Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Angiogranuloma Gingivaj.1834 7819.2010.01199.x

Caricato da

Sukoco HartonoDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Angiogranuloma Gingivaj.1834 7819.2010.01199.x

Caricato da

Sukoco HartonoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Australian Dental Journal 2010; 55:(1 Suppl): 5560

doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2010.01199.x

Gingival enlargements and localized gingival overgrowths

NW Savage,* CG Daly

*School of Dentistry, The University of Queensland and Maxillofacial Unit, The Royal Brisbane and Womens Hospital.

Discipline of Periodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, The University of Sydney.

ABSTRACT

Gingival enlargements are a common clinical nding and most represent a reactive hyperplasia as a direct result of plaque

related inammatory gingival disease. These generally respond to conservative tissue management and attention to plaque

control. However, a small group are distinct from these and whilst they also represent a reactive tissue response, this occurs

at the level of the supercial bres of the periodontal ligament. These epulides grow from under the free gingival margin and

not as a result of a primary inammatory gingival enlargement. This distinct aetiopathogenesis separates this group of

lesions both in terms of their specic clinical presentation and behaviour and their propensity for recurrence if managed

inadequately.

Keywords: Gingival enlargement, epulis.

Abbreviations and acronyms: AG = angiogranuloma; GCL = giant cell lesion; GVHD = graft-versus-host disease; PF = peripheral fibroma;

PGCG = peripheral giant cell granuloma.

INTRODUCTION

Gingival enlargement is a common nding in clinical

practice and the appropriate treatment depends on

correctly diagnosing the cause of the enlargement. The

most common form of enlargement is due to plaque-

induced inammation of the adjacent gingival tissues

(inammatory hyperplasia) and this tends to be asso-

ciated most commonly with the interdental papillae and

may be localized or generalized. Such gingival enlarge-

ment can be exaggerated by hormonal effects, as found

in puberty and pregnancy, and may also be complicated

by certain systemic medications.

1

Plaque-induced

inammatory hyperplasia should resolve with debride-

ment of plaque and calculus and improved oral hygiene,

especially when the gingival tissue is oedematous.

Where the gingival tissue is brotic, resolution of

enlargement may not occur, resulting in the persistence

of periodontal pocketing such that effective oral

hygiene is impeded. This scenario requires a more

detailed assessment and a longer term management

plan designed to map the level of gingival and possibly

periodontal involvement. Surgical management to

remove enlarged tissue and provide improved access

for the patients oral hygiene may be required.

In addition to plaque-induced gingival enlargement,

there are a number of other types ranging from the

bland gingival brous nodule

2

and retrocuspid papilla

3

to malignant disease. Historically, localized gingival

enlargements have been termed epulides,

4

a term

describing pedunculated or sessile swellings of the

gingiva. However, epulides is a topographic term which

gives no histologic description of a specic lesion and so

the term reactive lesion of the gingiva has often been

used instead.

5

This paper describes a subset of reactive lesions of the

gingiva

6

presenting as localized gingival enlargements.

For completeness, examples of localized and general-

ized gingival enlargements are detailed in Table 1.

Localized reactive gingival enlargements

5,6

constitute

a group of epulides with a number of distinguishing

features that clinically separate them from plaque-

induced inammatory enlargements. This distinction

allows a clinical diagnosis and denes a treatment

protocol designed to minimize recurrence.

7

The two dening features of this small cluster of

epulides are rstly, their derivation from the supra-

bony bres of the periodontal ligament and secondly,

their primary reactive and non-inammatory nature.

These allow a reasoned explanation for their clinical

appearance and behaviour. Specically, these epulides

do not originate from the gingival surface and so do

not simply represent an enlargement of the commonly

inamed interdental papilla. They can occur at any

2010 Australian Dental Association 55

Australian Dental Journal

The ofcial journal of the Australian Dental Association

site along the free gingival margin and characteristi-

cally grow out from the gingival sulcus with a cervical

displacement of the gingival margin. In many lesions,

the original free gingival margin can be seen running

across the lesion and this denes the site of origin, the

dominant direction of growth (supra or subgingival)

and the likely disruption to the attached gingiva and

mucogingival junction during any subsequent surgical

procedure (Fig 1). The dening features of this group

are shown in Table 2. The members of the group

identied for discussion are the brous epulis periph-

eral broma (PF), angiogranuloma pyogenic granu-

loma (AG) and the peripheral giant cell lesion gran-

uloma (PGCG). A number of large case studies

5,6

have

been published and these are consistent in the general

demographic features with PF being the most fre-

quently encountered, followed by AG, PF with calci-

cation and PGCG. There is some variation in

male female distribution but most favour a M:F ratio

ranging from 1:1.31 for PF to 1:1.99 for AG and 1:1.5

for PGCG.

