Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Premiere Development Bank vs. Flores GR 175339

Caricato da

Keith BalbinCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Premiere Development Bank vs. Flores GR 175339

Caricato da

Keith BalbinCopyright:

Formati disponibili

9/21/2014 G.R. No.

175339

http://www.lawphil.net/judjuris/juri2008/dec2008/gr_175339_2008.html 1/6

Today is Sunday, September 21, 2014

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

SECOND DIVISION

G.R. No. 175339 December 16, 2008

PREMIERE DEVELOPMENT BANK, petitioner,

vs.

ALFREDO C. FLORES, in his Capacity as Presiding Judge of Regional Trial Court of Pasig City, Branch 167,

ARIZONA TRANSPORT CORPORATION and PANACOR MARKETING CORPORATION, respondents.

D E C I S I O N

TINGA, J.:

This is a Rule 45 petition for review

1

of the Court of Appeals decision

2

in CA-G.R. SP No. 92908 which affirmed the

Regional Trial Courts (RTCs) orders

3

granting respondent corporations motion for execution of the Courts 14 April

2004 decision in G.R. No. 159352

4

and denying

5

petitioner Premiere Development Banks motion for

reconsideration, as well as the appellate courts resolution

6

denying Premiere Development Banks motion for

reconsideration.

The factual antecedents of the case, as found by the Court in G.R. No. 159352, are as follows:

The undisputed facts show that on or about October 1994, Panacor Marketing Corporation (Panacor for

brevity), a newly-formed corporation, acquired an exclusive distributorship of products manufactured by

Colgate Palmolive Philippines, Inc. (Colgate for short). To meet the capital requirements of the exclusive

distributorship, which required an initial inventory level of P7.5 million, Panacor applied for a loan of P4.1

million with Premiere Development Bank. After an extensive study of Panacors creditworthiness, Premiere

Bank rejected the loan application and suggested that its affiliate company, Arizona Transport Corporation

(Arizona for short), should instead apply for the loan on condition that the proceeds thereof shall be made

available to Panacor. Eventually, Panacor was granted a P4.1 million credit line as evidenced by a Credit Line

Agreement. As suggested, Arizona, which was an existing loan client, applied for and was granted a loan of

P6.1 million, P3.4 million of which would be used to pay-off its existing loan accounts and the remaining P2.7

million as credit line of Panacor. As security for the P6.1 million loan, Arizona, represented by its Chief

Executive Officer Pedro Panaligan and spouses Pedro and Marietta Panaligan in their personal capacities,

executed a Real Estate Mortgage against a parcel of land covered by TCT No. T-3475 as per Entry No.

49507 dated October 2, 1995.

Since the P2.7 million released by Premiere Bank fell short of the P4.1 million credit line which was previously

approved, Panacor negotiated for a take-out loan with IBA-Finance Corporation (hereinafter referred to as

IBA-Finance) in the sum of P10 million, P7.5 million of which will be released outright in order to take-out the

loan from Premiere Bank and the balance of P2.5 million (to complete the needed capital of P4.1 million with

Colgate) to be released after the cancellation by Premiere of the collateral mortgage on the property covered

by TCT No. T-3475. Pursuant to the said take-out agreement, IBA-Finance was authorized to pay Premiere

Bank the prior existing loan obligations of Arizona in an amount not to exceed P6 million.

On October 5, 1995, Iba-Finance sent a letter to Ms. Arlene R. Martillano, officer-in-charge of Premiere

Banks San Juan Branch, informing her of the approved loan in favor of Panacor and Arizona, and requesting

for the release of TCT No. T-3475. Martillano, after reading the letter, affixed her signature of conformity

thereto and sent the original copy to Premiere Banks legal office. x x x

On October 12, 1995, Premiere Bank sent a letter-reply to [IBA]-Finance, informing the latter of its refusal to

turn over the requested documents on the ground that Arizona had existing unpaid loan obligations and that it

was the banks policy to require full payment of all outstanding loan obligations prior to the release of

mortgage documents. Thereafter, Premiere Bank issued to IBA-Finance a Final Statement of Account

showing Arizonas total loan indebtedness. On October 19, 1995, Panacor and Arizona executed in favor of

IBA-Finance a promissory note in the amount of P7.5 million. Thereafter, IBA-Finance paid to Premiere Bank

the amount of P6,235,754.79, representing the full outstanding loan account of Arizona. Despite such

payment, Premiere Bank still refused to release the requested mortgage documents specifically, the owners

duplicate copy of TCT No. T-3475.

On November 2, 1995, Panacor requested IBA-Finance for the immediate approval and release of the

remaining P2.5 million loan to meet the required monthly purchases from Colgate. IBA-Finance explained

9/21/2014 G.R. No. 175339

http://www.lawphil.net/judjuris/juri2008/dec2008/gr_175339_2008.html 2/6

however, that the processing of the P2.5 million loan application was conditioned, among others, on the

submission of the owners duplicate copy of TCT No. 3475 and the cancellation by Premiere Bank of

Arizonas mortgage. Occasioned by Premiere Banks adamant refusal to release the mortgage cancellation

document, Panacor failed to generate the required capital to meet its distribution and sales targets. On

December 7, 1995, Colgate informed Panacor of its decision to terminate their distribution agreement.

