Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Analyses: Can An Inheritance Evade An Insolvent Communal Estate?

Caricato da

Allan Sabz NcubeTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Analyses: Can An Inheritance Evade An Insolvent Communal Estate?

Caricato da

Allan Sabz NcubeCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Analyses

Can an Inheritance Evade an Insolvent

Communal Estate?

ROGER G EVANS

University of South Africa

Introduction

Prudent testators take the necessary measures in their testamentary

instruments to safeguard their assets for the generations that follow. It is

common for testators to exclude a bequest from a communal marital

estate or an heir's insolvent estate. But some testators, or presumably

their estate administrators, do so more successfully than others. So, for

example, many courts have considered whether an inheritance coming the

way of an heir shortly before, or during sequestration, should be included

or excluded from the heir's insolvent estate, or from the communal

insolvent estate of an heir. At first blush, the Matrimonial Property Act

88 of 1984, other legislative provisions, and the common law create the

impression that spouses married in community of property may acquire

property that is separate from the communal estate, and so also out of

the reach of the creditors of the insolvent communal estate. But the

impression that such property may be placed beyond the reach of

creditors is false. Recently, in Du Plessis v Pienaar NO & others 2003 (1)

SA 671 (SCA), the Supreme Court of Appeal has confirmed that this is

not possible. Finding clarity has not been easy. The uncertainty that

enveloped the legal principles relating to this field of law left the courts

and academics sometimes groping blindly for judicial precedent or

common-law authority to support their proposed solutions.

That this field of law proved to be difficult for jurists was confirmed by

Lee and Honore (Family, Things and Succession 2 ed by HJ Erasmus,

CG van der Merwe & AH van Wyk (1983) para 82n3):

`The precise nature and implications of this community of debts are matters of some

difficulty and uncertainty in our present law. . . . This is due to the fact that our Courts

(mostly unconsciously) vacillate between two entirely different approaches. . . . The first

approach treats the spouses as joint debtors. . . . The second approach does not regard

the spouses as joint debtors. . . .'

(For conflicting opinions and decisions, see, amongst others, W de Vos

`Aanspreeklikheid van die Vrou Getroud in Gemeenskap van Goedere vir

Gemeenskapskulde na Ontbinding van die Huwelik' (1954) 27 THRHR

125 at 137; HR Hahlo The South African Law of Husband and Wife 4 ed

228

CAN AN INHERITANCE EVADE AN INSOLVENT COMMUNAL ESTATE?

229

(1975) 226, 5 ed (1985) 166; CJ Nagel & A Boraine `Gevolge van

Sekwestrasie van Gemeenskaplike Boedel op Testamente re Uitgeslote

Bates' (1993) 26 De Jure 457; JC Sonnekus `Insolvensie by Huwelike in

Gemeenskap van Goed' 1986 TSAR 92; JC Sonnekus `Prive Bates en

Sekwestrasie in Huwelik in Gemeenskap van Goed' 1994 TSAR 143;

A van Aswegen `Die Insolvente Gade en die Wet op Huweliksgoedere 88

van 1984' June 1986 De Rebus 273; JP Yeats `Die Algehele Huweliksgemeenskap van Goedere' (1944) 17 THRHR 142 at 162.)

In In re William Dyne's Estate 1885 NLR 43 at 46 and 47, Connor CJ

likewise stated:

`It may not, at first, be easy to see how, in our law, a wife's interest in the community of

goods occasioned by her marriage, becomes vested in the trustee of her husband's

insolvency. . . . The case has occasioned me not a little difficulty, but, on the whole, it

seems to me that we may look upon the sum, now in question, in this light. . .'.

In this analysis I shall consider whether an inheritance may be excluded

from an insolvent joint estate, or how it may evade it. To this end I shall

consider recent case law, and the possibility of the existence of separate

estates of a debtor at the time of, and during, his or her insolvency.

Recent Case Law

Can the `separate property' of a spouse who is married in community

of property be excluded from the insolvent (joint) estate? In Badenhorst v

Bekker NO en andere 1994 (2) SA 155 (N), the court ruled that this was

not possible. In that case a testator bequeathed a substantial amount of

property to his daughter, the applicant, who was married in community

of property. During 1985 the communal estate was sequestrated. In 1989,

the applicant's father drafted a will bequeathing the said property to his

daughter. The testator died in 1992 at a time when the communal estate

of his daughter and her spouse was still under sequestration. A clause in

the will bequeathed the property to the applicant as her separate

property, to be excluded from the community of property and from her

husband' marital power, and immune to, or free from the debts of the

communal estate. The respondents, the trustees of the insolvent

communal estate, claimed the bequeathed property for the benefit of

the insolvent estate. The applicant applied for a declaratory order that

she was entitled to the excluded assets.

