Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Women in Middle Ages

Caricato da

Jirah Kaye Luison0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

71 visualizzazioni10 pagineThis paper is about women during the Medieval Ages, their stories, their lives, level of education, and married life

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoThis paper is about women during the Medieval Ages, their stories, their lives, level of education, and married life

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

71 visualizzazioni10 pagineWomen in Middle Ages

Caricato da

Jirah Kaye LuisonThis paper is about women during the Medieval Ages, their stories, their lives, level of education, and married life

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 10

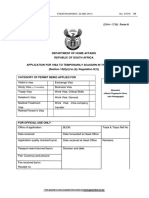

Division of Social Sciences

College of Arts and Sciences

University of the Philippines Visayas

In partial fulfillment of the

requirements in

History 100

Women in the Dark Ages

Submitted to:

Prof. Rey Carlo T. Gonzales

Submitted by:

Jirah Kaye B. Luison

October 8, 2010

Introduction

Europe during the Medieval Ages was mainly composed of landscapes that are very different

from those of modern Europe with its metropolises and many millions of people. In 200 CE, the

population of the continent was around 35 million. By 500 it had sunk to 27.5 million. In 650, after a

devastating pandemic of bubonic plague, along with other disasters, it plummeted to 18 million (Bitel,

2002).

The Christian Church was the most stable institution in the Middle Ages after the decline of the

Roman authority, providing unity and leadership. Most of the political powers lay in the hands of a few

landowning nobles though there are a handful of strong leaders who established kingdoms found

sporadically in some parts of Europe. The medieval life did not focus on grander or bigger groups like

national government but rather were based on the small worlds of the village, the castle, and the lords

manor. Gradually peace and prosperity returned to Europe. There was a growth of agriculture and trade,

and the towns bustled with activity. There was a revival in learning, also the arts and literature was able

to flourish. A few strong rulers began to create national states in England and France, and some

monarchs even challenged the Churchs authority in political life. By the high middle ages (1050-1270),

medieval civilization was in its height in Western Europe (Perry, Davis, Harris, Von Laue, & Warren,

1989).

But at the very beginning of the medieval ages according to Bitel (2002), when Europe was still

in transition, cities of the Roman north dwindled, along with their urban markets, the economic

exchange between city and countryside, urban industries, and urban professionals. Everywhere in the

continent, economies became subsistence ventures marked by sporadic local trade.

Feudal society was very much a mans world. In theory, women were held to be inferior to men;

in practice, they were subjected to male authority (Perry, Chase, Jacob, Jacob, & Laude, 1992). The

woman who had made her living by running a laundry or a wineshop no longer had products, costumers

or even a venue in which to do business. Prostitution, defined as sex for cash in a brothel, became

practically unknown in Europe. If a woman wished to trade upon her sex, she had to accept other

commodities besides cash in exchange and carry out her transactions, as the early Irish law put it

literally, in the bush (Bitel, 2002).

As Peasants and Noblewomen

Peasant women themselves left few records of their lives. Artists from the medieval world

pictured them at their seasonal tasks and celebrations, folklorists and anthropologists recorded their

words, songs, and stories. All testify to the sources of peasant womens strength: their veneration of the

land; their acceptance of responsibility for the survival of the family; their willingness to work; the

comfort they took in their beliefs. These dictated the rhythms of rural womens lives and the choices

they made through the centuries. From the time they were small children through maturity to old age,

rural women expected to work. They knew no division of labor, no separate spheres for women and

men. They worked everywhere (Anderson & Zinsser, 1988). In workplaces or private owned shops,

exploitation of female labor certainly was one of the worst forms of oppression by their employers. In

the peasant class women were about equivalent to if not as good as men at work (Le Goff, 1988).

While most unmarried noblewomen went to nunneries, peasant daughters, because they were

needed on the farm, rarely become nuns. Moreover, their parents could not afford the dowry, payable

in land, cash, or goods, required by the convent for admission(Perry, Chase, Jacob, Jacob, & Laude,

1992).

Whereas peasant women immerse themselves in their work and manual labor, the daughters of

nobility were said to be generally brought up for marriage and procreation. They were expected to

produce as many children as possible and they were usually married at around 16. Given the primitive

knowledge of obstetrics and hygiene, bearing children was even more dangerous than bearing a lance.

Many noblewomen died in childbirth, often literally exhausted by frequent successive births. Although

occasionally practiced, contraception was condemned both by the church and by husbands eager for

offspring (Kishlansky, Greary, & O'Brien, 2002).

