Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Brahmo Samaj

Caricato da

satya8092Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Brahmo Samaj

Caricato da

satya8092Copyright:

Formati disponibili

As a member of the Brahmo Samaj, Narendra accepted its doctrine of monotheism an

d

the Personal God. He also believed in the natural depravity of man. Such doctrin

es of

non-dualistic Vedanta as the divinity of the soul and the oneness of existence h

e

regarded as blasphemy; the view that man is one with God appeared to him pure

nonsense. When the master warned him against thus limiting God's infinitude and

asked him to pray to God to reveal to him His true nature, Narendra smiled. One

day

he was making fun of Sri Ramakrishna's non-dualism before a friend and said, 'Wh

at

can be more absurd than to say that this jug is God, this cup is God, and that w

e too are

God?' Both roared with laughter.

Just then the Master appeared. Coming to learn the cause of their fun, he gently

touched Naren and plunged into deep samadhi. The touch produced a magic effect,

and

Narendra entered a new realm of consciousness. He saw the whole universe permeat

ed

by the Divine Spirit and returned home in a daze. While eating his meal, he felt

the

presence of Brahman in everything in the food, and in himself too. While walking

in the street, he saw the carriages, the horses, the crowd, and himself as if ma

de of the

same substance. After a few days the intensity of the vision lessened to some ex

tent,

but still he could see the world only as a dream. While strolling in a public pa

rk of

Calcutta, he struck his head against the iron railing, several times, to see if

they were

real or a mere illusion of the mind. Thus he got a glimpse of non-dualism, the f

ullest

realization of which was to come only later, at the Cossipore garden.

Sri Ramakrishna was always pleased when his disciples put to the test his statem

ents or

behaviour before accepting his teachings. He would say: 'Test me as the moneycha

ngers

test their coins. You must not believe me without testing me thoroughly.' The

disciples often heard him say that his nervous system had undergone a complete

change as a result of his spiritual experiences, and that he could not bear the

touch of

any metal, such as gold or silver. One day, during his absence in Calcutta, Nare

ndra

hid a coin under Ramakrishna's bed. After his return when the Master sat on the

bed,

he started up in pain as if stung by an insect. The mattress was examined and th

e

hidden coin was found.

Naren, on the other hand, was often tested by the Master. One day, when he enter

ed the

Master's room, he was completely ignored. Not a word of greeting was uttered. A

week

later he came back and met with the same indifference, and during the third and

fourth

visits saw no evidence of any thawing of the Master's frigid attitude.

At the end of a month Sri Ramakrishna said to Naren, 'I have not exchanged a sin

gle

word with you all this time, and still you come.'

The disciple replied: 'I come to Dakshineswar because I love you and want to see

you.

I do not come here to hear your words.'

The Master was overjoyed. Embracing the disciple, he said: 'I was only testing y

ou. I

wanted to see if you would stay away on account of my outward indifference. Only

a

man of your inner strength could put up with such indifference on my part. Anyon

e

else would have left me long ago.'

On one occasion Sri Ramakrishna proposed to transfer to Narendranath many of the

spiritual powers that he had acquired as a result of his ascetic disciplines and

visions of

God. Naren had no doubt concerning the Master's possessing such powers. He asked

if

they would help him to realize God. Sri Ramakrishna replied in the negative but

added

that they might assist him in his future work as a spiritual teacher. 'Let me re

alize God

first,' said Naren, 'and then I shall perhaps know whether or not I want superna

tural

powers. If I accept them now, I may forget God, make selfish use of them, and th

us

come to grief.' Sri Ramakrishna was highly pleased to see his chief disciple's s

ingleminded

devotion.

Several factors were at work to mould the personality of young Narendranath.

Foremost of these were his inborn spiritual tendencies, which were beginning to

show

themselves under the influence of Sri Ramakrishna, but against which his rationa

l mind

put up a strenuous fight. Second was his habit of thinking highly and acting nob

ly,

disciplines acquired from a mother steeped in the spiritual heritage of India. T

hird were

his broadmindedness and regard for truth wherever found, and his sceptical attit

ude

towards the religious beliefs and social conventions of the Hindu society of his

time.

