Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

2001 Ethington Frey Myers Racial Resegregation

Caricato da

Izzy MannixCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

2001 Ethington Frey Myers Racial Resegregation

Caricato da

Izzy MannixCopyright:

Formati disponibili

PUBLIC RESEARCH REPORT No.

2001-04

The Racial Resegregation

of Los Angeles County, 1940-2000

Released: May 12, 2001

Principal Authors:

Philip J . Ethington, William H. Frey, and Dowell Myers

R a c e

C o n t o u r s

2 0 0 0

S t u d y

A University of

Southern California

and

University of

Michigan

Collaborative

Project

Principal

Investigators:

Dowell Myers,

Philip J . Ethington,

Angela J ames,

William Frey

Overview of Findings:

Viewing the entire County of Los Angeles over a long period (1940-

2000) and using census tracts as the basic unit of analysis, we have found

a clear pattern of resegregation. Segregation was severe prior to 1965.

Since that date, the overall level of diversity has clearly increased, and

the emergence of Latinos as the largest single group in a no-majority

metropolis is a major milestone. But these figures hide a harder truth

that we need to confront. Levels of racial segregation remain high

among the four principal race-ethnic groups: Whites, Blacks, Hispanics,

and Asians (including Pacific Islanders). Indeed, segregation has been

increasing faster than integration since the 1960s.

Three distinct patterns are clear:

1) Whites have retreated to a periphery and the other principal

ethnic groups are less and less likely to have them as neighbors.

2) Blacks are the most isolated racial group; other racial groups have

remained highly unlikely to have them as neighbors.

3) Hispanics and Asians are becoming more isolated even as they

cause the county as a whole to be more diverse.

The patterns also make it clear that the White and Black experiences are

very similar. Both are old immigrants, with greater seniority in the

region. Although a very small number of Mexican-Americans have the

greatest seniority of all (descendants of the original Spanish settlers), the

vast majority of Latinos are, along with the vast majority of Asians, new

immigrants. Spatially, numerically, and proportionally, Whites and

Blacks are in retreat. Their increasing isolation is a function of their

Race Contours 2000 Resegregation of Los Angeles County, 1940-2000 2

shrinking size and location vis--vis the new immigrants. Latinos and Asians, by

contrast, are dynamic populations, growing spatially, numerically, and proportionally.

Their communities are exploding around many nodes of original settlement. Their

increasing isolation is a function of the classic immigrant enclave effect. As our use of

the exposure index makes clear, Whites and Blacks together have been somewhat more

likely to have Latino and Asian neighbors (simply because they are outnumbered), but

Latinos and Asians are decreasingly likely to have White or Black neighbors.

While we find these patterns to be very clear, we also want to emphasize that they are not

the whole story. This study treats Los Angeles County, the nations most populous at 9.5

million persons) as a single continuous space. Two companion Public Research Reports

from our study group analyze the wide variance of conditions among the many specific

places within LA County.

1

It is also too early draw a complete set of conclusions about many of the possible causes

or effects of these findings. Segregation is used here as a descriptive term, rather than

as a normative one. It has had, and certainly can have reprehensible causes and socially

destructive effects. It can still be, can certainly has been, caused by overt or systematic

housing or job discrimination. When linked to locational disadvantages such as high

crime rates, low job opportunity, and poor schools, it can have very negative effects. We

have other research projects

2

under way to identify these causes and effects, but this

paper sets out primarily to establish the patterns themselves.

Even within the descriptive boundaries of this analysis we have been able to identify two

causes that have operated to produced the resegregation of Los Angeles County:

a) The simple spatial arithmetic of population dynamics. The explosion of Latino

and Asian immigrant populations and steady shrinkage of White and Black

populations explains, in a statistical sense, the moderate increase in White

exposure to people of color and the rising levels of isolation among the new

immigrants.

b) The patterns of White residential behavior. Alone among the four principle racial

groups, we can say with confidence that Whites have had the freedom to settle

wherever their wealth enables them to purchase a home. They have used that

freedom to flee the growing diversity of the metropolis, either by moving out of

the county completely or by retreating to its edges.

3

1

Myers and Park (Race Contours 2000 Public Research Report 2001-05) emphasize the growth of

Racially Balanced cities since 1980 among the 177 cities of Los Angeles County, Orange, Riverside, San

Bernardino, and Ventura counties. Frey and Ethington (Race Contours Public Research Report 2001-06)

emphasize the variance in segregation indices among 77 cities of Los Angeles County from 1990 to 2000.

2

Ethington, Segregated Diversity (Haynes Foundation Final Report, August 2000) shows a very

strong correlation between White residential location and high median home prices, suggesting that the

cause of White/nonwhite segregation is a barrier of very high property values that prevents Blacks and

new immigrants (all upwardly mobile groups) from entering White neighborhoods.

3

To some extent, members of each racial group have freedom to settle where their wealth can

afford a home, and a crucial effort in our ongoing research is to better understand the voluntary decisions of

Race Contours 2000 Resegregation of Los Angeles County, 1940-2000 3

Table of Contents:

Page

1.0 Overview of Findings 1

2.0 Overview of Methods 4

2.1 The 1940-2000 Dataset 4

2.2 Definition of Racial Groups 4

2.3 Explanation of the Segregation Indices 5

2.31

The Diversity Index

5

2.32

The Index of Dissimilarity

5

2.33

The Exposure Index

6

3.0 Summary of Specific Findings 8

4.0 Detailed Findings 10

Chart 1: Overall Population Figures 10

Chart 2: Diversity Index 11

Chart 3: Index of Dissimilarity 12

Chart 4a: Exposure Index White Neighbors 13

Chart 4b: Exposure Index White Settlers 14

Chart 5a: Exposure Index Black Neighbors 15

Chart 5b: Exposure Index Black Settlers 16

Chart 6a: Exposure Index Hispanic Neighbors 17

Chart 6b: Exposure Index Black Settlers 18

Chart 7a: Exposure Index Asian Neighbors 19

Chart 7b: Exposure Index Asian Settlers 20

Map : White Majority Census Tracts, 1940-2000 21

Bibliography: Works Cited 22

people of color to locate among neighbors of their own racial group. Notwithstanding this phenomenon,

however, housing market discrimination against affluent people of color is very well documented, and

conversely, discrimination against affluent Whites has never been documented.

Race Contours 2000 Resegregation of Los Angeles County, 1940-2000 4

2.0 Overview of Methods

Questions of method loom large in studies of U.S. Census data. The two crucial areas of

methodological concern in this study are: 1) Why are the data from 1940-2000

comparable and uniform?; 2) How did we define the four principal racial groups? and

3) What do the different measures of segregation mean?

2.1 The 1940-2000 Dataset

This study is based on a uniform dataset, in which comparable data has been organized

into the 2000 Census tract boundaries, from 1940 through 2000 (N=2,055 census tracts).

We began with the Los Angeles County Union Census Tract Data Series, 1940-1990

(Ethington Kooista and DeYoung 2000), which is fitted to the 1990 census tract

boundaries. Upon release of the California census data in March of 2001, we constructed

variables for the four principal race-ethnic groups (see below) that were most compatible

with the way those racial variables were defined in 1990. The entire 1940-1990 data

series were then fitted to the 2000 census tract boundaries using ESRIs ArcInfo

software to reallocate 1990 tract aggregates in areal proportion to the polygonal overlays

of the 2000 boundaries.