6

The site and size also vary but with a

dominant presentation in the maxilla and size within

the 0.5 to 1.5 cm range.

Fibrous epulis peripheral broma

This lesion represents the archetype and most common

of the epulides with a female bias and predominantly

adult distribution. It is also the endpoint for some

epulides that may progressively mature and undergo

brosis, e.g., some angiogranulomas.

The PF is essentially a reactive brous hyperplasia.

The lesion typically presents in adults as a rm, pink

and uninamed mass growing from under the free

gingival margin or interdental papilla (Fig 2). The

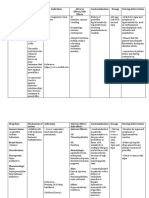

Table 1. Examples of localized and generalized gingi-

val enlargements

Developmental

Retrocuspid papilla

Fibrous nodule

Gingival cyst

Fibrous nodule

Reactive bromatosis gingivae

Focal mucinosis

Focal epithelial hyperplasia (viral)

Fibrous nodule

Hamartomatous

Gingival epithelial hamartoma

Cowdens syndrome

Idiopathic

Neoplastic

Benign malignant

Fig 1. Epulis growing from beneath the free gingival margin and

showing the derivation from the deeper tissues of the periodontium.

Table 2. Common features of epulides

Derivation from periodontal ligament

Develop from under free gingival margin

Reactive aetiology

Not primarily plaque related

High growth rate

High recurrence rate

Specic management requirements

Fig 2. Peripheral broma emanating from under the free gingival

margin and displacing this apically. There is a trauma related

inammation on the anterolateral aspect with central focal ulceration.

The lesion has extended into the previously existing diastema but has

not displaced the teeth.

Table 3. Differential diagnosis of angiogranuloma

Peripheral giant cell granuloma

Peripheral broma

Haemangioma

Pregnancy tumour

Periodontal granulation tissue

Kaposis sarcoma, bacillary angiomatosis

Non-Hodgkins lymphoma

Metastatic tumour

56 2010 Australian Dental Association

NW Savage and CG Daly

surface texture and presentation reects the previous

history of the lesion, e.g., hyperkeratosis or occasional

ulceration. The lesion is generally painless unless

traumatized during toothbrushing, ossing or eating.

There is no erosion of underlying bone and no

interdental spread unless there is a pre-existing dia-

stema or pre-existing interdental bone loss due to

chronic periodontitis. They may slowly increase in size

and some can reach impressive proportions and com-

promise the outcome of surgical removal, but this is an

uncommon nding.

The PF differs from a gingival hyperplasia in not

having dental plaque as a primary aetiological agent

and hence being non-inammatory unless secondarily

involved by plaque and calculus accumulation. Its

growth from under the gingival margin rather than

representing an inammatory enlargement of the sur-

face gingiva itself clearly distinguishes this lesion as a

separate entity.

The histological features of the PF readily separate

this lesion from gingival brous hyperplasia. The

lesion typically and diagnostically has a broblastic

reaction pattern although the peripheral sectors may

be mature and brocytic. The mass is discrete and

polypoid but non-encapsulated. The surrounding epi-

thelium is uninvolved and its histological appearance

reects the previous history of the surface with respect

to trauma and so varies from an atrophic, but

otherwise unremarkable epithelium, to areas of ulcer-

ation, although uncommon, and signicant hyperpla-

sia. This lesion frequently has a focus of calcication

which is variable and is seen as irregular dystrophic

calcication (peripheral broma with calcication) to

cementicles (PF with cementication) and trabeculae

of bone (PF with ossication). This latter feature is

responsible for the alternative term of calcifying

broblastic granuloma.

8

There is some evidence that

the calcication, generally regarded as dystrophic

calcication, may actually arise from pericyte differ-

entiation to osteogenic cells.