McLaren J held (at 159DH) that while it was possible for the testator

to bequeath the assets as the applicant's separate property and to exclude

them from the community of property (see also Erasmus v Erasmus 1942

AD 265; Cuming v Cuming & others 1945 AD 201), it was not possible to

exclude them from the insolvent communal estate (see also, for example,

Vorster v Steyn NO en andere 1981 (2) SA 831 (O)). The status of these

assets, the court found (at 159HI), was governed by the Insolvency Act

24 of 1936. Sequestration of the communal insolvent estate of spouses

results in the insolvency of both spouses (see, for example, De Wet NO v

230

(2003) 15 SA Merc LJ

Jurgens 1970 (3) SA 38 (A)). Accordingly, the court held, inasmuch as

the excluded assets accrued to the applicant after the sequestration of

the joint estate, they were governed by section 20 and in this way vested

in the insolvent joint estate (at 159I, 160D, and 160F). The court pointed

out that the Act contained no provision that pertinently deals with the

excluded assets. Although there are exceptions to the general rule set out

in section 20, the court held that the excluded assets in a joint estate were

not included in these exceptions (at 160AF). The court also ruled that

there was no authority at common law or in any judgment of the courts

that excluded the separate property of a spouse in a communal estate from

the reach of the creditors of the joint estate (at 161B and further). The

judge was of the opinion that the confusion that has occurred amongst

authors and in the courts in respect of the separate assets of spouses with

joint estates vis-a-vis the creditors of such estate, could be ascribed largely

to the failure to enquire whether the relevant spouse is a debtor of the

creditors of the insolvent joint estate (at 171BC). The spouses are codebtors in the communal estate. So the debts of the husband and the wife

in a marriage in community of property are communal debts payable out

of the communal estate (at 172AB; see also Nedbank Ltd v Van Zyl 1990

(2) SA 469 (A) at 476BE; De Wet NO v Jurgens supra at 47DF).

This question in respect of the separate assets of a spouse married in

community of property again came before the courts in Du Plessis v

Pienaar NO & others 2003 (1) SA 671 (SCA). Before considering this

recent judgment of the Supreme Court of Appeal, it is appropriate first to

look at some of the relevant legislative provisions.

The Insolvency Act and the Matrimonial Property Act

By virtue of section 20(1)(a) of the Insolvency Act, the sequestration of

the estate of a debtor divests the insolvent of his or her estate, and vests it,

ultimately, in the trustee. For this purpose, the estate of an insolvent

includes all the property of the debtor at the date of sequestration,

including property in the hands of the sheriff under a writ of attachment,

and property that the insolvent acquires or that may accrue to him or her

during sequestration, except as otherwise provided by section 23

(s 20(2)(a)(b) of the Act). Section 23 states that subject to its provisions

and those of section 24, `all property acquired by an insolvent shall

belong to his estate'. Section 23 then provides for certain property that is

specifically excluded from the insolvent estate.

Under the Matrimonial Property Act, an application for the surrender

of a joint estate must be made by both spouses, and an application for the

sequestration of a joint estate must likewise be made against both spouses

(s 17(4)(a) and (b)). The implication is that both spouses are recognized

as debtors in the insolvent (joint) estate. A consequence of a marriage in

community of property is that the spouses become co-owners of all the

property that either of them has brought into the marriage. In this respect

CAN AN INHERITANCE EVADE AN INSOLVENT COMMUNAL ESTATE?

231

transfer of ownership occurs by operation of law. A further consequence

is that, generally, all property acquired by either spouse during the

marriage in community of property also becomes part of their joint estate

(DSP Cronje & J Heaton South African Family Law (1999) 86). But there

are exceptions to this general rule. The common law, the Matrimonial

Property Act, and other legislation provide for the creation of a `separate

estate' within a joint estate. For example, assets can be excluded from the

joint estate in an antenuptial contract, by a will or deed of donation, or

by a fideicommissum or usufruct. So, for example, the Matrimonial

Property Act contains several exclusions and makes such excluded

property part of a spouse's separate property (see, for example, ss 17(3),

18, and 19). `Separate property' is defined as `property which does not

form part of a joint estate' (s 1).

Du Plessis v Pienaar

The Supreme Court of Appeal recently had the final word as to

whether the `separate property' of spouses married in community of

property is excluded from the insolvent joint estate. In Du Plessis v

Pienaar (supra), the question of separate assets again arose where the

appellant inherited a considerable amount of movable and immovable

property from her father in 1983. The appellant was married in

community of property when the inheritance accrued to her. Her

father, the testator, bequeathed the property to her, subject to a

stipulation, amongst others, that it was to be excluded from the joint

estate of the appellant and her husband, and that it was to be excluded

from `any possible insolvent estate'. In March 2000, the joint estate of the

appellant and her husband was finally sequestrated as a result of her

husband's failed business venture. The trustees (the respondents) claimed

the appellant's separate property for the benefit of the creditors of the

insolvent estate. Following Badenhorst v Bekker NO (supra), Van der

Westhuizen J in the court of first instance dismissed the appellant's

application to prevent the trustees from selling the property for the

benefit of the creditors, and to restore the property to her.