These he had learnt from his English-educated father, and he was strengthened in

them

through his own contact with Western culture.

With the introduction in India of English education during the middle of the nin

eteenth

century, as we have seen, Western science, history, and philosophy were studied

in the

Indian colleges and universities. The educated Hindu youths, allured by the glam

our,

began to mould their thought according to this new light, and Narendra could not

escape the influence. He developed a great respect for the analytical scientific

method

and subjected many of the Master's spiritual visions to such scrutiny. The Engli

sh poets

stirred his feelings, especially Wordsworth and Shelley, and he took a course in

Western medicine to understand the functioning of the nervous system, particular

ly the

brain and spinal cord, in order to find out the secrets of Sri Ramakrishna's tra

nces. But

all this only deepened his inner turmoil.

John Stuart Mill's Three Essays on Religion upset his boyish theism and the easy

optimism imbibed from the Brahmo Samaj. The presence of evil in nature and man

haunted him and he could not reconcile it at all with the goodness of an omnipot

ent

Creator. Hume's scepticism and Herbert Spencer's doctrine of the Unknowable fill

ed

his mind with a settled philosophical agnosticism. After the wearing out of his

first

emotional freshness and naivete, he was beset with a certain dryness and incapac

ity for

the old prayers and devotions. He was filled with an ennui which he concealed,

however, under his jovial nature. Music, at this difficult stage of his life, re

ndered him

great help; for it moved him as nothing else and gave him a glimpse of unseen re

alities

that often brought tears to his eyes.

Narendra did not have much patience with humdrum reading, nor did he care to abs

orb

knowledge from books as much as from living communion and personal experience.

He wanted life to be kindled by life, and thought kindled by thought. He studied

Shelley under a college friend, Brajendranath Seal, who later became the leading

Indian philosopher of his time, and deeply felt with the poet his pantheism, imp

ersonal

love, and vision of a glorified millennial humanity. The universe, no longer a m

ere

lifeless, loveless mechanism, was seen to contain a spiritual principle of unity

.

Brajendranath, moreover, tried to present him with a synthesis of the Supreme

Brahman of Vedanta, the Universal Reason of Hegel, and the gospel of Liberty,

Equality, and Fraternity of the French Revolution. By accepting as the principle

of

morals the sovereignty of the Universal Reason and the negation of the individua

l,

Narendra achieved an intellectual victory over scepticism and materialism, but n

o

peace of mind.

Narendra now had to face a new difficulty. The 'ballet of bloodless categories'

of Hegel

and his creed of Universal Reason required of Naren a suppression of the yearnin

g and

susceptibility of his artistic nature and joyous temperament, the destruction of

the

cravings of his keen and acute senses, and the smothering of his free and merry

conviviality. This amounted almost to killing his own true self. Further, he cou

ld not

find in such a philosophy any help in the struggle of a hot-blooded youth agains

t the

cravings of the passions, which appeared to him as impure, gross, and carnal. So

me of

his musical associates were men of loose morals for whom he felt a bitter and

undisguised contempt.

Narendra therefore asked his friend Brajendra if the latter knew the way of deli

verance

from the bondage of the senses, but he was told only to rely upon Pure Reason an

d to

identify the self with it, and was promised that through this he would experienc

e an

ineffable peace. The friend was a Platonic transcendentalist and did not have fa

ith in

what he called the artificial prop of grace, or the mediation of a guru. But the

problems

and difficulties of Narendra were very different from those of his intellectual

friend.

He found that mere philosophy was impotent in the hour of temptation and in the

struggle for his soul's deliverance. He felt the need of a hand to save, to upli

ft, to

protect shakti or power outside his rational mind that would transform his

impotence into strength and glory. He wanted a flesh-and-blood reality establish

ed in

peace and certainty, in short, a living guru, who, by embodying perfection in th

e flesh,

would compose the commotion of his soul.

