Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

African Rice

Caricato da

Millenium Ayurveda0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

54 visualizzazioni22 pagineThis paper presents the botanical and historical evidence for the role of African rice (O. Glaberrima) and slaves in the crop's introduction to the Americas during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. By focusing on culture, technology, and the environment the research challenges the perspective of the Columbian exchange.

Descrizione originale:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoThis paper presents the botanical and historical evidence for the role of African rice (O. Glaberrima) and slaves in the crop's introduction to the Americas during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. By focusing on culture, technology, and the environment the research challenges the perspective of the Columbian exchange.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

54 visualizzazioni22 pagineAfrican Rice

Caricato da

Millenium AyurvedaThis paper presents the botanical and historical evidence for the role of African rice (O. Glaberrima) and slaves in the crop's introduction to the Americas during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. By focusing on culture, technology, and the environment the research challenges the perspective of the Columbian exchange.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 22

The Role of African Rice and Slaves in the History of Rice Cultivation in the Americas

Author(s): Judith A. Carney

Reviewed work(s):

Source: Human Ecology, Vol. 26, No. 4 (Dec., 1998), pp. 525-545

Published by: Springer

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4603297 .

Accessed: 26/12/2012 09:24

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

.

Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Human Ecology.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded on Wed, 26 Dec 2012 09:24:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Human Ecology, Vol. 26, No. 4, 1998

The Role of African Rice and Slaves in the

History of Rice Cultivation in the Americas

Judith A. Carneyl

This paper presents the botanical and historical evidence for the role of

African

rice (O. glaberrima) and slaves in the crop's introduction to the Americas

during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. By focusing on culture,

technology, and the environment the research challenges the perspective of the

Columbian Exchange that emphasizes the

diffusion

of crops to, rather than

from Africa, by Europeans. The evidence presented in this paper suggests a

crucial role for glaberrima rice and slaves in the introduction of African crops

to the Americas.

KEY WORDS: rice; slaves; technology transfer; Columbian exchange.

If Africa appears to have provided little for other continents, it is because Africa

is only just beginning to be known. (Porteres, 1970, p. 43)

INTRODUCTION

A recent National Research Council (NRC) book, Lost Crops of Africa,

draws attention to the potential

of the continent's little-known indigenous

crops for improving regional and global food supplies. Featured promi-

nently among the 2000 native grains, roots, and fruits utilized as food sta-

ples is African rice (Oryza glaberima), "the great red rice of the hook of

the Niger" (1996, p. 17). One of just two domesticated species of the Oryza

genus, glaberima is scarcely known outside Africa, and even there has wit-

nessed steady replacement this century by higher-yielding Asian sativa va-

rieties. Compared to the Asian species, glaberima is characterized by its

red hulls, small size, smooth glumes and tendency to break in mechanized

milling. Because glaberima does not readily cross with sativa, the African

'Department of Geography, 1255 Bunche Hall, UCLA, Los Angeles, California 90095-1524;

e-mail: camey@geog.ucla.edu

525

0300-7839/98/1200-0525$15.00/0

?

1998 Plenum Publishing Corporation

This content downloaded on Wed, 26 Dec 2012 09:24:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

526 Carney

rice's greater tolerance to

salinity,

drought, and flooding is receiving in-

creasing plant breeding attention (Sano, 1989; Harlan, 1995; NRC, 1996).

Yet despite its plant breeding potential, there are other compelling

reasons for a research focus on glabenima. A review of the botanical, his-

torical, and geographical literature on the

history

of rice cultivation in the

Americas may hold the clue to issues meriting additional research attention,

namely that: (i) glabemima may have served as the initial rice grown in

many regions located along the western rim of the Atlantic basin; and (ii)

West African slaves, familiar with the techniques of its cultivation, played

a crucial role in adapting the crop to diverse New World environments.

This overview of rice history in the Americas raises several issues that

bear on prevailing conceptions of the "Columbian Exchange," the period

of unparalleled crop exchanges from the sixteenth through eighteenth cen-

turies. Scholarship on the Columbian Exchange has long emphasized the

economically valuable crops of American, Asian, and European origin; the

role of Europeans in their global dispersal; and thus, the diffusion of crops

to, rather than from, Africa (Jones, 1959; Ribeiro, 1962; Miracle, 1966;

Crosby, 1972; Kloppenburg, 1990). The slight attention accorded African

crops in this scholarship is related to two factors: the minor role of African

domesticates like okra, cowpeas, yams, pearl millet, and sorghum in food

and plantation economies, and the longstanding belief that rice was solely

of Asian origin.

