Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Constitutional Law II - Colby - Spring 2007

Caricato da

superxl20090 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

21 visualizzazioni64 pagineOutline

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

DOC, PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoOutline

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato DOC, PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

21 visualizzazioni64 pagineConstitutional Law II - Colby - Spring 2007

Caricato da

superxl2009Outline

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato DOC, PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 64

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW II OUTLINE

SCOPE AND INTERPRETATION OF CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS

These rights are framed in extremely open-ended and vague terms such as:

due process of law,

privileges and immunities,

cruel and usual punishment,

equal protection of the laws, etc.

Requires a lot of interpretation y the courts and affords a great amount of power to the federal courts comined with the

institution of !udicial review from Marbury v. Madison. "anguage of the #onstitution does not give specific, case-related

answers, rather it raises questions that must e answered y the government, primarily through the courts.

Rights can e read roadly or narrowly.

o Read too roadly, they interfere with the operation of $overnment, its aility to protect the people from

threat or operate in an efficient manner.

o Read too narrowly, infringe on the rights of the people, so cherished the %ramers found fit to include in

the #onstitution.

o &ow to alance these concerns' (orality, safety ) security, privacy, personal lierty.

*nterpretation can turn on one+s theory of statutory,constitutional interpretation -NOTE: *n class we returned to

these modes of analyses TIME AND TIME AGAIN!!.:

o Originalist / "oo0 to the meaning at the time the #onstitution was written or the 1mendment ratified.

"i0e a written contract with a fixed meaning. 2ermit unelected and politically unaccountale !udges to

change the law. 3trong supporters: 3calia ) Thomas.

o Textualist / 1ttempts to interpret solely on the asis of the text. 4sually tied to originalist school of

interpretation, ut not always. The literal text is controlling, it is the final product of the legislature. 5ut it

can ta0e on different meanings as new situations or technologies arise.

o Non-originalist / #onstitution was drafted w, language road enough to e flexile and applicale over

time. *nterpretation permits the living #onstitution to adapt to prolems and crises that did not exist at

the time of the %ramers. 6on+t elieve they are interpreting it differently than originally intended, rather

interpreting the same text and rights in the context of an evolving society.

o Common Law & Precedent / "oo0 to the common law evolution of the law on the matter. *dentify cases

decided on similar matters and analogi7e or distinguish them from the current case. #losely associated

with the non-originalist mode of interpretation.

o Political-process / 5ased on #aroline 2roducts %8 9. :iew that !udiciary+s role is as guardian of the

political process. Requires greater scrutiny for actions that undermine the political process or urden

discrete and insular minorities who are unale to defend themselves via the political process.

PRE-CIVIL WAR INTERPRETATION OF CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS

;arly view: 5ill of Rights does not apply to the states.

5arron v. 5altimore -<=>>. / ?wner of a wharf accused the #ity of 5altimore of changing the river flow and

therey and rendering the wharf property virtually worthless. #laimed a ta0ing under the %ifth 1mendment of the

4.3. #onstitution.

o (arshall did not reach the Ta0ings claim, ecause he held that the 5ill of Rights does not apply to state or

municipal action. 1pplicale only to federal government actions.

o #onstitutional arguments for (arshall+s view:

istorical / 5oR was created in a historical context concerns of anti-federalists and fear over

the new federal government, not local government.

!tructural / 2oints to the fact that the #onstitution is a compact etween the people of the 4.3.

and the new federal government they created. *t has nothing to do with citi7ens+ relationships with

the state or local governments.

<

Textual - There is a specific section prohiiting state action in the #onstitution, and this is made

explicitly applicale against the states. Thus the 5oR, which are generally worded, apply only to

the %ederal government.

?dd decision for (arshall, ecause he was usually one to decide cases in a way to enhance the federal

government+s power@ 5ut here at the end of his career, he gutted the aility of the 5oR to apply to the states.

o %ollowing this case, the state governments were free to !ail people for undesireale speech, search w,o

warrants, discriminate ased on religion etc.

(arshall writes that it is a very easy case. 5ut that did not have to e true. ;ven some state courts had held that

the 5oR limits state power.

o Two ways a !udge could come out the other way:

Textual / %irst 1mendment applicale specifically to #ongress -and so not the state

governments.. The rest are written in the passive voice, and could e read as road prohiitions

applicale to any 4.3. governments. 5ut runs up against (arshall+s textual arguments...

Natural Law "#nalienable $ig%ts& ' "oo0 ac0 to the 6eclaration of *ndependence, Ae hold

these truths to e self-evident ... life, lierty, and the pursuit of happiness. 8atural law rights.

5oR is a partial explication of these natural law rights and therefore are applicale to all levels of

government.

o 5ut natural law theory had een re!ected for a more positive approach that had ta0en hold y <=>>. 8o

longer in vogue.

8atural law theory has not disappeared. *t lives on in international human rights law, which

postulates that all people naturally have these inalienale rights, regardless of eing orn into a

society that does not recogni7e them.

3ome commentators still draw upon natural rights themes in supporting the asis of some

lierties and rights.

1uses following -or continuing after. 5arron v. 5altimore

3lavery

#rime to form or !oin a pro-aolitionist party, felony to pulish or distriute aolitionist material.

#riminali7e free lac0s in the 3outh -prevent role models.

14TH AMENDMENT POST-CIVIL WAR

&istorical ac0ground

%orce the 3outh to !oin the 4nion and force them to do away with slavery:

o 3et up puppet governments in the 3outh. 2resident appointed y proclamation the governors of the

southern states. 8orth dictated how they would vote.

o #onventions were convened to ratify the <>th 1mendment, ut only those southerners who supported the

aolition were permitted to attend.

<>th 1mend B constitutionali7ation of the ;mancipation 2roclamation.

Radical Repulicans too0 over #ongress. ;nvisioned a reconstruction that went far eyond what "incoln had in

mind. They sought full citi7enship for 1fro-1mericans.

RR pass a civil rights ill over the veto of 2resident Cohnson, who elieved it went eyond #ongress+ power. %ed

government did not have the authority for civil rights laws. This upsets the RR and they nearly impeach and

remove him from office.

;ven the anti-slavery forces, cherry-pic0 pro-4nion representatives in the 3outh felt the <9th 1mendment and the

#ivil Rights 1ct went far too far. 3o the prospect for ratification y D of the states was loo0ing dim.

RR struc0 ac0 w, a vengeance. Reconstruction 1ct ignores the new governments in the 3outh and put them

under military control and occupation. #onditioned readmission on adopting <9th 1mendment, permitting full

voting rights to lac0 1mericans, etc. 1ll gave in y <=EF.

The first interpretation of the <9th 1mendment strictly construed the language to apply only to issues related to

involuntary servitude and end-runs around the aolition of slavery.

o 2rimary purpose was to enforce the ;mancipation 2roclamation.

o $et around the 5lac0 #odes

G

#onstruction of the <9

th

1mendment+s 2rivileges and *mmunities #lause

The 3laughter-&ouse #ases -<=E>. / "1 utchers challenged a law that granted a monopoly to one corporation to

engage in the usiness of operating a slaughterhouse. ?nly certain utchers are permitted to operate. 3ome

utchers were not permitted to practice their craft in their hometown. #laimed this law infringed on their

fundamental constitutional right to practice their trade.

o *nterpreted oth <>

th

) <9

th

1mendments as designed solely to achieve the goal of emancipating and

protecting former slaves.

o <>th 1mendment argument: *nvoluntary servitude ,c law forces them to sell laor in another manner.

#ourt re!ects on historical grounds <>th amend only aout race-ased slavery. 1dded involuntary

servitude to cover slavery y another name. Tortured reading in any case ,c law does not force the

utchers to wor0 in any particular manner. Throw-away argument y 2s.

o <9th / 2 ) * argument: &eart of 2+s argument. 5ut court distinguished tw state 2 ) * and federal 2 ) *.

&ard to follow ,c argument is nonsense. #oly: %estering garage.

6istinguishes the previous interpretation of 2)* from 1rt. *:, H G as the 2)* of the citi7ens in

the several states, rather than the 2)* of citi7ens of the 4nited 3tates. The state-level 2)* are

the road natural law rights. 5ut the federal 2)* rights are narrow and severely limited.

6oes not specifically enumerate all federal 2 ) *, ut gives some limited examples.

o <9th / ;2 argument: ;xpressed dout that any action of a state not directed at discrimination against the

negroes as a class will ever come w,in the purview of ;2. -?viously mista0en@.

o Ith / Ta0ings: 6ismissed as w,o precedent.