On March 13, 1996, Panacor and Arizona filed a complaint for specific performance and damages against

Premiere Bank before the Regional Trial Court of Pasig City, docketed as Civil Case No. 65577.

On June 11, 1996, IBA-Finance filed a complaint-in-intervention praying that judgment be rendered ordering

Premiere Bank to pay damages in its favor.

On May 26, 1998, the trial court rendered a decision in favor of Panacor and IBA-Finance, the decretal

portion of which reads: x x x

Premiere Bank appealed to the Court of Appeals contending that the trial court erred in finding, inter alia, that

it had maliciously downgraded the credit-line of Panacor from P4.1 million to P2.7 million.

In the meantime, a compromise agreement was entered into between IBA-Finance and Premiere Bank

whereby the latter agreed to return without interest the amount of P6,235,754.79 which IBA-Finance earlier

remitted to Premiere Bank to pay off the unpaid loans of Arizona. On March 11, 1999, the compromise

agreement was approved.

On June 18, 2003, a decision was rendered by the Court of Appeals which affirmed with modification the

decision of the trial court, the dispositive portion of which reads:

7

x x x

Incidentally, respondent corporations received a notice of sheriffs sale during the pendency of G.R. No. 159352.

Respondent corporations were able to secure an injunction from the RTC but it was set aside by the Court of

Appeals in a decision dated 20 August 2004.

8

The appellate court denied respondent corporations motion for

reconsideration in a resolution dated 5 November 2004.

9

The Court, in a resolution dated 16 February 2005, did not give due course to the petition for review of respondent

corporations as it did not find any reversible error in the decision of the appellate court.

10

After the Court had denied

with finality the motion for reconsideration,

11

the mortgaged property was purchased by Premiere Development

Bank at the foreclosure sale held on 19 September 2005 for P6,600,000.00.

12

Respondent corporations filed a motion for execution dated 25 August 2005

13

asking for the issuance of a writ of

execution of our decision in G.R. No. 159352 where we awarded P800,000.00 as damages in their favor.

14

The

RTC granted the writ of execution sought. The Court of Appeals affirmed the order.

Hence, the present petition for review.

The only question before us is the propriety of the grant of the writ of execution by the RTC.

Premiere Development Bank argues that the lower courts should have applied the principles of compensation or

set-off as the foreclosure of the mortgaged property does not preclude it from filing an action to recover any

deficiency from respondent corporations loan. It allegedly did not file an action to recover the loan deficiency from

respondent corporations because of the pending Civil Case No. MC03-2202 filed by respondent corporations before

the RTC of Mandaluyong City entitled Arizona Transport Corp. v. Premiere Development Bank. That case puts into

issue the validity of Premiere Development Banks monetary claim against respondent corporations and the

subsequent foreclosure sale of the mortgaged property. Premiere Development Bank allegedly had wanted to wait

for the resolution of the civil case before it would file its deficiency claims against respondent corporations.

Moreover, the execution of our decision in G.R. No. 159352 would allegedly be iniquitous and unfair since

respondent corporations are already in the process of winding up.

15

The Court finds the petition unmeritorious.

A judgment becomes "final and executory" by operation of law. In such a situation, the prevailing party is entitled to

a writ of execution, and issuance thereof is a ministerial duty of the court.

16

This policy is clearly and emphatically

embodied in Rule 39, Section 1 of the Rules of Court, to wit:

SECTION 1. Execution upon judgments or final orders. Execution shall issue as a matter of right, on motion,

upon a judgment or order that disposes of the action or proceeding upon the expiration of the period to appeal therefrom

if no appeal has been duly perfected.

If the appeal has been duly perfected and finally resolved, the execution may forthwith be applied for in the

court of origin, on motion of the judgment obligee, submitting therewith certified true copies of the judgment or

judgments or final order or orders sought to be enforced and of the entry thereof, with notice to the adverse

party.

The appellate court may, on motion in the same case, when the interest of justice so requires, direct the court

of origin to issue the writ of execution. (Emphasis supplied.)

9/21/2014 G.R. No. 175339

http://www.lawphil.net/judjuris/juri2008/dec2008/gr_175339_2008.html 3/6

Jurisprudentially, the Court has recognized certain exceptions to the rule as where in cases of special and

exceptional nature it becomes imperative in the higher interest of justice to direct the suspension of its execution;

whenever it is necessary to accomplish the aims of justice; or when certain facts and circumstances transpired after

the judgment became final which could render the execution of the judgment unjust.

17

None of these exceptions avails to stay the execution of this Courts decision in G.R. No. 159352. Premiere

Development Bank has failed to show how injustice would exist in executing the judgment other than the allegation

that respondent corporations are in the process of winding up. Indeed, no new circumstance transpired after our

judgment had become final that would render the execution unjust.

