Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Brown Mcneill 1966

Caricato da

Imran Imran0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

338 visualizzazioni13 pagineBrown

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoBrown

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

338 visualizzazioni13 pagineBrown Mcneill 1966

Caricato da

Imran ImranBrown

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 13

JOURNAL OF VERBAL LEARNING AND VERBAL BERAVIOR 5, 3 2 5 - 3 3 7 ( 1 9 6 6 )

The "Tip of the Tongue" Phenomenon

ROGER BROWN AND DAVID McNEILL 1

Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts

The "tip of the tongue" (TOT) phenomenon is a state in which one cannot quite

recall a familiar word but can recall words of similar form and meaning. Several hundred

such states were precipitated by reading to Ss the definitions of English words of low

frequency and asking them to try to recall the words. It was demonstrated that while in

the TOT state, and before recall occurred, Ss had knowledge of some of the letters in the

missing word, the number of syllables in it, and the location of the primary stress. The

nearer S was to successful recall the more accurate the information he possessed. The re-

call of parts of words and attributes of Words is termed "generic recall." The interpreta-

tion offered for generic recall involves the assumption that users of a language possess the

mental equivalent of a dictionary. The features that figure in generic recall may be

entered in the dictionary sooner than other features and so, perhaps, are wired into a

more elaborate associative network. These more easily retrieved features of low-

frequency words may be the features to which we chiefly attend in word-perception.

"lnae features favored by attention, especially the beginnings and endings of words,

appear to carry more information than the features that are not favored, in particular

the middles of words.

Wi l l i am James wrote, i n 1893: "Suppose

we t ry to recall a forgotten name. The state

of our consciousness is peculiar. There is a

gap therein; but no mere gap. I t is a gap

t hat is i nt ensel y active. A sort of wrai t h of

the name is in it, beckoni ng us in a given

direction, maki ng us at moment s tingle with

the sense of our closeness and then l et t i ng

us sink back wi t hout the longed-for term. If

wrong names are proposed to us, this singu-

l arl y definite gap acts i mmedi at el y so as to

negate them. They do not fit into its mould.

And the gap of one word does not feel like

the gap of another, all empt y of cont ent as

bot h mi ght seem necessarily to be when de-

scribed as gaps" (p. 251).

The "t i p of the t ongue" ( TOT) state in-

volves a failure to recall a word of which one

has knowledge. The evidence of knowledge is

either an event ual l y successful recall or else

an act of recognition t hat occurs, wi t hout

a Now at the University of Michigan.

1966 by Academic Press Inc.

addi t i onal training, when recall has failed.

The class of cases defined by the conj unct i on

of knowledge and a failure of recall is a

large one. The TOT state, which James de-

scribed, seems to be a small subclass in which

recall is felt to be i mmi nent .

For several mont hs we watched for TOT

states i n ourselves. Unabl e to recall the name

of the street on which a relative lives, one

of us t hought of Congress and Corinth and

Concord and then looked up the address

and learned t hat it was Cornish. The words

t hat had come to mi nd have certain proper-

ties in common with the word t hat had been

sought (the "t arget wor d") : all four begin

with Co; all are two-syllable words; all put

the pri mary stress on the first syllable. After

this experience we began put t i ng direct ques-

tions to ourselves when we fell into the TOT

state, questions as to the number of syllables

in the target word, its initial letter, etc.

Woodwort h (1934), before us, made a

record of dat a for nat ural l y occurring TOT

325

326 BROWN AND MCNEILL

s t at es and Wenzl ( 1932, 1936) di d t he same

for Ge r ma n wor ds. The i r r esul t s ar e s i mi l ar

to t hose we obt a i ne d and cons i s t ent wi t h t he

f ol l owi ng pr e l i mi na r y char act er i zat i on. Wh e n

compl et e r ecal l of a wor d is not pr e s e nt l y

possi bl e but is f el t t o be i mmi nent , one can

of t en cor r ect l y r ecal l t he gener al t ype of t he

wor d; generic r ecal l ma y succeed when par -

t i cul ar r ecal l fai l s. The r e seem t o be t wo

common var i et i es of gener i c r ecal l . ( a )

Somet i mes a p a r t of t he t ar get wor d is

r ecal l ed, a l et t er or t wo, a s yl l abl e, or affix.

Pa r t i a l r ecal l is neces s ar i l y al so generic si nce

t he cl ass of wor ds def i ned b y t he possessi on

of a n y part of t he t a r ge t wor d wi l l i ncl ude

wor ds ot her t ha n t he t ar get . ( b) Somet i mes

t he a bs t r a c t f or m of t he t a r ge t is r ecal l ed,

pe r ha ps t he f act t ha t i t was a t wo- s yl l abl e

sequence wi t h t he p r i ma r y st r ess on t he f i r st

s yl l abl e. The whol e wor d is r epr es ent ed i n

abst ract f or m recall but not on t he l et t er -

by- l e t t e r l evel t ha t cons t i t ut es i t s i de nt i t y.

The r ecal l of an a b s t r a c t f or m i s al so neces-

s ar i l y generic, si nce a ny such f or m def i nes a

cl ass of wor ds ext endi ng be yond t he t ar get .

We nz l and Woodwor t h had wor ked wi t h

smal l col l ect i ons of da t a for na t ur a l l y oc-

cur r i ng T OT st at es. Thes e d a t a were, for

t he most pa r t , pr ovi de d b y t he i nves t i gat or s ;

wer e col l ect ed i n an uns ys t e ma t i c f ashi on;

and were a na l yz e d in an i mpr es s i oni s t i c non-

qua nt i t a t i ve way. I t seemed t o us t ha t such

d a t a l ef t t he f act s of gener i c r ecal l i n doubt .

An occasi onal cor r es pondence bet ween a re-

t r i eved wor d a nd a t ar get wor d wi t h r es pect

t o number of s yl l abl es , st r ess p a t t e r n or i ni -

t i al l et t er is, a f t e r al l , t o be expect ed b y

chance. Sever al mont hs of " s e l f - obs e r va t i on

and a s ki ng- our - f r i e nds " yi e l de d fewer t han a

dozen good cases a nd we r eal i zed t ha t an

i mpr ove d me t hod of d a t a col l ect i on was

essent i al .

We t hought i t mi ght p a y t o " p r o s p e c t "

for T OT s t at es by r e a di ng t o S def i ni t i ons

of uncommon Engl i s h wor ds a nd as ki ng hi m

t o s uppl y t he wor ds. Th e pr oc e dur e was

gi ven a pr e l i mi na r y t es t wi t h ni ne Ss who

were i ndi vi dua l l y i nt er vi ewed for 2 hr s each. 2

I n 57 i ns t ances an S was, i n f act , " s e i z e d"

b y a T OT st at e. The si gns of i t wer e un-

mi s t a ka bl e ; he woul d a ppe a r to be i n mi l d

t or me nt , s omet hi ng l i ke t he br i nk of a

sneeze, and i f he f ound t he wor d hi s r el i ef

was cons i der abl e. Whi l e s ear chi ng for t he

t ar get S t ol d us al l t he wor ds t h a t came t o

hi s mi nd. He vol unt eer ed t he i nf or ma t i on

t ha t some of t hem r es embl ed t he t ar get i n

s ound but not in meani ng; ot her s he was

sur e wer e s i mi l ar i n meani ng b u t not i n

sound. The E i nt r ude d on S' s a gony wi t h

t wo ques t i ons : ( a ) How ma n y s yl l abl es has

t he t a r ge t wor d? ( b) Wh a t is i t s fi rst l et t er ?

Answer s t o t he fi rst ques t i on wer e cor r ect

i n 47% of al l cases and answer s t o t he

second ques t i on wer e cor r ect i n 51% of t he

cases. The s e out comes encour aged us t o be-

l i eve t ha t gener i c r ecal l was r eal and to de-

vi se a gr oup pr oc e dur e t ha t woul d f ur t her

speed up t he r at e of da t a col l ect i on.

METHOD

Subj ect s

Fifty-six Harvard and Radcliffe undergraduates

participated in one of three evening sessions; each

session was 2 hrs long. The Ss were volunteers

from a large General Education Course and were

paid for their time.

Word List. The list consisted of 49 words which,

according to the Thorndike-Lorge Word Book

(1952) occur at least once per four million words

but not so often as once per one million words.

The level is suggested by these examples: apse,

nepotism, cloaca, ambergris, and sampan. We

thought the words used were likely to be in the

passive or recognition vocabularies of our Ss but

not in their active recall vocabularies. There were

6 words of 1 syllable; 19 of 2 syllables; 20 of 3

syllables; 4 of 4 syllables. For each word we used

a definition from The American College Dictionary

(Barnhart, 1948) edited so as to contain no words

that closely resembled the one being defined.

Response Sheet. The response sheet was laid

off in vertical columns headed as follows:

Intended word (d- One I was thinking of).

(-- Not).

2 We wish to thank Mr. Charles Hollen for

doing the pretest interviews.

a TI P OF THE TONGUE" PHENOMENON 327

Number o] syllables (1-5).

Initial letter.

Words oJ similar sound. (1. Closest in sound )

(2. Middle )

(3. Farthest in Sound)

Words oJ similar meaning.

