Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Digical Bain

Caricato da

billoukos0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

594 visualizzazioni16 pagineBain on the trend of Digical

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoBain on the trend of Digical

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

594 visualizzazioni16 pagineDigical Bain

Caricato da

billoukosBain on the trend of Digical

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 16

Leading a Digical transformation

The big change taking place in business today is the

combination of digital and physical elements to create

wholly new sources of value.

By Darrell K. Rigby and Suzanne Tager

SM

Darrell K. Rigby is a partner in the Boston office of Bain & Company and

leads the rms Global Innovation and Global Retail practices. Suzanne Tager

is senior director of Bains Retail and Consumer Products practices and is

based in New York.

Copyright 2014 Bain & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Leading a Digical

SM

transformation

1

The digital revolutions we have experienced in the last

few decades are nothing short of miraculous. In fact, the

changes have been so dramatic that some have predicted

the demise of physical commerce entirely. The retail guys

are going to go out of business, and e-commerce will

become the place everyone buys, declared Netscape

cofounder and venture capitalist Marc Andreessen. Author

Brett King argues that branch banks are headed the way

of book and record stores: By 2016, the average user

of banking services will be using digital services 300

times for every physical interaction with their bank. One

can imagine similar arguments about entertainment

(who needs movie theaters or concerts?), about routine

medical services (the doctor diagnoses your condition

through remote sensing and sends the prescription

to your e-pharmacy), and even about the production

and distribution of goods (dark factories and warehouses,

staffed entirely by robots).

And yet, straight-line extrapolations of digital dominance

miss some important insights. We humans are physical

and social beings. We like to go out, to interact in person

with other people, to touch and handle and make things.

Besides, any straight-line extrapolation assumes that

changes in the business ecosystem will continue pre-

dictably in the direction of the current curve, when in

fact rapid evolution creates unexpected opportunities

and new competitive dynamics. Look at movie theaters:

People have been predicting their demise for nearly 70

years. In principle, we could easily watch all of our movies

at home, streamed digitally to a big-screen TV. In practice,

theater owners and others in the business have devised a

variety of attractionsbetter seating, innovative projection

and sound technologies, full-service theater-restaurants

to lure us off our couches. US theater attendance has

declined a little over the last decade, but it is still nearly

three times as large as attendance at all theme parks and

major sporting events combined. Protable theaters will

almost certainly coexist with more home viewing in

the foreseeable future. You cant watch an IMAX in

your living room or on your mobile device (yet).

The truth is that both the digital world and the physical

one are indispensable parts of life and of business. The

real transformation taking place today isnt the replace-

ment of the one by the other, its the marriage of the two

into combinations that create wholly new sources of

value. This is a phenomenon we at Bain call Digical

SM

,

and it is likely to reshape not only the way people live,

but the way companies operate.

The Digical world

Digital-physical innovations are already changing virtually

every part of the business world. The effects are dramatic

in some industries and modest in others, but they are

hard to miss. Think for a moment about just a few of

the combinations that are now reality:

Travelers still rely on airplanes to visit a distant

city. But the reservation, ticketing and payment

system for the trip are all digital. So is the planes

control system. Face- and iris-scanners may soon

supplement human security personnel at airport

checkpoints. Such technology may eventually allow

airlines to eliminate the boarding pass completely,

according to the chief information ofcer of Lon-

dons Gatwick Airport.

Most healthcare today relies on physical interactions

combined with growing use of digital diagnostic

equipment and records management. But medi-

cine is expanding its Digical innovations. Intuitive

Surgicals da Vinci machines enable a mentoring

surgeon in New York or London to monitor every-

thing a less experienced surgeon in Johannesburg

is doing and draw guiding incision lines on the

surgical image from a remote interface. Local men-

tors with dual digital consoles can even take over

robotic control at especially critical points.

3-D printing, a digitally controlled process currently

used mainly for rapid prototyping, is finding a

variety of new applications. General Electric plans

2

Leading a Digical

SM

transformation

late 2013 its products were available in 80 Nordstrom

stores. Says Bonobos CEO Andy Dunn: What weve

learned recently is that the ofine experience of touch-

ing and feeling isnt going away.

The key questions for todays executives are how to

anticipate developments in this ongoing revolution and

how to lead the inevitable transformation. We recently

reviewed the experience of some 300 companies engaged

in Digical initiatives. Our sample covered a full range

of industries, from those that wont soon see much

digital-physical transformation, such as construction, to

those that have already been dramatically (and traumati-

cally) transformed, such as media. We examined compa-

nies at every stage of evolution within these industries,

and we carried out longitudinal studies of their transi-

tions over time to understand the changes and con-

ditions that led to positive and negative results. We also

reviewed the relevant literature and conducted inter-

views with executives in leading organizations.

The ndings point in one clear direction. Every industry

will undergo some degree of Digical transformation. Vir-

tually every company will have to respond. The threat is

great, but so is the opportunity: A strategy that fuses

the best of both digital and physical worlds is likely to

generate the greatest value for the foreseeable future.

Yet creating Digical products and developing Digical

capabilities requires sustained focus and the right

investments. You cant just add sensors to a product

or tweak your e-commerce capabilities. And in most

cases you cant simply switch sides, throwing away core

advantages while pouring resources into high-risk,

purely digital ventures with no clear competitive edge.

Lets look at how to begin.

Diagnosing your industry

Though Digical innovations will affect every industry,

theyll hit some businesses much harder and faster than

others. So a key rst step is assessing your companys

to use an advanced 3-D technique known as direct

metal laser melting to produce fuel nozzles for its

next-generation aircraft engine. Richard Van As, a

South African carpenter, worked with partners to

develop a mechanical robohand made from digitally

printed parts. One beneciary of Van Ass design

is a young man in Massachusetts who was born

without ngers on his left hand. His new prosthetic

cost about $150. The next-generation robohand,

refined through crowdsourcing via social media,

snaps together like LEGO bricks; the materials

cost about $5.

Smart homes learn user preferences and auto-

matically adjust utilities settings. Smart grocery

carts detect nearby items and show videos of meal

and recipe ideas in real time. Smart cars can detect

obstacles in the road and can help you park. Driver-

less cars are very much in the works. Audis robotic

car has journeyed to the top of Pikes Peak in Colo-

rado; Volkswagens has traveled down Berlin streets.

Google has many prototypes that as a group have

gone more than 600,000 miles without a seri-

ous accident.

