Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Icc's Nightmare The Prospect of Trying An Incumbent Head of State in A Foreign Country

Caricato da

opulitheTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Icc's Nightmare The Prospect of Trying An Incumbent Head of State in A Foreign Country

Caricato da

opulitheCopyright:

Formati disponibili

ICCS NIGHTMARE: THE PROSPECT OF TRYING AN INCUMBENT HEAD OF STATE IN A

FOREIGN COUNTRY

How Far Can The ICC Stretch Article 27 Of The Rome Statute?

By Boniface Njiru*

*LLB (University of Nairobi), LLM International and European Law (University of Amsterdam), Diploma in

International Criminal Law (European University Institute, Florence). The author is an Advocate of the High

Court of Kenya and a Lecturer at the Presbyterian University of East Africa. He is first Kenyan lawyer to be

placed on the List of Counsel of the International Criminal Court.

Contents

1. Introduction

2. The Immunity of Head of State and its exclusion for International Crimes.

3.0 Conclusion

4.0 Appendix

Abstract

Article 27 of the Rome Statute has turned out to be the most problematic provision for the ICC. This is

because the rule for exclusion of immunities for Heads of State and other high state officials as

originally formulated in the Nuremberg Charter and Tokyo Proclamation arose out of the horrifying

experiences during the First and Second World Wars situations. State officials who had subverted

instruments of government from their legitimate purpose and turned them into instruments of terror

and for committing heinous crimes were pursued across the country by victorious armies, captured

and then prosecuted in hastily contrived courts. The same may be said concerning the UN established

tribunals, the ICTY and ICTR. The rule however has taken a revolution under the Rome Statute and

heads of state and officials of otherwise stable states and legitimate governments may now be

summoned to The Hague to answer charges for committing ICC crimes. This seriously threatens State

sovereignty hitherto guaranteed under UN Charter. But is there a limit to the extent the ICC and other

international criminal tribunals can exclude the traditional immunities attaching to heads of states

and other high ranking officials, even for the most serious crimes?

1. INTRODUCTION

A crisis could be looming at the International Criminal Court concerning the Kenyan situation. In

the next few months Kenyans will go into a General Election where they will elect a new Head of

State[ii]. Among the contenders for the office of the President will be two ICC indictees, Uhuru

Muigai Kenyatta and William Samoei Ruto[iii]. The prospect of having a Head of State with an

appointment to keep with The Hague is no longer an idle thought, but is a serious possibility that is

already causing jitters around some circles. The ICC has so far studiously remained aloof from the

whole debate, refusing to interfere with Kenya's democratic process and leaving it all for Kenyans

to decide for themselves.[iv] But the matter is certainly disturbing given the number of high level

international visitors to Kenya who feel constrained to offer the Kenyan voter some unsolicited

advice on how to cast their vote.[v]

The focus of this article is on article 27 of the Rome Statute which excludes immunities and

privileges ordinarily enjoyed by heads of state and other government officials under international

law, if they are indicted before the ICC. The historical origin of the exclusion clauses contained in

article 27 is here examined and the question posed is whether the ICC can properly exercise

criminal jurisdiction over an incumbent Head of State democratically elected in a free and fair

election and then proceed to put him on trial in a foreign country over conducts that were not

committed while he was Head of State. Is there a limit to the jurisdiction that international courts

may exercise over incumbent Heads of States and other government officials or do they hold an

unlimited jurisdiction in this respect? Sovereign immunity is a fundamental principle of

international law and is an essential tool in international intercourse between states and for

maintenance of peace[vi]. It is suggested in this paper that by putting to trial a head of state of a

democratic state, the ICC would be exercising an exorbitant jurisdiction. In criminal law a court

exercises an exorbitant jurisdiction over an accused person when though valid rules are applied

according to the court's own procedure, the assertion of jurisdiction is nevertheless unreasonable,

unfair and excessive[vii]. It is a jurisdiction often exercised by courts of powerful states with a

political goal in mind. Such a jurisdiction would obviously be inappropriate for an international

criminal court. The ICC was created by states through a self-contained multilateral treaty of the

category known as law making or regime creating treaties which also settled the basis of the Court's

jurisdiction[viii]. Of course the ICC can simply stick to the black letter of the law and just assert its

jurisdiction, but by doing so it will have to ignore a number of important things, one being the

diplomatic embarrassment the trial of a sitting president is likely to cause the Governments of

Netherlands and Kenya. The state of Netherlands currently hosts the International Criminal Court

at The Hague. The ICC will also have to ignore the negative resulting impact the trial may occasion

on stifling the democratic aspirations of Kenyans. Kenya of today is by all standards not the same

that it was some five years back when the events under consideration by the ICC took place. Since

that time Kenyans have accomplished the great feat of adopting a new constitution through a

national referendum that was conducted in the year 2010, and have taken other impressive strides

towards giving Kenya a brand new face of a democratic State. New institutions of governance have

sprung up to enhance our democratic gains and there is a reinvigorated judiciary that is credibly

delivering quality judgements that meet international standards. Free expression has been spurred

up everywhere and public debate on important public issues is common; and then there are

impressive development projects that have given Kenya a facelift and are there for everyone to

witness.

In this comment we opine that the jurisdiction that the international courts exercise and one which

allows them to set aside sovereign immunities for heads of states and other state officials was not

created with the aim of upsetting the international rules that encourage states to intercourse, but

arose out of the horrifying experiences of the First and Second World Wars situations. State officials

in Hitler's government subverted legitimate instruments of government and turned them into

instruments for committing heinous crimes. State machinery and apparatus were so extensively

debased by the Nazi state officials that the entire government became one criminal enterprise

engineered towards committing unspeakable acts of cruelty. It was certainly incumbent on the

international community to take appropriate steps to confront this genre of evil through adoption

of freshly improvised criminal law tools. For state officials to use institutions of government for a

criminal purpose is totally unacceptable, but then for them to shield themselves from criminal

accountability by invoking the fiction of state sovereignty and official immunity from prosecution

for their despicable conducts, is simply outrageous. It is remarkable that the architects of so much

evil were never brought to justice to account for their abhorrent crimes. Hitler and Mussolini just

vanished in a cloud of rumours while Emperor Hirohito somehow escaped justice amidst

inexplicable excuses by the Allies. About 25 years previously Kaiser William of Germany another

war criminal of the First World War[ix] was allowed to escape justice in a similar fashion when

Netherlands refused to surrender him.

2. THE IMMUNITY OF HEAD OF STATE AND ITS EXCLUSION FOR INTERNATIONAL CRIMES.

a) Sovereign immunities of Heads of State

We cannot even start a serious discussion concerning international criminal justice without first

addressing the Head of State immunity and that of other high ranking officials. This is because

international criminal courts ordinarily fasten individual criminal responsibility on those said to be

most responsible for committing international crimes[x]. This class of people happens to coincide

also with those who are in control of state instruments and organization, and who enjoy trappings

of power and special constitutional privileges. Sovereign immunity attaching to the State must

however be distinguished from Head of State immunity though the latter derives from the former.