The Court cannot give due course to Premiere Development Banks claim of compensation or set-off on account of

the pending Civil Case No. MC03-2202 before the RTC of Mandaluyong City. For compensation to apply, among

other requisites, the two debts must be liquidated and demandable already.

18

A distinction must be made between a debt and a mere claim. A debt is an amount actually ascertained. It is a claim

which has been formally passed upon by the courts or quasi-judicial bodies to which it can in law be submitted and

has been declared to be a debt. A claim, on the other hand, is a debt in embryo. It is mere evidence of a debt and

must pass thru the process prescribed by law before it develops into what is properly called a debt.

19

Absent,

however, any such categorical admission by an obligor or final adjudication, no legal compensation or off-set can

take place. Unless admitted by a debtor himself, the conclusion that he is in truth indebted to another cannot be

definitely and finally pronounced, no matter how convinced he may be from the examination of the pertinent records

of the validity of that conclusion the indebtedness must be one that is admitted by the alleged debtor or pronounced

by final judgment of a competent court.

20

At best, what Premiere Development Bank has against respondent

corporations is just a claim, not a debt. At worst, it is a speculative claim.

The alleged deficiency claims of Premiere Development Bank should have been raised as a compulsory

counterclaim before the RTC of Mandaluyong City where Civil Case No. MC03-2202 is pending. Under Section 7,

Rule 6 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure, a counterclaim is compulsory when its object "arises out of or is

necessarily connected with the transaction or occurrence constituting the subject matter of the opposing partys

claim and does not require for its adjudication the presence of third parties of whom the court cannot acquire

jurisdiction". In Quintanilla v. CA

21

and reiterated in Alday v. FGU Insurance Corporation,

22

the "compelling test of

compulsoriness" characterizes a counterclaim as compulsory if there should exist a "logical relationship" between

the main claim and the counterclaim. There exists such a relationship when conducting separate trials of the

respective claims of the parties would entail substantial duplication of time and effort by the parties and the court;

when the multiple claims involve the same factual and legal issues; or when the claims are offshoots of the same

basic controversy between the parties. Clearly, the recovery of Premiere Development Banks alleged deficiency

claims is contingent upon the case filed by respondent corporations; thus, conducting separate trials thereon will

result in a substantial duplication of the time and effort of the court and the parties.

The fear of Premiere Development Bank that they would have difficulty collecting its alleged loan deficiencies from

respondent corporations since they were already involuntarily dissolved due to their failure to file reportorial

requirements with the Securities and Exchange Commission is neither here nor there. In any event, the law

specifically allows a trustee to manage the affairs of the corporation in liquidation, and the dissolution of the

corporation would not serve as an effective bar to the enforcement of rights for or against it.

As early as 1939,

23

this Court held that, although the time during which the corporation, through its own officers,

may conduct the liquidation of its assets and sue and be sued as a corporation is limited to three years from the time

the period of dissolution commences, there is no time limit within which the trustees must complete a liquidation

placed in their hands. What is provided in Section 122

24

of the Corporation Code is that the conveyance to the

trustees must be made within the three-year period. But it may be found impossible to complete the work of

liquidation within the three-year period or to reduce disputed claims to judgment. The trustees to whom the

corporate assets have been conveyed pursuant to the authority of Section 122 may sue and be sued as such in all

matters connected with the liquidation.

Furthermore, Section 145 of the Corporation Code clearly provides that "no right or remedy in favor of or against

any corporation, its stockholders, members, directors, trustees, or officers, nor any liability incurred by any such

corporation, stockholders, members, directors, trustees, or officers, shall be removed or impaired either by the

subsequent dissolution of said corporation." Even if no trustee is appointed or designated during the three-year

period of the liquidation of the corporation, the Court has held that the board of directors may be permitted to

complete the corporate liquidation by continuing as "trustees" by legal implication.

25

Therefore, no injustice would

arise even if the Court does not stay the execution of G.R. 159352.

Although it is commendable for Premiere Development Bank in offering to deposit with the RTC the P800,000.00 as

an alternative prayer, the Court cannot allow it to defeat or subvert the right of respondent corporations to have the

final and executory decision in G.R. No. 159352 executed. The offer to deposit cannot suspend the execution of this

Courts decision for this cannot be deemed as consignation. Consignation is the act of depositing the thing due with

the court or judicial authorities whenever the creditor cannot accept or refuses to accept payment, and it generally

requires a prior tender of payment. In this case, it is Premiere Development Bank, the judgment debtor, who refused

to pay respondent corporations P800,000.00 and not the other way around. Neither could such offer to make a

deposit with the RTC provide a ground for this Court to issue an injunctive relief in this case.

WHEREFORE, the petition for review is DENIED. The decision of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. SP No. 92908 is

9/21/2014 G.R. No. 175339

http://www.lawphil.net/judjuris/juri2008/dec2008/gr_175339_2008.html 4/6

AFFIRMED.

SO ORDERED.

DANTE O. TINGA

Associate Justice

WE CONCUR:

LEONARDO A. QUISUMBING

Associate Justice

Chairperson

CONCHITA CARPIO MORALES

Associate Justice

PRESBITERO J. VELASCO, JR.

