Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

58-4 Scottish Maid

Caricato da

manu-arrb100%(2)Il 100% ha trovato utile questo documento (2 voti)

636 visualizzazioni4 pagineThe schooner evolved as a dominant force in British merchant shipping during the early nineteenth century. Because of the ships' relatively small size, shallow draft, and excellent speed, they were well suited to the fruit trade. Model ship builder John G. Heard began with kit construction on a card table in a closet as a method of relaxation during his medical training.

Descrizione originale:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoThe schooner evolved as a dominant force in British merchant shipping during the early nineteenth century. Because of the ships' relatively small size, shallow draft, and excellent speed, they were well suited to the fruit trade. Model ship builder John G. Heard began with kit construction on a card table in a closet as a method of relaxation during his medical training.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

100%(2)Il 100% ha trovato utile questo documento (2 voti)

636 visualizzazioni4 pagine58-4 Scottish Maid

Caricato da

manu-arrbThe schooner evolved as a dominant force in British merchant shipping during the early nineteenth century. Because of the ships' relatively small size, shallow draft, and excellent speed, they were well suited to the fruit trade. Model ship builder John G. Heard began with kit construction on a card table in a closet as a method of relaxation during his medical training.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 4

NAUTICAL RESEARCH JOURNAL 271

Figure 1. Scottish Maid. Model and photographs by the author.

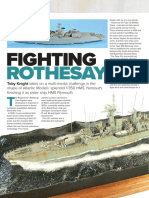

The English Merchant Schooner

Scottish Maid

. . . . .

by John G. Heard, M.D.

The schooner evolved as a dominant force

in British merchant shipping during the

early nineteenth century. The British devel-

oped the topsail schooner, setting square

sails from yards on the foretopmast, which

allowed better response to the varying wind

direction in local waters than was possible

with fore and aft rigs. The schooners were

built economically in small ports, and were

quite seaworthy, allowing both coastal trade

and long ocean passages. Because of the

ships relatively small size, shallow draft,

and excellent speed, they were very well

suited to the fruit trade that developed

between Britain and the Azores, supplying

oranges and other perishables to home

ports. These ships were beautiful and sport-

ed wonderful names such as Geisha and, my

favorite, Fruit Girl. The schooners were also

well suited to the packet trade, moving pas-

sengers and valuable cargo to and from

London, bypassing the rough roads and cut-

Vol. 58, No 4 WINTER 2013

272

ting travel time.

I have found that model ship builders

gradually adopt styles and methods of con-

struction over the course of the years, and

become focused in specific areas of expert-

ise. I began with kit construction on a card

table in a closet as a method of relaxation

during my medical training. A pivotal event

in my development occurred when I read

Harold Underhills two volume work, Plank

On Frame Models, and followed his teach-

ing in the construction of a scratch built

model of Leon. Over the next years I

became interested in English merchant

schooners, and have finished several models

of these ships. There is a great pleasure in

having all of your effort and experience

focused on one type of ship, and for me this

culminated in Scottish Maid.

Scottish Maid was built in Aberdeen,

Scotland, in 1839 by Alexander Hall & Sons

as a packet schooner for the London trade.

This was the first schooner designed with

the Aberdeen bow, a heavily forward raked

stem designed to gain unmeasured cargo

space under the new measurement rules

instituted by the government in 1836. The

new bow increased speed and improved sail-

ing characteristics. The Halls subsequently

built many ships based on the design,

including Elissa, launched in 1877 and still

sailing out of the Texas Seaport Museum in

Galveston, Texas.

Figure 2. Scottish Maid deck view.

Figure 3. Port side bow view.

NAUTICAL RESEARCH JOURNAL

273

The Halls used a builders half model

to construct Scottish Maid, which David R.

MacGregor later used to produce complete

lines, deck, and sail plans. I used these

plans in creating this model, which is con-

structed to Class A scratch built standards.

All parts of the model except the rigging line

were made from scratch. The hull and

frames are cherry and the decking is lemon-

wood. The smaller partssuch as rigging

blocks, the anchor, gratings, and the ships

boatrequired the use of fine grain box-

wood. Most of the metal parts were made of

blackened brass. The model is made in

Admiralty style with exposed frames below

the waterline. The frames are replicas of the

actual frames, made of mutually supporting

pairs with butting of five to seven parts in

each frame. The planking follows Lloyds

Registration Rules for overlap of joints. The

scale is 1:96, suggesting that one must build

everything one can see with the naked eye

one hundred feet away from the actual ship.

