Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Coastal Reclamation Guidelines

Caricato da

Pratama Rizqi AriawanCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Coastal Reclamation Guidelines

Caricato da

Pratama Rizqi AriawanCopyright:

Formati disponibili

ENVIRONMENTAL

GUIDELINES

FOR

RECLAMATION IN

COASTAL AREAS

February 2012

DEP ARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES, ENVI RONMENT, THE ARTS AND SP ORT

- 1 -

CONTENTS

1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... - 2 -

1.1 Why Have Coastal Reclamation Guidelines? ................................ - 2 -

1.2 Planning Requirements ................................................................. - 3 -

1.2.1 Aboriginal land claims and native title claims ................................ - 3 -

1.2.2 Control Plans and Consent Authorities ......................................... - 3 -

1.2.3 Environment and Heritage Planning .............................................. - 4 -

1.2.4 Site Management Planning ........................................................... - 5 -

2 ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT ISSUES............................... - 5 -

2.1 Acid Sulfate Soils .......................................................................... - 5 -

2.1.1 Management techniques ............................................................... - 6 -

2.2 Sediment and Erosion Control ...................................................... - 8 -

2.2.1 Siltation of Waterways ................................................................... - 8 -

2.2.2 Impacts to Coastal hydrodynamics ............................................... - 8 -

2.3 Use of appropriate fill .................................................................... - 9 -

2.4 Removal and disposal of mangroves .......................................... - 10 -

2.5 Fire Management ........................................................................ - 10 -

2.6 Dust Management ....................................................................... - 10 -

2.7 Site security and supervision ...................................................... - 11 -

BIBLIOGRAPHY ....................................................................................... - 12 -

DISCLAIMERThese guidelines provide assistance in the assessment and management of developments

in coastal areas. The guidelines are not exhaustive and while they have been prepared in good faith, exercising all

due care and attention, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to the accuracy,

completeness or fitness for purpose of the guidelines in respect of any users circumstances. Users of the

guidelines should undertake their own investigations and seek appropriate expert advice where necessary in

relation to their particular situation. These guidelines may be updated when new information is made available or

when land reclamation techniques change.

DEP ARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES, ENVI RONMENT, THE ARTS AND SP ORT

- 2 -

1 INTRODUCTION

These guidelines provide practical environmental advice to developers who are planning to

undertake reclamation work in coastal regions of the Northern Territory. The guidelines apply

to activities such as foreshore filling in coastal areas and along rivers, canal estate, marina

and port developments, coastal aquaculture developments and development occurring on

coastal floodplains. In order to minimise environmental impacts it is important to consider

planning requirements before reclamation begins.

1.1 Why Have Coastal Reclamation Guidelines?

The object of the guidelines is to minimise the impacts of reclamation on coastal habitats and

coastal water quality. The main environmental issues associated with land reclamation in

coastal areas include the loss of natural habitat and the subsequent potential reduction in

biodiversity, erosion of the coastline and pollution of the marine environment especially from

acid sulfate soils. Issues related to land reclamation in the coastal zone include those

associated with biting insects and engineering considerations such as subsidence and

corrosion of building foundations.

The Northern Territory coast has extensive areas of mangrove lined estuaries and freshwater

floodplains. Mangrove communities:

sustain the commercial and recreational fishing industry, by acting as nurseries and feed

areas for a wide variety of fish and crustacean species;

provide protection of the shoreline and maintain water quality by stabilising sediments,

preventing erosion and filtering run-off from the land;

offer a range of recreational activities such as boating, fishing, bird watching, wildlife

observation and photography as well as educational opportunities; and

provide the environment for scientific research on the unique adaptations and ecological

systems associated with mangroves.

The NT coastline has some of the most potentially toxic acid sulfate soils recorded in

Australia. The high potential acidity can make treatment and neutralisation of soil material

costly and impractical. Darwin Harbour mangrove muds have been found in some cases to

require one tonne of pure lime to neutralise 1 tonne of mangrove mud.

In other areas of Australia the impact of population growth has had a significant adverse effect

on the coastal zone. The Northern Territory is fortunate that much of the coastal zone is

largely in its natural state. This provides the opportunity to learn from experience and plan for

DEP ARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES, ENVI RONMENT, THE ARTS AND SP ORT

- 3 -

future development to minimise the impact on the natural coastal environment providing for

the expected increase in population and the associated demand for coastal development.

1.2 Planning Requirements

1.2.1 Aboriginal land claims and native title claims

Before any coastal reclamation is undertaken, the status of the area with respect to Aboriginal

land claims and native title claims must be clarified. Even in the absence of a specific native

title claim over an area, there may be native title implications.

If the area is subject to either an Aboriginal land or a native title claim, certain procedures

must be followed before reclamation is undertaken. These procedures will vary according to

the nature of the claim. General guidelines are provided in Table 1. Further information can be

obtained from the Indigenous Land Issues team / Land Administration Division / NT Lands

Group / Department of Lands and Planning.