6*33;8T: #laims <9th amend 2 ) * is road and meant to e road. To apply natural rights protected y federal

constitution to the state governments and ensure those states no longer infringe these fundamental, inalienale,

$od-given rights. *n part, this includes the 5oR, ut even more roadly than that@ $ives practical effect to

6eclaration of *ndependence.

o 2ressing argument that did not win the day in 5arron.

o 2oints to 1rt. *:, H G, which also uses the 2 ) * language. Those words mean the same thing in <9th

1mend. Thus the amendment is designed to protect the same rights in citi7ens against infringement y

their own state government, as 1rt. *:, H G does for out-of-state 4.3. citi7ens in a foreign state.

o *nterpretation y ma!ority ma0es <9th 1mend 2 ) * redundant@ 3tates can never interfere with federal

prerogatives or federal rights anyway. The 3upremacy #lause ta0es care of that. 3tate+s could never ta0e

away, for example, the right to

6ifference in interpretation: A&?3; rights are at sta0e' -6issent.. ?r A&1T rights are at sta0e' -(a!ority..

6issent seems to e a more natural reading. The ma!ority is twisted.

Ahy the warped reading'

o 2reserve the institution of federalism. #oncern that the <9th 1mendment will ring aout a sea change in

#onstitutional law.

o ;rr on the side of conservatism. %ederal power would e radically enhanced. -1s it is today.. 4nless the

language was crystal clear that the %ramers wished such a massive change in the structure of the 4.3.

government, court would avoid reading the language in that way.

o 6on+t want to ta0e responsiility for all the civil rights of the people, which up until that time, was the

province of the state governments.

o 6id not elieve the framers of the amendment had such a sea change in mind. The history was recent and

unoscured y time, and -allegedly. reflected a narrower intention of extending asic rights to afro-

1mericans.

3ort of originalist argument, only done almost contemporaneously, rather than y dusting off the

arguments of centuries ago as is common today.

*ntention of the sponsors

o 5oth &ouse and 3enate sponsors specifically referenced protection against state government intrusion on

natural law fundamental rights and the first = amendments@@ Restrain the powers of the 3tates and force

them to recogni7e at all times these fundamental guarantees.

o Thus significant evidence that, even accepting an originalist methodology, the ma!ority still got it wrong,

as it would seem the framers did desire to effect a sea change in the alance of powers in our federal

>

system. 2aid for these changes in lood. 5ut then 3laugher-&ouse case read the federal 2)* right out of

the <9th 1mend.

o 54T the intention of the sponsors is not necessarily the intention of all of Congress.

MODERN 14TH AMENDMENT PRIVILEGES & IMMUNITIES

The decision in the 3laughter-&ouse #ases has essentially gutted the 2rivileges and *mmunities of the <9th 1mendment,

limiting them to a few narrow incidents of 4.3. federal citi7enship.

3ome have argued for a revitali7ed <9th 1mend 2 ) * clause as the locus of sustantive federal civil rights.

-Rather than dividing due process into sustantive and procedural'.

Right to travel etween states and out of the country has not een grounded well in any particular constitutional

doctrine and may fit in the <9th 1mend 2 ) * clause. ;dwards v, #alifornia -<J9<. -anti-um entry to #1 law..

5ut in the same case it was argued that it should e grounded in the #ommerce #lause instead.

o 5ut durational requirements for welfare have erratically een grounded in the ;qual 2rotection #lause@

3hapiro v. Thomson -<JKJ. -stri0ing one-year residence requirement efore welfare enefits distriuted.L

6unn v. 5lumstein -<JEG. -stri0ing one for voting.L 3tarns v. (al0erson -<JE<. -upholding for in-state

tuition.L (emorial &ospital v. (aricopa #ounty -<JE9. -stri0ing for free medical care.L 3osna v. *owa

-<JEI. -upholding for ringing divorce proceedings against a nonresident..

Revival of the <9th 1mend 2 ) * #lause'

3aen7 v. Roe -<JJJ. / 3#?T43 struc0 down a #1 law that estalished a lower welfare enefit for recent arrivals

than to those who had resided in the state for more than < year.

o :iolates federal 2)* clause to pay less welfare enefits to new residents than to residents meeting a

durational requirement.

o 6istinguished welfare enefits from the type of portale enefits that may encourage outsiders to enter

the state on !ust long enough to gain them and then return to their own state: in-state tuition and divorce.

5ut what aout free medical care' That too could e portale@

#aused a lot of excitement in the legal community. 5ut since then the hysteria has died down completely.

Reali7ed it was a very narrow decision.

o The right to travel tw the states is one of those rights that did not exist efore the federal government,

did not exist prior to the 4nion.

o Thus it falls within the 3laughter-&ouse rule. Too0 a rare opportunity to enforce the limited federal 2)*

that were distinguished from the general, plenary power over 2)* vested in the states.

C. Thomas+ dissent far more interesting: 3uggests a willingness to accept the theory of the dissent in 3laughter-

&ouse. ?pen to reevaluating...

> components of the right to travel

Right to leave and enter another state. -;dwards.

Right to e treated as a welcome visitor, not an unfriendly alien. -4.3. #onst. art *:, H G.

%or travelers who elect to ecome permanent residents, the right to e treated li0e other citi7ens of that state.

-3aen7.

DUE PROCESS AND THE INCORPORATION CONTROVERSY

?ver time, the asic lierty guarantees of the 5oR were made applicale to the states, ut through an unli0ely legal asis:

the due process clause of the <9th 1mendment.

Theories for incorporation under <9th 1mend. 62:

o &as its own force and does not require any incorporation of the 5oR or other constitutional amendments.

-CC. %ran0furter ) &arlan.

o *ncorporates fundamental rights, some of which are listed in the 5oR. ?nly those that are fundamental

will e incorporated and enforceale against the states. -C. #ardo7o.

o Totally incorporates the 5oR -C. 5lac0.

3poradic incorporation

o Ta0ings clause / #hicago, 5urlington ) Muincy RR -<=JE..

9

o Recognition of possiility of incorporation of 5oR via 62 #lause / Twining -<JF=..

o <

st

1mend. free speech clause / $itlow v. 8ew Nor0 -<JGI..

2artial incorporation view O2al0o-1damson 6octrineP

2al0o v. #onnecticut -<J>E. / #hallenge to state criminal law permitting the state prosecution to ta0e appeal and

su!ect a criminal defendant to doule !eopardy.

o ?nly fundamental rights, essential to ordered lierty are incorporated into the 62 clause of <9th

amend. %ound that the K

th

1mendment was fundamental in capital cases and essentially incorporated it

against the states.

o 1dvocates a fact-ased approach. 3tart from the facts of the case, determine whether the actions violate a

fundamental right, then that finding will guide decision to incorporate the corresponding 5oR provision

into the <9th 1mend. 62.

o #ardo7o finds that action that is intended to correct an error in the !udicial process, not to harass a

criminal defendant, and so the rule against doule !eopardy is not a fundamental one. #an imagine fair

and free societies -;urope. that have no such protection.

1damson v. #alifornia -<J9E. / #riminal defendant challenged conviction where prosecutor commented on his

refusal to ta0e the stand.

o C. Reed that <9th 1mend 62 guarantees only a fair trial and that does not extend to the right against

self-incrimination that is en!oyed at the federal level.

;volutionary view of 62. *ndependent potency of 62 #lause. 1 twist on the selective incorporation view.

o C. %ran0furter+s concurrence in ''''

3hould encompass new rights that are appreciated in our society. #ardo7o wanted only to apply to

traditional natural law rights. Today there may e others that should e recogni7ed.

3upported y open-end language of the #onstitution. "iving #onstitution view.

o 2rolem is that if too flexile, grants no predictaility to the law Q !udicial activism

Total incorporation view

C. 5lac0+s dissent in 1damson

o 5elieve in a total incorporation of the 5oR y the 62 clause of <9th 1mend. 1ll of the 5oR are

enforceale against the states.

o Ot%er rights not codified in the #onstitution are not protected y 62. Textualist and originalist approach.

Re!ects the natural law approach.

;ffect of total incorporation

o ;xpands protections of lierties

4nconcerned aout tying the hands of the states y enforcing these rights. Aritten words of the

#onstitution trump.

o Restricts !udicial activism

8atural rights view permits !udges to legislate their own constitutional rights and gives them a

free hand to legislate ased on own mores,opinions.