Associate Justice

ARTURO D. BRION

Associate Justice

ATTESTATION

I attest that the conclusions in the above Decision had been reached in consultation before the case was assigned

to the writer of the opinion of the Courts Division.

LEONARDO A. QUISUMBING

Associate Justice

Chairperson, Second Division

CERTIFICATION

Pursuant to Section 13, Article VIII of the Constitution, and the Division Chairpersons Attestation, it is hereby

certified that the conclusions in the above Decision were reached in consultation before the case was assigned to

the writer of the opinion of the Courts Division.

REYNATO S. PUNO

Chief Justice

Footnotes

1

Rollo, pp. 3-40.

2

Id. at 45-61. Penned by Associate Justice Mariano Del Castillo; concurred in by Associate Justices Conrado

Vasquez, Jr. and Vicente Veloso. The dispositive portion of the decision reads as follows:

WHEREFORE, the instant petition is DISMISSED. Accordingly, the assailed orders are AFFIRMED.

SO ORDERED.

3

Id. at 109-110. Penned by Judge Alfredo Flores. The dispositive portion reads as follows:

WHEREFORE, premises considered, let a writ of execution issue for the enforcement of the Decision

of this (C)ourt on 18 June 2003, as affirmed but modified by the Supreme Court in G.R. No. 159352

under the Decision rendered on 14 April 2004, on the payment of the following, namely: Php

500,000.00 as exemplary damages; Php 100,000.00 as attorneys fees; and Php 200,000.00, as

temperate damages, to be accordingly implemented by the Deputy Sheriff of this Court.

SO ORDERED.

4

Premiere Development Bank v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 159352, 14 April 2004, 427 SCRA 686.

5

Rollo, p. 111.

6

Id. at 63.

7

Premiere Development Bank v. Court of Appeals, supra note 4 at 689-693.

9/21/2014 G.R. No. 175339

http://www.lawphil.net/judjuris/juri2008/dec2008/gr_175339_2008.html 5/6

8

Rollo, pp. 127-132.

9

Id. at 145-146.

10

Id. at 147.

11

Id. at 148.

12

Id. at 151-152.

13

CA rollo, pp. 113-117.

14

Premiere Development Bank v. Court of Appeals, supra note 4 at 700. The dispositive portion of the

Courts decision reads as follows:

WHEREFORE, the petition is DENIED. The Decision dated June 18, 2003 of the Court of Appeals in

CA-G.R. CV No. 60750, ordering Premiere Bank to pay Panacor Marketing Corporation P500,000.00

as exemplary damages, P100,000.00 as attorneys fees, and costs, is AFFIRMED, with the

MODIFICATION that the award of P4,520,000.00 as actual damages is DELETED for lack of factual

basis. In lieu thereof, Premiere Bank is ordered to pay Panacor P200,000.00 as temperate damages.

SO ORDERED.

15

Rollo, pp. 134-135.

16

City of Manila v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 100626, 29 November 1991, 204 SCRA 362, 366.

17

Cruz v. Leabres, 314 Phil. 26, 34 (1995), citing Lipana v. Development Bank of Rizal, 154 SCRA 257

(1987).

18

Art. 1278. Compensation shall take place when two persons, in their own right, are creditors and debtors of

each other. (1159)

Art. 1279. In order that compensation may be proper, it is necessary:

(1) That each one of the obligors be bound principally, and that he be at the same time a principal

creditor of the other;

(2) That both debts consist in a sum of money, or if the things due are consumable, they be of the

same kind, and also of the same quality if the latter has been stated;

(3) That the two debts be due;

(4) That they be liquidated and demandable;

(5) That over neither of them there be any retention or controversy, commenced by third persons and

communicated in due time to the debtor.

19

Vallarta v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. L-36543, 27 July 1988, 163 SCRA 587, 594.

20

See Villanueva v. Tantuico, Jr., G.R. No. 53585, 15 February 1990, 182 SCRA 263, 267-268.

21

344 Phil. 811 (1997).

22

402 Phil. 962 (2001).

23

Sumera v. Valencia, 67 Phil. 721, 726 (1939).

24

SEc. 122. Corporate Liquidation. Every corporation whose charter expires by its own limitation or is

annulled by forfeiture or otherwise, or whose corporate existence for other purposes is terminated in any

other manner, shall nevertheless be continued as a body corporate for three (3) years after the time when it

would have been so dissolved, for the purpose of prosecuting and defending suits by or against it and

enabling it to settle and close its affairs, to dispose of and convey its property and to distribute its assets, but

not for the purpose of continuing the business for which it was established.

At any time during said three (3) years, said corporation is authorized and empowered to convey all of its

property to trustees for the benefit of stockholders, members, creditors, and other persons in interest. From

and after any such conveyance by the corporation of its property in trust for the benefit of its stockholders,

members, creditors and others in interests, all interest which the corporation had in the property terminates,

the legal interest vests in the trustees, and the beneficial interest in the stockholders, members, creditors or

other persons in interest.