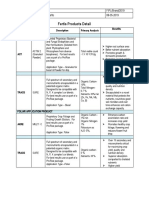

Table 1: Aboriginal Land Claims and Native Title Cl aims

AREA

SUBJECT TO: DEVELOPMENT

PROCEDURES

All land between low water Aboriginal land claim under the

Aboriginal Land Rights (NT) Act.

Land Claims must be resolved

and be finally disposed of before

development can proceed.

Intertidal zone between low

and high water marks in areas

adjacent to pastoral leases

Aboriginal land claim under the

Aboriginal Land Rights (NT) Act.

Land Claims must be resolved

and be finally disposed of before

development can proceed.

Some parts of coast Native title under the Native Title

Act.

According to the Native Title Act

1.2.2 Control Plans and Consent Authorities

The planning requirements for a project depend on the area in which the development is to

occur. All foreshore filling in areas covered by the Darwin Town Plan 1992 (as amended), for

example, requires consent from the Development Consent Authority. All development covered

by the East Arm Control Plan requires Ministerial consent. Development Assessment Services

/ NT Lands Group / Department of Lands and Planning can provide more information

regarding planning requirements.

Other approvals may be required from the Authorities outlined in Table 2.

DEP ARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES, ENVI RONMENT, THE ARTS AND SP ORT

- 4 -

Table 2: Coastal development requiring specific approval by NT Government Authorities

Area or Type of Development Consent Authority

Below high tide in Darwin Harbour Above

low tide in NT Coastal Waters Aquaculture

Mineral or oil and gas exploration Dredging

Operations

Darwin Port Corporation

Marine Safety Branch / Department of Lands and

Planning

Fisheries Group / Department of Resources

Minerals and Energy Group / Department of

Resources

Department of Natural Resources, Environment

the Arts and Sport

1.2.3 Environment and Heritage Planning

A number of environmental and heritage issues must be considered prior to undertaking any

reclamation. Table 3 provides a checklist of these issues and the appropriate procedures for

addressing them.

Table3: Environmental and Heritage issues to be considered in reclamati on developments and

the appropri ate development procedures.

Environmental

Consideration

Development Procedure

Does the development have potentially

significant environmental impacts?

The proposal may be required to undergo formal

assessment under the NT Environmental Assessment Act.

This will be decided by the Minister for Natural Resources,

Environment and Heritage, following consideration of a

Notice of Intent or formal development application.* The

proposal may also require assessment under the

Australian Environment Protection and Biodiversity

Conservation Act, if the proposal has a potential impact on

matters of national environmental significance. The

Australian Department of Sustainability, Environment,

Water, Population and Communities should be contacted

for further information.

Is the development within a National

Park or Conservation Reserve?

Development must be undertaken in accordance with the

provisions of the Territory Parks and Wildlife Act.

Will the development encroach on any

sacred sites?

An Authority Certificate must be sought from the Aboriginal

Areas Protection Authority under the NT Aboriginal Sacred

Sites Act.

Will the development affect any

heritage or archaeological places or

objects?

Heritage Clearances must be sought from the Minister for

Natural Resources, Environment and Heritage through the

Heritage Branch Environment and Heritage Division /

Department of Natural Resources, Environment the Arts

and Sport.

Does the development impact on any

Beneficial Uses?

Potential impacts on water quality will be managed by

issue of a Waste Discharge Licence under the Water Act

1992.

@

* Further information about the environmental assessment process can be found in A Guide to the

Environmental Impact Assessment Process in the NT.

@

Further information on Beneficial Uses can be obtained from the Controller of Water, Natural

Resource Management / Department of Natural Resources, Environment the Arts and Sport. Beneficial

uses have been declared for several coastal areas including Darwin Harbour and are Recreation and

Aesthetics and Aquatic Eco-systems protection.

DEP ARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES, ENVI RONMENT, THE ARTS AND SP ORT

- 5 -

1.2.4 Site Management Planning

Before commencing reclamation activities, an environmental management plan should be

prepared. The plan should consider the purpose of the reclamation, the physical constraints of

the site (such as storm surge, reclamation extent, erosion and siltation) and significant natural

or cultural features. Sulfidic soils should be identified at this stage. Consideration of these

issues during the design stage will have long term environmental and economic benefits,

whereas mitigation of problems after they have arisen is often time consuming and costly.

Development that requires direct access to the sea should be designed to ensure that only the

minimum required amount of reclamation is undertaken. This can be achieved by confining

most site development to above the intertidal zone and retaining as much of the natural

land/sea interface as possible.

Reclamation in coastal areas can affect the local hydrodynamics (water movement) and lead

to erosion or siltation in unexpected areas. Natural Resource Management / Department of

Natural Resources, Environment the Arts and Sport should be contacted early in the planning

stage for advice in this area.

2 ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT ISSUES

The following sections suggest management techniques that can be used to avoid or minimise

potential adverse impacts of reclamation works.

2.1 Acid Sulfate Soils

Sediments that contain iron sulfides and with a potential to oxidize and produce acid following

disturbance are found in low-lying coastal areas, such as mangroves salt marshes, estuaries,

tidal lakes and coastal floodplains. Management and rehabilitation of an area badly affected

by acid leachate will most likely be time consuming and costly, if indeed it is possible. In some

areas of Australia, soils drained 100 years ago are still releasing acid.