On appeal, the appellant submitted that the debts that had given rise to

the claims against the insolvent estate were debts incurred by the joint

estate and so could be recovered only from the property of the joint

estate, and not from her separate property that was excluded from the

joint estate. But the court accepted the respondents' submission that the

debt is incurred by the person who is the debtor, and not by the person's

estate; the latter is merely the source from which the debt is recovered. So

the insolvent debtors are both spouses, because the debts incurred by one

spouse are generally the debts of both of them in a marriage in

community of property. The spouses, not the joint estate, are therefore

insolvent debtors.

Nugent JA stated that once it is accepted that debts are incurred by

232

(2003) 15 SA Merc LJ

persons rather than by their estates, and that in marriages in community

of property both spouses are generally liable for payment of the debts

that are incurred by one of them,

`it follows that a creditor may look to the estates of both the debtors for recovery of the

debt. In the case of a spouse such as the appellant that estate comprises not only her

undivided interest in the joint estate but also her separate property that falls outside the

joint estate' (at 675DE).

Property that is separately owned by one of the spouses in community

of property is considered separate in the sense that it may be dealt with

separately by the spouses between themselves and upon dissolution of the

marriage (at 675F).

The remedies of the Insolvency Act apply to both spouses in recovering

the debt that is due by both of them. The Act does not recognize separate

estates of a debtor, nor does it allow for the sequestration of only part of

a debtor's estate. An order of sequestration, according to the judge, has

the effect of divesting the debtor of the whole of his or her estate (at

675GJ).

Strictly within the confines of this case these observations may be

correct. But within the broader context of insolvency law they should

be qualified. It is true that section 20(1)(a) has the effect of divesting the

insolvent of his or her estate and vesting it finally in the trustee. But it is

not true that there is no provision for only part of the debtor's estate to be

available to his or her creditors (at 676BC). Actually, section 20(2)( b)

specifically provides for such an eventuality by its reference to section 23.

Paragraphs (a) and (b) of section 20(2) define the content of this

(divested) insolvent estate, which content does not include certain

property that belongs to the insolvent debtor but that is specifically

excluded from the insolvent estate. This excluded property belongs to

another estate that is owned by the insolvent debtor but that is not under

sequestration. One can assume that the provisions of the Act in respect of

excluded assets refer partly to such excluded assets, and to the

consequential creation of another estate after the debtor's sequestration, and it appears that the court in Du Plessis referred to the Act in this

context.

Whether or not excluded assets ever form part of the debtor's insolvent

estate is a topic for another discussion. In at least three instances, though,

it would appear that assets that belong to an insolvent debtor definitely

never form part of his or her insolvent estate.

In the first instance, the Long-Term Insurance Act 52 of 1998 provides

for the protection of policy benefits under certain long-term policies:

certain policy benefits that are provided, or that are to be provided, and

assets acquired with such benefits, are not `. . . liable to be attached or

subjected to execution under a judgment of a court or form part of his

or her [the insured's] insolvent estate' (s 63(1)(a)).

CAN AN INHERITANCE EVADE AN INSOLVENT COMMUNAL ESTATE?

233

Secondly, section 23(8) of the Insolvency Act states:

`The insolvent may for his own benefit recover any compensation for any loss or damage

which he may have suffered, whether before of after the sequestration of his estate, by

reason of any defamation or personal injury. . . .'

In De Wet NO v Jurgens supra at 49AC, Rabie AJA stated the

following with reference to section 23(8):

`Die Wet van 1953 het beperkings op die vrou se reg om self vir persoonlike beserings te

dagvaar, verwyder . . . en dit gee ook aan haar 'n reg van beheer oor geld wat sy as

vergoeding ontvang wat sy voorheen nie gehad het nie . . . maar dit beteken nie, soos

aangevoer is, dat hierdie Wet 'n remedie geskep het wat voor 1953 nie bestaan het nie. Die

vrou kon immers met die bystand van die man aksie ingestel het, of die man kon self

gedagvaar het, en indien die aksie suksesvol was, het die gemeenskaplike boedel, en

derhalwe ook die vrou, die voordeel van die betaalde vergoeding gehad.'

But the communal estate to which Rabie AJA referred could not have

been the insolvent communal estate, since the `betaalde vergoeding' to

which he referred was an asset that was excluded from the insolvent estate

by virtue of section 23(8). So this asset would not have been subject to the

claims of the creditors of the insolvent communal estate. I shall again

consider the status of assets of this nature below.

