Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Joseph Alois Schumpeter

Caricato da

Ally Gelay0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

138 visualizzazioni46 pagineEconomics

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

DOCX, PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoEconomics

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato DOCX, PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

138 visualizzazioni46 pagineJoseph Alois Schumpeter

Caricato da

Ally GelayEconomics

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato DOCX, PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 46

Joseph Alois

Schumpeter (German: [mpet]; 8

February 1883 8 January 1950)

[1]

was

an Austrian

American economist andpolitical scientist.

He briefly served as Finance Minister of

Austria in 1919. In 1932 he became a

professor at Harvard University where he

remained until the end of his career. One of

the most influential economists of the 20th

century, Schumpeter popularized the term

"creative destruction" in economics.

[2]

Contents

[hide]

1 Life

2 Central contributions

o 2.1 Influences

o 2.2 Evolutionary economics

o 2.3 History of Economic Analysis

o 2.4 Business cycles

o 2.5 Keynesianism

o 2.6 Capitalism's demise

o 2.7 Democratic theory

o 2.8 Entrepreneurship

o 2.9 Cycles and long wave theory

o 2.10 Innovation

3 Legacy

4 Major works

5 See also

6 References

7 Further reading

8 External links

Life[edit]

Schumpeter was born in Te, Habsburg

Moravia (now Czech Republic, then part

of Austria-Hungary) in 1883

to Catholic German-speaking parents. His

father owned a factory, but he died when

Joseph was only four years old.

[3]

In 1893,

Joseph and his mother moved to Vienna.

[4]

Schumpeter began his career studying law

at the University of Vienna under

the Austrian capital theorist Eugen von

Bhm-Bawerk, taking his PhD in 1906. In

1909, after some study trips, he became a

professor of economics and government at

the University of Czernowitz. In 1911 he

joined the University of Graz, where he

remained until World War I. In 1919, he

served briefly as the Austrian Minister of

Finance, with some success, and in 1920

1924, as president of the private

Biedermann Bank. That bank, along with a

great part of that regional economy,

collapsed in 1924 leaving Schumpeter

bankrupt.

From 1925 to 1932, Schumpeter held a

chair at the University of Bonn, Germany.

He lectured at Harvard in 19271928 and

1930. In 1931, he was a visiting professor

at The Tokyo College of Commerce. In

1932, Schumpeter moved to the United

States, and soon began what would

become extensive efforts to help central

European economist colleagues displaced

by Nazism.

[5]

Schumpeter also became

known for his opposition to Marxism and

socialism that he thought would lead to

dictatorship, and even criticized

President Franklin Roosevelt's New

Deal.

[6]

In 1939 Schumpeter became a US

citizen. In the beginning of WWII, the FBI

investigated him and his wife (a prominent

scholar of Japanese economics) for pro-

Nazi leanings, but no evidence was found

of Nazi sympathies.

[7][8]

During his Harvard years Schumpeter was

considered a memorable character, erudite

and even showy as classroom teacher. He

became known for his heavy teaching load,

as well as for taking a personal and

painstaking interest in his students, and

organizing private seminars and discussion

groups in addition to serving as the faculty

advisor of the Graduate Economics

Club.

[9]

Some colleagues thought his views

outdated and not in tune with the then-

fashionable Keynesianism; others resented

his criticisms, particularly of their failure to

offer an assistant professorship to Paul

Samuelson, but recanted when they

thought him likely to accept a position

at Yale University.

[10]

This period of his life

was characterized by hard work but

comparatively little recognition of his

massive 2-volume book Business

Cycles. However, the Schumpeters

persevered, and in 1942 published what

became the most popular of all his

works, Capitalism, Socialism and

Democracy, reprinted many times and in

many languages in the following decades,

as well as cited thousands of times.

[11]

Although Schumpeter encouraged some

young mathematical economists and was

even the president of the Econometric

Society (194041), Schumpeter was not a

mathematician, but rather an economist,

and tried instead to integrate history

and sociological understanding into his

economic theories. Some argue that

Schumpeter's ideas on business

cyclesand economic development could not

be captured in the mathematics of his day

they need the language of non-

linear dynamical systems to be partially

formalized.

[citation needed]

Schumpeter claimed that he had set himself

three goals in life: to be the greatest

economist in the world, to be the best

horseman in all of Austria and the greatest

lover in all ofVienna. He said he had

reached two of his goals, but he never said

which two,

[12][13]

although he is reported to

have said that there were too many fine

horsemen in Austria for him to succeed in

all his aspirations.

[14]

Schumpeter died in his home in Taconic,

Connecticut, at the age of 66, on the night

of 7 January 1950.

[15]

He was married three times.

[16]

His first wife

was Gladys Ricarde Seaver, an

Englishwoman nearly 12 years his senior

(married 1907, separated 1913, divorced

1925). His best man at his wedding was his

friend and Austrian jurist Hans Kelsen. His

second was Anna Reisinger, twenty years

his junior and the daughter of the concierge

of the apartment where he grew up. They

married in 1925, but within a year of their

marriage, she died in childbirth. The loss of

his wife and newborn son came only weeks

after Schumpeter's mother had died. In

1937, Schumpeter married the American

economic historian Elizabeth Boody, who

helped him to popularize his work and

edited what became their magnum opus,

the posthumously published History of

Economic Analysis.