In the times when monarchical forms of government existed, it was considered that the King

enjoyed immunities similar to those conferred on the state because monarchs were identified with

the state itself. This has changed however in modern times with the democratization of government

and the diversification of the organs for governance, and the State now enjoys immunities that are

distinct from those of Head of State. This distinction has lately been emphasized by the

International Court of Justice in the case of Jurisdictional Immunities of the State- Germany and

Italy[xi] when it said,

"The Court concludes that, under customary international law as it presently stands, a State is not

deprived of immunity by reason of the fact that it is accused of serious violations of international

human rights law or the international law of armed conflict. In reaching that conclusion, the Court

must emphasize that it is addressing only the immunity of the State itself from the jurisdiction of the

courts of other States; the question of whether, and if so to what extent, immunity might apply in

criminal proceedings against an official of the State is not in issue in the present case."

Distinction must be made also between the most serious crimes of concern to the international

community as a whole, and other international crimes[xii]. The former involve commission of mass

criminality of a magnitude beyond what can possibly be committed without state involvement,

connivance and collusion. Their peculiar characteristic is that they are state based crimes driven by

responsible state officials standing in a position to pursue a violent agenda. International crimes on

the other hand such as torture, terrorism, human and drug trafficking, may be committed by private

actors although state officials may sometimes be involved in their commission. International

criminal law has zeroed on four core crimes said to be the most serious crimes of international

concern and these are crime of aggression, war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity upon

which no immunity can be invoked.

State officials enjoy two categories of immunities from prosecution, expressed in the Latin terms

Rationae Personae and Rationae materiae. These immunities are enjoyed both under national and

international law. Under domestic law, national constitutions determine the contents of immunities

and privileges that may be enjoyed by a whole range of state officials including members of

parliament, judges, state agencies etc. These include freedom from criminal and civil accountability

arising out their decisions or actions performed while in office. In international law however such

immunities arise from customary international law, which is the law recognised over a time in

settled state practice together with opinio juris sive necessitatis i.e. practice considered by states to

be of binding quality[xiii]. Much of the customary international law has now been codified into

international conventions or incorporated into domestic statutes. The 1648 Peace Treaty of

Westphalia that ended the European Wars is generally regarded as the beginning of the concept of

the modern state, principles of state sovereignty and territorial integrity. This form of government

is what is reflected under Article 2 of the UN Charter[xiv]. Therefore because all states are equal

and sovereign, the Head of State of one sovereign state cannot be subjected to the jurisdiction of the

courts of foreign states unless with his consent.

Rationae Personae immunities are personal immunities that attach to the person of the privileged

individual while still holding office and exempt him from being subjected to any form of legal

process whether criminal or civil including arrest, service of summonses or execution of a decree.

This is the highest form of immunity enjoyed by state officials and it is absolute in nature covering

all activities of the individual concerned whether for official or private acts, and whether arising

prior to his appointment to office or during incumbency. The only limitation to this form of

immunity is that it is exhausted once the person leaves office[xv]. The inviolability of the Head of

State from the indignity of having to answer to judicial process of the host state is therefore deemed

in international law to be crucially important, for without it intercourse between states may

become impossible. A recent case where rationae personae immunities were upheld in a judicial

proceeding was in the US case Tachiona v Mugabe.[xvi] A group of Zimbabweans sued President

Robert Mugabe, his Foreign Minister Stan Mudenge and the Zimbabwe ruling Party ZANU/PF for

torture and deprivation of property in Zimbabwe. Service of summons both for themselves and the

Party were served upon President Mugabe and Mr Mudenge while the two were attending a

conference in New York. The US Government filed a suggestion of immunity from legal process at

the District Court for Mugabe and Mudenge. The judge upheld the immunity of both Mugabe and

Mudenge since they were head of State and foreign minister respectively of a sovereign state and

struck out the suit against them. The District Court however maintained that it had jurisdiction over

ZANU/PF and proceeded to enter default judgement against the Party and to assess damages. The

US government appealed the decision. The Circuit Appeals Court affirmed the judgement of the

District Court striking out the suit on the basis of the immunity from legal process of Mugabe and

Mudenge, but went further to overturn the District Court's judgement against ZANU/PF that service

of summons on Mugabe and Mudenge as the representatives of the Party was proper service. The

absoluteness of the principle was explained by the Appeals Court as follows:

"As discussed above, see Part II (A), supra, section 11(g) of the U.N. Convention on Privileges and

Immunities extends to Mugabe and Mudenge the immunities that diplomats enjoy under the Vienna

Convention. These include not only the immunity from legal process set forth in Article 31, but also

the "inviolability" of the person: [emphasis mine].

"The person of a diplomatic agent shall be inviolable. He shall not be liable to any form of arrest or

detention. The receiving State shall treat him with due respect and shall take all appropriate steps to

prevent any attack on his person, freedom or dignity".

The Government argues that the district court erred in holding that Article 29 of the Vienna

Convention did not protect Mugabe and Mudenge from service of process as agents for ZANU-PF. We

agree. Although the term "inviolable" is not defined in the Vienna Convention, we have described it as

"advisedly categorical" and "strong." 767 Third Ave. Assocs. v. Permanent Mission of Zaire, 988 F.2d

295, 298 (2d Cir.1993) (discussing inviolability of mission premises under Article 22 of the Vienna

Convention). The text of Article 29 makes plain that a person entitled to diplomatic immunity may not

be arrested or detained. The scope of inviolability, however, extends further; Article 29 also protects

against "attack[s]" on the "person, freedom or dignity" of the diplomatic envoy. For example, courts

have held that the inviolability principle precludes service of process on a diplomat as agent of a

foreign government, see Hellenic Lines, Ltd. v. Moore, 345 F.2d 978, 979-81 (D.C.Cir.1965), and, as

applied to missions, prevents a landlord from seeking to evict a diplomatic mission from its premises

for non-payment".