Recent historical research on the beginnings of rice cultivation in the

U.S. South, however, challenges the view that Africa contributed little more

than labor to the agricultural history of the Americas (Wood, 1974a; Lit-

tlefield, 1981; Hall, 1992; Rosengarten, 1997). In extending the emphasis

on rice history to Latin America, through a preliminary integration of bo-

tanical and historical materials, this paper provides additional support

for

the argument that glaberima and slaves played a crucial role in the expan-

sion of rice cultivation in the Americas during the early period of the At-

lantic slave trade. In so doing, this article directly engages broader issues

of technology transfer, indigenous knowledge, and the agency of slaves in

adapting a preferred dietary staple to diverse New World environments.

The paper is divided into four parts. The first section addresses bo-

tanical scholarship on rice origins, with emphasis on the discovery during

the twentieth century that rice domestication occurred in West Africa in-

dependently of Asia, long viewed as the sole center of the plant's domes-

tication. The next section shifts to the U.S. where historical and

historical-geographical research from the 1970s first claimed African agency

in adjusting rice cultivation to the South Carolina swamps, the crop that

sustained the South's most lucrative plantation economy. The third section

focuses on the role of the Cape Verde Islands as a pioneering agricultural

This content downloaded on Wed, 26 Dec 2012 09:24:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Rice Cultivation in the Americas 527

