Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Ogle

Caricato da

Wahyu Sendirii Disinii0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

138 visualizzazioni8 paginethis book is about KWL

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentothis book is about KWL

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

138 visualizzazioni8 pagineOgle

Caricato da

Wahyu Sendirii Disiniithis book is about KWL

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 8

K-W-L: A Teaching Model That Develops Active Reading of Expository Text

Author(s): Donna M. Ogle

Source: The Reading Teacher, Vol. 39, No. 6 (Feb., 1986), pp. 564-570

Published by: International Reading Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20199156 .

Accessed: 17/07/2011 18:47

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at .

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ira. .

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

International Reading Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The

Reading Teacher.

http://www.jstor.org

K-W-L: A

teaching

model

that

develops

active

reading

of

expository

text

This

simple procedure helps

teachers become

more

responsive

to students'

knowledge

and interests when

reading expositor];

material,

and it models

for

students the active

thinking

involved

in

reading for information.

Donna M.

Ogle

Prior

knowledge

is

extremely impor

tant in

influencing

how we

interpret

what we read and what we learn from

reading (Anderson, 1977).

To read

well,

we must access the

knowledge

we

already

have about the

topic,

or

make it available

appropriately

so that

comprehension

can occur

(Anderson

and

Pichert, 1978; Bransford, 1983).

Despite

the research

highlighting

the

importance

of this

prior knowledge

and

many

calls for more interactive

teaching,

the

reading "scripts"

used for

teaching

children to read in schools too

often

ignore

the

importance

of what

the children

bring

to

reading.

Teachers

are instructed to

begin by telling

chil

dren the

gist

of what

they

are

going

to

read about and

why they

should read

this

particular

information. Even when

there are directions for teachers to find

out what the children

already

know

about the

topic,

teachers often over

look this instruction. As Durkin's

classroom observations demonstrated

(1984),

the most

neglected part

of

reading

lessons is that which instructs

teachers to elicit children's

background

knowledge.

To

help

teachers honor what chil

dren

bring

to each

reading

situation

and model for their students the

impor

tance of

accessing appropriate

knowl

edge

sources before

reading,

we have

developed

a

simple procedure

that can

be used with nonfiction selections at

any grade

level and in

any content,

whether in

reading groups

or in con

tent

learning

situations.

We have found that the

simplicity

of

instructional demands on

them makes

teachers

readily try

out this

technique

and then

incorporate

it into their

regu

lar routines.

(See Duffy

for a

descrip

564 The

Reading

Teacher

February

1986

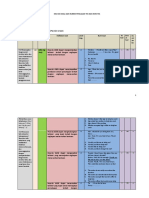

K-W-L

strategy

sheet

K?What we know

W?What we want

to find out

2.

Categories

of information we

expect

to use

A. E.

B. F.

C. G.

D.

L?What we learned and

still need to learn

tion of this

need, 1983.)

The

response

of children to the

technique

has been

most

enthusiastic,

and informal evalu

ations

by

teachers have confirmed for

teachers the

power

of this

simple pro

cedure.

A

logical three-step procedure

We have named this

three-step proce

dure the K-W-L for the three basic

cognitive steps required: accessing

what I

Know,

determining

what I Want

to

learn,

and

recalling

what I did Learn

as a result of

reading.

To facilitate both

the

group process

and to instill in stu

dents the concreteness of the

steps,

we

developed

a worksheet

(see

sample)

that each child uses

during

the think

ing-reading process.

For the first two

steps

of the

process

the teacher and students

engage

in oral

discussion followed

by

students'

per

sonal

responses

on their worksheets.

In the third

step

students can either fill

out the "What I learned" section as

they

read or

do so

immediately

follow

ing

the

completion

of the

article;

the

discussion follows the individual re

sponses.

In

long

articles the teacher

may

re

flect with students section

by section,

reviewing

what has been learned and

directing questions

for further

reading.

Step

K-What I know. This

opening step

has two levels of access

ing prior knowledge.

(1)

The first is

a

straightforward

brainstorming

of what the

group

knows about the

topic

for

reading.

During

this

step

the teacher's role is to

record whatever the students volunteer

about the

topic

on the board or an

overhead

projector.

The critical com

ponent

here is to select a

key concept

for the

brainstorming

that is

specific

enough

to

generate

the kinds of infor

mation that will be

pertinent

to the

reading.

For

example,

when the class will

read about sea

turtles,

use the words

sea turtles as the

stimulus,

not "What

do

you

know about animals that live in

the sea?" or "Have

you

ever been to the

ocean?" A

general

discussion of

enjoy

able

experiences

on the beach

may

never elicit the

pertinent

schemata.