The leaders of the Brahmo Samaj, as well as those of the other religious sects,

had

failed. It was only Ramakrishna who spoke to him with authority, as none had spo

ken

before, and by his power brought peace into the troubled soul and healed the wou

nds

of the spirit. At first Naren feared that the serenity that possessed him in the

presence

of the Master was illusory, but his misgivings were gradually vanquished by the

calm

assurance transmitted to him by Ramakrishna out of his own experience of

Satchidananda Brahman Existence, Knowledge, and Bliss Absolute. (This account

of the struggle of Naren's collegiate days summarizes an article on Swami

Vivekananda by Brajendranath Seal, published in the Life of Swami Vivekananda by

the Advaita Ashrama, Mayavati, India.)

Narendra could not but recognize the contrast of the Sturm und Drang of his soul

with

the serene bliss in which Sri Ramakrishna was always bathed. He begged the Maste

r to

teach him meditation, and Sri Ramakrishna's reply was to him a source of comfort

and

strength. The Master said: 'God listens to our sincere prayer. I can swear that

you can

see God and talk with Him as intensely as you see me and talk with me. You can h

ear

His words and feel His touch.' Further the Master declared: 'You may not believe

in

divine forms, but if you believe in an Ultimate Reality who is the Regulator of

the

universe, you can pray to Him thus: "O God, I do not know Thee. Be gracious to r

eveal

to me Thy real nature." He will certainly listen to you if your prayer is sincer

e.'

Narendra, intensifying his meditation under the Master's guidance, began to lose

consciousness of the body and to feel an inner peace, and this peace would linge

r even

after the meditation was over. Frequently he felt the separation of the body fro

m the

soul. Strange perceptions came to him in dreams, producing a sense of exaltation

that

persisted after he awoke. The guru was performing his task in an inscrutable man

ner,

Narendra's friends observed only his outer struggle; but the real transformation

was

known to the teacher alone or perhaps to the disciple too.

In 1884, when Narendranath was preparing for the B.A. examination, his family wa

s

struck by a calamity. His father suddenly died, and the mother and children were

plunged into great grief. For Viswanath, a man of generous nature, had lived bey

ond

his means, and his death burdened the family with a heavy debt. Creditors, like

hungry

wolves, began to prowl about the door, and to make matters worse, certain relati

ves

brought a lawsuit for the partition of the ancestral home. Though they lost it,

Narendra

was faced, thereafter, with poverty. As the eldest male member of the family, he

had to

find the wherewithal for the feeding of seven or eight mouths and began to hunt

a job.

He also attended the law classes. He went about clad in coarse clothes, barefoot

, and

hungry. Often he refused invitations for dinner from friends, remembering his st

arving

mother, brothers, and sisters at home. He would skip family meals on the fictiti

ous plea

that he had already eaten at a friend's house, so that the people at home might

receive a

larger share of the scanty food. The Datta family was proud and would not dream

of

soliciting help from outsiders. With his companions Narendra was his usual gay s

elf.

His rich friends no doubt noticed his pale face, but they did nothing to help. O

nly one

friend sent occasional anonymous aid, and Narendra remained grateful to him for

life.

Meanwhile, all his efforts to find employment failed. Some friends who earned mo

ney

in a dishonest way asked him to join them, and a rich woman sent him an immoral

proposal, promising to put an end to his financial distress. But Narendra gave t

o these a

blunt rebuff. Sometimes he would wonder if the world were not the handiwork

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Man, the Measure of All Things: In the Stanzas of DzyanDa EverandMan, the Measure of All Things: In the Stanzas of DzyanNessuna valutazione finora

- Selections from the Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna: Translated byDa EverandSelections from the Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna: Translated byNessuna valutazione finora

- Self - Knowledge - Swami Nikhilananda 1947Documento342 pagineSelf - Knowledge - Swami Nikhilananda 1947kairali123Nessuna valutazione finora

- Chakrapani Ullal Friend and MentorDocumento11 pagineChakrapani Ullal Friend and MentormichaNessuna valutazione finora

- Swami Vivekananda and The Psychic PowersDocumento5 pagineSwami Vivekananda and The Psychic PowersSagar Sharma100% (3)

- Prophets of New India: Book I: RamakrishnaDocumento11 pagineProphets of New India: Book I: RamakrishnaSatyendra Nath DwivediNessuna valutazione finora

- Crest-Jewel of DiscriminationDocumento147 pagineCrest-Jewel of Discriminationdadwhiskers100% (2)

