Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Debt Policy

Caricato da

Jed Darezz0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

36 visualizzazioni4 pagineReaction Paper on Debt Policy of the President of the Philippines

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

DOCX, PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoReaction Paper on Debt Policy of the President of the Philippines

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato DOCX, PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

36 visualizzazioni4 pagineDebt Policy

Caricato da

Jed DarezzReaction Paper on Debt Policy of the President of the Philippines

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato DOCX, PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 4

1

Jed Dares P. Tonogan Prof. Melanie Reteracion-Sartorio

2003 33843

PM 231 (Public Fiscal Administration)

Master of Management (Public Management)

College of Management

University of the Philippines Visayas

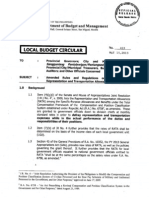

THE CURRENT PHILIPPINE BORROWING POLICY

The General Appropriations Act (GAA) of 2012 reflects the countrys financial plan for

the year, enacted by the Legislature and approved by the Executive. One important provision in

the 2012 GAA is on debt policy. General Provisions of the 2012 GAA states:

Sec. 14. Government Indebtedness and Guaranty. Notwithstanding any

provision of law to the contrary, the total indebtedness of the national government

and any of its agencies, offices, GOCCs, which carry the sovereign guaranty of

the Republic of the Philippines, shall not exceed 60% of the latest GDP.

If for any reason, the national government or any of its aforestated

subdivisions would need to borrow money and that would increase its total

indebtedness beyond 60% of the latest GDP, it may do so provided it obtains the

prior consent of Congress.

Total indebtedness includes the issuance of bonds, certificates, or any

other instrument which are the obligations of the national government and/or any

of its subdivisions or agencies with sovereign guaranty.

However, this provision of the 2012 GAA has been directly vetoed by President Aquino

in exercise of such privilege as provided by Law to the Executive. In his veto message to the

Congress, he says:

For the past years, Congress has consistently prescribed a debt cap in the

GAA. For FY 2012, it seeks to limit once again total government indebtedness to

sixty percent (60%) of gross domestic product (GDP).

While I recognize Congress noble intent behind the imposition of this

rule, I firmly believe that the GAA is not the proper legislative vehicle to amend

2

Presidential Decree No. 1961 (An Act Authorizing the President of the Philippines

to Enter into Foreign Currency Loan, Deposit and Guarantee Agreements and

Arrangements in support of the National Economic Recovery Program) and other

relevant laws such as RA No. 4860 (Foreign Borrowings Act). A change in our

borrowing policy ought to be more deliberately discussed and embodied in a

separate substantive law. For the foregoing reasons, I am constrained to

veto General Provisions, Section 14, Government Indebtedness and

Guaranty, page 1580.

Besides, no fiscal rule can take the place of governments unwavering

commitment to fiscal prudence and discipline, and this I have exhibited from the

very beginning of my Administration. Thus, our credit rating has thrice been

upgraded in my first year in office. Our average debt maturity has also been

extended from 7.9 to 9.2 years in a period of one year (June 2010 to June 2011).

Further, with the successful implementation of our international bond exchange

and buyback program, we have reduced our annual debt service cost from US$

69.6 Million to US$ 65 Million. Last, but not the least, is the significant reduction

of our consolidated public sector debt from 88.7% of GDP in 2005 to 73% by end

of 2010.

What can we imply on this borrowing policy of the Executive? First, we examine what

might be the positive effects of not putting a debt cap on our Budget.

The President contends that the GAA is not the proper venue to amend existing laws

which provide special powers to the Executive to enter into borrowing. Debt cap will have a

negative impact on government spending. It may limit spending on social services and

infrastructure. It should be remembered that the platform of government of the Noy Aquino

Administration is his Social Contract to the Filipino People. Narrowing the fiscal deficit and

public sector debt is a medium-term plan, so putting a debt cap is not practical at this time.

Furthermore, such debt cap may interfere with or may prevent government from taking

advantage of favorable market conditions. For example, in a period wherein the Peso is strong,

the Dollar is weak, and interest rates are low, the government can take advantage of this

condition by having more Peso-denominated debt to spend for social services and infrastructure.

3

We can also see the commitment of the Aquino Administration in the management of

debt. For instance, interest payments as a ratio of the budget dropped by 3% or a rough

equivalent of 37 billion pesos last year. So, we might as well give the Administration a chance to

be flexible in its liability management program, to better serve and manage the economy.

On the other hand, without such cap, several cons can also be expected. First in the list is

the risk of overborrowing. Congress primarily put this cap to prevent overborrowing. As an

example, several European governments are in the brink of bankruptcy because they

overborrowed.

With special powers given to the President to incur debt in behalf of the Philippines,

without limit, such powers may be abused and is prone to corruption.

Moreover, removal of such provision in the GAA which requires Malacaang to get

Congress approval if it exceeds the debt cap does not provide for checks and balances between

the two co-equal branches of the government.

Some civil society groups also contends that such veto is just in compliance and blind

obedience with borrowing policies set by the World Bank and other international financial

institutions. They accused the World Bank and these institutions of requiring country borrowers

to limit their spending on basic social services.

Do pros outweigh the cons with regards to this debt management issue? Of course, our

main objective in the management of debt is not to overborrow and to narrow our fiscal deficit

and public sector debt. However, we should also bear in mind that we need to spend for the basic

social services of the people as well as in infrastructure to improve our economy. Limiting our

borrowing, especially when market favors, is opportunity lost, and it entails economic cost. The

President, having vetoed such provision created by Congress should communicate well his

4

decision to constituents. He should prove that such veto is for societys general welfare rather

than a political exercise, or for personal gains. He should display his commitment by being

transparent to his liability management programs and he should disprove claims of critics that the

veto is just another abuse of executive privilege. Albeit there is no debt cap, he should try to limit

borrowing if not necessary and incur additional debt only when the market condition is

favorable.

