Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

EN

Caricato da

reacharunk0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

8 visualizzazioni1 paginaljljljl

Titolo originale

EN(602)

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoljljljl

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

8 visualizzazioni1 paginaEN

Caricato da

reacharunkljljljl

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 1

580

THEORY OF ARCHITECTURE. Book II.

1915&. Grey granite, or inoorstone as it is called in Cornwall, is got out in blocks by split-

ting it with a number of wedges applied to notches pooled in the surface of the stone, about

four inches apart. The pool /wles are sunk with the point of a pick, much in the same way

as otiier hard quarry stones are split. The harder the moorstone tiie nearer it can be split

to the scantling required. Generally speaking, granite has no planes of stratification, and

it works or cleaves equally well in every direction ; but in the porphyriiic varieties tiiere is

a rough kind of arrangement of the crystals

;

and in gneiss thei-e is a species of layer,

formed by plates of the mica, which is plainly discernible. When brought to near tlie size

required, it is first scahbled by a hammer with a cutting face

4^

inches long by li incites

wide, weighing 22 lbs.

;

then brouglit to a picked

face

with a pick or pointed hammer

weigliing

'20

lbs., formed by two acute angled triangles, joined base to base by a parallelo-

gram between them thus

<^

o

^

;

and if to he Jintly icmtyht or

fine

picked, it is further

dressed with a similar pointed hammer, reducing the roughness to a minimun. Tlie finer

finish ov

fine

axed face is (jroduced by a hammer or axe with a sharp edge on both sides,

weigliing 9lbs. ; fov fine

work the "patent axe" is also used, which is a hammer formed

of several parallel blades screwed together, capable of being taken to pieces when required

to be sharpened. Polishing can then be done by machinery, the granite being rubbed

by iron rubbers witli fine sand and water, and finished with other materials.

1915c. Aberdeen red granite possesses the property common to all granites, that of a

distinct plane of cleavage, which, though not perceptible to the eye, is at once recognisable

under the hammer of the workman, and of course can be wrought with much greater pre-

cision and cHect with the bed, than transversely to it. Tliis bed bears no traceable relation

to the natural joints of the rocks, which are indefinite in their directions; and still less

so to their stratification. The grey granites are but slightly affected with cleavage, being

capable of being blocked with the hammer with about equal facility in every direction.

The local varieties of worked granite differ somewhat from those used in England, and are,

I. Hammer-blocked, as in foundations, plinths, &c. 1 1. Scappkd blncks, squared with the

heavy pick, as in docks and heavy engineering works. III. Picked, abetter finish than

No. II, IV. Close picked, the bed and arrisLS made fair, and the outer surfaces made as

fine as the pick will make them

;

used in ashlar work, &c. V. Sinyle axed, a finer finish

than No. IV., and used in quoins, reliates, cornices, &c., in house building. And VI.

Fine axed, the finest finish before polishing, given to dressed granite by means of the

patent axe, used in the best work in house building, cemetery memorials, and as u finish to

contrast with polished work.

WALLINO.

1916. In stone walling the bedding joints are usually horizontal, and this should always,

indeed, be so wlien the top of the wall is terminated horizontally. In building bridges,

and in the masonry offence walls upon inclined surfaces, the bedding joints may follow the

general direction of the work.

1916. Footings of stone walls should be built with stones as large as maybe, squared

and of equal thicknesses in the same course, and care should be had to place the broadest

bed downwards. The vertical joints of an ujjper course are never to be allowed to fall

over those below, that is, they must be made, as it is called, to break joints. If the walls of

the superstructure be tliin, the stones composing the foundatior;s may be disposed so that

their length inay reach across each course from one side of the wall to tiie other. When

the walls are thick, and there is difficulty in procuring stones long enough to reach across

the foundations, every second stone in the course inay be a whole stone in breadth, and

each interval may consist of two stones of equal breadth, that is, ])lacing header and

stretcher alternately. If tliose stones cannot conveniently be had, from one side of tiie

wall lay a header and stretcher alternately, and from the other side another series of stones

in the same manner, so that the length of each header may be two thirds, and tlie breadth

of each stretcher one third of the lireadth of the wall, and so that the back of each lieader

may come in contact with the back of an opposite stretcher, and the side of that header may

come in contact with the side of the header adjoining the said stretcher. In foundations of

some breadth, for which stones cannot be procured of a length equal to two thirds

the breadth of the foundation, the works should be built so that the upright joints of any

course may fall on the middle of the length of the stones in the course below, and so that

tlie back of each stone in any course may iiiU on the solid of a stone or stones in the lower

coiu'se.

1917. The foundation should consist of several courses, each decreasing in breadth as

they rise by sets off' on each side of 3 or 4 inches in ordinary cases. The number of courses

is neccs'^arily regulated by tlie weight of the wall and by the size of the stones whereof

these foundations or footings are composed.

1918. Walls are inost commonly built with an ashlar facing, and backed with brick or

ftibble-work. In London, where stone is dear, the liacking is generally of brick-work,

which does not occur in the north and other ])arts, where stone is cheap and common.