- Necessity For Sannyasa SivanandaDocumento64 pagineNecessity For Sannyasa SivanandaPetar SimonovicNessuna valutazione finora

- Integral Yoga in Swami Vivekananda ( ) : Published in The Vedanta Kesari Magazine - Jan 1977 Page 281Documento8 pagineIntegral Yoga in Swami Vivekananda ( ) : Published in The Vedanta Kesari Magazine - Jan 1977 Page 281Sara RussellNessuna valutazione finora

- Project Swami0202Documento55 pagineProject Swami0202GLOBAL INFO-TECH KUMBAKONAMNessuna valutazione finora

- Deep MeditationDocumento4 pagineDeep MeditationYou Are Not Wasting TIME HereNessuna valutazione finora

- An Encounter Between The Holy and The Lowly - Adi Sankara's Maneesha PanchakamDocumento4 pagineAn Encounter Between The Holy and The Lowly - Adi Sankara's Maneesha Panchakamnarasimma8313Nessuna valutazione finora

- Swami Vivekananda:his Life & MissionDocumento29 pagineSwami Vivekananda:his Life & Missionritam020719881088Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ebook - 84 Mahassidas PDFDocumento119 pagineEbook - 84 Mahassidas PDFJohnW1689100% (3)

- The Divine ProfileDocumento6 pagineThe Divine Profileapi-26172340Nessuna valutazione finora

- Srila Prabhupadas Beautiful Ttranscendental Qualities 26 CC Madhya 22.78-80Documento31 pagineSrila Prabhupadas Beautiful Ttranscendental Qualities 26 CC Madhya 22.78-80jkmadaanNessuna valutazione finora

- Crazy Wisdom of the Yogini: Teachings of the Kashmiri Mahamudra TraditionDa EverandCrazy Wisdom of the Yogini: Teachings of the Kashmiri Mahamudra TraditionValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- MaalokDocumento36 pagineMaalokganesh_b019191Nessuna valutazione finora

- Secrets of Left-Hand Tantra: Atmatattva DasDocumento7 pagineSecrets of Left-Hand Tantra: Atmatattva DasShankarananda Sher100% (1)

- Sri Sharada Devi - The Embodiment of PurityDocumento20 pagineSri Sharada Devi - The Embodiment of PuritySwami VedatitanandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Introd UctionDocumento3 pagineIntrod UctionmukadeNessuna valutazione finora

- 15 Popular Saints of Bhakti Movement - Medieval IndiaDocumento19 pagine15 Popular Saints of Bhakti Movement - Medieval IndiaMadhusmita SwainNessuna valutazione finora

- Tantric Quest: An Encounter with Absolute LoveDa EverandTantric Quest: An Encounter with Absolute LoveValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (9)

- New 4Documento3 pagineNew 4vX2537Nessuna valutazione finora

- Thakur Anukulchandra An OverviewDocumento17 pagineThakur Anukulchandra An Overviewapi-26172340Nessuna valutazione finora

- Yoga Spandakarika: The Sacred Texts at the Origins of TantraDa EverandYoga Spandakarika: The Sacred Texts at the Origins of TantraValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (5)

- Swami VivekanandDocumento13 pagineSwami Vivekanandlalitchanchar970Nessuna valutazione finora

- Self-Inquiry in Adi Sankara's Works Pof Lulu 6x9 11-4-2012Documento96 pagineSelf-Inquiry in Adi Sankara's Works Pof Lulu 6x9 11-4-2012Suryanarayana Raju100% (2)

- My Search For Truth - Formative Years Dr. S. RadhakrishnanDocumento8 pagineMy Search For Truth - Formative Years Dr. S. Radhakrishnanharikams88Nessuna valutazione finora

- DNYANESHWARIDocumento10 pagineDNYANESHWARIAmol ModakNessuna valutazione finora

- Five - Interviews - David GodmanDocumento144 pagineFive - Interviews - David Godmanvivekns100% (1)

- Editorials of Vedanta Kesari - Volume 51Documento69 pagineEditorials of Vedanta Kesari - Volume 51api-19985927Nessuna valutazione finora