[17]

Central contributions[edit]

Influences[edit]

The source of Joseph Schumpeter's

dynamic, change-oriented, and innovation-

based economics was the Historical School

of economics. Although his writings could

be critical of the School, Schumpeter's work

on the role of innovation

and entrepreneurship can be seen as a

continuation of ideas originated by the

Historical School, especially the work

of Gustav von Schmoller and Werner

Sombart.

[18][19]

Evolutionary economics[edit]

Main article: Evolutionary economics

According to Christopher Freeman (2009),

a scholar who devoted much time

researching Schumpeter's work: "the

central point of his whole life work [is]: that

capitalism can only be understood as an

evolutionary process of continuous

innovation and 'creative destruction' [...]."

[20]

History of Economic Analysis[edit]

Schumpeter's scholarship is apparent in his

posthumous History of Economic Analysis,

although some of his judgments

seem idiosyncratic and sometimes cavalier.

For instance, Schumpeter thought that the

greatest 18th century economist

was Turgot, not Adam Smith, as many

consider, and he considered Lon

Walras to be the "greatest of all

economists", beside whom other

economists' theories were "like inadequate

attempts to catch some particular aspects

of Walrasian truth".

[21]

Schumpeter

criticized John Maynard Keynes andDavid

Ricardo for the "Ricardian vice." According

to Schumpeter, Ricardo and Keynes

reasoned in terms of abstract models,

where they would freeze all but a few

variables. Then they could argue that one

caused the other in a

simple monotonic fashion. This led to the

belief that one could easily deduce policy

conclusions directly from a highly abstract

theoretical model.

In this book, Joseph Schumpeter

recognized the implication of a gold

monetary standard compared to a fiat

monetary standard. In History of Economic

Analysis, Schumpeter stated the following:

"An 'automatic' gold currency is part and

parcel of a laissez-faire and free-

trade economy. It links every nation's

money rates and price levels with the

money-rates and price levels of all the other

nations that are 'on gold.' It is extremely

sensitive to government expenditure and

even to attitudes or policies that do not

involve expenditure directly, for example, to

foreign policy, to certain policies of taxation,

and, in general, to precisely all those

policies that violate the principles of

[classical] liberalism. This is the reason why

gold is so unpopular now and also why it

was so popular in a bourgeois era.

[22]

Business cycles[edit]

Schumpeter's relationships with the ideas of

other economists were quite complex in his

most important contributions to economic

analysis the theory of business

cycles and development. Following neither

Walras nor Keynes, Schumpeter starts

in The Theory of Economic

Development

[23]

with a treatise of circular

flow which, excluding any innovations and

innovative activities, leads to a stationary

state. The stationary state is, according to

Schumpeter, described by Walrasian

equilibrium. The hero of his story is

the entrepreneur.

T

h

e

e

nt

re

pr

e

n

e

ur

di

sturbs this equilibrium and is the prime

cause of economic development, which

proceeds in cyclic fashion along several

time scales. In fashioning this theory

Proposed Economic Waves

Cycle/Wave Name Period

Kitchin inventory 35

Juglar fixed investment 711

Kuznets infrastructural investment 1525

Kondratiev wave 4560

Pork cycle

This box:

view

talk

edit

connecting innovations, cycles, and

development, Schumpeter kept alive the

Russian Nikolai Kondratiev's ideas on 50-

year cycles, Kondratiev waves.

Schumpeter suggested a model in which

the four main cycles, Kondratiev (54 years),

Kuznets (18 years), Juglar (9 years)

and Kitchin(about 4 years) can be added

together to form a composite waveform.

Actually there was considerable

professional rivalry between Schumpeter

and Kuznets. The wave form suggested

here did not include the Kuznets

Cycle simply because Schumpeter did not

recognize it as a valid cycle

[clarification needed]

. See

"business cycle" for further information. A

Kondratiev wave could consist of three

lower degree Kuznets waves.

[24]

Each

Kuznets wave could, itself, be made up of

two Juglar waves. Similarly two (or three)

Kitchin waves could form a higher degree

Juglar wave. If each of these were in

phase, more importantly if the downward

arc of each was simultaneous so that

the nadir of each was coincident it would

explain disastrous slumps and consequent

depressions. As far as the segmentation of

the Kondratiev Wave, Schumpeter never

proposed such a fixed model. He saw these

cycles varying in time although in a tight

time frame by coincidence and for each to

serve a specific purpose.

Keynesianism[edit]

In Schumpeter's theory, Walrasian

equilibrium is not adequate to capture the

key mechanisms of economic development.

Schumpeter also thought that the institution

enabling the entrepreneur to purchase the

resources needed to realize his or her

vision was a well-

developed capitalist financial system,

including a whole range of institutions for

granting credit. One could divide

economists among (1) those who

emphasized "real" analysis and regarded

money as merely a "veil" and (2) those who

thought monetary institutions are important

and money could be a separate driving

force. Both Schumpeter and Keynes were

among the latter.

