Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Is Is Tlie

Caricato da

reacharunk0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

14 visualizzazioni1 paginaljljljl

Titolo originale

EN(604)

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoljljljl

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

14 visualizzazioni1 paginaIs Is Tlie

Caricato da

reacharunkljljljl

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 1

582

THEORY OF ARCIIITECTUIIE, Book 11.

containing stones of the same thickness. The masonry is then laid in liorizontal courses, but

not alw.iys confined to the same tliickness. 'J'he uncoursed rubble wall is formed by

laying the stones in tlie wall as tiiey c ime to hand, without gauging or sorting, being

))reparL'd only by knocking oti" the sharp angles with the thick end of the scabbling

hanuner.

19'i26. Ai)parently, wherever there was any difficulty in obtaining stone, the mediaeval

builders emplovcd the worst of all methods of construction in walling, viz., concrete or

riibble-work l)etween the two faces of squared stone. Jn the early period of media-val art,

flint or rough rubble, with "sliort and long work" to the quoins, seems to have been very

general ; this

"

short and long work

"

was also used in faced walls

;

in both cases the short

work consists of stone u))on its bed, and alternates with the long work or stone upriglit

:

the short work ought to serve as liond tlu-ouglioiit the walls. In the

1

'ith century

tiie use of rubble in conjunction witli worked sione became freijiient. The chief defect,

frequently considered one of the merits, of this system, consists in the omis-iion of sufficient

bond both in piers and walls

;

the occurrence of joints in angles is too frequent ; in fact,

any expedient seemed better than the trouble of making a back-joint.

I9'22c. Kentish IlAcsroNE. This material, now so extensively employed for mediaeval

work in the metropolis and suburbs, is never used intn-naUy, as it .sweu/s, that is, the con-

densed moisture from the atmosphere is not absorbed, and will show itself even through two

coats of plastering, //as.' oc/e sfo?ie, however, which is the sandstone separating the beds of

the ragstone, the sand being sufficiently agglutinated to allow of its being raised in blocks,

must never be used extenialli/. It is easily worked, and makes a good lining for ragstone

walls, as it does not sweat. It should be roughly squared, for if not done, the crumbling

nature of the stone would endanger the security of the work, should it be exposed to any

luiequal pressure : it must not be jjlaced where it would be exposed to very great ])ressure,

as in arches, jambs, &c. Hassock may l)e procured in London at from (is. to 75. per cord

(3

feet cube), in roughly stjuared pieces; while rough rag is about 5s. per ton, and rag

headers about 1 2s. 6d. ]>er ton.

192_'J. Sunk and mouliied work in so hard a material is to be avoided, and so much

wrought surface would cause decay. In using ragstone ashlar, it must be l.iid upon its na-

tural bed, otherwise rai)id decay will almost certainly follow, arising from the thinness of the

strata, for blocks of a large size can seldom be entirely freed from hassock

;

and even wliat

ajjpears to the eye as blue stone, retains for a considerable distance inward the jierishmg

nature of its enveloping crust. A block of ragstone, if the face be worked, will present in

d:mip weather an appearance i)recisely similar to the heart and sap of timber. In the cnse

of cojiings, &c., where one bed is exposed, the stone siiould he

skiffled

(or /niohlilcd) as nuicli

as possible from the upper side, so as to expose only the soundest portion of the stone to

the action of tiie atmosphere. In some situations, as mullions, door and window jamhs,

an unsightly ajjpearance would lie produced by too exact an attention to the beds of the

stone, as the ashlar is generally too small to range with more than one course of headers.

In these cases the old masons seem to have dejiarted from their usual rule, and to have set

the blocks on end, so as to embrace two or three ourses

;

but as the depth of the block re-

quired to work an ordinary jamb or mullion is not very great, it is not difficult to get the

whole thickness required out of the heart of the stone.