Word you had in mind i] not intended word.

Pr oc e dur e

We i ns t r uc t e d Ss t o t he f ol l owi ng effect.

I n t hi s e xpe r i me nt we ar e c onc e r ne d wi t h t h a t

s t at e of mi n d i n whi c h a per s on is una bl e t o

t h i n k of a wo r d t h a t he is cer t ai n he knows , t he

s t a t e of mi n d i n whi c h a wo r d s eems t o be on

t he t i p of one' s t ongue. Our t e c hni que f or pr e -

ci pi t at i ng s uc h s t at es is, i n gener al , t o r ead deft -

ni f i ons of u n c o mmo n wor ds a n d a s k t he s ubj e c t

to recal l t he wor d.

(1) We wi l l f i r st r e a d t he def i ni t i on of a l ow-

f r e que nc y wor d.

(2) I f you s houl d h a p p e n t o k n o w t he wo r d

a t once, or t hi nk y o u do, or, i f y o u s houl d s i mpl y

n o t k n o w i t , t he n t he r e is n o t h i n g f ur t he r f or

you to do a t t he mo me n t . 5 u s t wai t .

(3) I f y o u ar e una bl e to t h i n k of t he wo r d

b u t feel s ur e t h a t y o u k n o w i t a n d t h a t i t is on

t he ver ge of c omi ng back to y o u t he n y o u ar e

i n a T OT s t a t e a n d s houl d begi n a t once to fill

i n t he c o l u mn s of t he r es pons e sheet .

(4) Af t e r r e a di ng each def i ni t i on we will as k

wh e t h e r a n y o n e is i n t he T OT s t at e. An y o n e wh o

is i n t h a t s t a t e s houl d rai se hi s h a n d . Th e r e s t of

us wi l l t h e n wa i t unt i l t hos e i n t he T OT s t a t e

h a v e wr i t t e n on t he a ns we r s heet al l t he i n f o r ma -

t i on t he y ar e abl e to pr ovi de.

(5) Wh e n e ve r yone wh o ha s been i n t he TOT

s t a t e ha s si gnal l ed us t o pr oceed, we wi l l r e a d

t he t a r ge t wor d. At t hi s t i me, e ve r yone i s t o

wr i t e t he wo r d i n t he l e f t mos t c ol umn of t he

r es pons e sheet . Th o s e of y o u who h a v e k n o wn

t he wo r d si nce f i r st i t s def i ni t i on was r e a d ar e

a s ke d n o t t o wr i t e i t unt i l t hi s poi nt . Thos e of

y o u wh o s i mpl y di d n o t k n o w t he wo r d or wh o

h a d t h o u g h t of a di f f er ent wo r d will wr i t e n o w

t he wo r d we r ead. For t hos e of y o u who h a v e

been i n t he T OT s t a t e t wo e ve nt ua l i t i e s ar e pos -

sible. Th e wo r d r e a d ma y st r i ke y o u as def i ni t el y

t he wo r d y o u h a v e been seeki ng. I n t h a t case

pl ease wr i t e ' + ' a f t e r t he wor d, as t he i ns t r uc -

t i ons a t t he h e a d of t he c o l u mn di rect . Th e ot he r

possi bi l i t y is t h a t y o u will n o t be s ur e wh e t h e r

t he wo r d r e a d is t he one y o u h a v e be e n s eeki ng

or, i ndeed, y o u ma y be s ur e t h a t i t is not . I n t hi s

case y o u ar e a s ke d t o wr i t e t he si gn ' - - ' a f t e r

t he wor d. Some t i me s wh e n t he wo r d r e a d o u t

is n o t t he one y o u h a v e been s eeki ng y o u r a c t ua l

t a r ge t ma y c ome to mi nd. I n t hi s case, i n a ddi -

t i on t o t he mi n u s si gn i n t he l e f t mos t c ol umn,

pl ease wr i t e t he a c t ua l t a r ge t wo r d i n t he r i ght -

mo s t c ol umn.

( 6) No w we c ome t o t he c o l u mn ent r i es

t hems el ves . Th e fi rst t wo ent r i es, t he gues s as t o

t he n u mb e r of syl l abl es a n d t he i ni t i al l et t er , ar e

r equi r ed. Th e r e ma i ni ng ent r i es s houl d be filled

o u t i f possi bl e. Wh e n y o u ar e i n a T OT s t at e,

wor ds t h a t ar e r el at ed to t he t a r ge t word. do

a l mo s t a l wa ys c ome t o mi nd. Li s t t h e m as t h e y

come, b u t s e pa r a t e wor ds whi c h y o u t h i n k r e-

s embl e t he t a r ge t i n s o u n d f r o m wo r d s whi c h y o u

t h i n k r es embl e t he t a r ge t i n me a ni ng.

(7) Wh e n y o u h a v e f i ni shed al l y o u r ent r i es,

b u t bef or e y o u si gnal us to r e a d t he i n t e n d e d

t a r ge t wor d, l ook a ga i n at t he wo r d s y o u h a v e

l i st ed as ' Wo r d s of s i mi l ar s ound. ' I f possi bl e,

r a n k t hese, as t he i ns t r uc t i ons a t t he h e a d of t he

c ol umn di r ect , i n t e r ms of t he degr ee of t hei r

s e e mi ng r es embl ance t o t he t ar get . Thi s mu s t be

done wi t h o u t knowl e dge of wh a t t he t a r ge t ac-

t ual l y is.

(8) Th e s ear ch pr oc e dur e of a per s on i n t he

TOT s t a t e will s ome t i me s s er ve t o r et r i eve t he

mi s s i ng wo r d bef or e he has f i ni shed fi l l i ng i n t he

c ol umns a n d bef or e we r e a d o u t t he wor d. Wh e n

t hi s h a p p e n s pl ease ma r k t he pl ace whe r e i t

h a p p e n s wi t h t he wor ds " Go t i t " a n d do not

provide any more data.

RESULTS

Cl asses of Da t a

The r e wer e 360 i ns t ances , acr os s al l wo r d s a n d

al l Ss, i n whi c h a T OT s t a t e was si gnal l ed. Of

t hi s t ot al , 233 wer e pos i t i ve TOTs . A pos i t i ve T OT

i s one f or whi c h t he t a r ge t wo r d is k n o wn and,

c ons e que nt l y, one f or whi c h t he d a t a obt a i ne d can

be scor ed as a c c ur a t e or i naccur at e. I n t hos e cases

whe r e t he t a r ge t was n o t t he wo r d i nt e nde d b u t

s ome ot he r wo r d whi c h S f i nal l y r ecal l ed a n d wr ot e

i n t he r i g h t mo s t c ol umn hi s d a t a wer e checked

a ga i ns t t h a t wor d, hi s effect i ve t ar get . A ne ga t i ve

T OT is one f or whi c h t he S j udge d t he wo r d r e a d

o u t n o t t o ha ve been hi s t a r ge t a nd, i n addi t i on,

one i n whi c h S p r o v e d una bl e t o recal l hi s o wn

f unc t i ona l t ar get .

Th e da t a pr ovi de d by S whi l e he s ear ched f or

t he t a r ge t wo r d ar e of t wo ki nds : expl i ci t guesses

as t o t he n u mb e r of syl l abl es i n t he t a r ge t a n d t he

i ni t i al l et t er of t he t a r ge t ; wor ds t h a t c a me t o mi n d

whi l e he s e a r c he d f or t he t ar get . Th e wo r d s t h a t

c a me t o mi n d wer e classified b y S i nt o 224 wor ds

s i mi l ar i n s o u n d t o t he t ar get ( he r e a f t e r cal l ed " SS"

wor ds ) a n d 95 wor ds si mi l ar i n me a n i n g t o t he

328 BROWN AND MC NEILL

target (hereafter called "SM" words). The S's in-

formation about the number of syllables in, and

the initial letter of the target may be inferred from

correspondences between the target and his SS words

as well as directly discovered: from his explicit

guesses. For his knowledge of the stress pattern of

the target and of letters in the target, other t han

the initial letter, we must rely on the SS words

alone since explicit guesses were not required.

To convey a sense of the SS and SM words we

offer the following examples. When the target was

sampan the SS words (not all of them real words)

included: Saipan, Siam, Cheyenne, sarong, sanching,

and sympoon. The SM words were: barge, house-

boat, and junk. When the target was caduceus the

SS words included: Casadesus, AescheIus, cephalus,

and leucosis. The SM words were: fasces, Hippo-

crates, lictor, and snake. The spelling in all cases

is S's own.

We will, in this report, use the SM words to

provide baseline data against which to evaluate

the accuracy of the explicit guesses and of the SS

words. The SM words are words produced under

the spell of the positive TOT state but judged by

S to resemble the target in meaning rather than

sound. We are quite sure t hat the SM words are

somewhat more like the target than would be a

collection of words produced by Ss with no knowl-

edge of the target. However, the SM words make

a better comparative baseline than any other data

we collected.