Sulfidic Soils

This is the name given to a layer of permanently waterlogged iron sulfide soil. It is given this

name because it has the potential for the iron sulfides to oxidise and produce sulfuric acid. If

left undisturbed the water keeps oxygen away from the iron sulfides and prevents oxidation. In

this waterlogged state the sediment is inert and harmless to the environment. Sulfidic soils are

usually dark grey in colour.

DEP ARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES, ENVI RONMENT, THE ARTS AND SP ORT

- 6 -

Sulfuric Soil

If sulfidic soil is exposed to the air through natural processes, drainage or excavation, the iron

sulfide in the soil react with oxygen in the air and produce sulfuric acid as a by-product. The

resulting soil is then known as acid sulfate soil or soil containing sulfuric horizons. Some of

this acid may be neutralised by other minerals in the soil; however, most of the acid moves

through the soil contaminating the surrounding ground and surface waters.

Potential Environmental impacts of sulfuric acid leachate include:

the release of highly acidic water into the marine or freshwater environment resulting in the

death of fish and other marine organisms;

the reduction of bicarbonates from seawater resulting in potential deformities in shellfish

development;

the release of toxic and heavy metals from the sediment further degrading the marine

environment; and

corrosion of metals and weakening of concrete structures resulting in significant impact on

infrastructure and /or engineering works.

Some indications of acid sulfate soils in the Northern Territory are:

Thick black organic soil layers in coastal floodplains and intertidal areas

Smell of Hydrogen Sulfur (rotten egg gas) when disturbed

Grey gleyed marine muds

2.1.1 Management techniques

Intertidal areas, including mangrove muds, intertidal mud flats and coastal floodplains are

typically sulfidic but sulfuric soils are known to occur. For this reason the acidity is not obvious

until oxidised or exposed to oxygen. Field tests are indicative only and should always be

supported with quantitative Chromium Reducible Sulfur (CRS) testing. CRS results are

essential

for any acid sulfate soil management plan. The results are essential for determining

acid base accounting.

The best management technique for reclamation in tidal areas is to avoid exposing the mud to

the air. Other techniques include re-covering the mud with water immediately after disturbance

and/ or liming to neutralise any sulfuric acid formed (costly for large areas).

Some of the most common methods of land reclamation are:

Filling over the mangroves and mud;

Construction of bunds and filling the resultant ponds with dredged material or clean fill;

and

DEP ARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES, ENVI RONMENT, THE ARTS AND SP ORT

- 7 -

Removing mangroves and mud and placing the fill on the underlying rock/hard substratum

below.

Each method has advantages and disadvantages. The first is possibly the best method with

regard to minimising acid leachate generation; however, subsidence may occur, which may

expose sulfidic soils.

If using the second method and the dredged material contains mangrove mud, it must be kept

covered with water during reclamation to reduce the potential for acid generation. The area

will require long term consolidation, settlement and capping with an impervious layer (e.g.

geotextile or clay) prior to construction taking place. Monitoring of leachate for acid generation

may be required.

The latter method reduces the potential for subsidence but greatly increases the potential for

creating acid leachate from the exposure of mangrove mud to air. If this method of

reclamation is used, mud should not be allowed to dry out. Mangrove mud should not be used

as fill material above 2.5 m AHD and should immediately be covered with clean fill. Where

possible all sulfidic soils should be managed within the footprint of the development. Advice

regarding management options, analytical techniques and potential environmental impacts

can be obtained from Natural Resource Management / Department of Natural Resources,

Environment the Arts and Sport.

During the design stage of the reclamation project the presence of sulfidic soils should be

determine by geotechnical investigation and analytical testing. CRS testing will help to

determine the presence of sulfidic soils. If they are detected, the volume of sulfidic soils that

will be disturbed during the reclamation and the soils neutralising capacity should also be

determined. It is recommended that soils be analysed according to the quantitative Chromium

Reducible Sulfur (CRS) testing methods according to Soil Chemical Methods - Australasia

(Rayment and Lyons, 2011).

Acid sulfate soil management will need to be incorporated into the environmental

management plan if sulfidic or sulphuric soils are detected. The plan should include methods

of reclamation, acid sulfate soil management, including neutralisation, transport, storage and

a monitoring regime that will allow for the early detection of acidic leachates. More detailed

information regarding the analysis and management of sulfidic soils can be found in state acid

sulfate soil assessment, management and monitoring guidelines published by Queensland,

New South Wales and Western Australia

DEP ARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES, ENVI RONMENT, THE ARTS AND SP ORT

- 8 -

Key Points

The following practices will assist management of acid sulfate soils:

include acid sulfate soil management in the environmental management plan;

avoid extraction of mangrove mud where possible;

if mud is disturbed, cover as soon as possible with water or clean fill;

when filling over mangrove mud, cap the reclaimed area with an impervious layer such as

clay; and

monitor reclamation activities for signs of acid generation.

2.2 Sediment and Erosion Control

Protection of fresh and marine water quality in the surrounding environment is one of the

major concerns when reclaiming land in coastal areas. As indicated earlier, Beneficial Uses

under the NT Water Act have been declared for several coastal areas in the Northern

Territory.

