amounts of vocabulary lists? Did she read under a strict regimen,

applying grim determination to working through a list of required books,

completing book reports and summaries? The answer: None of the above. All she

did was read for pleasure: No book reports, no related reading activities and all

her reading was self-selected.

According to her mother, Sophia read an average of about 50 books per summer.

Early favorites were the Nancy Drew and Sweet Valley High series, and Sophia

then moved on the Christy Miller series and other books by Francine Pascal, the

author of the Sweet Valley series. (Sophia informed us that she was addicted to

the Christy Miller books; it took her only a week to read the entire series because

I just couldnt put them down.)

Her choices thus concur with research showing that series books are enormously

popular among young readers (Krashen and Ujiie 2005) and with arguments that

narrow reading is a very efficient way of building language competence,

because texts are interesting and comprehensible (Krashen 2004).

This is a startling result, but it is not new. Sophias experience is precisely what

was reported by Barbara Heyns in 1975, who showed that the difference in

reading development between children from low and middle incomes is because

of what happens over the summer: both groups make similar gains during the

year, but children from high income families improve over the summer, while

those from low-income families either stay the same or get worse. Over the years,

the difference builds up until it becomes very large (Entwhisle, Alexander, and

Olson 1997).

What Happens Over the Summer?

What happens over the summer that makes such a difference? Access to books

and reading. Heyns found that those who live closer to libraries read more, and

both Hayns and J. Kim (2005) found that children who read more over the

summer make more gains in reading.

Of course, Sophia had an advantage that not all children have: Access to plenty of

books.

The public library was the primary source for Sophias reading. The library had

summer reading program and Sophia joined it. After finishing reading a book, she

went back to check out another book. She got small prizes such as stickers as

rewards but the real reward was the pleasure Sophia received from reading her

self-selected books. (See Krashen, 2003, 2005 for a discussion of the lack of

research on rewards for reading, as well as possible dangers.) Sophia even took

the city bus with her younger brother to the public library when her mother was

too busy with work to take her to the library.

Sophia is also part of a family that supports education and encourages her to read.

Summer reading, encouraged by her mother, had been a regular part of Sophias

life for years. Sophia had been a pleasure reader in Mandarin before she and her

family moved to the United States, and lived in a print-rich environment in

Taiwan. After arriving in the US, however, she had no access to new books in

Mandarin, and had to learn to read in English to continue her pleasure reading

habit. She profited, thus, from de facto bilingual education, a good background

in her first language, and her case confirms that the pleasure reading habit

transfers across languages (Kim and Cho, 2005).

Sophias case is a good example of using resources from public libraries. The

summer reading program at the public library not only motivated Sophia to read,

but the wide variety of reading books also attracted her to visit again and again.

Not all children are so lucky, but the situation can be improved. More and better

public libraries are, of course, part of the solution, especially for children who

have no other sources of books.

Summer reading programs, those that emphasize lots of interesting reading and

gentle encouragement, have also been shown to be extremely effective. Shin

(2001) reported that her sixth graders grew a spectacular 1.3 years on the Nelson-

Denny reading comprehension test, from grade level 4.0 to grade 5.4, and equaled

comparisons (six months gain) in a traditional program in vocabulary growth

after only 5 and a half weeks in a program that included two hours of free reading

each day and regular trips to the school library.

The Effect of School Work on Reading

Rather than just work on improving book access during the summer, however, in

order to allow all children to improve as Sophia did, we must ask what happens

during the school year. It appears that much of what happens works against

reading development.

Sophias mother provides insight into the situation: During the school year,

Sophia is so busy with school work that she has hardly any free time to read.

Sophias mother, in fact, joked that it might be a good idea to keep her daughter at

home during the school year in order to increase her improvement on standardized

tests of reading.

Works Cited

Entwhistle, Doris, Alexander, Karl, and Olsen, Linda. 1997. Children, Schools, and

Inequality. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Heyns, Barbara. 1975. Summer Learning and the Effect of School. New York: Academic

Press.

Kim, Jimmy. 2003. Summer reading and the ethnic achievement gap, Journal of

Education for Students Placed at Risk 9, no. 2:169-188.

Kim, Hae Young and Cho, Kyung Sook. 2005. The influence of first language reading

on second language reading and second language acquisition, International

Journal of Foreign Language Teaching 1, no. 4: 13-16.

Krashen, Stephen. 1996. Under Attack: The Case Against Bilingual Education. Culver

City: Language Education Associates.