There is no perfect debt policy. We cannot avoid incurring debt given our situation as a

country today. What is important is debt is properly managed, appropriately used to what it is

intended for, and serves general welfare of the public. Let us give the President a chance, the

flexibility he wishes in incurring debt for us. Let us just be vigilant that such privilege is not

corrupted and abused by the demons of the government.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- ADAC CreationDocumento3 pagineADAC CreationJed DarezzNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5795)

- Ageing Amount Not Yet Due DueDocumento2 pagineAgeing Amount Not Yet Due DueJed DarezzNessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- 00 1 PreambleDocumento8 pagine00 1 PreambleJed DarezzNessuna valutazione finora

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- COA Memo 2016-012Documento3 pagineCOA Memo 2016-012Jed DarezzNessuna valutazione finora

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Fraud ManualDocumento106 pagineFraud Manualagjeezy100% (9)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- LBC 103Documento10 pagineLBC 103Jed DarezzNessuna valutazione finora

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Athol Furniture, IncDocumento21 pagineAthol Furniture, Incvinoth kumar0% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Return On Marketing InvestmentDocumento16 pagineReturn On Marketing Investmentraj_thanviNessuna valutazione finora

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Financial DerivativesDocumento2 pagineFinancial Derivativesviveksharma51Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- микроDocumento2 pagineмикроKhrystyna Matsopa100% (1)

- Acc106 Rubrics For Assignment - For Student RefDocumento2 pagineAcc106 Rubrics For Assignment - For Student RefItik BerendamNessuna valutazione finora

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- Chapter 7: The Basics of Simple Interest (Time & Money) : Value (Or Equivalent Value)Documento4 pagineChapter 7: The Basics of Simple Interest (Time & Money) : Value (Or Equivalent Value)Ahmad RahhalNessuna valutazione finora

- The Scope and Challenge of International MarketingDocumento24 pagineThe Scope and Challenge of International MarketingBetty NiamienNessuna valutazione finora

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- 17 SynopsisDocumento40 pagine17 SynopsissekarkkNessuna valutazione finora

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Icaew Cfab Mi 2018 Sample Exam 3Documento30 pagineIcaew Cfab Mi 2018 Sample Exam 3Anonymous ulFku1v100% (2)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- Form 16 BDocumento1 paginaForm 16 BSurendra Kumar BaaniyaNessuna valutazione finora

- In003012 #W4243467Documento1 paginaIn003012 #W4243467İnsömnia ÇöğNessuna valutazione finora

- DB09154 Sales Assignment Project in PBMDocumento30 pagineDB09154 Sales Assignment Project in PBMParam SaxenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- What Are The Disadvantages To L'Oréal's Global Approach?Documento2 pagineWhat Are The Disadvantages To L'Oréal's Global Approach?Vivienne Rozenn Layto0% (1)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Invoice Act May 2022Documento2 pagineInvoice Act May 2022Pavan kumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Part 1: 1-2 Terminology For Six Month Merchandise PlanDocumento3 paginePart 1: 1-2 Terminology For Six Month Merchandise PlansiewspahNessuna valutazione finora

- Module 3 Debt ManagementDocumento33 pagineModule 3 Debt ManagementJane BañaresNessuna valutazione finora

- Infrastructure Financing And: Business ModelsDocumento9 pagineInfrastructure Financing And: Business ModelsAbhijeet JhaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- IFRS 9 - Financial InstrumentsDocumento63 pagineIFRS 9 - Financial InstrumentsMonirul Islam MoniirrNessuna valutazione finora

- ChallanFormDocumento1 paginaChallanFormAman GargNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 2 FranchisingDocumento34 pagineChapter 2 FranchisingPrinsesa EsguerraNessuna valutazione finora

- Model ALM PolicyDocumento9 pagineModel ALM Policytreddy249Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Business EnvironmentDocumento23 pagineBusiness Environmentniraj jainNessuna valutazione finora

- Globalization Is The Word Used To Describe The Growing Interdependence of The World's Economies, CulturesDocumento17 pagineGlobalization Is The Word Used To Describe The Growing Interdependence of The World's Economies, CulturesKiandumaNessuna valutazione finora

- Organizational Behavior: An Introduction To Your Life in OrganizationsDocumento25 pagineOrganizational Behavior: An Introduction To Your Life in OrganizationsAbraham kingNessuna valutazione finora

- Development Studies and The Development ImpasseDocumento7 pagineDevelopment Studies and The Development ImpasseAysha Junaid50% (2)

- RESPONSIBILITY ACCOUNTING - A System of Accounting Wherein Performance, Based OnDocumento8 pagineRESPONSIBILITY ACCOUNTING - A System of Accounting Wherein Performance, Based OnHarvey AguilarNessuna valutazione finora

- Profit Maximization: B-Pure MonopolyDocumento11 pagineProfit Maximization: B-Pure MonopolyChadi AboukrrroumNessuna valutazione finora

- Price Action SoftwareDocumento6 paginePrice Action SoftwaremjmariaantonyrajNessuna valutazione finora

- Maintenance RoiDocumento8 pagineMaintenance Roiganeshji@vsnl.comNessuna valutazione finora

- PDF Ministry 2011eng PDFDocumento154 paginePDF Ministry 2011eng PDFEugene TanNessuna valutazione finora

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)