2.2 Definition of Racial Groups

By convention and by virtue of their numerical prominence, social scientists and public

policy makers have come to focus on four principal racial-ethnic groups: White, African-

American or Black, Hispanic or Latino, and Asian and Pacific Islanders. For technical

and also political reasons, Hispanics have been treated by the U.S. Census Bureau as an

ethnic rather than a racial category. Respondents have been asked wither they hare

Hispanic separately from what racial group they belong to. Hispanics, in other words,

can be of any race. We have termed this classification method Hispanic categorical

dominance. (Meyers and J ames 2001). By convention and also political necessity,

researchers have essentially racialized the supposedly ethnic Hispanic category, by

treating Hispanics as a comparable category to those of Non-Hispanic Whites, and

Non-Hispanic Blacks In everyday life and ordinary speech, Hispanic or Latino is

used in the same sense as White or Black or Asian. Thus, we have dispensed with

the cumbersome pretense of the race versus ethnic distinction and refer hereafter only to

racial groups. Moreover, the 2000 Census famously allowed each respondent to

identify as a member of more than one race. There are many ways of classifying the

races now, thanks to the millions who have chosen more than one race. In this study, the

most important consideration was to classify races to be most compatible with the 1990

and earlier classification methods. The method used here is the Hispanic categorical

dominance with fractional apportionment of multiracials. All persons reporting

Hispanic identity are reserved for the Hispanic category. Then, persons reporting more

than one race are fractionally apportioned to the races they report. A person reporting

herself to be African American or Black and White is apportioned to Black and

to White. If she had reported Hispanic in addition to these racial categories, then

100% of her would have gone to the Hispanic category. Asians include, of course, a

Race Contours 2000 Resegregation of Los Angeles County, 1940-2000 5

great variety of race-ethnic identities, from Vietnamese to Chinese, Korean, and

J apanese. We cannot deal with the rationality of this system here, but again we are

following convention by treating Asians as a single category. We include as well Pacific

Islanders and Native Hawaiians in this category. Native Americans and all those

classified as other race, all totaling less than 1% of the Los Angeles County population,

have also been added to the Asian category, for reasons of compatibility with the 1940-

1990 data series.

Thus, for reasons of simplicity and common sense, Whites (in reality Euro-Americans)

are called Whites, Non-Hispanic African Americans are called Blacks; Hispanics

and Latinos are used interchangeably and Asians and Pacific Islanders are called

Asians.

2.3 Explanation of the Segregation Indices

For a complete discussion of the three main indices of segregation used in this study, see

Lieberson (1981), Massey and Denton (1988), White (1983), and White (1986). The

following is only a brief overview.

2.31 The Diversity Index

The Diversity Index ranges from 0 to about 1.4, and increases as the four racial groups

become more balanced within tracts, regardless of their proportion in the County as a

whole. The table below shows the Diversity Index and percentage racial populations for

five tracts in the year 2000: the least diverse, the 25

th

percentile, the median, the 75th

percentile, and the most diverse. Note that the actual population proportions for the

county as a whole in 2000 were 32% White; 9.7% Black, 44.6% Hispanic, and 13.7%

Asian.

Tract Diversity

Index

White Black Hispanic Asian Percentile

620003 0.00 100% 0% 0% 0% Lowest

541400 0.66 1% 26% 73% 1% 25

th

297000 0.87 69% 3% 21% 7% Median

311800 1.06 36% 3% 50% 10% 75

th

572201 1.37 24% 19% 25% 32% Highest

2.32 The Index of Dissimilarity

The Index of Dissimilarity, or ID,is the most commonly used measure of segregation in

American social science since the 1950s. Based always on a comparison of two groups (eg,

White vs. Nonwhites, Blacks vs. Nonblacks), this measure is very easy to interpret. The Index of

Dissimilarity ranges from 0 to 1 (or 0% to 100%), and tells us the percentage of a given

population that would have to change its residential location in order to even-out the distribution

of that groups across the metropolitan space. If Blacks were evenly settled across the entire

Race Contours 2000 Resegregation of Los Angeles County, 1940-2000 6

county, for example, their ID would be 0 (perfectly integrated). If Blacks only lived in census

tracts that were 100% Black, and no where else, then their ID score would be 1 (or 100% --

perfectly segregated). Scores of 70% or higher are considered to show serious segregation.

Blacks in U.S. cities have shown scores higher than this figure since the Second World War, and

yet in many western cities this figure has come down significantly. Here in Los Angeles the ID

for Blacks has decreased significantly from the very high 88% in 1960 and 1970 to the relatively

moderate 57% in 2000. Characterizing 57% as moderate is merely a relative judgment. It still

means that 57% of all Blacks would need to move their place of residence in order to achieve

perfectly even distribution across the county.

Although the ID is important and useful, at least because it is so widely used, it is also a rather

crude measure of segregation and needs to be supplemented with more nuanced measures. It is

totally insensitive to actual and relative group population sizes, for instance. For example, Blacks

in Los Angeles County might have the same ID score of, say, 57%, if there were only 10 Blacks

in the county, 1,000 Blacks, or 1,000,000. It only tells us how many Blacks would have to move

to even out the distribution, and it does not say anything about relative group sizes or their

relative location.

2.33 The Exposure Index

The Exposure Index is the central tool used to evaluate trends in segregation in this study.

The Exposure Index takes into account the relative sizes and locations of the various

groups in the county and calculates the probability (ranging from 0% to 100%) that

members of one group will have members of the other groups (or members of their own

group) as neighbors. The unit of analysis is the census tract, which is taken to represent

the neighborhood. The median tract population in Los Angeles County in 2000 was

4,461; the average was 4,633. The probability of exposure then, is that a person will

have a member of X group as a residential neighbor within their own census tract of

residence. The Exposure Index is a measure of residential segregation only. It does not

measure the exposure of groups to one another in the workplace or in public places

such as parks or shopping malls.

The most powerful feature of the Exposure Index is that it is asymmetric. For example,

Blacks in 1940 had a 45% chance of having White neighbors, but Whites only had a 1%

chance of having a Black neighbor. Why this asymmetry? Whites (at 2.6 million in

1940) vastly outnumbered Blacks (75,000 in that year) in Los Angeles County.

Moreover, the vast majority of Whites lived in segregated neighborhoods in which

Blacks were not permitted to live. Conversely a great many Whites lived in the

neighborhoods segregated for nonwhite residence (very few tracts were more than 50%

Black even in J im Crows heyday). Thus, by virtue of the specific locational and

proportional conditions of the county in 1940, Blacks were exposed to Whites much

more frequently than Whites were to Blacks, and a strong measure or segregation should

tell us this.

The very strength of the Exposure Indexthat it allows us to see the segregation

condition between more than one group at a time and from the different perspectives of

each of these groups, also leads to a confusing number of indexes: Between Blacks and

Race Contours 2000 Resegregation of Los Angeles County, 1940-2000 7

Hispanics, Hispanics and Blacks, Blacks and Asians, Asians and Blacks, Blacks and

Whites, Whites and Blacks, and so on. In order to manage this complexity and also to

make the greatest sense of the data, we have paired the charts displaying trends in the

Exposure Index by the two underlying perspectives implied by the asymmetric pairs.

We call these two perspectives Neighbors and Settlers.

Example: White Neighbors (Asks: what is the probability that Whites, Blacks,

Hispanics, and Asians will have White neighbors?)

Example: White Settlers (Asks: what is the probability that Whites will have

Whites, Blacks, Latinos, and Asians as neighbors?)

We have also taken care to explain our findings in straightforward, intuitive terms. Each

chart is accompanied with an explanation of the trends represented in it.

Whites

Blacks

Latinos Whites ?

Asians

Whites ?

Blacks ?

Whites

Latinos ?

Asians ?