Krashen, Stephen. 2003. The (lack of) experimental evidence supporting the use of

accelerated reader, Journal of Childrens Literature 29, no.2: 9, 16-30.

Krashen, Stephen. 2005. Accelerated reader: Evidence still lacking, Knowledge Quest

33 no. 3: 48-49.

Krashen, Stephen, and Ujiie, Joanne. 2005. Junk food is bad for you, but junk reading is

good for you, International Journal of Foreign Language Teaching 1 no.3: 5-12.

Shin, Fay. 2001. Motivating students with Goosebumps and other popular books, CSLA

Journal (California School Library Association) 25 no. 1: 15-19.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Narrative Reports: Elise's Learner Narrative: "I Like Reading, But I Don't Like Chatter."Documento7 pagineNarrative Reports: Elise's Learner Narrative: "I Like Reading, But I Don't Like Chatter."kaedelarosaNessuna valutazione finora

- Inquiry Project For SchoolingDocumento7 pagineInquiry Project For Schoolingapi-264834813Nessuna valutazione finora

- Focal Student PortfolioDocumento38 pagineFocal Student Portfolioapi-293432552Nessuna valutazione finora

- Unit PlanDocumento103 pagineUnit PlanBlair Bucci100% (1)

- The High-Performing Preschool: Story Acting in Head Start ClassroomsDa EverandThe High-Performing Preschool: Story Acting in Head Start ClassroomsNessuna valutazione finora

- Hardy Case Study FinalDocumento28 pagineHardy Case Study Finalapi-279556324Nessuna valutazione finora

- Late Intervention: Free Voluntary ReadingDocumento8 pagineLate Intervention: Free Voluntary ReadingNhâtTânNessuna valutazione finora

- Favorite Read AloudDocumento4 pagineFavorite Read Aloudapi-510685621Nessuna valutazione finora

- MasterbibDocumento6 pagineMasterbibapi-295540257Nessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study - Raim 12Documento36 pagineCase Study - Raim 12api-452790416Nessuna valutazione finora

- Booklist ProjectDocumento10 pagineBooklist Projectapi-559973826Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cszi Yn ZLDocumento416 pagineCszi Yn ZLBudi SantosoNessuna valutazione finora

- ct820 Interviewproject SalinasDocumento14 paginect820 Interviewproject Salinasapi-303163662Nessuna valutazione finora

- Project 2: "Needs Analysis" Fieldwork and ReportDocumento4 pagineProject 2: "Needs Analysis" Fieldwork and Reportapi-531717294Nessuna valutazione finora

- Responding To Student Needs - Literacy BiographyDocumento4 pagineResponding To Student Needs - Literacy Biographyapi-255938035Nessuna valutazione finora

- Red 4312 Case StudyDocumento30 pagineRed 4312 Case Studyapi-300485205Nessuna valutazione finora

- 1 Running Head: PEPSI SCREENINGDocumento11 pagine1 Running Head: PEPSI SCREENINGapi-296983580Nessuna valutazione finora

- Research PaperDocumento10 pagineResearch Paperapi-301896424Nessuna valutazione finora

- Class and Campus Life: Managing and Experiencing Inequality at an Elite CollegeDa EverandClass and Campus Life: Managing and Experiencing Inequality at an Elite CollegeNessuna valutazione finora

- Simmons Case Study Eed225Documento7 pagineSimmons Case Study Eed225api-280357644Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ya Lit Research PaperDocumento12 pagineYa Lit Research Paperapi-557418832Nessuna valutazione finora

- Narrow Free Reading Boosts ESL ProgressDocumento5 pagineNarrow Free Reading Boosts ESL Progressagostina larrouletNessuna valutazione finora

- Teacher InterviewDocumento5 pagineTeacher Interviewapi-533618032Nessuna valutazione finora

- Silence in The Classroom: Learning To Talk About Issues of RaceDocumento17 pagineSilence in The Classroom: Learning To Talk About Issues of RaceMogonea Florentin RemusNessuna valutazione finora

- 1994 Sweet Valley High With KschoDocumento7 pagine1994 Sweet Valley High With KschoIrisha AnandNessuna valutazione finora

- Elementary School Library Media Specialist Interview #1Documento5 pagineElementary School Library Media Specialist Interview #1Tam NaturalsNessuna valutazione finora

- Yale_-_Sample_Interview_ReportsDocumento6 pagineYale_-_Sample_Interview_ReportsandresianpiNessuna valutazione finora