The

brainstorming

that

precedes

reading

needs to have as its

goal

the

activation of whatever

knowledge

or

structures the readers have that will

help

them

interpret

what

they

read.

If there

appears

to be little knowl

edge

of sea turtles in

your

students' ex

perience,

then ask the next more

general question,

"What do

you

know

about turtles?" At this level no

group

will lack

knowledge.

As students vol

unteer

information, you

can

help

them

begin

to

question

if the

knowledge

or

information shared is true of all turtles

or

only specific

kinds.

K-W-L: A

teaching

model 565

The stimulation of

questions,

of un

certainties,

is a

key part

of the brain

storming

that

goes

on

prior

to

reading.

All of us

carry

around some

vague

and

ill defined

schemata;

opportunities

to

talk about what we think we

know,

to

put

our bits of

memory

into order can

really help

us discover what we don't

know.

The

way

of

deepening

student think

ing during

this initial

brainstorming

is

to ask

volunteers,

after

they

have made

their

contributions,

"Where did

you

learn that?" or "How could

you prove

that?"

By

not

simply accepting

the

statements that students offer but

prob

ing

to make them think about the

sources and substantiveness of their

suggestions,

you challenge

both con

tributors and the rest of the class to a

higher

level of

thinking.

This extended

questioning

also

helps

other students

feel freer to

provide contradictory

pieces

of information that can then be

confirmed

through

the

reading.

(2)

The second

part

of the brain

storming (or eliciting

what is

already

known)

that will be useful to students

in

reading

involves them in

thinking

of

the more

general categories

of infor

mation

likely

to be encountered when

they

read. We

say

"Before we read this

article on sea

turtles,

let's think awhile

about what kinds of information are

most

likely

to be included. Look at this

list of

things

we

already

know: Do

some of them fit

together

to form a

general category

of information?"

When teachers and students

begin

using

the K-W-L

they

often find this

question perplexing; they

are unaccus

tomed to

being

asked to think in con

tent-structuring

terms. To

help

them

begin

to think in these

categorical

terms,

we

begin by modeling

one or

two

examples

from the information

they

have

already generated.

For

example,

the teacher

might say

"I see three different

pieces

of informa

tion about how turtles look.

Descrip

tion or looks is

certainly

one

category

of information I would

expect

this ar

ticle to include."

(S/he

then writes this

category description,

or "how sea tur

tles

look,"

under the

Categories

of In

formation

heading.)

The teacher

proceeds,

"Can

you

find another cate

gory

from the information we've vol

unteered?"

After some oral

modeling

and exam

ples,

students

generally begin

to think

of

categories

that can be added to the

list. If

they

do

not,

the teacher has

good diagnostic

data about their readi

ness for this level of

thinking. Having

students read similar articles will

help

them

begin

to build a

background

un

derstanding

for the content area that

can serve them in their future

reading

and

learning.

For

example,

if students can't

gener

ate

likely categories

to be included in

an article on sea

turtles,

studying

other

articles on animals will

help

them

identify

and

anticipate key categories:

description,

care and nurture of

young,

enemies, habitat,

protective

devices,

eating

habits,

and

special

characteris

tics that

distinguish

it. Children can

then use this

knowledge

of

general

cat

egories

of information to store their

new

specific

data about whatever ani

mal

they

are

studying.

Step

W-What do I want to

learn? As students take time to think

about what

they already

know about

the

topic

and the

general categories

of

information that should be

anticipated,

questions emerge.

Not all students

agree

on the same

pieces

of informa

tion;

some information is

conflicting;

some of the

categories

have had no

particular

information

provided.

All this

prereading activity develops

the students' own reasons for

reading

?

reading

to find answers to

questions

that will increase their reservoir of

knowledge

on this

topic.

The teacher's

role in this

stage

is central. S/he must

highlight

their

disagreements

and

gaps

in information and

help

the students

raise

questions

that focus their atten

566 The

Reading

Teacher

February

1986

tion and

energize

their

reading.

The

majority

of

Step

W is done as a

group activity,

but before students be

gin

to

read,

each writes down on his/

her own worksheet the

specific

questions

that he/she is most interested

in

having

answered as a result of the

discussion. In this

way

each student

develops

a

personal

commitment that

will

guide

the

reading.

Once each student has focused

per

sonally

on this

topic, reading

may

commence.

However,

if it is a

long

ar

ticle or one that does not follow a basic

pattern,

it

may

be useful to

preview

the

article to discern the match between

the students'

expectations

and the ac

tual construction of the article. Then

difficult

or

unclear sections

may

be

noted for them.

Again, depending

on the

length

and

complexity

of the

article,

it

may

be

read in one

piece

or with some inter

mediate

steps

for reflection.