This trend toward a Digical world will only intensify. The

much-heralded Internet of Thingssensors attached

to everything from electrical turbines to railroad cars

will digitally monitor performance and environmental

conditions in the physical world, boosting efciency

and minimizing unplanned downtime. Live entertain-

ment from rock concerts to theme parks will incorporate

more digital effects. Disney Worlds new MyMagic+

system, for example, provides visitors with a smartphone

app and a radio-frequency-enabled wristband that acts

as ticket, room key and credit card, allowing them to book

rides in advance and charge meals with a flick of the

wrist. Even companies built strictly on e-commerce are

coming to see the value of the physical dimension. The

e-retailer Bonobos, one among the many that are re-

thinking their priorities, has begun to open Guideshops

where people can try on the companys clothing, and in

Leading a Digical

SM

transformation

3

environment. How much has the ongoing transformation

already changed your industrys offerings and competitive

dynamics? How much is it likely to do so in the next

several years? Figure 1 captures Bains assessment of

Digical transformation for 20 different industries. You

can see at a glance some of our key ndings:

The impact ranges widely. Industries occupy remark-

ably different points on the transformation curve.

Change has been more than three times as extensive

in media, technology and telecom industries as in

oil and gas, mining and construction. Other indus-

tries are spread out across the curve.

The biggest change is yet to come. The next several

years will bring far more innovation to most indus-

tries than they have seen in the past. Automotive,

insurance and many other businesses are poised on

the verge of far-reaching Digical transformations.

Even todays early movers, such as telecom and retail

banking, are in for a lot more change in the future.

Wild cards can affect the pace of change. Some

industriesbut only somewill be held back by

external factors. Healthcare, in particular, wont

evolve as quickly as it otherwise might; regulations,

reimbursement practices and liability issues all

impede innovation.

The aggregate numbers, while telling, are only a start-

ing point. The challenge for any company is to analyze

each part of its industrys value chain and determine

which points are best suited to Digical innovation. In

construction, one such point may be site preparation.

(Caterpillar already produces earth-moving machinery

equipped with GPS and laser technology, allowing

operators to excavate to precise depths and slopes.) In

healthcare, opportunities for innovation may lie in the

Figure 1: Projected Digical transformation by industry through 2025

P

h

a

r

m

a

c

e

u

t

i

c

a

l

s

C

o

n

s

t

r

u

c

t

i

o

n

Slow-moving

Middle-of-the-road

Fast-moving

Total Digical transformation through 2025

M

e

d

i

a

T

e

c

h

n

o

l

o

g

y

T

e

l

e

c

o

m

R

e

t

a

i

l

b

a

n

k

i

n

g

R

e

t

a

i

l

A

i

r

l

i

n

e

s

A

u

t

o

I

n

s

u

r

a

n

c

e

H

o

t

e

l

s

&

r

e

s

t

a

u

r

a

n

t

s

E

d

u

c

a

t

i

o

n

M

e

d

t

e

c

h

H

e

a

l

t

h

c

a

r

e

p

a

y

e

r

s

&

p

r

o

v

i

d

e

r

s

L

o

g

i

s

t

i

c

s

&

t

r

a

n

s

p

o

r

t

a

t

i

o

n

C

o

n

s

u

m

e

r

p

r

o

d

u

c

t

s

U

t

i

l

i

t

i

e

s

O

i

l

&

g

a

s

M

i

n

i

n

g

M

a

n

u

f

a

c

t

u

r

i

n

g

The rankings are based on examination of more than 300 companies engaged in Digical projects, plus additional industry interviews. We calculated relative levels of

transformation based on our review of value chain impact and importance both today and in the futurethat is, which segments of the value chain are most important to success

in that industry and how much transformation has occurred and will occur in those segments.

Potential change limited by regulatory, legal, etc. Today Incremental through 2025

4

Leading a Digical

SM

transformation

they are making big investments in innovations. The

reason? Competitors are moving faster. Particularly in

industries that are changing quickly, many companies

run as fast as they think they can, only to nd that they

are falling further behind.

Responding to Digical innovation

Most companies nd it hard to respond successfully

to innovations of all sorts. Our study of 300 companies

found that not a single one was completely surprised

by the advent of Digical innovations, yet nearly 80% of

those companies are still in the early stages of response.

This probably shouldnt be surprising. Digital expertise

is still scarce in the senior ranks of many traditional

companies, so executives often fail to understand both the

threats and the opportunities. Confronted by unfamiliar

new technologies and competitive moves, some do their

best to ignore the threat; they convince themselves (and

seek reassurance from the rest of their team) that it wont

last or doesnt really mean much. Everything will be OK

as long as they keep doing a good job in their traditional

business. Others take the opposite tack, nervously over-

reacting to the hype that greets the innovation and then

placing outsized bets on strategies based on hunches.

In both cases the companies involved are likely to wind

up in trouble.

The most successful companies understand the need

to respond but recognize that the response will evolve

along with their experience and capabilities (see the

sidebar NIKE embarks on a Digical future). They

acquire and nurture the necessary expertise, often going

where the talent is (Silicon Valley, for example) rather

than expecting innovators to come to them. They keep

innovation units separate from the core business for a

while, so that those units can experiment and grow with-

out the constraints of a large organization. But they

also work at improving the core itself, understanding

that the core holds potential competitive advantages.

Eventually they bring the core and the innovators to-

delivery of chronic-care services. (Remote sensors and

monitors can help keep patients with chronic illnesses

at home and out of the hospital.) Look at the music busi-

ness, which many people believe has somehow died.

Recorded music is still a protable businessbut mostly

for Apple, which transformed how music is sold. Licens-

ing is still protable. Live concerts, augmented by dig-

ital technologies, are more profitable than ever. The

vulnerable part of the value chain was the conventional

method of producing and selling records.

The retail industry illustrates the scale of change that

lies ahead and the corresponding areas of opportunity.

Virtually every retailer has faced severe disruption from

pure-play online competitors, and many have already

spent hundreds of millions on building up their digital

marketing and e-commerce capabilities. But a long list

of other potential investments awaits: digitally en-

hanced customer service, interactive displays in stores,

advanced website improvements, supply-chain efcien-

cies, rapid fulllment, radio frequency identification

(RFID) tagging in stores and warehouses, mobile apps,

new point-of-sale systems, employee training and devel-

opment tools, mobile payment systems, advanced cus-

tomer relationship management analytics, IT systems

integration and security, and so on. Most retailers have

barely scratched the surface in these areas. Moreover,

the industrys disruptors have not played their last hand.

Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos, for example, has expressed an

interest in building physical stores. Should the company

gure out ways to reinvent the store along Digical lines,

that would represent one of the biggest threats yet to

traditional retailers.

What matters most to every company, of course, is how

fast it is moving relative to others in its industry. The

research rm L2, which calls itself A Think Tank for

Digital Innovation, calculates a digital IQ for compa-

nies in a variety of industries based on assessments of

hundreds of different variables. Some companies nd

that their scores actually drop over time, even though

Leading a Digical

SM

transformation

5

NIKE embarks on a Digical future

What could be more rmly rooted in the physical dimension than the leading sports apparel company

in the world? Yet NIKE has begun to create a broad-based Digical business, to the point where Fast

Company named it the No. 1 Most Innovative Company of 2013.