Race Contours 2000 Resegregation of Los Angeles County, 1940-2000 8

3.0 Summary of Specific Findings:

Great differences in the historical and recent dynamics of each of the major racial

groups requires us to look at the question of segregation from each groups

perspective:

WHITES

Whites became less isolated from all other racial groups, but only relatively so.

Most of this desegregation is merely attributable to the simple decline in the

number and proportion of Whites in the county (from 81% in 1960 to 32% in

2000). Indeed, all four principal racial groups (Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, and

Asians) were less likely to have White neighbors.

While the Index of Diversity has steadily increased for the entire Los Angeles

County, the Index of Dissimilarity (the standard measure of segregation), has

remained constant for Whites since 1970, at exactly 57.

If Whites have any neighbors of color, they are most likely in 2000 to be Hispanic

(25% probability). Twenty-five percent is the greatest chance Whites have ever

faced of having a nonwhite neighbor. Whites had very little likelihood of having

a Black or Asian neighbor through 1970 (no greater than 2%), but this likelihood

increased only slightly by 2000. Whites have a 14% probability of having an

Asian neighbor; they still have only a 5% probability of having a Black neighbor.

Thus, from a White perspective, sharing neighborhoods with persons of color has

only advanced for the two groups whose population explosion since 1960 has

virtually forced this sharing.

As a rule, Whites have resegregated themselves as the county as a whole has

become hugely diverse. Simply by being outnumbered, the White population

only seems less spatially exclusive on the face of certain indices. Examination of

maps shows that the White population has retreated to the suburban fringe of the

metropolis, barricaded now behind the highest property values.

BLACKS

Blacks have seen a very different transformation than Whites. The probability

that blacks would have White neighbors actually fell steeply from 1940 through

1970, from 45% to 15%, and has stayed virtually constant ever since (hovering

between 17% and 18%. Blacks have far fewer White neighbors than they did two

generations ago, and no progress has been made since the nadir of the urban

crisis in 1970. Blacks have a slightly greater chance of having Asian neighbors

since 1970, but this figure is still only 9% in 2000. Most striking is that Blacks

are far more likely to have Hispanic neighbors. This probability shot up from

11% in 1970 to 41% in 2000. Like Whites, Blacks have been less and less likely

Race Contours 2000 Resegregation of Los Angeles County, 1940-2000 9

to have members of their own race as neighbors (since 1970), but the probability

that any other group would have Blacks as neighbors has stayed virtually constant

at less than 10% since 1940 (except for three decades, 1950-1970, when Asians

were slightly more likely to have Black neighbors).

Blacks remain the most segregated racial group in Los Angeles County, by any

measure. Like Whites, the movement of Blacks displays a retreat pattern in the

face of growing Hispanic and Asian populations. Moreover, the compactness of

the Black population seems to be reinforced by the voluntary self-segregation of

affluent Blacks, who may choose not to assert their relatively greater freedom to

settle in non-Black neighborhoods since the Civil Rights movement.

ASIANS AND HISPANICS

Asians and Hispanics, as new immigrants both differ from the experience of

Whites and Blacks, who are best classified as old immigrants. Both of these

groups have been less and less likely to have White neighbors, and more likely to

have only members of their own racial group as neighbors. But neither Asians

nor Hispanics are more likely to have Blacks as neighbors. Asians had a 16%

chance of having a Black neighbor in 1960, but only a 4% probability of that now.

For Hispanics, the figure has simply remained consistently low, ranging between

5% and 9% since 1940.

Both Hispanics and Asians are in a classic clustering enclave phase of

immigration, but unlike historic waves of European immigrants, their enclaves are

highly dispersed, and this sets the stage of much lower rates of segregation in the

future.

Race Contours 2000 Resegregation of Los Angeles County, 1940-2000 10

4.0 DETAILED FINDINGS

CHART 1: OVERALL POPULATION FIGURES

0

1,000,000

2,000,000

3,000,000

4,000,000

5,000,000

6,000,000

7,000,000

8,000,000

9,000,000

10,000,000

Tot al and Pr opor t ional Racial Populat ion of Los Angeles Count y, 1940-2000

Asian

Hispanic

Black

White

Asian 52,911 57,582 123,638 201,704 536,241 963,642 1,308,766

Hispanic 61,248 249,173 582,309 1,288,716 2,071,530 3,359,526 4,242,213

Black 75,206 214,897 459,806 755,719 924,774 931,449 924,518

White 2,620,450 3,796,190 4,897,580 4,798,872 3,977,480 3,647,555 3,043,840

1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000

1.9%

2.2%

2.7%

93.3%

1.3%

5.8%

5.0%

87.9%

2.0%

9.6%

7.6%

80.8%

2.9%

18.3%

10.7%

68.2%

7.1%

27.6%

12.3%

53.0%

10.8%

37.7%

10.5%

41.0%

13.7%

44.6%

9.7%

32.0%

Chart 1, Total and Proportional Racial Population of Los Angeles County, 1940-

2000, displays the total population, total subgroup population, and proportional share of

each population in percentages, from 1940 to 2000.

While the most obvious fact about the county is its great diversity, notice also that even by

1980, a most important feature of the overall patterns is that Whites reached the apogee of

their population size as early as 1960, and have been declining in absolute numbers ever

since.

The Black population peaked in 1990, but has remained almost constant since 1980, at just

under one million persons.

Indeed, despite spectacular growth of the Los Angels metropolis since 1940, Whites in 2000

are only slightly more numerous than they were in before the Second World War.

In other words, the growth of Los Angeles County since 1960 is almost entirely the work of

non-White and non-Black groups.

Race Contours 2000 Resegregation of Los Angeles County, 1940-2000 11

CHART 2: DIVERSITY INDEX

Diver sit y Index: Los Angeles Count y, 1940-2000

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

Diversity Index

Diversity Index 0.22 0.23 0.38 0.54 0.73 0.82 0.84

1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000

Chart 2: Diversity Index: Los Angeles County, 1940-2000, is a very important

measure of the increasing balance of the Countys four principal racial groups since 1940.

In 1990, it was not clear if the Diversity Index was beginning to flatten-out, but the 2000

data clearly show that it is. Los Angeles County may be stabilizing in the extent of its

diversity.

This graph of the sharply increasing Diversity Index can be very misleading, however. It

seems to suggest that the Metropolis is becoming a multiracial borderland, wherein the

races mix freely. Such is not at all the case, as the following Charts will make clear.

Race Contours 2000 Resegregation of Los Angeles County, 1940-2000 12

CHART 3: INDEX OF DISSIMILARITY

Chart 3: Index of Dissimilarity for Whites, Blacks, Hispanics and Asians

in Los Angeles County, 1940-2000, displays the most commonly used measure of segregation in

American social science since the 1950s. Based always on a comparison of two groups (eg, White vs.

Nonwhites, Blacks vs. Nonblacks), this measure is very easy to interpret. The Index of Dissimilarity

or ID ranges from 0 to 1, and tells us the percentage of a given population that would have to

change its residential location in order to even-out the distribution of that groups across the

metropolitan space. If Blacks were evenly settled across the entire county, for example, their ID

would be 0 (perfectly integrated). If Blacks only lived in census tracts that were 100% Black, and no

where else, then their ID score would be 1 (perfectly segregated).

Scores of 70% or higher are considered to show serious segregation. Blacks in U.S. cities have

shown scores higher than this figure since the Second World War, and yet in many western cities this

figure has come down significantly. Here in Los Angeles the ID for Blacks has decreased

significantly from the very high 88% in 1960 and 1970 to the relatively moderate 57% in 2000.

J ust as remarkable, however, is how little the ID for Whites has changed: almost not at all since 1960.