[citation needed]

Capitalism's demise[edit]

Schumpeter's most popular book in English

is probably Capitalism, Socialism and

Democracy. This book opens with a

treatment of Karl Marx. While he is

sympathetic to Marx's theory that capitalism

will collapse and will be replaced

by socialism, Schumpeter concludes that

this will not come about in the way Marx

predicted. While Marx predicted that

capitalism would be overthrown by a

proletarian violent revolution, which

historically actually happened in the least

capitalist economic countries, Schumpeter

instead believed that the capitalist system

would collapse as a result of an internal

conflict that bolstered hostilities among

itself. To describe it he borrowed the phrase

"creative destruction", and made it famous

by using it to describe a process in which

the old ways of doing things

are endogenously destroyed and replaced

by new ways.

Schumpeter's theory is that the success of

capitalism will lead to a form

of corporatism and a fostering of values

hostile to capitalism, especially

among intellectuals. The intellectual and

social climate needed to

allow entrepreneurship to thrive will not

exist in advanced capitalism; it will be

replaced by "laborism" in some form. He

points out that intellectuals, whose very

profession relies on antagonism toward the

capitalist structure, are automatically

inclined to have a negative outlook toward it

even while relying upon it for prestige.

There will not be a revolution, but merely

instead a trend in parliaments to elect social

democratic parties of one stripe or another.

He argued that the collapse of capitalism

from within will come about if democratic

majorities vote for restrictions upon

entrepreneurship that will burden and

destroy the capitalist structure. He also

emphasized non-political, evolutionary

processes in society where "liberal

capitalism" was evolving because of the

growth of workers' self-

management, industrial democracy and

regulatory institutions.

[25]

Schumpeter emphasizes throughout this

book that he is analyzing trends, not

engaging in political advocacy. In his vision,

the intellectual class will play an important

role in capitalism's evolution. The term

"intellectuals" denotes a class of persons in

a position to develop critiques of societal

matters for which they are not directly

responsible and able to stand up for the

interests of strata to which they themselves

do not belong. One of the great advantages

of capitalism, he argues, is that as

compared with pre-capitalist periods, when

education was a privilege of the few, more

and more people acquire (higher)

education. The availability of fulfilling work

is, however, limited, and this lack, coupled

with the experience of unemployment,

produces discontent. The intellectual class

is then able to organize protest and develop

critical ideas.

Democratic theory[edit]

In the same book, Schumpeter expounded

a theory of democracy which sought to

challenge what he called the "classical

doctrine". He disputed the idea that

democracy was a process by which the

electorate identified the common good, and

politicians carried this out for them. He

argued this was unrealistic, and that

people's ignorance and superficiality meant

that in fact they were largely manipulated

by politicians, who set the agenda. This

made a 'rule by the people' concept both

unlikely and undesirable. Instead he

advocated a minimalist model, much

influenced by Max Weber, whereby

democracy is the mechanism for

competition between leaders, much like a

market structure. Although periodic votes

by the general public legitimize

governments and keep them accountable,

the policy program is very much seen as

their own and not that of the people, and

the participatory role for individuals is

usually severely limited.

Entrepreneurship[edit]

The research of entrepreneurship owes

much to his contributions. He was probably

the first scholar to develop theories in this

field. His fundamental theories are often

referred to as Mark I and Mark II. In the

first, Schumpeter argued that the innovation

and technological change of a nation come

from the entrepreneurs, or wild spirits. He

coined the wordUnternehmergeist, German

for entrepreneur-spirit, and asserted that "...

the doing of new things or the doing of

things that are already being done in a new

way"

[26]

stemmed directly from the efforts of

entrepreneurs.

Mark II was developed when Schumpeter

was a professor at Harvard. Many social

economists and popular authors of the day

argued that the net effect of the existence

of large businesses was negative on the

standard of living for the average person of

the day. Contrary to this prevailing opinion,

he asserted that the agents that drive

innovation and the economy are large

companies which have the resources and

capital to invest in research and

development to create new products and

services and to deliver them to individuals

less expensivelythus raising their

standard of living. In one of his seminal

works, "Capitalism, Socialism and

Democracy", Schumpeter wrote:

As soon as we go into details and inquire

into the individual items in which progress

was most conspicuous, the trail leads not to

the doors of those firms that work under

conditions of comparatively free competition

but precisely to the door of the large

concerns--which, as in the case of

agricultural machinery, also account for

much of the progress in the competitive

sector--and a shocking suspicion dawns

upon us that big business may have had

more to do with creating that standard of life

than with keeping it down.

[27]

Mark I and Mark II arguments are

considered complementary today.

Cycles and long wave theory[edit]

[28]

[29]

Schumpeter, foremost and most

influential articulator of the opposite view -

that long cycles are caused by, and are an

incident of the innovation process. Indeed,

Kondratiev's ideas were first bought to

attention of English-speaking economist

through Schumpeter's treatise on business

cycles, in spite of the fact that Schumpeter

urged a causality that was sharply in

contrast with Kondratiev's moreover, it is

the Schumpeterian variant of long-cycles

hypothesis, stressing the initiating role of

innovations, that commands the widest

attention today. This is a shame as

Kondratiev was fusing important elements

that Schumpeter often missed.

[30]

In

Schumpeter's view, technological

innovation is at the center of both cyclical

instability and economic growth, with the

direction of causality moving clearly from

fluctuations in innovation to fluctuation in

investment and from that to cycles in

economics growth, moreover, Schumpeter

sees innovations as clustering around

certain points in time periods that he refers

to as "neighborhoods of equilibrium", when

entrepreneurial perception of risk and

returns warranted innovative commitments.

