Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Paleopathology and Paleomedicine: An Introduction.

Caricato da

VALIDATE066Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Paleopathology and Paleomedicine: An Introduction.

Caricato da

VALIDATE066Copyright:

Formati disponibili

1 Paleopathology and Paleomedicine

INTRODUCTION

One of our most appealing and persistent myths is that of the Golden Age, a time before the

discovery of good and evil, when death and dis- ease were unknown. But, scientic

evidencemeager, fragmentary, and tantalizing though it often isproves that disease is

older than the human race and was not uncommon among other species. Indeed, stud- ies

of ancient fossil remains, skeletons in museum collections, animals in zoos, and animals in

the wild demonstrate that arthritis is widespread among a variety of medium and large-sized

mammals, including aardvarks, anteaters, bears, and gazelles. Evidence of infection has been

found in the bones of prehistoric animals, and in the soft tissues of mummies. Modern

diagnostic imaging techniques have revealed evidence of tumors in fossilized remains. For

example, researchers performing CT-scans of the brain case of a 72-million-year-old gorgo-

saurus discovered a brain tumor that probably impaired its balance and mobility. Other

abnormalities in the specimen suggested that it had suffered fractures of a thigh, lower leg,

and shoulder. Thus, understanding the pattern of disease and injury that aficted our

earliest ancestors requires the perspective of the paleopathologist. Sir Marc Armand Ruffer

(18591917), one of the founders of paleopathol- ogy, dened it as the science of the

diseases that can be demonstrated in human and animal remains of ancient times.

Paleopathology provides information about health, disease, death, environment, and culture

in ancient populations. In order to explore the problem of disease among the earliest

humans, we will need to survey some aspects of human evolution, both biological and

cultural. In Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871) Charles Darwin argued

that human beings, like every other species, evolved from previous forms of life by means of

natural se- lection. According to Darwin, all the available evidence indicated that man is

descended from a hairy, tailed, quadruped, probably arboreal in its habits. Despite the

paucity of the evidence available to him, Darwin suggested that the ancient ancestor of

modern human beings was related to that of the gorilla and the chimpanzee. Moreover, he

predicted that the rst humans probably evolved in Africa. Evidence from the study of

fossils, stratigraphy, and molecular biology suggests that the separation of the human line

from that of the apes took place in Africa about ve million to eight millionyears ago. The

fossilized remains of human ancestors provide valuable clues to the past, but such fossils are

very rare and usually incomplete. South African anatomist Raymond Dart made the rst

substantive discovery of human ancestors in Africa in the 1920s when he identied the

famous fossils known as Australopithecus africanus (South African Ape-man). The most

exciting subsequent twentieth-century discoveries of ancient humanancestorsare

associatedwiththe workofLouis andMaryLeakey and that of Donald Johanson. Working

primarily at sites in Olduvai Gorge and Laetoli in Tanzania, Mary and Louis Leakey identied

many hominid fossils, including Australopithecus boisei and Homo habilis. Johansons most

important discovery was the unusually complete skeleton of a primitive australopithecine

(Australopithecus afarensis), commonly referred to as Lucy. New hominid remains

discovered at the beginning of the twenty-rst century stimulated further controversy about

the earliest hominid ancestors, as well as those of the chimpanzee. Paleoanthropology is a

eld in which new discoveries inevitably result in the re-examination of previous ndings

and great debates rage over the identication and classication of tiny bits of bones and

teeth. Further discoveries will no doubt add new insights into the history of human evolution

and create new disputes among paleoanthropologists. Scientists also acknowledge that

pseudopaleopathologic conditions can lead to misunderstanding and misinterpretation

because they closely resemble disease lesions, but are primarily the result of postmortem

pro- cesses. For example,because the primary chemical saltsin bones are quite

solubleinwater,soilconditionsthatareconducivetoleachingoutcalcium

cancausechangesinboneslikethoseassociatedwithosteoporosis.Despite

alltheambiguitiesassociatedwithancientremains,manytraumaticevents and diseases can be

revealed by the methods of paleopathology. Insights from many different disciplines,

including archeology, his- torical

geography,morphology,comparativeanatomy,taxonomy,genet- ics, and molecular biology

have enriched our understanding of human evolution. Changes in DNA, the archive of

human genealogy, have been used to construct tentative family trees, lineages, and possible

patterns of early migrations. Some genes may reveal critical distinctions between humans

and other primates, such as the capacity for spoken language. Anatomically modern humans

rst emerged some 130,000 years ago, but fully modern humans, capable of sophisticated

activities, such as the production of complex tools, works of art, and long distancetrade,

seem to appear in the archaeological record about 50,000 years ago. However, the

relationship between modern humans and extinct hominid lines remains controversial. The