Rationae Materiae immunities or functional immunities on the other hand are more difficult to

establish because they attach to what are called official acts' of the privileged individual. They do

not come to an end even after the state official has ceased holding office. A whole range of officials

enjoy functional immunities including minor officials so long as they were acting on behalf of the

state and are thus exempted from criminal and civil actions. In this respect the acts of the official

concerned are deemed to have been performed on behalf of the State and therefore are attributed

to the state itself. The Appeals Chamber of ICTY in the Blaskic Judgement (Prosecutor v Thomir

Blaskic) observed that state officials acting in their official capacity "are mere instruments of a State

and their official action can only be attributed to the State. They cannot be the subject of sanctions or

penalties for conduct that is not private but undertaken on behalf of a State. In other words, State

officials cannot suffer the consequences of wrongful acts which are not attributable to them personally

but to the State on whose behalf they act: they enjoy so-called "functional immunity". This is a well-

established rule of customary international law going back to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

, restated many times since".[xvii]

What then are the official acts for which an official can claim immunity as opposed to private acts

for which he may be held accountable? Can a state authorize the commission of crimes, or more

particularly international crimes? The answer to the question was given in the affirmative in the

Pinochet (3) Case[xviii].Lord Goff of Chieverley expressed the principle as follows: "In my opinion,

the principle which I have described cannot be circumvented in this way. I observe first that the

meaning of the word 'functions' as used in this context is well established. The functions of, for

example, a head of state are governmental functions as opposed to private acts; and the fact that a

head of state does an act other than a private act, which is criminal does not deprive it of its

governmental character. This is as true of a serious crime such as murder or torture as it is of a lesser

crime".

Lord Goff then proceeded to quote Lord Bingham of Cornhill C.J. who said as follows:

"a former head of state is clearly entitled to immunity in relation to criminal acts performed in the

course of exercising public functions. One cannot therefore hold that any deviation from good

democratic practice is outside the pale of immunity. If the former sovereign is immune from process in

respect of some crimes where one does draw the line?"

As noted, opinion is divided as to whether a head of state also enjoys immunity from prosecution

for international crimes. Surprisingly in The Case Concerning the Arrest Warrant of 11 April 2000

Democratic Republic of Congo v Belgium [xix] the International Court of Justice, which is the judicial

organ of the United Nations, in a very guarded language held that as between states, heads of states

could enjoy immunity from prosecution even for the most serious crimes. In that case a Belgian

investigating magistrate issued an international warrant of arrest against the Foreign Minister of

Congo Mr Yerondia Ndombasi for war crimes and for committing crimes against humanity. Congo

filed an application at the ICJ complaining a violation of its sovereignty by Belgium. The Court

upheld Congo's application and in the course of its judgement made some important observations.

It said,

"The Court has carefully examined State practice, including national legislation and those few

decisions of national higher courts, such as the House of Lords or the French Court of Cassation. It has

been unable to deduce from this practice that there exists under customary international law any form

of exception to the rule according immunity from criminal jurisdiction and inviolability to incumbent

Ministers for Foreign Affairs, where they are suspected of having committed war crimes or crimes

against humanity. The Court has also examined the rules concerning the immunity or Criminal

responsibility of persons having an officia1 capacity contained in the legal instruments creating

international criminal tribunals, and which are specifically applicable to the latter. It finds that these

rules likewise do not enable it to conclude that any such an exception exists in customary international

law in regard to national courts".

b. The Advent of crimes against international law

The manner in which international criminal law has treated Heads of States immunities may be

examined in three phases (1) The Nuremberg phase i.e. the Second World War cases, (2) the Post

Nuremberg Phase and (3) the current phase expressed in the Rome Statute.

(i) The Nuremberg Phase

In the judgement of October 1946 the Nuremberg Tribunal made a statement that has come to be

regarded as the classic catch- phrase of international criminal law that, "Crimes against

International Law are committed by men, not by abstract entities, and only by punishing individuals

who commit such crimes can the provisions of International Law be enforced."[xx] While this

statement is no doubt important, international criminal law has also not been able to create a clear

distinction between the criminal responsibility of the men' who commit international crimes, and

responsibility of states for committing international crimes. When a government adopts a criminal

policy of terrorizing and exterminating sections of the population, criminal responsibility of the

individual and that of the State becomes blurred and inextricably intertwined. The very horror of

international crimes and the only justification there is for excluding international law immunities

and special privileges from Heads of States and states officials is that the perpetrator perverted

legitimate instruments of state from their purpose of maintaining law and order and turned them

into instruments of creating terror and committing mass crimes. These individuals used state

machinery to accomplish heinous criminal purposes and yet want to invoke their official position to

escape the consequences of their wicked deeds. Unfortunately this is the history of international

criminal law as we will discover in this comment. The Nuremberg Tribunal American Chief

Prosecutor Justice Robert Jackson[xxi] aptly summarised the legal reasoning behind the exclusion

provisions in the Nuremberg Charter when he said,

"The Charter recognizes that one who has committed criminal acts may not take refuge in superior

orders nor in the doctrine that his crimes were acts of states. These twin principles working together

have heretofore resulted in immunity for practically everyone concerned in the really great crimes

against peace and mankind. Those in lower ranks were protected against liability by the orders of

their superiors. The superiors were protected because their orders were called acts of state. Under the

Charter, no defence based on either of these doctrines can be entertained".

The tribunal agreed. "The authors of these acts" the tribunal said "cannot shelter themselves behind

their official position in order to be freed from punishment in appropriate proceedings".

Adolf Hitler and the Reich government committed apocalyptic crimes that were so evil in form and

so shocking, that the whole world was shaken into a realization that a new genre of evil had

attacked the human race even threatening it with extinction. He was able to commit such

monumental crimes by seizing the Germany Government which he then perverted into an

instrument for commission of unspeakable crimes. It is beyond belief that one human being could

be so evil as to ascribe to himself the authority that Hitler did, even to the extent of denying his

fellow human beings the bare right to exist. Hitler and the Nazi government created the Holocaust

that decimated some 6 million Jews, set up concentration and labour camps where opponents were

starved to death and the gas chambers where women, children and the weak members of the

society were suffocated before being incinerated. A Prosecutor in Nuremberg Trials Benjamin

Ferencz[xxii] described the horrifying Nazi operation as follows:-

"Hitler began the German march of conquest over Europe. Behind the Blitzkrieg of the German tanks

came the Einsatzgruppen to murder without pity or remorse every Jewish man, woman or child, every

gypsy or perceived adversary they could catch. Prisoners of war were executed or starved to death,

millions of civilians were forced into slave labour, while those unable to work were simply annihilated

in gas chambers and concentration camps. Japanese troops committed similar crimes in areas they

occupied. Repeated Allied warnings that those responsible for atrocities would be held to account went

unheeded. The British proposed that, when the war was won, prominent Nazis be taken out and simply

executed. It could have come as a relief but not as a surprise when defeated German and Japanese

leaders found themselves in the dock to answer for their deeds in a court of law".

The 1945 Charter of the International Military Tribunal for the Prosecution and Punishment of

Major War Criminals was really the first international legislative instrument that addressed

immunities from prosecution for heads of States in respect of the conducts enumerated in the

Charter. Article 7 of the Charter provided that

the official position of defendants, whether as Heads of State or responsible officials in Government

Departments, shall not be considered as freeing them from responsibility or mitigating

punishment'.