M A U R I TA N I A MALI

SECONDARY

PRIMARY CENTER

I

H A X * .S

~~~~N I G E R

THEGAA

GUINE

IN K FASO'.'

BISSAU G

AEN

S

~lE RRA

Atatc Ocea

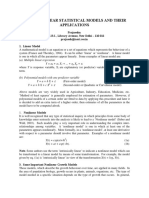

Fig. 1. Indigenous African rice domestication area.

experiment station for African crops and as an entrepot for the diffusion

of rice to Brazil. The last section presents the botanical and historical evi-

dence for an early presence of glabemima rice in the Americas.

BOTANICAL SCHOLARSHIP ON AFRICAN RICE

Domestication of African rice occurred more than 3000 years ago in

the region from Senegal to the Ivory Coast, long before any navigator from

Java or Arabia could have introduced rice to Madagascar or the East Af-

rican coast (Fig. 1) (Porteres 1976; NRC, 1996, p. 23). From the eighth to

the sixteenth centuries Arab and European commentaries mention rice cul-

tivation along the inland delta of the Niger River and the West African

coast as well as the frequent purchases of surpluses by Portuguese mariners

(Ribeiro, 1962; Lewicki, 1974; Littlefield, 1981; Brooks, 1993). During the

Atlantic slave trade rice surpluses contributed to provisioning slave ships

bound for the Americas (Carney, 1996a,b). Yet, despite numerous com-

mentaries on West African rice from the earliest period of contact, well

into the twentieth century scholars routinely assigned rice an Asian origin,

and attributed its diffusion to Africa to Arab and Portuguese traders

(Rochevicz, 1932; Ribeiro, 1962; Grime, 1976). As a result of the bias in

scholarship, researchers failed to consider the indigenous knowledge base

of African rice production systems and its potential linkage to the cereal's

appearance in the Americas.

This content downloaded on Wed, 26 Dec 2012 09:24:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

528 Carney

Linnaeus (1707-78) registered only the Asian sativa rice in his botanical

classification of the Otyza species, a position uncritically followed in 1866 by

de Candolle (1964) in his compendium on the origin of cultivated plants. The

Asian origin of rice remained unquestioned even with the earliest botanical

collections of rice in West Africa during the nineteenth century. French bota-

nist Leprieur attributed the rice collections he made in Senegal between

1824-29 to the sativa species as did Edelstan Jardin, who collected rice from

islands off the coast of Guinea Bissau in 1845-48 (Chevalier, 1937a; Porteres,

1955a). But an examination of the Jardin collection by Moravian botanist

Steudel led him to conclude in 1855 that the samples represented a rice spe-

cies distinct from Asian sativa, which he named Oryza glaberima for its

smooth hulls. His research, however, stopped short of arguing that glaberima

was of African origin. Only at the turn of the century did botanists working

in the French West African colonies suspect an African origin for the wide-

spread cultivation of a red-hulled rice with distinctive characteristics. This

suspicion led to the discovery of Steudel's research conducted half a century

earlier, and a reexamination of the Leprieur herbarium collection, which also

showed the presence of glaberima (Porteres, 1955a).

As the French began advancing the hypothesis for an indigenous West

African rice from 1914, research interest in glaberima lagged within the

international scientific community (Chevalier and Roehrich, 1914; Cheva-

lier, 1932; Rochevicz, 1932; Chevalier, 1936, 1937a,b; Viguier, 1939). The

noted Russian geneticist Vavilov (1951), for instance, whose pathbreaking

research on indigenous centers of plant domestication received widespread

attention in the 1920s, made no mention of glaberima, assigning rice solely

an Asian origin.

But over the following decades French botanists increased the research

momentum on glaberrima. They showed that Asian rice had not yet reached

the Nile and Egypt during geographer Strabo's time (ca. first century A.D.),

thereby making it highly unlikely that diffusion across the Sahara could ex-

plain the widespread presence of rice in diverse environments of the French

Sudan from the eighth century,

when it receives

commentary by

Arab schol-

ars (Lewicki, 1974, p. 34). Strengthening

the

hypothesis

for an African

origin,

botanical collections revealed several wild relatives of glaberima in West Af-

rica without locating any wild sativas (Rochevicz, 1932, p. 950).

While French scholars noted a Portuguese role in

introducing

sativa va-

rieties from Asia to West Africa during the sixteenth century, they empha-

sized the continued dominance of glaberima in the first decades of

colonialism (Chevalier, 1937a,b; Viguier, 1939; Pelissier, 1966; Porteres,

1976). Their botanical research on rice gained momentum as metropolitan

concern grew over the food shortages and famines that were accompanying

the colonial emphasis on export crops. Rice, cultivated on swamp land un-

This content downloaded on Wed, 26 Dec 2012 09:24:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Rice Cultivation in the Americas 529

suitable for peanuts and cotton, received increasing attention as a means to

alleviate food crises (Carney, 1986). During the 1930s the potential of rice

as an export crop proved increasingly significant with the establishment of

