Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Cambridge University Press Digitizes Early Music History Journal

Caricato da

Marcel Camprubí PeiróDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Cambridge University Press Digitizes Early Music History Journal

Caricato da

Marcel Camprubí PeiróCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Early Music History.

http://www.jstor.org

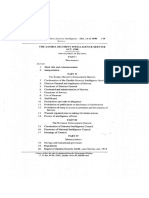

Music, Identity and the Inquisition in Fifteenth-Century Spain

Author(s): Eleazar Gutwirth

Source: Early Music History, Vol. 17 (1998), pp. 161-181

Published by: Cambridge University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/853882

Accessed: 10-08-2014 15:06 UTC

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content

in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship.

For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

This content downloaded from 84.88.64.86 on Sun, 10 Aug 2014 15:06:46 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Early

Music

History

(1998)

Volume 17.

?

1998

Cambridge University

Press

Printed in the United

Kingdom

ELEAZAR GUTWIRTH

MUSIC,

IDENTITY AND THE

INQUISITION

IN

FIFTEENTH-CENTURY SPAIN*

'Citola,

odrecillo non amar

cagmil

hallaco.'

(The

citola and the

bagpipes

do not suit an Arab

man)'

Sometime between the

years

1330 and

1343,Juan

Ruiz,

Archpriest

of Hita in

Castile,

included this maxim in his

literary masterpiece,

the Libro de buen amor. This

verse,

like others in the

poem,

attrib-

utes an ethnic

identity

both to

objects

and to vocal

music,

a form

of ethnic

marking

that has been

preserved

in

Spanish

culture

by

linguistic usage:

the Arabic

particle a[1]

in the

prefix

to words for

musical instruments such as

adufe (square tambourine), ajabeba

(transverse flute)

or

anafil (a straight trumpet

four feet or more

in

length)

is a

possible

reminder of this

phenomenon.2

About a

century

later,

the chronicler Alonso de Palencia

(d. 1492) applied

similar ethnic

markings

when

speaking

of the music of a

young

Castilian converso who was to become one of the most

powerful

courtiers of

King Enrique

IV,

Diego

Arias

Daivila:

'per

rura

sego-

biensia...

cantibusque

arabicis advocabat sibi coetu rusticorum'.3

When,

some

forty years ago,

Menendez Pidal

attempted

to

reconstruct the historical context of the Libro de buen amor

(includ-

ing

its verses on music and musical

instruments)

in a

way

that

would both

explain

its historical

background

and confirm its his-

torical

validity

and

accuracy,

he considered the

particular

case of

* This article is a revised version of a

paper presented

to the

Hispanic

Cultures Research

Group

directed

by

Dr

Inger

Enkvist at the Romanska Institution of the

University

of

Lund, Sweden,

in

September

1996.

I

should like to

express my gratitude

to Dr Enkvist

and all the other

participants

for their comments and

encouragement.

Libro de buen amor. The Book

of

True

Love,

trans. S. R.

Daly,

ed. A. N. Zahareas

(Philadelphia,

1973),

lines 1516-17.

2 R.

Stevenson, Spanish

Music in the

Age of

Columbus

(The Hague, 1960), pp.

22-3.

3 Palencia,

Cr6nica de

Enrique IV,

ed. A. Paz

y

Melia

(Madrid, 1973),

D6cada I

(lib. iii, cap.

5),

and Men6ndez Pidal

(see

note

4).

161

This content downloaded from 84.88.64.86 on Sun, 10 Aug 2014 15:06:46 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Eleazar Gutwirth

this

fifteenth-century Jewish

converso.4

There is some

significance

in the fact

that,

on the one

hand,

the

fourteenth-century

Christian

Castilian

masterpiece appears

to show such

familiarity

with Arabic

music and

that,

on the

other,

Men6ndez

Pidal should have

used,

as historical embodiment of the

poet's

views,

the case of a musi-

cian of

Jewish

birth and cultural

background

who became a

courtier. Of

course,

the texts used

by

Men6ndez

Pidal now

appear

to be far more

problematic

and

ambiguous

than

they

did at the

time5 (he claimed,

for

example,

that in the

songs

of the

Sephardi

women of North

Africa,

as

sung

in the

early

twentieth

century,

could be heard 'the sounds of the Castile of the Catholic

Monarchs').' Nevertheless,

his

emphasis

on the

significance

of

fifteenth-century Hispano-Jewish

musical

practice

has now become

an

accepted part

of

scholarly

concern. Whether or not

they accept

the

fifteenth-century dating

for the

origin

of the musical traditions

that have been collected and studied

only

in the nineteenth and

twentieth

centuries,

historians of music have

repeatedly

returned,

for more than a

century,

to the

problem

of the musical

practices

of

fifteenth-century hispanic Jewry,

that is to

say

to the music

which the

Jews

exiled from

Spain

in 1492

may

have taken with

them to their various

destinations.7 Paradoxically, despite

the rich-

4

R. Menandez

Pidal, Poesiajuglarescayjuglares (Madrid, 1957), p.

229.

5

On

the Latin and French sources or

analogues

of some of the references to musical

instruments in the Libro de buen

amor,

see F.

Lecoy,

Recherches sur le Libro de buen

amor,

ed.

A. D.

Deyermond (Farnborough, 1974), p. 260,

who discusses the list of instruments

which

greet

Love and its

dependence

on

previous

models even in

apparently

local details

such as Moorish instruments. See also D.

Devoto,

'La

enumeraci6n

de instrumentos

musicales en la

poesia

medieval castellana' in

Misceldnea

en

Homenage

a

H.

Anglis

(Barcelona, 1958-61), pp.

211-22.

Similarly problematic

is the other

source, though

for

different reasons. The

problems

of

using

Palencia's chronicle for

anyone

connected with

Enrique

IV

are well

known,

and in the case of

Diego

Arias

they may

be

compounded by

his

Jewish origins.

On the

problem

of the

representation

of

Jews

and

judaisers

in

Castilian chronicles of the

period,

see E.

Gutwirth,

'The

Jews

in

15th-Century

Castilian

Chronicles',Jewish Quarterly Review, 84,

no. 4

(1984), pp.

379-96. There is little evidence

to show that Palencia knew either Arabic or

Hebrew,

or that he could

distinguish

between

these

differing

musical traditions.

6

R. Menendez

Pidal,

Poesia

populary poesia

tradicional en

la

literatura

espahiola.

Conferencia

leida

en All Souls'

College 26/6/1922 (Oxford, 1922).

7

See for

example

E. Gerson

Kiwi,

'On the Musical Sources of the

Judeo-Spanish

Romance',

Musical

Quarterly,

50

(1964), pp. 31-43;

H.

Avenary,

'Old Melodies to

Sephardic

pizmonim' (in Hebrew),

in Tesoro de

losjudios sefardies,

3

(1960), pp. 149-53; idem,

'Cantos

espafioles

antiguos

mencionados en la literatura

hebrea',

Anuario

Musical,

25

(1971), pp.