2.2.1 Siltation of Waterways

Water quality may be affected by erosion. Siltation of waterways can occur as a direct result of

erosion of soil from the reclamation site. Stormwater should not be allowed to run through the

reclamation site into nearby waterways and the sea without appropriate silt and erosion

control measures being in place. There are several methods that can be used to manage the

movement of water through reclamation sites. These include silt traps, retention of vegetation

(buffer strips, grass) and construction of diversion walls or drains on the upstream side of the

site to divert surface runoff towards appropriately controlled discharge points. Confining

reclamation construction activities to the dry season will minimise problems associated with

stormwater runoff.

If it is necessary to reclaim land adjacent to the sea where the face of the reclamation site is

subject to tidal inundation, methods to stop inundation (while managing sulfidic soils) such as

a bund wall may be needed. Bund walls should be engineered to an appropriate design

(depending on the construction material) and stabilised using techniques such as rock

armoury and geotextile material.

2.2.2 Impacts to Coastal hydrodynamics

In addition, construction activities associated with reclamation may cause indirect siltation and

sediment movement. For example, wharves and breakwaters can affect the hydrodynamics of

the marine environment which may lead to erosion of adjacent foreshores and siltation of

waterways. Excessive siltation may impact on local marine life (mangroves, molluscs, fish).

DEP ARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES, ENVI RONMENT, THE ARTS AND SP ORT

- 9 -

The best way to minimise changes to hydrodynamics of an area is to retain the existing

natural environment at the land/sea interface. It is recommended that, wherever possible, the

natural vegetation is retained to assist foreshore stabilisation. Some areas may benefit by

recolonisation of mangroves in previously disturbed areas.

For further information on erosion and appropriate site drainage as well as hydrodynamics

contact Natural Resource Management / Department of Natural Resources, Environment the

Arts and Sport.

2.3 Use of appropriate fill

Sulfuric acid is only one kind of leachate that may be generated by poor reclamation practices.

Other harmful leachates can be produced when water comes into contact with contaminated

fill materials. This is most commonly caused by infiltration of stormwater into the fill material

and/ or percolation of seawater into an exposed reclamation face. This problem can worsen

when combined with acid leachate generation. The acid leachate may provide ideal conditions

for the mobilisation of contaminants such as iron, aluminium and heavy metals including

cadmium, copper, lead and chromium which are highly toxic to fish and other marine life.

Contaminated fill material, especially household rubbish, can also pose serious health risks.

Persistent pathogenic micro-organisms such as Salmonella bacteria are readily transferred by

pests to food, humans or previously uncontaminated insect and animal populations.

Examples of material unsuitable for fill are as follows:

liquid waste including sludge, sewage and grease trap waste;

any material scheduled as a dangerous good under the provisions of the NT Dangerous

Goods Act (contact the Work Health Authority for advice);

pesticides and pesticide containers;

hazardous wastes including asbestos, radioactive material and medical wastes;

household and commercial garbage, putrescibles (eg. Plastics, cardboard/paper, kitchen

wastes, carcasses);

timber, corrugated iron and other metals;

vegetation (depending on the purpose of the reclamation);

oil drums and plastic containers;

gas bottles;

car bodies and other discarded household items such as white goods; and

tyres.

DEP ARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES, ENVI RONMENT, THE ARTS AND SP ORT

- 10 -

Some thought should be given to securing the reclamation site to prevent unauthorized

dumping. If any material is found to be the cause of pollution action may be taken under the

Water Act and/or the Waste Management and Pollution Control Act.

Reclamation materials must be solid, inert and non-hazardous. Materials may include

uncontaminated soil, rocks and building demolition rubble such as bricks and concrete. Steel

and timber ultimately break down and are therefore not considered suitable fill materials.

Construction methods may also involve filling bunded areas with uncontaminated dredged

material. This may be suitable for areas that will be allowed to settle for some time or have

other accelerated consolidation efforts applied. The use of dredged material in land

reclamation should be incorporated into the environmental management plan especially if the

dredged material contains sulfidic soils (see previous section).

2.4 Removal and disposal of mangroves

At some reclamation sites, mangroves have been left in place and covered with fill material.

Geotechnical advice should be sought to ensure land stability in the event that mangrove and

other vegetation is not removed and covered with fill material. If removal of mangroves is

necessary mangrove vegetation should not be stockpiled at the reclamation site because it

can create breeding habitats for biting insects. Options for mangroves and/ or vegetation that

are not salvaged include mulching, burning on site (in accordance with the requirements of the

NT Police, Fire and Emergency Services or Bushfires NT) or taken to the local waste disposal

site with the approval of the local council.

2.5 Fire Management

Burning of waste can be a significant environmental hazard which has pollution, safety and

nuisance implications. Burning-off is not permitted anywhere within a 130 km radius from the

Darwin CBD without a permit from the NT Police, Fire and Emergency Services or the

Bushfires NT.

Legislation provides that the NT Police, Fire and Emergency Services must be informed if any

fires start anywhere within the Darwin Emergency Response Area (ERA) which encompasses

all coastal regions between the mouths of Howard River around to the Elizabeth River.