Paleolithic Era, or Old Stone Age, when the most important steps in cultural evolution

occurred, coincides with the geological epoch known as the Pleistocene or Great Ice Age,

which ended about 10,000 years ago with the last retreat of the glaciers. Early humans were

hunter-gatherers, that is, opportunistic omnivores who learned to make tools, build shelters,

carry and share food, and create uniquely human social structures. Although Paleolithic

technology is characterized by the manufacture of crude tools made of bone and chipped

stones and the absence of pottery and metal objects, the people of this era produced the

dramatic cave paintings at Lascaux, France, and Altamira, Spain. Presumably, they also

produced useful inventions that were fully bio- degradable and, therefore, left no traces in

the fossil record. Indeed, during the 1960s feminist scientists challenged prevailing

assumptions about the importance of hunting as a source of food among hunter- gatherers.

The wild grains, fruits, nuts, vegetables, and small animals gathered by women probably

constituted the more reliable components of the Paleolithic diet. Moreover, because women

were often encum- bered by helpless infants, they probably invented disposable digging

sticks and bags in which to carry and store food. The transition to a newpattern of food

production through farming and animal husbandry is known as the Neolithic Revolution.

Neolithic or New Stone Age peoples developed crafts, such as basket-making, pot- tery,

spinning, and weaving. Although no art work of this period seems as spectacular as the

Paleolithic cave paintings in France and Spain, Neolithic people produced interesting

sculptures, gurines, and pottery. While archeologists and anthropologists were once

obsessed with the when and where of the emergence of an agricultural way of life, they are

now more concerned with the how and why. Nineteenth-century anthropologists tended to

classify human cultures into a series of ascending, progressive stages marked by the types of

tools manufac- tured and the means of food production. Since the 1960s new analytical

techniques have made it possible to test hypotheses about environmen- tal and climatic

change and their probable effect on the availability of food sources. When the idea of

progress is subjected to critical analysis rather than accepted as inevitable, the causes of the

Neolithic trans- formation are not as clear as previously assumed. Given the fact that hunter-

gatherers may enjoy a better diet and more leisure than agricul- turalists, prehistoric or

modern, the advantages of a settled way of life are obvious only to those who are already

happily settled and well fed. The food supply available to hunter-gatherers, while more

varied than the monotonous staples of the agriculturalist, might well be precarious and

uncertain. Recentstudiesoftheoriginsofagriculturesuggestthatitwasalmost universally

adopted between ten thousand and two thousand years ago, primarily in response to

pressures generated by the growth of the human population. When comparing the health of

foragers and settled farmers, paleopathologists generally nd that dependence on a specic

crop resulted in populations that were less well nourished than hunter- gatherers, as

indicated by height, robustness, dental conditions, and so forth. In agricultural societies, the

food base became narrower with dependence on a few or even a single crop. Thus, the food

supply might have been adequate and consistent in terms of calories, but decient in

vitamins and minerals. Domestication of animals, however, seemed to improve the

nutritional status of ancient populations. Although the total human population apparently

grew very slowly prior to the adoption of farming, it increased quite rapidly thereafter.

Prolonged breast feeding along with postpartum sexual prohibitions found among many

nomadic societies may have maintained long intervals between births. Village life led to

early weaning and shorter birth intervals. The revolutionary changes in physical and social

environment associated with the transition from the way of life experienced by small mobile

bands of hunter-gatherers to that of sedentary, relatively dense populations also allowed

major shifts in patterns of disease. Permanent dwellings, gardens, and elds provide

convenient niches for parasites, insects, and rodents. Stored foods are likely to spoil, attract

pests, and become contaminated with rodent excrement, insects, bacteria, molds, and

toxins. Agricultural practices increase the number of calories that can be produced per unit

of land, but a diet that overemphasizes grains and cereals may be decient in proteins,

vitamins, and minerals. Lacking the mobility and diversity of resources enjoyed by hunters

and gatherers, sedentary populations may be devastated by crop fail- ures, starvation, and

malnutrition. Migrations and invasions of neigh- boring or distant settlements triggered by

local famines may carry parasites and pathogens to new territories and populations.