9/21/2014 G.R. No. 175339

http://www.lawphil.net/judjuris/juri2008/dec2008/gr_175339_2008.html 6/6

Upon winding up of the corporate affairs, any asset distributable to any creditor or stockholder or member

who is unknown or cannot be found shall be escheated to the city or municipality where such assets are

located.

Except by decrease of capital stock and as otherwise allowed by this Code, no corporation shall distribute any

of its assets or property except upon lawful dissolution and after payment of all its debts and liabilities.

25

Reburiano v. Court of Appeals, 361 Phil. 294, 307 (1999) citing Clemente v. Court of Appeals, 242 SCRA

717 (1995).

The Lawphil Project - Arellano Law Foundation

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- 10 Genil Vs RiveraDocumento9 pagine10 Genil Vs RiveraLimberge Paul CorpuzNessuna valutazione finora

- Puente - Arizona - Et - Al - v. - Arpai Defendants' Amended Joint Controverting Statement of FactsDocumento64 paginePuente - Arizona - Et - Al - v. - Arpai Defendants' Amended Joint Controverting Statement of FactsChelle CalderonNessuna valutazione finora

- (Mercantile Law) Bar AnswersDocumento17 pagine(Mercantile Law) Bar AnswersJoseph Tangga-an GiduquioNessuna valutazione finora

- Complaint Against Strulovich and OberlanderDocumento32 pagineComplaint Against Strulovich and OberlanderDNAinfoNewYorkNessuna valutazione finora

- Tenants' Class-Action Lawsuit Against The Columbia Housing AuthorityDocumento16 pagineTenants' Class-Action Lawsuit Against The Columbia Housing AuthorityWIS Digital News Staff100% (1)

- Estate of Jeffrey Scott Lillis v. Correct Care Solutions LLC, Et. Al.Documento42 pagineEstate of Jeffrey Scott Lillis v. Correct Care Solutions LLC, Et. Al.Michael_Lee_RobertsNessuna valutazione finora

- Mark Dixon State of Arizona Notice of Claim 1-12-13 PDFDocumento16 pagineMark Dixon State of Arizona Notice of Claim 1-12-13 PDFfixpinalcountyNessuna valutazione finora

- Specpro Rule 88 FullTextDocumento16 pagineSpecpro Rule 88 FullTextChrissy SabellaNessuna valutazione finora

- In Re: Ottoson-King V., 4th Cir. (2001)Documento7 pagineIn Re: Ottoson-King V., 4th Cir. (2001)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- 74 - WT Construction V DPWHDocumento2 pagine74 - WT Construction V DPWHJanine Castro100% (1)

- Metropolitan Bank and Trust Co. v. Junnel S20210424-12-1eaq3pcDocumento17 pagineMetropolitan Bank and Trust Co. v. Junnel S20210424-12-1eaq3pcmarie janNessuna valutazione finora

- Albert Moehring v. The Bank of New York Mellon, 4th Cir. (2014)Documento2 pagineAlbert Moehring v. The Bank of New York Mellon, 4th Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Transpo (Bill of Lading)Documento9 pagineTranspo (Bill of Lading)Riccia VillamorNessuna valutazione finora

- Bustos vs. Millians Shoe, Inc.Documento12 pagineBustos vs. Millians Shoe, Inc.Krystal Grace D. PaduraNessuna valutazione finora

- Petition For Special Action With Arizona Supreme CourtDocumento27 paginePetition For Special Action With Arizona Supreme CourtKevin StoneNessuna valutazione finora

- Continuation of Choice of Law in Saudi Arabian Airlines vs Court of AppealsDocumento143 pagineContinuation of Choice of Law in Saudi Arabian Airlines vs Court of AppealsNeyann PotridoNessuna valutazione finora

- Witness and Exhibit List - Doc 19Documento6 pagineWitness and Exhibit List - Doc 19Dentist The MenaceNessuna valutazione finora

- 16 18 Election Law CasesDocumento2 pagine16 18 Election Law CasescarlNessuna valutazione finora

- Actual Semi Truck Complaint SampleDocumento10 pagineActual Semi Truck Complaint SampleShirley WeissNessuna valutazione finora

- HUMAN RELATIONS CASE ANALYSISDocumento5 pagineHUMAN RELATIONS CASE ANALYSISErika Mariz CunananNessuna valutazione finora

- Succession Cases 774-795Documento51 pagineSuccession Cases 774-795Jan Maxine PalomataNessuna valutazione finora

- Order For Release of Tommy Frederick AllanDocumento1 paginaOrder For Release of Tommy Frederick AllanABC10Nessuna valutazione finora

- TAX AGENTS SEMINAR ON ASSESSMENT AND COLLECTIONDocumento37 pagineTAX AGENTS SEMINAR ON ASSESSMENT AND COLLECTIONMarco Fernando Lumanlan NgNessuna valutazione finora

- BIR V CADocumento3 pagineBIR V CADominic Estremos100% (1)

- Lancer Motel LawsuitDocumento12 pagineLancer Motel LawsuitABC15 NewsNessuna valutazione finora