Step

L-What I learned. After

completing

the

article,

direct the stu

dents to write down what

they

learned

from

reading.

Have them check their

questions

to determine if the article

dealt with their concerns. If

not,

sug

gest

further

reading

to fulfill their de

sires to know. In this

way, you

are

setting

the clear

priority

of their

per

sonal desire to learn over

simply taking

in what the author has chosen to in

clude.

Each reader should have the

oppor

.

tunity

of

having

his/her

questions

an

swered or at least addressed. This is

what

reading

is

really

about!

By

hav

ing specific questions prior

to

reading,

students can also better

judge

the kinds

of variations that do exist in different

articles

they

read. Some will be more

pertinent

to their

particular

concerns

than others and it is

good

for students

to

develop

more critical awareness of

the limitations of all author-reader in

teractions. Readers need to be in

charge

in their

learning

and

actively

pursue

their own

quest

for

knowledge.

Transcript

of a K-W-L lesson

To make more concrete how the

proc

ess

actually

works, part

of a

transcript

from a fourth

grade

lesson is included

here. The article

being

read,

"The

Black

Widow,"

came from a children's

magazine.

It was

being

read as

part

of

a unit on

animals.

Teacher:

Today

we're

going

to read an

other article about animals. This one

is about a

special

kind of

spider?the

Black Widow. Before we

begin

the

article,

let's think about what we al

ready

know about Black Widows. Or

if

you

aren't familiar with this kind

of

spider,

think about some

things

you

know about

spiders

in

general,

and we can

then see if those are also

true for the Black Widow.

[Teacher

writes Black Widow

spider

on the

board and waits while students think

about their

knowledge

of

spiders.

Next she elicits ideas from children

and writes their contributions on the

board.]

Tony: Spiders

have six

legs.

Susan:

They

eat other insects.

Eddie: I think

they're big

and

danger

ous

spiders.

Teacher: Can

you

add more about what

you

mean when

you say they're big

and

dangerous?

Eddie:

They, they,

I think

they

eat

other

spiders.

I think

people

are

afraid of

them,

too.

Steph: They spin

nests or webs to

catch other insects in.

Tom:

My

cousin

got stung by

one once

and almost died.

Teacher: You mean

they

can be dan

gerous

to

people?

Tom:

Yah, my

cousin had to

go

to the

hospital.

Teacher: Does

anyone

else know more

about the Black Widow?

Tammy?

Tammy:

I don't think

they

live around

here. I've never heard of

anyone

be

ing stung by

one.

Teacher: Where do Black Widows

live? Does

anyone

know?

[She

waits.]

What else do we know about

K-W-L: A

teaching

model 567

spiders?

John: I think I saw a TV show about

them once.

They

have a

special

mark on their back. I think it's a blue

triangle

or

circle,

or

something

like

that. If

people

look,

they

can tell if

the

spider's

a Black Widow or not.

Teacher: Does

anyone

else recall

any

thing

more about how

they

look?

[She waits.]

Look at what we've al

ready

said about these

spiders.

Can

you

think of other information we

should add?

John: I think

they

kill their babies or

men

spiders.

I'm not sure which.

Teacher: Do

you

remember where

you

learned that?

John: I think I read an article once.

Teacher:

OK,

let's add that to our list.

Remember,

everything

on the list we

aren't sure of we can doublecheck

when we

read.

Teacher:

Anything

more

you

think

you

know about these

spiders? [She

waits.] OK,

before we read this ar

ticle let's think awhile about the

kinds or

categories

of information

that are

likely

to be included. Look

at the list of

things

we

already

know

or have

questions

about. Which of

the

categories

of information have

we

already

mentioned?

Peter: We mentioned how

they

look.

Teacher:

Yes,

we said

they're big

and

have six

legs.

And someone said

they

think Black Widows have a col

ored mark on them.

Good,

descrip

tion is one of the main

categories

of

information we want to learn about

when we read about animals or in

sects. What other

categories

of in

formation have we mentioned that

should be included?

Anna: Where

they

live;

but we aren't

sure.

Teacher:

Good,

we should find out

where

they

live. What other kinds of

information should we

expect

to

learn from the article? Think about

what kinds of information we've

learned from other articles about an

imals.

Diane: We want to know what kind of

homes

they

make.

Raul: What do

they

eat?

Andy:

How

they protect

themselves.

Cara: How do

they

have babies? How

many

do

they

have?

Teacher: Good

thinking.

Are there

other

categories

of information we

expect

to learn about.

[She waits.]

We've

thought

about what we al

ready

know and what kinds of infor

mation we're

likely

to learn from an

article on Black Widow

spiders.

Now what are some of the

questions

we want to have answered? I know

we had some

things

we weren't sure

about,

like where these

spiders

live.