1922e. Stone of the smaller layings are generally worked into headers; it is common to

work one side of the stone to a rough face with parallel sides, without paying much atten-

tion to the beds and joints, whicli often recede at an acute angle with the f;ice, so as to

bring the stones, when laid, tcj a closer joint. Such stones, however, mu^t be pro])erly

pinned in behind, and carefully bonded with the work at back. Headers are generally

knocked out to six, seven, eight, or nine inch gauge for the height ; the length and tail

being determined by the size of the stone : on the face they do not vary much from the

square form. Formerly lieadcrs were set on their natural bed, therefore it is not unusual

to find stones in an old wall entirely gone from this cause.

1922y. In the Whitelands bridge bed, a very free working stone of a bluish colour can

be got 12 feet long with certainty, and the Horsebridge bed yields a good stone to a

length of 15 feet. Tiie white rag, the lowest of the beds in the quarry, tumbles to pieces

on exposure to the air (Whichcord, Kentish Bag&tone, 1846).

1922p. In its mechanical properties, ragstone possesses some of the qualities of granite,

though in an inferior degree. In respect to resistance to pressure, it stands next to granite

in the list of British stones

;

but when loaded for a transverse strain, the numerous vents

to which even the best layings are liable, renders it imtnistworihy for lintels, or in a

suspended position, without much precaution. In the former case of lintels and architraves,

three stones, arch jointed, gives the recjuisite security.

1922A. WniNSTONE, a material, in one form or another, found almost over all Scotland,

makes a very durable arch for bridge woik, when well built with good mortar, the stone

being in its natiu-e weather proof. In the neighbourhood of Edinburgh, whinstone arches

have been erected since about 1770, the greatest sj)an lieing about 60 feet The Messrs.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Mud ArchitectureDocumento27 pagineMud ArchitectureShivansh KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Construction Materials and Techniques in Persian ArchitectureDocumento18 pagineConstruction Materials and Techniques in Persian ArchitecturesarosathishcNessuna valutazione finora

- Store Quality Audit ChecklistDocumento6 pagineStore Quality Audit ChecklistTurboyNavarroNessuna valutazione finora

- It It: ( - FiffDocumento1 paginaIt It: ( - FiffreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Number: Tlic TlieDocumento1 paginaNumber: Tlic TliereacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- It IsDocumento1 paginaIt IsreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- ENDocumento1 paginaENreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- En (1334)Documento1 paginaEn (1334)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- London Morar MayDocumento1 paginaLondon Morar MayreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- En (1279)Documento1 paginaEn (1279)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Who Edmund: Make MadeDocumento1 paginaWho Edmund: Make MadereacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Common: Till Is It TlieDocumento1 paginaCommon: Till Is It TliereacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Re PointingDocumento12 pagineRe PointingBen Copper100% (1)

- 1922 - Building in Cob and Pisé de Terre. A Collection of Notes From Various Sources On The Construction of Earth WallsDocumento51 pagine1922 - Building in Cob and Pisé de Terre. A Collection of Notes From Various Sources On The Construction of Earth WallsParisTiembi100% (1)

- Rubble WorkDocumento5 pagineRubble WorkKishan KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Foundations: ChapDocumento1 paginaFoundations: ChapreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Construction Technology: Stonework, Brickwork, and Block WorkDocumento41 pagineConstruction Technology: Stonework, Brickwork, and Block WorkWenny Dwi Nur AisyahNessuna valutazione finora

- MC Tracing Winter 2007Documento2 pagineMC Tracing Winter 2007Mark JurusNessuna valutazione finora

- Hyper EngineeringDocumento8 pagineHyper Engineering17-122 Venkatesh babuNessuna valutazione finora

- Of Architecture.: TliisDocumento1 paginaOf Architecture.: TliisreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Yanmar Mini Excavator b15 3 Wiring Diagrams z17245 1021dDocumento22 pagineYanmar Mini Excavator b15 3 Wiring Diagrams z17245 1021dtinatran260595xec100% (124)

- En (1374)Documento1 paginaEn (1374)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Carpentry.: Tlieii ItDocumento1 paginaCarpentry.: Tlieii ItreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Concrete: Sucli Ito Gra - Vel, IsDocumento1 paginaConcrete: Sucli Ito Gra - Vel, IsreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Manual of Egyptian Archaeology and Guide to the Study of Antiquities in EgyptDa EverandManual of Egyptian Archaeology and Guide to the Study of Antiquities in EgyptNessuna valutazione finora