- Two Saints: Speculations Around and About Ramakrishna Paramahamsa and Ramana MaharishiDa EverandTwo Saints: Speculations Around and About Ramakrishna Paramahamsa and Ramana MaharishiNessuna valutazione finora

- 15 Popular Saints of Bhakti Movement Medival IndiaDocumento9 pagine15 Popular Saints of Bhakti Movement Medival IndiaAnonymous Rs28Sn100% (1)

- Learn To Behave - YGDocumento8 pagineLearn To Behave - YGRohit DeshpandeNessuna valutazione finora

- Swami Vivekananda AND HIS Political ThoughtDocumento19 pagineSwami Vivekananda AND HIS Political Thought12590adnankhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Enlightenment: Where Kabir, Zen Philosophy and Cho Oh-Hyun Get Synchronized Er. Shreyaskar GaurDocumento7 pagineEnlightenment: Where Kabir, Zen Philosophy and Cho Oh-Hyun Get Synchronized Er. Shreyaskar GaurSanatan SinhNessuna valutazione finora

- Sadhu Santinatha - Experiences of A Truth-SeekerDocumento552 pagineSadhu Santinatha - Experiences of A Truth-SeekerBirgi Zorgony100% (1)

- LightDocumento106 pagineLightGlory of Sanatan Dharma Scriptures & KnowledgeNessuna valutazione finora

- Sri Adi ShankaracharyaDocumento11 pagineSri Adi ShankaracharyaNiharikaBishtNessuna valutazione finora

- Swami Vivekananda: The Charm of His Personality and MessageDa EverandSwami Vivekananda: The Charm of His Personality and MessageNessuna valutazione finora

- Vallalar Messanger of Grace LightDocumento150 pagineVallalar Messanger of Grace LightNikki*89% (9)

- Paramahansa Srimat Swami Nigamananda Saraswati DevDocumento7 pagineParamahansa Srimat Swami Nigamananda Saraswati DevjoydurgaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sri Shankara DigvijayamDocumento27 pagineSri Shankara Digvijayamramkumaran100% (3)

- God Lived With ThemDocumento28 pagineGod Lived With ThemJames ClarkNessuna valutazione finora

- Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj - Seeds of ConsciousnessDocumento108 pagineSri Nisargadatta Maharaj - Seeds of ConsciousnessSanjeev Gupta100% (5)

- Ramayana Mahabharata QuestionsDocumento5 pagineRamayana Mahabharata Questionsshivayog5Nessuna valutazione finora

- Swami Vivekananda IVDocumento13 pagineSwami Vivekananda IVSatyendra Nath DwivediNessuna valutazione finora

- Passion To Compassion: " Savai Pumsham Paro Dharmo Eto Bhaktir Adokshaje Ahetuki Apratihata Ea Atatma Suprasidati"Documento5 paginePassion To Compassion: " Savai Pumsham Paro Dharmo Eto Bhaktir Adokshaje Ahetuki Apratihata Ea Atatma Suprasidati"Sudhir BabuNessuna valutazione finora

- Extra Samskara ThemesDocumento17 pagineExtra Samskara ThemesAisha RahatNessuna valutazione finora

- Jnana Yoga of Sri Ramana MaharshiDocumento4 pagineJnana Yoga of Sri Ramana Maharshijne6379Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sant Dnyaneshwar - Beyond Brahmanical Tyrannye Warkari Movement I Sant DnyaneshwarDocumento4 pagineSant Dnyaneshwar - Beyond Brahmanical Tyrannye Warkari Movement I Sant DnyaneshwarRupa AbdiNessuna valutazione finora

- Bhagavan Sri Ramana MaharshiDocumento18 pagineBhagavan Sri Ramana MaharshirangaNessuna valutazione finora

- Narad Bhakti SutraDocumento25 pagineNarad Bhakti Sutraprakas.rao39695Nessuna valutazione finora

- Krishna The God Who Lives As Man - Bhawana SommayaDocumento228 pagineKrishna The God Who Lives As Man - Bhawana SommayaCristianoluc100% (2)

- Tattva PrabodhiniDocumento88 pagineTattva PrabodhiniJack LagerNessuna valutazione finora