Outside this ERA the Bushfires NT need only be informed when a fire threatens life or

property.

2.6 Dust Management

Dust management is an important environmental and public health issue on development

sites during the dry season. The generation of dust is dependent on the soil/geological

DEP ARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES, ENVI RONMENT, THE ARTS AND SP ORT

- 11 -

conditions and on the local weather conditions. In accordance with the Public Health Act and

Waste Management and Pollution Control Act dust must be suppressed so as not to create a

nuisance. This can be achieved by:

minimising vegetation clearance;

revegetating areas that are no longer required for reclamation or construction;

ensuring that unsealed roads and exposed areas are watered at all times;

applying speed restrictions; and

ensuring reclamation and construction activities take into consideration the local wind

conditions.

2.7 Site security and supervision

The acceptance and placement of reclamation materials should be supervised to prevent

unauthorised dumping of wastes and unsuitable fill material. Unauthorised dumping may

result in double handling of materials and the payment of disposal costs if the materials need

to be removed. In addition, foreshore lands are generally highly visible and poor management

may lead to public complaints and regulatory action under the Water Act and/or the Waste

Management and Pollution Control Act.

DEP ARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES, ENVI RONMENT, THE ARTS AND SP ORT

- 12 -

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brocklehurst, P. and Edmeades, B. (1996) The Mangrove Communities of Darwin Harbour.

Technical Memorandum No. 96/9. Department of Lands, Planning and

Environment. Darwin.

NRETAS (2012) A guide to the Environmental Impact Assessment Process in the Northern

Territory. Environmental Assessment Unit / Environment and Heritage Division

/ Department of Natural Resources, Environment, the Arts and Sport. Accessed

9 Feb 2012 from:

www.nretas.nt.gov.au/environment-protection/assessment/eiaguide .

Hadden K. (1993) Soil Conservation Handbook for Parks and Reserves in the NT. Natural

Resources Division, Department of Lands, Planning and Environment

Northern Territory Department of Lands and Housing (1990) Darwin Regional Land Use

Structure Plan. Northern Territory Department of Lands and Housing. Darwin.

Accessed 9 Feb 2012 from:

http://www.nt.gov.au/lands/planning/scheme/documents/darwinregion-

lusp1990.pdf

Rayment, GE. and Lyons, DJ . (2011). Soil and Chemical Methods - Australasia. CSIRO

Publishing, Melbourne

Sammut, J . (1997). An Introduction to Acid Sulfate Soils. Acid Sulfate Soils Management

Advisory Committee, Australia.

Whelan, P.I. (2011) Guidelines for Preventing Mosquito with Construction Practice near

Tidal Areas in the NT. Medical Entomology / Centre for Disease Control /

Northern Territory Department of Health. Darwin NT. J une 1988.

Updated February 2011. Accessed 9 Feb 2012 from:

http://www.health.nt.gov.au/library/scripts/objectifyMedia.aspx?file=pdf/3

2/37.pdf&siteID=1&str_title=Construction practice near tidal areas -

guidelines to prevent mosquito breeding.pdf

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Management of Marine Protected Areas: A Network PerspectiveDa EverandManagement of Marine Protected Areas: A Network PerspectivePaul D. GoriupNessuna valutazione finora

- The Gulf of Guinea Large Marine Ecosystem: Environmental Forcing and Sustainable Development of Marine ResourcesDa EverandThe Gulf of Guinea Large Marine Ecosystem: Environmental Forcing and Sustainable Development of Marine ResourcesNessuna valutazione finora

- Pacific Northwest LNG Project: Environmental Assessment ReportDocumento339 paginePacific Northwest LNG Project: Environmental Assessment ReportArdhi TaNessuna valutazione finora

- Oil Blowout Contingency Planning and CountermeasuresDocumento6 pagineOil Blowout Contingency Planning and Countermeasuresdaburto2Nessuna valutazione finora

- Eia Assignment No 5Documento10 pagineEia Assignment No 5Swati GuptaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lupin Fras TissuesDocumento38 pagineLupin Fras TissuesMalou SanNessuna valutazione finora

- Villaflor, Jesus Jr. O 2019-30506Documento5 pagineVillaflor, Jesus Jr. O 2019-30506Jesus Villaflor Jr.Nessuna valutazione finora

- EIA Procedure and Requirements in MalaysiaDocumento56 pagineEIA Procedure and Requirements in Malaysiasarah adrianaNessuna valutazione finora

- CRZ Port Blair FortuneDocumento19 pagineCRZ Port Blair FortuneNEFSYA KAMALNessuna valutazione finora

- Alternative Shoreline Management GuidebookDocumento28 pagineAlternative Shoreline Management GuidebookHRNERRNessuna valutazione finora

- Cayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 2.M.6 Marine Habitats Artificial InstallationsDocumento4 pagineCayman Islands National Biodiversity Action Plan 2009 2.M.6 Marine Habitats Artificial Installationssnaip1370Nessuna valutazione finora

- Environment Management in The Oil-Rich Albertine GrabenDocumento30 pagineEnvironment Management in The Oil-Rich Albertine GrabenAfrican Centre for Media ExcellenceNessuna valutazione finora