What are some of the

things you'd

like to find out when we read?

Cara: I want to know how

many baby

spiders get

born.

Rico: Do Black Widows

really

hurt

people?

I never heard of

that,

and

my

dad knows a lot about

spiders.

Andy: Why

are

they

called Black Wid

ows? What's a widow?

Teacher: Good

question!

Does

anyone

know what a widow is?

Why

would

this

spider

be called a "Black

Widow"?

[After eliciting questions

from sev

eral

students,

the teacher asks each

child to write their own

questions

on

their

worksheet.]

What are the

ques

tions

you're

most interested in hav

ing

answered? Write them down

now. As

you read,

look for the an

swers and

jot

them down

on

your

worksheet as

you go,

or other infor

mation

you

don't want to

forget.

[The

students read the

article.]

Teacher: How did

you

like this article?

What did

you

learn?

Raul: The Black Widow eats her hus

band and sometimes her babies.

Yuck! I don't think I like that kind of

spider!

Steph: They

can live here ?it

says they

live in all

parts

of the United States.

Andy: They

can be

recognized by

an

568 The

Reading

Teacher

February

1986

hourglass

that is red

or

yellow

on

their abdomen.

Teacher: What is another word for ab

domen*}

[She waits.] Sara,

please

look

up

the word abdomen. Let's

find out where the

hourglass shape

is located. While Sara is

looking

that

word

up,

let's check what we learned

against

the

questions

we wanted an

swered. Are there some

questions

that didn't

get

answered? What more

do we want to know?

And so the discussion

goes

on,

helping

children relate what

they already

knew

about

spiders

and animal articles

gen

erally

to what was included in the ar

ticle

they

read in class.

The teacher also

helps

students

keep

the control of their own

inquiry,

ex

tending

the

pursuit

of

knowledge

be

yond just

the one article. The teacher

is

making

clear that

learning

shouldn't

be framed around

just

what an author

chooses to

include,

but that it involves

the identification of the learner's

ques

tions and the search for authors or ar

ticles

dealing

with those

questions.

Indications that K-W-L works well

Does this

strategy

for

group

instruc

tion

really

work? Does it

help

children

become more interactive readers and

help

them learn more as

they

read?

Positive answers to these

questions

have come from a

variety

of informal

evaluations done

by

teachers with

whom we have worked. Because we

wanted the teachers to

engage

in their

own

evaluations,

we made

suggestions

for evaluation and asked them to con

struct

ways

to evaluate the K-W-L.

One of the

simplest

forms of evalua

tion teachers used was to ask students

at the end of the term which of the ar

ticles

they

had read

they

remembered.

The

followup probe

asked

specifically

what

they

recalled

learning.

Over

whelmingly,

the articles and resource

materials

taught using

the K-W-L are

well remembered and recalled.

One

principal

who was involved in

the

training

of her teachers

using

this

strategy

interviewed students at the

end of the term herself. She was

amazed

by

the

high

level of recall of all

the articles the teacher had taken time

to

develop using

the K-W-L

strategy.

Now in answer to

questions

about the

amount of time the

strategy took,

she

confidently

answers that if we want the

students to learn the

content,

then it

isn't time

consuming

at

all;

other strat

egies

too often leave

no evidence of

learning.

Other teachers have

kept

the stu

dents' worksheets from the

beginning

of the

year

and then

compared

them to

work done later

on,

to evaluate the

changes.

These

comparisons

have

been valuable for

they

demonstrate

both that students are more able to

elicit their own

prior knowledge

with

experience

and that

they

can use writ

ing

as a useful

adjunct.

The worksheet

analyses

also demon

strate the

changes

in the kinds of con

tent

categories

students draw on.

Initially, asking

the

question

of what

categories

of information children ex

pect

drew blanks from

many

students

because

they

were so unfamiliar with

this kind of

thinking.

However,

with

experience

and

guidance

from their

teachers,

children's work made it clear

that

they

are

very capable

of

making

connections

among

the different kinds

of resources

they

have

already

availa

ble in their

experiences.

In

addition,

examples

from class

have

helped

them build a

better under

standing

of the

key categories

used

by

authors in

many

different fields.

Teachers noted much more

sophisti

cated

category

lists in the later work

sheets after

experience

with the

K-W-L.

Informal evaluation has also come

through analyses

of

videotapes

of

classrooms made at different

points

during

the

year. Tapes permit

teachers

to monitor both their own

development

in

teaching

and the

changes

in their

K-W-L: A

teaching

model 569

students.

Group processes

are hard for

teachers to reflect on as

they

occur,

so

the

videotape provides

a wonderful ret

rospective.