- Medina v. Greenfield Development Corp.Documento7 pagineMedina v. Greenfield Development Corp.RubyNessuna valutazione finora

- Expropriation in EuropeDocumento31 pagineExpropriation in EuropeCentar za ustavne i upravne studije100% (1)

- Intervention,: (G.R. No. 155001. May 5, 2003)Documento157 pagineIntervention,: (G.R. No. 155001. May 5, 2003)Dara CompuestoNessuna valutazione finora

- PHIVIDEC v. Court of Appeals, 181 SCRA 669 (1990)Documento11 paginePHIVIDEC v. Court of Appeals, 181 SCRA 669 (1990)inno KalNessuna valutazione finora

- Cases For Civil Law Review (Torts and Damages)Documento3 pagineCases For Civil Law Review (Torts and Damages)ervingabralagbonNessuna valutazione finora

- Conflicts of LawDocumento7 pagineConflicts of LawAlexPamintuanAbitanNessuna valutazione finora

- Remedies of Gov'T-statute of LimitationsDocumento194 pagineRemedies of Gov'T-statute of LimitationsAnne AbelloNessuna valutazione finora

- NIL Digested CasesDocumento11 pagineNIL Digested CasestatskoplingNessuna valutazione finora

- Evidence Compiled CasesDocumento13 pagineEvidence Compiled CasesKelsey Olivar MendozaNessuna valutazione finora

- 21 Skyi V BegasaDocumento10 pagine21 Skyi V BegasaMaggi BonoanNessuna valutazione finora

- Smith V Ebay ComplaintDocumento20 pagineSmith V Ebay ComplaintEric GoldmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Sarah Palin New York Times LawsuitDocumento25 pagineSarah Palin New York Times LawsuitThe Daily DotNessuna valutazione finora

- Traders Royal Bank vs. CA, 269 SCRA 16, March 3, 1997Documento9 pagineTraders Royal Bank vs. CA, 269 SCRA 16, March 3, 1997XuagramellebasiNessuna valutazione finora

- Home Insurance Co. v. Eastern Shipping LinesDocumento6 pagineHome Insurance Co. v. Eastern Shipping LinesSecret BookNessuna valutazione finora

- New York State Department of Environmental Conservation LetterDocumento18 pagineNew York State Department of Environmental Conservation LetterDaily FreemanNessuna valutazione finora

- 219 Scra 736Documento2 pagine219 Scra 736Rhuejane Gay MaquilingNessuna valutazione finora

- Wyoming Marijuana InitiativesDocumento20 pagineWyoming Marijuana InitiativesMarijuana Moment100% (1)

- Case Digests in Insurance Daryll Gayle Asuncion October 4, 2018Documento9 pagineCase Digests in Insurance Daryll Gayle Asuncion October 4, 2018Daryll Gayle AsuncionNessuna valutazione finora

- Abraham Tolentino vs. Comelec, GR 187958 (April 7, 2010)Documento21 pagineAbraham Tolentino vs. Comelec, GR 187958 (April 7, 2010)Simon ZgdNessuna valutazione finora

- TORTS AND DAMAGES BATCH 1 CASEDocumento68 pagineTORTS AND DAMAGES BATCH 1 CASERaikha D. BarraNessuna valutazione finora

- Wiegel v. Sempio-DyDocumento1 paginaWiegel v. Sempio-DyElaine HonradeNessuna valutazione finora

- CFC - Amended Verified Petition - 5.6.11Documento124 pagineCFC - Amended Verified Petition - 5.6.11sammyschwartz08Nessuna valutazione finora

- Majeure. It Was Also Elevated To SC and Was Sustained. Hence, Court Needs To Reconcile TheDocumento6 pagineMajeure. It Was Also Elevated To SC and Was Sustained. Hence, Court Needs To Reconcile TheI.G. Mingo MulaNessuna valutazione finora

- Debt Collection Lawsuit Alleges Excessive CallsDocumento4 pagineDebt Collection Lawsuit Alleges Excessive CallsPipes B.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Commerce Bank, Et Al. v. Bank of New York MellonDocumento69 pagineCommerce Bank, Et Al. v. Bank of New York MellonIsaac GradmanNessuna valutazione finora

- James Robert Altizer Petition For A Writ of Actual Innocence in The Virginia Court of AppealsDocumento12 pagineJames Robert Altizer Petition For A Writ of Actual Innocence in The Virginia Court of AppealsJordan FiferNessuna valutazione finora

- 32 Aguila Vs BaldovizoDocumento7 pagine32 Aguila Vs BaldovizoDawn Jessa GoNessuna valutazione finora

- 2nd Half Cases-Rulings OnlyDocumento39 pagine2nd Half Cases-Rulings OnlyalyssamaesanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Heirs of Maramag V Maramag Et Al.Documento4 pagineHeirs of Maramag V Maramag Et Al.Alexandria ThiamNessuna valutazione finora

- Oblicon Digests (Finals1)Documento21 pagineOblicon Digests (Finals1)Concon FabricanteNessuna valutazione finora