Ironically, worrying about our allegedly unnatural and articial modern diet has become so

fashionable that people in the wealthiest nations have toyed with the quixotic idea of

adopting the dietary patterns of ancient humans or even wild primates. In reality, the food

supply available to prehistoric peoples was more likely to be inadequate, monotonous,

coarse, and unclean.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Piano Chords PracticeDocumento30 paginePiano Chords PracticeEd Vince89% (9)

- The Poet's Companion - A Guide To The Pleasures of Writing Poetry - GPGDocumento283 pagineThe Poet's Companion - A Guide To The Pleasures of Writing Poetry - GPGChidranveshi100% (1)

- Shorthand TheoryDocumento75 pagineShorthand Theorysubhashcb100% (3)

- We Are All AfricanDocumento5 pagineWe Are All AfricanMaajid BashirNessuna valutazione finora

- Forbidden ArcheologyDocumento17 pagineForbidden ArcheologyAnonymous 1HFV185Sl4Nessuna valutazione finora

- Jared Diamond - The Worst Mistake in The History of The Human RaceDocumento9 pagineJared Diamond - The Worst Mistake in The History of The Human RaceOakymac100% (20)

- Top Ten Nutrients That Support Fat Loss - Poliquin ArticleDocumento4 pagineTop Ten Nutrients That Support Fat Loss - Poliquin Articledjoiner45Nessuna valutazione finora

- Paleolithic PeriodDocumento6 paginePaleolithic Periodlowell delima100% (2)

- Deepa CVDocumento3 pagineDeepa CVDeepa M PNessuna valutazione finora

- The Worst Mistake in The History of The Human Race - by Jared DiamondDocumento4 pagineThe Worst Mistake in The History of The Human Race - by Jared DiamondwhychooseoneNessuna valutazione finora

- CvaDocumento20 pagineCvanuraNessuna valutazione finora

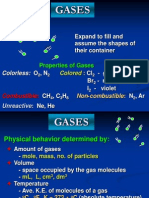

- Properties and Behavior of GasesDocumento34 pagineProperties and Behavior of GasesPaul Jeremiah Serrano NarvaezNessuna valutazione finora

- The Human Origin and Capacity For CultureDocumento54 pagineThe Human Origin and Capacity For CultureJiwon Park100% (1)

- Record of Appropriations and Obligations: TotalDocumento1 paginaRecord of Appropriations and Obligations: TotaljomarNessuna valutazione finora

- Evolution: PaleontologyDocumento50 pagineEvolution: PaleontologySyed Adnan Hussain ZaidiNessuna valutazione finora

- VFTO DocumentationDocumento119 pagineVFTO DocumentationSheri Abhishek ReddyNessuna valutazione finora

- Ant 101: Introduction To Anthropology: Lecture 16: Human EvolutionDocumento27 pagineAnt 101: Introduction To Anthropology: Lecture 16: Human EvolutionAmina MatinNessuna valutazione finora

- Interpreting Archaeology: What Archaeological Discoveries Reveal about the PastDa EverandInterpreting Archaeology: What Archaeological Discoveries Reveal about the PastValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Human EvolutionDocumento10 pagineHuman EvolutionVenn Bacus Rabadon0% (1)

- Chapter 1 Section 1&2 The Frist HumansDocumento25 pagineChapter 1 Section 1&2 The Frist HumansIslam BourbalaNessuna valutazione finora

- Articles From General Knowledge Today: Introduction To PrehistoryDocumento3 pagineArticles From General Knowledge Today: Introduction To PrehistorySunder Singh BishtNessuna valutazione finora

- History of EuropeDocumento200 pagineHistory of EuropeAdedolapo AjayiNessuna valutazione finora

- UNIT 1the First Civilizations and EmpiresDocumento6 pagineUNIT 1the First Civilizations and Empiresspencer agbayaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Gehu 209 - Paleolithic Age & Human Evolution (Notes 1) (1) 2Documento36 pagineGehu 209 - Paleolithic Age & Human Evolution (Notes 1) (1) 2Sugra AlioğluNessuna valutazione finora

- Homo Sapiens: Human Evolution, The Process by WhichDocumento4 pagineHomo Sapiens: Human Evolution, The Process by WhichAndrewNessuna valutazione finora