General Problems o/ Analysis

The data present problems of analysis t hat are

not common in psychology. To begin with, the

words of the list did not reliably precipitate TOT

states. Of the original 49 words, all but zither suc-

ceeded at least once; the range was from one success

to nine. The Ss made actual targets of 51 words

not on the original list and all but five of these

were pursued by one S only. Clearly none of the

100 words came even close to precipitating a TOT

state in all 56 Ss. Furthermore, the Ss varied in

their susceptibility to TOT states. There were nine

who experienced none at all in a 2-hr period; the

largest number experienced in such a period by one

S was eight. In out data, then, the entries for one

word will not usually involve the same Ss or even

the same number of Ss as the entries for another

word. The entries for one S need not involve the

same words or even the same number of words as

the entries for another S. Consequently for the tests

we shall want to make there are no significance tests

that we can be sure are appropriate.

In statistical theory our problem is called the

"fragmentary data problem. '',~ The best thing to do

with fragmentary data is to report them very fully

and analyze them in several different ways. Our

detailed knowledge of these data suggests that

the problems are not serious for, while there is

some variation in the pull of words and the sus-

ceptibility of Ss there is not much variation in the

quality of the data. The character of the material

recalled is much the same from word to word and

S t oS.

Number of Syllables

As t he ma i n i t em of evi dence t ha t S i n a

TOT s t at e can recal l wi t h si gni f i cant success

t he numbe r of syl l abl es i n a t a r ge t wor d he

has not yet f ound we offer Ta bl e 1. The

ent r i es on t he di agonal ar e i ns t ances i n whi ch

guesses wer e cor r ect . The or der of t he means

of t he expl i ci t guesses is t he s ame as t he

or der of t he act ual numbe r s of syl l abl es i n

t he t ar get wor ds. The r a nk or der cor r el at i on

bet ween t he t wo is 1.0 and s uch a cor r el at i on

is si gni f i cant wi t h a p < .001 ( one- t ai l ed)

even whe n onl y fi ve i t ems ar e cor r el at ed. The

modes of t he guesses cor r es pond exact l y wi t h

t he act ual numbe r s of syl l abl es, for t he

val ues one t hr ough t hr ee; for wor ds of f our

and five syl l abl es t he modes cont i nue t o be

t hr ee.

Whe n all TOTs ar e combi ned, t he cont r i -

but i ons t o t he t ot al effect s of i ndi vi dual

Ss a nd of i ndi vi dual wor ds ar e unequal . We

have ma de an anal ys i s i n whi ch each wor d

count s but once. Thi s was accompl i s hed by

cal cul at i ng t he me a n of t he guesses ma de by

al l Ss for whom a pa r t i c ul a r wor d pr eci pi -

t at ed a TOT s t at e and t a ki ng t ha t me a n as

t he score for t ha t wor d. The new me a ns cal -

cul at ed wi t h al l wor ds equal l y wei ght ed wer e,

i n or der : 1. 62; 2. 30; 2. 80; 3. 33; a nd 3. 50.

Thes e val ues ar e cl ose t o t hose of Ta bl e 1

a nd rho wi t h t he act ual numbe r s of syl l abl es

cont i nues t o be 1.0.

We al so ma de a n anal ys i s i n whi ch each S

count s but once. Thi s was done by cal cul at -

i ng t he me a n of a n S's guesses for al l wor ds

3 We ~4sh to t hank Professor Frederick Mostel-

ler for discussing the fragmentary data problem

with us.

"TI P OF THE TONGUE" PHENOMENON 329

TABLE 1

ACTUAL NUMBERS OF SYLLABLES AND GUESSED

NUMBERS FOR ALL TOTs n r aE MA~N EXPERn~E~rr

Guessed numbers No

1 2 3 4 5 guess Mode Mean

1 9 7 1 0 0 0 1 1.53

"~ 2 2 55 22 2 1 5 2 2.33

= 3 3 19 61 10 1 5 3 2.86

=

"d 4 0 2 12 6 2 3 3 3.36

5 0 0 3 0 1 1 3 3.50

of one syllable, the mean for all words of

two syllables, etc. In comparing t he means

of guesses for words of different length one

can only use those Ss who made at least

one guess for each actual length to be

compared. I n the present dat a only words

of two syllables and three syllables pre-

cipitated enough TOTs to yield a sub-

stantial number of such matched scores.

Ther e were 21 Ss who made guesses for bot h

two-syllable and three-syllable words. The

simplest way to evaluate the significance of

the differences in these guesses is with the

Sign Test. I n onl y 6 of 21 mat ched scores

was the mean guess for words of two syl-

lables larger t han t he mean for words of

three syllables. The difference is significant

with a p ~---.039 (one-tailed). For actual

words t hat were only one syllable apart in

length, Ss were able to make a significant

distinction in the correct direction when the

words themselves could not be called to mind.

The 224 SS words and the 95 SM words

provide supporting evidence. Words of sim-

ilar sound (SS) had the same number of

syllables as the t arget in 48% of all cases.

This value is close to the 57% t hat were

correct for explicit guesses in the main ex-

peri ment and still closer to the 4 7 ~ correct

al ready reported for the pretest. The SM

words provide a clear cont rast ; onl y 20%

mat ched the number of syllables in the tar-

~get. We conclude t hat S in a positive TOT

state has a significant ability to recall cor-

rect l y the number of syllables in the word

he is trying to retrieve.

I n Tabl e 1 it can be seen t hat the modes

of guesses exactly correspond with the ac-

tual numbers of syllables in target words for

the values one through three. For still longer

t arget words (four and five syllables) the

means of guesses continue to rise but the

modes st ay at the value three. Words of

more t han three syllables are rare in En-

glish and the generic ent ry for such words

may be the same as for words of three

syllables; something like "t hree or more"

may be used for all long words.

Initial Let t er

Over all positive TOTs, the initial letter

of the word S was seeking was correctly

guessed 57% of the time. The pret est re-

sult was 51% correct. The results from the

main experiment were analyzed with each

word counting just once by entering a word' s

score as "cor r ect " whenever the most com-

mon guess or the onl y guess was in fact

correct; 62% of words were, by this reckon-

ing, correctly guessed. The SS words had

initial letters matching the initial letters of

the t arget words in 49% of all cases. We do

not know the chance level of success for this

performance but with 26 letters and many

words t hat began with uncommon letters

the level must be low. Probabl y the results

for the SM words are bet t er than chance

and yet the outcome for these words was

onl y 8% matches.

We did an analysis of the SS and SM

words, with each S counting j ust once. Ther e

were 26 Ss who had at least one such word.

For each S we calculated the proportion of

SS words matching the t arget in initial letter

and the same proportion for SM words. For

21 Ss t he proportions were not tied and in

all but 3 cases the larger value was t hat of

the SS words. The difference is significant

by Sign Test with p ~--- .001 (one-tailed).

The evidence for significantly accurate

generic recall of inital letters is even stronger

than for syllables. The absolute levels of suc-

cess are similar but the chance baseline

330 BROWN AND MC NEILL

must be much lower for letters than for syl-

lables because the possibilities are more

nume r ous .

Syllabic Stress

We did not ask S to guess the stress pat-

tern of the target word but the SS words

provide relevant data. The test was limited

to the syllabic location of the primary or

heaviest stress for which The American Col-

lege Dictionary was our authority. The num-

ber of SS words that could be used was

limited by three considerations. (a) Words

of one syllable had to be excluded because

there was no possibility of variation. (b)

Stress locations could only be matched if

the SS word had the same number of syl-

lables as the target, and so only such match-

ing words could be used. (c) Invented words

and foreign words could not be used because

they do not appear in the dictionary. Only

49 SS words remained.

As it happened all of the target words in-

volved (whatever their length) placed the

primary stress on either the first or the sec-

ond syllable. It was possible, therefore, to

make a 2 X 2 table for the 49 pairs of tar-

get and SS words which would reveal the

correspondences and noncorrespondences. As

can be seen in Table 2 the SS words tended

to stress the same syllable as the target

words. The X 2 for this table is 10.96 and that

value is significant with p < .001. However,

the data do not meet the independence re-

quirement, so we cannot be sure that the

matching tendency is significant. There

were not enough data to permit any other

analyses, and so we are left suspecting that S

TABLE 2

SYLLABLES RECEIVING PRIIVfARY STRESS IN TARGET

WORDS AND SS WORDS

Target words

1st syllable 2nd syllable

1st syllable 25 6

u~ 2nd syllable 6 12

in a TOT state has knowledge of the stress

pattern of the target, but we are not sure

of it.

Letters in Various Positions

We did not require explicit guesses for let-

ters in positions other than the first, but the

SS words provide relevant data. The test

was limited to the following positions: first,

second, third, third-last, second-last, and last.

A target word must have at least six letters

in order to provide data on the six positions;

it might have any number of letters larger

than six and still provide data for the six

(relatively defined) positions. Accordingly

we included the data for all target words

having six or more letters.