- White Teacher: With a New Preface, Third EditionDa EverandWhite Teacher: With a New Preface, Third EditionValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (19)

- Case Study On Ostracism in Schoolchildren - K. GreerDocumento1 paginaCase Study On Ostracism in Schoolchildren - K. GreerVivienne92Nessuna valutazione finora

- Jcel PaperDocumento12 pagineJcel Paperapi-378481314Nessuna valutazione finora

- You AreDocumento8 pagineYou Areapi-534309724Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ela PaperDocumento7 pagineEla Paperapi-626846282Nessuna valutazione finora

- What Is John Dewey Doing in To Kill A MockingbirdDocumento16 pagineWhat Is John Dewey Doing in To Kill A MockingbirdWa DsNessuna valutazione finora

- Eip 2Documento10 pagineEip 2api-251878619Nessuna valutazione finora

- Apprtrackformslc 1Documento2 pagineApprtrackformslc 1api-345766446Nessuna valutazione finora

- Edu 342 - Read-Aloud 2 LPDocumento3 pagineEdu 342 - Read-Aloud 2 LPapi-532832020Nessuna valutazione finora

- Child Study LFDocumento7 pagineChild Study LFapi-317138568Nessuna valutazione finora

- OutlineDocumento3 pagineOutlineapi-245863015Nessuna valutazione finora

- Silence in The Classroom - Learning To Talk About Issues of RaceDocumento9 pagineSilence in The Classroom - Learning To Talk About Issues of RaceVisnja FlegarNessuna valutazione finora

- General School InformationDocumento25 pagineGeneral School Informationapi-435756364Nessuna valutazione finora

- Literacy Narrative Draft and Peer ReviewDocumento6 pagineLiteracy Narrative Draft and Peer Reviewapi-270988963Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Victims of Dick and JaneDocumento19 pagineThe Victims of Dick and JaneHal ShurtleffNessuna valutazione finora

- A Fourth-Grader's Perspective on a Student-Centered Learning EnvironmentDocumento5 pagineA Fourth-Grader's Perspective on a Student-Centered Learning EnvironmentJuan David Beltrán GaitánNessuna valutazione finora

- Study Child Project Study Child Project: Priscila FojanDocumento24 pagineStudy Child Project Study Child Project: Priscila FojanfojanpriNessuna valutazione finora

- Tws 1Documento12 pagineTws 1api-236766479Nessuna valutazione finora

- Edu 5010 - CHDocumento8 pagineEdu 5010 - CHapi-458039569Nessuna valutazione finora

- Teaching Cross-Culturally: An Incarnational Model for Learning and TeachingDa EverandTeaching Cross-Culturally: An Incarnational Model for Learning and TeachingValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5)

- AssignmentDocumento18 pagineAssignmentapi-297973312Nessuna valutazione finora

- Eng 496 Senior ThesisDocumento15 pagineEng 496 Senior Thesisapi-508326675Nessuna valutazione finora

- Language Acquisition AutobiographyDocumento6 pagineLanguage Acquisition Autobiographyapi-712106452Nessuna valutazione finora

- Hollins Linguistic Introspective PieceDocumento7 pagineHollins Linguistic Introspective Pieceapi-535560726Nessuna valutazione finora

- University Copy Transition ProjectDocumento27 pagineUniversity Copy Transition Projectapi-312581689Nessuna valutazione finora

- Action Report Research PaperDocumento6 pagineAction Report Research Paperapi-710156794Nessuna valutazione finora

- Multicultural Text SetDocumento21 pagineMulticultural Text Setapi-313116584Nessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study 3-Final ReportDocumento22 pagineCase Study 3-Final Reportapi-315049671Nessuna valutazione finora

- Inquiry ProjectDocumento14 pagineInquiry Projectapi-356637264Nessuna valutazione finora

- Motivation For Content ReadersDocumento29 pagineMotivation For Content Readersjena21885100% (1)

- Studies. Literature2Documento5 pagineStudies. Literature2Fabian Regine G.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Hilliard Preface FinalDocumento8 pagineHilliard Preface Finalapi-242602625Nessuna valutazione finora

- Educational Researcher 1992 Lee 33 4Documento2 pagineEducational Researcher 1992 Lee 33 4Aminatul Rasyidah GhazaliNessuna valutazione finora

- Foreign-Language 1125 PDFDocumento56 pagineForeign-Language 1125 PDFFernando Carvajal CaceresNessuna valutazione finora