- 2014 David Pratt Human Origins - The Ape - Ancestry MythDocumento96 pagine2014 David Pratt Human Origins - The Ape - Ancestry MythPelasgosNessuna valutazione finora

- Paleopathology: The Study of Disease in Prehistoric TimesDocumento50 paginePaleopathology: The Study of Disease in Prehistoric TimesrwehjgrebgNessuna valutazione finora

- Human Migration and Settlement PowerpointDocumento14 pagineHuman Migration and Settlement Powerpointapi-287318507Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ancient WK 1 Neolithic SumerDocumento12 pagineAncient WK 1 Neolithic SumerRebecca Currence100% (2)

- Implications For The WorldDocumento18 pagineImplications For The WorldMukesh KaliramanNessuna valutazione finora

- Lifeways of Archaic Homo PopulationDocumento6 pagineLifeways of Archaic Homo PopulationVirendra MathurNessuna valutazione finora

- Escholarship UC Item 3zc4c7cjDocumento16 pagineEscholarship UC Item 3zc4c7cjJosé M Tavares ParreiraNessuna valutazione finora

- Francis Terkula JuniorDocumento11 pagineFrancis Terkula JuniorBala Makoji InnocentNessuna valutazione finora

- The Worst Mistake in The History of The Human Race HE 2Documento6 pagineThe Worst Mistake in The History of The Human Race HE 2Keith Neal100% (1)

- Assignment 1 - Engineering of Living OrganismsDocumento2 pagineAssignment 1 - Engineering of Living OrganismsAshwin VijayakumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Final BookDocumento1.891 pagineFinal Bookimi industries incNessuna valutazione finora

- Human EvolutionDocumento3 pagineHuman EvolutionLira Serrano AgagNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is Big HistoryDocumento6 pagineWhat Is Big HistoryVu Khanh LeNessuna valutazione finora

- 1265 Humanity On The RecordDocumento9 pagine1265 Humanity On The Recordapi-235553158Nessuna valutazione finora

- Was Seafood Brain FoodDocumento4 pagineWas Seafood Brain FoodBrookNessuna valutazione finora

- MODULE 1 The Development of Human PopulationDocumento7 pagineMODULE 1 The Development of Human PopulationGeorgia Alexandria SerraNessuna valutazione finora

- Human Biocultural and Social Evolution: (From Homo Habilis To Homo Sapiens)Documento10 pagineHuman Biocultural and Social Evolution: (From Homo Habilis To Homo Sapiens)Philipjommel MilanoNessuna valutazione finora

- Sts Summary Group 3Documento4 pagineSts Summary Group 3Jem GonzaloNessuna valutazione finora

- Bati Medeniyetleri 1Documento15 pagineBati Medeniyetleri 1JEANZZ AMV'sNessuna valutazione finora

- 0205803504Documento39 pagine0205803504Aarti PalNessuna valutazione finora

- Evolution Documentary Critical AnalysisDocumento2 pagineEvolution Documentary Critical AnalysisRhea CelzoNessuna valutazione finora

- World HistoryDocumento20 pagineWorld HistoryMythics YuccaNessuna valutazione finora

- World HistoryDocumento13 pagineWorld Historymehak khanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Origins and Evolution of Humans in AfricaDocumento4 pagineThe Origins and Evolution of Humans in AfricaAmit KhatriNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 1: The Earliest Beginnings: The Nature of HistoryDocumento5 pagineChapter 1: The Earliest Beginnings: The Nature of HistoryHimana Abdul MalikNessuna valutazione finora

- Isaac1978 - Protohuman HominidsDocumento16 pagineIsaac1978 - Protohuman HominidsdekonstrukcijaNessuna valutazione finora

- General Knowledge TodayDocumento3 pagineGeneral Knowledge Todayjaykar56Nessuna valutazione finora

- Biological Evolution of ManDocumento6 pagineBiological Evolution of ManIvy SarmientoNessuna valutazione finora

- Human Biocultural and Social EvolutionDocumento19 pagineHuman Biocultural and Social EvolutionDebora Chantengco-VirayNessuna valutazione finora

- Ancient Medievial SocietyDocumento407 pagineAncient Medievial SocietyatrijoshiNessuna valutazione finora