- Dokras Wada Part IIIDocumento17 pagineDokras Wada Part IIIUday DokrasNessuna valutazione finora

- Cobblestone Buildings Their Nature in General ADADocumento9 pagineCobblestone Buildings Their Nature in General ADAMuhammad Lallu HamidNessuna valutazione finora

- Egyptian Archaeology: Illustrated Guide to the Study of EgyptologyDa EverandEgyptian Archaeology: Illustrated Guide to the Study of EgyptologyNessuna valutazione finora

- May TheDocumento1 paginaMay ThereacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Bricklaying And: 'A'illDocumento1 paginaBricklaying And: 'A'illreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- The Cotswold Dry Stone Wall Specification: Initial ConsiderationsDocumento4 pagineThe Cotswold Dry Stone Wall Specification: Initial Considerations0410636Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sand Muddy Thamts London Among Much The: Iliat IsDocumento1 paginaSand Muddy Thamts London Among Much The: Iliat IsreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Much Harmony We: Fiiiisli ItDocumento1 paginaMuch Harmony We: Fiiiisli ItreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Anon 52 Coral Building MaterialDocumento10 pagineAnon 52 Coral Building MaterialHetram BhardwajNessuna valutazione finora

- Properties and Use of Construction MaterialsDocumento13 pagineProperties and Use of Construction Materialsjake masonNessuna valutazione finora

- Summary of Marcus Vitruvius: Ten Books On Architecture-Book 7Documento6 pagineSummary of Marcus Vitruvius: Ten Books On Architecture-Book 7Sumit VarmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Much We May Come: R - L - AlDocumento1 paginaMuch We May Come: R - L - AlreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Historic Window Guide PDFDocumento16 pagineHistoric Window Guide PDFOrsolya SzabóNessuna valutazione finora

- Ii'jt 17 '.: OtliersDocumento1 paginaIi'jt 17 '.: OtliersreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Wattle and DaubDocumento6 pagineWattle and DaubdolphinNessuna valutazione finora

- En (1095)Documento1 paginaEn (1095)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- BingDocumento5 pagineBingdheaNessuna valutazione finora

- Stone MasonaryDocumento47 pagineStone MasonarySantosh MakadNessuna valutazione finora

- Theory: OF ArchitectureDocumento1 paginaTheory: OF ArchitecturereacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Repointing Brick and Stone Walls: Guidelines For Best PracticeDocumento31 pagineRepointing Brick and Stone Walls: Guidelines For Best PracticeAlisa Bendas100% (2)

- Bruce King - Straw-Bale ConstructionDocumento9 pagineBruce King - Straw-Bale ConstructionagrimodenaNessuna valutazione finora

- C2 Balconies Chajjas N LintelsDocumento16 pagineC2 Balconies Chajjas N LintelsaamaniammuNessuna valutazione finora

- MC Slate #1 March 1995Documento2 pagineMC Slate #1 March 1995Mark JurusNessuna valutazione finora

- ConcreteDocumento5 pagineConcreterajukg1231544Nessuna valutazione finora

- Association For Preservation Technology International (APT) Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Bulletin of The Association For Preservation TechnologyDocumento20 pagineAssociation For Preservation Technology International (APT) Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Bulletin of The Association For Preservation TechnologyJaouad OuaâzizNessuna valutazione finora

- Much Smoky The Now: LeadDocumento1 paginaMuch Smoky The Now: LeadreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Masonry Concrete StructureDocumento194 pagineMasonry Concrete Structureshruthi SundaramNessuna valutazione finora

- The Rudiments Of Practical Bricklaying - In Six Sections: General Principles Of Bricklaying, Arch Drawing, Cutting, And Setting, Different Kinds Of Pointing, Paving, Tiling, Materials, Slating, And Plastering, Practical Geometry MensurationDa EverandThe Rudiments Of Practical Bricklaying - In Six Sections: General Principles Of Bricklaying, Arch Drawing, Cutting, And Setting, Different Kinds Of Pointing, Paving, Tiling, Materials, Slating, And Plastering, Practical Geometry MensurationNessuna valutazione finora