The figure has remained frozen at 57 or 56 since 1970, which is precisely the same in 2000 as the ID

for Blacks. In other words, the ID also shows us that Whites and Blacks are equally segregated, and

that most members of each group would need to move to achieve integration.

The ID scores for Hispanics and Asians are also significant. Hispanics are the least segregated racial

group by this measure. Less than half of all Hispanics would need to move in order to achieve full

spatial integration. Their score fell from 1950 to 1980, but is clearly on the rise again.

Asians are only moderately segregated, and have remained at the same level of segregations by the ID

measure since 1980. About half would need to move to even out the spatial distribution in the county.

Index of Dissimilarity for Whites, Blacks, Hispanics and Asians

in Los Angeles County, 1940-2000

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

Blacks

Whites

Asians

Hispanics

Blacks 0.82 0.82 0.88 0.88 0.76 0.64 0.57

Whites 0.62 0.71 0.64 0.57 0.57 0.57 0.56

Asians 0.57 0.7 0.5 0.44 0.51 0.5 0.51

Hispanics 0.58 0.85 0.56 0.48 0.36 0.41 0.43

1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000

Race Contours 2000 Resegregation of Los Angeles County, 1940-2000 13

CHART 4a: WHITE NEIGHBORS

Chart 4a, Probability that Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians in Los Angeles County will

have White Neighbors, 1940-2000, uses a much more powerful and revealing measure or

segregation than the Index of Dissimilarity. The measure used in Charts 4a through 7b is the

Exposure Index, which measures the probability that members of one group will have neighbors of

any other group. It ranges from 0 to 1. Unlike the relatively crude Index of Dissimilarity, the

Exposure Index takes into account the relative size of different groups, and is capable of measuring

the segregation conditions between multiple racial groups simultaneously. In order to make these

patterns as clear as possible, we present them in pairs, each pair exploring the experience of each of

the four principal racial groups.

Chart 4a tells us the probability that Whites, Blacks, Hispanics and Asians will have White neighbors.

The probability that Whites will have white neighbors is a measure of their isolation, and we see

here that Whites have become less and less likely to have White neighbors. On the face of it, this

seems like clear evidence of desegregation. But that is not the case. Notice that all racial groups have

been less and less likely to have White neighbors since 1940! Indeed, Asians, Hispanics and Blacks in

2000 had less than a 24% chance of sharing their neighborhoods with Whites.

Blacks have been no more likely to have White neighbors in all the years since 1960.

The simple fact explaining the patterns in Chart 4a is that Whites are only seeming to be less

isolated because they are grossly outnumbered, and some greater level of exposure to other

racial groups is inevitable as the length of the perimeter, or circumference, around the

segregated core of the metropolis continues to grow. Chart 4b will better clarify this

situation.

Pr obabilit y t hat Whit es, Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians

in Los Angeles Count y will have Whit e Neighbor s, 1940-2000

0.00

0.10

0.20

0.30

0.40

0.50

0.60

0.70

0.80

0.90

1.00

Whites with Whites

Asians with Whites

Hispanics with Whites

Blacks with Whites

Whites with Whites 0.95 0.94 0.90 0.81 0.72 0.64 0.57

Asians with Whites 0.77 0.63 0.57 0.53 0.49 0.39 0.23

Hispanics with Whites 0.82 0.55 0.58 0.52 0.34 0.23 0.18

Blacks with Whites 0.45 0.32 0.22 0.15 0.17 0.18 0.17

1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000

Race Contours 2000 Resegregation of Los Angeles County, 1940-2000 14

Chart 4b: WHITE SETTLERS

Chart 4b, Probability that Whites will have Black, Hispanic, or Asian Neighbors

in Los Angeles County, 1940-2000, looks at the White residential experience from the other direction as that

shown in 4a. The Exposure Index is asymmetric, which means that we can see the segregation relation from

two different perspectives for each pair of racial groups. Since the groups are all very different in size and

location, these figures are not simple the inverse, but reveal the less obvious conditions of segregation that are

a function of location. Thus, for example, looking back at Chart 4a, we see that Blacks had a 45% chance of

having White neighbors in 1940, but here in Chart 4b we see that Whites in that same year had only a 1%

chance of having a Black neighbor. This asymmetry can easily be explained by the fact that Blacks were

vastly outnumbered in 1940, and because most Black neighborhoods had significant White populations as well

(which is no longer the case: Whites have almost completely removed themselves from Black neighborhoods).

The hard fact is that this severe level of segregation has not changed significantly in 60 years of struggles

against the White-Black divide. White families in Los Angeles County in 2000 still had only a 5% chance of

sharing their neighborhood with African American families.

Whites are significantly more likely to have Hispanic neighbors, 25% in 2000 compared with 14% in 1970.

But again, this figure is easy to explain by rapid increase in the Hispanic population and the steady decrease of

the White population. The Hispanic population has grown around many clusters of settlement in the County,

and so the edges between Hispanic and White areas have grown in length, making increasing exposure

more likely. To put this figure in perspective, we must again refer back to Chart 4a: Hispanics are less likely

to have Whites as neighbors (18%), and this figure has been steadily declining.

Whites are only in the year 2000 significantly likely to have Asian neighbors (14%), but again, Chart 4a

shows that as Asians grow in population size, they are less likely to have White neighbors (down to 23% in

2000 from 49% in 1980).

Pr obabilit y t hat Whit es will have Black, Hispanic, or Asian Neighbor s

in Los Angeles Count y, 1940-2000

0.00

0.05

0.10

0.15

0.20

0.25

0.30

Whites with Hispanics

Whites with Asians

Whites with Blacks

Whites with Hispanics 0.02 0.04 0.07 0.14 0.18 0.22 0.25

Whites with Asians 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.07 0.1 0.14

Whites with Blacks 0.01 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.04 0.05 0.05

1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000

Race Contours 2000 Resegregation of Los Angeles County, 1940-2000 15

Chart 5a: BLACK NEIGHBORS

Chart 5a, Probability that Blacks, Whites, Hispanics, and Asians will have Black

Neighbors in Los Angeles County, 1940-2000, Shows first of all that Whites,

Hispanics, and Asians are very unlikely to have Black neighbors in 2000. Indeed, Whites

and Hispanics are no more likely to have Black neighbors than they were in 1940 (or

insignificantly so).

The second most striking pattern in Chart 5a is that Blacks become increasingly isolated

from other groups (more likely to have only other Blacks as neighbors), from 1940 though

1970, and then that trend reverses. In 1970, Blacks had a 72% of having black neighbors,

but by 2000, Blacks had only a 34% chance of having a Black neighbor.

How is this second finding consistent with the first finding: that other groups re very

unlikely to have Black neighbors? Looking at Chart 5b explains what is happening.

Pr obabilit y t hat Blacks, Whit es, Hispanics, and Asians

will have Black Neighbor s in Los Angeles Count y, 1940-2000

0.00

0.10

0.20

0.30

0.40

0.50

0.60

0.70

0.80

Blacks with Blacks

Hispanics with Blacks

Asians with Blacks

Whites with Blacks

Blacks with Blacks 0.46 0.55 0.64 0.72 0.60 0.42 0.34

Hispanics with Blacks 0.05 0.08 0.08 0.06 0.08 0.09 0.09

Asians with Blacks 0.06 0.14 0.16 0.11 0.08 0.06 0.04

Whites with Blacks 0.01 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.04 0.05 0.05

1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000

Race Contours 2000 Resegregation of Los Angeles County, 1940-2000 16

Chart 5b BLACK SETTLERS

Chart 5b, Probability that Blacks will have White, Hispanic, or Asian Neighbors

in Los Angeles County, 1940-2000, shows that the reason for Blacks decreasing

isolation is an increased sharing of neighborhood space with Hispanics, the most dynamic

and rapidly expanding racial group in the metropolis.