67-79; J.

Etzion and S.

Weich-Shahak,

'The

Spanish

and the

Sephardic

Romances:

Musical

Links', Ethnomusicology,

32

(1988), pp. 1-37; idem,

'The

Spanish

"Romances

viejos"

and the

Sephardic

Romances: Musical Links across Five

Centuries',

Atti del XVI

Congreso

della Societac Internazionale

di

Musicologia (1989), pp.

7-16.

162

This content downloaded from 84.88.64.86 on Sun, 10 Aug 2014 15:06:46 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Music, Identity

and the

Inquisition

in

Fifteenth-Century Spain

ness of the

repertory,

and the evident

importance

and the

frequent

use made of the

songs

that have been collected in our own cen-

tury (in disciplines

such as the

literary history

of

fifteenth-century

Spain),

the

fifteenth-century

sources mentioned in the

scholarly

literature on the

subject

are both scant and

problematic.

A recent

study

has

gone

so far as to affirm that

'existing

data

concerning

the music of the

Jews

in

Spain prior

to the

expulsion

is almost

nil'.8

The

question

would

appear

to be

why

such a rich tradition

seems to have left so

very

few traces in the

pre-expulsion

evidence.

It is

against

this

background

of the

paucity

of sources mentioned

in the

scholarly

literature and their

problematic

nature that it

may

be

suggested

that there

does,

in

fact,

exist a

type

of fifteenth-

century

evidence

which,

though neglected, may

nevertheless be

used to reconstruct some

aspects

of

Hispano-Jewish

musical

prac-

tice and their

meaning: namely,

the records of the

Spanish

Inquisition.

Here attention

may

be focused on

Diego

Arias

Daivila

himself,

because of the

importance

attributed to his music

by

his

contemporaries (Palencia

is

only

one of

them)

and

by

later his-

torians

(such

as

Men6ndez

Pidal)

on the one

hand,

and because

of the relative wealth of material

provided by

the

Inquisition

records themselves on the other.

Diego

Arias

(d. 1466)

was a civil servant of some social and

polit-

ical

importance, being,

at various

times,

contador

mayor (an

office

akin to chief treasurer of the

kingdom

of

Castile), secretary

to the

king,

chief

notary

of the

king's privileges throughout

his

royal

and

seigneurial

lands,

notary public

in the

king's

court,

and a member

of the

royal

council. His name

appears

in the

marriage

contract

drawn

up

in 1455 between

Enrique

IV and

Juana,

the sister of the

King

of

Portugal,

thus

showing

his active involvement in the

dynas-

tic affairs of the crown. Arias was also

part

of the alliance between

Enrique

IV and the most

powerful

men of the realm: Alfonso de

Fonseca,

Archbishop

of

Seville;

Don Pedro

Gir6n,

Master of

Calatrava;

Alvaro de

Est(iniga,

Count of

Plasencia;

Juan Pacheco,

Marquess

of

Villena;

and Alfonso

Pimentel,

Count of Benavente.

He was in turn the founder of a

dynasty

which included the

Bishop

of

Segovia;

a

prothonotary

of the

kingdom;

an

early conquistador

8 See E.

Seroussi,

'Between Eastern and Western Mediterranean:

Sephardic

Music after

the

Expulsion

from

Spain

and

Portugal',

Mediterranean Historical

Review,

6

(1991), pp.

198-206.

163

This content downloaded from 84.88.64.86 on Sun, 10 Aug 2014 15:06:46 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Eleazar Gutwirth

who founded Panama and was the first

governor

of

Nicaragua;

and

the counts of

Pufionostro.9

For

us,

it is his cultural and artistic

activities that are of

greater

interest. His

opulent

mansion in

Segovia

excited the

envy

even of noble families such as the

Mendozas because of features of its

design

and

furnishings

such

as the

golden ceilings,

the

cups

and vases encrusted with

precious

jewels,

and the bedsheets of fine holland linen. Ostentation on this

scale

naturally

evoked

comparisons

with the

magnificence

of

emperors, popes

and

cardinals,

and the

reports

of

contemporaries

mention the numerous seekers for his favour who would wait on

him laden with

presents.

It is

probable

that Arias was a

patron

of

poets

and of the

manuscript

illuminators and

painters

who

stayed

in his house. His wife's

reading

habits were considered remark-

able

by

her

Segovian neighbours,

who recalled in detail the

splen-

did

bindings

of her books. His

son,

the

bishop

of

Segovia,

and his

book-collecting

activities are

famous

and are a source of

pride

to

Segovians

to this

day.

The

bishop

has been credited with the

early

introduction of features of Renaissance architecture into

Spain,

particularly

in the

design

of the

bishop's palace

at

Tur6gano.'o

From the

fifteenth-century Inquisition

evidence on

Arias

one

may

reconstruct

aspects

of musical

practice

which are

usually ignored:

information about

repertory,

the

places

in which musical

perfor-

mance took

place,

the nature of the audience and its critical

responses,

and,

most

importantly

for us

here,

the

significance

of

this music in its social and historical context.

9

On the conversos in

fifteenth-century

Castile in

general,

see Y.

Baer,

A

History of

the

Jews

in Christian

Spain,

vol.

II (Philadelphia, 1978).

On

Diego

Arias's

Inquisition

file and its

historical

interpretation,

see E.

Gutwirth, 'Jewish-Converso

Relations in XVth c.

Segovia', Proceedings of

the

Eighth

World

Congress

ofJewish

Studies,

B

(Jerusalem, 1982), pp.

49-53; idem,

'Elementos

6tnicos

e hist6ricos en las relaciones

judeo-conversas

en

Segovia',

Jews

and

Conversos,

ed. Y.

Kaplan (Jerusalem, 1985), pp.

83-102; idem,

'On the

Background

to Cota's

Epitalamio

Burlesco',

Romanische

Forschungen,

97,

1

(1985), pp.

1-14; idem,

'Abraham Seneor: Social Tensions and the

Court-Jew', Michael,

11

(1999), pp.

169-229;

idem,

'From

Jewish

to Converso Humour in Fifteenth

Century Spain',

Bulletin

ofHispanic

Studies,

67

(1990), pp.

223-33. All references are to the excellent

transcriptions by

C.

Carrete Parrondo in Fontes

Iudaeorum Regni

Castellae,

vol.

III

(Salamanca, 1986),

hereafter

cited as 'FIRC'.

10

On

Diego

Arias see the notes to the studies of his

Inquisition

file mentioned

above;

also

J. Rodriguez

Pu6rtolas,

Poesia

criticay

satirica del

siglo

xv

(Madrid, 1984), andJ.

M.

Azceta,

El Cancionero dejuan Ferndndez

de Ixar

(Madrid, 1956) pp.

447ff.