An early initiative was the companys NIKEiD customization program, launched in 1999. Buyers would

visit nike.com and customize certain NIKE shoes, choosing their own base and accent colors and

then adding a personal I.D. to the product. NIKE then began introducing Digical innovations at

other points in the value chain, creating links between company and consumers that went well beyond

the sale of a sweatshirt or a pair of shoes. In 2006, for instance, NIKE CEO Mark Parker and Apples

Steve Jobs unveiled the NIKE+ app, a product connecting the NIKE+ Air Zoom Moire, a shoe with

a built-in sensor and receiver, to an iPod Nano. Runners could see data about their time, distance,

calories burned and pace on the devices screen or hear it reported orally over their headphones.

After the workout, they could sync the iPod with their computers and chart their progress.

Today, more than 20 million members spanning the globe use the NIKE+ platform, tracking and sharing

runs, workouts and tness goalsand providing the company with invaluable data about who their

customers are and what they value most. NIKEs NIKE+ FuelBand and NIKE+ FuelBand SE, two models

of an electronic bracelet, take the post-sale involvement one step further. The FuelBands measure all the

users movements throughout the day, recording indicators such as steps taken and calories burned.

As with the shoe sensors and NIKE+ Running app, users can capture this data, track and record their

level of activity, and share the information through social media.

The company has found creative ways to integrate the digital and the physical not only in its products

but also in its go-to-market system. Preparing to launch its new NIKE Free Run+ 3 shoe in 2012, for

instance, NIKE rst offered it online to NIKEiD customizers, who responded by creating more than

a million designs in just two weeks. The resulting buzz created enormous momentum and high sell-

through when the NIKE Free Run+ 3 hit retail shelves, said company executive Christiana Shi.

Another example: the companys womens training club, a special section of NIKEs stores that

brings together products for women, services such as bra tting and shoe trying-out, and training

classesall to make it easier for her to nd, shop and buy the right product in a seamless way

across NIKE channels, according to Shi.

An important step has been NIKEs reorganization to foster these innovations, including establishing

a Digital Sport division in 2010 and creating a state-of-the-art e-commerce platform. The payoffs

include increased market share in key areas, a 32% growth in e-commerce sales from FY 2012 to

FY 2013 and a rising stock price, from below $40 in 2009 to nearly $80 in late 2013. NIKE

has broken out of apparel and into tech, data and services, which is so hard for any company to do,

one analyst told Fast Company.

6

Leading a Digical

SM

transformation

Executives at Beginner companies, we have found, are

often most concerned with developing new growth

options even as they exude complete confidence in

their traditional core businesses.

Danone is one company that may qualify as a pioneer

Beginner. Its industryconsumer packaged goods

has generally been slow to create Digical products or

embrace online channels, and in 2012 Danones director

of communications acknowledged that the company

was not really an early adopter of digital innovations.

At this writing, Danone has made initial moves into

digital marketing and social media, and it has announced

(but not yet released) a Wi-Fiequipped refrigerator magnet

that lets users set their preferences for bottled-water

delivery and then transmits the information wirelessly

to the deliverer. Danone has also created the position

of vice president of connection, media and innova-

tion, responsible for integrating its online and ofine

marketing efforts.

Intermediates. Typically, companies in the Intermediate

stage have already launched some Digical initiatives.

Instead of merely responding to threats from rivals,

they are out to beat the competition. If that requires

making big investments in new technologies or seek-

ing out new customers, so be it. The future may be

scary, but in an Intermediates view, it cant be avoided.

Though many Intermediates still have only average

infrastructure capabilities, they are testing and learn-

ing aggressively. Organizationally and culturally, they

view Digical goals with enthusiasm, though individual

units may be protective of their unique skills in this

area. Executives of Intermediate organizations often

create new performance metrics (such as loyalty or

market share of the most attractive Digical customers)

to focus the organizations efforts and build condence

in the new direction.

Macys provides a good example of an Intermediate.

As early as 2005 the retailing chain was investing heavily

in website and infrastructure capacity, and in 2010 it

gether, transforming the company and capitalizing

on those competitive advantages to create Digical inno-

vations of their own.

The timing and balance are delicate. Get the process

rightas companies such as Disney, Audi and Common-

wealth Bank of Australia seem to have doneand

the revitalized core continues to generate growth and

prots. Get it wrong and the organization sties the

innovations. Of course, some of the steps along the way

will be way stations; history will view them as transition

points, like the videocassette recorder. But from a com-

panys perspective, it hardly matters. Even if a new prod-

uct, organizational structure or mobile strategy turns out

to be transitional, it helps the company extend its core

business, generates cash to fund further transition and

builds capabilities that will be essential for future success.

So the response typically plays out over a period of years.

During that time, we have found, Digical innovators

in virtually every industry pass through three quite

different stages of development. Knowing which stage

you are in today can help you gure out the best rela-

tionship between your traditional business and your

new one. It can also help guide the right moves from

your current stage to the next.

Beginners. Most companies are just getting started.

They are still novices. But not all of these Beginners

are the same. Some are pioneersthey may be in a

slow-moving industry, but theyre hoping to lead their

peers into the Digical future. Others are laggards, late

to the party and now well behind the competition.

Despite their different situations, the two groups often

have a similar look and feel. Beginners are still guring

out how to experiment with new Digical fusions while

maintaining their core business. They are still trying to

identify their customers needs and frustrations. They

may be slow to innovate, and they are likely to have a lot

of money invested in older technologies. Their organi-

zation is probably siloed and their culture conservative.

Leading a Digical

SM

transformation

7

discipline required by a project. As they work, the teams

might rely on innovations such as the companys Digital

Immersive Showroom, or DISH, which uses high-de-

nition display walls and high-precision motion capture

to simulate a ride or other attraction.

Figure 2 offers some guidelines for each of the six ele-

ments that indicate whether a company is a Beginner,

Intermediate or Expert. Reading through the elements

labeled on the left-hand side can help you determine

which of the three category descriptions across the top

best ts your organization. If you put more than three

elements in one category, thats probably your best start-

ing point for choosing the right course of action.

Experts dont rest on their laurelsthey

realize that their own innovations face

constant threats from newer ones, and

they constantly push the limits of whats

possible. Digical is no longer an add-on;

it is part of the way they do business.

Determining where you want to goand how fast

you need to get there

Most companies naturally aim to move into a more

advanced stage of Digical development (se Figure 2).