These clustering, in turn lead to long cycles

by generating periods of acceleration in

aggregate growth rate.

[28]

[29]

[31]

Schumpeter,

foremost and most influential articulator of

the opposite view - that long cycles are

caused by, and are an incident of the

innovation process. Indeed, Kondratiev's

ideas were first bought to attention of

English-speaking economist through

Schumpeter's treatise on business cycles,

in spite of the fact that Schumpeter urged a

causality that was sharply in contrast with

Kondratiev's. Moreover, it is the

Schumpeterian variant of long-cycles

hypothesis, stressing the initiating role of

innovations, that commands the widest

attention today. This is a shame as

Kondratiev was fusing important elements

that Schumpeter often missed.

[30]

In

Schumpeter's view, technological

innovation is at the center of both cyclical

instability and economic growth, with the

direction of causality moving clearly from

fluctuations in innovation to fluctuation in

investment and from that to cycles in

economics growth, moreover, Schumpeter

sees innovations as clustering around

certain points in time periods that he refers

to as "neighborhoods of equilibrium", when

entrepreneurial perception of risk and

returns warranted innovative commitments.

These clustering, in turn lead to long cycles

by generating periods of acceleration in

aggregate growth rate.

[32]

Technological

view of changes is at the root of the long

cycle needs to demonstrate: Change in the

rate of innovation governs changes in the

rate of new investments and that combines

impact of innovation clusters takes the form

of fluctuation in aggregate output or

employment. The process of technological

innovation involves extremely complex

relation among a set of key variables-

inventions, innovations, diffusion paths and

investment activities. The impact of

technological innovation on aggregate

output is mediated through a succession of

relationship that have yet to be explored

systematically in context of long wave. New

inventions are typically very primitive at

their birth. Their performance usually poor,

compared to existing technologies as well

as their future performance. moreover, the

cost of production, at this initial stage, is

likely to be high- indeed, in some cases a

production technology may simply not yet

exist, as is often observes in major

chemical inventions, pharma inventions etc.

the speed with which inventions are

transformed into innovations, and

consequently diffused will depend upon

actual and expected trajectory of

performance improvement and cost

reduction.

[33]

Technological view of changes is at the root

of the long cycle needs to demonstrate:

Change in the rate of innovation governs

changes in the rate of new investments and

that combines impact of innovation clusters

takes the form of fluctuation in aggregate

output or employment. The process of

technological innovation involves extremely

complex relation among a set of key

variables- inventions, innovations, diffusion

paths and investment activities. The impact

of technological innovation on aggregate

output is mediated through a succession of

relationship that have yet to be explored

systematically in context of long wave. New

inventions are typically very primitive at

their birth. Their performance usually poor,

compared to existing technologies as well

as their future performance. moreover, the

cost of production, at this initial stage, is

likely to be high- indeed, in some cases a

production technology may simply not yet

exist, as is often observes in major

chemical inventions, pharma inventions etc.

the speed with which inventions are

transformed into innovations, and

consequently diffused will depend upon

actual and expected trajectory of

performance improvement and cost

reduction.

[33]

Innovation[edit]

Schumpeter identified innovation as the

critical dimension of economic

change.

[34]

He argued that economic change

revolves around innovation, entrepreneurial

activities, and market power. He sought to

prove that innovation-originated market

power could provide better results than the

invisible hand and price competition. He

argues that technological innovation often

creates temporary monopolies, allowing

abnormal profits that would soon be

competed away by rivals and imitators. He

said that these temporary monopolies were

necessary to provide the incentive

necessary for firms to develop new

products and processes.

[34]

Legacy[edit]

For some time after his death,

Schumpeter's views were most influential

among various heterodox economists,

especially European, who were interested

in industrial organization,evolutionary

theory, and economic development, and

who tended to be on the other end of the

political spectrum from Schumpeter and

were also often influenced by Keynes, Karl

Marx, and Thorstein Veblen. Robert

Heilbroner was one of Schumpeter's most

renowned pupils, who wrote extensively

about him in The Worldly Philosophers. In

the journal Monthly Review John Bellamy

Foster wrote of that journal's founder Paul

Sweezy, one of the leading Marxist

economists in the United States and a

graduate assistant of Schumpeter's at

Harvard, that Schumpeter "played a

formative role in his development as a

thinker".

[35]

Other outstanding students of

Schumpeter's include the

economists Nicholas Georgescu-

Roegen and Hyman Minsky and former

chairman of the Federal Reserve, Alan

Greenspan.

[36]

Future Nobel

Laureate Robert Solow was his student at

Harvard, and he expanded on

Schumpeter's theory.

[37]

Today, Schumpeter has a following outside

of standard textbook economics, in areas

such as in economic policy, management

studies, industrial policy, and the study

of innovation. Schumpeter was probably the

first scholar to develop theories

about entrepreneurship. For instance,

the European Union's innovation program,

and its main development plan, theLisbon

Strategy, are influenced by Schumpeter.

The International Joseph A. Schumpeter

Society awards the Schumpeter Prize.

The Schumpeter School of Business and

Economics opened in October 2008 at

the University of Wuppertal. According to

University President Professor Lambert T.