164

This content downloaded from 84.88.64.86 on Sun, 10 Aug 2014 15:06:46 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Music,

Identity

and the

Inquisition

in

Fifteenth-Century Spain

THE SPACES OF

JEWISH

MUSIC

The

Inquisitors'

records

relating

to the Arias D

ivila

family

show

the extent to which his

contemporaries

felt the

places

where his

music was

performed

to be

important.

A number of

descriptions

of his

singing

have been

preserved

in these

documents,

and of

course there

may

have been other

depositions given

before the

Inquisition

tribunal which have not survived. The file itself

repre-

sents

only

a selection from the books of the

Segovian

and other

Inquisition tribunals,

and the

depositions

were

given

at least

twenty years

after the events which

they

describe. This is in itself

an

eloquent testimony

to the memorable nature of his

perfor-

mances.

Moreover,

some of these accounts were

given

at second

hand

by

witnesses who remembered

hearing

about his

perfor-

mances but had not

experienced

them

personally; evidently they

were also the

subject

of

private

conversations

amongst Diego

Arias's

contemporaries. Specifications

of the

place

of

performance,

usually

included in these

accounts,

differ somewhat from the

better-documented ones of Christian secular music or

Jewish

and

Christian

liturgical

music in

fifteenth-century Spain:

the

syna-

gogue,

the

church,

the

private chapel

and the streets

during pro-

cessions." In

May 1489,

Rabbi

Simoel,

doctor to the Duke of

Albuquerque,

testified under oath that he had heard maestre

Josep,

his

father,

speak

about

Diego

Arias's

music,

and that it had

been

performed

'while

walking

one

day

...

[and] they

were left

alone

separated

from the other

people

who were with them'.'2

In

April 1486,

Rabbi David Gome testified that he had heard one

Jacob

talk about

Diego

Arias's

singing;

this time the

performance

11

For the

places

where music was

performed

in

fifteenth-century Spain

and their

analy-

sis,

see

e.g.

K.

Kreitner,

'Music in the

Corpus

Christi Procession of

Fifteenth-Century

Barcelona', Early

Music

History,

14

(1995), pp. 153-204;

see also T.

Knighton,

'Ritual and

Regulations:

The

Organization

of the Castilian

Royal Chapel during

the

Reign

of the

Catholic

Monarchs',

Misceldnea ...

Jose Ldpez-Calo

S.

J.,

coord. E. Casares and C.

Villanueva,

vol. I

(Santiago

de

Compostela, 1990), pp. 291-320,

which

emphasises

that

the

royal chapel

was not so much a

space

as a

body

of

clergy.

There are

images

of

per-

formance

spaces in,

for

example,

the

breviary

illuminated in Flanders

during

the last

decade of the fifteenth

century

for

Queen

Isabella

(now London,

British

Library

Add.

MS

18851)

on fol.

164,

where

King

David is shown surrounded

by

the

singers

of the 'old

song'

of the Old Testament. See

J. Backhouse,

The Isabella

Breviary

(London, 1993), pl.

24. For the

performance

of Christian secular music in

Spain

see also

M.

C.

G6mez

Muntane,

La muzsica en

la

casa real

catalano-aragonesa (1336-1442),

vol. I

(Barcelona, 1979).

12 FIRC No.

104, p.

62.

165

This content downloaded from 84.88.64.86 on Sun, 10 Aug 2014 15:06:46 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Eleazar Gutwirth

had taken

place

in an inn where

Diego

Arias had been

lodged

while

in Medina del

Campo,

in a room which had a table laid out with

tablecloth.'3 Jacob Castellano,

a

Jewish

vecino of Medina del

Campo, referring

to the

event,

recalled that 'it

happened twenty-

six

years ago [that

is to

say,

around

1460],

when this witness was

about twelve

years

old ...

Diego

Arias came to the said

city

of

Medina

[del Campo];

he

lodged

in the house of Francisco Ruiz

and the late

G6mez

Gongilez

and don

Ynge [i.e. Yuge

=

Joseph]

Abeata and don

Qulema

... and while

being

there in the said

lodg-

ing

...

[in] Diego

Arias's

retraymiento

where he was with the said

Jews.'14

Rabbi Mosse aben

Mayor

testified that he had heard

[Ynge] Yuge

aben

Mayor

talk about

Diego

Arias's

singing

in

Villalpando,

where

Diego

Arias

lodged

in the house of the wit-

nesses' mother. 'Some

nights

after he came from the

palace [...]

after he had dined he would ask for the said

Yuge

to be sent to

him,

and he would

go

down to a

great

kitchen where he was and

he would order

everybody

out and would order the said

Yuge

to

shut the door and would tell him to

sing.'5

Later,

in

May

1487,

Don

Juda

(Qaragoza

testified how

Diego

Arias had

sung

to him 'one

day going

on the

way

to

Chinch6n'.'6

So

Diego

Arias

sang Jewish songs

on the

road,

in

Jewish

house-

holds,

in the

privacy

of his own

house,

in a kitchen and in his room

at an inn in Medina del

Campo.

These were not the

public spaces

implied by

Palencia's account

but,

on the

contrary, places

where

intimacy

and

privacy

were of the essence of the occasion. Alonso

Henriquez

testified in October of the same

year

that

Diego

Arias

had told him that 'if there was

anything

after this world for the

soul ... it was the voices of the

prayers

of the

Jews

which would

do for him because behind the said

monastery

of La Merced there

was a

synagogue'."7

The

places

where music was

performed

were

evidently present

in these

memories,

but

Diego's reported

com-

'3 FIRC No.

179, p.

102.

'4

FIRC No.

187, p.

106. On the

significance

of the

retraymiento,

see E.

Gutwirth,

'Habitat

and

Ideology:

The

Organization

of Private

Space

in Late

Medievaljuderias',

Mediterranean

Historical

Review,

9

(1994), pp.

205-34. For

yet

another

place

where music was

possibly

performed (it

was

certainly

a

place

for

prayer),

the huerta of

Diego

Arias near the

gate

of San

Martin,

see FIRC No. 82.

'5

FIRC No.

111, p.

203.

16 FIRC No.

219, p.

115.

'7

FIRC No.

66,

p.

43.

166

This content downloaded from 84.88.64.86 on Sun, 10 Aug 2014 15:06:46 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Music,

Identity

and the

Inquisition

in

Fifteenth-Century Spain

ment is an observation on the intersection between

space,

musi-

cal

meaning

and the conflict between Church and

Synagogue.

What Arias was

affirming,

in

fact,

was that near his tomb two kinds

of music would be voiced: the Christian music of the

monastery

of La Merced and the

Jewish

music of the

nearby synagogue.

Music

was not seen as divorced from the

spaces

of

religious identity.

The

idea has wider

implications,

some of which are

expressed

in liter-

ary

texts;

for

example,

a

poem by

Pero Ferrus in the Cancionero de

Baena is based

precisely

on the contrast between two musical tra-

ditions which

represent, metonymically,

the two

religions.