* further contend that the natural law formula which the #ourt uses to reach its conclusion in this

case should e aandoned as an incongruous excrescence in our #onstitution.

(ore predictale for state legislators and executive authorities.

%ederalism argument

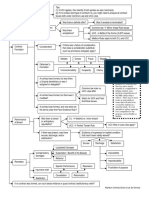

$raphs

<. G. >. 9. I. K.

I

Rey to graphs aove. (odels for incorporation of 5oR and scope of <9th 1mendment 62

o 5ill of Rights

o #overage of <9th 1mendment 6ue 2rocess #lause

:iews of various !ustices and schools of thought concerning <9th 1mendment

o $<: #ardo7o view, partial incorporation ased on natural rights theory. 3ome 5oR are fundamental ) are

protected y 62 #lause, ut some aren+t. *n addition, there are some fundamental rights that are not

enumerated in 5oR ut still protected y 62.

o $<: 5lac0 view - Total incorporation. #o-extensive and no more.

5ut if 62 was shorthand for all of the 5oR, than why is there a 62 clause in the Ith 1mendment'

*t would seem that the Ith is all you need@

o $>: %%,&arlan / *ndependent potency, evolving theory of rights. 3ome overlap, ut large ody of rights

outside the 5oR and these rights are not only the historically recogni7ed ones. 1lso, some contradictions

of a right in 5oR may on the facts n

6idn+t view it as incorporation, ut as overlap on the asis that oth happen to protect a specific

fundamental right.

o $9: (urphy: ;verything in 5oR is fundamental, otherwise they would not have een incorporated into

the 5oR. 5ut the 62 covers other unenumerated rights. Total incorporation and then some.

o G5: Brennan: 62 #lause incorporates virtually all of the 5oR w, minor exceptions and has a sustantive

component that protects a vast array of other lierty interests. Rights, if incorporated, must e

incorporated in full. *f clause is incorporated against the states, it is done so wholesale.

This view has A?8 ?4T. ?nly a couple of rights in the 5oR has een incorporated against the

states, and done so in full.

1ll doctrine accompanying the incorporated right are 1"3? rought in against states

2revents the dilution prolem that worried 5lac0.

?ther rights outside the 5oR have also een found to e fundamental and protected y the <9th

1mend 62 #lause itself.

o $K: 4ltra-conservative view: 62 clause does not incorporate 5oR except for those that deal with

2R?#;33.

Three primary issues of deate etween total and selective incorporationists:

&istory and drafters+ intent

%ederalism

1ppropriate role of the !udiciary

Rectifying past mista0es'

3trongest rationale for road incorporation of 5oR and other fundamental rights through the <9th 1mend 62

#lause: %ollowing the emasculation of the 2)* #lause in 3laughter-&ouse, the #ourt used another clause,

textually inappropriate, to effectuate the original understanding and purpose of the <9th 1mend. Thus the

incorporation through 62 is really !ust a compensation mechanism for the loss of the 2)* #lause

o C. Thomas suggested it may e time to stop reading 62 to mean what it doesn+t mean, and revive the 2)*

and employ it to cover much -all' more' much less'. of the rights now covered y 62.

?n the other hand, perhaps most of the legislators may not have understood that their vote for the <9th

1mendment would e construed as roadly as it is applied today.

o ;xample: Eth 1mend right to !ury in civil controversy with 1*# over SGF@

*ncorporation today is ta0en for granted.

o *t is hard to imagine a nation in which the 3tates are free to infringe on a person+s freedom of speech,

religion, or criminal procedural protections. Revo0ing the incorporation of the 5oR would e

unacceptale to virtually any 3upreme #ourt !ustice.

o The attle today is over the scope of the unenumerated rights. The incorporation of the 5oR is safe from

attac0.

#ontent of *ncorporated Rights

*s the provision of the 5oR as incorporated against the states identical to the federal version' 3#?T43 has not

een clear on this issue.

K

o %irst 1mendment applicale to the same extent. 8o watered down, su!ective version.

o 54T a couple of exceptions: 3#?T43 has upheld the constitutionality of K-person !uries -rather than <G.

and nonunanimous !ury verdicts in criminal cases.

LEVELS OF SCRUTINY

6efinition and purpose

*nstructions for alancing. *nforms courts as to how to arrange the weights on the constitutional scale in

evaluating particular laws.

The choice of level of scrutiny is often outcome-determinative.

o 1rea involving great suspicion of the government or a fundamental right at sta0e B high urden.

o 1rea of general deference to the legislature B minimal urden on the government.

Caroline Products Foo!o" 4

1rticulated the idea that different constitutional claims would e su!ected to varying levels of review. 1lso gave

rise to the political process theory for distinguishing which claims should e su!ect to those higher levels of

scrutiny. ;xtremely influential.

There may e narrower scope for operation of the presumption of constitutionality when legislation appears on

its face to e within a specific prohiition of the #onstitution, such as those of the first ten amendments. . . . *t is

unnecessary to consider now whether legislation which restricts those political processes which can ordinarily e

expected to ring aout repeal of undesirale legislation, is to e su!ected to more exacting !udicial scrutiny

under the general prohiitions of the %ourteenth 1mendment. . . . 8or need we enquire . . . whether pre!udice

against discrete and insular minorities may e a special condition, which tends seriously to curtail the operation of

those political processes ordinarily to e relied upon to protect minorities, and which may call for a

correspondingly more searching !udicial inquiry.

Thus, three situations giving rise to heightened inquiry:

o :iolates or implicates one of the protections set forth in the 5ill of Rights.

o 4ndermines or restrictis the political process

o 1ffects a discrete and insular minority

"evels of 3crutiny 6efined

Rational asis test

o "aw will e upheld if it is rationally related to a legitimate government purpose.

o The purpose of the law need e the actual goal / any conceivale legitimate purpose will do.

o (eans chosen needs only e a reasonale way of achieving that purpose.

o 5urden on plaintiff to show that the law fails this very deferential test.

*ntermediate scrutiny

o "aw will e upheld if it is substantially related to an important government interest.

o 5oth the government+s o!ective -important. and the means -sustantially related. must meet a higher ar.

o $overnment has the urden of proving the action,law meets intermediate scrutiny.

3trict scrutiny

o "aw will e upheld if it is necessary to achieve a compelling government purpose.

o $overnment interest must e vital / compelling.

o (eans must e show to e the least restrictive or least discriminatory alternative.

o $overnment has the urden of proof under this intensive review.

Scrutiny spectrum:

8o scrutiny ----,---Rational asis ---,--- *ntermediate ---,--- 3trict ----,--- Total scrutiny

$ovt can do 8eed not achieve "ater' 3tate must have 8othing can !ustify

anything ) governmental interest compelling govt state infringement

no rights will ut have some rational interest and e

e protected !ustification and serve some strictly tailored to serve

E

legitimate purpose -##. that govt interest -6##.

SU#STANTIVE DUE PROCESS

&istorical precedents

8atural law tradition viewed a written constitution, not as the initial source, ut as a reaffirmation of a social

compact preserving preexisting fundamental rights. There rights were entitled to protection whether they were

explicitly listed in the #onstitution or not.

o #alder v. 5ull -<EJ=. / %or: C. #hase opinion, pg 9=E. 1gainst: C. *redell, pg. 9==

6uring the (arshall #ourt era, the natural law view declined and asing !udicial !udgment on general principle,

on the reason and nature of things went out of vogue. -&ence 5arron..

3laugher-&ouse+s reading out of the 2)* clause from the <9th 1mendment loc0ed the most ovious avenue to

challenge the sustance of state laws infringing on fundamental, ut unenumerated, rights. This delayed

protection against state infringement in federal courts for many years.

#ontinuation on deate concerning the interpretation of 62 #lause to cover sustantive rights, rather than !ust the

process afforded efore rights are ta0en away y the state.

o #onservative view: #overs only the process required.

3ustantive process is an oxymoron. 5etter internal logic.

&owever, seems unacceptale to permit the states to roam free w,o sustantive

o "ieral view: #overs also sustantive rights

8o legal process in the world can authori7e the state to ta0e away a fundamental lierty right,

such as the freedom of speech. #annot say that states can aridge the fundamental

62 #lause incorporates these fundamental rights against the state, ecause it would necessarily e

a violation of process to enact legislation that violates a fundamental natural human right. -'.

?nly reason we have 362 is ,c of the 3laughter &ouse cases. They read the 2)* cases out of the

<9th 1mendment altogether. %orced to cram these rights into 62 #lause where textually they do

not fit in. 5ac0door method to achieve the original purpose of the <9th 1mendment.