In the upper class women, even though they had more refined pursuits, nevertheless were

economically active to an important degree. They ran womens workers, where by fancy skills such as

the meaning of fine materials, embroidery, and tapestry, they supplied a large proportion of the clothes

needed by the lord and his companions (Le Goff, 1988).

And as the lady of the castle, the lords wife performed important duties. She assigned tasks to

the servants, made medicines, preserved foods, taught girls how to spin, sew, and weave, and despite

her subordinate position, took charge of the castle when her husband is away. If the lord was taken

prisoner in war, she raised the ransom to pay for his release. Sometimes she put on armor and went to

war, for amusement, noblewomen enjoyed chess and other board games, played musical instruments,

or embroidered tapestries to cover castle walls. A lady might also join her husband on the hunt, a

favorite recreation of the medieval nobility (Perry, Chase, Jacob, Jacob, & Laude, 1992).

Family and Marriage

It is difficult to grasp the place which was held by women and children in the heart of this

primordial unit, the family, and also in assessing how they were able to evolve under conditions where

they live in. Saying that women were inferiors in the family group is beyond question. In this war faring,

and virile society, basic subsistence was always threatened. Consequently, fertility was more of a curse,

because of the interpretation of the Original Sin as having to do with sexual intercourse and procreation,

than a blessing, and women were not held in honor (Le Goff, 1988).

During these times, a young woman is expected to marry, thus creating a partnership with a

young man. But it does not mean that she has to give up her ties to her own family. She can even keep

the name of either his mother or father. It can be seen during the 15

th

century France when Joan of Arc

explained to the churchmen who questioned her at her trial that: I am called sometimes Jeanne dArc

and sometimes Jeanne Romoe, thus acknowledging her ties to both her parents (Anderson & Zinsser,

1988). But still, it is the fathers who arranged the marriage of their daughters. Girls from aristocratic

families were generally married at age 16 or younger to a man often twice their age. The wife of a lord

was at the mercy of her husband; if she angered him, she might expect a beating. A French law code of

the 13

th

century stated: In a number of cases men may be excused for the injuries they inflict on their

wives, nor should the law intervene. Provided he neither kills nor maims her, it is legal for a man to beat

his wife when she wrongs him (Perry, Chase, Jacob, Jacob, & Laude, 1992). So before, women were

obviously not treated equally by their husbands.

But inspire of their inferiority, Knights draw their strength and courage from their families: their

mothers, wives and children. Their squadrons or battalions, instead of being formed by chance or by an

accidental gathering, are composed of families and clans. Close to them are the people dearest to their

hearts and so they can hear the shrieks of women and cries of the children. They are the most sacred

witnesses of the mens bravery and most generous applauders. If wounded, the soldier brings his

wounded body to mother and wife, and they dont shrink from counting or demanding them and who

administers both food and encouragement to the combatants (Cantor, 1968).

The long absence of men at hunt, at the royal court, or on military expeditions left wives in

charge of the domestic scene for months or years at a time (Kishlansky, Greary, & O'Brien, 2002).

Women in the Church

Although the Church taught that both men and women were precious to God and spiritual

equals, Church tradition also regarded women as agents of the devil-the evil temptresses who. Like the

biblical Eve, lured men into sin-and Church law also permitted wife beating. In Mary, the mother of

Jesus, however, Christians had an alternative image of women to the image suggested by Eve, one that

placed women in a position of power (Perry, Chase, Jacob, Jacob, & Laude, 1992).

No longer a wife, a mother, a daughter, a woman, like a man, could dedicate herself to study

and prayer. Though not equal in nature or power to a monk, a nun could nonetheless share equal access

to divine favor, to knowledge, and to spiritual authority on Earth. From the 7

th

to 10

th

century, privileged

foundresses and abbesses could assume powers usually reserved to bishops, abbots and the ordained

clergy (Anderson & Zinsser, 1988).

The religious life in particular opened to aristocratic women possibilities of authority and

autonomy that had been previously been unknown in the West. Some women were already becoming

empowered and asserting their rights. An example of which is Saint Hilda of Whitby (614-680), an Anglo-

Saxon princess established and ruled a religious community that included both women and men. It was

in Hildas community that the Synod of Whitby took place, and Hilda played an active role, advising the

king and assembled bishops (Kishlansky, Greary, & O'Brien, 2002).

Aristocratic girls who did not marry often entered a convent. The talents of these unmarried

noblewomen were provided of an outlet by the nunneries. The organizational skills of abbesses are

showcased in their ways of supervising the convents daily affairs; some acquired an education and, like

their male counterparts, copied manuscripts, and thus preserved knowledge and ideas of the past.