Koch, "Schumpeter will not only be the

name of the Faculty of Management and

Economics, but this is also a research and

teaching programme related to Joseph A.

Schumpeter."

[38]

On 17 September 2009, The

Economist inaugurated a column on

business and management named

"Schumpeter."

[39]

The publication has a

history of naming columns after significant

figures or symbols in the covered field,

including naming its British affairs column

after former editor Walter Bagehot and its

European affairs column

after Charlemagne. The initial Schumpeter

column praised him as a "champion of

innovation and entrepreneurship" whose

writing showed an understanding of the

benefits and dangers of business that

proved to be far ahead of its time.

[40]

Major works[edit]

"ber die mathematische Methode der

theoretischen konomie", 1906, ZfVSV.

"Das Rentenprinzip in der Verteilungslehre",

1907, Schmollers Jahrbuch.

Wesen und Hauptinhalt der theoretischen

Nationalkonomie (transl. The Nature and

Essence of Theoretical Economics), 1908.

"Methodological Individualism", 1908,

[41]

"On the Concept of Social Value",

1909, QJE.

Wie studiert man Sozialwissenschaft, 1910

(transl. by J.Z. Muller, "How to Study Social

Science", Society, 2003).

"Marie Esprit Leon Walras", 1910, ZfVSV.

"ber das Wesen der Wirtschaftskrisen",

1910, ZfVSV.

Theorie der wirtschaftlichen

Entwicklung (transl. 1934, The Theory of

Economic Development: An inquiry into

profits, capital, credit, interest and the

business cycle) 1911.

Economic Doctrine and Method: An

historical sketch, 1914.

[42]

"Das wissenschaftliche Lebenswerk Eugen

von Bhm-Bawerks", 1914, ZfVSV.

Vergangenkeit und Zukunft der

Sozialwissenschaft, 1915.

The Crisis of the Tax State, 1918.

"The Sociology of Imperialisms",

1919, Archiv fr Sozialwissenschaft und

Sozialpolitik

[43]

"Max Weber's Work", 1920, Der

sterreichische Volkswirt.

"Carl Menger", 1921, ZfVS.

"The Explanation of the Business Cycle",

1927, Economica.

"Social Classes in an Ethnically

Homogeneous Environment", 1927, Archiv

fr Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik.

[43]

"The Instability of Capitalism", 1928, EJ.

Das deutsche Finanzproblem, 1928.

"Mitchell's Business Cycles", 1930, QJE.

"The Present World Depression: A tentative

diagnosis", 1931, AER.

"The Common Sense of Econometrics",

1933, Econometrica.

"Depressions: Can we learn from past

experience?", 1934, in Economics of the

Recovery Program

"The Nature and Necessity of a Price

System", 1934, Economic Reconstruction.

"Review of Robinson's Economics of

Imperfect Competition", 1934, JPE.

"The Analysis of Economic Change",

1935, REStat.

"Professor Taussig on Wages and Capital",

1936, Explorations in Economics.

"Review of Keynes's General Theory",

1936, JASA.

Business Cycles: A theoretical, historical and

statistical analysis of the Capitalist process,

1939.

"The Influence of Protective Tariffs on the

Industrial Development of the United States",

1940, Proceedings of AAPS.

"Alfred Marshall's Principles: A semi-

centennial appraisal", 1941, AER.

"Frank William Taussig", 1941, QJE.

Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, 1942.

"Capitalism in the Postwar World",

1943, Postwar Economic Problems.

"John Maynard Keynes", 1946, AER.

"The Future of Private Enterprise in the Face

of Modern Socialistic Tendencies",

1946, Comment sauvegarder l'entreprise

prive

Rudimentary Mathematics for Economists

and Statisticians, with W.L .Crum, 1946.

"Capitalism", 1946, Encyclopdia

Britannica.

"The Decade of the Twenties", 1946, AER.

"The Creative Response in Economic

History", 1947, JEH.

"Theoretical Problems of Economic Growth",

1947, JEH.

"Irving Fisher's Econometrics",

1948, Econometrica.

"There is Still Time to Stop Inflation",

1948, Nation's Business.

"Science and Ideology", 1949, AER.

"Vilfredo Pareto", 1949, QJE.

"Economic Theory and Entrepreneurial

History", 1949, Change and the

Entrepreneur.

"The Communist Manifesto in Sociology and

Economics", 1949, JPE.

"English Economists and the State-Managed

Economy", 1949, JPE.

"The Historical Approach to the Analysis of

Business Cycles", 1949, NBER Conference

on Business Cycle Research.

"Wesley Clair Mitchell", 1950, QJE.

"March into Socialism", 1950, AER.

Ten Great Economists: From Marx to

Keynes, 1951.

[44]

Imperialism and Social Classes, 1951

(reprints of 1919, 1927)

Essays on Economic Topics, 1951.

"Review of the Troops", 1951, QJE.

History of Economic Analysis, (published

posthumously, ed. Elisabeth Boody

Schumpeter), 1954.

"American Institutions and Economic

Progress", 1983, Zeitschrift fur die gesamte

Staatswissenschaft

"The Meaning of Rationality in the Social

Sciences", 1984, Zeitschrift fur die gesamte

Staatswissenschaft

"Money and Currency", 1991, Social

Research.

Economics and Sociology of Capitalism,

1991.