- More Than 100 Keyboard Shortcuts Must ReadDocumento3 pagineMore Than 100 Keyboard Shortcuts Must ReadChenna Keshav100% (1)

- Ae Mere Humsafar Mp3 Lyrics SongDocumento2 pagineAe Mere Humsafar Mp3 Lyrics Songsatya8092Nessuna valutazione finora

- Belonging To The BrahminDocumento3 pagineBelonging To The Brahminsatya8092Nessuna valutazione finora

- Earticle Airtel 3G Udp 2015Documento1 paginaEarticle Airtel 3G Udp 2015AniketKoleyNessuna valutazione finora

- More Than 100 Keyboard Shortcuts Must ReadDocumento3 pagineMore Than 100 Keyboard Shortcuts Must ReadChenna Keshav100% (1)

- Air 3G Trick 2016Documento1 paginaAir 3G Trick 2016satya8092Nessuna valutazione finora

- Optical Satellite ComunicationsDocumento38 pagineOptical Satellite Comunicationssatya8092Nessuna valutazione finora

- ImpressionDocumento4 pagineImpressionsatya8092Nessuna valutazione finora

- More Than 100 Keyboard Shortcuts Must ReadDocumento3 pagineMore Than 100 Keyboard Shortcuts Must ReadChenna Keshav100% (1)

- Simulation and Speed Control of Induction Motor DrivesDocumento76 pagineSimulation and Speed Control of Induction Motor DrivesNWALLL67% (3)

- EducationDocumento5 pagineEducationsatya8092Nessuna valutazione finora

- English EducationDocumento5 pagineEnglish Educationsatya8092Nessuna valutazione finora

- Datta Family of CalcuttaDocumento4 pagineDatta Family of CalcuttaSylvesterJuniorNessuna valutazione finora

- Adi Godrej ProjectDocumento12 pagineAdi Godrej Projectsatya8092Nessuna valutazione finora

- Aggressive European CultureDocumento2 pagineAggressive European Culturesatya8092Nessuna valutazione finora

- European CultureDocumento2 pagineEuropean Culturesatya8092Nessuna valutazione finora

- SamajDocumento4 pagineSamajsatya8092Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Parliament of ReligionsDocumento3 pagineThe Parliament of Religionssatya8092Nessuna valutazione finora

- The ParliamentDocumento2 pagineThe Parliamentsatya8092Nessuna valutazione finora

- Conclusion of His SpeechDocumento3 pagineConclusion of His Speechsatya8092100% (1)

- ImpressDocumento4 pagineImpresssatya8092Nessuna valutazione finora

- ComprehensionDocumento5 pagineComprehensionsatya8092Nessuna valutazione finora

- Aggressive European CultureDocumento2 pagineAggressive European Culturesatya8092Nessuna valutazione finora

- Limiting GodDocumento5 pagineLimiting Godsatya8092Nessuna valutazione finora

- TrainingDocumento3 pagineTrainingsatya8092Nessuna valutazione finora

- Embodiment of NarayanaDocumento3 pagineEmbodiment of Narayanasatya8092Nessuna valutazione finora

- Impersonal RealityDocumento3 pagineImpersonal Realitysatya8092Nessuna valutazione finora

- ConsolationDocumento2 pagineConsolationsatya8092Nessuna valutazione finora

- NarendraDocumento2 pagineNarendrasatya8092Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson 1 - Introduction To WorldviewsDocumento13 pagineLesson 1 - Introduction To WorldviewsRobert Grice, Ph.D.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Angels and Angelology in The Middle AgesDocumento271 pagineAngels and Angelology in The Middle Agesanon100% (5)

- UparatiDocumento8 pagineUparatiGeetha RamanathanNessuna valutazione finora

- S Antonii Mariæ ZachariaDocumento2 pagineS Antonii Mariæ ZachariaDavid WerlingNessuna valutazione finora

- SerapisDocumento5 pagineSerapisОктай СтефановNessuna valutazione finora

- Form 137 RequestDocumento2 pagineForm 137 RequestElsa CastanedaNessuna valutazione finora

- England Before English-151Documento24 pagineEngland Before English-151sahar JamilNessuna valutazione finora