Hreswitha (c. 695-c. 1001) of Gandersheim in Saxony, Germany, was a nun who produced poetry, history

and dramas. Inspired by the poet Terrence, she wrote 6 dramas- the first since Roman times- along with

a history of German rulers and one of her own convent. Establishment of cathedral schools and

universities that were obviously male and taught by men-unlike these monasteries where women

frequently taught- reduced the influence of women, however (Perry, Chase, Jacob, Jacob, & Laude,

1992).

By the 13

th

century, attitudes towards womens role in the church had crystallized around these

male concerns, this medley of traditional fears of the female as a sexual being. Yes, allow the woman a

life devoted to religion but then they must be closely guarded and isolated because of the dangers

attributed to her being a woman. Nuns must be separated from men, even those of high faith. There

were prohibitions against nuns teaching boys, against any but the necessary contacts between the

women and their male confessors, gained wide acceptance. Even more important, women must be kept

strictly cloistered. They were not allowed to leave the convent; they should not have contact with

people outside their walls (Anderson & Zinsser, 1988).

Women in the Society

Within this aristocratic society, women played a wider and more active role than before during

the Roman or barbarian antiquity. In part, womens new role was due to the influence of Christianity,

which recognized the distinct-though always inferior-rights of women, fought against the barbarian

tradition of allowing chieftains numerous wives, and acknowledged womens right to lead a cloistered

religious life. In addition, the construction of Germanic and Roman familial traditions permitted women

to participate in court proceedings, to inherit and dispose of properties, and, if widowed, to serve as

tutors and guardians of their minor children (Kishlansky, Greary, & O'Brien, 2002).

Le Goff (1988) said that it has often been claimed that the crusades meant that the womens

power and rights increased because it left women on their own in the Western Europe. And the

condition of women had improved on two stages, in the Carolingian period and the time of the crusades

and reconquistas.

But Kishlansky, et. al (2002) disagreed with this and held that in the martial society the political

and economic status of women declined considerably. Because they were considered unable to

participate in warfare, women in Western Europe were also frequently excluded from inheritance,

estate management, and public deliberations. Although a growing tradition of courtliness glorified

aristocratic women in literature, women were actually losing ground in the real world. Some

noblewomen did control property and manage estates, but usually such roles were possible only for

widows who had borne sons and who could play a major part in raising them. For all chivalric rhetoric,

women did not enjoy which status in medieval society. Some men nevertheless apparently felt

threatened by women and female sexuality. Secular tradition and Christian teaching portrayed women

as devious, sexually demanding temptresses who were often responsible for the corruption and

downfall of men. Many men also resented the power wielded by wealthy widows and abbesses.

Women and Literature

A form of medieval poetry, which flourished particularly in Provence, in southern France, dealt

with the romantic glorification of women. Sung by troubadours, many of them nobles, the country love

poetry expressed a changing attitude towards women. Although medieval men generally regarded

women as inferior and subordinate, courtly love poetry ascribed to noble ladies superior qualities of

virtue. To the nobleman, the lady became a goddess worthy of all devotion, loyalty, and worship. He

would honor her and serve her as he did his lord; for her love he would undergo any sacrifice.

Troubadours sang love songs that praised ladies for their beauty and charm and expressed with the joys

and pairs of love. Noblewomen actively influenced the rituals and literature of courtly love. They often

invite poets to their courts and even wrote poetry themselves. There are times when a lady troubadour

would express her love for her Knight and disdain for her husband. Ladies demanded that knights treat

them with gentleness and consideration and that knights dress neatly, bathe often, play instruments,

and compose (or at least recite) poetry. To prove worthy of his ladys love, a knight had to demonstrate

patience, charm, bravery, and loyalty. By devoting himself to a lady, it was believed, a knight would

ennoble his character (Perry, Chase, Jacob, Jacob, & Laude, 1992).

Ridicule of Achievements

Not only did the Church restrict and confine women, but the facts of their past achievements

and authority were ridiculed, the woman remembered for exceptional learning, piety and power was

not Lioba, Saint Hilda, Herrad of Landsberg, or Hildegard of Bingen. Instead the fantasy of a 13

th

century

French Dominican, Steven of Bourbon, was passed on from generation to generation, the tale of

fictitious Pope Joan. In the story, Joan studied, disguised as man. Brilliant and devout, she advanced

quickly within the order, went to Rome, became a cardinal, and then was selected as Pope. But in this

life of achievement, this life without restriction, her womans matrix betrayed her. In Rome, she insisted

for a young man, she fornicated, and she met a fitting end. On the day of her installation as Pope, she

died in childbirth during the inaugural procession through the streets, death in the gutters of Rome like

a common whore. A salacious, cautionary fable displaced the memory of the lives and writings of the

great abbesses and their women scholars (Anderson & Zinsser, 1988).