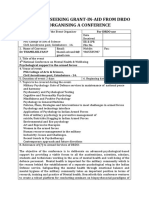

Figure 1 displays the percentages of let-

ters in each of six positions of SS words

which matched the letters in the same posi-

tions of the corresponding targets. For com-

parison purposes these data are also provided

for SM words. The SS curve is at all points

above the SM curve; the two are closest

together at the third-last position. The values

for the last three positions of the SS curve

quite closely match the values for the first

three positions. The values for the last three

positions of the SM curve, on the other hand,

are well above the values for the first three

0.55 -- o==-,o Words s/m//or in sound {SS)

o- - - o Words similar in meon/no($Ml l

0.50 -

-I

0.45 - -

0. 40 - -

0. 35 --

u_

o 0.30 --

~o.2s -

0.20 - . / ", , , , / -

~o.~5 - I -

n- I --

u.J 0.I0 - -----o,, I

n %

0. 05 - ~,,~I - -

o. oo I I T I I I

1st 2 nd 3 rd 3 rd- 2 nd- Last

Last Last

POSI TI ON IN WORD

FIG. 1. Percentages of letter matches between

target words and SS words for six serial positions.

"TIP OF THE TONGUE" PHENOMENON 331

positions. Consequently the relative superior-

ity of the SS curve is greater in the first

three positions.

The letter-position data were also analyzed

in such a way as to count each target word

just once, assigning each position in the tar-

get a single score representing the proportion

of matches across all Ss for that position in

that word. The order of the SS and SM

points is preserved in this finer analysis. We

did Sign Tests comparing the SS and SM

values for each of the six positions. As Fig. 1

would suggest the SS values for the first three

positions all exceeded the SM values with

p' s less than .01 (one-tailed). The SS" values

for the final two positions exceeded the SM

values with p' s less than .05 (one-tailed).

The SS values for the third-last position were

greater than the SM values but not signifi-

cantly so.

The cause of the upswing in the final

three positions of the SM curve may be

some difference in the distribution of in-

formation in early and late positions of En-

glish words. Probably there is less variety

in the later positions. In any case the fact

that the SS curve lies above the SM curve

for the last three positions indicates that S

in a TOT state has knowledge of the target

in addition to his knowledge of English word

structure.

Chunking of Su~xes

The request to S that he guess the initial

letter of the target occasionally elicited a

response of more than one letter; e.g., ex

in the case of extort and con in the case of

convene. This result suggested that some

letter (or phoneme) sequences are stored as

single entries having been "chunked" by long

experience. We made only one test for chunk-

ing and that involved three-letter suffixes.

I t did not often happen that an S produced

an SS word that matched the target with

respect to all of its three last letters. The

question asked of the data was whether

such three-letter matches occurred more often

when the letters constituted an English suffix

than when they did not. In order to deter-

mine which of the target words terminated

in such a suffix, we entered The American

College Dictionary with final trigrams. If

there was an entry describing a suffix ap-

propriate to the grammatical and semantic

properties of the target we considered the

trigram to be a suffix. There were 20 words

that terminated in a suffix, including fawn-

ing, unctuous, and philatelist.

Of 93 SS words produced in response to

a target terminating in a suffix, 30 matched

the target in their final three letters. Of 130

SS words supplied in response to a target

that did not terminate in a suffix only 5

matched the target in their final three let-

ters. The data were also analyzed in a way

that counts each S just once and uses only Ss

who produced SS words in response to both

kinds of target. A Sign Test was made of the

difference between matches of svffixes and

matches of endings that were not suffixes;

the former were more common with p = .059

(one-tailed). A comparable Sign Test for

SM words was very far from significance.

We conclude that suffix-chunking probably

plays a role in generic recall.

Proximity to the Target and Quality of In-

formation

There were three varieties of positive TOT

states: (1) Cases in which S recognized the

word read by E as the word he had been

seeking; (2) Cases in which S recalled the

intended word before it was read out; (3)

Cases in which S recalled the word he had

been seeking before E read the intended

word and the recalled word was not the same

as the word read. Since S in a TOT state of

either type 2 or type 3 reached the target

before the intended word was read and S in

a TOT state of type 1 did not, the TOTs of

the second and third types may be consid-

ered "nearer" the target than TOTs of the

first type. We have no basis for ordering

types 2 and 3 relative t o one another. We

332 B R OWN AND MC NE I L L

predicted t hat Ss in the two kinds of TOT

st at e t hat ended in recall (t ypes 2 and 3)

would produce more accurat e i nformat i on

about the t arget t han Ss in the TOT st at e

t hat ended in recognition ( t ype 1).

The prediction was tested on the explicit

guesses of initial letters since these were the

most complete and sensitive dat a. Ther e

were 138 guesses from Ss in a t ype 1 st at e

and 58 of these, or 4 2 ~ , were correct. There

were 36 guesses from Ss in a t ype 2 st at e

and, of these, 20, or 56%, were correct.

There were 59 guesses from Ss in a t ype 3

st at e and of these 39, or 66%, were correct.

We also anal yzed the results in such a way

as to count each word onl y once. The per-

centages correct were: for t ype i , 50%;

t ype 2, 62%; t ype 3, 63%. Finally, we per-

formed an analysis counting each S j ust once

but averagi ng together t ype 2 and t ype 3

results in order to bri ng a maxi mum number

of Ss into the comparison. The combining

action is justified since bot h t ype 2 and t ype

3 were st at es ending in recall. A Sign Test

of the differences showed t hat guesses were

more accurat e in the st at es t hat ended in

recall t han in the st at es t hat ended in recog-

nition; one-tailed p < .01. Suppl ement ary

analyses with SS and SM words confirmed

these results. We conclude t hat when S is

nearer his t arget his generic recall is more

accurat e t han when he is fart her from the

target.

Special interest at t aches to the results from

t ype 2 TOTs. I n the met hod of our experi-

ment there is nothing to guarant ee t hat when

S said he recognized a word he had real l y

done so. Perhaps when E read out a word, S

could not help thinking t hat t hat was the

word he had in mind. We ourselves do not

believe anyt hi ng of the sort happened. The

single fact t hat most Ss claimed fewer t han

five positive TOTs in a 2-hr period argues

agai nst any such effect. Still it is reassuring

to have the 36 t ype 2 cases in which S re-

called the intended word be]ore it was read.

The fact t hat 56% of the guesses of initial

letters made in t ype 2 st at es were correct is

hard-core evidence of generic recall. I t may

be wort h adding t hat 65% of the guesses

of the number of syllables for t ype 2 cases

were correct .

Judgments o] the Proximity of SS Words

The several comparisons we have made of

SS and SM words demonst rat e t hat when

recall is i mmi nent S can distinguish among

t he words t hat come to mind those t hat re-

semble the t arget in form from those t hat

do not resemble the t arget in form. Ther e

is a second ki nd of evidence which shows

t hat S can tell when he is getting close (or

" wa r m" ) .

I n 15 instances Ss rat ed two or more SS

words for comparat i ve si mi l ari t y to the t ar-

get. Our analysis cont rast s those rat ed "most

si mi l ar" (1) with those rat ed next most

similar (2). Since there were very few words

rat ed (3) we at t empt ed no analysis of t hem.

Similarity poi nt s were given for all the fea-

tures of a word t hat have now been demon-

st rat ed to pl ay a par t in generic r ecal l - - wi t h

the single exception of stress. Stress had to

be disregarded because some of the words

were i nvent ed and their stress pat t er ns were

unknown.

The probl em was to compare pai rs of SS

words, rat ed 1 and 2, for overall si mi l ari t y

to the target. We determined whether each

member mat ched the t arget in number of

syllables. I f one did and the other did not,

then a single si mi l ari t y poi nt was assigned

the word t hat mat ched. For each word, we

counted, beginning wi t h the initial letter,

the number of consecutive letters in common

with the target. The word havi ng the longer

sequence t hat mat ched the t arget earned one

similarity point. An exactly comparabl e pro-

cedure was followed for sequences st art i ng

from the final letter. I n sum, each word in

a pai r could receive from zero to three sim-

i l ari t y points.

We made Sign Test s compari ng the t ot al

scores for words rat ed most like the t arget

"TIP OF THE TONGUE" PHENOMENON 333

(1) and words rated next most like the tar-

get (2). This test was onl y slightly inappro-

priate since only two target words occurred

twice in the set of 15 and only one S re-

peated in the set. Ten of 12 differences were

in the predicted direction and the one-tailed

p = .019. I t is of some interest t hat sim-

ilarity points awarded on the basis of letters

in the middle of the words did not even go

in the right direction. Figure 1 has already

indicated t hat t hey also do not figure in Ss'

j udgment s of the comparat i ve similarity to

the target of pairs of SS words. Our conclu-

sion is t hat S at a given distance from the

target can accurat el y judge which of two

words t hat come to mind is more like the

target and t hat he does so in terms of the

features of words t hat appear in generic

recall.

Conclusions

When complete recall of a word has not

occurred but is felt to be imminent there is

likely to be accurate generic recall. Generic

recall of the abstract ]orm vari et y is evi-

denced by S' s knowledge of the number of

syllables in the target and of the location

of the pri mary stress. Generic recall of the

partial vari et y is evidenced by S' s knowledge

of letters in the t arget word. This knowledge

shows a bowed serial-position effect since

it is better for the ends of a word t han for

the middle and somewhat better for begin-

ning positions t han for final positions. The

accuracy of generic recall is greater when S

is near the target (complete recall is im-

minent) t han when S is far from the target.

A person experiencing generic recall is able

to judge the relative similarity to the target

of words t hat occur to hi m and these judg-

ments are based on the features of words

t hat figure in partial and abst ract form re-

call.