In Santam Ltd v Norman & another 1996 (3) SA 502 (C), the underlying

purpose of section 23(8) and the other provisions of section 23 was

considered. The court quoted Steyn J in Kruger v Santam Versekeringsmaatskappy Bpk 1977 (3) SA 314 (O) at 317CF:

`Die Wetgewer is deur middel van die Insolvensiewet prime r daarop ingestel om die

insolvent en sy bates van mekaar te skei, beheer van die boedel aan die kurator oor te dra

en die bates na die krediteure op 'n sekere rangorde van voorkeur oor te skuif. Die

liggaam van die insolvent word egter nie so oorgeskuif nie. Sy persoonlike integriteit bly

onaangetas en sy status gedeeltelik ook. . . . In daardie sin is die insolvent se liggaam 'n

``bate'' wat hy tot voordeel van homself en sy familie na sekwestrasie kan

aanwend. . . . Skade aan sy vlees of gees berokken is gevolglik sy skade en vergoeding

daarvoor kom hom persoonlik en vir sy eie voordeel toe' (original emphasis).

This exposition of the underlying purpose of these provisions was

approved by the Appellate Division in Santam Versekeringsmaatskappy

Bpk v Kruger 1978 (3) SA 656 (A).

In Santam Ltd v Norman (supra), the court also confirmed that

section 23(8) does not only apply to compensation recovered after

sequestration it applies to damages suffered before or after the

sequestration of the insolvent's estate. Traverso J said (at 508EH):

`I can find no reason in logic to distinguish between a case where litis contestatio occurred

prior to sequestration and where an award was made prior to sequestration. The

underlying purpose of the legislation remains the same, namely to protect that which is

attached to the person of the insolvent, and to enable the insolvent to retain it for his own

benefit to the exclusion of his creditors.

`To demonstrate the inequity that will result if I had to uphold [counsel for the

defendant's] argument, I will give the following hypothetical examples.

`If X receives an award prior to sequestration which includes a component for future

loss of earning capacity, will this award vest in the trustee? If X receives an award which

is earmarked to enable him to purchase a new wheelchair at regular intervals for the rest

of his life, could the legislature ever have intended that such an award would vest in the

trustee? The answer to this question is self-evident.'

234

(2003) 15 SA Merc LJ

Thirdly, the insolvent may recover pensions for his or her own benefit

(s 23(7)). These benefits, it appears, do not form part of the debtor's

insolvent estate (Matanzima v Minister of Welfare and Pensions & others

1990 (4) SA 1 (TkA)).

Does the Insolvency Act Recognize Separate Estates in Insolvency?

As I have noted above, section 23 states that subject to its provisions

and those of section 24, `all property acquired by an insolvent shall

belong to his estate'. This relates, generally, to property acquired by the

debtor after sequestration. Section 23 then provides for certain property

that is specifically excluded from the insolvent estate (see also section 63

of the Long-Term Insurance Act). If, as the court stated in Du Plessis v

Pienaar (supra), the Act does not recognize separate estates of a debtor,

in which estate will such excluded assets reside? Sequestration divests the

insolvent of his or her entire insolvent estate, but this does not mean that

he or she is divested of property that does not form part of the insolvent

estate. Such excluded property vests in the debtor's `new' estate that does

not form part of his or her insolvent estate (see Miller v Janks 1944 TPD

127). Section 24 regulates property in possession of the insolvent after

sequestration. Section 24(2) states that whenever the insolvent acquired

the possession of any property, such property, if claimed by the trustee of

the insolvent estate, is deemed to belong to that estate unless the contrary

is proved. If the contrary is proved, to what estate will such property

belong if not to the insolvent estate? Unless it is proved that the

property belongs to a third party, it belongs to the insolvent debtor but

not to his or her insolvent estate. An example of assets so acquired is

property purchased with income that is exempt under section 23, or the

Long-Term Insurance Act. So I believe that the Insolvency Act does

recognize separate estates of a debtor, and in this way it does allow for

the sequestration of only part of a debtor's estate. Also, by implication,

this means that a debtor, when he or she incurs a debt, is capable in law of

binding only part of his or her estate. From a practical point of view this

is important to recognize, as it is not inconceivable that an application for

the sequestration of an unrehabilitated insolvent's `new' estate may come

before the court.

Separate Property in a Communal Estate

In respect of the separate property for which the Matrimonial Property

Act specifically provides, the court in Du Plessis v Pienaar (supra) found

that the existence of such separate property did not result in the creation

of a separate estate comprising all property that was excluded from the

joint estate and which was out of reach from the spouses' joint creditors.

The existence of such a novel entity, the court found, would result in

`startling anomalies for it would suggest that a debtor might be insolvent

CAN AN INHERITANCE EVADE AN INSOLVENT COMMUNAL ESTATE?

235

in relation to one estate and not insolvent in relation to the other' (at

677E). The Matrimonial Property Act, the court concluded, recognized

the existence of separate property in the relationship between the spouses

between themselves, but it did not affect the rights of third parties (at

677EF).