Walls faced with ashlar, and backed with brick or uncoursed rubble, are liable to become

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- General Terms and Conditions of The Pzu NNW (Personal Accident Insurance Pzu Edukacja InsuranceDocumento19 pagineGeneral Terms and Conditions of The Pzu NNW (Personal Accident Insurance Pzu Edukacja InsurancereacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- En (1459)Documento1 paginaEn (1459)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Prospekt BGF PDFDocumento150 pagineProspekt BGF PDFreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- En (1464)Documento1 paginaEn (1464)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- En (1458)Documento1 paginaEn (1458)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- En (1451)Documento1 paginaEn (1451)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- And Rome.: in Front of The Prostyle Existed atDocumento1 paginaAnd Rome.: in Front of The Prostyle Existed atreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Mate The: (Fig. - VrouldDocumento1 paginaMate The: (Fig. - VrouldreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- En (1383)Documento1 paginaEn (1383)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- En (1386)Documento1 paginaEn (1386)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The The Jamb The Name Much The: Tlio CL - AssesDocumento1 paginaThe The Jamb The Name Much The: Tlio CL - AssesreacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- En (1374)Documento1 paginaEn (1374)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- En (1382)Documento1 paginaEn (1382)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- En (1376)Documento1 paginaEn (1376)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- En (1372)Documento1 paginaEn (1372)reacharunkNessuna valutazione finora

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Rediscovery' Revised - The Cooperation of Erich and Armin Von Tschermak-Seysenegg in The Context of The Rediscovery' of Mendel's Laws in 1899-1901Documento7 pagineRediscovery' Revised - The Cooperation of Erich and Armin Von Tschermak-Seysenegg in The Context of The Rediscovery' of Mendel's Laws in 1899-1901lacisagNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 21Documento22 pagineUnit 21Yuni IndahNessuna valutazione finora

- Factorisation PDFDocumento3 pagineFactorisation PDFRaj Kumar0% (1)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Transdermal Drug Delivery System ReviewDocumento8 pagineTransdermal Drug Delivery System ReviewParth SahniNessuna valutazione finora

- Report On RoboticsDocumento40 pagineReport On Roboticsangelcrystl4774Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ap Art and Design Drawing Sustained Investigation Samples 2019 2020 PDFDocumento102 pagineAp Art and Design Drawing Sustained Investigation Samples 2019 2020 PDFDominic SandersNessuna valutazione finora

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- Bilingual-Paper WDocumento4 pagineBilingual-Paper WzNessuna valutazione finora

- Fact Sheeton Canola OilDocumento15 pagineFact Sheeton Canola OilMonika ThadeaNessuna valutazione finora

- B-701 Boysen Permacoat Flat Latex2Documento7 pagineB-701 Boysen Permacoat Flat Latex2ircvpandoNessuna valutazione finora

- Type of TrucksDocumento8 pagineType of TrucksYojhan VelezNessuna valutazione finora

- Ded Deliverable List: As Per 19-08-2016Documento2 pagineDed Deliverable List: As Per 19-08-2016Isna MuthoharohNessuna valutazione finora

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Fate NumeneraDocumento24 pagineFate Numeneraimaginaari100% (1)

- VF (Kyhkkjrh VK Qfozkkulalfkku) - F'KDS"K) MRRJK (K.M& 249201Documento3 pagineVF (Kyhkkjrh VK Qfozkkulalfkku) - F'KDS"K) MRRJK (K.M& 249201RajaNessuna valutazione finora

- Today! 2 Activity Book AKDocumento10 pagineToday! 2 Activity Book AKMark Arenz Corixmir80% (5)

- Second Term English Exam: Level TCST June 2021Documento6 pagineSecond Term English Exam: Level TCST June 2021benfaresNessuna valutazione finora

- Hazard & Turn Signal Lamp CircuitDocumento2 pagineHazard & Turn Signal Lamp CircuitTanya PiriyabunharnNessuna valutazione finora

- Bleeding Disorders and Periodontology: P V & K PDocumento13 pagineBleeding Disorders and Periodontology: P V & K PAdyas AdrianaNessuna valutazione finora

- Brunei 2Documento16 pagineBrunei 2Eva PurnamasariNessuna valutazione finora

- C P P P: Rain'S Etrophysical Ocket ALDocumento54 pagineC P P P: Rain'S Etrophysical Ocket ALviya7100% (4)

- Higher Unit 11 Topic Test: NameDocumento17 pagineHigher Unit 11 Topic Test: NamesadiyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Jcpenney Roto Tiller Front in e ManualDocumento34 pagineJcpenney Roto Tiller Front in e Manualcb4pdfs100% (2)

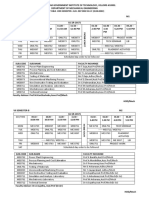

- Odd Semester Time Table Aug - Dec22 Wef 22.08.2022.NEWDocumento4 pagineOdd Semester Time Table Aug - Dec22 Wef 22.08.2022.NEWKiran KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Mechanical Reasoning - Test 2: 40 QuestionsDocumento14 pagineMechanical Reasoning - Test 2: 40 Questionskyloz60% (5)

- Acute and Chronic Gastrointestinal BleedingDocumento7 pagineAcute and Chronic Gastrointestinal BleedingMarwan M.100% (1)

- Compressed Air Pressure Drop DiagramDocumento4 pagineCompressed Air Pressure Drop DiagramycemalNessuna valutazione finora

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Part 7 Mean Field TheoryDocumento40 paginePart 7 Mean Field TheoryOmegaUserNessuna valutazione finora

- Hira - For Shot Blasting & Upto 2nd Coat of PaintingDocumento15 pagineHira - For Shot Blasting & Upto 2nd Coat of PaintingDhaneswar SwainNessuna valutazione finora

- DSE MC G11 G12 Equations Straight Lines 2023Documento6 pagineDSE MC G11 G12 Equations Straight Lines 2023ernestchan501Nessuna valutazione finora

- Excess Fluid VolumeDocumento27 pagineExcess Fluid VolumeAdrian Ardamil100% (1)

- CatalogDocumento52 pagineCatalogtalabiraNessuna valutazione finora

- The Last Dive: A Father and Son's Fatal Descent into the Ocean's DepthsDa EverandThe Last Dive: A Father and Son's Fatal Descent into the Ocean's DepthsNessuna valutazione finora