6espite the clearer logic of the conservative view, the current !urisprudence recogni7es 362. The real question

involves the scope of 362 protections.

&istorically though, it is not that easy. 3ome courts had interpreted 62 to have a sustantive element long efore

the <9th 1mendment@@

o %amous examples of courts deciding on the asis of 362 even efore the "ochner ;ra:

Aein... / 8N #ourt interprets 8N #onstitution 62 #lause, reads it far roader than to cover only

legal process. This would e throwing entire restraint away. 1 ill that ta0es away a fundamental

freedom should not e considered a law at all.

:ery high profile case, all 0new aout it.

6red 3cott / 3#?T43 invalidates a fed law that made any slave transported into a free states

ecomes free. 3tri0es down the law as a violation of Ith 1mendment 62. 3laves are the property

of slaveowners. %ed govt cannot ta0e that away, no matter how much process of law is afforded

them. %undamental right to ownership.

6on+t forget this case. 3tri0ing example of the evils of 362. 6angers of the doctrine.

o The sharp distinction tw procedure and sustance was not so clear in that time. Aas not consider

illogical. ?nly with the advent of the %R#2 and the ;rie 6octrine did this mindset arise. Thus, it is not

unreasonale to thin0 that the framers of <9th understood 362 and intended it to have that effect.

o 3till it is only after 3laughter &ouse did the 62 #lause+s sustantive aspects really grow.

LOCHNER ERA: $UDICIAL INTERVENTION AND ECONOMIC REGULATION

&ints of economic lierty efore "ochner

;conomic lierties generally refer to constitutional rights concerning the aility to enter into and enforce

contractsL to pursue a trade or professionL and to acquire, possess, and convey property.

=

"eading up to the "ochner decision, the 3upreme #ourt made increasing references to the limits of state action

under the 62 clause. Though the #ourt upheld all those laws, the threat of the use of a sustantive economic

rights protection ased in 62 ecame clearer.

o %irst articulation of 362 right of lierty of contract. 1llgeyer -<=JE..

;stalishing a 362 right to contract.

"ochner v. 8ew Nor0 -<JFI. / 8N law prohiited the employment of a0ers for more than <F hours a day or KF

days a wee0. 8N !ustified the law on the asis of pulic health: health a0ers ma0e etter read. 5a0er challenge

the law as infringement of economic freedom.

o &;"6: C. 2ec0ham opinion struc0 down the law ased on 362 ecause the statute interferes with the

right to contract tw ;; and ;R. ;ffectively expanded the protection for lierty of contract outside the

scope of the #ontracts #lause, which protects against impairment of existing contracts, to prohiit

extensive government regulation even of contracts not yet made@

o 5ut still recogni7ed that the state has legitimate police powers to enact legislation to ensure the health,

mores, security etc. of the population. (a!ority simply claimed that this power was outweighed y the

;;-;R lierty to contract for laor.

"aor: 6iselieved that a0ers had no argaining power and needed laor law protection.

*nter!ected their own su!ective view of a0ers+ argaining power. ?r elieve that even if true,

were ideologically against interference in the mar0et.

2ulic &ealth: 6id not elieve that the profession of a0er was so harmful as to require

protection. The common understanding is that a0ing is not dangerous. ?nce again, w,o

citation. *nter!ected own opinion on the matter.

3afety ) 3anitary 2ractices: 8o reasonale asis to elieve that reduced hours would somehow

improve the food quality, ecause the state has the authority to do sanitary chec0s and control the

use of equipment etc.

o %ound the real goal was to regulate the 5a0er-;R relation, not protecting the pulic from unsafe food. To

alter economic and mar0et forces, not ensure safe read or healthy a0ers. #oncerned that anyody+s

hours could e regulated: lawyers, physicians, and any other profession.

o 1pplied a heightened -strict'. scrutiny to the infringement of this right. The language at the start of the

opinion has a ring of rational asis review -fair, reasonale, etc... 5ut in reality the court was second

guessing the legislature in the face of a determination aout which reasonale persons could differ.

Requires proof that the infringement on the right to contract e compelling -such as in the coal mine

context in which they upheld a similar law..

o *nspired y a philosophy of strong commitment to laisse7-faire economy and protecting usiness from

government regulation.

C. &arlan 6*33;8T: 1greed that there is a right to contract protected y the <9th 1mend. &owever, the court

should do what it claimed it was doing, review only for irrationality. #ourt should defer to legislature+s !udgment

so long as reasonale men can differ as to whether a law achieves valid police power goals. -Rational asis

review.. Ahy'

o "egislature etter situated to gather evidence and ma0e and informed decision on the topic.

o 3trict !udicial review suverts democracy.

C. &olmes 6*33;8T: -Classic most famous opinion.. Cudges should not inter!ect their own political or

economic theories into their interpretation of the #onstitution. This right of freedom to contract for one+s laor is

not a fundamental right w,in the #onstitution, ut a conclusion ased on the !udges+ private elief in the laisse7

faire theory. There can e other fundamental rights esides those enumerated in the #onstitution, ut only when

they are grounded in tradition and consensus.

> themes from "ochner

o %reedom of contract is a right protected y 62 clause of I

th

) <9

th

amendments

o $ovt can interfere w, this right only to sever a valid police purpose: protecting pulic health, safety,

morals.

o #ourt will carefully scrutini7e legislation to ensure it truly served such a purpose.

1ftermath of "ochner

J

"ochner in effect prohiited the states from passing health regulation for wor0ers except in those rare cases in

which the profession is widely considered dangerous. (any laor and safety laws were struc0 down

o (inimum wage, anti-union contracts -yellow dog., maximum hours, restraints on usiness entry

o 5ut the prolem is that a law stood or fell ased upon the !udges+ opinion aout the matter. 3o in some

cases the 3upreme #ourt upheld laws within the aove categories

o 5itterly contested: (any of the decisions of the "ochner ;ra were I-9.

#ourt was constitutionali7ing the old order, even while the vast ma!ority of the people sought a new solution in

progressivism.

3truc0 down state laws such as the a0er+s maximum hour law on 362, and scores of federal laws as eyond the

authority granted y the #ommerce #lause, claiming that these matters were for the states@ Thus oth federal and

state progressive laws were under attac0 from the #ourt@ Thus ## and 362 comined to prohiit

o %ederal laws stuc0 down as unauthori7ed under #ommerce #lause

3checter 2oultry -<J>I.

#oal (ines -<J>K.

o 8ew 6eal legislation that was struc0 down y the court under 362 freedom to contract:

(inimum wage regulations for women -1d0ins., laws protecting unioni7ing, consumer

protection legislation, laws regulating usiness entry.

5ut there were exceptions:

o (uller v. ?regon -<JF=. / 4pheld the constitutionality of safety statute regulating the laor conditions for

women. #ourt found that they were sufficiently frail and helpless and required state protection.

?rigin of the 5randeis rief / practice of sumitting detailed factual riefs in support of a

particular -or against. a regulation.

The original 5randeis rief was <<> pages long and detailed the harmful effects of long hours at

nondomestic wor0 on the reproductive health of women.

5ecame apparent to the Ahite &ouse that 3#?T43 would stri0e down all 8ew 6eal legislation, whether

implemented at the federal or state level.

o %ireside #hat -<J>E. / %amous radio address to the nation. #ritici7ed the 3upreme #ourt as acting as a

superlegislature, reading in words that are not in the #onstitution, and eing a third legislature. Aant a

government of laws, not of men. 2roposed the court pac0ing plan.

o 1merican people were initially s0eptical of this plan, ut no so against it as one might thin0. There was a

significant chance that the people would come around to sanctioning the other two ranches to gut the

power of the 3upreme #ourt.

1 few wee0s after the radio address, 3#?T43 decided Aest #oast &otel -<J>E. / which expressly reversed the

1d0ins decision and permitted minimum wage regulations for women.

Today "ochner is one of the handful of despised, hated, and disparaged decisions in 3upreme #ourt precedent.

Ahy is "ochner so despised' Ahat was so wrong'

o 6ishonesty / claimed it was engaging in rational asis review when in fact it was applying a much higher

standard.

o 2oster child for excessive !udicial interventionalism

o (a!ority inappropriately in!ected their own economic and political theories into their interpretation of the

#onstitution.

o :ery inconsistent in the application of these rights.