But the above discussion has shown that it is not so startlingly

anomalous to find that a debtor may be insolvent in relation to one estate

but not insolvent in relation to another. One last example where this

`anomaly' again may occur is where a spouse, married in community of

property, has recovered damages for a delict committed against him or

her. Section 18(a) of the Matrimonial Property Act excludes such

damages from the joint estate; the damages become the spouse's separate

property. At the same time, damages for defamation or personal injury

are excluded from the spouses' insolvent estate by section 23(8) of the

Insolvency Act. So assets emanating from such damages may be out of

reach of one of the spouses between themselves, and, at the same time,

they may be out of reach of the creditors of the insolvent (joint) estate.

Where, then, do assets of this nature reside? Is this not a separate

estate within a communal marital estate? If it is, can such separate and

excluded income, or assets acquired with such income, ever form part of

an insolvent estate?

Conclusion

Although questions may arise from both the Badenhorst and the Du

Plessis judgments, it appears that, generally, the only assets that may be

excluded from a communal insolvent estate are those that are specifically

excluded by virtue of the provisions of the Insolvency Act, or some other

legislation such as the Long-Term Insurance Act. Such assets are beyond

the reach of the creditors of the communal estate. But as long as both

spouses in a marriage in community of property are considered to be the

debtors in respect of debts incurred by either of them, it is apparently not

possible, other than by legislation, in a marriage in community of

property, to create a separate estate beyond the reach of the creditors

of the joint estate. The primary problem with this scenario is, of course,

the particular marital bed of roses that the spouses have chosen to share.

It has proved to be thorny in both the Badenhost and the Du Plessis cases,

one that may have been avoided if the parties had been advised to enter

into a marriage out of community of property, or to change to such a

regime before blood was drawn.

It is interesting to note that in many foreign jurisdictions the institution of

a marriage in community of property is unknown. Generally, in those

jurisdictions, the problems encountered here are also unknown. In his

concluding remarks the judge in the Badenhorst case said that `[d]ie resultaat

mag onbillik voorkom, maar dit is myns insiens 'n onafwendbare gevolg van

die applikante se huwelik binne gemeenskap van goed' (at 172C).

236

(2003) 15 SA Merc LJ

The results of these cases certainly leave one with feelings of inequity,

and where a will is involved, with the image of a testator turning in his or

her grave. One can also but wonder why this issue was not considered

thoroughly by the drafters of the Matrimonial Property Act. That Act

appears to be misleading when it refers to the creation of `separate

estates' for spouses married in community of property but then fails to

consider the rights of third parties as against these estates. Legislative

intervention is perhaps overdue.

It is also ironic that although a testator cannot exclude an inheritance

from an insolvent estate by means of a clause such as that used in the Du

Plessis and Badenhorst cases, the heir can attain the result that the

testator had in mind by the mere act of repudiation (see Kellerman NO v

Van Vuren & others 1994 (4) SA 336 (T); Klerck and Scharges NNO v Lee

& others 1995 (3) SA 340 (SE); Boland Bank Bpk v Du Plessis 1995 (4) SA

113 (T); Simon NO & others v Mitsui & Co Ltd & others 1997 (2) SA 475

(W); Durandt NO v Pienaar NO & others 2000 (4) SA 869 (C); Wessels

NO v De Jager en 'n ander NNO 2000 (4) SA 924 (SCA); RG Evans

`Should a Repudiated Inheritance or Legacy Be Regarded as Property of

an Insolvent Estate?' (2002) 4 SA Merc LJ 690; JC Sonnekus `Adiasie,

Insolvensie en Historiese Perke aan die Logiese' 1996 TSAR 240;

JC Sonnekus `Delatio en Fallacia in die Hoogste Hof' 2000 TSAR 793;

Richard Stevens `RIP Testator: Wessels NO v De Jager en 'n ander NNO'

(2001) 118 SALJ 230). While the heir will lose all rights to the inheritance

if he or she repudiates, he or she will also ensure that the inheritance is

excluded from the insolvent estate. The inheritance will then, generally,

devolve upon another person, either in terms of the relevant will or under

the law of intestate succession. This result, one may argue, is more in line

with what the testator probably intended.

To conclude: administrators of estates should be aware that it is not

possible to exclude testamentary assets from an heir's insolvent estate

merely by inserting in a will an exclusionary clause like that in the above

cases. An inheritance will not by this method evade an insolvent

communal estate. This observation of course applies in respect of any

heir, and not only an heir who may be married in community of property.

If a flawed clause of this nature is included in a will, and the insolvent heir

adiates, then that inheritance becomes part of his or her insolvent estate

for the benefit of the creditors. But should the heir repudiate the

inheritance, it will evade the insolvent estate, joint or single.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Vitug Vs CA, 183 SCRA 755Documento2 pagineVitug Vs CA, 183 SCRA 755Greta Fe DumallayNessuna valutazione finora

- VITUG VS CA (Digest)Documento4 pagineVITUG VS CA (Digest)Valerie San MiguelNessuna valutazione finora

- 43401-Article Text-39971-1-10-20090610Documento20 pagine43401-Article Text-39971-1-10-20090610MargexNessuna valutazione finora

- Updated Property Case SummariesDocumento191 pagineUpdated Property Case SummariesP RamsNessuna valutazione finora