The number of students

participating generally

shows real

gains

over

time;

the

quality

of their

thinking improves;

and the involve

ment in and enthusiasm for

reading

nonfiction

goes

from lukewarm to re

ally

keen.

Perhaps

the

strongest

data

support

ing

teachers' efforts to use K-W-L in

their

teaching

came

directly

from the

children. Several teachers

reported

that their students asked them "Can we

do this article or

chapter

with the K

W-L?" When the teachers wouldn't

take the time to use the

process ap

proach,

students missed it! Other

teachers

reported

that students

began

to use the

strategy independently (ob

viously

the

goal

of

teaching)

when

they

were

reading

for content

learning

or

doing reports.

One teacher involved her students as

teachers of

younger

children to find

out how well

they

had learned the strat

egy. They

could use the basic

steps

and

help younger

children learn more ac

tively.

Another interviewed her chil

dren and asked them what

they thought

was

important

about the

way

she was

helping

them read. One to the

point

answer was "You think it is

important

what we

think;

not

just

what the book

says."

Without

exception,

the teachers

pi

loting

this

strategy

have

reported

that

when children have

questions they

are

reading

to

answer,

they

read

noisily

?

that

is,

when

they

come to

key

sections

of the

text,

they

often

unconsciously

but

audibly respond

with

"ahs," "ohs,"

and "ums."

This

strategy

has been

developed

so

that students can learn

through

the

classroom

group experience

how to be

come better

expository

readers. At the

same

time,

it has

taught

teachers more

about the interactive nature of

reading

and the

importance

of

personal

in

volvement

before,

during,

and after

reading.

K-W-L could use further

rigorous

evaluation.

However,

work with teach

ers has confirmed that it can be evalu

ated

by practitioners

in their own

classrooms without elaborate tests and

that it can

help

in our common at

tempts

to

produce

more

thoughtful

and

enthusiastic readers for the future.

Ogle

directs the Graduate

Program of

Reading

and

Language

Arts at Na

tional

College of

Education at Evan

ston, Illinois. She

developed

the

teaching strategy

described here

for

use in school districts in the

Chicago

area.

References

Anderson,

Richard C "The Notion of Schemata and the

Educational

Enterprise."

In

Schooling

and the

Acquisi

tion of

Knowledge,

edited

by

Richard C

Anderson,

Rand J.

Spiro,

and William E.

Montague. Hillsdale,

N.J.: Lawrence

Erlbaum,

1977.

Anderson, Richard

C,

and James W. Pichert. "Recall of

Previously

Unrecallable Information

Following

a Shift

in

Perspective."

Journal of Verbal

Learning

and Verbal

Behavior,

vol. 17

(February 1978), pp.

1-12.

Bransford,

John. "Schema Activation?Schema

Acquisi

tion." In

Learning

to Read in American

Schools,

edited

by

Richard C.

Anderson,

Jean

Osborn,

and Robert C

Tierney. Hillsdale,

N.J.: Lawrence

Erlbaum,

1983.

Duffy,

Gerald G. From Turn

Taking

to Sense

Making:

Class

room Factors and

Improved Reading

Achievement. Oc

casional

Paper

No. 59. East

Lansing,

Mich.: Institute

for Research on

Teaching, Michigan

State

University,

1983.

Durkin,

Dolores. "Is There a Match Between What Ele

mentary

Teachers Do and What Basal Reader Manuals

Recommend?" The

Reading Teacher,

vol. 37

(April

1984), pp.

734-44.

570 The

Reading

Teacher

February

1986

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Lesson Planning and Preservice Teachers: A Model For Implementing Research-Based Instructional StrategiesDocumento10 pagineLesson Planning and Preservice Teachers: A Model For Implementing Research-Based Instructional StrategiesDeeJey Gaming100% (1)

- Helping English Language Learners Succeed (Carmen)Documento172 pagineHelping English Language Learners Succeed (Carmen)Nurdiansyah Drinush Audacieux100% (1)

- Bhatt, Mehrotra - Buddhist Epistemology PDFDocumento149 pagineBhatt, Mehrotra - Buddhist Epistemology PDFNathalie67% (3)

- Case Study-Reflection PaperDocumento8 pagineCase Study-Reflection Paperapi-257359113Nessuna valutazione finora

- Most Likely To Harbor This Assumption Are Practitioners Who Have Been Heavily Immersed inDocumento6 pagineMost Likely To Harbor This Assumption Are Practitioners Who Have Been Heavily Immersed inNuno SilvaNessuna valutazione finora

- Reading Explorers Year 3: A Guided Skills-Based JourneyDa EverandReading Explorers Year 3: A Guided Skills-Based JourneyNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson 12 Developing Critical Thinking Skills Among Literature LearnersDocumento20 pagineLesson 12 Developing Critical Thinking Skills Among Literature LearnersJaira M. EscuetaNessuna valutazione finora