Aays to critici7e "ochner

o 8o such thing as 362

o There is 362, ut covers only those rights enumerated in the #onstitution

o There is 362, and rights eyond the 5oR, ut not this one. 8eed more consensus.

o There is 362, and this is a right protected, ut still afford only rational asis.

DECLINE OF SU#STANTIVE DUE PROCESS FOR ECONOMIC RIGHTS

Reduced !udicial scrutiny of economic regulations

<F

8eia v. 8ew Nor0 -<J>9. / #hallenged a regulation setting the minimum price for mil0. 8eia owned a small

grocery store and was prosecuted. 6eferred to the state legislature.

o ;conomic scholars point out that the statute really made little sense. *f you have an over-supply prolem,

the last thing you want to do is artificially raise the prices.

o 5ut 8eia stands for the proposition that it is the legislature+s !o to figure out the est way to deal with

the prolem. #ourts should not stri0e it down !ust ecause it was unwise. 3till economic 362 was not

dead yet. The #ourt came ac0 and struc0 down other 8ew 6eal legislation for G more years.

3witch in time that saved the nine

Aest #oast &otel -<J>E. / 1nother challenge to minimum wage laws for women. This time Custice ?wen Roerts

switched sides, ma0ing a I-9 ma!ority for aandoning the "ochner doctrine. 6ramatic shift. (a!ority opinion

went so far as to say, Ahat is this freedom of contract' The #onstitution does not spea0 Oof thisP.

True rational asis review

#arolene 2roducts -<J>=. / #ourt upheld a federal law that prohiited the interstate sale of filled mil0 on the

asis that it was less nutritious and adulterated. 3ome question as to the actual detrimental effects of this

processed mil0.

o 4pheld the law under a very deferential review. 6ismissed the evidence that the law might e unwise or

ased on insufficient evidence.

o ;conomic regulations should e upheld if there is any conceivale rational asis, even if cannot e proved

that it was the legislature+s actual intent.

%amous %8 9. -Custice 3tone.

o (ost famous footnote in constitutional law history. $ave rise to 2olitical 2rocess %ailure Theory:

6istinguishing the situations in which the deferential review of #arolene 2roducts would not e

appropriate. These include laws that interfere with:

$eneral prohiitions of 5oR and <9th 1mend.

2er se rea0down / #onstitution is the supreme law of the land so a law enact that

contradicts a specific rights in the 5oR, which is not permitted, is already a rea0down.

1ctual textual support infers that they are fundamental. #ourt must aggressively enforce

rights the framers elieve would not e adequately protected y the political process.

1ttac0s on the political process itself

Right to vote

6issemination of information

1ctivities of political organi7ations

2articular religious groups or discrete or insular

"aws directed at discrete and insular minorities.

o 1ll these rights are unprotected y the political process ecause the laws either affect minorities, free

speech, or attac0 the democratic process itself. 3ituations in which the political process may rea0 down.

o Role of the courts is to protect the political process. *f it can e shown that the case deals with the 0ind of

minority that cannot protect itself in the political process, then the court may more closely scrutini7e the

law in question.

;x. 5a0er v. #arr / %ailure to redraw districts despite grossly unproportional representation.

;x. (c#ulloc0 v. (aryland / #annot tax the federal an0. Aould rea0 down the political

process as it would result in taxation w,o representation y taxing the money of a an0 that

enefits the country as a whole. &igh taxes on the an0 would e good for (6, ad for everyone

else. 1nd those outside of (6 would have no power to change the result. &ere the court must

step in to ma0e the correction.

(odern court+s view for reviewing the constitutionality of economic regulation. Review for any conceivale rational asis

Ailliamson v. "ee ?ptical -<JII. / ?pticans challenged a law that prohiited them from fitting of lenses to a

face, or duplicate or replace lenses into frames w,o a recent prescription from an ophthalmologist or optometrist.

#learly a very wasteful law. 4nfair to the optician who is clearly qualified simply to grind and replace lenses in

existing glasses. 2retty stupid law.

<<

o &;"6: 8ot the province of the courts to alance the pros and cons of a law, will not second guess or

sustitute their !udgment. 8eed only a rational asis, and possile rational ases include: catching

glaucoma, ensuring

o 5ut the court did 8?T cite any support for this supposed reason. 6oesn+t require any evidence. #ourt

doesn+t care aout the actual underlying reasons for the law, so long as the law itself is not totally

irrational. 5ased

*n "ochner ;ra wouldn+t even ta0e at face value the stated reasons for the laws they struc0 down.

o *n reality, rent-see0ing y politically influential and wealthy ophthamologists and their loying group@

3upreme #ourt has not struc0 down an economic regulation on 362 grounds since %6R+s chat.

o #eleration of 6emocracy

o Reu0e of the excesses of the "ochner ;ra.

REVIVAL OF SDP TO PROTECT NON-ECONOMIC RIGHTS

"ochner ;ra antecedents to non-economic 362

o (eyer v. 8eras0a -<JG>. / "ierty protected y <9th 1mend extends not only <9th 1mend protects all

rights necessary to the orderly pursuit of happiness

o 2ierce v. 3ociety of 3isters -<JGI. / 3truc0 down a law requiring all children to attend pulic school.

2arents have a fundamental right to educate their children as they see fit.

o 4nli0e "ochner, we continue to praise these cases, despite the fact that they were decided during the same

era and on the same grounds: 362.

*n (eyer, the law really targeted $ermans. *n 2ierce, it was targeting #atholics who sent their

0ids to private schools. 1t the time these were discrete and insular minorities, so 33 should apply.

5ut this is a cop-out ecause all languages and private schools were targeted / the 3#?T43 did

not stri0e them on those grounds, ut ,c they violated independent fundamental rights.

$riswold v. #onnecticut -<JKI. / #ourt struc0 down a #T law that criminally prohiited the use of

contraceptives, even y married couples in their own home. E-G. #ase involved the prosecution of ;stelle

$riswold of 2lanned 2arenthood opened a clinic and openly distriuted contraceptives.

o Ahat exactly was unconstitutional aout this #T law' :iolates the right to privacy. C. 6ouglas found

this unenumerated fundamental right and proceeded to apply strict scrutiny.

3tate claimed that the law is necessary to ensure against extramarital and premarital sex / idea is

that without access to contraception, people will e deterred from doing so. 5ut there were

already laws against adultery and fornications, so not least restrictive means.

o 5ut where is this right of privacy in the #onstitution'

6ouglass -(a!.. / 2enumras of the more narrowly focused <

st

, >

rd

, 9

th

1mendments. %S&'"()*)(

+,-.-!""/ )! 0" #oR 0-1" '"!,23.-/4 *o.2"5 36 "2"!-)o!/ *.o2 0o/" +,-.-!""/ 0-

0"7' +)1" 0"2 7)*" -!5 /,3/-!("8 #laims not to rely on the <9

th

1mendment or 362, ut the

road scope of the 5oR itself.

$olderg / J

th

1mendment evidence that there are other fundamental rights

&arlan / <9

th

62 #lause itself protects the right to privacy.

5lac0+s view is naTve ecause it is !ust as easy for a !udge to impose his personal view or

policy preferences within the -highly flexile. construction of an expressly enumerated

right.

o 6issents pointed out that this is the same theory as espoused in "ochner.

C. 5lac0 /. 1lthough there are some privacy protections in the 5oR, this is not one of them. ?nly

the rights of the 5oR are fundamental lierties. 5ut doesn+t this view violate the Jth 1mendment

which was designed !ust for this purpose'

Nes. &is view is inconsistent with oth the text and history of the J

th

1mendment -elow.

5ut still has a powerful force to it, ecause it is anti-democratic to find unenumerated

right. *t puts the power to stri0e down democratically enacted laws in unelected !udges.

*t+s one thing to use the anti-democratic tool of !udicial review y stri0ing down a

popular law

<G

5ut what is the history of the Jth 1mendment'

o (adison and the federalists did not feel that the 5oR was necessary ,c the structure of the government

was designed. 1nti-federalists were unsatisfied and demanded the 5oR.

o (adison and the federalists thought the 5oR was dangerous and a ad idea@

Aanted a federal government of limited powers. 5y listing specific rights, there will e a negative

implication that 54T %?R those prohiitions, the #ongress would e ale to do those things.

2eople will infer a roader scope of federal power than granted y the #onstitution as adopted.

1nother danger is that people would ta0e that list to e exclusive or exhaustive. The federalist

thought that would e disastrous. *t is impossile to list them all, and then those left out would

ecome fair game for regulation.

o *n the deates, (adison elieved he came up with an answer to these concerns: the comination of the J

th

and <F

th

1mendments.