Notable Women

Joan of Arc (1412-1481), the extraordinary sixteen-year-old daughter of a French peasant family,

defied almost every tradition of the peasant womens world. She disobeyed her parents, importuned

whose above her station for help, and insisted that she must act outside the womens accepted roles.

Joan told everyone that she had been sent by God to join the army of the King of France and to raise the

English siege of the town of Orleans. Everything about her manner, her demands and her actions were

unorthodox. They came to perceive her as a heroine: the holy maiden warrior, zealous and strong, sent

for the salvation of the kingdom. So perceived, Joans passion, energy, persistence, and ingenuity gained

her power and success in roles traditionally reserved to men and to men of higher caste as well

(Anderson & Zinsser, 1988).

Clare of Assisi was an eighteen-year-old daughter of the Count of Sesso-Rosso. According to

Anderson and Zinsser (1988), she defied her family to gain approval from Saint Francis of Assisi for her

group of pious women at the Church of St. Damien. Saint Clare and her followers did almost succeed in

creating their own new role with no allegiance owed to a male order, later in the 13

th

century where

women like Agnes of Bohemia, the betrothed of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I, and Margaret,

wife of King Louis IX of France, founded establishments and called themselves poor Clares and not

Franciscan.

Williams great grandson, Henry acquired much of southern France through his marriage to

Eleanor of Aquitaine (c. 1122-1204), perhaps the most powerful queen of the medieval era (Perry,

Chase, Jacob, Jacob, & Laude, 1992). She was the heiress of the greatest principalities of France, wife of

two kings and mother of two more (Kishlansky, Greary, & O'Brien, 2002). In their study of women in

Europe, Anderson and Zinsser (1988) found that Eleanor came to her lands because of a series of deaths

in her family including her parents and her brother, leaving her to the care of King Louis VI of France.

And he grabbed the opportunity to marry her to his seventeen-year-old son. She divorced him in 1152

and married Henry, the heir to the English throne. Together, they ruled half of France and all of England.

At seventy-two, Eleanor was able to raise an army.

Anderson and Zinsser (1988) mentioned two more influential women, Saint Catherine of Siena

and Saint Bridget of Sweden. Catherine Bemincasa (1347-1380) became the patron saint of Italy and was

honored as doctor of the Church. She refused marriage, seen cutting her hair in protest and at eighteen

became a Dominican Tertiary. Saint Bridget of Sweden (1303-1373), also a noblewoman, made many of

the same choices as Saint Elizabeth. She had visions of Jesus, John the Baptist, Saint Agnes and the Virgin

Mary. She condemned the vanities of women, the laxity of archbishops, cursing queens and kings for

what she viewed as their sexual depravity.

Conclusion

One cannot say that womens lives were easy during the Dark Ages. The difficulties may be

attributed to the society, influence of Christianity, bias of men in general and even to the women

themselves. They were not given the same opportunity as to those of men and an equal status with men

is difficult, if not impossible, to achieve. But the medieval ages played a large part in molding the history

of women especially those who made a difference and asserted their rights as a human being. Centuries

have passed since those times but we still can see traces of discrimination and abuse in todays society.

Works Cited

Anderson, B. S., & Zinsser, J. P. (1988). a History of their Own: Women in Europe from Prehistory to the

Present (Vol. 1). New York: Harper and Row Publishers.

Bitel, L. M. (2002). Women in Early Medieval Europe, 400-1000. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cantor, N. F. (Ed.). (1968). The Medieval World. Toronto: The Macmillan Company.

Kishlansky, M., Greary, P., & O'Brien, P. (2002). A Brief History of Western Civilization: The Unfinished

Legacy. USA: Addison-Wesley Educational Publishers, Inc.

Le Goff, J. (1988). Medieval Civilization. (J. Barrow, Trans.) Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Perry, Chase, Jacob, Jacob, & Laude, V. (1992). Western Civilization: Ideas, Politics and Society (4th ed.).