The model was constructed on a -

inch plywood board with blocks to locate the

position of the keel and vertical brackets at

either end to grip the keel, stem, and count-

er. This allows the model to be constructed

in a controlled vertical plane similar to the

actual ship construction method, and the

hull can be removed from the jig at any time

during construction for detailed work. Each

frame was lifted from the lines plan, allow-

ing for planking thickness and the bevel of

the outside edge of the frame. Construction

began with fixing the midship frame to the

keel and progressed forward to the stem and

aft to a special built up counter. A template

board was used to hold the upper part of the

frames in proper position during construc-

Figure 4. Stern view.

Figure 5. Starboard side overhead view.

Figure 6. Starboard view.

Vol. 58, No 4 WINTER 2013

274

tion.

Dowels used for hull construction

and the planking treenails were made from

bamboo stakes, obtained from a local garden

shop, and drawn to correct size through a

jewelers draw plate. The stanchions were

inserted between frames in the real ship, but

I included them as extensions of the frames

to maintain the sweep and contour of the

hull in the model. The deck planking was

applied in single strips, blackened on the

edge with a #2 pencil to represent caulking.

Deck furniture was finished to scale, and

small metal parts were fabricated from

blackened brass using low temperature sol-

der with flux. One of the most delightful

items to build was the ships wheel, made

from a boxwood rim with bamboo spokes.

Just when I thought I had wrapped

up the deck, I remembered the ships boat,

which, to scale, measured about three inch-

es in length. There are several approaches to

building small boats, but I prefer the plank

on plug method. From the lines drawing of

the boat, a scale plug was carved from bass-

wood and coated with wax. A 1/32-inch box-

wood keel, stem piece, and sternpost with a

transom were inserted into a centerline

groove in the plug, which then was planked

over with boxwood. I added internal fittings

after the boats hull was removed from the

plug.

With the hull finished, masts and

spars were turned from cherry on a lathe

and small metal parts and lines were added.

Single and double rigging blocks were made

from boxwood in the correct sizes. Deadeyes

for the main rigging were made to scale

from cherry. Belaying pins were made from

bent, soldered, and shaped brass wire. The

rigging was taken from MacGregors sail

plan with few changes.

It took me one and a half years to

research and build this model from scratch.

One must ask oneself if it was worth all that

time. The answer lies in the reward the

builder finds in each element of the process,

and his or her focus on each part of the puz-

zle. Harold Underhill said it best: For me

the real pleasure is in the work of building

rather than the model when complete.

John G. Heard, M.D. practiced radiology and

nuclear medicine for many years. After

retirement from medicine, he switched from

X-ray to the visible spectrum and worked in

stage lighting design. A long time interest in

sailing was channeled by the writings of

Harold Underhill into scratch building

model merchant ships, and these efforts are

aided by his participation in the Gulf Coast

Ship Modelers Society.

References:

Greenhill, Basil, The Merchant Schooners, 2 vol-

umes. London: Conway Maritime Press, 1988.

Hamby, D., Scottish Maid, Model Shipwright 94

(December 1995), 60-66.

Lloyds Survey Report no. 560, National Maritime

Museum, Greenwich, England

MacGregor, David R., Fast Sailing Ships: Their

Design and Construction, 1775-1875. Lymington:

Nautical Publishing Co., 1973.

-Scottish Maid Lines, Deck, and Sail Plan.

David MacGregor Plans.

Underhill, Harold, Plank On Frame Models, 2 vol-

umes. Glasgow: Brown, Son, & Ferguson, 1974.

Figure 7. Port side view.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Ship Models from the Age of Sail: Building and Enhancing Commercial KitsDa EverandShip Models from the Age of Sail: Building and Enhancing Commercial KitsNessuna valutazione finora

- 23 - Msbj-2011-MayDocumento31 pagine23 - Msbj-2011-Mayanon_835518017Nessuna valutazione finora

- Catalog Modelshipfactory EnglishDocumento25 pagineCatalog Modelshipfactory Englishgigialex72100% (1)

- Davis C.G., Steel D.R. How To Make Ship Block Models, 1946 PDFDocumento89 pagineDavis C.G., Steel D.R. How To Make Ship Block Models, 1946 PDFНиколай Латышев100% (1)