<Fth 1mendment / all powers not given to the federal government are retained y the states.

-That didn+t wor0@.

Jth 1mendment / The enumeration in the #onstitution of certain rights shall not e construed to

deny or disparage other remained y the people.

o The history and text of the Jth 1mendment along w, the history and text of the <9th 1mendment are

powerful evidence to reut the notion that the whole enterprise of recogni7ing fundamental unenumerated

rights were intended y the framers.

o 6o we need the unenumerated rights of the Jth 1mendment to protect against the tyranny of the ma!ority'

&ighly unli0ely that it would e possile to amend the #onstitution to overrule a law that is an

affront to an unenumerated right if there is a political faction strong enough to get the law passed

in the first place.

#ounter-ma!oritarian prolem with discovery of unenumerated fundamental rights.

o Cudges were not elected in the first place. 6o not stand for office. 1nd yet have the last word on issue.

Thus, every time the !udges hold that some right is fundamental, they trump the will of the people.

o #an only e overturned with a constitutional amendment or upon the death and replacement of the

!ustices. Those and the crude chec0s of impeachment, stripping of !urisdiction, threats of expanding the

numer of !ustices -%ireside #hat..

o Thus the 3#?T43 !ustices are very circumspect and careful when they decide to recogni7e a new

fundamental right.

o 1ttempts to circumscrie scope of unenumerated fundamental rights while recogni7ing that some exist.

2enumras emanating from the 5oR

Aants to somehow tie the expansion of personal rights to the 5oR. 5ut penumras can

emanate wider or narrower as the !udge views appropriate -6ouglas..

C. 6ouglas was a 8ew 6eal !udge and hated Loc%ner. 3o he could not ring himself to

ground the right to contraceptives in 362.

3till, it is useful as a asis for loo0ing to the enumerated rights as guides and compare a

putative fundamental rights to them to see how the new one stac0s up to those.

362 Q Jth 1mend, ut so rooted in the history of the people as to e classified as fundamental in

the collective conscience -$olderg concurrence in $riswold..

5ut how does this permit the recognition of new rights' 6oesn+t account for the

possiility of change.

*f the right is so recogni7ed and randed into the collective conscious, how did the

offending law get passed'

62 is !ust the alance struc0 as a society etween lierty of the individual and the power of the

government -&arlan.. #an change over time. Tradition is one aspect, ut tradition is a living

thing... and not restricted to rules in the past.

5,c our tradition is a changing thing, new rights ecome fundamentalL others can wane

and fall out of fundamental status.

;xample of new right: Right to privacy in $riswold.

<>

;xample of a fundamental right falling out of favor: ;conomic rights in "ochner.

2rolem <: ;ven if we accept this theory, does that mean that unelected !udges are

supposed to e the guardians of these evolving, amorphous rights'

2rolem G: 6oesn+t the fact that the law was passed y duly elected legislators, enforced,

not repealed, and the legislators not thrown out of office suggest that there was no

consensus' Aon+t it always e the case' (ust always e a case or controversy efore

the matter can come efore the court.

o 5ut none of these approaches really provides a principled foundation for distinguishing the fundamental

right to contraception in $riswold from the fundamental right to freedom of contract in "ochner.

&ow does the #ourt identify a new fundamental right' ;xample: $riswold and its progeny.

o Ahat is it aout the #T law that ma0es it so offensive'

%ocuses on intruding into the edroom and regulating the use y married couples.

5ut #ourt suggested that #T could regulate or prohiit the sale of condoms.

3o is there really a fundamental right to contraception' ?r is the right something else' *t

doesn+t seem li0e this case answers that question.

"ater the #ourt struc0 down a contraception sale an, even to nonmarried people.

2rotection seems to extend only married couples. The #ourt seems to ta0e for granted that the

state could regulate the use y minors or unmarried.

3eems li0e unmarried couples and those having affairs have an even greater interest in

0eeping their privacy.

"ater the court expanded $riswold+s holding to all heterosexual, and eventually to

homosexual intimate relationships.

o 3o what is the method'

3omething of a common law method of derivation. Relies very heavily on precedent.

*n its essence a conservative institution, ut one that allows for slow evolution of the law.

?ther proposed theories for a method to finding fundamental rights:

2olitical process theory.

8atural law.

6eeply emedded moral consensus.

;isenstadt v. 5aird -<JEG. / ;xpands the holding in (riswold to stri0e down a law anning the distriution of

contraceptives to unmarried persons. 6enied ;2 to unmarried persons Q right to control repo B fundamental right

The Right to 1ortion

Roe v. Aade -<JE>. / 3tri0es down a TU law prohiiting all aortions except those necessary to save the life of

the mother. The question in the case oils down to: does this law infringe on a fundamental constitutional right' *f

so, what right' ;ven if it infringes a fundamental right, does it survive strict scrutiny'

o Nes. The right at issue here is the right to privacy. #ourt locates it in the sustantive part of the 62 right

in the <9th 1mendment and its guarantee of lierty.

o 5ut what 0ind of privacy is this'

8ot one of eing viewed or someone usting down the door li0e in $riswold. Really tal0ing more

aout autonomy, the right to ma0e certain private and touchy personal decisions.

3ustantially expands the scope of $riswold. 5ut that scope was already expanded y ;isenstadt.

3o $oe does not flow directly from $riswold, ut it is a much smaller leap from ;isenstadt.

1lso the concept of the right to odily integrity plays into this expanded scope of the right of

privacy. The right to control one+s own ody and ma0e decisions concerning it has long een

cherished.

5ased the right of privacy either on <9

th

1mend. 62 or the J

th

1mend. 8o penumras@

o 6oes the law survive strict scrutiny'

The answer to this question is more difficult. ;ven if there is fundamental right to privacy, the

state can infringe on that right if it has sufficient !ustification. TU give two reasons: -<. protecting

the health and welfare of the mother, -G. protecting the life of the fetus.

<9

#ourt alances the privacy interest of the mother with the state+s interest aove and found that:

#oncerning mother+s heath: 3tate cannot regulate in the <st trimester, ,c level of ris0 of

the aortion procedure is lower than the dangers at irth. 1fter <st trimester, state can

regulate how the procedure is done.

#oncerning the potential human life: 3tate can regulate, even proscrie, aortion

procedures after the point of vitality of the fetus, or aout the time of the Gd trimester.

o 5ut does that ma0e sense' *f the state has an interest in protecting potential

%uman li)e, why is the point of viaility important' Aouldn+t $riswold also

interfere with potential human life'

o *t seems that the state+s interest is actually in protecting not potential, ut actual

%uman li)e of a eing that could possile survive w,o the support of the mother.

5ut this means the #ourt decided when life egins@

5ut pro-life proponents elieve that a fetus, even emyo or 7ygote, is a )ull %uman li)e. 3o they

argued that they had a compelling interest in protecting that life. #ourt held that the state cannot

adopt one view of life to the exclusion of all others.

#ourt claims that it cannot decide when life egins / that such a question is a matter for

theologians, philosophers, and medical researchers to discover. 5ut it does seem to e deciding, at

least in the eyes of the law, that full human life does not egin at conception.

o Roe+s trimester framewor0:

%irst trimester: 8o regulation. 6ecision left to the pregnant woman and her physician. 8o

government interference greater than regulation for other medical procedures.

3econd trimester: #annot prohiit aortion, ut state can regulate in ways reasonaly related to

protecting the health of the mother.

Third trimester: 3tate can regulate, even proscrie, aortion except where necessary to save the

mother+s life.

o Rehnquist 6*33;8T: The whole complicated system seems li0e legislation@ This 0ind of horse-trading

and alancing is what legislators do, attempt to ma0e everyone happy. 8ot a slow, evolution, ut an

arupt rea0 and a creation of a comprehensive framewor0 for aortion. %inally, strict scrutiny is not

supposed to e aout alancing and splitting the difference. 3upposed to e lac0 ) white.

1nalysis of the Roe decision

Ahat gives them the right to ma0e such a determination'

o 8ecessity / the #ourt is called on to decide cases and controversies

o :alues are intrinsic to constitutional rights / #annot e completely value-free in constitutional

interpretation.

6elegating the decision

o 2erhaps rather than deciding when life egins, the #ourt is simply delegating the decision to the

individual, rather than to the state.

5ut #ourt cannot delegate the right to murder to the woman, so the #ourt must naturally decide

that full-fledged human life does not egin at conception.

o 6eeply difficult moral questions must e left to the individual, not imposed from aove y the

government.