Treatise on Money (Complete translation

of Das Wesen des Geldes, Vandenhoeck &

Ruprecht, 1970), WordBridge Publishing,

2014.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Joseph SchumpeterDocumento11 pagineJoseph Schumpeterafjkjchhghgfbf100% (1)

- Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy - SchumpeterDa EverandCapitalism, Socialism and Democracy - SchumpeterNessuna valutazione finora

- Weber, Schumpeter and Knight On Entrepreneurship and Economic DevelopmentDocumento23 pagineWeber, Schumpeter and Knight On Entrepreneurship and Economic DevelopmentjamilkhannNessuna valutazione finora

- Capitalist Development, Innovations, Business Cycles and Unemployment: Joseph Alois Schumpeter and Emil Hans LedererDocumento16 pagineCapitalist Development, Innovations, Business Cycles and Unemployment: Joseph Alois Schumpeter and Emil Hans LedererKaren DayanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Knight Schumpeter WeberDocumento24 pagineKnight Schumpeter Weberpalacaguina100% (1)

- The Fortunes of Liberalism: Essays on Austrian Economics and the Ideal of FreedomDa EverandThe Fortunes of Liberalism: Essays on Austrian Economics and the Ideal of FreedomNessuna valutazione finora

- New Perspectives On Political Economy: ISSN 1801-0938Documento18 pagineNew Perspectives On Political Economy: ISSN 1801-0938Edgar ORNessuna valutazione finora

- Hayek and FriedmanDocumento5 pagineHayek and FriedmanRicabele MaligsaNessuna valutazione finora

- Gustav Von Schmoller - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocumento4 pagineGustav Von Schmoller - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaClaviusNessuna valutazione finora

- Essential Joseph SchumpeterDocumento68 pagineEssential Joseph Schumpeteryassinaziz509Nessuna valutazione finora

- David RicardoDocumento22 pagineDavid RicardoY D Amon GanzonNessuna valutazione finora

- Joseph SchumpeterDocumento3 pagineJoseph SchumpeterChris Hull100% (2)

- Who Is FA HayekDocumento4 pagineWho Is FA HayekstarsaiNessuna valutazione finora

- Werner Sombart's The Jews and Modern CapitalismDocumento28 pagineWerner Sombart's The Jews and Modern CapitalismFauzan RasipNessuna valutazione finora

- This Content Downloaded From 188.29.165.99 On Tue, 21 Jul 2020 01:25:34 UTCDocumento29 pagineThis Content Downloaded From 188.29.165.99 On Tue, 21 Jul 2020 01:25:34 UTCLuqmanSudradjatNessuna valutazione finora

- Thomas K. Mccraw, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 719 Pages, $35Documento8 pagineThomas K. Mccraw, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 719 Pages, $35dusu1986Nessuna valutazione finora

- Institutional Thought in Germany: January 2000Documento32 pagineInstitutional Thought in Germany: January 2000Gabriele CiampiniNessuna valutazione finora

- Commission 2Documento33 pagineCommission 2Marina VerbumNessuna valutazione finora

- On Freedom and Free Enterprise Essays in Honor of Ludwig Von MisesDocumento346 pagineOn Freedom and Free Enterprise Essays in Honor of Ludwig Von Miseszval345Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ikeda 5001Documento17 pagineIkeda 5001Spin FotonioNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 1Documento6 pagineChapter 1Solenoid LazarusNessuna valutazione finora

- Murray RothbardDocumento13 pagineMurray Rothbardmises55Nessuna valutazione finora

- Hayek ArticleDocumento13 pagineHayek Articletóth_ilona_2Nessuna valutazione finora

- Hsitory of Thoughts Historical Critics of Neoclassical EconomicsDocumento9 pagineHsitory of Thoughts Historical Critics of Neoclassical EconomicsGörkem AydınNessuna valutazione finora

- Adam SmithprojectDocumento6 pagineAdam SmithprojectJhaLazaroNessuna valutazione finora

- Wilhelm Röpke, John Maynard Keynes, and The Problem of InflationDocumento14 pagineWilhelm Röpke, John Maynard Keynes, and The Problem of InflationVirgilio de CarvalhoNessuna valutazione finora

- Leube 2002 - On Menger, Austrian Economics, and The Use of General EquilibriumDocumento21 pagineLeube 2002 - On Menger, Austrian Economics, and The Use of General EquilibriumJumbo ZimmyNessuna valutazione finora

- The Evolution of EconomicsDocumento4 pagineThe Evolution of EconomicsShena Mae AlicanteNessuna valutazione finora

- Ludwig Von MisesDocumento5 pagineLudwig Von MisesteoNessuna valutazione finora

- Austrian Economic School of ThoughtDocumento6 pagineAustrian Economic School of ThoughtfahmisallehNessuna valutazione finora

- John Maynard KeynesDocumento5 pagineJohn Maynard KeynesŚáńtőśh MőkáśhíNessuna valutazione finora

- Essays in European Economic ThoughtDocumento238 pagineEssays in European Economic ThoughtRafael RochaNessuna valutazione finora

- Economics As A ScienceDocumento11 pagineEconomics As A ScienceTeacher anaNessuna valutazione finora

- Economic School of ThoughtsDocumento13 pagineEconomic School of Thoughtspakhi rawatNessuna valutazione finora