Blacks are no more likely to have Whites as neighbors than they were at the peak of their

isolation, in 1970. This probability has

And Blacks are still quite unlikely to have Asian neighbors, a rate which has increased

from a mere 4% from 1940 through 1980 to 9% in 2000.

This chart points up the very serious question of Black-Hispanic territorial transitions.

The time-series maps show high levels of displacement of Blacks by Hispanics since the

1960s.

Pr obabilit y t hat Blacks will have Whit e, Hispanic, or Asian Neighbor s

in Los Angeles Count y, 1940-2000

0.00

0.05

0.10

0.15

0.20

0.25

0.30

0.35

0.40

0.45

0.50

Blacks with Whites

Blacks with Hispanics

Blacks with Asians

Blacks with Whites 0.45 0.32 0.22 0.15 0.17 0.18 0.17

Blacks with Hispanics 0.04 0.09 0.10 0.11 0.19 0.34 0.41

Blacks with Asians 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.03 0.04 0.06 0.09

1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000

Race Contours 2000 Resegregation of Los Angeles County, 1940-2000 17

Charts 6a HISPANIC NEIGHBORS

Chart 6a, Probability that Hispanics, Blacks, Whites, and Asians will have Hispanic

Neighbors in Los Angeles County, 1940-2000, shows first of all that all groups have

been increasingly likely to have Hispanic neighbors since 1940.

The most dramatic increase has been in the isolation of Hispanics. By 2000 Hispanics were

63% likely to have only other Hispanic neighbors.

Next most dramatic has been the increase in likelihood that Blacks will have Hispanic

neighbors, a pattern we already explored in Table 5b. However, here we can see that

Blacks have increased their exposure to Hispanics at a higher rate and at greater levels that

either Whites or Asians.

Whites and Asians have the lowest probability of sharing neighborhoods with Hispanics,

and the score for Asians has actually decreased since 1990, from 32% to 24%.

Bear in mind, however, that the Hispanic Neighbors perspective is looking at Hispanics

from the outside in. Table 6b shows what Hispanics see from the inside of their

community looking out at Whites, Blacks, and Asians. The story is very different.

Probability that Hispanics, Blacks, Whites, and Asians

will have Hispanic Neighbors in Los Angeles County, 1940-2000

0.00

0.10

0.20

0.30

0.40

0.50

0.60

0.70

Hispanics with Hispanics

Blacks with Hispanics

Asians with Hispanics

Whites with Hispanics

Hispanics with Hispanics 0.09 0.34 0.31 0.38 0.50 0.58 0.63

Blacks with Hispanics 0.04 0.09 0.10 0.11 0.19 0.34 0.41

Asians with Hispanics 0.05 0.15 0.16 0.24 0.27 0.32 0.24

Whites with Hispanics 0.02 0.04 0.07 0.14 0.18 0.22 0.25

1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000

Race Contours 2000 Resegregation of Los Angeles County, 1940-2000 18

Chart 6a HISPANIC SETTLERS

Table 6b, Probability that Hispanics will have Black, White, or Asian Neighbors in

Los Angeles County, 1940-2000, tells a very striking story. Hispanics are increasingly

unlikely to have non-Hispanic neighbors.

The steepest decline has been in the chances Hispanics have of sharing neighborhoods with

Whites. This was a very high 82% in 1940 and has plummeted ever since, to only 18% in

2000.

J ust as striking is that Hispanics have never had much exposure to Blacks or Asians as

neighbors. These figures have remained almost flat at less than 10% since 1940.

Pr obabilit y t hat Hispanics will have Black, Whit e, or Asian

Neighbor s in Los Angeles Count y, 1940-2000

0.00

0.10

0.20

0.30

0.40

0.50

0.60

0.70

0.80

0.90

Hispanics with Whites

Hispanics with Blacks

Hispanics with Asians

Hispanics with Whites 0.82 0.55 0.58 0.52 0.34 0.23 0.18

Hispanics with Blacks 0.05 0.08 0.08 0.06 0.08 0.09 0.09

Hispanics with Asians 0.04 0.03 0.03 0.04 0.07 0.09 0.10

1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000

Race Contours 2000 Resegregation of Los Angeles County, 1940-2000 19

Chart 7a: ASIAN NEIGHBORS

Chart 7a, Probability that Asians, Blacks, Whites, and Hispanics will have Asian

Neighbors in Los Angeles County, 1940-2000, shows modest increases that all groups will

have Asian neighborsbut most of all that Asians are more likely to have Asian neighbors.

Even so , it is very important to note that the rates a quite low. This chart is scaled to reach its

maximum at 25%, so the values in it a quite small despite the visual effect of the rising lines.

The bottom line is that Whites, Blacks, and Asians in 2000 still had no more than a 14%

chance of having an Asian neighbor.

The Asian population has bee rising more slowly than the Hispanic, to compare the two main

immigrant groups, but its volume has now surpassed the one million mark, so we would

expect that the non-Asian groups will be more likely to have Asian neighbors. The relatively

low figures here, however, suggest that Asians are settling in clustered enclaves, a prediction

supported by the companion Table 7b.

Pr obabilit y t hat Asians, Blacks, Whit es, and Hispanics

will have Asian Neighbor s in Los Angeles Count y, 1940-2000

0.00

0.05

0.10

0.15

0.20

0.25

Asians with Asians

Whites with Asians

Hispanics with Asians

Blacks with Asians

Asians with Asians 0.12 0.07 0.11 0.12 0.15 0.22 0.20

Whites with Asians 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.07 0.1 0.14

Hispanics with Asians 0.04 0.03 0.03 0.04 0.07 0.09 0.10

Blacks with Asians 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.03 0.04 0.06 0.09

1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000

Race Contours 2000 Resegregation of Los Angeles County, 1940-2000 20

Chart 7a: ASIAN SETTLERS

Chart 7b, Probability that Asians will have White, Hispanic, or Black Neighbors

in Los Angeles County, 1940-2000 reinforces all the trends we have seen in the

previous tables.

Asians are less and less likely to have White neighbors. This figure has dropped from

77% in 1940 to 39% in 1990 and 23% in 2000.

Asians were increasingly likely to have Hispanic neighbors until 1990, but this figure had

begun to drop as well, to 24%.

Asians were never very likely to have Black neighbors, and this has steadily decreased

since 1960, to a mere 4% in 2000.

Pr obabilit y t hat Asians will have Whit e, Hispanic, or Black Neighbor s

in Los Angeles Count y, 1940-2000

0.00

0.10

0.20

0.30

0.40

0.50

0.60

0.70

0.80

0.90

Asians with Whites

Asians with Hispanics

Asians with Blacks

Asians with Whites 0.77 0.63 0.57 0.53 0.49 0.39 0.23

Asians with Hispanics 0.05 0.15 0.16 0.24 0.27 0.32 0.24

Asians with Blacks 0.06 0.14 0.16 0.11 0.08 0.06 0.04

1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000

Race Contours 2000 Resegregation of Los Angeles County, 1940-2000 21

Race Contours 2000 Resegregation of Los Angeles County, 1940-2000 22

Bibliography: Works Cited

Ethington, Philip J . 2000. "Segregated Diversity: Race-Ethnicity, Space, and Political

Fragmentation in Los Angeles County, 1940-1994," Final Report submitted to the J ohn

Randolph Haynes and Dora Haynes Foundation (20 J uly 2000).

http://www.usc.edu/dept/LAS/history/historylab/Haynes_FR/index.html

Frey, William H., and Ethington, Philip J . 2001. Diversity and Segregation of

Municipal Places in Los Angeles County, 1990-2000 Race Contours 2000 Project,

Public Research Report 2001-06

[http://www.usc.edu/schools/sppd/research/race_census/research_reports/research_reports.htm]

Lieberson, Stanley 1981 An Asymmetrical Approach to Segregation, in Ethnic

Segregation in Cities, edited by Ceri Peach, Vaughn Robinson an Susan Smith (Athens,

GA: The University of Georgia Press, 1981): 61-82.