#oncern among the pro-choice w, the viaility standard

o 3ome irth defects are detectale only in the later stages of the pregnancy. *f the fetus has reached the

point of viaility efore detection, the pregnancy cannot e terminated.

o :iaility depends on the state of medical science. 1s science advances, the right of privacy of the woman

shrin0s.

2oorly reasoned and written opinion. 3o what went wrong'

o 1ttempt at alancing two conflicting interests. The interests are asolute and nonnegotiale on oth sides.

The #ourt is concerned that this matter cannot e left to democracy, ecause once one side gets a slight

ma!ority, it will crush the other side and violate what they consider

<I

o $ood old fashioned !udicial alancing act. 5est possile compromise. 5ut is this acceptale' *s this the

function of the court'

o #ourt did not want to say that they were defining, even only as a legal matter, when life egins. 3o it

wrote aout potential life instead. 2erhaps they thought that in doing so they could coax those who

were pro-life into accepting the opinion as less of an affront to their eliefs.

2erhaps the #ourt had hoped to stri0e a argain that would placate oth sides. *f so, they were greatly mista0en.

The views on each side are too strong. 2ro-life / aortion B murder. 2ro-choice / state-coerced ay incuators.

Summary: The case ma0es far more sense as a legal and constitutional determination of the eginning of actual human

life. "eaves open whether science, religion, or philosophy determines a different time for the eginning of life. *t is within

its power to determine when life egins at law / and they did so, ut they were too chic0en to come out and say it.

o #onsistent with the traditional common law view of separate life eginning at the quic0ening. 1fter that

point the woman assumes legal responsiility

o #onsistent with the ma!ority of 1mericans+ view at the time, as well as today.

Three options esides Roe assuming there is a fundamental right to odily integrity. "oo0ing at how compelling

the state+s countervailing interest is:

o The state+s interest in protecting potential life is not compelling, protecting actual life is. 1nd a fetus is

not actual life until viaility. -;ffectively what the #ourt decided, ut did not admit..

o %etus is not an actual human life efore irth / Right to aortion throughout the pregnancy.

o Cudges not qualified to decide when life egins, so leave it up to the state. 3o if Texas+s democratically

elected legislature decides that life egins at conception, it can an all aortion.

1ll three will e quite unsatisfactory to a large percentage of the population.

5ut how can the court avoid deciding the question' The controversy was efore them.

RECASTING ROE UNDUE #URDEN TEST

1ortion Regulation from $oe to Casey

The reaction to $oe included attempts to amend the #onstitution to permit the states to enact laws

regulating,prohiiting aortion or to create a constitutional definition of life as eginning at conception. 8one

were successful.

3ince <JEK, opposition to Roe ecame a central plan0 of the Repulican platform. #ontinuing Repulican efforts

to appoint anti-Roe 3upreme #ourt !ustices. Regan promised to appoint !ustices who would overturn.

o &owever, in the <J years etween Roe and #asey, Repulicans has dominated the presidency. ?nly the 9-

year term of 2resident #arter intervening, and he had the distinction of eing the only president to serve a

full 9-year term w,o appointing a single 3upreme #ourt !ustice.

#ourt continued to stri0e down laws designed to limit the availaility of aortions y other means:

o 3pousal consent requirements / struc0 down in 6anforth -<JEK..

o 2arental consent requirements / 5lan0et consent resulting in >2 veto of aortion for mature minors /

struc0 down in 5ellotti * -<JEK.. 5ut can involve parents in the decision so long as it does not result in an

asolute, and possily aritrary, veto. 5ellotti **.

o 2rocedure that requires either parental consent or a !udicial determination regarding minor+s maturity to

ma0e a decision to aort. 1shcroft -<J=>..

o 2arental notification also acceptale. (atheson -<JJF.. 5ut struc0 down a law that requires oth parents

e notified 9= hours prior to the aortion is performed. &odgson v. (8 -<JJF..

o Regulation of medical practices: protection of viale fetuses.

Requirement that aortions performed in the first trimester must e performed in a hospital, rather

than an outpatient clinic, unconstitutional. 10ron -<J=>.. &ospitals much more expensive and

resulted in significant ostacle in the path of women see0ing an aortion. #ourt struc0 down a

variety of other procedural hurdles placed in front of aortion or that otherwise would chill the

practice.

o $overnment refusal to fund aortion.

<K

3ustaining (edicare enefits for childirth, ut not for nontherapeutic aortions. (aher v. Roe

-<JEE.. #ourt held that the funding decision did not interfere with a fundamental right, so applied

a rational asis test.

;xtended to apply to a restriction on aortion counseling for any pro!ect receiving federal

funding. Rust v. 3ullivan -<JJ<.. 5ut 2resident #linton rescinded them efore they went into

effect.

Cudicial questioning of $oe / in the years etween $oe and Casey, several Custices express dout aout certain

aspects of the decision.

o 4ndue urden approach / %irst articulated y C. ?+#onner in her dissent in 10ron, was proposed as an

alternative to the trimester approach. Rationale: 1s medical science progresses, the two ends of $oe,

medical danger to the mother and viaility of the fetus were on a collision course somewhere in the Gnd

trimester. 8ot a long-term viale framewor0.

o ?thers have called for the end of the trimester approach or to overrule $oe altogether. The strong criticism

of $oe in Aester v. Repoductive &ealth 3vs. -<J=J. caused some commentators to pronounce the end of

$oe and the right to aortion was near.

1fter years of Repulican appointees and retirements of nearly all lierals on the #ourt. ?nly two !ustices were

openly for upholding $oe. Thus, for $oe to survive, > of the I new Reagan appointees had to vote in favor of

upholding.

o This seemed li0e a long shot, if not impossile.

o ?n the last day of the term, the #ourt had still not handed down the opinion.

o 2ro-choice movement had already scheduled its protest march

o *n the voting conference, Rennedy voted with the conservatives to overrule Roe I-9. Rehnquist had

already egun

o 5lac0mun was writing a dissent when he received a note from C. Rennedy, who had een meeting secretly

with CC. 3outer ) ?+#onnor and decided to change his vote.

The 4ndue 5urden 3tandard and the modern right to aortion.

2lanned 2arenthood of 3e. 2a. v. #asey -<JJG. / #hallenge of an aortion law that required a physician to inform

a woman planning to have an aortion aout the nature of the procedure, health ris0s, proaly gestational age

of the child at least G9 hours prior to the procedure.

o Reaffirms the central legal principle of $oe, that a woman has a fundamental privacy interest in

controlling her reproductive autonomy. &owever, aandons the trimester approach as outdated and no

longer supportale y medical 0nowledge.

*irect abortion restrictions: *nstead, focuses on the 3tate+s interest on the potential human life.

&olds -'. that the point of viaility is the point at which the 3tate+s interest in life can outweigh

the mother+s autonomy rights.

$egulating abortion pre-viability: 1dopts the 4ndue 5urden 3tandard to apply to measures other

than outright ans on aortion / unconstitutional where a state regulation has the purpose or

effect of planning a sustantial ostacle in the path of a woman see0ing an aortion of a

nonviale fetus.

o 4ndue urden standard in action:

#n)ormed consent / ?verrules prior cases that struc0 down statutes that required physicians give

truthful, nonmisleading information prior to an aortion procedure -when designed to dissuade

the mother from continuing.. 3tate can enact legislation to ensure the decision is mature and

informed, even when the policy is clearly to encourage childirth rather than aortion. -?R.

Mandatory +,-%our waiting period / Required reflection period not unreasonale. %inds the fact

that some women must travel long distances to get an aortion, and may not e ale to afford two

trips, to e a closer question, ut in the end finds that it is not a sustantial urden. -?R Oon

these factsP.

5ut even for very serious surgeries, the state does not require such a waiting period.

Really, the state is attempting to discourage women, hope that a certain percentage of

women would change their minds.

<E

#onscious effort y the state to discourage a citi7en from exercising a fundamental

constitutional right. *s this o0ay'

o The plurality says yes. *t is a urden, ut not an undue one.

o 3tate is protecting its interest in the potential life. #an vindicate that right y

ma0ing sure the woman is sufficiently sure that she wants to exercise that right.

o 3tate can discourage citi7ens from exercising a wide variety of constitutional

rights: ;x. Right to assemly urdened y a pulic awareness campaign designed

to discourage 8eo-8a7i memership.