- White v. National Bank, 102 U.S. 658 (1881)Documento6 pagineWhite v. National Bank, 102 U.S. 658 (1881)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Premiere Development Bank V Flores 574 SCRA 66Documento10 paginePremiere Development Bank V Flores 574 SCRA 66sunsetsailor85Nessuna valutazione finora

- RESTITUTA M. IMPERIAL, Petitioner, vs. ALEX A. JAUCIAN, Respondent. G.R. No. 149004 April 14, 2004 Panganiban, J.: FactsDocumento2 pagineRESTITUTA M. IMPERIAL, Petitioner, vs. ALEX A. JAUCIAN, Respondent. G.R. No. 149004 April 14, 2004 Panganiban, J.: FactsAdi LimNessuna valutazione finora

- Banking law ruling on liability for failed loan takeoverDocumento2 pagineBanking law ruling on liability for failed loan takeoverAdi LimNessuna valutazione finora

- Rules 39 61 2Documento94 pagineRules 39 61 2Enric AlcaideNessuna valutazione finora

- Ancient PhilosophyDocumento6 pagineAncient PhilosophyKeith BalbinNessuna valutazione finora

- Protection of Victims PDFDocumento16 pagineProtection of Victims PDFKeith BalbinNessuna valutazione finora

- A. Individual Performance Commitment Review (Ipcr)Documento4 pagineA. Individual Performance Commitment Review (Ipcr)GretchenNessuna valutazione finora

- TEN Steps To Be Undertaken in The Correction of An Entry in A Civil Registry DocumentDocumento2 pagineTEN Steps To Be Undertaken in The Correction of An Entry in A Civil Registry DocumentKeith BalbinNessuna valutazione finora

- Law On Agency (Business Organization 1) ADMUDocumento66 pagineLaw On Agency (Business Organization 1) ADMUMaria Cecilia Oliva100% (1)

- Reyes V AlmanzorDocumento17 pagineReyes V AlmanzorKeith BalbinNessuna valutazione finora

- Red Alert 2 Yuri Revenge Maps 1138 Maps Mega Pack ListDocumento19 pagineRed Alert 2 Yuri Revenge Maps 1138 Maps Mega Pack ListKeith Balbin20% (5)

- Mr. President Addressed as Head of StateDocumento7 pagineMr. President Addressed as Head of StateKeith Balbin100% (1)

- RTC Incumbent JudgesDocumento24 pagineRTC Incumbent JudgesRaymond RamseyNessuna valutazione finora

- CIR v. Santos Rules on RTC Authority to Review Tax PolicyDocumento1 paginaCIR v. Santos Rules on RTC Authority to Review Tax PolicyKeith Balbin100% (3)

- Retroactive Tax IncreaseDocumento3 pagineRetroactive Tax IncreaseKeith BalbinNessuna valutazione finora

- Tax I Assignment of CasesDocumento2 pagineTax I Assignment of CasesKeith BalbinNessuna valutazione finora

- Retroactive Tax IncreaseDocumento3 pagineRetroactive Tax IncreaseKeith BalbinNessuna valutazione finora

- 18 Tan V Del Rosario 237 SCRA 324 (1994) - DigestDocumento15 pagine18 Tan V Del Rosario 237 SCRA 324 (1994) - DigestKeith BalbinNessuna valutazione finora

- Tax DigestDocumento3 pagineTax DigestKeith BalbinNessuna valutazione finora

- American Assurance V TantucoDocumento9 pagineAmerican Assurance V TantucoKeith BalbinNessuna valutazione finora

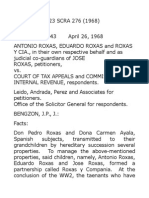

- 16 Roxas V CTA 23 SCRA 276 (1968) - DigestDocumento8 pagine16 Roxas V CTA 23 SCRA 276 (1968) - DigestKeith Balbin0% (1)

- CIR v. Santos Rules on RTC Authority to Review Tax PolicyDocumento1 paginaCIR v. Santos Rules on RTC Authority to Review Tax PolicyKeith Balbin100% (3)

- Tax DigestDocumento3 pagineTax DigestKeith BalbinNessuna valutazione finora

- Tax DigestDocumento3 pagineTax DigestKeith BalbinNessuna valutazione finora

- MLA Vs Vera Tabios DigestDocumento2 pagineMLA Vs Vera Tabios DigestKeith BalbinNessuna valutazione finora

- PNP Manual PDFDocumento114 paginePNP Manual PDFIrish PD100% (9)

- Philippine National Bank vs. Aznar GR 171805Documento9 paginePhilippine National Bank vs. Aznar GR 171805Keith BalbinNessuna valutazione finora

- Writ and Some of Its Classifications PDFDocumento5 pagineWrit and Some of Its Classifications PDFKeith BalbinNessuna valutazione finora

- Book 2 Some Major Philippine Court CasesDocumento59 pagineBook 2 Some Major Philippine Court CasesKeith BalbinNessuna valutazione finora