They hope to outstrip competitors and eventually become

Expert. But the right moves for one company may be

wrong for another. Determining your Digical objectives

and mapping out an appropriate pace of change depend

greatly on your industry and situation (se Figure 3).

Consider how the very different experiences of Sears

and Macys reect the way that some moves succeed

while others backre.

mapped out an omnichannel strategy designed to create

a seamless experience for customers both online and in

stores. Recently, it has been pursuing a host of Digical

initiatives. It has integrated most of its online shopping

with its physical facilities, turning virtually all of its

stores into multichannel fulllment centers; customers

can order online and then pick up their items at a local

store. Its iconic Herald Square store in New York City

one of the largest department stores in the worldis

undergoing a $400 million remodeling; the renovated

store will feature Digical innovations such as interactive

directories, digital product information, widespread

use of RFID tagging and a new mobile app to guide

customers as they shop.

Experts. Companies that have reached the Expert stage

have usually been at it awhile. They perceive the pos-

sibilities of the Digical revolution, and they have moved

from competitor benchmarking to customer pathbreaking.

They have the integrated systems and tools required

to enable change, and they invent new capabilities as they

go. Organizationally, they are one team, with a unied

culture and few skill gaps. Typically, experts dont rest

on their laurelsthey realize that their own innovations

face constant threats from newer ones. As a result, they

constantly test new approaches and push the limits of

whats possible. Digical is no longer an add-on; it is part

of the way they do business.

Consider Disney, whose Imagineering unit has been rede-

ning theme-park entertainment for several decades.

Imagineering began combining digital and physical

experiences back when digital technology was clunky

and expensivea computer-controlled thrill ride (Space

Mountain, introduced in 1975), Audio-Animatronics

attractions (talking robotic gures) and so on. Over the

years it introduced everything from new virtual reality

technology to figures capable of interacting with an

audience (Turtle Talk with Crush, the laid-back dude

from Finding Nemo). Imagineerings 1,500 employees

typically work in teams that bring together architects,

engineers, software designers, artists and every other

8

Leading a Digical

SM

transformation

Figure 2: Companies occupy different stages of Digical development

Beginner Intermediate Expert

1- to 2-year time horizons

Cautious approach to test viability

with minimal investments

Heavy reliance on

competitor benchmarking

3-year time horizons

Accelerating market share gains and

profit improvements

Reducing pain points and improving

integration in current customer pathways

5+ year time horizons

Real expectations to redefine

the game

Innovation centered on customer

pathbreaking

Ambitions

Low-risk, proven approaches with

more fanfare than action

Narrow focus on a few steps of the

value chain (often marketing, sales

or operating costs)

Bolder testing and learning initiatives

Broader integration and innovation

of cross-functional interactions

Constant testing with greater secrecy;

highly anticipated breakthroughs

Encompass full customer journeys

Operating

strategies

Commitments to sunk costs and old

technologies impede progress

Focus on efficiency

Growing networks of pipes and people

enable greater change

Complicated accountabilities

State-of-the-art assets

Integrated systems and tools improve

quality, speed, efficiency and yield

of decisions

Infrastructure

Autonomous silos with separate metrics

Building uncomfortable new

capabilities; frequent outsourcing

Increasing coordination and more

matrixed relationships

Traditional core managers seek

greater control over Digical initiatives

Digical skills distributed throughout

the company

One team with unified culture and

world-class centers of excellence;

insourcing of core capabilities

Organization

Delegated to mavericks

Periodic inquisitions with

senior management

Major strategy projects viewed as

add-ons to day jobs

Changes focused on integration

Continuous strategy processes

A balanced portfolio of incremental

and breakthrough innovations

Transformation

management

Customer frustrations

Innovation laggard; frequent

unexpected potholes

Encouraging sales growth,

challenging profits

Fewer customer complaints

Occasional innovation breakthroughs

Digical innovation increases both top-

and bottom-line momentum

A loyal base of passionate advocates

Widely admired performance

Digical redefines the companys

source of value creation

Results

Leading a Digical

SM

transformation

9

Macys followed a different path, albeit with some bumps

of its own. The company launched Macys.com as part

of its Macys West division in 1996, and two years later

established the unit as a standalone subsidiary in Sili-

con Valley. The goal was to take full advantage of the

Internets continued emergence as a vehicle for con-

sumers shopping needs. Still, Macys was not an online

pioneer; Womens Wear Daily referred to its strategy

as a relative Johnny-come-lately. To accelerate its

efforts, the company paid $1.7 billion in 1999 for Finger-

hut, a direct marketer with several catalogs and e-com-

merce ventures. Analysts applauded the move, which

gave Macys access to Fingerhuts extensive database

marketing and fulllment skills. But by 2002 Macys

was announcing the divestiture of Fingerhut, citing its

lack of strategic value.

Macys then doubled down on innovation. In 2006 it

announced a $130 million investment in Macys.com,

followed by $100 million more in 2007. In 2010 it

announced a new omnichannel strategy. Finding that

customers who shopped both online and in stores

generated ve times the prot of those who shopped

only online, Macys aimed for greater integration. It

invested heavily in its physical outlets, not only the

Herald Square agship but hundreds of other stores

as well. It piloted the use of stores as distribution cen-

ters, shipping items direct to online buyers and lling

orders from stores when an item was out of stock in

online warehouses. It also invested in new training

and tools for sales associates as part of its MAGIC

Selling campaign, a program designed to encourage

associates to sell from the heart and to take the extra

step to make every customer feel special. In January

2013, the companys executive vice president for omni-

channel strategy assumed the newly created role of

chief omnichannel ofcer, reporting to the CEO. The

executive in the new position not only oversees the

development of strategies to integrate the companys

stores, online and mobile activities; he is also respon-

Sears jumped on the digital bandwagon early. In 1984

well before the World Wide Webthe retailer and two

partners created the online service provider that would

come to be known as Prodigy. As a company with a

once-thriving catalog business, Sears seemed well posi-

tioned to migrate catalog orders online. But the next

several years brought disappointment: Neither Prodigy

nor a subsequent partnership with AOL lived up to

expectations. As the e-commerce marketplace evolved,

Sears began losing market share to online sellers such

as Amazon.com.

Sears tried again under the leadership of Edward S.

(Eddie) Lampert, who bought a controlling interest in

the company in 2005. Lampert divided the company

into more than 30 independent business units, each

with its own functional heads, board of directors, nan-

cial statements and strategy. He also invested heavily

in Searss e-commerce business, creating what a Credit

Suisse analyst called a better website than just about

any other retailer I cover. In 2012 Lampert created a

vice president of customer experience and integrated

retail position in hopes of integrating its digital and

physical businesses.