- A Model Boat Builder's Guide to Rigging - A Collection of Historical Articles on the Construction of Model Ship RiggingDa EverandA Model Boat Builder's Guide to Rigging - A Collection of Historical Articles on the Construction of Model Ship RiggingNessuna valutazione finora

- Ship Modeling Simplified Part 4Documento7 pagineShip Modeling Simplified Part 4boidar kanchevNessuna valutazione finora

- 45 MSBJ 2016 SpringDocumento47 pagine45 MSBJ 2016 Springanon_835518017Nessuna valutazione finora

- Marine Modelling Int 2012-10Documento76 pagineMarine Modelling Int 2012-10nex71Nessuna valutazione finora

- Hahn MethodDocumento2 pagineHahn MethodLucianNessuna valutazione finora

- Dressel D. Rigging TechniquesDocumento209 pagineDressel D. Rigging TechniquesYesedavilaNessuna valutazione finora

- 39 - Msbj-2014-July PDFDocumento32 pagine39 - Msbj-2014-July PDFanon_835518017Nessuna valutazione finora

- Just Add WaterDocumento3 pagineJust Add WaterDragan SorinNessuna valutazione finora

- Model Boats - Vol. 69 No. 830, December 2019Documento76 pagineModel Boats - Vol. 69 No. 830, December 2019ryanNessuna valutazione finora

- Wood Ship Kits & Ship Modeling For BeginnersDocumento6 pagineWood Ship Kits & Ship Modeling For BeginnersExclusive Wooden Ship Kits Online0% (2)

- Ship Reportn9oDocumento3 pagineShip Reportn9oyanz687Nessuna valutazione finora

- Model Airplane News 1931-03Documento52 pagineModel Airplane News 1931-03Thomas KirschNessuna valutazione finora

- 02flying Models February 1990 PDFDocumento101 pagine02flying Models February 1990 PDFandres silvestreNessuna valutazione finora

- H.M. B V G 1756: OMB Essel RanadoDocumento62 pagineH.M. B V G 1756: OMB Essel RanadoWanderson NavegantesNessuna valutazione finora

- H.M.H.S BritannicDocumento20 pagineH.M.H.S BritannicEnrico Miguel N SalvadorNessuna valutazione finora

- 36 - Msbj-2014-Jan PDFDocumento23 pagine36 - Msbj-2014-Jan PDFanon_835518017Nessuna valutazione finora

- MSB113 Planking The Build-Up Ship ModelDocumento40 pagineMSB113 Planking The Build-Up Ship ModelDionysis NtreouNessuna valutazione finora

- Vintage Airplane - May 1974Documento20 pagineVintage Airplane - May 1974Aviation/Space History Library100% (1)

- Msbjournal November 2010Documento28 pagineMsbjournal November 2010anon_835518017Nessuna valutazione finora

- 44 MSBJ 2015 WinterDocumento43 pagine44 MSBJ 2015 Winteranon_835518017Nessuna valutazione finora

- Slat ArmorDocumento11 pagineSlat ArmorGeorge SmithNessuna valutazione finora

- 01model Airplane News January 1950Documento51 pagine01model Airplane News January 1950Thomas KirschNessuna valutazione finora

- Marine Modelling 2011-09Documento76 pagineMarine Modelling 2011-09AericNessuna valutazione finora

- Scratchbuilding Concrete Bridge PiersDocumento9 pagineScratchbuilding Concrete Bridge PiersrwaidaabbasNessuna valutazione finora

- Bismarck3den PDFDocumento19 pagineBismarck3den PDFi_kostadinovic100% (1)

- Info Eduard 2012 10ENDocumento32 pagineInfo Eduard 2012 10ENMrZaggyNessuna valutazione finora

- Airfix Model World 2022-10-52-59Documento8 pagineAirfix Model World 2022-10-52-59zio_nanoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Vasa ResurrectionDocumento3 pagineThe Vasa ResurrectionMary Eloise H LeakeNessuna valutazione finora

- HMS Kingfisher - Plank On Frame PDFDocumento96 pagineHMS Kingfisher - Plank On Frame PDFGabryelbrutusNessuna valutazione finora

- 12MB December 1980Documento107 pagine12MB December 1980Walter GutierrezNessuna valutazione finora