- ISSN 1727-3781: Matrimonial Property Regimes and Damages: The Far Reaches of The South African ConstitutionDocumento20 pagineISSN 1727-3781: Matrimonial Property Regimes and Damages: The Far Reaches of The South African ConstitutionPanashe BwoniNessuna valutazione finora

- Wills and Testamentary SuccessionDocumento147 pagineWills and Testamentary SuccessionindignumNessuna valutazione finora

- Succession. Set 2.: Rufino B. Javier Law Office For Petitioner. Quisumbing, Torres & Evangelista For Private RespondentDocumento45 pagineSuccession. Set 2.: Rufino B. Javier Law Office For Petitioner. Quisumbing, Torres & Evangelista For Private RespondentJoni PurayNessuna valutazione finora

- Cases WillsDocumento23 pagineCases WillsBelle CaldeaNessuna valutazione finora

- Conflict of Laws in Insolvency Transaction AvoidanceDocumento32 pagineConflict of Laws in Insolvency Transaction Avoidancevidovdan9852Nessuna valutazione finora

- Barratt - Mine and Mine Alone. Ju Salj v130 n4 A4Documento17 pagineBarratt - Mine and Mine Alone. Ju Salj v130 n4 A4toritNessuna valutazione finora

- Sucession AllDocumento865 pagineSucession AllMark MlsNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitug v. CADocumento2 pagineVitug v. CAJulianNessuna valutazione finora

- Supreme Court upholds survivorship agreementDocumento30 pagineSupreme Court upholds survivorship agreementAlfie OmegaNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitug vs. Court of Appeals: GR. No. 82027, March 29, 1990Documento2 pagineVitug vs. Court of Appeals: GR. No. 82027, March 29, 1990Lucas Gabriel Johnson67% (3)

- Vitug Vs Court of Appeals 183 SCRA 755Documento3 pagineVitug Vs Court of Appeals 183 SCRA 755Epictitus StoicNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitug v. CA Validates Survivorship AgreementDocumento2 pagineVitug v. CA Validates Survivorship AgreementqueshemNessuna valutazione finora

- Cus AssignmentDocumento14 pagineCus AssignmentKAGISO SIMPHIWE HLONGWANENessuna valutazione finora

- Ex Parte GeldenhuysDocumento8 pagineEx Parte GeldenhuysTafadzwa ChamisaNessuna valutazione finora

- Valdez vs. TuasonDocumento4 pagineValdez vs. TuasonJeanne CalalinNessuna valutazione finora

- Court upholds survivorship agreement for joint bank accountDocumento5 pagineCourt upholds survivorship agreement for joint bank accountTanya PakyoNessuna valutazione finora

- Collation On Law of SuccessionsDocumento26 pagineCollation On Law of SuccessionsTegbaru WoldemichaelNessuna valutazione finora

- G.R. No. 82027. March 29, 1990. Romarico G. Vitug, Petitioner, vs. The Honorable Court of Appeals and Rowena FAUSTINO-CORONA, RespondentsDocumento9 pagineG.R. No. 82027. March 29, 1990. Romarico G. Vitug, Petitioner, vs. The Honorable Court of Appeals and Rowena FAUSTINO-CORONA, RespondentsKrisha FayeNessuna valutazione finora

- Divorce MutualDocumento23 pagineDivorce MutualdammadminNessuna valutazione finora

- G.R. No. 82027 March 29, 1990 ROMARICO G. VITUG, Petitioner, The Honorable Court of Appeals and Rowena Faustino-Corona, RespondentsDocumento3 pagineG.R. No. 82027 March 29, 1990 ROMARICO G. VITUG, Petitioner, The Honorable Court of Appeals and Rowena Faustino-Corona, RespondentsMac Duguiang Jr.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Succession AdditionalDocumento10 pagineSuccession AdditionalGabe BedanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Matrimonial Proceedings and Property ActDocumento181 pagineMatrimonial Proceedings and Property Actpuff2Nessuna valutazione finora

- Property LawDocumento17 pagineProperty LawRuqaiyah fahimNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Digest - Civil Law - Module 3 and 4Documento4 pagineCase Digest - Civil Law - Module 3 and 4Dan R. MilladoNessuna valutazione finora

- Dael vs. Intermediate Appellate CourtDocumento17 pagineDael vs. Intermediate Appellate CourtPrincess MadaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitug v. CA (Digest)Documento2 pagineVitug v. CA (Digest)ShielaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2023 Week 6-1Documento21 pagine2023 Week 6-1Joshua OnckerNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitug V Corona PDFDocumento1 paginaVitug V Corona PDFyzarvelascoNessuna valutazione finora

- Produce The Note The UCC and The Law of MerchantsDocumento26 pagineProduce The Note The UCC and The Law of MerchantssouxsieNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitug v. CA, GR 82027, 3:29:1990Documento6 pagineVitug v. CA, GR 82027, 3:29:1990Joffrey UrianNessuna valutazione finora