- Aquaculture Planning Guidance Nov 2016Documento54 pagineAquaculture Planning Guidance Nov 2016malekaliNessuna valutazione finora

- R R R Roooocccck K K Ky y y y Sssshhhhoooorrrreeee H H H Ha Aa Abbbbiiiittttaaaatttt Aaaaccccttttiiiioooon N N N Ppppllllaaaan N N NDocumento5 pagineR R R Roooocccck K K Ky y y y Sssshhhhoooorrrreeee H H H Ha Aa Abbbbiiiittttaaaatttt Aaaaccccttttiiiioooon N N N Ppppllllaaaan N N NalidaeiNessuna valutazione finora

- Case StudyDocumento7 pagineCase Studyroderick biazonNessuna valutazione finora

- Position Paper Pgoc FinalDocumento6 paginePosition Paper Pgoc FinalJamaica CabanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Coastal Zone MBA DMDocumento4 pagineCoastal Zone MBA DMsaksham111Nessuna valutazione finora

- Coastal Regulation Zone: Why in News?Documento4 pagineCoastal Regulation Zone: Why in News?Roshan NazarethNessuna valutazione finora

- CRZ PDFDocumento11 pagineCRZ PDFharsh15032001Nessuna valutazione finora

- FINAL Salazar Letter 9 3Documento3 pagineFINAL Salazar Letter 9 3Heather M. Handley GoldstoneNessuna valutazione finora

- CHAPTER4 Policy Framework and Action PlansDocumento12 pagineCHAPTER4 Policy Framework and Action PlansJAY CASIBANGNessuna valutazione finora

- Green Infrastructure For The Coast: A Primer For Local Decision MakingDocumento52 pagineGreen Infrastructure For The Coast: A Primer For Local Decision MakingelinzolaNessuna valutazione finora

- 20170201-FINAL EHS+Guidelines+for+Ports+Harbors+and+Terminals PDFDocumento35 pagine20170201-FINAL EHS+Guidelines+for+Ports+Harbors+and+Terminals PDFmarineconsultantNessuna valutazione finora

- 1http://www - Indiancoastguard.nic - in/Indiancoastguard/NOSDCP/Marine Environment Security/pichbook - PDF Ws - Papers/walker - 0506 - Stlucia PDFDocumento3 pagine1http://www - Indiancoastguard.nic - in/Indiancoastguard/NOSDCP/Marine Environment Security/pichbook - PDF Ws - Papers/walker - 0506 - Stlucia PDFKumar NaveenNessuna valutazione finora

- Multiple Objectives, One Marine Planning ProcessDocumento2 pagineMultiple Objectives, One Marine Planning ProcessRia PatelNessuna valutazione finora

- EIA Procedure and Requirements in MalaysiaDocumento56 pagineEIA Procedure and Requirements in MalaysiaWan RidsNessuna valutazione finora

- R02C02-3050 - ER - Civil Works - P02 - South ComDocumento9 pagineR02C02-3050 - ER - Civil Works - P02 - South ComOsama KheadryNessuna valutazione finora

- Guidelines For Marinas and BoatyardsDocumento32 pagineGuidelines For Marinas and BoatyardsNirmala DeshaNessuna valutazione finora

- Proposed Ordinance MangrovesDocumento5 pagineProposed Ordinance Mangrovesjeffrey100% (1)

- Zoning MatriksDocumento18 pagineZoning MatriksLia KusumawatiNessuna valutazione finora

- Coastal Regulation in India: Why Do We Need A New Notification?Documento69 pagineCoastal Regulation in India: Why Do We Need A New Notification?ajaythakur11Nessuna valutazione finora

- Coastal Regulation in India - Why Do We Need A New Notification?Documento68 pagineCoastal Regulation in India - Why Do We Need A New Notification?Equitable Tourism Options (EQUATIONS)Nessuna valutazione finora

- CHAPTER 8 Flood Control/Mitigation and Hazard ManagementDocumento11 pagineCHAPTER 8 Flood Control/Mitigation and Hazard ManagementCeline CervantesNessuna valutazione finora

- Guide Questions:: Enrichment ActivityDocumento5 pagineGuide Questions:: Enrichment ActivityMarjorie VisteNessuna valutazione finora

- 9 Iczm NwaDocumento12 pagine9 Iczm NwaMamtaNessuna valutazione finora

- Legal CC Report - GuyanaDocumento46 pagineLegal CC Report - GuyanaJinky ComonNessuna valutazione finora

- G10 LANDSUBDIVISIONadjacenttoWATERCOURSESDocumento26 pagineG10 LANDSUBDIVISIONadjacenttoWATERCOURSESApriadi Budi RaharjaNessuna valutazione finora

- Land Use Compatibility Tables For Public Drinking Water Source AreasDocumento47 pagineLand Use Compatibility Tables For Public Drinking Water Source AreasEshe2aNessuna valutazione finora

- Cemetery Guidance Northern IrelandDocumento12 pagineCemetery Guidance Northern IrelandKelli FlorianiNessuna valutazione finora