- Paul Samuelson - HistoryDocumento7 paginePaul Samuelson - HistoryMigeulCorreiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Paul SamuelsonDocumento13 paginePaul SamuelsonCHINGZU212Nessuna valutazione finora

- " The Great Thinkers": ADAM SMITH (1723-1790)Documento8 pagine" The Great Thinkers": ADAM SMITH (1723-1790)Amor Vinsent AquinoNessuna valutazione finora

- EconomicsDocumento13 pagineEconomicsWoohyun143Nessuna valutazione finora

- Harris, A. L. (1942) - Sombart and German (National) Socialism. The Journal of Political Economy, 805-835.Documento32 pagineHarris, A. L. (1942) - Sombart and German (National) Socialism. The Journal of Political Economy, 805-835.lcr89Nessuna valutazione finora

- Michel Chevalier: Visionary of Modern Europe?: by Michael DroletDocumento13 pagineMichel Chevalier: Visionary of Modern Europe?: by Michael DroletscribsinNessuna valutazione finora

- Joseph SchumpeterDocumento1 paginaJoseph SchumpeterJinjunNessuna valutazione finora

- Josef Steindl and Capitalist StagnationDocumento19 pagineJosef Steindl and Capitalist StagnationMaria Aparecida Rosa VargasNessuna valutazione finora

- Blue 14Documento5 pagineBlue 14R-jay Del Finado ValentinoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Essential Hayek by Prof. Donald BoudreauxDocumento93 pagineThe Essential Hayek by Prof. Donald Boudreauxbhweingarten80% (5)

- Qjae14 1 6Documento42 pagineQjae14 1 6Jeff RobinsonNessuna valutazione finora

- Great EconomistsDocumento14 pagineGreat EconomistsИринаNessuna valutazione finora

- WEHLER, Hans-Ulrich - Bismarck's Imperialism 1862-1890 PDFDocumento37 pagineWEHLER, Hans-Ulrich - Bismarck's Imperialism 1862-1890 PDFdudcr100% (1)

- 15 Great Austrian EconomistsDocumento273 pagine15 Great Austrian EconomistsBruno GarschagenNessuna valutazione finora

- Writing The History of CapitalismDocumento18 pagineWriting The History of CapitalismenlacesbostonNessuna valutazione finora

- Compaso2012 32 Croitoru PDFDocumento12 pagineCompaso2012 32 Croitoru PDFRenz SolatreNessuna valutazione finora

- Kondratiev Hope 1999Documento39 pagineKondratiev Hope 1999sldvxzlNessuna valutazione finora

- MacroDocumento8 pagineMacrosreejasreeNessuna valutazione finora

- APHETDocumento563 pagineAPHETJacobsen Richard100% (1)

- Tengreateconomists SchumpeterDocumento319 pagineTengreateconomists Schumpeterdeathslayer112Nessuna valutazione finora

- Samuel Gregg - Wilhelm Röpke's Political EconomyDocumento225 pagineSamuel Gregg - Wilhelm Röpke's Political EconomyJacques Ripper100% (2)

- Economic TheoriesDocumento4 pagineEconomic TheoriesGlaiza AdelleyNessuna valutazione finora

- Claire Angela P. Almazan: ObjectiveDocumento2 pagineClaire Angela P. Almazan: ObjectiveAlly GelayNessuna valutazione finora

- Cathlyn Nicole I. Lin: ObjectiveDocumento2 pagineCathlyn Nicole I. Lin: ObjectiveAlly GelayNessuna valutazione finora

- Environmental Impacts Worksheet - Teacher NotesDocumento31 pagineEnvironmental Impacts Worksheet - Teacher NotesAlly GelayNessuna valutazione finora

- Elements of A Short StoryDocumento4 pagineElements of A Short Storykristofer_go18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Predicting OutcomesDocumento3 paginePredicting OutcomesAlly GelayNessuna valutazione finora

- RizalDocumento33 pagineRizalSherly PabellanoNessuna valutazione finora

- HistoryDocumento4 pagineHistoryAlly GelayNessuna valutazione finora

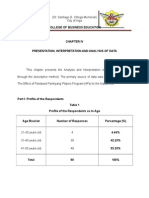

- Chapter IVDocumento18 pagineChapter IVAlly GelayNessuna valutazione finora

- Communitychange FinalDocumento548 pagineCommunitychange FinalAndreiChertes0% (1)

- 'Alamat NG TangaDocumento28 pagine'Alamat NG TangaAlly GelayNessuna valutazione finora

- 10 1 1 419 2211Documento116 pagine10 1 1 419 2211Ally GelayNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Policy Primarily Refers To Guidelines, Principles, Legislation and Activities That Affect The LivingDocumento2 pagineSocial Policy Primarily Refers To Guidelines, Principles, Legislation and Activities That Affect The LivingAlly GelayNessuna valutazione finora

- Ang Totoong "SORRY", Walang Kasunod Na "KASI".: Pinoy QuotesDocumento47 pagineAng Totoong "SORRY", Walang Kasunod Na "KASI".: Pinoy QuotesAlly GelayNessuna valutazione finora

- Milton Snavely HersheyDocumento10 pagineMilton Snavely HersheyAlly GelayNessuna valutazione finora