DISCUSSION

The facts of generic recall are relevant to

theories of speech perception, reading, the

understanding of sentences, and the organiza-

tion of memory. We have not worked out alI

the implications. I n this section we first at-

t empt a model of the TOT process and then

t ry to account for the existence of generic

memory.

A Model of the Process

Let us suppose (with Kat z and Fodor,

1963, and many others) t hat our long-term

memory for words and definitions is organ-

ized into the functional equivalent of a dic-

tionary. I n real dictionaries, those t hat are

books, entries are ordered alphabetically

and bound in place. Such an arrangement is

too simple and too inflexible to serve as a

model for a mental dictionary. We will sup-

pose t hat words are entered on keysort cards

instead of pages and t hat the car ds are

punched for various features of ".he words

entered. Wi t h real cards, paper ones, it is

possible to retrieve from the total deck any

subset punched for a common feature by

put t i ng a metal rod t hrough the proper hole.

We will suppose t hat there is in the mi nd

some speedier equivalent of this retrieval

technique.

The model will be described in terms of a single

example. When the target word was sextant, Ss

heard the definition: "A navigational instrument

used in measuring angular distances, especially the

altitude of sun, moon, and stars at sea." This deft-

nifion precipitated a TOT state in 9 Ss of the total

56. The SM words included: astrolabe, compass,

dividers, and protractor. The SS words included:

secant, sextet, and sexton.

The problem begins with a definition rather than

a word and so S must enter his dictionary back-

wards, or in a way that would be backwards and

quite impossible for the dictionary that is a book.

It is not impossible with keysort cards, providing

we suppose that the cards are punched for some

set of semantic features. Perhaps these are the

semantic "markers" that Katz and Fodor (1963)

postulate in their account of the comprehensioh of

sentences. We will imagine that it is somehow pos-

sible to extract from the definition a set of markers

and that these are, in the present case: "navigation,

instrument, having to do with geometry." Metal

rods thrust into the holes for each of these features

might fish up such a collection of entries as: astro-

labe, compass, dividers, and protractor. This first

334 BROWN AND MC NEI LL

~et ri eval , whi c h is i n r es pons e t o t he def i ni t i on,

mu s t be s emant i cal l y ba s e d a n d i t will not , t her ef or e,

a c c ount / or t he a ppe a r a nc e of s uc h SS wor ds as

sextet a nd sexton.

The r e ar e f our ma j o r ki nds of out c ome of t he

first r et r i eval a n d t hes e out c ome s c or r e s pond wi t h

t he f our ma i n t hi ngs t h a t h a p p e n to Ss i n t he "TOT

exper i ment . We will a s s u me t h a t a def i ni t i on of each

wor d r et r i eved is ent er ed on i t s car d a n d t h a t i t i s

possi bl e to check t he i n p u t def i ni t i on a ga i ns t t hos e

on t he car ds. Th e fi rst possi bl e out c ome i s t h a t

sextant is r et r i eved al ong wi t h compass a n d astro-

labe a n d t he ot he r s a n d t h a t t he def i ni t i ons ar e

specific e nough so t h a t t he one ent er ed f or sextant

r egi st er s as ma t c h i n g t he i n p u t a n d al l t he ot he r s

as n o t - ma t c h i n g . Thi s is t he case of cor r ect r ecal l ;

S h a s f o u n d a wo r d t h a t ma t c he s t he def i ni t i on a n d

i t is t he i nt e nde d wor d. The s econd possi bi l i t y is

t h a t sextant is n o t a mo n g t he wor ds r et r i eved a nd,

i n addi t i on, t he def i ni t i ons ent er ed f or t hos e r e-

t r i eved ar e so i mpr eci se t h a t one of t h e m ( t he

def i ni t i on f or compass, f or exampl e) r egi st er s as

ma t c h i n g t he i nput . I n t hi s case S t hi nks he ha s

f o u n d t he t ar get t h o u g h he real l y has not . Th e

t hi r d possi bi l i t y is t h a t sextant is n o t a mo n g t he

wor ds r et r i eved, b u t t he def i ni t i ons ent er ed f or t hos e

r et r i eved ar e specific e nough so t h a t none of t h e m

will r e ~s t e r a ma t c h wi t h t he i nput . I n t hi s case, S

does n o t k n o w t he wo r d a n d real i zes t he f act . Th e

a bove t hr ee out c ome s ar e t he c o mmo n ones a n d

none of t h e m r epr es ent s a T OT s t at e.

I n t he TOT case t he f i r st r et r i eval mu s t i ncl ude a

car d wi t h t he def i ni t i on of sextant ent er ed on i t

b u t wi t h t he wo r d i t sel f i ncompl et el y ent er ed. Th e

car d mi ght , for i ns t ance, ha ve t he f ol l owi ng i n-

f or ma t i on a b o u t t he wor d: t wo- s yl l abl es , i ni t i al s,

fi nal t. The e n t r y wo u l d be a p u n c h c a r d e qui va l e nt

of S _ _ _ _ T . Pe r ha ps a n i nc ompl e t e e n t r y of t hi s

s or t is J a me s ' s " s i ngul ar l y def i ni t e ga p" a n d t he

basi s f or gener i c recall.

The S wi t h a cor r ect def i ni t i on, ma t c h i n g t he i n-

put , a n d a n i ncompl et e wo r d e nt r y wi l l k n o w t h a t

he k n o ws t he wor d, will feel t h a t he a l mos t h a s i t ,

t h a t i t is on t he t i p of hi s t ongue. I f he is a s ke d

t o gues s t he n u mb e r of syl l abl es a n d t he i ni t i al

l et t er he s houl d, in t he case we h a v e i magi ned, be

abl e to do so. He s houl d al so be abl e to pr oduce SS

wor ds. The f eat ur es t h a t a ppe a r i n t he i nc ompl e t e

e n t r y ( t wo- s yl l abl es , i ni t i al s, a n d fi nal t ) can be

us ed as t he basi s f or a s econd r et r i eval . Th e s ubs e t

of car ds def i ned by t he i nt er s ect i on of al l t hr ee

f eat ur es wo u l d i ncl ude car ds f or secant a n d sextet.

I f one f e a t ur e wer e n o t us e d t h e n sexton woul d be

a dde d t o t he set .

Whi c h of t he f act s a b o u t t he TOT s t at e can n o w

be a c c ount e d f or ? We k n o w t h a t Ss wer e abl e, wh e n

t he y h a d not r ecal l ed a t ar get , t o di s t i ngui s h be-

t ween wor ds r es embl i ng t he t a r ge t i n s o u n d (SS

wor ds ) a n d wor ds r es embl i ng t he t a r ge t i n me a n i n g

onl y ( SM wor ds ) . Th e basi s f or t hi s di s t i nct i on i n

t he model woul d seem to be t he di s t i nct i on bet ween

t he fi rst a n d s econd r et r i eval s. Me mb e r s h i p i n t he

fi rst s ubs e t r et r i eved defi nes SM wor ds a n d me m-

ber s hi p i n t he s econd s ubs e t def i nes SS wor ds .

We k n o w t h a t wh e n S h a d pr oduc e d sever al SS

wor ds b u t h a d n o t recal l ed t he t a r ge t he coul d

s ome t i me s accur at el y r a nk- or de r t he SS wor ds f or

s i mi l ar i t y to t he t ar get . Th e model offers a n a c c ount

of t hi s r a nki ng pe r f or ma nc e . I f t he i ncompl et e e n t r y

f or sextant i ncl udes t hr ee f eat ur es of t he wo r d t he n

SS wor ds h a v i n g onl y one or t wo of t hes e f e a t ur e s

(e.g., sexton) s houl d be j udge d less si mi l ar t o t he

t ar get t h a n SS wor ds h a v i n g al l t hr ee of t h e m

(e.g., secant).

Wh e n a n SS wo r d ha s al l of t he f eat ur es of t he

i ncompl et e e n t r y (as do secant a n d sextet i n our

exampl e) wh a t pr e ve nt s i t s bei ng mi s t a ke n f or t he

t a r ge t ? Wh y di d n o t t he S who pr oduc e d sextet

t h i n k t h a t t he wo r d wa s " r i g h t ? " Becaus e of t he

def i ni t i ons. Th e f or ms me e t al l t he r e qui r e me nt s of

t he i ncompl et e e n t r y b u t t he def i ni t i ons do not

ma t c h.

Th e TOT s t a t e of t en ended i n r e c ogni t i on; i.e.,

S fai l ed to recall t he wo r d b u t wh e n E r e a d o u t

sextant S r ecogni zed i t as t he wo r d he h a d been

seeki ng. The mode l a c c ount s f or t hi s out c ome as

f ol l ows. Suppos e t h a t t her e is onl y t he i nc ompl e t e

e n t r y S____. T i n me mo r y , pl us t he def i ni t i on. Th e

E n o w s a ys ( i n effect ) t h a t t her e exi st s a wo r d

sextant whi c h has t he def i ni t i on i n ques t i on. Th e

wo r d sextant t he n sat i sfi es al l t he da t a poi nt s avai l -

abl e to S; i t ha s t he f i ght n u mb e r of syl l abl es, t he

r i ght i ni t i al l et t er , t he r i ght fi nal l et t er , a n d i t is

sai d to h a v e t he r i ght def i ni t i on. The r es ul t is r ecog-

ni t i on.