- Gerhard Eaton, Richard M. Bowering, Gerhard - Sufis of Bijapur, 1300-1700 - Social Roles ofDocumento3 pagineGerhard Eaton, Richard M. Bowering, Gerhard - Sufis of Bijapur, 1300-1700 - Social Roles ofashfaqamarNessuna valutazione finora

- Friday Bulletin 609Documento5 pagineFriday Bulletin 609Ummah_KenyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Despiritualization A Central Theme in Western Thought by Oba T ShakaDocumento10 pagineDespiritualization A Central Theme in Western Thought by Oba T ShakaAtyeb Ba Atum Re100% (2)

- Course: Citizenship Education and Community Engagement (8606) Level: B.Ed (1.5/2.5 Years) Semester: Autumn, 2022Documento13 pagineCourse: Citizenship Education and Community Engagement (8606) Level: B.Ed (1.5/2.5 Years) Semester: Autumn, 2022عابد حسینNessuna valutazione finora

- Matthew Anderson - Presbyterianism - Its Relation To The Negro (1897)Documento292 pagineMatthew Anderson - Presbyterianism - Its Relation To The Negro (1897)chyoungNessuna valutazione finora

- Reviewer ContempDocumento7 pagineReviewer ContempJeus Benedict DalisayNessuna valutazione finora

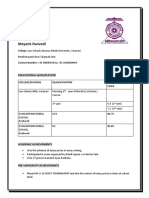

- Mayank Dwivedi CV RealDocumento3 pagineMayank Dwivedi CV RealAshutosh Singh ParmarNessuna valutazione finora

- Grade 6 - Akhlaq BookDocumento90 pagineGrade 6 - Akhlaq BookImammiyah HallNessuna valutazione finora

- Theo 141 Final PDFDocumento8 pagineTheo 141 Final PDFlrpongNessuna valutazione finora

- Archangels of Light TeamDocumento5 pagineArchangels of Light TeamPippo Cipollino100% (2)

- Lambert Dolphin 5 13 14 FinalDocumento7 pagineLambert Dolphin 5 13 14 Finalapi-369102829Nessuna valutazione finora

- Windelband, History of Philosophy, Vol. 2Documento390 pagineWindelband, History of Philosophy, Vol. 2maivin2100% (3)

- NLE 12-2012 ResultsDocumento359 pagineNLE 12-2012 ResultsPRC Baguio0% (2)

- Novalis - MonologDocumento1 paginaNovalis - MonologJohanSanzTerreNessuna valutazione finora

- Islamic Lectures: Mawaiz e AshrafiyaDocumento36 pagineIslamic Lectures: Mawaiz e Ashrafiyanomanpur100% (1)

- Pa 1Documento24 paginePa 1PoorviStrNessuna valutazione finora

- Sutta Discovery: T L W BDocumento3 pagineSutta Discovery: T L W BkatnavNessuna valutazione finora

- Bakhabar: Talking About Your GoalsDocumento32 pagineBakhabar: Talking About Your GoalsbiharanjumanNessuna valutazione finora

- Viewing Robin Hood and Anonymous As Embodiments of Non-Conformity: A Comparative Analysis of Media-Texts Used For Provoking Thoughts of Protest, Disobedience and IdealismDocumento23 pagineViewing Robin Hood and Anonymous As Embodiments of Non-Conformity: A Comparative Analysis of Media-Texts Used For Provoking Thoughts of Protest, Disobedience and IdealismJonathan BishopNessuna valutazione finora

- MBA (Management by Astrology) : A Theoretical FrameworkDocumento7 pagineMBA (Management by Astrology) : A Theoretical FrameworkAnonymous EnIdJONessuna valutazione finora

- AlGhazali and Logic Islamic LawDocumento15 pagineAlGhazali and Logic Islamic LawÖzcan AkdağNessuna valutazione finora

- Rosicrucian Digest, December 1955Documento44 pagineRosicrucian Digest, December 1955sauron385Nessuna valutazione finora

- Keys To Strengthening The Ranks of The SalafeesDocumento5 pagineKeys To Strengthening The Ranks of The SalafeesAbu Adam FinchNessuna valutazione finora