- Comprehension Instruction-What Makes Sense Now, What Might Make Sense SoonDocumento13 pagineComprehension Instruction-What Makes Sense Now, What Might Make Sense Soonbekgebas100% (1)

- Notes On Latin MaximsDocumento7 pagineNotes On Latin MaximsJr MateoNessuna valutazione finora

- Teaching Reading Theory 20 Copies PDFDocumento7 pagineTeaching Reading Theory 20 Copies PDFDN MukhiyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Teaching and Learning Strategies For The Thinking ClassroomDocumento50 pagineTeaching and Learning Strategies For The Thinking Classroomshamsduha100% (1)

- Reading Comprehension and Academic PerformanceDocumento9 pagineReading Comprehension and Academic PerformanceMelanieNessuna valutazione finora

- Midterm Exam in Assessment of LearningDocumento5 pagineMidterm Exam in Assessment of LearningNaci John TranceNessuna valutazione finora

- 3B Laugeson - The Science of Making FriendsDocumento47 pagine3B Laugeson - The Science of Making Friendslucia estrellaNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 3.ACTIVITIES - Listening PDFDocumento16 pagineChapter 3.ACTIVITIES - Listening PDFEsther Ponmalar Charles100% (1)

- Strategies To Enhance Reading ComprehensionDocumento7 pagineStrategies To Enhance Reading ComprehensionFamilia Brenes QuirosNessuna valutazione finora

- Cqm1 Cqm1h ManualDocumento75 pagineCqm1 Cqm1h ManualCicero MelloNessuna valutazione finora

- 10 0057 02 5RP AFP tcm142-701141Documento8 pagine10 0057 02 5RP AFP tcm142-701141riri.elysaNessuna valutazione finora

- Activating Prior Knowledge - PublishedDocumento3 pagineActivating Prior Knowledge - Publishedkevin roseNessuna valutazione finora

- Literature Review On KWL StrategyDocumento5 pagineLiterature Review On KWL Strategyequnruwgf100% (1)

- Anticipation Guides: Using Prediction To Promote Learning From TextDocumento6 pagineAnticipation Guides: Using Prediction To Promote Learning From TextHana TsukushiNessuna valutazione finora

- Educ 5312-Research Paper Template 1Documento9 pagineEduc 5312-Research Paper Template 1api-534834592Nessuna valutazione finora

- Reciprocal Teaching by Akashdeep KaurDocumento21 pagineReciprocal Teaching by Akashdeep KaurakashNessuna valutazione finora

- Summarizing StrategiesDocumento32 pagineSummarizing StrategiesFritzie AileNessuna valutazione finora

- Stem Annotation Template 2Documento6 pagineStem Annotation Template 2RECTO Elinnea Sydney H.100% (1)

- Educ 5312-Resea 3Documento7 pagineEduc 5312-Resea 3api-290458252Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson For Feb 26thDocumento4 pagineLesson For Feb 26thapi-311130965Nessuna valutazione finora

- Thinking Routines NGLDocumento5 pagineThinking Routines NGLDima ThanNessuna valutazione finora

- Bloom's Taxonomy Questioning: Discussion StrategiesDocumento13 pagineBloom's Taxonomy Questioning: Discussion Strategiesmgar10Nessuna valutazione finora

- Makalah Kelompok PsycholinguisticDocumento7 pagineMakalah Kelompok Psycholinguisticsidqy radinalNessuna valutazione finora

- KWL ChartDocumento8 pagineKWL Chart19911974Nessuna valutazione finora

- 6 Scaffolding Strategies To Use With Your StudentsDocumento5 pagine6 Scaffolding Strategies To Use With Your StudentsJack CoostoeNessuna valutazione finora

- Observation Lessons - HDocumento5 pagineObservation Lessons - Hapi-404203709Nessuna valutazione finora

- 1st Lesson Plan... The Community Garden..Documento6 pagine1st Lesson Plan... The Community Garden..OvalCatNessuna valutazione finora

- Ackground & Definitions: Exercises For Individual StudentsDocumento18 pagineAckground & Definitions: Exercises For Individual StudentsShah JoelNessuna valutazione finora

- Formative Assessment Strategies For Gathering Evidence of Student LearningDocumento7 pagineFormative Assessment Strategies For Gathering Evidence of Student LearningJohn Paul Viñas PhNessuna valutazione finora

- Strategy Notebook: Rachel HultsDocumento21 pagineStrategy Notebook: Rachel Hultsapi-271333426Nessuna valutazione finora