The same provision was repeated unchanged as Article 2(4) (b) of the Control Council no 10 for the

Punishment of Persons Guilty of War Crimes, Crimes against Peace and Against Humanity and

adopted with some modifications as Article 6 of The Tokyo Charter of the International Military

Tribunal. It was clear that what occupied the minds of the prosecutors during the Nuremberg years

was the extreme criminalization of the entire machinery of Government by the Nazis and their

allies. The Prosecutors indicted Nazi government organs for being criminal organizations and

produced indictments criminalizing the entire Hitler's Cabinet, the secret Police, the Army

command and several other government departments that were used to pursue Hitler's criminal

policy. Though the Nuremberg tribunal judges refused to criminalize the Hitler Cabinet, the

dissenting judgement of the Soviet Union Judge harshly chided his colleagues for refusing to declare

the Hitler government a criminal organization. The dissenting judgement captures the thinking of

this period in the following words:

"The Tribunal considers it proven that the Hitlerites have committed innumerable and monstrous

crimes. The Tribunal also considers it proven that these crimes were as a rule committed intentionally

and on an organized scale, according to previously prepared plans and directives ("Plan Barbarossa",

"Night and Fog", "Bullet", etc.).The Tribunal has declared criminal several of the Nazi mass

organizations founded for the realization and putting into practice the plans of the Hitler Government.

In view of this it appears particularly untenable and rationally incorrect to refuse to declare the Reich

Cabinet the directing organ of the State with a direct and active role in the working out of the criminal

enterprises, a criminal organization. The members of this directing staff had great power, each headed

an appropriate Government agency, each participated in preparing and realizing the Nazi

Programme".

The Nuremberg phase however suffers one serious setback expressed by Professor Kelsen as

victor's justice'[xxiii]. The tribunals were set up by the victorious allied powers who after

occupying Germany and Japan decided on the law to be applied with the single aim of punishing

their vanquished foes and appointed judges and prosecutors to apply the system they had created.

(ii) The Post Nuremberg Phase

The Post Nuremberg phase has been marked by the UN Security Council directly, though

controversially, establishing or assisting the establishment of a series of international criminal

tribunals along the very lines of the post-World War 11 courts. After the Nuremberg Trials the UN

General Assembly directed the International Law Commission to formulate principles of

international law distilled from the Nuremberg Charter and the IMT judgement and also draw a

Draft Code of offences[xxiv] to be used in creating an international criminal court of the future. The

international criminal court was not created immediately as expected due to the Cold War events

but for our purpose Principle III of the Nuremberg Principles provided as follows;

"The fact that a person who committed an act which constitutes a crime under international law acted

as Head of State or responsible Government official does not relieve him from responsibility under

international law"[xxv]

Article 3 of the 1954 ILC Draft Code of Offences against the Peace and Security of Mankind

contained a similar provision.[xxvi] The same provisions with the same standard wording were

reproduced as Article 7(2) of the 1993 Statute of the International Tribunal of the Former

Yugoslavia[xxvii], as Article 6(2) of the 1994 Statute of the International Tribunal for

Rwanda[xxviii] and as Article 6(2) of the 2002 Statute of the Special Court for Sierra Leone[xxix].

There is a paucity of judicial opinions, less than one would in fact expect, arising from the Ad Hoc

International Criminal Tribunals concerning the Head of State immunity. In the first Tribunal case

relating to a former Head of State, Prosecutor v Jean Kambanda[xxx] the ICTR did not even mention

the head of state immunity in relation to the accused, but In the Milosevic case the ICTY dealt

superficially with the issue when the Tribunal's competence over a former head of state was

challenged by the Amici curiae[xxxi]. The tribunals' decisions have however one common

characteristic: that is their insistence that they enjoyed a special relationship with the UN Security

Council, raising the question then whether the ad hoc tribunal's power arose from customary

international law or from the special enforcement power of the UN Security Council. In the Blaskic

Decision the Appeals Chamber did point out that the ICTY as a UN subsidiary body created under

Chapter VII of the UN Charter stood in a vertical relationship vis--vis states and could issue orders

binding on states. The Appeals Chamber however rejected the notion that international courts in

this respect enjoyed unlimited power over State Officials and declined to issue orders citing general

principles of international law that affords protection to State Sovereignty. All the same the

Tribunal observed that there was an exception in this respect when it comes to serious crimes of

concern to the international community as a whole. The Chamber observed

"The few exceptions relate to one particular consequence of the rule. These exceptions arise from the

norms of international criminal law prohibiting war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide.

Under these norms, those responsible for such crimes cannot invoke immunity from national or

international jurisdiction even if they perpetrated such crimes while acting in their official capacity".

[xxxii]

In the Krstic Decision the ICTY unconvincingly sought to depart from the Blaskic decision despite a

strong dissenting opinion from Judge Shahabuddeen[xxxiii]. As we have noted already the ICJ in the

Arrest Warrant Case did not entirely agree that state officials cannot invoke immunity before

national jurisdictions in respect of the most serious international crimes. The ICJ noted obiter

dictum that an incumbent or former minister of Foreign Affairs enjoys procedural immunities

before national courts but "may be subject to criminal proceedings before certain international

criminal courts, where they have jurisdiction."[xxxiv] So the question will arise when they have

that jurisdiction and when they do not possess it. An important decision on Head of State immunity

before international courts was delivered by the Special Court of Sierra Leone in the Charles Taylor

Case[xxxv]. It is important however to remember that Taylor had already lost the status of Head of

State when the decision was being delivered. The Special Court in its decision had to contend with

the defence assertion that it was a mere domestic court of Sierra Leone and so the Court's mind was

heavily pre-occupied with having to defend its status of being an international criminal Court

established by the UN Security Council.

(iii) Article 27 of the Rome Statute

The current position concerning head of state immunities is expressed in the Rome Statute

establishing the International Criminal Court. Article 27 of the Statute has turned to be the most

problematic provision relating to the Court's jurisdiction and one that is about to bring the

institution down to its knees. The Article is more elaborately structured than similar provisions

contained under the IMT Charter, the Nuremberg Principles or the Statutes of the Ad Hoc Tribunals.

It is framed in two paragraphs, the first paragraph dealing with official capacities of Heads of States,

or Government, members of government or Parliament, elected representatives or government.

The structure of the paragraph leaves no doubt that it is the Rationae Materiae immunities of state

officials that are being excluded by this part. Paragraph 27(2) is more difficult because it deals with

jurisdictional immunities Rationae Personae. This paragraph stipulates that personal immunities

cannot bar the ICC from exercising jurisdiction. As the ICC seeks to assert its authority as a

supranational Court it is faced with insurmountable hurdles arising from its application of Article

27 provisions. Here we make the following observations:

1. There is an innate weakness in the ICC structure because of its being delinked from the

United Nations system. The ICC cannot therefore move with the same confidence and

assertiveness over states and governments as the ad hoc Tribunals which could always fall

back to Chapter VII of the UN Charter as a subsidiary organ of the Security Council

bestowed with the special function for maintenance of peace and security. The Appeals

Chamber of the ICTY in the Decision on the Defence Motion on Interlocutory Appeal

Jurisdiction[xxxvi] emphasized the basis for the establishment of the Tribunal as follows,

"The Security Council has resorted to the establishment of a judicial organ in the form of an

international criminal tribunal as an instrument for the exercise of its own principal function of

maintenance of peace and security, i.e., as a measure contributing to the restoration and maintenance

of peace in the former Yugoslavia".