- Economic GrowthDocumento20 pagineEconomic GrowthAlly GelayNessuna valutazione finora

- Liquidity Risk Management Framework For NBFCS: Study NotesDocumento5 pagineLiquidity Risk Management Framework For NBFCS: Study NotesDipu PiscisNessuna valutazione finora

- Levi Strass and Co v. Papikan Enterprises Trademark MSJDocumento12 pagineLevi Strass and Co v. Papikan Enterprises Trademark MSJNorthern District of California BlogNessuna valutazione finora

- Outgoing Global Volunteer: OG V BramantyaDocumento12 pagineOutgoing Global Volunteer: OG V BramantyaPutri Nida FarihahNessuna valutazione finora

- Morton/Boyer HyposubjectsDocumento96 pagineMorton/Boyer HyposubjectsBen ZuckerNessuna valutazione finora

- Ryterna Modul Architectural Challenge 2021Documento11 pagineRyterna Modul Architectural Challenge 2021Pham QuangdieuNessuna valutazione finora

- Barnacus: City in Peril: BackgroundDocumento11 pagineBarnacus: City in Peril: BackgroundEtienne LNessuna valutazione finora

- Bagabag National High School Instructional Modules in FABM 1Documento2 pagineBagabag National High School Instructional Modules in FABM 1marissa casareno almueteNessuna valutazione finora

- Revised Compendium FOR PERSONAL INJURY AWARDS 2018 Revised Compendium FOR PERSONAL INJURY AWARDS 2018Documento52 pagineRevised Compendium FOR PERSONAL INJURY AWARDS 2018 Revised Compendium FOR PERSONAL INJURY AWARDS 2018LavernyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Compiled LR PDFDocumento13 pagineCompiled LR PDFFrh RzmnNessuna valutazione finora

- Kalmar Care For Material Handling, EN PDFDocumento9 pagineKalmar Care For Material Handling, EN PDFAki MattilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Computer Science and Engineering: Seminar Report On Mass Media byDocumento17 pagineComputer Science and Engineering: Seminar Report On Mass Media byJohnny ThomasNessuna valutazione finora

- Taqwa (Pıety) Beıng Conscıous of Maıntaınıng Allah's PleasureDocumento1 paginaTaqwa (Pıety) Beıng Conscıous of Maıntaınıng Allah's PleasuretunaNessuna valutazione finora

- C.V ZeeshanDocumento1 paginaC.V ZeeshanZeeshan ArshadNessuna valutazione finora

- ACCT 403 Cost AccountingDocumento7 pagineACCT 403 Cost AccountingMary AmoNessuna valutazione finora

- Grupo NovEnergia, El Referente Internacional de Energía Renovable Dirigido Por Albert Mitjà Sarvisé - Dec2012Documento23 pagineGrupo NovEnergia, El Referente Internacional de Energía Renovable Dirigido Por Albert Mitjà Sarvisé - Dec2012IsabelNessuna valutazione finora

- SLRC InstPage Paper IIIDocumento5 pagineSLRC InstPage Paper IIIgoviNessuna valutazione finora

- Marilena Murariu, DESPRE ELENA ÎN GENERAL at Galeria SimezaDocumento19 pagineMarilena Murariu, DESPRE ELENA ÎN GENERAL at Galeria SimezaModernismNessuna valutazione finora

- User Guide: How To Register & Verify Your Free Paxum Personal AccountDocumento17 pagineUser Guide: How To Register & Verify Your Free Paxum Personal AccountJose Manuel Piña BarriosNessuna valutazione finora

- Radical Feminism Enters The 21st Century - Radfem HubDocumento53 pagineRadical Feminism Enters The 21st Century - Radfem HubFidelbogen CfNessuna valutazione finora

- Obsa Ahmed Research 2013Documento55 pagineObsa Ahmed Research 2013Ebsa AdemeNessuna valutazione finora

- Standard Oil Co. of New York vs. Lopez CasteloDocumento1 paginaStandard Oil Co. of New York vs. Lopez CasteloRic Sayson100% (1)

- Elizabeth Stevens ResumeDocumento3 pagineElizabeth Stevens Resumeapi-296217953Nessuna valutazione finora

- Internship ReportDocumento44 pagineInternship ReportRAihan AhmedNessuna valutazione finora

- CCOB 021 and CCOC 021 Module Outline For 2022Documento5 pagineCCOB 021 and CCOC 021 Module Outline For 2022Matodzi ArehoneNessuna valutazione finora

- 3.19 Passive VoiceDocumento10 pagine3.19 Passive VoiceRetno RistianiNessuna valutazione finora

- Company Loan PolicyDocumento2 pagineCompany Loan PolicyKaleem60% (5)

- IJN Minekaze, Kamikaze and Mutsuki Class DestroyersDocumento11 pagineIJN Minekaze, Kamikaze and Mutsuki Class DestroyersPeterD'Rock WithJason D'Argonaut100% (2)

- Anouk - Hotel New YorkDocumento46 pagineAnouk - Hotel New YorkRossi Tan100% (2)

- DSSB ClerkDocumento4 pagineDSSB Clerkjfeb40563Nessuna valutazione finora

- Animal AkanDocumento96 pagineAnimal AkanSah Ara SAnkh Sanu-tNessuna valutazione finora