Massey, Douglas S. and Denton, Nancy A. 1988 The Dimensions of Residential

Segregation, Social Forces 67:2 (December): 281-315.

Myers, Dowell and J ames, Angela 2001 Overlap: A User Guide to Race and

Hispanic Origin in Census 2000," Race Contours 2000 Project, Public Research Report

2001-01 [http://www.usc.edu/schools/sppd/research/race_census/research_reports/research_reports.htm]

Myers, Dowell, and Park, J ulie. 2001 Racially Balanced Cities in Southern California,

1980-2000. Race Contours 2000 Project, Public Research Report 2001-05

[http://www.usc.edu/schools/sppd/research/race_census/research_reports/research_reports.htm]

White, Michael J . "The Measurement of Spatial Segregation," American J ournal of

Sociology 88:5 (March 1983): 1008-1018.

White, Michael J . Segregation and Diversity Measures in Population Distribution,

Population Index. 52 (1986): 198-221.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- La Nueva California: Latinos from Pioneers to Post-MillennialsDa EverandLa Nueva California: Latinos from Pioneers to Post-MillennialsNessuna valutazione finora

- The New Metro MinorityDocumento18 pagineThe New Metro MinorityteembillNessuna valutazione finora

- Reinventing The Color LineDocumento27 pagineReinventing The Color Linemongo_beti471Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Professional Geographer: To Cite This Article: Christopher Lukinbeal, Patricia L. Price & Cayla Buell (2012)Documento18 pagineThe Professional Geographer: To Cite This Article: Christopher Lukinbeal, Patricia L. Price & Cayla Buell (2012)dragon_287Nessuna valutazione finora

- Latinos in New York: Communities in TransitionDa EverandLatinos in New York: Communities in TransitionSherrie BaverNessuna valutazione finora

- Racial and Ethnic Diversity Goes Local: Charting Change in American Communities Over Three DecadesDocumento26 pagineRacial and Ethnic Diversity Goes Local: Charting Change in American Communities Over Three DecadesRussell Sage FoundationNessuna valutazione finora

- Diversity's Child: People of Color and the Politics of IdentityDa EverandDiversity's Child: People of Color and the Politics of IdentityNessuna valutazione finora

- Draft 13. Social and Cultural Geography 4.09Documento39 pagineDraft 13. Social and Cultural Geography 4.09Pilar Andrea González QuirozNessuna valutazione finora

- Black and Brown in Los Angeles: Beyond Conflict and CoalitionDa EverandBlack and Brown in Los Angeles: Beyond Conflict and CoalitionNessuna valutazione finora

- Diversity HighlightsDocumento2 pagineDiversity HighlightsvilmasilvabutymNessuna valutazione finora

- Ethnic Americans: Immigration and American SocietyDa EverandEthnic Americans: Immigration and American SocietyNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction: Asian American Suburban HistoryDocumento13 pagineIntroduction: Asian American Suburban HistoryBecky NicolaidesNessuna valutazione finora

- A Nation of Descendants: Politics and the Practice of Genealogy in U.S. HistoryDa EverandA Nation of Descendants: Politics and the Practice of Genealogy in U.S. HistoryNessuna valutazione finora

- Diversity Paradox - Chapter 1Documento20 pagineDiversity Paradox - Chapter 1Russell Sage FoundationNessuna valutazione finora

- Immigration and the Border: Politics and Policy in the New Latino CenturyDa EverandImmigration and the Border: Politics and Policy in the New Latino CenturyNessuna valutazione finora

- A Pivotal Decade For America's White and Minority PopulationsDocumento2 pagineA Pivotal Decade For America's White and Minority PopulationsUrbanYouthJusticeNessuna valutazione finora

- The Black Image in the White Mind: Media and Race in AmericaDa EverandThe Black Image in the White Mind: Media and Race in AmericaNessuna valutazione finora

- Davis M - Magical Urbanism - Latinos Reinvent The US Big CityDocumento41 pagineDavis M - Magical Urbanism - Latinos Reinvent The US Big CityzvonomirNessuna valutazione finora

- In Search of the Mexican Beverly Hills: Latino Suburbanization in Postwar Los AngelesDa EverandIn Search of the Mexican Beverly Hills: Latino Suburbanization in Postwar Los AngelesNessuna valutazione finora

- Bonilla SilvaDocumento14 pagineBonilla SilvaurayoannoelNessuna valutazione finora

- The New Latino Studies Reader: A Twenty-First-Century PerspectiveDa EverandThe New Latino Studies Reader: A Twenty-First-Century PerspectiveValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- White Racial Ethni Identity Usa PDFDocumento18 pagineWhite Racial Ethni Identity Usa PDFEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- Race and EthnicityDocumento27 pagineRace and EthnicityAnarghyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Artificial StatesDocumento40 pagineArtificial Statesvidovdan9852Nessuna valutazione finora

- Excerpt From "Latino America" by Matt Marreto and Gary Segura.Documento10 pagineExcerpt From "Latino America" by Matt Marreto and Gary Segura.OnPointRadioNessuna valutazione finora

- Lees. Gentrification, Race and EthnicityDocumento7 pagineLees. Gentrification, Race and EthnicityHarpoZgzNessuna valutazione finora

- Jewish Demographic Studies in The Context of The Census of CanadaDocumento20 pagineJewish Demographic Studies in The Context of The Census of CanadaIrina NemteanuNessuna valutazione finora

- Soto Marquez 2018 I M Not Spanish I M From Spain Spaniards Bifurcated Ethnicity and The Boundaries of Whiteness andDocumento15 pagineSoto Marquez 2018 I M Not Spanish I M From Spain Spaniards Bifurcated Ethnicity and The Boundaries of Whiteness andSebastián MurilloNessuna valutazione finora

- Celebrating The Legacy, Embracing The Future: A Neighborhood Study For Second Baptist ChurchDocumento28 pagineCelebrating The Legacy, Embracing The Future: A Neighborhood Study For Second Baptist ChurchProgram for Environmental And Regional Equity / Center for the Study of Immigrant IntegrationNessuna valutazione finora

- Magical Urbanism Latinos Reinvent The US B - Mike DavisDocumento41 pagineMagical Urbanism Latinos Reinvent The US B - Mike DaviskeithholdichNessuna valutazione finora

- Movimientos Politicos AfroecuatorianosDocumento154 pagineMovimientos Politicos AfroecuatorianosProfe ViníciusNessuna valutazione finora

- Deborah Philips - 2007Documento22 pagineDeborah Philips - 2007Joana Catarina São Lazaro InácioNessuna valutazione finora

- Name: DateDocumento3 pagineName: DatewtlodgeNessuna valutazione finora

- Defining Race, Ethnicity, and Related ConstructsDocumento29 pagineDefining Race, Ethnicity, and Related ConstructsAria JennaNessuna valutazione finora

- MacoDocumento56 pagineMacotropNessuna valutazione finora

- Casanova Organizing IdentitiesDocumento22 pagineCasanova Organizing IdentitiesDemdexopNessuna valutazione finora