- Flying Scale Models 2020-02Documento68 pagineFlying Scale Models 2020-02Pippo100% (1)

- Airfix Club Magazine 18Documento16 pagineAirfix Club Magazine 18SilverioNessuna valutazione finora

- Voie Libre 2018-10Documento74 pagineVoie Libre 2018-10javis77100% (2)

- 01 S-Boats Part II - The Government Boats PDFDocumento14 pagine01 S-Boats Part II - The Government Boats PDFFrank MasonNessuna valutazione finora

- Blitzscales 15Documento68 pagineBlitzscales 15SilverioNessuna valutazione finora

- 2023 03 01GreatScaleModeling2023Documento100 pagine2023 03 01GreatScaleModeling2023murray.hutchisonNessuna valutazione finora

- Constructing A Model of A ShipDocumento10 pagineConstructing A Model of A ShipAsnawirNessuna valutazione finora

- Info Eduard 2010 07ENDocumento30 pagineInfo Eduard 2010 07ENLuke WangNessuna valutazione finora

- The Rudder Volume 25Documento601 pagineThe Rudder Volume 25Kilian Walsh100% (1)

- Model Military International Issue 198 October 2022Documento70 pagineModel Military International Issue 198 October 2022nomader56Nessuna valutazione finora

- Getting Started in Proto 87Documento48 pagineGetting Started in Proto 87peNessuna valutazione finora

- 46 MSBJ 2016 SummerDocumento30 pagine46 MSBJ 2016 Summeranon_835518017Nessuna valutazione finora

- 000Dr Mikes ModelShipBuilding Gallery EBookمخططات PDFDocumento52 pagine000Dr Mikes ModelShipBuilding Gallery EBookمخططات PDFAbdou BouguerriNessuna valutazione finora

- Msbjournal April 2008Documento29 pagineMsbjournal April 2008mhammer_18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Model Airplane News - January 2011 - RC Heli DergisiDocumento68 pagineModel Airplane News - January 2011 - RC Heli DergisiDarren-Edward O'Neill100% (1)

- Voie Libre 108 Jan-Mar 2022 SDocumento88 pagineVoie Libre 108 Jan-Mar 2022 SS Bruff100% (2)

- D&E MINIATURES 2000 Model Submarine CatalogDocumento26 pagineD&E MINIATURES 2000 Model Submarine CatalogDUNCAN0420100% (1)

- The Hook and EyeDocumento171 pagineThe Hook and EyebuchkasperNessuna valutazione finora

- VIC 32 EbookDocumento69 pagineVIC 32 Ebook19test77Nessuna valutazione finora

- 132 Hannover CL - II + Pheon Decals. Finished! - Work in ProgDocumento26 pagine132 Hannover CL - II + Pheon Decals. Finished! - Work in Proghscottarmstrong3302Nessuna valutazione finora

- 04AeroModeller April 1958Documento59 pagine04AeroModeller April 1958António OliveiraNessuna valutazione finora

- Flyingscalemodels 202201Documento68 pagineFlyingscalemodels 202201Martijn HinfelaarNessuna valutazione finora

- March 08 Logging Town 25 North Part 2Documento2 pagineMarch 08 Logging Town 25 North Part 2api-190819948Nessuna valutazione finora

- Windsock Datafile Specials - Aircraft of WWIDocumento1 paginaWindsock Datafile Specials - Aircraft of WWISean Campbell100% (1)

- Vermeer BooksDocumento5 pagineVermeer Booksmanu-arrbNessuna valutazione finora

- Website English PDFDocumento6 pagineWebsite English PDFmanu-arrbNessuna valutazione finora

- Turner BibliographyDocumento7 pagineTurner Bibliographymanu-arrbNessuna valutazione finora

- Deirdre Le Faye - Jane Austen The World of Her NovelsDocumento324 pagineDeirdre Le Faye - Jane Austen The World of Her Novelsmanu-arrb100% (7)

- BALPURE - Ballast Water FilterDocumento2 pagineBALPURE - Ballast Water FilterFarihna JoseNessuna valutazione finora

- First Voyage Around The World by Antonio PigafettaDocumento1 paginaFirst Voyage Around The World by Antonio PigafettaJenny OponNessuna valutazione finora

- SAR Seamanship Reference ManualDocumento38 pagineSAR Seamanship Reference Manualkylden100% (2)