This

poem

also

appeals

to

stereotypes

of what was

thought

in medieval

Spain

to be a distinctive

'Jewish

voice'. What

may

need

emphasis

is that such

ideas,

despite

first

impressions,

were not mere liter-

ary topoi

that existed

exclusively

within the bounds of written

literary

texts,

but formed

part

of a wider

spectrum

of social men-

talities;

the archival records of the

Inquisition provide

us with

evidence of their oral

currency.18

AUDIENCE

We

may

also

partly

reconstruct the audience for

Diego

Arias's

singing

from the

Inquisition

records. Most of the witnesses who

testified to

Diego

Arias's

singing

were neither conversos nor

Christians,

but

Jews.

This has a certain

significance.

Previous

neglect

of this kind of archival material

may

have been based on

preconceptions

about its exclusive concern with conversos. But the

file,

it

may

be

argued,

has left evidence not

only

about the activ-

ities of the

Inquisition

and of the conversos but also about the men-

tality

of the

Jews and,

in

particular,

of a

relatively

well-defined

group

within

Jewish society

that

may

be

loosely

described as the

leaders of the

community

and their

associates,

people

who moved

within a concrete

geographic

area

(central Castile)

and who had

relations with

Segovia.

Abraham

Seneor,

for

example,

was a resi-

dent of

Segovia

and a chief tax collector as well as

being

Chief

Judge

and Chief Rabbi of the

Jews; Jacob

Castellano,

the

Jewish

18 This

topos

will be studied in detail elsewhere. Pero Ferrus's

Cantiga

has been

frequently

cited in the

literature; see,

for

example,

the Cancionero de Baena

(Leipzig, 1860), p.

319.

In the usual

interpretation,

the reverse of

my own,

it is seen as an

unproblematic

model

of 'convivencia'.

167

This content downloaded from 84.88.64.86 on Sun, 10 Aug 2014 15:06:46 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Eleazar Gutwirth

vecino of Medina del

Campo,

was an official of the

Jewish

commu-

nity;

Rabbi David Gome is described as someone who was resident

in Medina del

Campo;

Rabbi Samuel was the doctor of the Duke

of

Albuquerque,

while the

Segovian

Alonso

Henrfquez

was also a

Jew

in

Diego

Arias's lifetime.

They

were all

part

of

Diego

Arias's

circle,

that is to

say people

who were in contact with

well-placed

officials in

Enrique

IV's administration,

and as such can

hardly

be

described as a

popular

audience.

Nevertheless,

according

to one

testimony given

in

1486,

those 'who lived with

Diego

Arias' would

talk about his Hebrew

songs: 'que oyo

decir a muchos

que

vivian

con

Diego

Arias';

'people

who lived with him' is a

frequent phrase

in the romance literature of the

period

to describe 'his

servants',

i.e. the servants who lived in his house. This

reported

remark

may

be used to reconstruct

Diego

Arias's behaviour in the

privacy

of

his

home.'19

Some of the testimonies

given

before the

Inquisition

show that Arias's audience also included a number of conversos. On

19

April

1489 a

description

of one of his

performances

was

given

by

the uncle of Fernando

Albarez, who,

after

describing Diego

Arias's

singing,

added,

'y

estale escuchando e

oyendo

Alonso

Gon?alez

de la Oz e otros

biejos' ('and

Alonso

Gon?alez

de la Oz

was

listening

and

hearing

him,

with other old

men').20

These fam-

ilies

(de

la

Oz,

del

Rio, etc.)

also

belong

to a well-defined

group

within

Segovian society

in the second half of the fifteenth

century.

Their names

appear frequently

in

Segovian

business and admin-

istration

records;

they belonged

to the

city

council and were

part

of the

upper

echelons of the urban

oligarchy.

REPERTORY

The

Inquisition

records

repeatedly

refer to

specific

items of

music,

in contrast to other texts

(theoretical

texts in this or other

Inquisition

files with less detailed

testimonies)

where the music is

not described.

Nevertheless,

some of these testimonies refer to

Jewish songs

not

sung by Diego

Arias,

while others refer to

songs

19

On these

individuals,

see the studies mentioned in note 9 above. Other recorded lis-

teners are the

Jew

Abraham

Saragossi, Diego

Arias's

majordomo

in

Segovia;

Qulema

aben

Shushan,

a

Jewish

tax-collector;

and

Judah Saragossa,

a

Segovian Jewish

commu-

nity

official c. 1482. See FIRC

p. 74; p. 73; p. 115

and

p.

102.

20

FIRC No. 111.

168

This content downloaded from 84.88.64.86 on Sun, 10 Aug 2014 15:06:46 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Music,

Identity

and the

Inquisition

in

Fifteenth-Century Spain

without

giving

their titles

(e.g.

'las bozes de las oraciones de los

judios').

For the sake of convenience we

may try

to itemise them

as

they appear

in the documents:

1

un

pismoni que

dicen los

judios

Col meuacer

2 la hararu

3 vendiciones cantadas

4 canta el berso

que

dize el

capellan judio quando

saca la

Tora en

hebrayco

5 Mismad

y cohay

etc

6 cadis

7

Vay

hod

lo

asamay

8 el

pizmo

9

algun

salmo

cantado

10 el sediente

The

highly corrupt

character of the

transcriptions

from the

Hebrew in the records tells us a

good

deal about the lack of

sig-

nificance of the individual musical items for Christian notaries. It

must be added that while it is true that these documents are later

copies

of

fifteenth-century originals,

the

mis-transcription

of

Hebrew words or

Jewish

names

by Spanish

notaries is

very

com-

mon

indeed,

even in

fifteenth-century

texts.

Nevertheless,

most of

these references

may

be

identified,

either

by

emendation or

through

their

contexts,

as follows:

1

A

pizmon [see below]

which the

Jews

call

'Qol

Mevaser'

2 the Haftarah

3 the

blessings sung

for the Haftarah

4 Atah Horetah and other verses

5 Nishmat Kol

Hay

6 Kaddish

7 Va-Yekhulu

Ha-Shamayim [i.e.

Kiddush

-

the

Sanctification over the

wine]

8 the

pizmon

9 a

sung psalm

10 'el sediente'2'

21 For this

transcription

of a

prayer's name,

see E.

Gutwirth,

'Fragmentos

de Siddurim

espafioles

de la

Geniza',

Sefarad,

40

(1980), pp.

389-401. The evidence for the musical

character of 'Barukh She-'Amar' and the

practice

of

'prolonging

its tune' is from the

thirteenth

century

and from the Franco-German

region,

and therefore is not

directly

relevant here. Kiddush is transcribed as hedi

(cf.

No.

182)

and also as

beraha. Ata Horetah

is mentioned in Yuda Pillos's

testimony.

Fernan Alvarez's

testimony

refers to the verses

after

removing

the Scroll.