- Wage Trends Among Disadvantaged Minorities: National Poverty Center Working Paper SeriesDocumento41 pagineWage Trends Among Disadvantaged Minorities: National Poverty Center Working Paper SeriesJonNessuna valutazione finora

- La Times 2003Documento2 pagineLa Times 2003Geoffrey FoxNessuna valutazione finora

- Steven Gregory, Race, Rubbish, and ResistanceDocumento25 pagineSteven Gregory, Race, Rubbish, and ResistanceGulbana CekenNessuna valutazione finora

- Dissertation La Population Des Etats-UnisDocumento5 pagineDissertation La Population Des Etats-Unisalrasexlie1986100% (1)

- Segregation and StratificationDocumento19 pagineSegregation and StratificationJorge RoshNessuna valutazione finora

- District of Columbia State Data Center Monthly Brief: December 2011Documento4 pagineDistrict of Columbia State Data Center Monthly Brief: December 2011CARECENNessuna valutazione finora

- Racism & Capitalism. Chapter 1: Racism Today - Iggy KimDocumento5 pagineRacism & Capitalism. Chapter 1: Racism Today - Iggy KimIggy KimNessuna valutazione finora

- Hispanic ResearchDocumento25 pagineHispanic ResearchZacharyNessuna valutazione finora

- Kaufmann, EP, 'Multiculturalism,' Chapter in Singh, Robert (Ed.), Governing America: The Politics of A Divided Democracy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), Pp. 449-66Documento53 pagineKaufmann, EP, 'Multiculturalism,' Chapter in Singh, Robert (Ed.), Governing America: The Politics of A Divided Democracy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), Pp. 449-66Eric KaufmannNessuna valutazione finora

- Latino Politics-Oboler PDFDocumento17 pagineLatino Politics-Oboler PDFStephanieKochNessuna valutazione finora

- The Colors of Nature - Essays Edited by Alison H. Deming and Lauret E. SavoyDocumento17 pagineThe Colors of Nature - Essays Edited by Alison H. Deming and Lauret E. SavoyMilkweed Editions25% (4)

- The Origins of African American Family Structure by Steven RugglesDocumento16 pagineThe Origins of African American Family Structure by Steven Rugglessahmadouk7715Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ethnicity & Urban Geography: Professor Baylis Week 7, MondayDocumento47 pagineEthnicity & Urban Geography: Professor Baylis Week 7, Mondayvictorbernal7749Nessuna valutazione finora

- Urban DictionaryDocumento22 pagineUrban DictionaryMarty MahNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 10Documento56 pagineChapter 10Calvin Klien Pope100% (3)

- Whiteness in Latin America As Seen Through Official Statistics (1870-1930)Documento57 pagineWhiteness in Latin America As Seen Through Official Statistics (1870-1930)Fernando UrreaNessuna valutazione finora

- Stolzenberg Ethnicity Geography and OccupationalDocumento13 pagineStolzenberg Ethnicity Geography and OccupationalRoss M StolzenbergNessuna valutazione finora

- State of White America 2007Documento108 pagineState of White America 2007Jack and friend100% (1)

- Cultural Landscape An Introduction To Human Geography 11th Edition Rubenstein Solutions ManualDocumento16 pagineCultural Landscape An Introduction To Human Geography 11th Edition Rubenstein Solutions Manualcommenceingestah7nxd9100% (27)

- The Place Immigration in Studies of Geography and RaceDocumento14 pagineThe Place Immigration in Studies of Geography and RaceMohammad Nick KhooNessuna valutazione finora

- Gay AJPS 2006Documento17 pagineGay AJPS 2006Nick_Davis_8873Nessuna valutazione finora

- Afro Latin American StudiesDocumento24 pagineAfro Latin American StudiesAlessandra PraunNessuna valutazione finora

- (Final) Stakeholder PaperDocumento13 pagine(Final) Stakeholder PaperIzzy MannixNessuna valutazione finora

- Bail AssignmentDocumento7 pagineBail AssignmentIzzy MannixNessuna valutazione finora

- C2017C00184Documento238 pagineC2017C00184Izzy MannixNessuna valutazione finora

- Addressing Xenophobia in Young PeopleDocumento36 pagineAddressing Xenophobia in Young PeopleIzzy MannixNessuna valutazione finora

- GH - Essay 1Documento7 pagineGH - Essay 1Izzy MannixNessuna valutazione finora

- Caron Simply Soft Christmas Tree SkirtDocumento3 pagineCaron Simply Soft Christmas Tree SkirtIzzy MannixNessuna valutazione finora

- Olivier EvDocumento3 pagineOlivier EvIzzy MannixNessuna valutazione finora

- Black PowerDocumento12 pagineBlack PowerIzzy MannixNessuna valutazione finora

- This Boy's Life Essay2 DraftDocumento2 pagineThis Boy's Life Essay2 DraftIzzy MannixNessuna valutazione finora

- Writing Successful Research Paper Wi11 Mmw5Documento53 pagineWriting Successful Research Paper Wi11 Mmw5Izzy MannixNessuna valutazione finora

- This Boy's Life Essay1 DraftDocumento2 pagineThis Boy's Life Essay1 DraftIzzy MannixNessuna valutazione finora

- China - Town (1974) : Film Criteria ExplanationDocumento2 pagineChina - Town (1974) : Film Criteria ExplanationIzzy MannixNessuna valutazione finora

- Geography and Physical CharacteristicsDocumento2 pagineGeography and Physical CharacteristicsIzzy MannixNessuna valutazione finora

- Freddie Mercury WordDocumento6 pagineFreddie Mercury WordIzzy MannixNessuna valutazione finora

- L.A. Noir Gary J. Hausladen and Paul F. StarrsDocumento28 pagineL.A. Noir Gary J. Hausladen and Paul F. StarrsIzzy MannixNessuna valutazione finora

- Proposed Changes To The Racial Discrimination ActDocumento2 pagineProposed Changes To The Racial Discrimination ActIzzy MannixNessuna valutazione finora

- 2005 Cronulla Riots - Media Research Activity 1Documento3 pagine2005 Cronulla Riots - Media Research Activity 1Izzy MannixNessuna valutazione finora

- Arts Degrees in Victoria 2013Documento4 pagineArts Degrees in Victoria 2013Izzy MannixNessuna valutazione finora

- Son of Noir: Neo-Film Noir and Neo-B Picture, Alain SilverDocumento8 pagineSon of Noir: Neo-Film Noir and Neo-B Picture, Alain SilverIzzy MannixNessuna valutazione finora

- Mark Baker's The VillageDocumento2 pagineMark Baker's The VillageIzzy Mannix100% (2)

- L.A. Noir Gary J. Hausladen and Paul F. StarrsDocumento28 pagineL.A. Noir Gary J. Hausladen and Paul F. StarrsIzzy MannixNessuna valutazione finora

- Immigration Firm Gives Back To Undocumented Essential WorkersDocumento3 pagineImmigration Firm Gives Back To Undocumented Essential WorkersHerman Legal Group, LLCNessuna valutazione finora

- Account Acceptance NoticeDocumento1 paginaAccount Acceptance NoticeOSBALDO DAMIAN GOMEZ VILLELANessuna valutazione finora

- Thailand AdoptionDocumento3 pagineThailand AdoptionkatuengganNessuna valutazione finora

- Eeo-410-Assignment-2-Poster 1Documento2 pagineEeo-410-Assignment-2-Poster 1api-313252438Nessuna valutazione finora

- David Bier - E-Verify Mandate Is Costly For Businesses and WorkersDocumento4 pagineDavid Bier - E-Verify Mandate Is Costly For Businesses and WorkersCompetitive Enterprise InstituteNessuna valutazione finora