- 2000 EPA Guyana ICZM Action PlanDocumento36 pagine2000 EPA Guyana ICZM Action Planhanoi09Nessuna valutazione finora

- AO 07 of DENRDocumento16 pagineAO 07 of DENRImmediateFalcoNessuna valutazione finora

- Draft Sida Project Proposal Oil and GasDocumento18 pagineDraft Sida Project Proposal Oil and GasnjennsNessuna valutazione finora

- Vulnerability Analysis To Climate Change Along The Caribbean Coasts of Belize, Guatemala and HondurasDocumento90 pagineVulnerability Analysis To Climate Change Along The Caribbean Coasts of Belize, Guatemala and HondurasPrograma Regional para el Manejo de Recursos Acuáticos y Alternativas EconómicasNessuna valutazione finora

- T Proc Notices Notices 035 K Notice Doc 31857 894042755Documento8 pagineT Proc Notices Notices 035 K Notice Doc 31857 894042755abdim1437Nessuna valutazione finora

- Eis TM Terrestrial Ecology Information GuideDocumento16 pagineEis TM Terrestrial Ecology Information Guideowuiedh fewuigNessuna valutazione finora

- Am Is 2024 Marine Protected Area Project ProfileDocumento7 pagineAm Is 2024 Marine Protected Area Project ProfileDebah Diaz Baclayon WaycoNessuna valutazione finora

- Coastal Land - and Sea-Use Zoning Plan of The Province of BataanDocumento104 pagineCoastal Land - and Sea-Use Zoning Plan of The Province of BataanPEMSEA (Partnerships in Environmental Management for the Seas of East Asia)100% (5)

- Costal Zone Policy 2005Documento14 pagineCostal Zone Policy 2005rifat sharkerNessuna valutazione finora

- NCR - Mainstreaming CCA in LPPCHEADocumento13 pagineNCR - Mainstreaming CCA in LPPCHEABienvenido Valerio0% (1)

- Green Shores Project Charter ExampleDocumento12 pagineGreen Shores Project Charter Exampleqkhan2000Nessuna valutazione finora

- Coastal Regulation in India - A Saga of BetrayalDocumento5 pagineCoastal Regulation in India - A Saga of BetrayalEquitable Tourism Options (EQUATIONS)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Handbook of Dredging ActivitiesDocumento57 pagineHandbook of Dredging Activitiesulhas_nakashe0% (1)

- Strategic Action Programme For The Red Sea and Gulf of AdenDocumento111 pagineStrategic Action Programme For The Red Sea and Gulf of Adentsadkans59Nessuna valutazione finora

- Coastal Regulation Zone 2020Documento5 pagineCoastal Regulation Zone 2020maheshdadiNessuna valutazione finora

- Wellhead ProtectionDocumento14 pagineWellhead Protectionhashem aliNessuna valutazione finora

- Report Southern Coalfields Final Jul08Documento168 pagineReport Southern Coalfields Final Jul08Scott DownsNessuna valutazione finora

- Biodiversity Report by Cottonwood Consultants in Opposition To The Badlands Motorsports Resort DevelopmentDocumento30 pagineBiodiversity Report by Cottonwood Consultants in Opposition To The Badlands Motorsports Resort DevelopmentRandall WiebeNessuna valutazione finora

- Dock PierDocumento69 pagineDock Pierباسل ديوبNessuna valutazione finora

- MSI-Slides For IDP Week02Documento41 pagineMSI-Slides For IDP Week02u2103207Nessuna valutazione finora

- Draft Guidelines For Preparation of Brief Document To Facilitate Implementation of The Wetlands (Conservation and ManagementDocumento17 pagineDraft Guidelines For Preparation of Brief Document To Facilitate Implementation of The Wetlands (Conservation and ManagementForest Range Officer ThuraiyurNessuna valutazione finora

- Short Sea Shipping in EuropeDocumento78 pagineShort Sea Shipping in Europepragya89Nessuna valutazione finora

- Coastal Planning of Jakarta Waterfront - Pratama Rizqi Ariawan PDFDocumento5 pagineCoastal Planning of Jakarta Waterfront - Pratama Rizqi Ariawan PDFPratama Rizqi AriawanNessuna valutazione finora

- Port Planning AssignmentDocumento20 paginePort Planning AssignmentPratama Rizqi AriawanNessuna valutazione finora

- GIS PaperDocumento8 pagineGIS PaperPratama Rizqi AriawanNessuna valutazione finora

- GIS PaperDocumento8 pagineGIS PaperPratama Rizqi AriawanNessuna valutazione finora

- Coastal Planning of Jakarta Waterfront - Pratama Rizqi Ariawan PDFDocumento5 pagineCoastal Planning of Jakarta Waterfront - Pratama Rizqi Ariawan PDFPratama Rizqi AriawanNessuna valutazione finora

- 10 Definitions of Sociology, Environment, Environmental SociologyDocumento4 pagine10 Definitions of Sociology, Environment, Environmental SociologyPratama Rizqi Ariawan100% (1)

- Coastal Reclamation GuidelinesDocumento13 pagineCoastal Reclamation GuidelinesPratama Rizqi AriawanNessuna valutazione finora