rice research stations throughout the West African rice zone (Chevalier,

1936; Baldwin, 1957; Cowen, 1984). The research stations emphasized

shorter duration sativa varieties more amenable to irrigation, double-crop-

ping and mechanized milling. Sativa varieties produced higher yields with

transplanting, broke less than glaberrima with mechanized milling, and were

whiter in color. Thus, they suited the commercial objectives and consumer

preferences of potential European export markets (Chevalier, 1936, 1937b;

Grist, 1968).

In the 1950s, as sativa cultivation was steadily displacing glaberrima,

French botanist Porteres (1976) identified the African center of rice do-

mestication. Following methods pioneered by Vavilov, he located the inland

delta of the Niger River as the primary center of glaberima domestication

with secondary centers of the crop's speciation developing along floodplains

in Senegambia and under rainfall in the mountains of Guinea Conakry.

By the 1970s the pioneering French botanical research was known widely

within the international scientific community, which accepted the conclusion

that 0. glaberima was indeed an independent rice species of African origin.

The legacy was the publication in 1974 of two pathbreaking books by histo-

rians. Working on previously untranslated Arab references to West African

food systems during the Middle Ages, Polish historian Lewicki (1974) docu-

mented the antiquity of indigenous West African rice cultivation. During the

same year U.S. historian Peter Wood (1974a) argued that the history of rice

cultivation on plantations in South Carolina was likely of African origin.

AFRICAN AGENCY IN ESTABLISHING RICE CULTIVATION IN

SOUTH CAROLINA

Until historian Wood's (1974a) research on the evolution of the rice

plantation system in colonial South Carolina, there was no hint that rice cul-

tivation in the U.S. might owe its genesis to African slaves.

Noting

the

ap-

pearance of rice cultivation in tandem with slavery from the earliest

settlement period (1670-1730), the unfamiliarity of the colony's English and

French Huguenot planters with cultivation techniques, and glaberrima domes-

tication in West Africa, Wood attributed the crucial skills involved in the

plantation rice system to West African slaves already familiar with its plant-

ing.2 Rice formed the dietary staple of millions swept into the Atlantic slave

2Archival comments on rice cultivation in South Carolina are evident by the 1690s (Wood,

1974a). Nothing suggests any planter knowledge of Asian rice systems.

This content downloaded on Wed, 26 Dec 2012 09:24:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

530 Carney

trade, and the African rice region contributed more than 40% of the slaves

delivered to colonial South Carolina (Wood, 1974a; Richardson, 1991).

Littlefield (1981) advanced Wood's hypothesis by drawing attention to

the antiquity of rice production in West Africa, to European interest in

the techniques of its cultivation during the Atlantic slave trade, and to

planter preference for slaves with rice-growing

experience.

He identified

as of African origin the floodplain rice cultivation system found along the

Upper Guinea coast, where groups like the Baga perfected methods to de-

salinate fertile mangrove soils for rice cultivation. By enclosing plots with

earthen palisades or embankments and constructing small canals, the Baga

could retain water on the fields or remove it through gravity flow at low

tides (Littlefield 1981, pp. 80-98). As analagous techniques developed on

Carolina floodplains, Littlefield showed that a rice system long attributed

to planter ingenuity was in fact an important part of the agronomic heritage

of slaves from the West African rice region. But subsequent elaboration of

the Wood-Littlefield hypothesis suffered from the meager documentation

on rice history during the early colonial period and the fact that accounts

were written by those who enslaved. Thus, planters claimed that they were

experimenting with growing rice in multiple environments, a task that

would in fact have been performed by their slaves.

Using a perspective focused on environment and material culture,

Carney (1993, 1996a,b) shifted research attention from rice as a cereal to

rice as a crop, a perspective which requires thinking about rice as a suite

of distinct production systems with specific techniques of landscape ma-

nipulation. Rice more than any other cereal requires human beings to act

as geomorphological agents in nature through the process of transforming

swamps to productive paddy fields. The historical record in West Africa

affirms at the beginning of the Atlantic slave trade the existence of three

major rice cultivation systems which can be distinguished by

micro-envi-

ronment, agronomic practices, and techniques of soil and water manage-

ment (Carney, 1993, 1996a).

The existence of these three rice systems-

rainfed, inland swamps and tidal floodplains-is documented in South

Carolina by the 1730s, within decades of the crop's introduction to the col-

ony (Carney 1993, 1996a).3

Typical of rice cultivation in Africa but not Asia, was the absence of

transplanting on Carolina floodplains. Also evident were parallel

tech-

niques of production

like water control by sluices constructed from hol-