As a treaty based Court the ICC is disadvantaged in this respect and cannot resort to the authority of

UN Charter except where a referral has been made by Security Council under Article 13(b) of the

Rome Statute as in the case of Darfur[xxxvii].

1. The ICC suffers an image problem because its claim to universality is seriously dented by

the absence of the major world powers such as USA, China, Russia, India and Pakistan from

the slate of state parties. That means that the ICC has to tread wearily because over half of

the world population that reside in these states are not subject to the Court's

jurisdiction.[xxxviii] The ad hoc Tribunals could always surmount this hurdle by arguing

that as a creation of the UN Security Council it had the support of the entire membership the

UN. In its decision of 12th December 2011 Prosecutor vs. Omar Hassan Ahmad al

Bashir[xxxix] the Pre-trial Chamber 1 alluded to the fact that because 120 states had ratified

the Statute and that even non states parties had twice approved prosecution of other

countries Heads of States therefore it could deduce a general practice having emerged of

prosecuting Heads of States before international courts. What the Pre-Trial Chamber failed

to observe was that these non-states parties are actually the major powers that dominate

world politics militarily and economically and as such are driven by self-interest[xl].

Nowhere else has the application of naked power over international law been so openly

displayed as in the attitude adopted by major powers towards the ICC. The US for instance

not only withdrew its signature from the Rome Statute, but even publicly campaigned

against the Court by preparing Article 98(2) agreements and passing laws threatening weak

states with sanctions if they did not sign them. Despite its long time disagreement with the

ICC, the United States determinedly attends all meetings of the Assembly of States Parties

ostensibly to offer support for the ICC but in reality to make sure that no decisions are

passed that have an adverse effect on US interests[xli].It is astounding that the Pre-Trial

Chamber could draw a favourable inference from such lukewarm support. Major Powers

may render support to the ICC when the Court is targeting weak states and when their own

leaders are not the focus of investigations, but will react quite violently if their heads of

states are threatened with prosecution.

3. Article 27 and article 98 are directly controversial and contradictory. It is evident that Article 98

is critical to curbing and limiting the ICC's interference over states sovereign rights, immunities of

state officials and from upsetting international order. The ICC admitted in the Al Bashir case( just

quoted) that there exists a tension between these two articles of the Rome Statute and yet

proceeded to cite Article 119(1) as the basis for decision given by the Pre-trial Chamber to define

its own judicial functions. The reliance placed on Article 119(1) itself is controversial and one

would have expected the Court to identify the nature of the dispute as one concerning the

obligations of states towards each other and as such Article 119(2) would be more appropriate in

addressing the issue at hand by seeking a determination to be made either by the Assembly of

States Parties or the International Court of Justice. Article 98 may be contrasted with Article 27.

Whereas Article 98 appears at the co-operation structure of the Statute under the heading "Co-

operation With Respect To Waiver Of Immunity And Consent To Surrender"[xlii] Article 27 is

placed in Part 3 under the heading GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF CRIMINAL LAW. General principles

have a historical significance in that they are designed to safeguard the fair trial rights of an accused

person. Professor Otto Trifterer,[xliii] a foremost authority in international criminal law, observes,

"Article 98 seems at first sight as contradictory and inconsistent with article 27. But article 98 does

not limit the criminal responsibility under substantive law. It deals with the situations where the

exercise of the Court's jurisdiction may be blocked as it is in other cases where the suspect is not

available before the Court. The ratio behind Article 98 is that states should not be obliged to break

their international obligations by surrendering suspects to the Court, even if this leads to impunity"

Professor Triffterer also observes also that Article 25(4) excludes questions of state responsibility

from the ICC jurisdiction[xliv]. He noted that

"The Rome Statute does not deal with any form of state responsibility for commission of crimes. But it

clearly expresses that the individual criminal responsibility established by the Statute shall not affect

the responsibility of states under international law. Since there is no state responsibility under the

Statute it can only mean responsibility of states outside the Statute"

Any State that is faced with the prospect of arresting a Head of State or any other official will have

to first determine whether by doing so that state would be in breach of international law relating to

immunities which is what the Republic of Malawi tried to tell the Court. The immensity of the

problem is well illustrated by the standoff between the AU and the ICC over President Al Bashir of

Sudan and the international discussion over the subject[xlv] .The AU's interpretation of Article 98

seems to be similar to that of Professor Triffterer, and the AU accuses the ICC of changing

customary international law. An excerpt of the AU Commission statement is worth reproducing

here as it summarises the dilemma posed by the two articles follows,

"The AU Commission wishes to point out that Article 27(2) of the Statute provides that "Immunities or

special procedural rules which may attach to the official capacity of a person, whether under national

or international law, shall not bar the Court from exercising its jurisdiction over such a person".

However, this Article 27 appears under the part of the Statute setting out general principles of

criminal law' and applies only in the relationship between the Court and the suspect. In the

relationship between the Court and states, article 98(1) applies. This Article provides: "The Court may

not proceed with a request for surrender or assistance which would require the requested State to act

inconsistently with its obligations under international law with respect to the State or diplomatic

immunity of a person or property of a third State, unless the Court can first obtain the cooperation of

that third State for the waiver of the immunity". As a general matter, the immunities provided for by

international law apply not only to proceedings in foreign domestic courts but also to international

tribunals: states cannot contract out of their international legal obligations vis--vis third states by

establishing an international tribunal. Indeed, contrary to the assertion of the ICC Pre-Trial Chamber I,

article 98(1) was included in the Rome Statute establishing the ICC out of recognition that the Statute

is not capable of removing an immunity which international law grants to the officials of States that

are not parties to the Rome Statute. This is because immunities of State officials are rights of the State

concerned and a treaty only binds parties to the treaty. A treaty may not deprive non-party States of

rights which they ordinarily possess. In this regard, it is to be recalled that the immunity accorded to

senior serving officials rationae personae, from foreign domestic criminal jurisdiction (and from

arrest) is absolute and applies even when the official is accused of committing an international crime".

A disagreement of this magnitude between the ICC and states parties cannot be healthy for the

Court's functioning. Professor Jan Klabbers has pointed that the legal relationship between

international organizations and its member states can be complicated and may lead to uncertainty

in the law relating to international organizations[xlvi]. The African Heads of States have requested

its Commission to seek an advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice which should be

sorted out with utmost urgency[xlvii].