- Foreign-Language 1125 PDFDocumento56 pagineForeign-Language 1125 PDFFernando Carvajal CaceresNessuna valutazione finora

- Pickit 3 LPC Demo Board SCHDocumento1 paginaPickit 3 LPC Demo Board SCHNhâtTânNessuna valutazione finora

- Code Lập Trình Hợp Ngữ Căn BảnDocumento38 pagineCode Lập Trình Hợp Ngữ Căn BảnNhâtTânNessuna valutazione finora

- Why Invest in LibrariesDocumento9 pagineWhy Invest in LibrariesNhâtTânNessuna valutazione finora

- Late Intervention: Free Voluntary ReadingDocumento8 pagineLate Intervention: Free Voluntary ReadingNhâtTânNessuna valutazione finora

- Reading and Vocab A CQDocumento17 pagineReading and Vocab A CQKaren Olave EncinaNessuna valutazione finora

- t'i+1'│す │'十 1'│+!′ !+!′ 十li■'i十 1'1+i,i十 1′ !+1': 'i十 !′ │■ 1,■:'i+i,■:,!+!rlす │,!+十 !+i,i+!'十 1Documento2 paginet'i+1'│す │'十 1'│+!′ !+!′ 十li■'i十 1'1+i,i十 1′ !+1': 'i十 !′ │■ 1,■:'i+i,■:,!+!rlす │,!+十 !+i,i+!'十 1NhâtTânNessuna valutazione finora

- Invitation Letter: To: Mr. Huỳnh Triệu Nhật Tân, Hardware Design EngineerDocumento3 pagineInvitation Letter: To: Mr. Huỳnh Triệu Nhật Tân, Hardware Design EngineerNhâtTânNessuna valutazione finora

- Many HypothesisDocumento16 pagineMany HypothesisNhâtTânNessuna valutazione finora

- Defending Whole LanguageDocumento13 pagineDefending Whole LanguageNhâtTânNessuna valutazione finora

- Basic PhonicsDocumento4 pagineBasic PhonicsNhâtTânNessuna valutazione finora

- DeThi HeThongThongTinHangKhongDocumento2 pagineDeThi HeThongThongTinHangKhongNhâtTânNessuna valutazione finora

- Are Prize-Winning Books PopularDocumento3 pagineAre Prize-Winning Books PopularNhâtTânNessuna valutazione finora

- The Pot Calls The Kettle BlackDocumento2 pagineThe Pot Calls The Kettle Blackvinoelnino10Nessuna valutazione finora

- Pure Pa and RCDocumento2 paginePure Pa and RCNhâtTânNessuna valutazione finora

- Decoding & ComprehensionDocumento6 pagineDecoding & ComprehensionNhâtTânNessuna valutazione finora

- Phonemic Awareness TrainingDocumento5 paginePhonemic Awareness Trainingde061185Nessuna valutazione finora

- Krashen Hastings Phonemicawareness Ijflt 11-11Documento5 pagineKrashen Hastings Phonemicawareness Ijflt 11-11NhâtTânNessuna valutazione finora

- DeThi HeThongThongTinHangKhongDocumento2 pagineDeThi HeThongThongTinHangKhongNhâtTânNessuna valutazione finora

- Start EarlyDocumento8 pagineStart EarlyNhâtTânNessuna valutazione finora

- Great PlummetDocumento6 pagineGreat PlummetNhâtTânNessuna valutazione finora

- Matlab CodeDocumento6 pagineMatlab CodeNhâtTânNessuna valutazione finora

- 88 GeneralizationsDocumento4 pagine88 GeneralizationsNhâtTânNessuna valutazione finora

- Design of Greenhouse Control System Based On Wireless Sensor Networks and AVR MicrocontrollerDocumento7 pagineDesign of Greenhouse Control System Based On Wireless Sensor Networks and AVR MicrocontrollerNhâtTânNessuna valutazione finora

- P 1685 Metal Detecting RobotDocumento42 pagineP 1685 Metal Detecting RobotSairam Varma MNessuna valutazione finora

- Reading and Vocab A CQDocumento17 pagineReading and Vocab A CQKaren Olave EncinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Line Follower ATMEGA16 WWW - Robotechno.usDocumento17 pagineLine Follower ATMEGA16 WWW - Robotechno.usSarang WadekarNessuna valutazione finora

- R Rec SM.1009 1 199510 I!!pdf eDocumento41 pagineR Rec SM.1009 1 199510 I!!pdf eNhâtTânNessuna valutazione finora