Th e pr opos e d a c c ount ha s s ome t es t abl e i mpl i ca-

t i ons. Suppos e t h a t F. wer e t o r e a d out , wh e n r e-

call fai l ed, n o t t he cor r ect wo r d sextant b u t a n

i n v e n t e d wo r d like sekrant or saktint whi c h s at i s -

fies t he i ncompl et e e n t r y as wel l as does sextant

i t sel f. I f S h a d n o t h i n g b u t t he i ncompl et e e n t r y a n d

E' s t e s t i mony to gui de h i m t he n he s houl d " r ecog-

ni ze" t he i nve nt e d wo r d s j u s t as he r ecogni zes

sextant.

Th e a c c ount we h a v e gi ven does n o t accor d wi t h

i nt ui t i on. Our i nt ui t i ve not i on of r ecogni t i on i s

t h a t t he f eat ur es whi c h coul d not be cal l ed wer e

act ual l y i n s t or age b u t less accessi bl e t h a n t he f ea-

t ur es t h a t wer e recal l ed. To s t a y wi t h our exampl e,

i nt ui t i on s ugges t s t h a t t he f eat ur es of sextant t h a t

coul d n o t be recal l ed, t he l et t er s be t we e n t he f i r st

a n d t he l ast , wer e ent er ed on t he c a r d b u t wer e

~TIP OF THE TONGUE '~ PHENOMENON 335

less "legible" than the recalled features. We might

imagine them printed in small letters and faintly.

When, however, the g reads out the word sextant,

then S can make out the less legible parts of his

entry and, since the total entry matches E' s word, S

recognizes it. This sort of recognition should be

"t i ght er" than the one described previously. Sekrant

and saktint would he rejected.

We did not try the effect of invented words and

we do not know how they would have been re-

ceived hut among the outcomes of the actual ex-

periment there is one t hat strongly favors the

faint-entry theory. Subjects in a TOT state, after

all, sometimes recalled the target word wi t hout any

prompting. The incomplete entry theory does not

admit of such a possibility. I f we suppose t hat the

ent ry is not S_____T but something more like

Sex tanT (with the italicized lower-case letters rep-

resenting the faint-entry section) we must still

explain how i t happens t hat the faintly entered,

and at first inaccessible, middle letters are made

accessible in the case of recall.

Perhaps it works something like this. The fea-

tures that are first recalled operate as we have

suggested, to retrieve a set of SS wo.rds. Whenever

an SS word (such as secant) includes middle letters

that are matched in the faintly entered section of

the target then those faintly entered letters become

accessible. The match brings out the missing parts

the way heat brings out anything written in lemon

juice. In other words, when secant is retrieved the

target entry grows from Sex tanT to SEx rANT.

The retrieval of sextet brings out the remaining

letters and S recalls the complete word--sextant.

I t is now possible to explain the one as yet un-

explained outcome of the TOT experiment. Subjects

whose state ended in recall had, before they found

the target, more correct information about i t than

did Ss whose state ended in recognition. More cor-

rect information means fewer features to be brought

out by duplication in SS words and so should mean

a greater likelihood that all essential features will

be brought out in a short period of time.

All of the above assumes that each word is en-

tered in memory just once, on a single card. There

is another possibility. Suppose that there are entries

for sextant on several different cards. They might

all be incomplete, but at different points, or, some

might be incomplete and one or more of them com-

plete. The several cards woul d be punched for

different semantic markers and perhaps for different

associations so t hat the entry recovered would

vary with the rule of retrieval. With this concep-

tion we do not require the notion of faint entry.

The difference between features commonly recalled,

such as the first and last letters, and features that

are recalled with difficulty or perhaps only recog-

nized, can be rendered in another way. The more

accessible features are entered on more cards or

else the cards on which they appear are punched

for more markers; in effect, they are wired into

a more extended associative net.

The Reason ]or Generic Recall

I n a d u l t mi n d s wo r d s a r e s t o r e d i n b o t h

vi s ua l a nd a u d i t o r y t e r ms a n d b e t we e n t he

t wo t h e r e a r e c o mp l i c a t e d r ul es of t r a ns l a -

t i on. Ge n e r i c r e c a l l i n v o l v e s l e t t e r s ( or pho-

n e me s ) , affi xes, s yl l abl es , a n d s t r es s l oc a t i on.

I n t hi s s e c t i on we wi l l di s cus s o n l y l e t t e r s

( l e gi bl e f o r ms ) a nd wi l l a t t e mp t t o e xpl a i n

a s i ngl e e f f e c t - - t h e s er i al pos i t i on ef f ect i n

t he r e c a l l of l et t er s . I t is n o t c l e a r h o w f a r

t he e x p l a n a t i o n c a n be e xt e nde d.

I n br i e f o v e r v i e w t hi s i s t he a r g u me n t .

T h e de s i gn of t he En g l i s h l a n g u a g e is s uc h

t h a t one wo r d is us ua l l y d i s t i n g u i s h e d f r o m

al l o t h e r s i n a mo r e - t h a n - mi n i ma l wa y, i . e. ,

b y mo r e t h a n a s i ngl e l e t t e r i n a s i ngl e pos i -

t i on. I t is c o n s e q u e n t l y possible t o r e c ogni z e

wo r d s wh e n one ha s n o t s t or e d t he c o mp l e t e

l e t t e r s e que nc e . T h e e v i d e n c e i s t h a t we do

n o t s t or e t he c o mp l e t e s e q u e n c e i f we do n o t

h a v e t o. We be gi n b y a t t e n d i n g c hi e f l y t o

i ni t i a l a nd f i nal l e t t e r s a n d s t or i ng t hes e.

T h e o r d e r of a t t e n t i o n a n d of s t or a ge f a vor s

t he ends of wo r d s be c a us e t he e nds c a r r y

mor e i n f o r ma t i o n t h a n t h e mi ddl e s . An i n-

c o mp l e t e e n t r y wi l l s e r ve f or r e c ogni t i on, b u t

i f wor ds a r e t o be p r o d u c e d ( or r e c a l l e d)

t h e y mu s t be s t or e d i n ful l . F o r mo s t wor ds ,

t hen, i t is e v e n t u a l l y n e c e s s a r y t o a t t e n d t o

t he mi d d l e l et t er s . Si nce e nd l e t t e r s h a v e

be e n a t t e n d e d t o f r om t he f i r st t h e y s houl d

a l wa ys be mor e c l e a r l y e n t e r e d or mo r e

e l a b o r a t e l y c o n n e c t e d t h a n mi d d l e l et t er s .

Wh e n r ecal l is r e qui r e d, of wor ds t h a t a r e

n o t v e r y f a mi l i a r t o S, as i t wa s i n our ex-

p e r i me n t , t h e e nd l e t t e r s s houl d o f t e n be

acces s i bl e wh e n t he mi d d l e a r e not .

I n b u i l d i n g p r o n o u n c e a b l e s e que nc e s t h e

En g l i s h l a ngua ge , l i ke al l o t h e r l a ngua ge s ,

ut i l i zes o n l y a s ma l l f r a c t i o n of i t s c o m-

b i n a t o r i a l pos s i bi l i t i e s ( Ho c k e t t , 1958) . I f

336 BROWN AND MC NEILL

a l anguage used all possi bl e sequences of

phonemes (or l et t er s) its wor ds coul d be

short er, but t hey woul d be much mor e vul -

ner abl e to mi sconst r uct i on. A change of any

si ngl e l et t er woul d r esul t in r ecept i on of a

di fferent word. As mat t er s ar e act ual l y ar-

r anged, most changes r esul t in no wor d at

al l ; for exampl e: textant, sixtant, sektant.

Our wor ds ar e hi ghl y r edundant and fai rl y

i ndest r uct i bl e.

Under wood ( 1963) has made a di st i nct i on

for t he l ear ni ng of nonsense syl l abl es be-

t ween t he " nomi na l " st i mul us whi ch is t he

syl l abl e pr esent ed and t he " f unct i onal " st i m-

ul us whi ch is t he set of char act er i st i cs of t he

syl l abl e act ual l y used t o cue t he response.

Under wood r evi ews evi dence showi ng t hat

col l ege st udent s l ear ni ng pai r ed- associ at es do

not l ear n any mor e of a st i mul us t r i gr am

t han t hey have to. If, for i nst ance, each of

a set of st i mul us t r i gr ams has a di fferent

i ni t i al l et t er, t hen Ss ar e not l i kel y to l ear n

l et t ers ot her t han t he first, si nce t hey do

not need t hem.

Fei genbaum ( 1963) has wr i t t en a com-

put er pr ogr am ( EPAM) whi ch si mul at es

t he sel ect i ve- at t ent i on aspect of ver bal l ear n-

i ng as wel l as many ot her aspect s. " . . .

EPAM has a noticing order ]or letters of

syllables, whi ch prescri bes at any moment a

l et t er - scanni ng sequence for t he mat chi ng

process. Because i t is obser ved t hat subj ect s

gener al l y consi der end l et t er s bef or e mi ddl e

l et t ers, t he not i ci ng or der is i ni t i al i zed as

fol l ows: first l et t er, t hi r d l et t er , second l et -

t er " (p. 304) . We bel i eve t hat t he di fferen-

t i al recal l of l et t er s in var i ous posi t i ons, re-

veal ed in Fi g. 1 of t hi s paper , is t o be

expl ai ned by t he oper at i on in t he per cept i on

of real wor ds of a rul e ver y much l i ke Fei gen-

baum' s.