- Vessel InformationDocumento241 pagineVessel InformationNayem PoshariNessuna valutazione finora

- Terms and DefinitionsDocumento4 pagineTerms and DefinitionsMitanshu ChadhaNessuna valutazione finora

- Port Development: Port Policy and Trend of Maritime Logistics 2.1.1 Port Policy DirectionDocumento268 paginePort Development: Port Policy and Trend of Maritime Logistics 2.1.1 Port Policy Directionrk100% (1)

- LNT80 - 80,000m LNG Carrier: Main Dimensions Machinery & PropulsionDocumento2 pagineLNT80 - 80,000m LNG Carrier: Main Dimensions Machinery & PropulsionccelesteNessuna valutazione finora

- Deck Opt C15Documento15 pagineDeck Opt C15rheaangelasinutoNessuna valutazione finora

- M2016-S1 Power Failures Safety Study PDFDocumento52 pagineM2016-S1 Power Failures Safety Study PDFSandipan DNessuna valutazione finora

- MC 01-01-2002Documento2 pagineMC 01-01-2002Uhjafwnuijhnfa KmerkgoeNessuna valutazione finora

- SCF Anadyr Intertankocharteringquestionnaire88 Oil PDFDocumento11 pagineSCF Anadyr Intertankocharteringquestionnaire88 Oil PDFPraphon Vanaphitak0% (1)

- Akashia and Hamanasu: Two New Fast-Ferries For ShinnihonkaiDocumento2 pagineAkashia and Hamanasu: Two New Fast-Ferries For ShinnihonkaiEhab Gamal Eldin BarakatNessuna valutazione finora

- SI Vetting GuidelinesDocumento8 pagineSI Vetting GuidelineshsaioudNessuna valutazione finora

- Plane Coordinate Projection Tables Maryland: Department CommerceDocumento17 paginePlane Coordinate Projection Tables Maryland: Department Commercepogopogo22Nessuna valutazione finora

- Naval Arch Written QuestionsDocumento47 pagineNaval Arch Written QuestionsOjasv50% (2)

- PP No. 61 Tahun 2009 (Kepelabuhan) English VersionDocumento54 paginePP No. 61 Tahun 2009 (Kepelabuhan) English VersionSetyaning KartikaNessuna valutazione finora

- H047&H048-CMS-SD-04-12-2 - Cctv-General Position - As Built DrawingDocumento1 paginaH047&H048-CMS-SD-04-12-2 - Cctv-General Position - As Built DrawingDedeNazaludinNessuna valutazione finora

- IRAN - Gas Imports - 20091204Documento5 pagineIRAN - Gas Imports - 20091204Muhammad SiddiuqiNessuna valutazione finora

- Intersection: Plane Coordinate TablesDocumento111 pagineIntersection: Plane Coordinate Tablespogopogo22Nessuna valutazione finora

- Resume - Muhammad Ramdhan SuwandiDocumento3 pagineResume - Muhammad Ramdhan SuwandiramdanNessuna valutazione finora

- Case The Mineral DampierDocumento13 pagineCase The Mineral DampierManamohanNessuna valutazione finora

- Jock McLeanDocumento4 pagineJock McLeanMickThoirsNessuna valutazione finora

- Yacht Design - Interior Design - Naval ArchitectureDocumento15 pagineYacht Design - Interior Design - Naval ArchitectureVirginia MarkovicNessuna valutazione finora

- Application Form - Az-MarinerDocumento5 pagineApplication Form - Az-MarinerŞükürlü KamilNessuna valutazione finora

- Deck Log Book Entries - NavLibDocumento9 pagineDeck Log Book Entries - NavLibLaur MarianNessuna valutazione finora

- Air Bag Launching SystemsDocumento7 pagineAir Bag Launching SystemsJhon GreigNessuna valutazione finora

- Project of Sea Models of TransportDocumento8 pagineProject of Sea Models of TransportАполлінарія МальованаNessuna valutazione finora

- Narrative TextDocumento2 pagineNarrative TextAgungriski AnaNessuna valutazione finora

- Boat Driving Licence Practical Logbook: Transport For NSWDocumento20 pagineBoat Driving Licence Practical Logbook: Transport For NSWWilliam_BitterNessuna valutazione finora

- Maritime SAR Plan PDFDocumento85 pagineMaritime SAR Plan PDFTarek KaaberNessuna valutazione finora