In retrospect, however, the company appears to have

made at least two miscalculations. Searss radically

decentralized structure has been an obstacle to collab-

oration. And the company chose to underinvest in one

part of that integration equation: its stores. In 2012,

for instance, it spent an average of $1.46 per square

foot on its stores, compared with an average of $9.45

per square foot that four of its chief competitors spent

on theirs, according to the New York Times. Reports in

the mainstream media have referred to Searss neglected

stores. Profits fell, putting pressure on Web invest-

ments. Id like to go faster. Id like to go bigger, chair-

man Lampert told the Times in 2013. Were just not

making money, which makes it much, much harder

to fund the transformation.

10

Leading a Digical

SM

transformation

If you are a Beginner in a fast-moving industry, your

best option may be nding a partner. If you are an Expert

in a slow-moving industry, you are well positioned

but you have to be careful not to outrun your customers.

Companies in middle-of-the-road industries face perhaps

the most complex set of challenges and trade-offs (se

Figure 3). For example:

A Beginner in a middling industry has to stay

within striking distance of the leaders even as it

masters the basics. Like a trailing race car, it can

try to draft those leaders, following their path

while keeping a sharp eye out for opportunities

to pass. Among the keys: bringing the right talent

on board, investing to wow high-priority customer

segments and partnering with expert third parties.

Internally, the job is to raise the cultural speed

limitand to make sure that every executive is on

board for the journey.

sible for the companys systems and technology, logistics

and related operating functions. Unlike that of Sears,

the nancial performance of Macys has improved sig-

nicantly, and it has gained market share. Its stock rose

steadily between 2010 and 2013, increasing 43.1% in 2013

alone (compared with a gain in the S&P 500 of 28.5%).

How to account for the difference between the two re-

tailers? Both companies started out as Beginners. But

Searss one-sided investments had the effect of prolonging

its Beginner status, while the multifaceted approach of

Macys moved it into the Intermediate ranks. Neither

company has yet moved into the Expert box, but Macys

currently has a better chance of arriving there sooner.

The two chains experiences underscore a key point of

our analysis. Your current position presents you with

specic sets of challenges and opportunities, and you

ignore those challenges and opportunities at your peril.

Figure 3: Your next steps depend upon your companys situation

Beginner Intermediate Expert

Partner

or perish

Hasten innovation

and acquisitions

Lead customer

pathbreaking

Draft the leader(s),

seek to pass

Set breakout ambitions,

consider acquisitions

Amaze customers,

dispirit competitors

Build foundational

capabilities

Scale capability successes

to gain share

Avoid

outrunning customers

Slow-moving

Middle-of-the-road

Fast-moving

Company-development stage

Industry-evolution

stage

Leader/pioneer Parity Laggard

Leading a Digical

SM

transformation

11

represent the companys future. When youre confronted

with transformative innovations, its tough to be a

fast follower. If the table-stakes investment to keep

up with competitors is $1 billion a year for three years

but you try to get by with $500 million a year, by the end

of the three-year period you are $1.5 billion behinda

hole so deep that you cant climb out of it.

To prosper, a company needs to move fast enough to

stay ahead of competitors and get into the next stage.

Trying to jump a stage rarely works, but staying in the

same stage too long will put you out of the running.

Separation vs. integration. A second challenge is man-

aging the balance between separation and integration.

Separation of an innovative unit in the early phases of

development enables a more exible and entrepreneurial

culture, free to challenge the status quo and existing

business models. It helps a company attract and retain

top technology talent and develop deep expertise. A sep-

arate unit eliminates fears of cannibalization and permits

the establishment of highly motivational goals and incen-

tives. It increases a companys operating speed and cre-

ativity, and it generates more breakthrough innovations.

But in a Digical marketplace no company can keep

things separate forever. Customers expect a seamless

integration of both digital and physical experiences

the best of both worldsrather than the disjointed

and frustrating interactions that often come from

autonomous silos. And if the rst set of changes is suc-

cessful and the company moves into the next stage,

then the independent units will either largely replace

the traditional units or will use their successful experi-

ence to help transform the traditional business.

Integration brings a series of benets, including ef-

ciency and economies of scale, coordination and timely

communication, and less conflict. It avoids redun-

dancy and enables a company to use existing assets to

address problem areas. But a company usually has to

integrate slowly. First comes the soft integration

An Expert in a middling industry faces a different

set of options and choices. Like Amazon, it needs

to develop and defend proprietary barriers, empha-

sizing long-term market share over short-term

prots. It can build and exploit scale advantages,

perhaps pursuing preemptive acquisitions. It should

try to amaze its regular customersand it should

challenge itself by targeting those who are most

valuable and hard to please. As for competitors, the

best strategy is often to keep them guessing. Who

can forget Jeff Bezoss promise in late 2013 that Ama-

zon would someday deliver its products with drones?

Knowing your industrys rate of evolution and your

companys stage of development will also help you

navigate some of the central challenges that face any

organization as it confronts the Digical future.

Fast vs. slow. One of these challenges is the perennial

question of how fast to move. Going too slow and going

too fast are equally dangerous. Searss huge investment

in Prodigy was premature. So was the acquisition of

Fingerhut by Macys. Companies that move quickly

and jump out ahead of the others may not leave adequate

time for testing and learning. They may spend too heavily

in areas that dont materially increase sales and prot-

ability; they may hurt their profit margins and thus

their return on capital. If they miss their targets, they

may erode investors condence in the business and

its managers. Few people now remember Amazons

precarious situation in 2001, when its stock price had

plunged from $107 to $7. Were it not for a new CFO,

who raised $672 million in convertible bonds overseas

just a month before the stock market crashed, Amazon

would likely have faced insolvency.

Yet waiting for others to break expensive new ground

holds equal dangers. Companies can lose leadership

and scale. Regaining market share usually costs more

than holding onto it. Slow movers lose talented people,

and they risk sacrificing much of their equity with

customers, particularly with the younger buyers who

12

Leading a Digical

SM

transformation

solar panels on the roof and so on. Airlines are getting

their toes wet as well. Delta, for example, offers a baggage

tracker via Wi-Fi. It has equipped ight attendants with

handheld devices, and it is in the process of equipping

pilots with Surface 2 tablets as electronic ight bags

to take the place of papers and charts in the cockpit.

Delta also spent in the neighborhood of $140 million

to improve its website and mobile presence, leading

to a new iPad app that works as a travel guide. Among

the apps features is Glass Bottom Jet, which allows

passengers in flight to see the city below them on

their devices screen.

Even the US Postal Service is getting into the act. Though

email has decimated first-class letters, e-commerce

has led to a boom in package delivery, and private car-

riers lack capacity during peak periods. The USPS has

developed its tracking and logistical capabilities to the

point where it could partner with Amazon in the 2013

holiday season to facilitate Sunday deliveries.