Feigenbaum's EPAM is so written as to make

it possible for the noticing rule to be changed by

experience. If the middle position Were consistently

the position that differentiated syllables, the com-

puter would learn to look there first. We suggest

that the human tendency to look first at the begin-

ning of a word, then at the end and finally the

middle has "grown" in response to the distribu-

tion of information in words. Miller and Friedman

(1957) asked English speakers to guess letters for

various open positions in segments of English text

that were 5, 7, or 11 characters long: The percent-

ages of correct first guesses show a very clear serial

position effect for segments of all three lengths.

Success was lowest in the early positions, next

lowest in the final positions, and at a maximum in

the middle positions. Therefore, information was

greatest at the start of a word, next greatest at the

end, and least in the middle. Attention needs to be

turned where information is, to the parts of the

word that cannot be guessed. The Miller and Fried-

man segments did not necessarily break at word

boundaries but their discovery that the middle

positions of continuous text are more easily guessed

than the ends applies to words.

Is there any evidence that speakers of English do

attend first to the ends of English words? There is

no evidence that the eye fixations of adult readers

consistently favor particular parts of words (Wood-

worth and Schlosberg, 1954). However, it is not

eye fixation that we have in mind. A considerable

stretch of text can be taken in from a single fixa-

tion point. We are suggesting that there is selection

within this stretch, selection accomplished centrally;

perhaps by a mechanism like Broadbent's (1958)

"biased filter."

Bruner and O' Dowd (1958) studied word per-

ception with tachistoscopic exposures too brief to

permit more than one fixation. In each word pre-

sented there was a single reversal of two letters and

the S knew this. His task was to identify the

actual English word responding as quickly as pos-

sible. When the actual word was AVIATION, Ss

were presented with one of the following: VAIA-

TION, AVITAION, AVIATINO. Identification of

the actual word as AVIATION was best when S

saw AVITAION, next best when he saw AVIA-

TINO, and most difficult when he saw VAIATION.

In general, a reversal of the two initial letters made

identification most difficult, reversal of the last two

letters made it somewhat less difficult, reversal in

the middle made least difficulty. This is what should

happen if words are first scanned initially, then

finally, then medially. But the scanning cannot be

a matter of eye movements; it must be more central.

Selective attention to the ends of words should

lead to the entry of these parts into the mental

dictionary, in advance of the middle parts. However,

we ordinarily need to know more than the ends

of words. Underwood has pointed out (1963), in

connection with paired-associate learning, that

while partial knowledge may be enough for a stim-

ulus syllable which need only be recognized it will

~TIP OF THE TONGUE" PHENOMENON 337

not suffice for a response item which must be

produced. The case is simi!ar for natural language.

In order to speak one must know all of a word.

However, the words of the present study were low-

frequency words, words likely to be in the passive

or recognition vocabularies of the college-student Ss

but not in their active vocabularies; stimulus items,

in effect, rather than response items. If knowledge

of the parts of new words begins at the ends and

moves toward the middle we might expect a word

like numismatics, which was on our list, to be still

registered as NUM____I CS. Reduced entries of

this sort would in many contexts serve to retrieve

the definition.

The argument is reinforced by a well-known

effect in spelling. Jensen (1962) has analyzed

thousands of spelling errors for words of 7, 9,

or 11 letters made by children in the eighth and

tenth grades and by junior college freshmen. A

striking serial position effect appears in all his sets

of data such that errors are most common in the

middle of the word, next most common at the end,

and least common at the start. These results are as

they should be if the order of attention and entry

of information is first, last, and then, middle. Jen-

sen's results show us what happens when children

are forced to produce words that are still on the

recognition level. His results remind us of those

bluebooks in which students who are uncertain of

the spelling of a word write the first and last let-

ters with great clarity and fill in the middle with

indecipherable squiggles. That is what should hap-

pen when a word that can be only partially re-

called must be produced in its entirety. End letters

and a stretch of squiggles may, however, be quite

adequate for recognition purposes. In the TOT

experiment we have perhaps p!aced adult Ss in a

situation comparable to that created for children by

Jensen' s spelling tests.

T h e r e a r e t wo p o i n t s t o c l a r i f y a n d t he

a r g u me n t i s f i ni s hed. T h e Ss i n our e xpe r i -

me n t we r e col l ege s t ude nt s , a n d so i n o r d e r

t o o b t a i n wo r d s on t he ma r g i n of k n o wl e d g e

we h a d t o us e wo r d s t h a t a r e v e r y i n f r e q u e n t

i n En g l i s h as a whol e. I t is n o t our t h o u g h t ,

h o we v e r , t h a t t he T OT p h e n o me n o n oc c ur s

o n l y wi t h r a r e wor ds . T h e a b s o l u t e l o c a t i o n

of t h e ma r g i n of wo r d k n o wl e d g e is a f unc -

t i on of S' s a ge a n d e duc a t i on, a n d so wi t h

o t h e r Ss we wo u l d e x p e c t t o o b t a i n T OT

s t a t e s f or wo r d s mo r e f r e q u e n t i n Engl i s h.

F i n a l l y t h e ne e d t o p r o d u c e ( or r e c a l l ) a

wo r d is n o t t he o n l y f a c t or t h a t is ] i kel y t o

e n c o u r a g e r e g i s t r a t i o n of i t s mi d d l e l et t er s .

T h e a mo u n t of de t a i l ne e de d t o s pe c i f y a

wor d u n i q u e l y mu s t i nc r e a s e wi t h t h e t ot a l

n u mb e r of wo r d s k n o wn , t he n u mb e r f r o m

whi c h a n y one i s t o be di s t i ngui s he d. Cons e -

q u e n t l y t he g r o wt h of v o c a b u l a r y , as wel l as

t h e ne e d t o r ecal l , s houl d h a v e s ome p o we r

t o f or ce a t t e n t i o n i nt o t he mi d d l e of a wor d.

R E F E R E N C E S

BARNIIART, C. L. (Ed.) The American college dic-

tionary. New York: Harper, 1948.

BROADBENT, D. E. Perception and communication.

New York: Macmillan, 1958.

BRUNER, J. S., AND O'DowD, D. A note on the in-

formativeness of words. Language and Speech,

1958, 1, 98-101.

FEICENBAU~t, E. A. The simulation of verbal learn-

ing behavior. In E. A. Feigenbaum and J. Feld-

man (Eds.) Computers and thought. New York:

McGraw-Hill, 1963. Pp. 297-309.

HOCI~ETT, C. F. A course in modern linguistics. New

York: Macmillan, 1958.

J A~S, W. The principles of psychology, Vol. I.

New York: Holt, 1893.

JENSE~, A. R. Spelling errors and the serial-position

effect. J. educ. Psychol., 1962, 53, 105-109.

KATZ, J. J., AND FODOR, J. A. The structure of a

semantic theory. Language, 1963, 39, 170-210.

M I L L E R , G. A., A N D FRIEDI~AN, E L I Z A B E T H A. T h e

reconstruction of mutilated English texts. In-

lOTto. Control, 1957, 1, 38-55.

THORN'DIKE, E. L., AND LORGE, I. The teacher's word

book o] 30,000 words. New York: Columbia

Univer., 1952.

UNDERWOOD, B. J. Stimulus selection in verbal

learning. In C. N. Corer and B. S. Musgrave

(Eds.) Verbal behavior and learning: problems

and processes. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1963.

Pp. 33-48.

WENZL, A. Empirische und theoretische Beitriige

zur Erinnerungsarbeit bei erschwerter Wort -

findung. Arch. ges. Psychol., 1932, 85, 181-218.

WENZL, A. Empirische und theoretische Beitr~ge

zur Erinnerungsarbeit bei erschwerter Wort -

findung. Arch. ges. Psychol., 1936, 97, 294-318.

WOODWORTI~, R. S. Psychology. (3rd ed.). New York:

Holt, 1934.

WOODWORTICI, R. S., A-~'D SCIILOSBERG, H. Experi-

mental psychology. (Rev. ed.). New York:

Holt, 1954.