- Tung Chin Hui V RodriguezDocumento3 pagineTung Chin Hui V RodriguezZepht BadillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Visa Pricing Currency Table: Indonesian Rupiah (IDR)Documento14 pagineVisa Pricing Currency Table: Indonesian Rupiah (IDR)Alex MNessuna valutazione finora

- Maquiling v. COMelec Digest PDFDocumento2 pagineMaquiling v. COMelec Digest PDFCarla Mapalo71% (7)

- India E-Visa Draft FormDocumento4 pagineIndia E-Visa Draft FormPrecy CoNessuna valutazione finora

- Exercitii Cu Fraze ConditionaleDocumento2 pagineExercitii Cu Fraze ConditionaleStefania BaciuNessuna valutazione finora

- Imm5813 2-Yo0wekoDocumento2 pagineImm5813 2-Yo0wekoGaurav PradhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Model Minority - Yellow Peril PDFDocumento27 pagineModel Minority - Yellow Peril PDFnipi80Nessuna valutazione finora

- The World of Our GrandmothersDocumento4 pagineThe World of Our GrandmothersMorize Arenal100% (1)

- April 2009: BC ObserverDocumento11 pagineApril 2009: BC ObserverbcobserverNessuna valutazione finora

- Tourist/Business Visa Requirements For Housewives (For Mama)Documento2 pagineTourist/Business Visa Requirements For Housewives (For Mama)Apple Ke-eNessuna valutazione finora

- Fluid Mechanics 6th Edition Kundu, Cohen, Dowling Solutions ManualDocumento5 pagineFluid Mechanics 6th Edition Kundu, Cohen, Dowling Solutions Manualanie0% (3)

- Imm5825 2-15XFPLJWDocumento2 pagineImm5825 2-15XFPLJWHabibNessuna valutazione finora

- Sec. of Justice v. Koruga - Golden RuleDocumento13 pagineSec. of Justice v. Koruga - Golden RulebrownboomerangNessuna valutazione finora

- Documents Required For Non-ECRDocumento3 pagineDocuments Required For Non-ECRmep.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Annexure DDocumento1 paginaAnnexure Dambadi.ma1955Nessuna valutazione finora

- Document Checklist For Working Visa in NepalDocumento2 pagineDocument Checklist For Working Visa in NepalSSNessuna valutazione finora

- c1 Listening Skills and Vocabulary DevelopmentDocumento2 paginec1 Listening Skills and Vocabulary DevelopmentLara María RamosNessuna valutazione finora

- Hyd To DelhiDocumento1 paginaHyd To Delhichinmay hawaleNessuna valutazione finora

- ATD Symposium ProgramDocumento2 pagineATD Symposium ProgramFox NewsNessuna valutazione finora

- Mi Jung Kim, A098 768 574 (BIA Sept. 19, 2014)Documento10 pagineMi Jung Kim, A098 768 574 (BIA Sept. 19, 2014)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNessuna valutazione finora

- E VisaDocumento2 pagineE VisaPrabha KaranNessuna valutazione finora

- 7003-Documents Required For Non-ECRDocumento3 pagine7003-Documents Required For Non-ECR108databoxNessuna valutazione finora

- H1B Visa Job Interview Questions and AnswersDocumento4 pagineH1B Visa Job Interview Questions and AnswersEphrem zenebe100% (1)

- Uxbridge College Application FormDocumento2 pagineUxbridge College Application FormM Faisal ChNessuna valutazione finora

- I 864Documento8 pagineI 864Loraine AlcazarNessuna valutazione finora

- Unwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to CampusDa EverandUnwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to CampusValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (22)

- Decolonizing Wellness: A QTBIPOC-Centered Guide to Escape the Diet Trap, Heal Your Self-Image, and Achieve Body LiberationDa EverandDecolonizing Wellness: A QTBIPOC-Centered Guide to Escape the Diet Trap, Heal Your Self-Image, and Achieve Body LiberationValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (22)

- The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and LoveDa EverandThe Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and LoveValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (384)

- The Masonic Myth: Unlocking the Truth About the Symbols, the Secret Rites, and the History of FreemasonryDa EverandThe Masonic Myth: Unlocking the Truth About the Symbols, the Secret Rites, and the History of FreemasonryValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (14)

- Never Chase Men Again: 38 Dating Secrets to Get the Guy, Keep Him Interested, and Prevent Dead-End RelationshipsDa EverandNever Chase Men Again: 38 Dating Secrets to Get the Guy, Keep Him Interested, and Prevent Dead-End RelationshipsValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (387)

- Lucky Child: A Daughter of Cambodia Reunites with the Sister She Left BehindDa EverandLucky Child: A Daughter of Cambodia Reunites with the Sister She Left BehindValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (54)

- You Can Thrive After Narcissistic Abuse: The #1 System for Recovering from Toxic RelationshipsDa EverandYou Can Thrive After Narcissistic Abuse: The #1 System for Recovering from Toxic RelationshipsValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (16)

- Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of PlantsDa EverandBraiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of PlantsValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (1424)

- Sex and the City and Us: How Four Single Women Changed the Way We Think, Live, and LoveDa EverandSex and the City and Us: How Four Single Women Changed the Way We Think, Live, and LoveValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (22)

- Unlikeable Female Characters: The Women Pop Culture Wants You to HateDa EverandUnlikeable Female Characters: The Women Pop Culture Wants You to HateValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (18)

- Summary: Fair Play: A Game-Changing Solution for When You Have Too Much to Do (and More Life to Live) by Eve Rodsky: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedDa EverandSummary: Fair Play: A Game-Changing Solution for When You Have Too Much to Do (and More Life to Live) by Eve Rodsky: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- The Myth of Equality: Uncovering the Roots of Injustice and PrivilegeDa EverandThe Myth of Equality: Uncovering the Roots of Injustice and PrivilegeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (17)

- For the Love of Men: From Toxic to a More Mindful MasculinityDa EverandFor the Love of Men: From Toxic to a More Mindful MasculinityValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (56)

- Abolition Democracy: Beyond Empire, Prisons, and TortureDa EverandAbolition Democracy: Beyond Empire, Prisons, and TortureValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (4)

- Fed Up: Emotional Labor, Women, and the Way ForwardDa EverandFed Up: Emotional Labor, Women, and the Way ForwardNessuna valutazione finora

- Silent Tears: A Journey Of Hope In A Chinese OrphanageDa EverandSilent Tears: A Journey Of Hope In A Chinese OrphanageValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (29)

- Fallen Idols: A Century of Screen Sex ScandalsDa EverandFallen Idols: A Century of Screen Sex ScandalsValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (7)

- The Longest Race: Inside the Secret World of Abuse, Doping, and Deception on Nike's Elite Running TeamDa EverandThe Longest Race: Inside the Secret World of Abuse, Doping, and Deception on Nike's Elite Running TeamValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (59)

- Amateur: A True Story About What Makes a ManDa EverandAmateur: A True Story About What Makes a ManValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (96)

- Tears of the Silenced: An Amish True Crime Memoir of Childhood Sexual Abuse, Brutal Betrayal, and Ultimate SurvivalDa EverandTears of the Silenced: An Amish True Crime Memoir of Childhood Sexual Abuse, Brutal Betrayal, and Ultimate SurvivalValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (136)

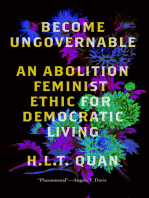

- Become Ungovernable: An Abolition Feminist Ethic for Democratic LivingDa EverandBecome Ungovernable: An Abolition Feminist Ethic for Democratic LivingNessuna valutazione finora