- Class - Arch. Anthropology Book Page No. 9, 77, 98, 99 and 109.Documento5 pagineClass - Arch. Anthropology Book Page No. 9, 77, 98, 99 and 109.NUNGSHILONGNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 1: Early HominidsDocumento33 pagineChapter 1: Early HominidsSteven MagidenkoNessuna valutazione finora

- Breaking and Shaping Beastly Bodies: Animals as Material Culture in the Middle AgesDa EverandBreaking and Shaping Beastly Bodies: Animals as Material Culture in the Middle AgesNessuna valutazione finora

- Amsco Book CH 1-StudentDocumento12 pagineAmsco Book CH 1-StudentKimberlyNessuna valutazione finora

- Social and Biological Evolution in the PleistoceneDocumento6 pagineSocial and Biological Evolution in the PleistoceneIshani MukherjeeNessuna valutazione finora

- Prehistory of The PhilippinesDocumento9 paginePrehistory of The PhilippinesJldv VillarinNessuna valutazione finora

- GRE Practice Test 2Documento3 pagineGRE Practice Test 2sxvp123452679Nessuna valutazione finora

- CNU College of Nursing document analyzes evolution of early hominidsDocumento5 pagineCNU College of Nursing document analyzes evolution of early hominidsElisha Gine AndalesNessuna valutazione finora

- Assignment - SofoDocumento5 pagineAssignment - SofoshreyaNessuna valutazione finora

- 1987.05.01.- Diamond, J. - The worst mistake in the history of the human raceDocumento11 pagine1987.05.01.- Diamond, J. - The worst mistake in the history of the human raceChepe ChapínNessuna valutazione finora

- Human Evolution: The Development of Humans from Early PrimatesDocumento5 pagineHuman Evolution: The Development of Humans from Early PrimatesKavya SKNessuna valutazione finora

- CavemanDocumento12 pagineCavemanJuan TownsendNessuna valutazione finora

- KnightDocumento75 pagineKnightVALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- Slaying Your Dragons, One by One.Documento1 paginaSlaying Your Dragons, One by One.VALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- Morning GuardDocumento1 paginaMorning GuardVALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- There Is No Hero Without A DragonDocumento1 paginaThere Is No Hero Without A DragonVALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Guard That Watches ItselfDocumento1 paginaThe Guard That Watches ItselfVALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- Woo-Hoo! Kings Win!Documento1 paginaWoo-Hoo! Kings Win!VALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- Trust The King.Documento8 pagineTrust The King.VALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- King in The Mouth of The WolfDocumento4 pagineKing in The Mouth of The WolfVALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Crown Earned and A Crown LostDocumento1 paginaA Crown Earned and A Crown LostVALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- High Cost To Be KingDocumento1 paginaHigh Cost To Be KingVALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- Living With The King and The Devil DinosaurDocumento1 paginaLiving With The King and The Devil DinosaurVALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- Hero (In) KingDocumento1 paginaHero (In) KingVALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- Yeah, and Who's Watching? - All The Kingmakers, Same As HereDocumento1 paginaYeah, and Who's Watching? - All The Kingmakers, Same As HereVALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- Kings Without KingdomsDocumento5 pagineKings Without KingdomsVALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Lonely King Who Lost His FriendsDocumento1 paginaA Lonely King Who Lost His FriendsVALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Killer RabbitDocumento4 pagineThe Killer RabbitVALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- Heavy Is The Head That Wears The Crown.Documento1 paginaHeavy Is The Head That Wears The Crown.VALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cruci-+ Urb(s) + + (Suffix) Cruciurbicula Crŭci - + Urb(s) + + (Suffix)Documento7 pagineCruci-+ Urb(s) + + (Suffix) Cruciurbicula Crŭci - + Urb(s) + + (Suffix)VALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- To Keep One's Horses Inside TheDocumento1 paginaTo Keep One's Horses Inside TheVALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- Curious Cats - in Art and Poetry (Art Ebook)Documento56 pagineCurious Cats - in Art and Poetry (Art Ebook)VALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- Concerning Lucky Rabbit FeetDocumento1 paginaConcerning Lucky Rabbit FeetVALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- Rottweiler Metzgerhund, Meaning Rottweil Butchers' DogsDocumento1 paginaRottweiler Metzgerhund, Meaning Rottweil Butchers' DogsVALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- φοβού τους ΔαναούςDocumento7 pagineφοβού τους ΔαναούςVALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- είμαι η εμού... ο-η ΑΡΧΗΓΟΣ ΤΩΝ ΛΑΓΩΝDocumento1 paginaείμαι η εμού... ο-η ΑΡΧΗΓΟΣ ΤΩΝ ΛΑΓΩΝVALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- WhiteDocumento1 paginaWhiteVALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- Horse Poetry: I. at Least I Still Make Night WishesDocumento5 pagineHorse Poetry: I. at Least I Still Make Night WishesVALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- Nam Leporem Mortis RubeaeDocumento1 paginaNam Leporem Mortis RubeaeVALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- Put A Shock in ''It''Documento1 paginaPut A Shock in ''It''VALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- ROTHASEDocumento1 paginaROTHASEVALIDATE066Nessuna valutazione finora