3. CONCLUSION

If the Kenyan electorate defies international pressure and elect a Head of State with an ICC

indictment on him, the scene at the ICC will be quite novel in the history of international criminal

justice. It will be the first time ever that a head of state of a democratic and stable state who has

assumed office through a democratic process will be subjected to a trial before an international

criminal court for conducts that did not occur while he was head of state. Hitherto heads of state

who have sat at the dock of international tribunals to answer criminal charges were fallen bloody

dictators who having been pursued across war ravaged fields by victorious armies, were captured

and brought to quick justice. Such were the Rwandese Prime Minister Jean Paul Kambanda , Serbian

President Slobodan Milosevic, Iraq President Saddam Hussein and others. Article 27 of the Rome

Statute was not conceived for this type of situation. In the opinion of this author a trial of a sitting

head of state of a democratic state by the ICC constitutes not only an exorbitant exercise of

jurisdiction but an overstretching and overloading of its jurisdiction which has caused the Court to

be drawn into incessant controversies with member states. The future International Criminal Court

with unlimited power to set aside the traditional immunities attached to heads of states and

responsible state officials of democratic states and send them off to stand trial in a foreign state is a

frightening behemoth. Not only is the sovereign equality of states enshrined in article 2 of the UN

Charter threatened but it is a diminution of the principle of complementarity. We conclude this

article with this quote attributed to Mary Shelley by Professor Jan Klabbers "You are my creator but

I am your master; obey!"[xlviii]

Appendix

[i] Article 27 of the Rome Statute provides as follows:

"1. This Statute shall apply equally to all persons without any distinction based on official capacity. In

particular, official capacity as a Head of State or Government, a member of a Government or

parliament, an elected representative or a government official shall in no case exempt a person from

criminal responsibility under this Statute, nor shall it, in and of itself, constitute a ground for reduction

of sentence.

2. Immunities or special procedural rules which may attach to the official capacity of a person,

whether under national or international law, shall not bar the Court from exercising its jurisdiction

over such a person".

[ii] The Court of Appeal in Civil Appeal no 74&82 of 212 (2012 eklr) determined the date of the

General Election to be 4th March 2013

[iii] Hon Uhuru Muigai Kenyatta, Kenya's Deputy Prime Minister heads the TNA Party while Hon

William Ruto heads the Republican Party of Kenya. The two parties have now joined up in a

coalition.

[iv] See statements by ICC Prosecutor Moreno Ocampo of 24th January 2012 and Prosecutor

Bensouda of 22nd October 2012 www.icc-cpi.int

[v] High level visitors such as US Secretary Hillary Clinton and Mediator Koffi Annan have

expressed concern about the possibility of electing an ICC indictee.

[vi] See "Immunities of State Officials, International Crimes and Foreign domestic Courts" by Depo

Akande and Sangeeta Shah, European Journal of International Law page 818

[vii] See "United States Jurisdiction over Extraterritorial; Crime" by Christopher L Blakesley, Journal

of Criminal Law and Criminology. See also Madeleine Morris High Crimes and Misconceptions: The

ICC and Non Party States' .Law and Contemporary Problems Vol 64:no 1 page 13.The article can be

accessed at www.law.duke.edu/journals/64LCP Morris

[viii] For a discussion on Law Making Treaties see Catherine Brolmann Law-Making Treaties: Form

and Function in International Law' 2005 Nordic Journal of International Law 74:383-404

[ix] Article 227 of the 1919 Versailles Peace Treaty provided for the indictment of the Kaiser of the

supreme Offence against international morality and the sanctity of treaties. He was never tried

[x]The Office of the Prosecutor in the 2003 Policy Paper stated that policy as follows,

"The Court is an institution with limited resources. The Office will function with a two-tiered approach

to combat impunity. On the one hand it will initiate prosecutions of the leaders who bear most

responsibility for the crimes. On the other hand it will encourage national prosecutions, where

possible, for the lower-ranking perpetrators, or work with the international community to ensure that

the offenders are brought to justice by some other means. The strategy of focusing on those who bear

the greatest responsibility for the crimes may leave an "impunity gap" unless national authorities, the

international community and the Court work together to ensure that all appropriate means for

bringing other perpetrators to justice are used. In some cases the focus of an investigation by the Office

of the Prosecutor may go wider than high-ranking officers if, for example, investigation of certain

types of crimes or those officers lower down the chain of command is necessary for the whole case. For

other offenders, alternative means for resolving the situation may be necessary, whether by

international assistance in strengthening or rebuilding the national justice systems concerned, or by

some other means. Urgent and high-level discussion is needed on methods to deal with the problem

generally".

[xi] ICJ Judgement of 3rd February 2012.

[xii] Under Article 5 of the Rome Statute the jurisdiction of the ICC is limited to the most serious

crimes of concern to the international community as a whole.

[xiii] See ICJ Decision in North Sea Continental Shelf Cases ICJ Report 1969 paragraph 77

[xiv] Article 2(1) of the Charter provides "The Organization is based on the principle of the sovereign

equality of all its Members".

[xv] See Articles 29 and 31 of the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations, 500 UNTS 95

entered n force on 24th April 1964.

[xvi] 386 F.3d 205.This case began from the Southern District Court of New York

[xvii] Judgement of 29th October 1997 paragraph 38

[xviii] Reg v. Bow Street Magistrate ex parte Pinochet (3) [1999 WLR 827. Lord Goff of Chieverley's

opinion is at page 848

[xix] ICJ Reports 2002 page 3 Judgement of 14th February 2002

[xx] Read the Nuremberg Judgement at the website of the Nizkor Project www.nizkor.org (Law of

the Charter Part 2)

[xxi] Opening speech of Robert Jackson www.nizkor.org (Part 8 Second day Wednesday 21st

November 1945)

[xxii]From Nuremberg to Rome: A Personal Account' by Benjamin Ferencz. www.benferencz.org

[xxiii] See Article by Andrea Gattini Kelsen's Contribution to International Criminal Law' September

2004 Journal of International Criminal Justice Volume2 no 3 page 795

[xxiv] The General Assembly resolution read as follows:

Formulation of the principles recognized in the Charter of the Nilrnberg Tribunal and in the judgment

of the Tribunal

The General Assembly

Decides to entrust the formulation of the. principles of international law recognized in the Charter of

the Niirnberg Tribunal and in the judgment of the Tribunal to the International Law Commission, the

members of which will, in accordance with resolution 174 (Il), be elected at the next session of the

General Assembly, and

Directs the Commission to

(a) Formulate the principles of international law recognized in the Charter of the Niirnberg Tribunal

:md in the judgment of the Tribunal, and

(b) Prepare a draft code of offences against the peace and security of mankind, indicating clearly the

place to be accorded to the principles mentioned in sub-paragraph (a) above.