- Sustainable Development: From Brundtland To Rio 2012Documento26 pagineSustainable Development: From Brundtland To Rio 2012jesuistraduttrice100% (1)

- Integrated Coastal Planning of Jakarta WaterfrontDocumento6 pagineIntegrated Coastal Planning of Jakarta WaterfrontPratama Rizqi AriawanNessuna valutazione finora

- Industrial Air Pollution in PalembangDocumento1 paginaIndustrial Air Pollution in PalembangPratama Rizqi AriawanNessuna valutazione finora

- Beck WorldRiskDocumento18 pagineBeck WorldRiskHarsha VardhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Tourism PlanningDocumento7 pagineTourism PlanningAngel Mendez RoaringNessuna valutazione finora

- Learners Module q4Documento60 pagineLearners Module q4Melanie Tagudin TrinidadNessuna valutazione finora

- Results 2020: Climate Change Performance IndexDocumento32 pagineResults 2020: Climate Change Performance IndexTonyNessuna valutazione finora

- Asian ElephantsDocumento10 pagineAsian ElephantsTomato PotatoNessuna valutazione finora

- Fertis Products Details 08-05-19Documento1 paginaFertis Products Details 08-05-19venkat seshuNessuna valutazione finora

- INTA332 M5T2 Zeman CDocumento89 pagineINTA332 M5T2 Zeman CCatherine ZemanNessuna valutazione finora

- Decarbonization Plan - Costa RicaDocumento11 pagineDecarbonization Plan - Costa RicaEd King100% (1)

- Relationship Between Gross Primary Productivity, Net Primary Productivity and Plant RespirationDocumento25 pagineRelationship Between Gross Primary Productivity, Net Primary Productivity and Plant RespirationtahamidNessuna valutazione finora

- Green ManuringDocumento14 pagineGreen ManuringDr. Muhammad ArifNessuna valutazione finora

- Resources MCQs 50Documento3 pagineResources MCQs 50vipinNessuna valutazione finora

- ESWMA Implementation in Malolos CityDocumento7 pagineESWMA Implementation in Malolos CitySherry Gesim100% (1)

- Population and Consumption What We Know What We Need To Know-1Documento11 paginePopulation and Consumption What We Know What We Need To Know-1alefevianaNessuna valutazione finora

- Marcopper Mining Industry - Case StudyDocumento8 pagineMarcopper Mining Industry - Case StudyDanielle DiazNessuna valutazione finora

- M/S. Sri Kanakadurga Tribal Labour Contract Mutually Aided Co-Op Society.Documento11 pagineM/S. Sri Kanakadurga Tribal Labour Contract Mutually Aided Co-Op Society.Daneshwer VermaNessuna valutazione finora

- Soil Chemistry: Presented byDocumento22 pagineSoil Chemistry: Presented byZagreusNessuna valutazione finora

- 010 - 03-VCS+CCB Katingan - VerReport - Final - 20201115Documento67 pagine010 - 03-VCS+CCB Katingan - VerReport - Final - 20201115Putri HandayaniNessuna valutazione finora

- 54.0 - Waste Management v3.1 EnglishDocumento12 pagine54.0 - Waste Management v3.1 EnglishjbdejhiuhwNessuna valutazione finora

- Carl Paoli BioDocumento1 paginaCarl Paoli BioĐạt NguyễnNessuna valutazione finora

- 10 Ged 104 Global Migration BDocumento14 pagine10 Ged 104 Global Migration Brommel benamirNessuna valutazione finora

- ExtinctionDocumento36 pagineExtinctionabhishek 1100% (9)

- Proposed Title Group 5Documento2 pagineProposed Title Group 5Hisoka RyugiNessuna valutazione finora

- Soil and Water Conservation EngineeringDocumento247 pagineSoil and Water Conservation EngineeringRicardo F. Bernardinelli100% (1)

- Test 1 ECE CDB3022 - CEB3013 - May 2020Documento7 pagineTest 1 ECE CDB3022 - CEB3013 - May 2020Ahmed AlwaqediNessuna valutazione finora

- The Climate Change Act of 2009Documento2 pagineThe Climate Change Act of 2009Dieanne MaeNessuna valutazione finora

- Mohammed Corrected Seminar 2Documento23 pagineMohammed Corrected Seminar 2eyob eyasu80% (10)

- Turbine User Manual - Super Smelters LTD (1) - W. O.no. C-2567Documento200 pagineTurbine User Manual - Super Smelters LTD (1) - W. O.no. C-2567snehasish sowNessuna valutazione finora

- A Textbook of Botany. StrasburgerDocumento820 pagineA Textbook of Botany. StrasburgerKevin I. SanchezNessuna valutazione finora

- Science CFA - Energy TransferDocumento6 pagineScience CFA - Energy TransferHelina AmbayeNessuna valutazione finora

- Steffen, Rockstrom - AnthropoceneDocumento8 pagineSteffen, Rockstrom - AnthropocenevitorpindaNessuna valutazione finora

- CH311 Literature Review (Narelle) .Documento2 pagineCH311 Literature Review (Narelle) .Narelle IaumaNessuna valutazione finora