Bottom line: It isnt too late. Companies everywhere

are experimenting and innovating, but most are still

Beginners. The Digical transformation is under way,

but it is still young. A company that climbs on board

now will have the strategies and the assets it needs to

compete in a Digical future.

socializing, bringing executive teams together, appre-

ciating what the other group can do. Then come the

harder steps, with dotted-line accountabilities link-

ing people in both units. Over timeonce people are

comfortable with one another and their respective

rolesthose lines can get stronger.

Looking ahead

The pace of change has been so rapid in recent decades

that many executives already feel left behind. This is a

mistake. The Digical transformation, like the computer

revolution itself, is a long race, and we are scarcely past

the starting line. Look at e-commerce. The Web has been

available for commercial use for about 20 years. Many

companies have built huge organizations around their

e-commerce capabilities and do billions of dollars worth

of business. But e-commerce still accounts for less

than 10% of retail sales.

Look, too, at all the companies now testing the waters

of the Digical transformation. Not long ago the auto-

mobile industry appeared to be stodgy and unimagi-

native, the quintessential old-economy business. Today,

companies such as Ford and Audi are developing sev-

eral Digical technologies: self-parking cars, wireless

networks linking cars to one another, electric cars with

Digical

SM

is a trademark of Bain & Company, Inc.

Shared Ambiion, Tru Rsults

Bain & Company is the management consulting rm that the worlds business leaders come

to when they want results.

Bain advises clients on strategy, operations, technology, organization, private equity and mergers and acquisitions.

We develop practical, customized insights that clients act on and transfer skills that make change stick. Founded

in 1973, Bain has 50 ofces in 32 countries, and our deep expertise and client roster cross every industry and

economic sector. Our clients have outperformed the stock market 4 to 1.

What sets us apart

We believe a consulting rm should be more than an adviser. So we put ourselves in our clients shoes, selling

outcomes, not projects. We align our incentives with our clients by linking our fees to their results and collaborate

to unlock the full potential of their business. Our Results Delivery

process builds our clients capabilities, and

our True North values mean we do the right thing for our clients, people and communitiesalways.

For more information, visit www.bain.com

Key contacts:

Americas: Mike Baxter in New York (mike.baxter@bain.com)

Darrell Rigby in Boston (darrell.rigby@bain.com)

Elizabeth Spaulding in San Francisco (elizabeth.spaulding@bain.com)

Suzanne Tager in New York (suzanne.tager@bain.com)

Asia-Pacic: Serge Hoffmann in Hong Kong (serge.hoffmann@bain.com)

Michael Woodbury in Melbourne (michael.woodbury@bain.com)

EMEA: Nick Greenspan in London (nick.greenspan@bain.com)

Marc-Andr Kamel in Paris (marc-andre.kamel@bain.com)

Dirk Vater in Frankfurt (dirk.vater@bain.com)

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Bain Case 1Documento11 pagineBain Case 1Ping Yuen SoNessuna valutazione finora

- MCG Casebook 2015 Edition Guide to Consulting InterviewsDocumento30 pagineMCG Casebook 2015 Edition Guide to Consulting InterviewsNaura TsabitaNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Interview Workshop Dartmouth College October 8, 2004Documento14 pagineCase Interview Workshop Dartmouth College October 8, 2004JamesNessuna valutazione finora

- Michigan Casebook 2005Documento116 pagineMichigan Casebook 2005Bob JohnsonNessuna valutazione finora

- Parthenon Mock CaseDocumento16 pagineParthenon Mock Casekr.manid@gmail.comNessuna valutazione finora

- EYP Practice Case - Protein BarDocumento15 pagineEYP Practice Case - Protein BarJohn ChaoNessuna valutazione finora

- BPR BainDocumento7 pagineBPR BainIshan KansalNessuna valutazione finora

- BCG Case ChinaDocumento25 pagineBCG Case ChinaJadeNessuna valutazione finora

- Bain IAB Digital Pricing ResearchDocumento23 pagineBain IAB Digital Pricing Researchandrew_null100% (5)

- Stepping Into 2021 - Chinese Consumer in The New Reality 20210301 - ENDocumento31 pagineStepping Into 2021 - Chinese Consumer in The New Reality 20210301 - ENwang raymondNessuna valutazione finora

- Presentation For UCLDocumento33 paginePresentation For UCLabrahamaudu100% (1)

- 2010-2011 Duke Fuqua MCC Case BookDocumento146 pagine2010-2011 Duke Fuqua MCC Case Bookr_okoNessuna valutazione finora

- BCG Round 1 Amazonian Dinosaur 3 1Documento19 pagineBCG Round 1 Amazonian Dinosaur 3 1John ChaoNessuna valutazione finora

- On-Line Case: Example For DistributionDocumento7 pagineOn-Line Case: Example For DistributionDamien ForestNessuna valutazione finora

- Chicken Pox Vaccine: 1 Round InterviewDocumento19 pagineChicken Pox Vaccine: 1 Round InterviewAnkur shahNessuna valutazione finora

- Real Cases 2021-329-348Documento20 pagineReal Cases 2021-329-348mariishaNessuna valutazione finora

- B C C (I) P T: S, K M P: AIN Apability Enter Ndia Osition Itle Pecialist Nowledge Anagement RogramDocumento2 pagineB C C (I) P T: S, K M P: AIN Apability Enter Ndia Osition Itle Pecialist Nowledge Anagement RogramManas SrivastavaNessuna valutazione finora

- Content: 1. Case IntroductionDocumento8 pagineContent: 1. Case IntroductionTeddy JainNessuna valutazione finora

- Bain & Company: Jump ToDocumento12 pagineBain & Company: Jump TonodisclosureNessuna valutazione finora

- 003 FiveLadies McKinseyDocumento15 pagine003 FiveLadies McKinseyWTNessuna valutazione finora

- Children Vaccine - Consulting CaseDocumento7 pagineChildren Vaccine - Consulting CaseJatin MehtaNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Ace The Case InterviewDocumento6 pagineHow To Ace The Case InterviewalejandroNessuna valutazione finora

- Holidays List 2019Documento8 pagineHolidays List 2019SR RaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Bain ThanksgivingDocumento12 pagineBain Thanksgivingjgravis100% (1)

- Tips PHD BCG PDFDocumento15 pagineTips PHD BCG PDFargha48126Nessuna valutazione finora

- ECO222 Lect Week9 2020 UDocumento39 pagineECO222 Lect Week9 2020 UKarina SNessuna valutazione finora

- Consulting Bootcamp - The Book Rev 06Documento34 pagineConsulting Bootcamp - The Book Rev 06Will BachmanNessuna valutazione finora

- 2018-19 BCC Career Pack VFDocumento11 pagine2018-19 BCC Career Pack VFSuyash AgrawalNessuna valutazione finora