[xxv] http//untreaty.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/draftarticles/7_1... PDF file

[xxvi] http://untreaty.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/draftarticles/7_3_1954.pdf

[xxvii] Established by UN Security Council Resolution 827(1993), Article 7(2) ICTY Statute provides

"The official position of any accused person, whether as Head of State or Government or as a

responsible Government official, shall not relieve such person of criminal responsibility nor

mitigate punishment."

[xxviii] Established by UN Resolution 955(1994)

[xxix]Established by an Agreement between the United Nations and the Government of Sierra

Leone dated 16th January 2002.

[xxx] ICTR-97-23-S Judgement and Sentence of 4th September 1998

[xxxi] Decision on Preliminary Motions -8th November 2001

[xxxii] Ibid note 14

[xxxiii] Decision on application for Subpoenas Prosecutor v Radislav Krstic of 1st July 2003

[xxxiv] Ibid note 16.

[xxxv] Decision on Immunity from Jurisdiction Prosecutor v Charles Ghankay Taylor 31st May 2004

[xxxvi] Decision of 2nd October 1995 Prosecutor vs.Dusco Tadic a/k/a Dule

[xxxvii] Security Council Resolution no 1593(2005)

[xxxviii] See Report by David Hoile Is the ICC Fit for Purpose?' New African Magazine of March 2012

[xxxix] ICC -02/05-01/09 Situation in Darfur, Sudan

[xl] The Pre-Trial Chamber actually said, "Even some States which have not joined the Court have

twice allowed for situations to be referred to the Court by United Nations Security Council Resolutions,

undoubtedly in the knowledge that these referrals might involve prosecution of Heads of State who

might ordinarily have immunity from domestic prosecution".

[xli] At the Kampala Review Conference the USA ensured that no resolution concerning the crime of

aggression would affect non-state parties.

[xlii] Article 98 reads as follows, "1. The Court may not proceed with a request for surrender or

assistance which would require the requested State to act inconsistently with its obligations under

international law with respect to theState or diplomatic immunity of a person or property of a third

State, unless the Court can first obtain the cooperation of that third State for the waiver of the

immunity. (2). The Court may not proceed with a request for surrender which would require the

requested State to act inconsistently with its obligations under international agreements pursuant to

which the consent of a sending State is required to surrender a person of that State to the Court, unless

the Court can first obtain the cooperation of the sending State for the giving of consent for the

surrender".

[xliii] General Principles of Criminal Law Shaping the International Criminal Justice System' by

Professor Dr Otto Triffterer, University of Salzburg Austria. This Paper was delivered at ETHICS

European Regional Workshop in Riga Latvia 7-8 June 2006.

[xliv] Article 25(4) reads "No provision in this Statute relating to individual criminal responsibility

shall affect the responsibility of States under international law."

[xlv] See comment by Dapo Akande "The African Union's Response to the ICC's Decision on Bashir's

Immunity: Will the ICJ get another Immunity Case?" Accessed at www.ejiltalk.org. See also comment

by Goran Sluiter "ICC's Decision on Malawi's Failure to arrest Al Bashir Damages the Authority of the

Court and Relations with African Union" accessed at www.ilawyerblog.com.

[xlvi] Jan Klabbers "An introduction to International Institutional Law" Cambridge University Press

[xlvii] Decisions, Declarations and Resolutions of the 19th Assembly of African Union.

[xlviii] Ibid 45 above

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Adjusted CBA 2013-2017Documento3 pagineAdjusted CBA 2013-2017opulithe100% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Performance of Informal Contractors in KDocumento47 paginePerformance of Informal Contractors in KopulitheNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Lecture Notes On GeomorphologyDocumento100 pagineLecture Notes On GeomorphologyopulitheNessuna valutazione finora

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Irjet V4i11204 PDFDocumento3 pagineIrjet V4i11204 PDFAbhishek MishraNessuna valutazione finora

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Nca Code of ConductDocumento15 pagineNca Code of ConductopulitheNessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Physics Form 1 NotesDocumento47 paginePhysics Form 1 NotesOsmany MadrigalNessuna valutazione finora

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Cba 2017-2021Documento24 pagineCba 2017-2021opulithe100% (1)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Kenya 2010 enDocumento109 pagineKenya 2010 enopulitheNessuna valutazione finora

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Tra C Loads Used in The Design of Highway RC Bridges in EgyptDocumento11 pagineTra C Loads Used in The Design of Highway RC Bridges in EgyptNikunjNessuna valutazione finora

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Vector Analysis 6Documento14 pagineVector Analysis 6opulitheNessuna valutazione finora

- Lithosphere and GeomorphologyDocumento41 pagineLithosphere and GeomorphologyopulitheNessuna valutazione finora

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Solution of Engineering Mechanics For UCER Students 1995976039Documento18 pagineSolution of Engineering Mechanics For UCER Students 1995976039Gulshan KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- 6 329 1485758414136 140Documento5 pagine6 329 1485758414136 140kavikrishna1Nessuna valutazione finora

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- Solutions Vector AnalysisDocumento9 pagineSolutions Vector AnalysisopulitheNessuna valutazione finora

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Concurrent Force Systems: Department of Mechanical EngineeringDocumento53 pagineConcurrent Force Systems: Department of Mechanical EngineeringArmenion Mark AllenNessuna valutazione finora

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- HW2 SolutionDocumento6 pagineHW2 Solutionscarlos_6Nessuna valutazione finora

- Vector Analysis 5Documento13 pagineVector Analysis 5opulitheNessuna valutazione finora

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Mechanics of Materials 1Documento304 pagineMechanics of Materials 1opulithe100% (2)

- in The Cantilever Truss Shown in Fig. P-407 Compute The Force in Members AB, BE, and DE. FIGURE P-407Documento14 paginein The Cantilever Truss Shown in Fig. P-407 Compute The Force in Members AB, BE, and DE. FIGURE P-407ceelynNessuna valutazione finora

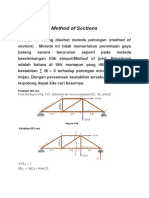

- Method of SectionsDocumento15 pagineMethod of SectionsDesti Gokil's K-AsgammaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Method of SectionsDocumento6 pagineMethod of SectionspeipeinicoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Chapter 7, Solution 1.: Fbd Frame: 0: M Σ = 0.3 m 0.4 m 900 N 0 D− = 1200 N ∴ = DDocumento177 pagineChapter 7, Solution 1.: Fbd Frame: 0: M Σ = 0.3 m 0.4 m 900 N 0 D− = 1200 N ∴ = DDivya SwaminathanNessuna valutazione finora

- Beer Mecanica de Materiales 5e Manual de Soluciones c01 y c02Documento184 pagineBeer Mecanica de Materiales 5e Manual de Soluciones c01 y c02Alejandro Sanchez100% (2)