- Supreme Court Rules on Annulment of Sale of Real PropertyDocumento13 pagineSupreme Court Rules on Annulment of Sale of Real PropertyKeith BalbinNessuna valutazione finora

- Succession Cases Ratio With Case DigestDocumento16 pagineSuccession Cases Ratio With Case DigestKeith BalbinNessuna valutazione finora

- Pasinio vs. Monterroyo GR 159494Documento12 paginePasinio vs. Monterroyo GR 159494Keith BalbinNessuna valutazione finora

- Wenphil Corp. vs. NLRC GR 80587Documento5 pagineWenphil Corp. vs. NLRC GR 80587Keith BalbinNessuna valutazione finora

- Exam Taker Answer ReportDocumento3 pagineExam Taker Answer ReportAvelino PagandiyanNessuna valutazione finora

- A Barangay Ordinance Requiring All Sari-Sari Store, FoodDocumento3 pagineA Barangay Ordinance Requiring All Sari-Sari Store, Fooddon cong90% (10)

- FPSC LOCATIONSDocumento1 paginaFPSC LOCATIONSjazib1200Nessuna valutazione finora

- President's Power of Supervision vs Control Over Liga ng Barangay ElectionsDocumento2 paginePresident's Power of Supervision vs Control Over Liga ng Barangay ElectionsJaja Gk100% (2)

- AlHakam 13 OctDocumento24 pagineAlHakam 13 OctaliNessuna valutazione finora

- Osg V. Ayala Land IncDocumento23 pagineOsg V. Ayala Land IncGLORILYN MONTEJONessuna valutazione finora

- Simple Steps For A Simple TempleDocumento50 pagineSimple Steps For A Simple TempleJagad-Guru DasNessuna valutazione finora

- BAR - Urban - Ops - Volume 1Documento188 pagineBAR - Urban - Ops - Volume 1Darko BozicNessuna valutazione finora

- Standard Lifting Lug Horizontal TankDocumento3 pagineStandard Lifting Lug Horizontal TankJericNessuna valutazione finora

- Political Ideology Liberal Conservative and ModerateDocumento30 paginePolitical Ideology Liberal Conservative and ModerateAdriane Morriz A Gusabas100% (1)

- Crank Case Explosion PDFDocumento1 paginaCrank Case Explosion PDFJoherNessuna valutazione finora

- Moyles Et Al. v. Johnson Controls, Inc. - Document No. 9Documento2 pagineMoyles Et Al. v. Johnson Controls, Inc. - Document No. 9Justia.comNessuna valutazione finora

- Judicial Affidavit RuleDocumento8 pagineJudicial Affidavit RuleAPRIL ROSE YOSORESNessuna valutazione finora

- Implementation of Nec and National Conference Resolution Regarding Members Charged With CorruptionDocumento20 pagineImplementation of Nec and National Conference Resolution Regarding Members Charged With CorruptionLisle Daverin BlythNessuna valutazione finora

- M M SpeechDocumento2 pagineM M SpeechAna SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Concept of MarriageDocumento9 pagineConcept of MarriageCentSeringNessuna valutazione finora

- Satterfield LawsuitDocumento13 pagineSatterfield LawsuitJazmine Ashley Greene100% (3)

- The Great Chanakya Neethi SutrasDocumento10 pagineThe Great Chanakya Neethi SutrasManjunath HrmNessuna valutazione finora

- Madhya Pradesh HC's Judgment On Wife Entitled To Know Husbands SalaryDocumento5 pagineMadhya Pradesh HC's Judgment On Wife Entitled To Know Husbands SalaryLatest Laws TeamNessuna valutazione finora

- Choose correct verb tenses for sentencesDocumento5 pagineChoose correct verb tenses for sentencesNova SetiajiNessuna valutazione finora

- Comparing Russian and Chinese Views of Colour RevolutionsDocumento21 pagineComparing Russian and Chinese Views of Colour Revolutionssahar231Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lea El Siguiente Texto y Desarrolle Las ActividadesDocumento2 pagineLea El Siguiente Texto y Desarrolle Las ActividadesAnne Marie Velasquez0% (2)

- SUYOG2604Documento1 paginaSUYOG2604vishalNessuna valutazione finora

- PD 223Documento4 paginePD 223Catly CapistranoNessuna valutazione finora

- River V People DigestDocumento2 pagineRiver V People DigestBenilde DungoNessuna valutazione finora

- Hospital HistoryDocumento25 pagineHospital HistoryTeresita BalgosNessuna valutazione finora

- Reaction Paper (Actofproclamation)Documento1 paginaReaction Paper (Actofproclamation)Michael AngelesNessuna valutazione finora

- Be It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippine Congress AssembledDocumento2 pagineBe It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippine Congress AssembledMikka MonesNessuna valutazione finora

- Sigmund Freud's Psychoanalytic TheoryDocumento4 pagineSigmund Freud's Psychoanalytic TheoryMary Joy CornelioNessuna valutazione finora

- 44 - Arturo Valenzuela Vs CADocumento1 pagina44 - Arturo Valenzuela Vs CAperlitainocencioNessuna valutazione finora