- Chicago GSB Casebook 2007Documento143 pagineChicago GSB Casebook 2007Archibald_Moore100% (1)

- BAIN BRIEF - Decision Insights - How Group Dynamics Affect DecisionsDocumento4 pagineBAIN BRIEF - Decision Insights - How Group Dynamics Affect Decisionsapritul3539Nessuna valutazione finora

- Case Book 1 2016 82613245 82613245Documento60 pagineCase Book 1 2016 82613245 82613245m n gNessuna valutazione finora

- Presentation 2Documento19 paginePresentation 2Dimas Haryo Adi PrakosoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Pricing Game (Stern 2018)Documento10 pagineThe Pricing Game (Stern 2018)a ngaiNessuna valutazione finora

- Mckinsey Case2002Documento19 pagineMckinsey Case20021pisco1100% (2)

- CBS Case Club - Case Interview HandbookDocumento44 pagineCBS Case Club - Case Interview HandbookducminhlnilesNessuna valutazione finora

- I Want To Work in Management ConsultingDocumento2 pagineI Want To Work in Management ConsultingSelin TarhanNessuna valutazione finora

- 10 Consulting Frameworks To Learn For Case Interview - MConsultingPrepDocumento25 pagine10 Consulting Frameworks To Learn For Case Interview - MConsultingPrepTushar KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Simulado BainDocumento10 pagineSimulado BainVictor Nassau BatistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Preparing For Your Interviews With Mckinsey: ConfidentialDocumento34 paginePreparing For Your Interviews With Mckinsey: Confidentialarif420_999Nessuna valutazione finora

- Bain StoriesDocumento44 pagineBain Storiesmichaelburke47100% (1)

- Bain Interactive Interview Blank SlidesDocumento7 pagineBain Interactive Interview Blank SlidesDavid MiguelNessuna valutazione finora

- Mckinsey PrepDocumento1 paginaMckinsey PrepEisha AbidNessuna valutazione finora

- Harvard HBS Casebook 2011Documento139 pagineHarvard HBS Casebook 2011CarolineNessuna valutazione finora

- Parrot Analytics - The Global TV Demand Report Q2 2018Documento55 pagineParrot Analytics - The Global TV Demand Report Q2 2018Federico GonzalezNessuna valutazione finora

- Consultant's Love LifeDocumento11 pagineConsultant's Love LifeBenjamin Tseng100% (3)

- IIM Shillong Student Seeks Summer Internship at BCN GurugramDocumento1 paginaIIM Shillong Student Seeks Summer Internship at BCN GurugramKshitij JainNessuna valutazione finora

- Understand Market Size, Revenue Sources, and Cost DriversDocumento10 pagineUnderstand Market Size, Revenue Sources, and Cost DriversAnurag KhaireNessuna valutazione finora

- BCG CaseInterviewGuide PDFDocumento33 pagineBCG CaseInterviewGuide PDFalexandre1411Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cupid Arrow PDFDocumento10 pagineCupid Arrow PDFWill LumNessuna valutazione finora

- Romance: A BCG Analysis: Original by Andy Meyer June, 1996Documento11 pagineRomance: A BCG Analysis: Original by Andy Meyer June, 1996GovindrakeshNessuna valutazione finora

- Tuck Casebook 2008 DraftDocumento115 pagineTuck Casebook 2008 Draftpawankolhe100% (1)

- Certified Management Consultant A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionDa EverandCertified Management Consultant A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionNessuna valutazione finora

- Energy Consulting A Complete Guide - 2021 EditionDa EverandEnergy Consulting A Complete Guide - 2021 EditionNessuna valutazione finora

- Management Consulting A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionDa EverandManagement Consulting A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionNessuna valutazione finora

- Leading A Digical TransformationDocumento14 pagineLeading A Digical Transformationshabir khanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Swipe-Right Customer Experience: How to Attract, Engage, and Keep Customers in the Digital-First WorldDa EverandThe Swipe-Right Customer Experience: How to Attract, Engage, and Keep Customers in the Digital-First WorldNessuna valutazione finora

- Human Capital in The Digital EconomyDocumento6 pagineHuman Capital in The Digital EconomyalphathesisNessuna valutazione finora

- Transformational Products: The code behind digital products that are shaping our lives and revolutionizing our economiesDa EverandTransformational Products: The code behind digital products that are shaping our lives and revolutionizing our economiesNessuna valutazione finora

- TRIVERGENCE: Accelerating Innovation with AI, Blockchain, and the Internet of ThingsDa EverandTRIVERGENCE: Accelerating Innovation with AI, Blockchain, and the Internet of ThingsNessuna valutazione finora

- Digital Transformation IBMDocumento20 pagineDigital Transformation IBMNina RungNessuna valutazione finora

- The Phygital Bank PDFDocumento14 pagineThe Phygital Bank PDFbilloukosNessuna valutazione finora

- OpineBox Business ModelDocumento22 pagineOpineBox Business ModelbilloukosNessuna valutazione finora

- The Phygital Banking Transformation PDFDocumento14 pagineThe Phygital Banking Transformation PDFbilloukos100% (2)

- The Phygital Bank PDFDocumento14 pagineThe Phygital Bank PDFbilloukosNessuna valutazione finora

- Bit Publication East Fa WebDocumento53 pagineBit Publication East Fa WebbilloukosNessuna valutazione finora

- Media Bias and ReputationDocumento37 pagineMedia Bias and ReputationbilloukosNessuna valutazione finora

- II. International Conference On Communication, Media, Technology and DesignDocumento6 pagineII. International Conference On Communication, Media, Technology and DesignbilloukosNessuna valutazione finora

- Valuing New Goods in A Model With Complementarity: Online NewspapersDocumento32 pagineValuing New Goods in A Model With Complementarity: Online NewspapersbilloukosNessuna valutazione finora

- Ideological Segregation Online and OfflineDocumento46 pagineIdeological Segregation Online and OfflinebilloukosNessuna valutazione finora

- Vasileios Tziokas Sample Portfolio July 2014Documento73 pagineVasileios Tziokas Sample Portfolio July 2014billoukosNessuna valutazione finora

- Red BullDocumento8 pagineRed BullbilloukosNessuna valutazione finora

- The Price of Attention Online and OfflineDocumento13 pagineThe Price of Attention Online and OfflinebilloukosNessuna valutazione finora

- The Most Contagious Ideas of The Year 2013Documento96 pagineThe Most Contagious Ideas of The Year 2013Boris LoukanovNessuna valutazione finora

- Story PostAD SurvivalGuide NudgeMktingDocumento16 pagineStory PostAD SurvivalGuide NudgeMktingbilloukosNessuna valutazione finora