169

This content downloaded from 84.88.64.86 on Sun, 10 Aug 2014 15:06:46 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Eleazar Gutwirth

TALKING ABOUT MUSIC

These references to music in the records of the

Inquisition

reveal

a field which

previously

has not been

developed by

students of late-

medieval

Hispano-Jewish

music,

by articulating,

in

Castilian,

a

specifically Jewish

discourse about music. This

orally

transmitted

and

everyday

material contrasts

sharply

in character from the cor-

pus

of theoretical and learned texts about music in Hebrew from

the

period.

These

generally

refer to music from a

perspective

grounded

in natural

philosophy,

medicine,

cosmology, magic

and

mysticism;

as such

they

are well defined and delimited

by

the con-

ventions of their

respective genres

and textual

sources,

rather than

being spontaneous appreciations

of musical

experience.22

The

Inquisition

records

help

to reconstruct

something

which is not a

staid

repetition

of ancient ideas about music:

rather,

it is a dis-

course -

possibly

more

original

and

certainly

more

spontaneous

-

of

appreciation

and evaluation of musical

experience.

On one

occasion,

for

example,

we are told that

Diego

Arias asked

a

Jew

'whether he knew how to

sing something

in his

Hebrew,

and

he answered that he

did'.23

Music is here not

only

a

question

of

knowledge,

'si

sabia',

but also of

ethnicity,

'su

hebrayco',

where the

possessive pronoun

indicates the converso's

perception

of the

Jews'

'possession'

of Hebrew

language, poetic

texts and

songs. Diego

Arias uses the

termpizmon (transcribed by

the

notary

as

'pismoni'),

and it is of some interest that he does not use other terms.

'Qol

Mevaser' is indeed a

pizmon (the

term was defined

by

medieval

Jews

such as Tanhum Yerushalmi in his

dictionary (s.v. pazzem)

as

the

unchanging

refrain to be

performed

in chorus

by

the audi-

ence),24

but it seems that

by

this time the Hebrew term had

entered the romance vernacular in use in the

daily speech

of

Jews

and conversos as a

generic designation

for

Jewish songs

from the

22

Cf.

e.g.

M.

Idel,

'Music and

Prophetic Kabbalah', Yuval,

4

(1982), pp. 150-69;

N.

Allony,

'The Term

musiqah

in Medieval

Jewish

Literature'

(in Hebrew), Yuval, 1 (1968); I. Adler,

ed.,

Hebrew

Writings Concerning

Music

(Munich, 1975).

23 FIRC No

104, p.

62. Another witness described an occasion when

Diego

Arias was

singing

'a

una sola voz'

(solo)

in Hebrew and all the others

responded.

See FIRC No. 71. Another

description

of his

singing

was 'a

voces',

i.e.

loudly.

See FIRC No.81.

24

H.

Shay's

critical edition of the

dictionary

on the basis of the St

Petersburg

and other

Geniza

fragments

is imminent. In the

meantime,

see the

quotation

and comments of

Y.

Ratzhavi,

'Form and

Melody

in the

Jewish Song

of Yemen'

(in Hebrew), Tazlil,

8

(1968), p.

16.

170

This content downloaded from 84.88.64.86 on Sun, 10 Aug 2014 15:06:46 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Music,

Identity

and the

Inquisition

in

Fifteenth-Century Spain

liturgy.

Another witness tells us how 'the said

Diego

Arias

helped

him and said that he did not

get

the

melody right

but that it was

the

way

he started to

sing,

and then

they

both

sang':25 'ajudo' may

have little

meaning beyond 'helping'

but it

may

also be a term

with resonances from

synagogal

institutions where a

'helper'

of

the

precentor (hazzan)

acted as a one-man

choir.26

Another

Jewish

witness described

Diego

Arias's

performance

as follows: 'cantalo

muy

bien

y

bienelo cantando

paso

a

paso',27 using Spanish

musi-

cal

terminology;

even

today

the

expression 'paso

a

paso'

retains

the

meaning

of 'cada una de las mudanzas

que

se hacen en un

baile',

although

it also denotes the

precision

and deliberate

pace

of an

activity.

In another case a witness described the

Jewish liturgy

using

the term

responso

taken from the Christian

liturgy:

'he

began

to

sing

a

responso

which the rabbi

sings

at the

beginning

of the

prayer

"Mismad

y cohay"

.. .'28 or, elsewhere,

'to

say

the said

respon-

sos'.

In modern

Castilian,

responso

has a

relatively

wide

range

of

associations;

not

only 'responsorio que separado

del rezo se dice

por

los

difuntos',

but also 'ciertas

preces y

versiculos

que

se dicen

en el rezo

despues

de las lecciones en los maitines

y despues

de

las

capitulas

de otras horas'. In another

testimony

made before

the tribunal we read that 'he

began

to

sing according

to his voice

a

responso

which he

sang very tunefully

as the

Jews

do and with as

much

grace

or even better ... for about a

quarter

of an

hour'.29

(Note

that this witness used the

phrase

'mucho a son'

-

'in

tune'.)

So the

impression

left on this

Jewish listener,

Jacob Castellano,

more than two decades after the

performance

was not

only

musi-

cal but was also

inseparable

from

ethnicity: Diego

Arias

sang

'en

la forma

que

los

judios

lo dicen

y

con tan buena

gracia

o

mejor':

'as

the

Jews

do and with as much

grace

or even

better'.30

25 FIRC No.

104, p.

62.

26

R. Solomon ben

Adret, She'elot W-Teshuvot,

vol. I

(Bne Beraq, 1982), p. 300,

refers

repeat-

edly

to 'the

helper'

of the Huescan

community's precentor.

I

interpret

the references

to

'helper

as

replacement'

of the cantor as

only

one

aspect

of the

'helper's'

functions.

27 FIRC No. 111.

28 FIRC No.

179, p.

102.

29

FIRC No.

187, p.

166.

30 Ibid.

171

This content downloaded from 84.88.64.86 on Sun, 10 Aug 2014 15:06:46 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Eleazar Gutwirth

MUSIC AND SOCIETY

These considerations

bring

us to the more

general question

of the

significance

of

Diego

Arias's

performance

of Hebrew

songs.

While

on the one hand the music of the

Jews

and the conversos has not

been a

subject

of much interest to students of the records of the

Inquisition,

on the other the

study

of conversos' activities in

general

is a field with a

long history.

Some

attention,

albeit

brief,

to the

positions expressed

in the

historiography

of the

subject

is neces-

sary

to

clarify

some of the

ways

in which it contrasts with our own.

As is well

known,

there are a number of studies of what are usu-

ally

termed the 'ritos

y

costumbres'

(rites

and

customs)

of the con-

versos.3'

These

bring together reports

from the

Inquisition's

records

from the 1480s

onwards,

in which witnesses describe what

they

believe to be the

'judaising' practices

of

neighbours

or

acquain-

tances,

such testimonies

usually being

used

by

the

prosecution.