The treatment of the PF focuses specically on an

understanding of the derivation from the periodontal

tissues and so a supercial gingivectomy type proce-

dure will frequently result in recurrence. Mucoperio-

steal aps are best raised so that the lesion can be

excised entirely, suprabony connective tissue curetted

and the adjacent tooth and root surfaces debrided of

plaque and calculus or plaque-retaining factors in an

effort to minimize recurrence. The cosmetic result

will depend on the site of the lesion, the periodontal

bone support present and the amount of attached

gingiva (Figs 3a and 3b). Post-operative use of

antiseptic mouthrinses such as 0.2% chlorhexideine

gluconate should be utilized to assist healing

until mechanical oral hygiene procedures can be

restarted.

Angiogranuloma pyogenic granuloma

The angiogranuloma also presents mainly in adults and

although having some similarities to the PF, is clearly

distinguishable from it by recalling its very descriptive

title, angiogranuloma. The lesion is a smooth surfaced

mass, characteristically ulcerated (Fig 4), which grows

(a)

(b)

Fig 3. (a) A small peripheral broma on the labial aspect of 41 with

gingival margin displacement and showing the typical pink uninamed

appearance of this lesion. (b) The lesion has been removed with

attention to its deep attachment and a return of the gingival to its

premorbid status with no loss of contour or height.

Fig 4. Typically ulcerated angiogranuloma which is highly vascular

and has a characteristic red pink colour.

2010 Australian Dental Association 57

Gingival enlargements and overgrowths

from beneath the gingival margin and so displaces this

apically. Compared with the PF it is highly vascular,

variably compressible, typically bleeds readily and has a

characteristic red pink colour.

The angiogranuloma also shows the proliferative and

regenerative potential of the periodontium. This lesion

typically grows rapidly within the rst few weeks and

then slows to a gradual ongoing enlargement. Bone

erosion is uncommon but the mass can penetrate

interdentally and present as a bi-lobular mass con-

nected through the col area. Understandably, it has a

greater recurrence rate than the PF.

Histologically, the angiogranuloma accurately re-

ects its clinical presentation. It is an ulcerated and

inamed angiomatous lesion with numerous small

vascular channels and angioblastic foci consisting on

non-canalized clusters of endothelial cells. Many of

these brovascular lesions mature with the older basal

and lateral areas appearing brocytic and not dissimilar

to reactive gingival brous hyperplasias. Inammation

is inevitably present and its absence should raise the

possibility of a vascular malformation as opposed to an

angiogranuloma. The option of calling this lesion a

capillary haemangioma, granuloma type, has been

raised on a number of occasions but, given our current

understanding of the aetiopathogenesis of this lesion,

the term angiogranuloma seems most appropriate. A

current discussion on this issue has been presented by

Epivatianos et al.

9

Although micro-organisms may be

present on the surface, they are contaminants only and

the term pyogenic granuloma is a misnomer, but one

which persists even in the absence of any pyogenic

component.

The treatment is identical to the surgical excision of

the PF and recurrence, whilst signicant, seems depen-

dent on thorough surgical technique and primary

closure to minimize further proliferation of granulation

tissue.

9

The exception to this may be lesions that are

haemorrhagic and sclerotherapy

10

with injection of

sodium tetradecyl sulphate may be a consideration but

caution is required in consideration of the potential

toxicity and destructiveness of this agent. It has proven

useful in the authors practice in the treatment of lip

lesions as a preliminary procedure prior to denitive

surgical removal in a less hypervascular state. A recent

report also identies a possible role for corticosteroids

in treatment.

11

An interesting aspect of the angiogranuloma is its

appearance during pregnancy and hence the terms of

pregnancy epulis tumour and granuloma gravidarum

are used. The distinction between angiogranulo-

ma pyogenic granuloma and the pregnancy epulis is

clinical only, but the lesion is reported to occur in up to

5% or more of pregnancies.

12,13

These typically present

during the second trimester and, provided it does not

cause signicant functional restrictions or cosmetic

concerns, can be left until after delivery. Most preg-

nancy epulides will resolve fully approximately six

weeks post-partum or will reduce considerably in size

and be much less haemorrhagic, thus permitting easier

surgical excision. Failure to remove a residual mass

following pregnancy can lead to larger lesions at

subsequent pregnancies causing signicant functional

and cosmetic problems (Figs 5a and 5b).