- Uk Future of Out of Home ReportDocumento28 pagineUk Future of Out of Home ReportbilloukosNessuna valutazione finora

- Disruptive Technologies McKinsey May 2013Documento176 pagineDisruptive Technologies McKinsey May 2013mattb411Nessuna valutazione finora

- In The Creative Economy There Is No Such Thing As Free'. DiscussDocumento12 pagineIn The Creative Economy There Is No Such Thing As Free'. DiscussbilloukosNessuna valutazione finora

- Research 2012 DA AttitudesDocumento1 paginaResearch 2012 DA AttitudesbilloukosNessuna valutazione finora

- Research 2012 DA AttitudesDocumento1 paginaResearch 2012 DA AttitudesbilloukosNessuna valutazione finora

- NIELSEN - Global Trust in Advertising 2012Documento10 pagineNIELSEN - Global Trust in Advertising 2012Stefano CeresaNessuna valutazione finora

- IAB Internet Advertising Revenue Report FY 2011Documento29 pagineIAB Internet Advertising Revenue Report FY 2011billoukosNessuna valutazione finora

- The: A Wearable Device For Understanding Human Networks: SociometerDocumento28 pagineThe: A Wearable Device For Understanding Human Networks: SociometerbilloukosNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is FreemiumDocumento8 pagineWhat Is FreemiumbilloukosNessuna valutazione finora

- Game TheoryDocumento52 pagineGame TheoryMohit SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ip EssayDocumento14 pagineIp EssaybilloukosNessuna valutazione finora

- First Time Login Guidelines in CRMDocumento23 pagineFirst Time Login Guidelines in CRMSumeet KotakNessuna valutazione finora

- Platform Tests Forj Udging Quality of MilkDocumento10 paginePlatform Tests Forj Udging Quality of MilkAbubaker IbrahimNessuna valutazione finora

- Ten Lessons (Not?) Learnt: Asset AllocationDocumento30 pagineTen Lessons (Not?) Learnt: Asset AllocationkollingmNessuna valutazione finora

- Vipinesh M K: Career ObjectiveDocumento4 pagineVipinesh M K: Career ObjectiveJoseph AugustineNessuna valutazione finora

- FIITJEE Talent Reward Exam 2020: Proctored Online Test - Guidelines For StudentsDocumento3 pagineFIITJEE Talent Reward Exam 2020: Proctored Online Test - Guidelines For StudentsShivesh PANDEYNessuna valutazione finora

- Negotiating For SuccessDocumento11 pagineNegotiating For SuccessRoqaia AlwanNessuna valutazione finora

- Puberty and The Tanner StagesDocumento2 paginePuberty and The Tanner StagesPramedicaPerdanaPutraNessuna valutazione finora

- Treviranus ThesisDocumento292 pagineTreviranus ThesisClaudio BritoNessuna valutazione finora

- Gambaran Kebersihan Mulut Dan Karies Gigi Pada Vegetarian Lacto-Ovo Di Jurusan Keperawatan Universitas Klabat AirmadidiDocumento6 pagineGambaran Kebersihan Mulut Dan Karies Gigi Pada Vegetarian Lacto-Ovo Di Jurusan Keperawatan Universitas Klabat AirmadidiPRADNJA SURYA PARAMITHANessuna valutazione finora

- SCIENCE 5 PPT Q3 W6 - Parts of An Electric CircuitDocumento24 pagineSCIENCE 5 PPT Q3 W6 - Parts of An Electric CircuitDexter Sagarino100% (1)

- Kristine Karen DavilaDocumento3 pagineKristine Karen DavilaMark anthony GironellaNessuna valutazione finora

- It ThesisDocumento59 pagineIt Thesisroneldayo62100% (2)

- Simply Learn Hebrew! How To Lea - Gary Thaller PDFDocumento472 pagineSimply Learn Hebrew! How To Lea - Gary Thaller PDFsuper_gir95% (22)

- Structuring Your Novel Workbook: Hands-On Help For Building Strong and Successful StoriesDocumento16 pagineStructuring Your Novel Workbook: Hands-On Help For Building Strong and Successful StoriesK.M. Weiland82% (11)

- SyllabusDocumento8 pagineSyllabusrickyangnwNessuna valutazione finora

- Pervertible Practices: Playing Anthropology in BDSM - Claire DalmynDocumento5 paginePervertible Practices: Playing Anthropology in BDSM - Claire Dalmynyorku_anthro_confNessuna valutazione finora

- Summer 2011 Redwood Coast Land Conservancy NewsletterDocumento6 pagineSummer 2011 Redwood Coast Land Conservancy NewsletterRedwood Coast Land ConservancyNessuna valutazione finora

- Group Assignment Topics - BEO6500 Economics For ManagementDocumento3 pagineGroup Assignment Topics - BEO6500 Economics For ManagementnoylupNessuna valutazione finora

- Study Habits Guide for Busy StudentsDocumento18 pagineStudy Habits Guide for Busy StudentsJoel Alejandro Castro CasaresNessuna valutazione finora

- Written Test Unit 7 & 8 - Set ADocumento4 pagineWritten Test Unit 7 & 8 - Set ALaura FarinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Pembaruan Hukum Melalui Lembaga PraperadilanDocumento20 paginePembaruan Hukum Melalui Lembaga PraperadilanBebekliarNessuna valutazione finora

- 1803 Hector Berlioz - Compositions - AllMusicDocumento6 pagine1803 Hector Berlioz - Compositions - AllMusicYannisVarthisNessuna valutazione finora

- Cover Letter IkhwanDocumento2 pagineCover Letter IkhwanIkhwan MazlanNessuna valutazione finora

- MES - Project Orientation For Night Study - V4Documento41 pagineMES - Project Orientation For Night Study - V4Andi YusmarNessuna valutazione finora

- Simptww S-1105Documento3 pagineSimptww S-1105Vijay RajaindranNessuna valutazione finora

- Final DSL Under Wire - FinalDocumento44 pagineFinal DSL Under Wire - Finalelect trsNessuna valutazione finora

- Global Supplier Quality Manual SummaryDocumento23 pagineGlobal Supplier Quality Manual SummarydywonNessuna valutazione finora

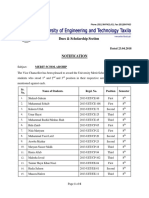

- Dues & Scholarship Section: NotificationDocumento6 pagineDues & Scholarship Section: NotificationMUNEEB WAHEEDNessuna valutazione finora

- Factors Affecting Job Satisfaction of EngineersDocumento35 pagineFactors Affecting Job Satisfaction of Engineerslingg8850% (2)

- Forouzan MCQ in Error Detection and CorrectionDocumento14 pagineForouzan MCQ in Error Detection and CorrectionFroyd WessNessuna valutazione finora