- Evolving Useful ObjectsDocumento4 pagineEvolving Useful ObjectsDavid Orban100% (3)

- Grade 6 Values EdDocumento2 pagineGrade 6 Values EdGERARD VILLAFLORESNessuna valutazione finora

- Michael Lukie - IHPST Conference Poster 2013Documento1 paginaMichael Lukie - IHPST Conference Poster 2013mplukieNessuna valutazione finora

- UNIT 16 Data Presentation: CSEC Multiple Choice QuestionsDocumento3 pagineUNIT 16 Data Presentation: CSEC Multiple Choice Questionsglenn0% (1)

- Assignment Cover Page - PathophysiologyDocumento6 pagineAssignment Cover Page - PathophysiologyAnonymous HcjWDGDnNessuna valutazione finora

- 4 Foundations To Help Trauma-Impacted YouthDocumento4 pagine4 Foundations To Help Trauma-Impacted YouthwaleskacrzNessuna valutazione finora

- Learn LenormandDocumento3 pagineLearn LenormandDianaCastle100% (2)

- Mentality by AshiaryDocumento11 pagineMentality by AshiaryRaito 0o0Nessuna valutazione finora

- Fire Engineer ResumeDocumento4 pagineFire Engineer ResumeBenjaminNessuna valutazione finora

- Thesis VDocumento43 pagineThesis Vparis escritor100% (2)

- Philippians 4 13 - PPT DEFENSEDocumento17 paginePhilippians 4 13 - PPT DEFENSESherwina Marie del RosarioNessuna valutazione finora

- Initial Data Base For Family Nursing PracticeDocumento12 pagineInitial Data Base For Family Nursing Practicemiss RN67% (18)

- English 7 Q2 M6Documento20 pagineEnglish 7 Q2 M6Jervin BolisayNessuna valutazione finora

- BAFI507 M&A Course OverviewDocumento10 pagineBAFI507 M&A Course Overviewuygh g100% (1)

- Understanding Your Response to Adversity with the Adversity Response ProfileDocumento9 pagineUnderstanding Your Response to Adversity with the Adversity Response ProfileRaihanah ZahraNessuna valutazione finora

- RPH Week 14 2019Documento18 pagineRPH Week 14 2019Faizah FaizNessuna valutazione finora

- Family Therapy Working With Challenging Family Dynamics in Effective MannerDocumento76 pagineFamily Therapy Working With Challenging Family Dynamics in Effective MannerManishaNessuna valutazione finora

- Factor Affecting Rural MarketingDocumento5 pagineFactor Affecting Rural Marketingshaileshkumargupta100% (1)

- The Filipino Value System and Its Effects On BusinessDocumento4 pagineThe Filipino Value System and Its Effects On BusinessQueleNessuna valutazione finora

- Red Cosmic DragonDocumento6 pagineRed Cosmic DragonSugihGandanaNessuna valutazione finora

- GUIDELINES FOR REPORT WRITINGDocumento8 pagineGUIDELINES FOR REPORT WRITINGShumaila MirzaNessuna valutazione finora

- Managing Business Through Human Psychology A Handbook For EntrepreneurDocumento253 pagineManaging Business Through Human Psychology A Handbook For EntrepreneurCorina CrazylilkidNessuna valutazione finora

- King Lear NotesDocumento5 pagineKing Lear NotesirregularflowersNessuna valutazione finora

- Challenges Faced by H R Managers in The Contemporary Business AtmosphereDocumento3 pagineChallenges Faced by H R Managers in The Contemporary Business AtmospheresogatNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit Plan BadmintonDocumento4 pagineUnit Plan Badmintonapi-215259691Nessuna valutazione finora

- Portfolio SociolinguisticsDocumento7 paginePortfolio SociolinguisticsAndreea-Raluca ManeaNessuna valutazione finora

- Leadership Management ProjectDocumento185 pagineLeadership Management ProjectSumit Chowdhury0% (1)

- Curriculum-Map-TLE-8 HANDICRAFT MAKING-NAIL CARE SERVICESDocumento16 pagineCurriculum-Map-TLE-8 HANDICRAFT MAKING-NAIL CARE SERVICESAndreyjoseph BayangNessuna valutazione finora

- Sample Registered Nurse (RN) ResumeDocumento2 pagineSample Registered Nurse (RN) ResumeBlogging SmartNessuna valutazione finora