- Manual Lift Release System: Parts List and DiagramsDocumento4 pagineManual Lift Release System: Parts List and DiagramsPartagon PowNessuna valutazione finora

- Nestle CompanyDocumento5 pagineNestle CompanymehakNessuna valutazione finora

- Gram Negative Rods NonStool Pathogens FlowchartDocumento1 paginaGram Negative Rods NonStool Pathogens FlowchartKeithNessuna valutazione finora

- The Message Development Tool - A Case For Effective Operationalization of Messaging in Social Marketing PracticeDocumento17 pagineThe Message Development Tool - A Case For Effective Operationalization of Messaging in Social Marketing PracticesanjayamalakasenevirathneNessuna valutazione finora

- Useful List of Responsive Navigation and Menu Patterns - UI Patterns - GibbonDocumento16 pagineUseful List of Responsive Navigation and Menu Patterns - UI Patterns - Gibbonevandrix0% (1)

- 1st Activity in ACCA104Documento11 pagine1st Activity in ACCA104John Rey BonitNessuna valutazione finora

- Expository TextsDocumento2 pagineExpository TextsJodi PeitaNessuna valutazione finora

- AmpConectorsExtracto PDFDocumento5 pagineAmpConectorsExtracto PDFAdrian AvilesNessuna valutazione finora

- Submitted By:: Kelsen's Pure Theory of LawDocumento20 pagineSubmitted By:: Kelsen's Pure Theory of Lawjyoti chouhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Pamantasan NG Lungsod NG Maynila - Freshmen AdmissionDocumento6 paginePamantasan NG Lungsod NG Maynila - Freshmen AdmissionPoppy HowellNessuna valutazione finora

- MELCs Briefer On SPJDocumento27 pagineMELCs Briefer On SPJKleyr QuijanoNessuna valutazione finora

- Corporate Social Responsibility International PerspectivesDocumento14 pagineCorporate Social Responsibility International PerspectivesR16094101李宜樺Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lect 5Documento8 pagineLect 5LuaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sample Management Representation Letter Type II SAS 70 AuditDocumento2 pagineSample Management Representation Letter Type II SAS 70 Auditaaldawi0% (1)

- IFU Egg Yolk Tellurite EmulsionDocumento4 pagineIFU Egg Yolk Tellurite EmulsionoktaNessuna valutazione finora

- Galen and The Antonine Plague - Littman (1973)Documento14 pagineGalen and The Antonine Plague - Littman (1973)Jörgen Zackborg100% (1)

- ZetaPlus EXT SP Series CDocumento5 pagineZetaPlus EXT SP Series Cgeorgadam1983Nessuna valutazione finora

- SDH PDFDocumento370 pagineSDH PDFClaudia GafencuNessuna valutazione finora

- Dams of India - 6921143 - 2022 - 08 - 22 - 03 - 48Documento10 pagineDams of India - 6921143 - 2022 - 08 - 22 - 03 - 48deepak kumar pandeyNessuna valutazione finora

- Dada and Buddhist Thought - Sung-Won Ko PDFDocumento24 pagineDada and Buddhist Thought - Sung-Won Ko PDFJuan Manuel Gomez GarcíaNessuna valutazione finora

- Topic 2Documento6 pagineTopic 2Vince Diza SaguidNessuna valutazione finora

- TLC Treatment and Marketing ProposalDocumento19 pagineTLC Treatment and Marketing Proposalbearteddy17193Nessuna valutazione finora