- Monitoring ComprehensionDocumento5 pagineMonitoring ComprehensionAndrea JoanaNessuna valutazione finora

- USF Elementary Education Lesson Plan Template: Read Aloud Name: - Lourdes - Rocha - Grade Level Being Taught: - 3rd - Date of Lesson: - 3/27/2019Documento6 pagineUSF Elementary Education Lesson Plan Template: Read Aloud Name: - Lourdes - Rocha - Grade Level Being Taught: - 3rd - Date of Lesson: - 3/27/2019api-449298895Nessuna valutazione finora

- Implement Interactive Read-Alouds for InclusionDocumento4 pagineImplement Interactive Read-Alouds for InclusionMerjie A. NunezNessuna valutazione finora

- K W L Research PaperDocumento15 pagineK W L Research PaperAhmad Shahir KamarudinNessuna valutazione finora

- Formative assessment strategies for gathering evidence of student learningDocumento5 pagineFormative assessment strategies for gathering evidence of student learningJonielNessuna valutazione finora

- Reciprocal Teaching: Submitted byDocumento43 pagineReciprocal Teaching: Submitted byakashNessuna valutazione finora

- Reading Methodology 2LG - StudentsDocumento14 pagineReading Methodology 2LG - StudentsmariepalmNessuna valutazione finora

- 912 Comprehension QARDocumento10 pagine912 Comprehension QARJohn Mureithi NjugunaNessuna valutazione finora

- Content Area ReadingDocumento30 pagineContent Area ReadingJohnjohn GalanzaNessuna valutazione finora

- 20 Reading Strategies For An Inclusive EFL ClassroomDocumento11 pagine20 Reading Strategies For An Inclusive EFL ClassroomDorina Vacari AndrieșNessuna valutazione finora

- Listening SamplesDocumento2 pagineListening SamplesemmasailyanNessuna valutazione finora

- Teaching Students Effective Reading and Writing Skills: A Guide To Being A History TADocumento8 pagineTeaching Students Effective Reading and Writing Skills: A Guide To Being A History TANotaly Mae Paja BadtingNessuna valutazione finora

- 1-Strategies To Enhance Reading ComprehensDocumento7 pagine1-Strategies To Enhance Reading ComprehensPANessuna valutazione finora

- Making InferenceDocumento4 pagineMaking InferenceLARISSANessuna valutazione finora

- ContentserverDocumento5 pagineContentserverapi-277412077Nessuna valutazione finora

- Karylle Sabalda-WPS OfficeDocumento2 pagineKarylle Sabalda-WPS OfficeKarylle SabaldanNessuna valutazione finora

- Rationale Theory: Common Misconceptions/ DifficultiesDocumento4 pagineRationale Theory: Common Misconceptions/ Difficultiesapi-356513456Nessuna valutazione finora

- Supervisor Observation 2 FinalDocumento8 pagineSupervisor Observation 2 Finalapi-312437398Nessuna valutazione finora

- Reading SkillsDocumento11 pagineReading SkillsAqsa ZahidNessuna valutazione finora

- Using Collaborative Strategic Reading: By: Janette K. Klingner and Sharon Vaughn (1998)Documento6 pagineUsing Collaborative Strategic Reading: By: Janette K. Klingner and Sharon Vaughn (1998)Hendra Nazhirul AsrofiNessuna valutazione finora

- 1Documento54 pagine1Maria Francessa AbatNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan Template: Essential QuestionDocumento4 pagineLesson Plan Template: Essential Questionapi-531359203Nessuna valutazione finora

- Teaching Reading in Social Studies Science and Math Chapter 8Documento13 pagineTeaching Reading in Social Studies Science and Math Chapter 8Azalia Delgado VeraNessuna valutazione finora

- Gradual Release of Responsibility 2Documento5 pagineGradual Release of Responsibility 2Plug SongNessuna valutazione finora

- Pre-Reading Activities: The Following Reading Activities Are Suited For High School LearnersDocumento22 paginePre-Reading Activities: The Following Reading Activities Are Suited For High School LearnersJunna Gariando BalolotNessuna valutazione finora

- Educ 5312Documento4 pagineEduc 5312api-667210761Nessuna valutazione finora

- Hard Copy ETMDocumento5 pagineHard Copy ETManis thahirahNessuna valutazione finora

- LP Trouble Dont Last 1213Documento3 pagineLP Trouble Dont Last 1213api-645821637Nessuna valutazione finora

- Theory of LearningDocumento11 pagineTheory of LearningkrithikanvenkatNessuna valutazione finora

- Ten Expression Giving Opinions To Use in Speaking and WritingDocumento1 paginaTen Expression Giving Opinions To Use in Speaking and WritingWahyu Sendirii DisiniiNessuna valutazione finora