Students of

Spanish history

in the

period

of the

Inquisition

have often used these accounts as evidence of the

'judaising'

or

'Judaism'

of the conversos. The reader of such studies cannot

help

forming

the

impression

that there is a certain

homogeneity

about

their

description

of these

practices,

that is to

say

that

they

func-

tion

through

a

general category

of

'judaising'

or

'Judaism' (depend-

ing

on the

writer)

and that all the 'rites and customs' are more

or less similar and

equally placed examples

or

exponents

of this

general category.

Our

particular

case,

that of music

performances

as recorded in

the file of

Diego

Arias,

is related to

(though

not identical with -

see

below)

a defined and

particular

field,

namely liturgy.

Within

the conventions of the

study

of the conversos based on

Inquisition

records,

these cases of

singing Jewish prayers belong

to a

general

homogeneous

and somewhat

shapeless category

of 'rites and cus-

toms'. If we cannot follow these

historiographic

traditions,

it is in

part

because the

apparent shapelessness

and

homogeneity

of the

resulting image

thus constructed trivialises the

importance

of the

evidence and is belied

by

the methods

adopted

in related and

neighbouring

areas of recent

research,

such as the

history

of

Christian

andJewish liturgy.

Indeed,

historians of

liturgy

know full

31 R. Santa

Marfa,

'Ritos

y

costumbres de los hebreos

espafioles',

Boletin de

la

Real Academia

de

la Historia,

22

(1893), pp.

181-8,

is an

early exponent

of this

long

tradition.

172

This content downloaded from 84.88.64.86 on Sun, 10 Aug 2014 15:06:46 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Music, Identity

and the

Inquisition

in

Fifteenth-Century Spain

well that not all

prayers

are identical or

interchangeable,

and that

there are

categories

of

prayers,

functions, placement

and devel-

opments

within

liturgy.

It is

only

too

easy

to ascribe these con-

tradictions to a technical

explanation, namely

that students of

Spanish paleography,

medieval documents and

fifteenth-century

Romance - i.e. the

general

historians of the conversos' 'rites' - have

been unaware of the

corpus

of

scholarship dealing

with

Jewish

liturgy

in Hebrew in

general

and of the intense late-medieval

pro-

ductivity

of codification of

Hispano-Jewish liturgy

in

particular.

Conversely,

students

ofJewish liturgy

have had little contact with

these medieval documents or with detailed studies of the conversos

of

fifteenth-century Spain.

Yet such an

explanation,

while it is

partly

true,

does little

justice

to the more

profound problem

touched on

by

such students of

liturgy

as,

for

example,

Hoffman.32

He has

recently

written on the difficulties of

describing religious

experience

and

appropriately

cites

Wittgenstein,

who observed

that it is

impossible

for the

non-religious person

to contradict

the

religious. Putting

himself in the

position

of the

former,

Wittgenstein

writes:

I think

differently...

I have different

pictures

...

[In attempting

to con-

tradict a

religious person]

I

give

an

explanation:

'I don't believe in

...

but the

religious person

never believes what I describe. I can't

say.

I can't

contradict the

person

.. .' We work with different

pictures

that we take

for

granted

and with which we order

experience.33

Perhaps unwittingly,

students of the conversos'

practices

seem to

have

adopted

the

Inquisitors' point

of

view,

in as much as all these

practices

have been considered to be

equally

indicative of the

'heresy'

of

'judaising'.

But for the

twentieth-century

historian who

wishes to come to terms

seriously

with the

understanding

of the

significance

of the

songs

ofconversos such as

Diego Arias,

mere

para-

phrase

of the

Inquisition

records is not

sufficient,

despite

the ven-

erable

historiographic

tradition that lies behind it. Historians who

search for some coherence in these

apparently incongruous

lists

(which

include both

morning

and

evening liturgies,

festivals and

the

Sabbath),

rather than

adopting

the

Inquisitor's perspective,

might

turn instead to recent

scholarly

research in the field of

32 L. A.

Hoffman, Beyond

the Text: A Holistic

Approach

to

Liturgy (Bloomington, Indiana, 1987),

p.

36.

33

Hoffman,

Beyond

the

Text, p.

37.

173

This content downloaded from 84.88.64.86 on Sun, 10 Aug 2014 15:06:46 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Eleazar Gutwirth

liturgy.

Here much recent

writing

has

expressed

a certain dissat-

isfaction with exclusive concentration on the texts of the

liturgy,

and has tried to create a more inclusive

approach

which takes the

worshipper's experience

into account. This

trend,

it

might

be

argued,

is not

entirely

dissimilar to the historians' dissatisfaction

with the incoherent and

heterotopic

lists of 'rites and customs'.

Hoffman34

speaks

of the

process

of

discovering

some

underlying

message

that a

prayer

communicates

despite

variations in its

spe-

cific

wording.

That is to

say

that a first

step

in

moving away

from

traditional studies of the

Inquisition

records would be to

pay

some

attention to the

liturgical

status of converso music.

The 'Col meuacer' of the

Inquisition

file is a

liturgical poem by

the

seventh-century poet

Eleazar

Ha-Qalir;

as such it is an addi-

tion to the

original

older

liturgy

which

belongs

to the

prayers

for

rain on Hoshana

Rabba,

the

penultimate day

of the Feast of

Tabernacles. There is no evidence in the text that the occasion on

which Samuel and

Diego

were

walking

with other

people

was that

particular

feast. Neither of them was

fulfilling

a

religious

com-

mandment

by singing

in a

duo,

separated

from a

quorum.

Another

example

would be the

testimony

about the

prayer

shawl:

'Diego

Arias

quando

esta de

gorja

o

de

placer

... toma una

gran

toca

y

ponesela

sobre los hombros e cabeza a forma de taler.' To

put

on

'a

great

shawl' is not

fulfilling

the commandment of sisit or tas-

sels. In

fact,

if the cloth has four

corners,

has a certain measure

and has no

sisit,

a

Jew wearing

it

might

be

transgressing

the com-

mandment.

The

phrase

'a forma de taler' indicates that it was not

a talit

proper.5"

Diego

Arias was not

fulfilling

a

religious

com-

mandment

by putting

a tablecloth over his head in an inn in

Medina del

Campo.36

Another witness tells us that

Diego

'canta

el berso

que

dize el

capellan judio quando

saca la Tora en

hebrayco

y

cantalo

muy

bien

y

bienelo cantando

paso

a

paso

como el

capel-

lan

faze

quando

saca la

Tora'.37 Diego

Arias,

who was not

taking

34 Hoffman, Beyond

the

Text, pp.

36ff.

35

FIRC No. 111.

Another version which circulated in

Segovia

was that it was a bedsheet

- 'sabana'

- rather than a tablecloth. See FIRC No. 77. David Gome's

testimony

is that

'en

aquellos

mesmos dias

los

decia

el

dicho

Diego

Arias'

('he

said it on those

very days'),

p.