(Received January 15, 1965)

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Psychiatry Image BankDocumento117 paginePsychiatry Image BankSameeksha DasNessuna valutazione finora

- Rosicrucian Digest, March 1942Documento44 pagineRosicrucian Digest, March 1942sauron385100% (2)

- Resilience PDFDocumento9 pagineResilience PDFiammikemills100% (1)

- Netflix Pitch Workshop PDFDocumento27 pagineNetflix Pitch Workshop PDFAlok nr100% (10)

- BOTA Sound and Color 1931Documento31 pagineBOTA Sound and Color 1931Anonymous71% (7)

- Lakoff, Robin Language and Womans PlaceDocumento46 pagineLakoff, Robin Language and Womans PlaceCarolina Mendes Soares100% (1)

- Watchtower: Kingdom Ministry, 1965 IssuesDocumento52 pagineWatchtower: Kingdom Ministry, 1965 Issuessirjsslut100% (1)

- Lessons in Zulu 1000229524 PDFDocumento137 pagineLessons in Zulu 1000229524 PDFDarionWestNessuna valutazione finora

- Personal Development 11: Katipunan, Buruanga, Aklan Third Periodic Examination-Second Semester A.Y: 2018-2019Documento3 paginePersonal Development 11: Katipunan, Buruanga, Aklan Third Periodic Examination-Second Semester A.Y: 2018-2019M3xobNessuna valutazione finora

- Pamantasan NG Lungsod NG Maynila College of Architecture and Urban PlanningDocumento18 paginePamantasan NG Lungsod NG Maynila College of Architecture and Urban PlanningAL HAYUDININessuna valutazione finora

- Correlation Of: ColorDocumento31 pagineCorrelation Of: ColorMithrasNessuna valutazione finora

- 105 African Proverbs and Wise SayingsDocumento8 pagine105 African Proverbs and Wise SayingsVictor YAKUBU71% (7)

- Smalley - Defining Timbre, Refining Timbre - 1994 - Contemporary Music ReviewDocumento14 pagineSmalley - Defining Timbre, Refining Timbre - 1994 - Contemporary Music Reviewricardo_thomasiNessuna valutazione finora

- Pragmatics - NotesDocumento20 paginePragmatics - NotesJohnny BoczarNessuna valutazione finora

- RationaleDocumento4 pagineRationaleAutentico Justine JoyNessuna valutazione finora

- English4 Q1 DLP Week1 Parts-of-a-Simple-ParagraphDocumento7 pagineEnglish4 Q1 DLP Week1 Parts-of-a-Simple-ParagraphCheryl Amor100% (2)

- Aryan Roots in Chinese .: Ede - InsDocumento6 pagineAryan Roots in Chinese .: Ede - InsMario GriffinNessuna valutazione finora

- Language and Woman 039 S PlaceDocumento92 pagineLanguage and Woman 039 S PlaceMB100% (1)

- Oral Diagnosis: A Handbook of Modern Diagnostic Techniques Used to Investigate Clinical Problems in DentistryDa EverandOral Diagnosis: A Handbook of Modern Diagnostic Techniques Used to Investigate Clinical Problems in DentistryValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5)

- Overcoming Difficulties in Translating Idioms From English Into ArabicDocumento16 pagineOvercoming Difficulties in Translating Idioms From English Into ArabicpatitentNessuna valutazione finora

- Estienne Translation PDFDocumento16 pagineEstienne Translation PDFYoandyCabrera100% (1)

- The Tip of The Tongue Phenomenon (1966) Roger Et AlDocumento13 pagineThe Tip of The Tongue Phenomenon (1966) Roger Et AlSouranil PaulNessuna valutazione finora

- Phonology Home Work #1Documento8 paginePhonology Home Work #1Justin JonesNessuna valutazione finora

- Twenty Five Years of Peace Research-Ten Challenges and Some ResponsesDocumento48 pagineTwenty Five Years of Peace Research-Ten Challenges and Some ResponsesgabrielaNessuna valutazione finora

- Manual de Cátedra Contenidos Teóricos 2022 Comisiones B, C y EDocumento187 pagineManual de Cátedra Contenidos Teóricos 2022 Comisiones B, C y ECeleste EizmendiNessuna valutazione finora

- b14258845 PDFDocumento120 pagineb14258845 PDFRahul AkashNessuna valutazione finora

- ThePronunciationofStandardEnglishinAmerica 10082427Documento252 pagineThePronunciationofStandardEnglishinAmerica 10082427English Kids SchoolNessuna valutazione finora

- 1.new Work For A Theory of Universals PDFDocumento36 pagine1.new Work For A Theory of Universals PDFconlabocallenadetierraNessuna valutazione finora

- A Multilevel Approach in The Study of Talk - In.InteractioniDocumento20 pagineA Multilevel Approach in The Study of Talk - In.InteractioniCarla PomaricoNessuna valutazione finora

- Lewis Putnams ParadoxDocumento17 pagineLewis Putnams ParadoxcgovicencioNessuna valutazione finora

- PDF Hosted at The Radboud Repository of The Radboud University NijmegenDocumento4 paginePDF Hosted at The Radboud Repository of The Radboud University NijmegenthumperwardNessuna valutazione finora

- Erving Goffman - The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life - Communication Out of CharacterDocumento25 pagineErving Goffman - The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life - Communication Out of Characterjelena063fmNessuna valutazione finora

- Roellig The Phoenician Language 1983Documento11 pagineRoellig The Phoenician Language 1983Aek AlgerNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To Legal EnglishDocumento53 pagineIntroduction To Legal Englishanon_219125703Nessuna valutazione finora

- Hill Newsletter Session 1Documento5 pagineHill Newsletter Session 1Marisa Ruth HillNessuna valutazione finora

- Ubc - 1969 - A8 W45 PDFDocumento260 pagineUbc - 1969 - A8 W45 PDFDonpedro AniNessuna valutazione finora

- Fletcher, C. R. (1981) - Short Term Memory Processes in Text Comprehension. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 20 (5), 564-574.Documento11 pagineFletcher, C. R. (1981) - Short Term Memory Processes in Text Comprehension. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 20 (5), 564-574.Juan Satt RománNessuna valutazione finora

- Gianneti - Understanding Movies ProxemicsDocumento16 pagineGianneti - Understanding Movies ProxemicsVauneen PretoriusNessuna valutazione finora

- Mattison - Beatitudes and Moral Theology - Virtue Ethics Approach (2013)Documento31 pagineMattison - Beatitudes and Moral Theology - Virtue Ethics Approach (2013)P. José María Antón, L.C.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ubc - 1969 - A8 K45Documento126 pagineUbc - 1969 - A8 K45Drita MorinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Students FCE Word Formation BookletDocumento35 pagineStudents FCE Word Formation BookletCatalina GonzálezNessuna valutazione finora

- 1986 Adriaens Linguistics PDFDocumento315 pagine1986 Adriaens Linguistics PDFAirra Mae DacutNessuna valutazione finora

- Students Book - Cap 6Documento12 pagineStudents Book - Cap 6Cris SouzaNessuna valutazione finora

- Forst, On The Concept of Justification Narrative-CopiarDocumento13 pagineForst, On The Concept of Justification Narrative-CopiarAntonio Bentura AguilarNessuna valutazione finora

- Forst para Topico de GustavoDocumento31 pagineForst para Topico de GustavoAntonio Bentura AguilarNessuna valutazione finora

- M. B. Emeneau - Sanskrit Sandhi and Exercises-University of California Press (2020)Documento35 pagineM. B. Emeneau - Sanskrit Sandhi and Exercises-University of California Press (2020)Secretario EEFFTONessuna valutazione finora

- Architectural Design 3 - Lecture 2 - ProxemicsDocumento17 pagineArchitectural Design 3 - Lecture 2 - ProxemicsBrigitte ParagasNessuna valutazione finora

- The When, Why and How Of: AttributionDocumento19 pagineThe When, Why and How Of: AttributionMichael AndersonNessuna valutazione finora

- Primary and Secondary NarcissismDocumento8 paginePrimary and Secondary Narcissismv pNessuna valutazione finora

- Published Online by Cambridge University PressDocumento1 paginaPublished Online by Cambridge University PressPolanskyoso o.O Polanskyoso o.O (Polanskyoso o.O)Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Dulce Book BrantonDocumento299 pagineThe Dulce Book BrantonsisNessuna valutazione finora

- HOCHSCHILD - The Capacity To FeelDocumento13 pagineHOCHSCHILD - The Capacity To Feelmyatan666Nessuna valutazione finora

- Pandemonium: A Paradigm For Learning - SelfridgeDocumento22 paginePandemonium: A Paradigm For Learning - SelfridgeWagner Soares100% (1)

- Martinius - YhertioDocumento10 pagineMartinius - YhertioCosmin DuducNessuna valutazione finora

- The Other Face of America-A True Story - by Pino Lo PortoDocumento138 pagineThe Other Face of America-A True Story - by Pino Lo PortoadavielchiùNessuna valutazione finora

- Letter and Word Perception: Orthographic Structure and Visual Processing in ReadingDa EverandLetter and Word Perception: Orthographic Structure and Visual Processing in ReadingNessuna valutazione finora

- Family Resemblance and Rule Governed Behaviour HuffDocumento23 pagineFamily Resemblance and Rule Governed Behaviour HuffGustavo ArroyoNessuna valutazione finora

- Biletzki A - Is There A History of PragmaticsDocumento16 pagineBiletzki A - Is There A History of Pragmaticsdida13Nessuna valutazione finora

- TheJourneyoftheSoulandtheEtherealWorld 10044950Documento189 pagineTheJourneyoftheSoulandtheEtherealWorld 10044950gayathrisai2997Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Dystonaut: Digital Version AvailableDocumento8 pagineThe Dystonaut: Digital Version Availablemaruka33Nessuna valutazione finora

- TEORIAS DE LA VERDAD SIGLO XX 1-With-Cover-Page-V2Documento45 pagineTEORIAS DE LA VERDAD SIGLO XX 1-With-Cover-Page-V2Lucia RojasNessuna valutazione finora