- Problem Set 5 (Key)Documento18 pagineProblem Set 5 (Key)wheeler89210% (2)

- Engg 201 W09Documento12 pagineEngg 201 W09opulitheNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 6 Basic Mechanics PDFDocumento22 pagineChapter 6 Basic Mechanics PDFTarique AhmedNessuna valutazione finora

- Solutions ManualDocumento262 pagineSolutions Manualopulithe100% (1)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Staticschapter 3Documento205 pagineStaticschapter 3rbrackins83% (29)

- Chapter 4 - Homework Problems: Problem 4.1 Problem 4.4Documento12 pagineChapter 4 - Homework Problems: Problem 4.1 Problem 4.4daniloNessuna valutazione finora

- Strength Design of Pretensioned Flexural ConcreteDocumento19 pagineStrength Design of Pretensioned Flexural ConcreteopulitheNessuna valutazione finora

- Chuck Blazer's Court TranscriptDocumento40 pagineChuck Blazer's Court TranscriptNeville LennoxNessuna valutazione finora

- De Leon V OngDocumento7 pagineDe Leon V OngChino RazonNessuna valutazione finora

- United States Court of Appeals, First Circuit.: Nos. 75-1316 To 75-1318Documento6 pagineUnited States Court of Appeals, First Circuit.: Nos. 75-1316 To 75-1318Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Provisional OrdersDocumento45 pagineProvisional OrdersPipoy AmyNessuna valutazione finora

- PUBOFF Cipriano v. Comelec DIGESTDocumento3 paginePUBOFF Cipriano v. Comelec DIGESTkathrynmaydevezaNessuna valutazione finora

- CLJ5 - Evidence Module 3: Rule 129: What Need Not Be Proved Topic: What Need Not Be ProvedDocumento9 pagineCLJ5 - Evidence Module 3: Rule 129: What Need Not Be Proved Topic: What Need Not Be ProvedSmith BlakeNessuna valutazione finora

- Naaip PresentationDocumento15 pagineNaaip PresentationNATIONAL ASSOCIATION for the ADVANCEMENT of INDIGENOUS PEOPLE100% (1)

- Case Digests - Habeas CorpusDocumento11 pagineCase Digests - Habeas Corpusmaanyag6685Nessuna valutazione finora

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- AFGE Local 1658 and Army Tank Command 9-6-11Documento25 pagineAFGE Local 1658 and Army Tank Command 9-6-11E Frank CorneliusNessuna valutazione finora

- Volume 1 of Trial Transcript For Fleming DanielsDocumento234 pagineVolume 1 of Trial Transcript For Fleming DanielsJohn100% (4)

- Administrative Code of 1987 PDFDocumento238 pagineAdministrative Code of 1987 PDFDessa Ruth ReyesNessuna valutazione finora

- History of LRADocumento1 paginaHistory of LRAAnonymous lYBiiLhNessuna valutazione finora

- 05 - Dison vs. PosadasDocumento2 pagine05 - Dison vs. Posadascool_peach100% (1)

- APUSH Chapter 10 NotesDocumento11 pagineAPUSH Chapter 10 Notesphthysyllysm50% (2)

- Republic of The Philippines 12th Judicial Region, Branch 3 Kidapawan City RTC, CotabatoDocumento4 pagineRepublic of The Philippines 12th Judicial Region, Branch 3 Kidapawan City RTC, CotabatoClintNessuna valutazione finora

- FormDocumento6 pagineFormAdv Vineet Shukla100% (1)

- City of Batangas v. Shell G.R. No. 195003Documento8 pagineCity of Batangas v. Shell G.R. No. 195003Lorille LeonesNessuna valutazione finora

- Deborah A. LeBarronDocumento2 pagineDeborah A. LeBarronThe News-HeraldNessuna valutazione finora

- United States v. Alexander Matthews, 4th Cir. (2015)Documento4 pagineUnited States v. Alexander Matthews, 4th Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- 2 People v. YecyecDocumento8 pagine2 People v. YecyecYawa HeheNessuna valutazione finora

- Cralaw Virtua1aw Libra RyDocumento10 pagineCralaw Virtua1aw Libra RyFe GregorioNessuna valutazione finora

- United States Court of Appeals: Corrected Opinion PublishedDocumento17 pagineUnited States Court of Appeals: Corrected Opinion PublishedScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- 01 Rule112 Sec01 - Buchanan vs. Viuda de Esteban., 32 Phil. 363, No. 10402 November 30, 1915Documento6 pagine01 Rule112 Sec01 - Buchanan vs. Viuda de Esteban., 32 Phil. 363, No. 10402 November 30, 1915Galilee RomasantaNessuna valutazione finora

- 3 A Notice of DefaultDocumento3 pagine3 A Notice of DefaultEmpressInI100% (2)

- Carney Lawsuit FullDocumento39 pagineCarney Lawsuit FullMy-Acts Of-Sedition100% (1)

- Judiciary Times Newsletter 2017 Issue 02Documento11 pagineJudiciary Times Newsletter 2017 Issue 02Ade Firman FathonyNessuna valutazione finora

- Slade LJ: Jones V LipmanDocumento4 pagineSlade LJ: Jones V LipmanNicholas NipNessuna valutazione finora

- Philamlife Vs Pineda (Masiglat)Documento1 paginaPhilamlife Vs Pineda (Masiglat)Francis MasiglatNessuna valutazione finora

- Indian Penal CodeDocumento17 pagineIndian Penal CodeHarshdeep Pandey100% (1)

- Article 21 in The Constitution of IndiaDocumento3 pagineArticle 21 in The Constitution of IndiakrithikaNessuna valutazione finora

- For the Thrill of It: Leopold, Loeb, and the Murder That Shocked Jazz Age ChicagoDa EverandFor the Thrill of It: Leopold, Loeb, and the Murder That Shocked Jazz Age ChicagoValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (97)

- Hunting Whitey: The Inside Story of the Capture & Killing of America's Most Wanted Crime BossDa EverandHunting Whitey: The Inside Story of the Capture & Killing of America's Most Wanted Crime BossValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (6)

- The Edge of Innocence: The Trial of Casper BennettDa EverandThe Edge of Innocence: The Trial of Casper BennettValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (3)

- Lady Killers: Deadly Women Throughout HistoryDa EverandLady Killers: Deadly Women Throughout HistoryValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (154)

- Conviction: The Untold Story of Putting Jodi Arias Behind BarsDa EverandConviction: The Untold Story of Putting Jodi Arias Behind BarsValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (16)

- Perversion of Justice: The Jeffrey Epstein StoryDa EverandPerversion of Justice: The Jeffrey Epstein StoryValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (10)

- Just Mercy: a story of justice and redemptionDa EverandJust Mercy: a story of justice and redemptionValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (175)