102. This seems to be the

exception

to the

general

rule

of not

specifying

the

liturgi-

cal season.

36 FIRC No.

179, p.

102.

37

FIRC No. 111.

174

This content downloaded from 84.88.64.86 on Sun, 10 Aug 2014 15:06:46 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Music,

Identity

and the

Inquisition

in

Fifteenth-Century Spain

out a Torah scroll from the

Ark,

was not

engaging

in a

liturgical

act. But for the readers of these records it

might

be

helpful

to

bear in mind that some of the verses to be recited on the occasion

of the

taking

out of the Torah from the Ark on the Sabbath morn-

ing

and festival

morning prayers

are

relatively

late

additions,

which some medieval

congregations thought

to be tiresome

[tiruhah].

They

have

recently

been discussed

by

historians of the

liturgy.

For

Reif,38

the addition of these verses to the

liturgy

is a

manifestation of an

important

trend related to the

history

of

SpanishJewry

in this

period and,

more

precisely, according

to

Reif,

to the search for

grandeur

and institutionalisation. Such a devel-

opment

is

expressed in,

amongst

other

fields,

that of late-medieval

Hispano-Jewish architecture,

where 'the

styles

of the

synagogues

became more elaborate and absorbed at least some limited amount

of the

grandeur

of their

neighbours'

houses of

worship'."

It

may

be concluded that this

example

- like various other acts which

neighbours

or

inquisitors,

or even certain modern students of

Inquisition records,

might

have

thought

to be 'rites and customs'

of the

Jews

- turns

out, upon

an

inspection

which does not

ignore

Jewish liturgical

codification,

to be

something

else

entirely.

Diego

Arias's musical tastes were not restricted to the Arabic

songs

with

which,

according

to Palencia's account and Menendez

Pidal's

analysis,

he

captivated

audiences in the

countryside

around

Segovia during

his

youth.

Nor does an awareness of

Jewish

litur-

gical practice permit

us to describe his

performance

of

Jewish

songs

as

merely

the fulfilment

ofJewish liturgical

duties. It seems

quite

clear that we are confronted with a case of what

may

be

called 'cultural

identification',

in which the converso

perceives

music

that was

originally liturgical

as an

expression

of ethnic and cul-

tural

identity.

The

equivalent

in the field of music to the litur-

gists' attempt

to reconstruct the

liturgical experience

as a whole

(rather

than

just

its

texts,

isolated from

any

human

experience)

would be to take into account the

experience

of

performance,

something

that could be done

by considering

the late-medieval

Hispano-Hebraic

evidence. This also involves

searching

for a

'shape'

to the musical

experience,

however difficult such a search

may

be and however distanced from the

shapeless

list

provided by

38

S.

C.

Reif,Judaism

and Hebrew

Prayer (Cambridge, 1993), p.

210.

39

Ibid.

175

This content downloaded from 84.88.64.86 on Sun, 10 Aug 2014 15:06:46 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Eleazar Gutwirth

Inquisition

notaries. The search for such

'shapes',

forms or struc-

tures

is, however,

an

integral part

of the work in the field of litur-

gical history; liturgists

themselves

speak

of

'introductory' prayers

and 'final'

prayers,

of

prayers

as 'the form of communal

expres-

sion',

and so forth.40

These are not the

approaches

of the 'Ritos

y

Costumbres' school.

Rather,

they attempt

to understand the

worshipper's

different

experiences

of different

prayers.

A careful

reading

of the evidence

suggests

that Arias's

fifteenth-century contemporaries

were aware

of the

particular

character of

any given

musical

performance.

Thus,

one witness remarked that

Diego's singing

was done when

he was 'de

gorja

o

de

plazer',41

and however

simplistic

that

opin-

ion,

it does show that

contemporaries

were well aware of some

particular

state of mind or attitude related to

singing.

'De

gorja',

however,

also has some further associations.

Covarrubias,

who was

closer to

Diego's language,

recalled the associations of these same

words in terms which denote a

pre-linguistic stage.

Derived from

the Latin

gurges,

it refers to the

singing

bird's throat or to the child

'who wishes to

speak

and

attempts

it without

using

other instru-

ments'.42

Similarly,

the

meaning

of

'scoffing',

a characterisation of

Diego

Arias's

singing by

another

witness,

refers to a deliberate

message

in the

singing.

Somewhat closer to the mark was the

implication

of another

witness,

Don Abraen

Seneor,

who on 21

April

1486 'said that he had heard

many

who lived with

Diego

Arias

...

that he

sang

in Hebrew in order to contrahacer the

singing

of the

Jews'.43

Here Abraham Seneor uses the verb contrahacer to

describe the character of

Diego

Arias's

music,

which is to

say

that

a

Jewish contemporary

of

Diego

Arias

may

be said to be

alluding

to a musical

phenomenon

which has

counterparts

in a number of

medieval cultures. In a related

area,

that of

literature,

it

may

be

noted first of all that Hebrew

poetry

had used the contrafacta

mode from a

very early

date,

and that in

Spain

the use of themes

or metres taken from Hebrew secular love

poetry

in the

composi-

tion of

religious

and

liturgical poetry

in Hebrew is

particularly

well

documented for the eleventh and twelfth centuries. The Hebrew

40

Ibid.

41 FIRC No. 111.

42

Covarrubias,

Tesoro de la

lengua espafiola (Madrid, 1610) s.v.

gorja.

43

FIRC No.

190, p.

107.

176

This content downloaded from 84.88.64.86 on Sun, 10 Aug 2014 15:06:46 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Music,

Identity

and the

Inquisition

in

Fifteenth-Century Spain

liturgical

or

religious

muwashahat

or

paramuwashahat

are classic

examples.

But even in the fifteenth

century

a

poem

could be writ-

ten in a conscious

attempt

to create a variation on an earlier

poem.

The case of Bonafed's dream

poem

or his

'muwashshah

in the form

of a

mustagib' (that

is to

say,

a love

song

in a form

usually

used in

the

composition

of

penitential liturgical hymns)

are

examples

from

Saragossa dating

from the first half of the fifteenth

century.44

In

Christian

Spain,

the

literary

textual

parody

of the canonic hours

in the Libro de buen amor or the 'vuelta a lo divino' of

popular songs,

especially

the

villancicos,

are well-known cases of what

may

be

termed a constant movement between sacred and

profane

written

texts.45

Perhaps

more relevant is the case of the

incipits

or tune

markers of

fifteenth-century

Hebrew lamentation

poems

which

inform us about the

non-Jewish

melodies used in Hebrew

prayer.

These are

similarly

relevant

examples

of the

currency

of

phe-

nomena related to musical contrafacta in

Diego

Arias's time.46

This

recognition

of the need to

study

the resonances of the

music,

rather than trivialise

it,

is

similarly

the

underlying assumption

of

Tess

Knighton's

search for and successful identification of the

tunes of the troubadours which underlie some of the

compositions

of

fifteenth-century Spain

and their cultural context.47 Romeu's

extensive discussion of the

transposition

of secular and

religious

themes and melodies in the

songs

of the Cancionero de Palacio

may

be relevant even if the dates of the

compositions

are at times some

decades later than

Diego

Arias's death.48

Such features of musical

44

E.