#oncerning the travel urden, the #ourt loo0ed to the record and the findings of fact. ?n

this record they found that it was not an undue urden. Thus, it left open the possiility

that in other places the urden could e too great. -''.

Thus, it is a fact-ased inquiry. 1ny new aortion law will e litigated in the courts.

!pousal noti)ication / #ourt pointed to the prevalence of domestic ause as a reason the spousal

notification provision created a sustantial ostacle. -45.

5ut what aout the !udicial ypass procedure'

o 1use / could e under the psychological control of a physically ausive

husand, so such attered women would not e ale to ma0e such a statement. *n

addition, there is veral and psychological ause, which is not accounted for y

the statute. 1lso, ased on fact-findings.

o Aomen+s rights / more recognition of the women+s rights aspect of the aortion

deate. &usand can have a sort of de facto veto power through psychological or

socio-economic control. *nforming him would e a great urden on the woman+s

decision.

Parental noti)ication / 1ffirmed past rulings that a 3tate may require a minor see0ing an aortion

to otain the consent of a parent or guardian, provided there is an adequate !udicial ypass

procedure. -?R.

-iling and documentation re.uirements / all permissile as in the interest of health research and

trac0ing. 2atient+s name is confidential. -?R.

34((1RN: 3plit the difference. &ad to stri0e one provision and uphold another to usher in a new era of

alancing and stri0ing a alance in the constitutionality of aortion law.

o 3tevens #)6 in part / Aould have struc0 the G9-hour waiting period and disclosure requirements.

o 5lac0mun #)6 in part / Aould 0eep $oe+s trimester framewor0 and strict scrutiny, ut was clearly

pleased that it was not overruled entirely.

o Rehnquist -Q>. #)6 in part / 2oints out the !oint opinions tortured application of the stare decisis and the

fact that the new standard for review was made out of whole cloth. 5elieve that $oe should e

overturned as not in tune with pulic sentiment and an un!ustifiale incursion into the legislative process.

Two ma!or issues from Casey:

o Ahat are the doctrinal rules governing aortion rights under #asey'

o Aas the 3upreme #ourt correct to invo0e the doctrine of stare decisis and not overturn Roe'

*ssue V< / 6octrinal rules governing aortion rights under #asey

o Reassures that there is a 362 right to privacy and to aortion. 5ut it is not unqualified and can e su!ect

to the state+s interest in preserving life.

o 3tate can prohiit aortions -except where the mother+s health is at ris0. from the point of viaility. That

is the point of independent existence of another life. 8o longer ound to the rigid trimester framewor0,

so whenever viaility happens is the point when the state+s compelling interest 0ic0s in.

o *n protecting the health of the mother and the potential life of the fetus, the state can ta0e steps to

encourage irth over aortion )rom *ay /, ut cannot create an undue urden on the right to aortion.

Ahat 0ind of test is this' 3trict scrutiny' *t doesn+t seem so harsh as that.

(ore li0e an intermediate scrutiny level of analysis. &ow strong or wea0 is difficult to tell.

5alancing test. -1nd for this uncertainty, the dissenters attac0 the opinion..

<=

The fundamental right of the mother+s privacy clashes with the primary interest of the state in

protecting the potential life of the fetus. Thus, it is not li0e most cases of infringement of a

fundamental right, where the countervailing state interest is usually not so strong.

5ut the undue urden test gets only 3 sure votes for the test.

3tevens uses the language undue urden ut he elieved that the test should e closer

to the strict scrutiny side.

5lac0mun elieves strict scrutiny should e applied.

The other 9 !ustices elieve $oe should e overturned and the 3upreme #ourt should get

out of the aortion regulation usiness.

o Ahat to do with a fractured court'

Ta0e the position with which at least I people agree.

;xtreme example

9 elieve aortion should e anned, < in the middle, 9 elieve aortion is an asolute

right.

*n this situation, if the middle person writes an opinion that incorporates parts of oth

views, that sole !ustice+s opinion will control with respect to all issues. Ahere lone !ustice

sides with the pro-lifers, that will have I votes. Ahere s,he sides with the other side, the

opinion has I votes too.

*n Casey, the !oint opinion gets at least I !ustices to agree that some of the procedures amount to

an undue urden. Ahile two of the !ustices elieve that a higher standard should e applied, the

agree at least that the state regulations at issue unduly urden the right to aortion. Thus, the

position of > !ustices of the !oint opinion -with the help of G pro-Roe !udges. trump the 9

dissenting !udges.

*ssue VG: #orrect to invo0e the doctrine of stare decisis and not overturn Roe'

o "ierty finds no refuge in a !urisprudence of dout.

"ierty depends upon a certain amount of certainty in the fundamental rights of citi7enship. *f

you never 0now when the court will ta0e away a particular right. Aill always e insecure aout

whether.

Aith that quote, the #ourt invo0es the doctrine of stare decisis.

o $enerally, state decisis has the most weight in commercial law. 1cts to protect the reasonale reliance of

commercial actors. Aould e profoundly wasteful and unfair. *n some situations, it is etter to leave the

law settled, than to get the law right@

o 5ut is there that type of reliance on the holding of $oe v. 0ade'

6e-legitimi7es the aortions already had. 10in to a -retrospective. !udicial determination that

these women were criminals at the time they had the aortion. 3tigma.

#ultural reliance / society has relied upon having the option of terminating a pregnancy. Aomen

expect to have control over their reproductive destiny and thus they advance their careers and not

have their professions

#ourt claims that the doctrine of stare decisis is especially important where grave, highly

controversial constitutional issues are decided.

Rehnquist states that this is ac0wards. #onventional wisdom is strong s.d. in statutory

interpretation -#ongress can always amend if the courts get it wrong.. Ahere as for

constitutional issues, s.d. should have a wea0er effect ,c a wrong decision is impossile

to overturn except with a constitutional amendment.

(a!ority agrees that this is true as a general matter. 5ut for the loc0uster issues must e

aggressive with s.d. ?therwise the #ourt will lose its legitimacy. Ahy'

o *t would undermine the #ourt+s legitimacy in the eyes of the nation if it was in

the usiness of overturning such loc0uster decisions. "egitimacy in the eyes of

the people is crucial to maintaining the power of the court@

o 2eople have accepted the power of the court to protect the interests of the

minority. %ollow the decisions ,c we respect the right of the court to have the

final say. 5ut that legitimacy turns entirely on the perception of the people that

<J

the court is ehaving neutrally, interpreting the law, not playing politics. %or that

reason the #ourt has to e extremely careful not to issue opinions that cause

people to question its legitimacy.

o #oncern that overruling Roe may simply lead to a new pro-choice appointment

that would overrule that case, and so on. 3oon people would reali7e that the

#ourt is not neutral, ut political !ust li0e the legislature. (ust guard the non-

political nature of the !udicial ranch. 2lacing the law over political views.

3calia ) Thomas agree that the 3upreme #ourt needs to e concerned aout its

legitimacy. That is why they elieve the #ourt should get out of the aortion regulation

usiness.

o 5ut what is more important: $etting it right' ?r protecting the legitimacy of the #ourt'

*s this case any different from 1rown v. 1d o) 2duc or 0est Coast otel'

Rehnquist: 8o difference.

Coint opinion: 8ot the type of fundamental change in factual, legal, or societal conditions

to warrant such a rea0 in stare decisis

o *n those cases, there was a lac0 of understanding of the factual underpinnings of

the !udicial reasoning. The legal reasoning was permissile has the situation

actually panned out as the !udges had thought: that separate facilities could not e

created equal, that laise77 fare economics would not ma0e corrections for the

poverty and generally e detrimental to society.

o 2lus law evolved enough such that the legal principles surrounding those

decisions had change so that those decisions no longer fit in.

o 3ocietal views on this issue have remained remar0aly consistent.

5ut the !oint opinion discards the trimester framewor0, so was stare decisis actually applied' #an

the 3upreme #ourt invo0e stare decisis and overrule a slew of cases at the same time'

&iding ehind the doctrine of stare decisis to deflect criticism' 4n!ustified application of

stare decisis'

o 8o. Reeps the core of $oe, that a fundamental right exists, ut !ettisons the parts

that have een undermined y later developments. %actual underpinnings of the

trimester system had ecome osolete, so only that part of the opinion should e

overruled.

o $rounds the right of aortion in autonomy and odily integrity. (ore explicit in

this regard.

o $ives a more detailed, less conclusory, history of the right to autonomy in

matters of family and privacy. *ncorporates the woman+s rights aspect of the right

to terminate pregnancy.