The angiogranuloma can also occur in intraoral or

perioral sites unconnected with the gingiva, commonly

(a)

(b)

Fig 5. (a) Large multilobular angiogranuloma pregnancy epulis that

remained untreated following delivery with extensive involvement and

was removed after two years. (b) The excised lesion showing both

typical angiogranuloma and areas that have matured to a pink brous

tissue.

58 2010 Australian Dental Association

NW Savage and CG Daly

the lateral margin of the tongue and buccal mucosa

following trauma and the vermilion of the lip, partic-

ularly during pregnancy. In these sites management is

simple excision with a very low recurrence rate. There

have also been occasional associations with graft-vesus-

host disease (GVHD)

14

and following bone marrow

transplantation.

15

Peripheral giant cell granuloma

This lesion has also attracted a number of names, but

consideration of the histopathology and clinical behav-

iour

16

favours the above title. The peripheral giant cell

granuloma (PGCG) typically occurs in younger patients

and is common either as an isolated epulis in the

anterior mouth (Fig 6) or in the mixed dentition phase

in the posterior segments where teeth are erupting.

They are the most aggressive of the epulides and their

purplish-red almost cyanotic colour and propensity for

haemorrhage attests to a highly vascular lesion (Fig 7).

They will penetrate interdentally and bi-lobular lesions

are a common occurrence with associated erosion of the

adjacent cortical bone and separation of adjacent teeth

(Figs 8a and 8b) with their very signicant growth

potential.

17

The lesion is not restricted to periodontal

tissue and has been reported recently to occur with peri-

implant tissues.

18

A detailed analysis of their demo-

graphics and comparison with central giant cell lesions

has been reported by Motamedi et al.

19

The histology of this group is deceptively bland given

their clinical behaviour. The PGCG contains a single or

multi-nodular foci of mononuclear cells with proven

immunohistochemical derivation from the blood mono-

cyte lineage. They lie in a highly vascular brous stroma

interspersed with variable numbers of multi-nucleate

giant cells which are often closely related to the thin-

walled vascular channels. The lesion is not primarily

inamed although this is often a secondary focal

phenomenon due to local trauma or plaque related

inammation. The mass is partially surrounded by large

thin-walled vascular channels and this contributes to

the clinical cyanotic appearance and its haemorrhagic

tendency.

Fig 6. Typical highly vascular deeply coloured giant cell lesion with

lateral extension and displacement of the gingival margin.

Fig 7. Giant cell lesion with a multilobular contour and showing the

propensity for local extension often seen with this lesion.

(a)

(b)

Fig 8. (a) Giant cell lesion in a young patient with active displacement

of the coincident incisors and interdental spread. (b) Radiograph

showing interdental bone destruction caused by the PGCG.

2010 Australian Dental Association 59

Gingival enlargements and overgrowths

The histological appearance of the PGCG is impor-

tant as it explains the nature of this group of lesions and

their aggressive and often destructive clinical course.

They can be markedly haemorrhagic during surgery

and clinicians should be prepared to manage this,

particularly in the posterior areas of the mouth where

haemostasis can be difcult to obtain. The anterior

lesions are usually readily managed by a similar surgical

approach to the other epulides, but with the awareness

of likely bone erosion and requirement for very

thorough curettage of the supercial cortex and crestal

tissues. Suturing of a periodontal dressing material over

the excision site as a compression pack can assist with

haemostasis.

The PGCG is usually readily identied clinically due

to its colour and whilst it has the highest recurrence rate

of this group, it can generally be managed conserva-

tively. There are very occasional lesions that may recur

on multiple occasions and require extensive removal of

adjacent hard and soft tissues and, rarely, the involved

teeth. It is also worth noting that the peripheral PGCGis

unrelated to the central giant cell lesion (GCL) and they

should not be regarded as an extension of one other.

SUMMARY

Localized gingival enlargements represent a specic

group of lesions with a constant group of common

features but with distinctive clinical presentations and,

at least for the PGCG, an often aggressive clinical

course. They are reactive lesions emanating from the

supercial bres of the periodontal ligament and their

rapid growth is consistent with the high turnover rate of

the periodontal tissues. Removal must be thorough and

based on an understanding of the lesion type. Every

effort should be made to obtain primary closure of the

surgical site to facilitate healing and so discourage

proliferative granulation tissue formation which her-

alds early recurrence. Follow-up is required to ensure

that any recurrence is detected early and dealt with and

that the post-surgical gingival contour is maintained as

close as possible to its preoperative state.