- Bricks: Properties and Classifications: G.C.J. LynchDocumento6 pagineBricks: Properties and Classifications: G.C.J. LynchMyra Chemyra LuvabyNessuna valutazione finora

- TilesDocumento22 pagineTilesSneha PatelNessuna valutazione finora

- It Is Is Is Is It Is IsDocumento1 paginaIt Is Is Is Is It Is IsreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Vhi. GlazingDocumento1 paginaVhi. GlazingreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Module 4 - Masonry MaterialDocumento6 pagineModule 4 - Masonry MaterialCa Lop100% (1)

- 2003 03 Gerns PDFDocumento6 pagine2003 03 Gerns PDFkyleNessuna valutazione finora

- Prospekt BGF PDFDocumento150 pagineProspekt BGF PDFreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Prospekt BGF PDFDocumento150 pagineProspekt BGF PDFreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Supplement To The Prospectuses and Summary Prospectuses For Investor Shares and Admiral™SharesDocumento65 pagineSupplement To The Prospectuses and Summary Prospectuses For Investor Shares and Admiral™SharesreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- General Terms and Conditions of The Pzu NNW (Personal Accident Insurance Pzu Edukacja InsuranceDocumento19 pagineGeneral Terms and Conditions of The Pzu NNW (Personal Accident Insurance Pzu Edukacja InsurancereacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Supplement To The Prospectuses and Summary Prospectuses For Investor Shares and Admiral™SharesDocumento65 pagineSupplement To The Prospectuses and Summary Prospectuses For Investor Shares and Admiral™SharesreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Prospekt BGF PDFDocumento150 pagineProspekt BGF PDFreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Prospekt BGF PDFDocumento150 pagineProspekt BGF PDFreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Emergency Response Quick Guide MY: 2014Documento2 pagineEmergency Response Quick Guide MY: 2014reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- En (1463)Documento1 paginaEn (1463)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- En (1462)Documento1 paginaEn (1462)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- NameDocumento2 pagineNamereacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- En (1461)Documento1 paginaEn (1461)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- En (1464)Documento1 paginaEn (1464)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- En (1459)Documento1 paginaEn (1459)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- En (1454)Documento1 paginaEn (1454)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- En (1460)Documento1 paginaEn (1460)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- En (1457)Documento1 paginaEn (1457)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- En (1456)Documento1 paginaEn (1456)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- En (1450)Documento1 paginaEn (1450)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- En (1458)Documento1 paginaEn (1458)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- En (1455)Documento1 paginaEn (1455)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- En (1452)Documento1 paginaEn (1452)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- En (1453)Documento1 paginaEn (1453)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- En (1451)Documento1 paginaEn (1451)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- En (1390)Documento1 paginaEn (1390)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- En (1388)Documento1 paginaEn (1388)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- And Rome.: in Front of The Prostyle Existed atDocumento1 paginaAnd Rome.: in Front of The Prostyle Existed atreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Mate The: (Fig. - VrouldDocumento1 paginaMate The: (Fig. - VrouldreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- En (1389)Documento1 paginaEn (1389)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- En (1387)Documento1 paginaEn (1387)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Worries About Trapping Moisture - GreenBuildingAdvisorDocumento5 pagineWorries About Trapping Moisture - GreenBuildingAdvisorgpax42Nessuna valutazione finora

- BOQ - ConcreteDocumento10 pagineBOQ - ConcreteAbhijit HavalNessuna valutazione finora

- Fire Code 2013 Handbook Chapter 2 PDFDocumento250 pagineFire Code 2013 Handbook Chapter 2 PDFAdrian TanNessuna valutazione finora

- BISNAR - PLA 412 - Activity 2 - Fundamental of Urban Design and Com ArchDocumento10 pagineBISNAR - PLA 412 - Activity 2 - Fundamental of Urban Design and Com ArchKrystal Claire BisnarNessuna valutazione finora