lowed tree trunks, a comprehensive understanding of tidal ebb and flow

to prevent field overflooding while enabling cultivation in areas occasionally

3The introduction of rice to South Carolina occurred during the 1690s (Salley, 1919).

This content downloaded on Wed, 26 Dec 2012 09:24:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Rice Cultivation in the Americas 531

menaced by saltwater intrusion, and the widespread use of long-handled

hoes for weeding (still used in African rice farming).4

But rice could become a valued export crop only when it was processed

to remove the indigestible hulls.5 Until the advent of water-driven mills dur-

ing the second half of the eighteenth century, rice milling was performed by

hand in the African manner with a wooden mortar and pestle (Wood, 1974b;

Carney, 1996b). The hulls were removed through winnowing the cereal in

fanner baskets, woven in the same way as those for analagous purposes in

the Senegambian rice area of West Africa (Rosengarten, 1997).6

A focus on the environmental aspects of rice cultivation and the material

culture of infrastructure and milling thus brings new insights to the recovery

of perhaps a significant narrative of the African diaspora. The next section

explores the crucial role of the Cape Verde Islands as transfer points of slaves

and cropping systems between West Africa and the Americas.

THE CAPE VERDE ISLANDS AND AFRICAN RICE

There are several reasons that suggest African rice played an impor-

tant role in establishing the crop in the Americas. The first involves a re-

view of the history of rice in the Cape Verde Islands while the second,

addressed in the following section, examines the documented presence of

glabenima in regions of African settlement in the Americas where cuisines

based on rice retain enduring significance.

From the mid-fifteenth century, settlement of the Cape Verde Islands

and especially Santiago, unfolded amid an active trade with West African

coastal peoples for waxes, hides, indigo, foodstuffs, salt, and slaves (Brooks,

1993, pp. 130, 279). Since the ninth century the littoral and off-shore islands

4The task labor system, another feature of plantation rice cultivation in South Carolina, may

also provide indirect evidence for African agency in the crop's establishment. This labor sys-

tem, found only on rice plantations, assigned a daily field task for completion, which for the

robust and healthy could mean a shortened labor day. In the more pervasive gang labor

system of plantation slavery, bondsmen worked daily from dawn to dusk. The unusual ap-

pearance of the distinctive task labor system on rice plantations perhaps represents the resi-

due of a complex pattern of negotiation in establishing Carolina rice plantations in which

slaves provided the know-how to grow rice in exchange for circumscribed demands on their

daily labor (Carney, 1993).

5Rice consumption depends upon removing the hull that encloses the grain without breakage

in the process. Burkhill (1935ii, p. 1601) summarizes the problem posed by rice milling by

comparing its processing with that of other cereals: "European milling machinery for rice

could not be adapted simply from that used for other cereals, for in the milling of wheat

the object is to get the finest of powders; but in the milling of rice, the object is to keep

the grain whole as much as possible."

6Rosengarten (1997, pp. 273-311) argues that the baskets of native Americans were plaited

and twilled, not the coiled type subsequently used for rice winnowing, which was and remains

identical to that found in the Senegambian rice region.

This content downloaded on Wed, 26 Dec 2012 09:24:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

532 Carney

14'

8~~~~~

NE GA L M A L l

GINEA

0

6)

~ ~ ~ G

l ~ ~~~ v E e

l / A

16~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

'

I'a, 4' PmtL . 4 'e

Fig. 2. Location of initial European trading networks with West African rice societies, ca.

sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

of the Upper Guinea Coast from Guinea Bissau to Sierra Leone had served

as an important crossroads for the long-distance trade in salt (Fig. 2) (Brooks,

1993, p. 80). Wet rice cultivation supported this vast trading network, but the

crop only emerged important as a trade good with the arrival of the Portu-

guese. By 1479, the principal ethnic groups of the region-the Baga, Diola,

Balanta, Bullorn/Sherbro, and Temni-were already marketing their dietary

staple to the Portuguese (Rodney, 1970, p. 21; Carreira, 1984, pp. 27-28;

Brooks, 1993, pp. 276-296).7 Their prominence in initial African-Portuguese

trading networks, however, was not to endure; by the end of the eighteenth

7The commercial lingua franca of this Biafada-Sapi trading network formed from related lan-

guages of the West Atlantic linguistic group. The groups mentioned in the text are charac-

terized by wet rice cultivation, loosely-grouped acephalous societies with weak social

stratification, animism, and matrilineal descent patterns. Early references to them appear in

accounts by Eustache de la Fosse (ca. 1479), Valentim Fernandes (ca. 1506-10), Andre Al-

vares de Almada (ca. 1594) and Andre Donelha (ca. 1625) (Rodney, 1970, pp. 6-45, 112;