REFERENCES

1. Seymour RA. Effects of medications on the periodontal tissues in

health and disease. Periodontol 2000 2006;40:120129.

2. Giunta JL. Gingival brous nodule. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral

Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1999;88:451454.

3. Brannon RB, Pousson RR. The retrocuspid papilla: a clinical

evaluation of fty-one cases. J Dent Hyg 2003;77:180184.

4. Cooke BED. The brous epulis and the bro-epithelial polyp:

their histogenesis and natural history. Brit Dent J 1952;93:305

309.

5. Kr Y, Buchner A, Hansen LS. Reactive lesions of the gingival. A

clinicopathological study of 741 cases. J Periodontol 1980;51:

655661.

6. Zhang W, Chen Y, An Z, Geng N, Bao D. Reactive gingival

lesions: a retrospective study of 2439 cases. Quintessence Int

2007;30:103110.

7. Bosco FB, Bonfante S, Luize DS, Bosco JMD, Garcia VG. Peri-

odontal plastic surgery associated with treatment for the removal

of gingival overgrowth. J Periodontol 2006;77:922928.

8. Dayoub S, Devlin H, Sloan P. Evidence for the formation of

metaplastic bone from pericytes in calcifying broblastic granu-

loma. J Oral Pathol Med 2003;32:232236.

9. Epivatianos A, Antoniades D, Zaraboukas T, et al. Pyogenic

granuloma of the oral cavity: comparative study of its clinico-

pathological and immunohistological features. Pathol Int

2005;55:391397.

10. Moon SE, Hwang EJ, Cho KH. Treatment of pyogenic granu-

loma by sodium tetradecyl sulphate sclerotherapy. Arch Dermatol

2005;141:644646.

11. Parisi E, Glick PH, Glick M. Recurrent intraoral pyogenic gran-

uloma with satellitosis treated with corticosteroids. Oral Dis

2006;12:7072.

12. Sills ES, Zegarelli DJ, Hoschander MM, Strider WE. Clinical

diagnosis and management of hormonally responsive oral preg-

nancy tumour (pyogenic granuloma). J Reprod Med 1996;41:

467470.

13. Saravana GHL. Oral pyogenic granuloma: a review of 137 cases.

Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009;47:318319.

14. Lee L, Miller PA, Maxymiw WG, Messner HA, Rotstein LE.

Intraoral pyogenic granuloma after allogeneic bone marrow

transplant. Report of three cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral

Pathol 1994;78:607610.

15. Kanda Y, Arai C, Chizuka A et al. Pyogenic granuloma of the

tongue early after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for

multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma 2000;37:445449.

16. Mighell AJ, Robinson PA, Hume WJ. Peripheral giant cell gran-

uloma: a clinical study of 77 cases from 62 patients, and literature

review. Oral Dis 1995;1:1219.

17. Bodner L, Peist M, Gatot A, Fliss DM. Growth potential of

peripheral giant cell granuloma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol

Oral Radiol Endod 1997;83:548551.

18. Hernandez G, Lopez-Pintor RM, Torres J, Vicente JC. Clinical

outcomes of peri-implant peripheral giant cell granuloma: a

report of three cases. J Periodontol 2009;80:11841191.

19. Motamedi MH, Eshghyar N, Jafari SM, et al. Peripheral and

central giant cell granulomas of the jaws: a demographic study.

Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007;

103:e39e43.

Address for correspondence:

Dr Neil W Savage

School of Dentistry

The University of Queensland

200 Turbot Street

Brisbane QLD 4000

Email: n.savage@uq.edu.au

60 2010 Australian Dental Association

NW Savage and CG Daly

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- dm2023 0146Documento12 paginedm2023 0146RvBombetaNessuna valutazione finora

- Oxford Handbook For Medical School 1st EditionDocumento1.153 pagineOxford Handbook For Medical School 1st EditionKossay Elabd100% (6)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- HemodynamicsDocumento40 pagineHemodynamicsBravo HeroNessuna valutazione finora

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- OET Speaking Criteria ChecklistDocumento4 pagineOET Speaking Criteria ChecklistNobomita GhoshNessuna valutazione finora

- Neuro SurgeryDocumento14 pagineNeuro Surgeryapi-3840195100% (4)