- LostFile PDF 94918648Documento4 pagineLostFile PDF 94918648jhsee72Nessuna valutazione finora

- Master Spec - Basic VersionDocumento13 pagineMaster Spec - Basic Versionjohntag0% (1)

- Is 1553 1989 PDFDocumento17 pagineIs 1553 1989 PDFPriyanka100% (1)

- Handy Simple ShedDocumento6 pagineHandy Simple ShedMiguel Angel Rodríguez Zenteno100% (1)

- Lecture 10.9: Composite Buildings: 1. IntroductionDocumento27 pagineLecture 10.9: Composite Buildings: 1. IntroductionBernard SenadosNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 Mar SPM Sabah Question Paper (ENG) SMKA - SABK Set1 K1Documento15 pagine1 Mar SPM Sabah Question Paper (ENG) SMKA - SABK Set1 K1Choon Hong1Nessuna valutazione finora

- 2608 Planitop Fast 330 Uk NoRestrictionDocumento4 pagine2608 Planitop Fast 330 Uk NoRestrictionFloorkitNessuna valutazione finora

- Amazing Archicad TutorialDocumento41 pagineAmazing Archicad TutorialSimona MihaiNessuna valutazione finora

- Etabs ModelingDocumento39 pagineEtabs ModelingHemal Mistry100% (10)

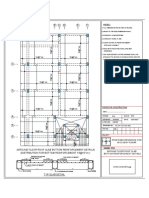

- Uday Kumar GF Slab BottomDocumento1 paginaUday Kumar GF Slab BottomNaveen Kumar KurapatiNessuna valutazione finora

- Sewers of Travon Area 1Documento2 pagineSewers of Travon Area 1Lackó PallagiNessuna valutazione finora

- Is 1200 2 1974 PDFDocumento20 pagineIs 1200 2 1974 PDFAr Hussain MojahidNessuna valutazione finora

- Design of Water Tanks-CE 05014 p3 6Documento65 pagineDesign of Water Tanks-CE 05014 p3 6engineerkranthi4055100% (1)

- General Requirements: Simple Plan Diagram For Single Storey FrameDocumento5 pagineGeneral Requirements: Simple Plan Diagram For Single Storey FrameThulasi Raman KowsiganNessuna valutazione finora

- BLDGDDocumento1 paginaBLDGDCarlo PunzalanNessuna valutazione finora

- Restoration of Georgian ShopfrontDocumento5 pagineRestoration of Georgian ShopfrontPatrick BatyNessuna valutazione finora

- Guggenheim Museum in NYCDocumento16 pagineGuggenheim Museum in NYCAkshayahNessuna valutazione finora

- Seminar 1 - Cleanroom HVAC Design - KarachiDocumento25 pagineSeminar 1 - Cleanroom HVAC Design - KarachituzlucayirNessuna valutazione finora

- Cherry and Fir BookcaseDocumento6 pagineCherry and Fir Bookcasecaballo_blanco_2100% (1)

- CRHDDocumento15 pagineCRHDjuliancabsNessuna valutazione finora

- Guidance On Designing A Heat Pump System To MIS3005 V3.1a Issue 1.0 FINALDocumento19 pagineGuidance On Designing A Heat Pump System To MIS3005 V3.1a Issue 1.0 FINALbatazivoNessuna valutazione finora

- ME8793 Process Planning Cost Estimation 1Documento27 pagineME8793 Process Planning Cost Estimation 1RAJ NAYAKNessuna valutazione finora

- High Rise StructuresDocumento70 pagineHigh Rise StructuresAnjalySinhaNessuna valutazione finora

- AWC STD342 1 WFCM2015 WindLoads 160922Documento55 pagineAWC STD342 1 WFCM2015 WindLoads 1609226Bisnaga100% (1)

- EJB, Style C Model M82 Series Junction Boxes IF 931: Installation & Maintenance InformationDocumento12 pagineEJB, Style C Model M82 Series Junction Boxes IF 931: Installation & Maintenance InformationAriel Paniagua VillenuevaNessuna valutazione finora