Gutwirth,

'A

muwashshah

by

Solomon

Bonafed',

ed. A.

Sienz

Badillos,

Actas ...

Congreso

Poesia

Estr6fica

(Madrid, 1991), pp.

137-44.

45 O0.

Green,

'On

Juan

Ruiz'

Parody

of the Canonical

Hours', Hispanic Review,

26

(1958),

pp. 12-34;

M. P. Saint

Amour,

A

Study of

the Villancico

up

to

Lope

de

Vega:

Its Evolution

from

Profane

to Sacred Themes and

Specifically

to the Christmas Carol

(Washington, 1940);

M.

Frenk,

Entrefolklorey

literatura

(Mexico, 1971), pp. 58-63;

F.

Marquez Villanueva, Investigaciones

sobreJuan

Alvarez

Gato

(Madrid, 1960); J. Rodriguez Putrtolas, Fray Ifligo

de Mendoza:

Cancionero

(Madrid, 1968) pp.

xxvi

ff.

46

E.

Gutwirth,

'Language

and

Hispano-Jewish

Studies'

(in Hebrew), Pe'amim,

41

(1989),

pp.

156-9.

47

T.

Knighton,

'New

Light

on Musical

Aspects

of the Troubadour

Revival',

Plainsong

and

Medieval

Music,

2/1

(1993), pp.

75-83.

48 La mz'sica en la corte de los

Reyes

Catdlicos

(siglos XV-XVI),

vol. iv-i: Cancionero de

Palacio,

introducci6n

y

estudios

por J.

Romeu

Figueras (Barcelona, 1965), cap.

v. For him the

songs

of the Cancionero de Palacio are like Proven<al troubadour and

goliardic poetry

in

their

hyperbolic

use of divine

metaphors

and in their

employment

of the

language

of

devotion in

speaking

of

profane

love. Thus we find a bacchic

song

which is a

parody

of

a Marian

hymn;

love

masses;

the

agony

of love

depicted

in terms taken from the litur-

gical

offices of Easter and the

dead;

and the

gospels quoted

in

profane

love

songs.

177

This content downloaded from 84.88.64.86 on Sun, 10 Aug 2014 15:06:46 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Eleazar Gutwirth

sensibility

did not

change overnight.

These are

by

no means iden-

tical with

Diego

Arias's case. He was

certainly

not

turning any-

thing

'a lo

divino',

but neither was he

creating

an erotic

parody

of

the

liturgy.

However,

such

comparisons help

us to

get

closer to the

mentality

from which

sprang

his 'contrahacer'

-

to use Seneor's

term. It

may

be

argued

that the most relevant

parallels

are those

late-medieval cases where

religious

music is

performed

in secular

settings

with secular

(such

as

regional

or

political)

or at least non-

liturgical messages

or functions. The studies of

Christopher Page

are a most useful case in

point.

As he writes: 'The idea of

hymn-

melodies torn from their

liturgical setting

and set adrift in a world

of domestic and

public performance

need not

surprise us;

John

Stevens

pointed

out

long ago

that some

plainsong hymns

had cur-

rency

as

popular songs

in later-medieval

England.'49

In

his research

on the music of the Thomas of Lancaster

cult,

Page points

out

that 'When clerics familiar with the use of Hereford

sang

Lancaster's

piece

a wealth of

liturgical meaning

would be released

and channelled into the new

cult,

Thomas would be

implicitly

com-

pared

with St Ethelbert ... the

parallels

would

assuredly

not be

seen as

accidental;

he would also be assimilated to his

namesake,

Thomas of

Hereford.'50

The case of

Diego

Arias,

rather than

being

an

example

of one of the usual

literary

textual

contrafacta,

is

pre-

cisely

one of

'hymn-melodies

torn from their

liturgical setting

and

set adrift in a world of domestic and

public performance'.

But what

could be the 'wealth of

liturgical meaning'

that 'would be released

and channelled'

by Diego

Arias's

singing?

In this

context,

bearing

in mind the difference in the

pace

of

research in these different

fields,

it

may

be

possible

to

suggest

some

possibilities

for

understanding

the

way

in which

Enrique

IV's

courtier could have

perceived

the vocal music he

performed

and,

by implication,

how to treat such evidence in

general.

The first

possibility might

be a musical one.

Although

the music

is

lost,

we do have some

pointers

and musical traditions. It is also

evident from the context that these

prayers

were

sung,

and

nowhere is there a sense that it was the music itself that was an

49 J. Stevens,

Music and

Poetry

in the

Early

Tudor

Court,

2nd edn

(Cambridge, 1979), p. 50;

C.

Page,

'The

Rhymed

Office for St Thomas of Lancaster:

Poetry,

Politics and

Liturgy

in

Fourteenth

Century England',

Leeds Studies in

English (NS),

14

(1983), pp.

134-51.

50

Page,

'The

Rhymed Office', p.

138.

178

This content downloaded from 84.88.64.86 on Sun, 10 Aug 2014 15:06:46 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Music,

Identity

and the

Inquisition

in

Fifteenth-Century Spain

innovation.

(We may

recall that 'Nishmat' is described as a

song

as

early

as the

Babylonian

Talmud,

where in BT Pes.118a it is

called a

'song',

birkat

ha-shir.)

Some of the others have

preserved

a musical character to this

day.

The second

possibility

would focus

upon

the

question

of mem-

ory.

The converso's

singing

was related to and relied on the earli-

est sources of his

identity, namely

his documented

Jewish

childhood. The

songs

were

memorable,

it

may

be

argued,

because

most of them had

something

in common.

They

were

accompanied

by

some

symbolic

action which set them

apart

in his

memory

from

the rest of the

liturgy.

In the case of

'Qol

Mevaser' the action is

the

hitting

of the branches -

hoshanot

-

although Diego

Arias was

doubtless unaware of and uninterested in its

probable early

func-

tion as a

magic

ritual which imitated the sound of the rain. But

it would doubtless

(because

of its

impacting character)

leave an

indelible trace on the

memory

of a

Jewish

child

who,

like

Diego

Arias,

attended services. The

raising

of the wine

cup

at the

Kiddush

ceremony

would be a similar

case,

and the ascent to the

Torah of

young

men at

puberty

would be

equally

memorable. The

solemn

ceremony accompanying

the removal of the Torah scroll

from the

Ark,

prior

to the

reading,

is an

equally symbolic

and dra-

matic action.

The third

explanation

would

similarly

have to do with the

expe-

rience of music

by

the

congregation

and,

more

precisely,

with the

deeper

structures of the

liturgy,

in this case the

position

of the

individual

songs

within it. Thus