Boston, Massachusets: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Perry, M., Davis, D., Harris, J., Von Laue, T., & Warren, D. (1989). A History of the World. Boston:

Houghton Mifflin Company.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Listing of Internet Slang and AcronymsDocumento4 pagineListing of Internet Slang and AcronymsabeegameNessuna valutazione finora

- Masquerade Novelty, Inc. v. Unique Industries, Inc., and Everett Novak, An Individual, 912 F.2d 663, 3rd Cir. (1990)Documento14 pagineMasquerade Novelty, Inc. v. Unique Industries, Inc., and Everett Novak, An Individual, 912 F.2d 663, 3rd Cir. (1990)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- First Church of Seventh-Day Adventists Weekly Bulletin (Spring 2013)Documento12 pagineFirst Church of Seventh-Day Adventists Weekly Bulletin (Spring 2013)First Church of Seventh-day AdventistsNessuna valutazione finora

- BS-300 Service Manual (v1.3)Documento115 pagineBS-300 Service Manual (v1.3)Phan QuanNessuna valutazione finora

- Family Worship PDF - by Kerry PtacekDocumento85 pagineFamily Worship PDF - by Kerry PtacekLeo100% (1)

- BalayanDocumento7 pagineBalayananakbalayanNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter Xiii: Department of Public Enterprises: 13.1.1 Irregular Payment To EmployeesDocumento6 pagineChapter Xiii: Department of Public Enterprises: 13.1.1 Irregular Payment To EmployeesbawejaNessuna valutazione finora

- 400 Series Temperature Controls: PART I - InstallationDocumento4 pagine400 Series Temperature Controls: PART I - InstallationDonian Liñan castilloNessuna valutazione finora

- Prepared For: Lecturer's Name: Ms. Najwatun Najah BT Ahmad SupianDocumento3 paginePrepared For: Lecturer's Name: Ms. Najwatun Najah BT Ahmad SupianBrute1989Nessuna valutazione finora

- 2000 CensusDocumento53 pagine2000 CensusCarlos SmithNessuna valutazione finora

- Request For Inspection: Ain Tsila Development Main EPC Contract A-CNT-CON-000-00282Documento1 paginaRequest For Inspection: Ain Tsila Development Main EPC Contract A-CNT-CON-000-00282ZaidiNessuna valutazione finora

- It's That Time of Year Again - Property Tax Payments Due: VillagerDocumento16 pagineIt's That Time of Year Again - Property Tax Payments Due: VillagerThe Kohler VillagerNessuna valutazione finora

- Concept Note ALACDocumento4 pagineConcept Note ALACdheereshkdwivediNessuna valutazione finora

- Exchange Content UpdatesDocumento2.163 pagineExchange Content UpdatesAlejandro Cortes GarciaNessuna valutazione finora

- Petitioner Vs Vs Respondent: First DivisionDocumento4 paginePetitioner Vs Vs Respondent: First DivisionAndrei Anne PalomarNessuna valutazione finora

- Tanganyika Buffer SDS 20160112Documento8 pagineTanganyika Buffer SDS 20160112Jorge Restrepo HernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- MURS320: Vishay General SemiconductorDocumento5 pagineMURS320: Vishay General SemiconductorAgustin DiocaNessuna valutazione finora

- Punjab National BankDocumento28 paginePunjab National Bankgauravdhawan1991Nessuna valutazione finora

- Kinds of CorporationDocumento1 paginaKinds of Corporationattyalan50% (2)

- ASME - Lessens Learned - MT or PT at Weld Joint Preparation and The Outside Peripheral Edge of The Flat Plate After WDocumento17 pagineASME - Lessens Learned - MT or PT at Weld Joint Preparation and The Outside Peripheral Edge of The Flat Plate After Wpranav.kunte3312Nessuna valutazione finora

- Account STDocumento1 paginaAccount STSadiq PenahovNessuna valutazione finora

- Ami Aptio Afu User Guide NdaDocumento32 pagineAmi Aptio Afu User Guide NdaMarcoNessuna valutazione finora

- (DHA-1738) Form 8: Department of Home Affairs Republic of South AfricaDocumento20 pagine(DHA-1738) Form 8: Department of Home Affairs Republic of South AfricaI QNessuna valutazione finora

- Cirrus 5.0 Installation Instructions EnglishDocumento62 pagineCirrus 5.0 Installation Instructions EnglishAleksei PodkopaevNessuna valutazione finora

- Jison V CADocumento2 pagineJison V CACzarina Lea D. Morado0% (1)

- Peavey Valveking 100 212Documento12 paginePeavey Valveking 100 212whitestratNessuna valutazione finora

- Candlestick Charting: Quick Reference GuideDocumento24 pagineCandlestick Charting: Quick Reference GuideelisaNessuna valutazione finora

- Tax Invoice/Bill of Supply/Cash Memo: (Original For Recipient)Documento1 paginaTax Invoice/Bill of Supply/Cash Memo: (Original For Recipient)MelbinGeorgeNessuna valutazione finora

- Sameer Vs NLRCDocumento2 pagineSameer Vs NLRCRevz Lamoste100% (1)

- Passbolt On AlmaLinux 9Documento12 paginePassbolt On AlmaLinux 9Xuân Lâm HuỳnhNessuna valutazione finora