- First Respondent's Heads of Argument-6123Documento12 pagineFirst Respondent's Heads of Argument-6123boipelocarolbubumphahleleNessuna valutazione finora

- #21. Vitug Vs CADocumento4 pagine#21. Vitug Vs CAeizNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitug v. CADocumento2 pagineVitug v. CAGab SollanoNessuna valutazione finora

- Digest Vitug v. CADocumento1 paginaDigest Vitug v. CAAlelie MalazarteNessuna valutazione finora

- The Harmonisation of Private InternationalDocumento27 pagineThe Harmonisation of Private InternationalFernando AmorimNessuna valutazione finora

- Notes by Atty Reena NievaDocumento21 pagineNotes by Atty Reena NievaHardmon SerranotzkyNessuna valutazione finora

- Ablaza Vs RepublicDocumento16 pagineAblaza Vs RepublicCla SaguilNessuna valutazione finora

- Rufino B. Javier Law Office For Petitioner. Quisumbing, Torres & Evangelista For Private RespondentDocumento2 pagineRufino B. Javier Law Office For Petitioner. Quisumbing, Torres & Evangelista For Private RespondentcsncsncsnNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitug v. CA rules survivorship agreement validDocumento1 paginaVitug v. CA rules survivorship agreement validJamie Dilidili-TabiraraNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitug vs. Court of Appeals, 29 March 1999Documento2 pagineVitug vs. Court of Appeals, 29 March 1999Jerry SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Conflict of Laws in Divorce CasesDocumento32 pagineConflict of Laws in Divorce CasesAfsana AliNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitug v. CA (183 SCRA 755)Documento1 paginaVitug v. CA (183 SCRA 755)Julie Anne CäñoNessuna valutazione finora

- Ownership of The Family Home HandoutDocumento13 pagineOwnership of The Family Home HandoutSammy AlroubNessuna valutazione finora

- Court upholds nullity of marriage due to psychological incapacityDocumento38 pagineCourt upholds nullity of marriage due to psychological incapacityMikko AcubaNessuna valutazione finora

- Civil Law Succession Reviewer Covering Articles 840-1105Documento112 pagineCivil Law Succession Reviewer Covering Articles 840-1105Rein Drew100% (1)

- Costs-Godwin-Bermuda Sept 28 2017 2Documento22 pagineCosts-Godwin-Bermuda Sept 28 2017 2Anonymous UpWci5Nessuna valutazione finora

- 2 Marriage and Civil PartnershipsDocumento22 pagine2 Marriage and Civil PartnershipsMalena BerardiNessuna valutazione finora

- He 9780198869382 Chapter 16Documento34 pagineHe 9780198869382 Chapter 16talisha savaridasNessuna valutazione finora

- 2023+week+5 Lecture+2Documento22 pagine2023+week+5 Lecture+2Joshua OnckerNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitug Vs CA 188 Scra 755 (Digest)Documento1 paginaVitug Vs CA 188 Scra 755 (Digest)Leogen TomultoNessuna valutazione finora

- LAW OF SUCCESSION CATDocumento18 pagineLAW OF SUCCESSION CATkirrdennkipNessuna valutazione finora

- Digest MoDocumento33 pagineDigest MoWangyu KangNessuna valutazione finora

- Validity of survivorship agreement over joint bank accountDocumento2 pagineValidity of survivorship agreement over joint bank accountAlexandraSoledadNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitug V CADocumento4 pagineVitug V CANichol Uriel ArcaNessuna valutazione finora

- Dissolution of Marriage Lecture 3Documento11 pagineDissolution of Marriage Lecture 3Jr NeyNessuna valutazione finora

- Law School Survival Guide (Volume I of II) - Outlines and Case Summaries for Torts, Civil Procedure, Property, Contracts & Sales: Law School Survival GuidesDa EverandLaw School Survival Guide (Volume I of II) - Outlines and Case Summaries for Torts, Civil Procedure, Property, Contracts & Sales: Law School Survival GuidesNessuna valutazione finora

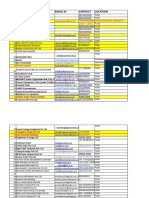

- Stock Exchange Listings and Professional Advisors RequirementsDocumento52 pagineStock Exchange Listings and Professional Advisors RequirementsAllan Sabz NcubeNessuna valutazione finora

- Lease DocumentDocumento10 pagineLease DocumentAllan Sabz NcubeNessuna valutazione finora

- KOEKEMOER MComm TR13 217Documento72 pagineKOEKEMOER MComm TR13 217Allan Sabz NcubeNessuna valutazione finora

- Delict B 3rd TermDocumento52 pagineDelict B 3rd TermAllan Sabz NcubeNessuna valutazione finora

- 0 - Theories of MotivationDocumento5 pagine0 - Theories of Motivationswathi krishnaNessuna valutazione finora