- P.E G-11 Physical Education and HealthDocumento16 pagineP.E G-11 Physical Education and HealthMikee MarceloNessuna valutazione finora

- Checklist & Algoritma ACLSDocumento16 pagineChecklist & Algoritma ACLSNadhif JovaldyNessuna valutazione finora

- Liver Transplantation and Hepatobiliary Surgery Interplay of Technical and Theoretical Aspects - 2020 PDFDocumento236 pagineLiver Transplantation and Hepatobiliary Surgery Interplay of Technical and Theoretical Aspects - 2020 PDFjimdio100% (3)

- Novo Nordisk Strategy Global Access Diabetes CareDocumento12 pagineNovo Nordisk Strategy Global Access Diabetes CareAmir IntizarNessuna valutazione finora

- A Colour Atlas of FundosDocumento132 pagineA Colour Atlas of FundosMohammed HosenNessuna valutazione finora

- Drug Study SARAHDocumento2 pagineDrug Study SARAHirene Joy DigaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Assignment in NCM 106 LectureDocumento6 pagineAssignment in NCM 106 LectureJeanessa Delantar QuilisadioNessuna valutazione finora

- General Abbreviations For Medical RecordsDocumento9 pagineGeneral Abbreviations For Medical Recordsjainy12Nessuna valutazione finora

- Brochure ICAS 2017Documento2 pagineBrochure ICAS 2017audslpkmc100% (1)

- Fever: Central Nervous System ConditionsDocumento14 pagineFever: Central Nervous System ConditionsthelordhaniNessuna valutazione finora

- The Developmental Epidemiology of Anxiety Disorders Phenomenology, Prevalence, and ComorbityDocumento18 pagineThe Developmental Epidemiology of Anxiety Disorders Phenomenology, Prevalence, and ComorbityShirleuy GonçalvesNessuna valutazione finora

- Acute Suppurative Otitis MediaDocumento41 pagineAcute Suppurative Otitis Mediarani suwadjiNessuna valutazione finora

- HDA 2018 Puerto Rico Mini Congress September 27-30 2018Documento2 pagineHDA 2018 Puerto Rico Mini Congress September 27-30 2018HispanicMarketAdvisorsNessuna valutazione finora

- Gordana Pavliša, Marina Labor, Hrvoje Puretić, Ana Hećimović, Marko Jakopović, Miroslav SamaržijaDocumento12 pagineGordana Pavliša, Marina Labor, Hrvoje Puretić, Ana Hećimović, Marko Jakopović, Miroslav SamaržijaAngelo GarinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Megan Marino ResumeDocumento2 pagineMegan Marino Resumeapi-474194492Nessuna valutazione finora

- Welcome AddressDocumento55 pagineWelcome AddressDiego RodriguesNessuna valutazione finora

- Cell Tissue Technology SDN BHDDocumento5 pagineCell Tissue Technology SDN BHDRaffandi RolandoNessuna valutazione finora

- Skripsi Jonathan Darell Widjaja 1206230025Documento41 pagineSkripsi Jonathan Darell Widjaja 1206230025Jonathan Darell WijayaNessuna valutazione finora

- Original PDF Medical Terminology Complete 4th Edition PDFDocumento41 pagineOriginal PDF Medical Terminology Complete 4th Edition PDFmegan.soffel782100% (35)

- Testosterone Therapy Fact SheetDocumento2 pagineTestosterone Therapy Fact SheetJonathan CastroNessuna valutazione finora

- Neonatal Seizures: Lamiaa Mohsen, M.D Cairo UniversityDocumento36 pagineNeonatal Seizures: Lamiaa Mohsen, M.D Cairo UniversityAdliah ZahiraNessuna valutazione finora

- Gram Negative Rods: Oxidase TestDocumento1 paginaGram Negative Rods: Oxidase Testnaura ghinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Guia Medica 2017Documento2 pagineGuia Medica 2017Anonymous FvWrRSyyfjNessuna valutazione finora

- Appendicitis NCPDocumento5 pagineAppendicitis NCPEarl Joseph DezaNessuna valutazione finora

- 10 - Dr. McDaniel - Sudden Onset Diplopia Should I Be AfraidDocumento6 pagine10 - Dr. McDaniel - Sudden Onset Diplopia Should I Be AfraidTamara AudreyNessuna valutazione finora