- CL ChapterDocumento13 pagineCL Chapterdavidput1806Nessuna valutazione finora

- Presentation 1Documento13 paginePresentation 1Wahyu Sendirii DisiniiNessuna valutazione finora

- Module 3.collaborativeDocumento19 pagineModule 3.collaborativeWahyu Sendirii DisiniiNessuna valutazione finora

- Presentation 1Documento13 paginePresentation 1Wahyu Sendirii DisiniiNessuna valutazione finora

- Writing CompetenciesDocumento2 pagineWriting CompetenciesWahyu Sendirii DisiniiNessuna valutazione finora

- SQ3R Method - Reading TextbooksDocumento2 pagineSQ3R Method - Reading TextbooksWahyu Sendirii DisiniiNessuna valutazione finora

- Writing CompetenciesDocumento2 pagineWriting CompetenciesWahyu Sendirii DisiniiNessuna valutazione finora

- Formal Academic WritingDocumento2 pagineFormal Academic WritingWahyu Sendirii DisiniiNessuna valutazione finora

- Writing CompetenciesDocumento2 pagineWriting CompetenciesWahyu Sendirii DisiniiNessuna valutazione finora

- A2Documento2 pagineA2Norliyana IdrisNessuna valutazione finora

- Life As Ceremonial: By: M. Besant-ScottDocumento7 pagineLife As Ceremonial: By: M. Besant-ScottSheft-Hat Khnemu RaNessuna valutazione finora

- Advantages Disadvantages of DbmsDocumento3 pagineAdvantages Disadvantages of DbmsdunnkamwiNessuna valutazione finora

- Hilary Putnam - The Analytic and The SyntheticDocumento20 pagineHilary Putnam - The Analytic and The SyntheticCesar Jeanpierre Castillo GarciaNessuna valutazione finora

- Trend Download Software: Instructions For UseDocumento18 pagineTrend Download Software: Instructions For UseFredy7878Nessuna valutazione finora

- MGMT 222 Ch. V-1Documento30 pagineMGMT 222 Ch. V-1Asteway Mesfin100% (1)

- Oopt ScorecardDocumento1 paginaOopt Scorecardapi-260447266Nessuna valutazione finora

- C++ Program: All Tasks .CPPDocumento14 pagineC++ Program: All Tasks .CPPKhalid WaleedNessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento9 pagineUntitledLaith MahmoudNessuna valutazione finora

- Peter Sestoft KVL and IT University of Copenhagen: The TeacherDocumento8 paginePeter Sestoft KVL and IT University of Copenhagen: The TeacherArnaeemNessuna valutazione finora

- Passive VoiceDocumento2 paginePassive VoiceArni Dwi astutiNessuna valutazione finora

- Reading-Fluency K MTTESDocumento19 pagineReading-Fluency K MTTESRohit Sunil DeshmukhNessuna valutazione finora

- Paper ProcessorDocumento5 paginePaper Processororbit111981Nessuna valutazione finora

- Kisi-Kisi Soal - KD 3.1 - KD 4.1 - Kls XiiDocumento14 pagineKisi-Kisi Soal - KD 3.1 - KD 4.1 - Kls Xiisinyo201060% (5)

- Verilog Implementation, Synthesis & Physical Design of MOD 16 CounterDocumento5 pagineVerilog Implementation, Synthesis & Physical Design of MOD 16 CounterpavithrNessuna valutazione finora

- Sunday Worship ServiceDocumento19 pagineSunday Worship ServiceKathleen OlmillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Republic of the Philippines Oral Communication Diagnostic TestDocumento5 pagineRepublic of the Philippines Oral Communication Diagnostic Testmichelle ann sabilonaNessuna valutazione finora

- Write Your Answers A, B, C or D in The Numbered Box (1 Point)Documento70 pagineWrite Your Answers A, B, C or D in The Numbered Box (1 Point)A06-Nguyễn Yến NhiNessuna valutazione finora

- Positions by Derrida, Jacques - OpenTrolley Bookstore IndonesiaDocumento2 paginePositions by Derrida, Jacques - OpenTrolley Bookstore IndonesiaRiko Piliang0% (1)

- Module 1 and 2 Output Belison GroupDocumento4 pagineModule 1 and 2 Output Belison GroupMarie Nelsie MarmitoNessuna valutazione finora

- Literacy Narrative On Music PDFDocumento8 pagineLiteracy Narrative On Music PDFapi-315815192Nessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter-7 ArrayListDocumento33 pagineChapter-7 ArrayListdheeraj bhatiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lt1039 - Linear Tecnology-Rs232Documento13 pagineLt1039 - Linear Tecnology-Rs232Alex SantosNessuna valutazione finora