- Smart Card PresentationDocumento4 pagineSmart Card PresentationNitika MithalNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 3: The Catering Service Industry Topic: Catering Service Concept Digest (Discussion)Documento5 pagineUnit 3: The Catering Service Industry Topic: Catering Service Concept Digest (Discussion)Justin MagnanaoNessuna valutazione finora

- COA Full Syllabus-CSEDocumento3 pagineCOA Full Syllabus-CSEAMARTYA KUMARNessuna valutazione finora

- Graphics Coursework GcseDocumento7 pagineGraphics Coursework Gcseafiwhlkrm100% (2)

- Company Name Email Id Contact Location: 3 Praj Industries Limited Yogesh960488815Pune-Nagar Road, SanaswadiDocumento65 pagineCompany Name Email Id Contact Location: 3 Praj Industries Limited Yogesh960488815Pune-Nagar Road, SanaswadiDhruv Parekh100% (1)

- Communication Box Specification V1.0Documento3 pagineCommunication Box Specification V1.0Natan VillalonNessuna valutazione finora

- Black Bruin Hydraulic Motors On-Demand Wheel Drives EN CDocumento11 pagineBlack Bruin Hydraulic Motors On-Demand Wheel Drives EN CDiego AlbarracinNessuna valutazione finora

- 2022 Semester 2 Letter To Parents - FinalDocumento7 pagine2022 Semester 2 Letter To Parents - FinalRomanceforpianoNessuna valutazione finora

- 1st WeekDocumento89 pagine1st Weekbicky dasNessuna valutazione finora

- Opening Up The Prescriptive Authority PipelineDocumento10 pagineOpening Up The Prescriptive Authority PipelineJohn GavazziNessuna valutazione finora

- Frequently Asked Questions (And Answers) About eFPSDocumento10 pagineFrequently Asked Questions (And Answers) About eFPSghingker_blopNessuna valutazione finora

- Data Collection ProcedureDocumento58 pagineData Collection ProcedureNorjenn BarquezNessuna valutazione finora

- RA 8042 and RA 10022 ComparedDocumento37 pagineRA 8042 and RA 10022 ComparedCj GarciaNessuna valutazione finora

- Banking Software System Monitoring ToolDocumento4 pagineBanking Software System Monitoring ToolSavun D. CheamNessuna valutazione finora

- Pg-586-591 - Annexure 13.1 - AllEmployeesDocumento7 paginePg-586-591 - Annexure 13.1 - AllEmployeesaxomprintNessuna valutazione finora

- E.R. Hooton, Tom Cooper - Desert Storm - Volume 2 - Operation Desert Storm and The Coalition Liberation of Kuwait 1991 (Middle East@War) (2021, Helion and CompanyDocumento82 pagineE.R. Hooton, Tom Cooper - Desert Storm - Volume 2 - Operation Desert Storm and The Coalition Liberation of Kuwait 1991 (Middle East@War) (2021, Helion and Companydubie dubs100% (5)

- Bridge Ogres Little Fishes2Documento18 pagineBridge Ogres Little Fishes2api-246705433Nessuna valutazione finora

- Paulson 2007 Year End Report Earns Nearly 600Documento16 paginePaulson 2007 Year End Report Earns Nearly 600Tunaljit ChoudhuryNessuna valutazione finora

- Flyaudio in An 08 Is250 With Factory Nav InstructionsDocumento2 pagineFlyaudio in An 08 Is250 With Factory Nav InstructionsAndrewTalfordScottSr.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Nippon Metal Primer Red Oxide TDSDocumento2 pagineNippon Metal Primer Red Oxide TDSPraveen KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Depreciation Methods ExplainedDocumento2 pagineDepreciation Methods ExplainedAnsha Twilight14Nessuna valutazione finora

- Yale Smart Door Locks GuideDocumento50 pagineYale Smart Door Locks GuidejaganrajNessuna valutazione finora

- Y-Site Drug Compatibility TableDocumento6 pagineY-Site Drug Compatibility TableArvenaa SubramaniamNessuna valutazione finora

- Integrated Building Management Platform for Security, Maintenance and Energy EfficiencyDocumento8 pagineIntegrated Building Management Platform for Security, Maintenance and Energy EfficiencyRajesh RajendranNessuna valutazione finora

- Optimization TheoryDocumento18 pagineOptimization TheoryDivine Ada PicarNessuna valutazione finora

- The Problem and Its SettingDocumento36 pagineThe Problem and Its SettingRodel CamposoNessuna valutazione finora

- Dhabli - 1axis Tracker PVSYSTDocumento5 pagineDhabli - 1axis Tracker PVSYSTLakshmi NarayananNessuna valutazione finora

- Catalog CONSUDocumento19 pagineCatalog CONSUVăn Nam PhạmNessuna valutazione finora

- Tabel Condenstatori SMDDocumento109 pagineTabel Condenstatori SMDAllYn090888Nessuna valutazione finora