Brooks, 1993, p. 80, 275-279).

This content downloaded on Wed, 26 Dec 2012 09:24:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Rice Cultivation in the Americas 533

century, hundreds of thousands of wet rice farmers had become captives of

the Atlantic slave trade (Brooks, 1993, pp. 174, 292-296).

At the beginning of the sixteenth century, Valentim Fernandes, drawing

upon earlier mariners' accounts, ascribed the introduction of both rice and

cotton cultivation in Santiago to the wet rice area of the Guinea coast

(Ribeiro, 1962, p. 147). The emergence of a sugar cane and grazing econ-

omy on the island during this period proceeded in tandem with the culti-

vation of African domesticates like yams, sorghum, millet, rainfed and

swamp rice (Brooks, 1993, pp. 139-147; Ribeiro, 1961, pp. 143-145; Dun-

can, 1972, p. 168; Blake, 1977, pp. 91-92).

Thus, by the sixteenth century, the initial period of the Columbian

Exchange, the Cape Verde Islands were already serving as an ex-officio ag-

ricultural research station for plant experimentation. Europeans ships regu-

larly provisioned there for voyages to the Americas (Ribeiro, 1962; Duncan,

1972; Brooks, 1993). The return voyages served to introduce American cul-

tivars, like maize and manioc, to West Africa, but these were preceded by

an active rice trade, well in place by 1514 (Blake, 1977, pp. 91-92). Rice

appears on cargo lists of ships departing Cape Verde in 1513-15 (Ribeiro,

1961, pp. 146-147). In 1530, just 30 years after Cabral claimed Brazil for

Portugal, a ship left Santiago, for Brazil, carrying rice seed in its cargo

(Brooks, 1993, p. 149).

In subsequent decades other vessels delivered seed rice to the state

of Bahia, an important locus for the sugar plantation system in Brazil's

Northeast (Ribeiro, 1962, pp. 143-144; Duncan, 1972, p. 167). In 1587, Ba-

hian planter, Gabriel Soares de Sousa, noted the important role of the

Cape Verde Islands for animal and crop introductions to Brazil. He attrib-

uted the widespread cultivation of rainfed and swamp rice to seed rice

brought from Cape Verde, while

noting slave preference for yams and foods

of African origin, the use of mortar and pestle for food processing, and

the triumph of African dietary preferences among the slave

population

(Ribeiro, 1962, pp. 152-156).

Thus, several facts dating from the fifteenth century raise questions

about the longstanding view that rice origins in the Americas derived

solely

from Asian varieties. These include the antiquity of rice cultivation along the

Upper Guinea Coast, Portuguese settlements on African islands and the

coast that were dependent upon African food surpluses, the widespread ex-

change of rice between West Africa and the Cape Verdean archipelago, and

its early cultivation on Santiago (Rodney, 1970, pp. 74-88; Carreira, 1984,

pp. 47-62; Brooks, 1993, pp. 147, 260). This active trade in rice resulted dur-

ing the sixteenth century in repeated deliveries of rice seed to the Brazilian

plantation sector. While trading contact with Asia was developing over this

same period, the more frequent voyages between the African coast and Cape

This content downloaded on Wed, 26 Dec 2012 09:24:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

534 Carney

Verde, as well as their geographical

proximity

to the Americas suggest a key

role for African rice in the crop's diffusion across the Atlantic.8

Yet Portuguese scholarship mirrored the generalized view that Africa

provided little of value to the global food larder (Figueiredo, 1926; Ribeiro,

1962). One leading Portuguese scholar assigned the early cultivation in

Cape Verde of the "inferior and miserable food staples," sorghum and findo

(Digitaria exilis), a West African origin; however, the more significant cul-

tivation of rice in the archipelago and along the West African coast he

attributed to Portuguese mariners introducing rice culture from India

(Ribeiro, 1962, pp. 27, 49). Apparently unaware of the French botanical

scholarship that was documenting the existence of an independent African

rice species, Ribeiro's research nonetheless echoed the more generalized

view that Asian rice spearheaded the crop's diffusion throughout the At-

lantic basin.9

But as the historical research on South Carolina reveals, rice cultivation

depends upon knowing how to mill the grain without breakage. In failing to

assign rice an African origin, Ribeiro missed an important linkage. Puzzled

by the early diffusion of the African mortar and pestle rather than the Por-

tuguese hand mill for cereal processing in both Santiago and Brazil, Ribeiro

emphasized the suitability of the mortar and pestle for milling sorghum, an

African crop (1962, p. 23). But the Portuguese device would permit sorghum

milling, although not rice. The diffusion of rice culture throughout the At-

lantic basin depended crucially therefore upon an appropriate device for its

processing. Until the second half of the eighteenth century this was the mor-

tar and pestle, a device that requires skill in striking the rice without breaking

the grain into fragments (Carney, 1996b). In not considering the African ori-

gin of rice, Ribeiro missed the significance of slaves in diffusing mortar and

pestle processing techniques to the Arnericas.10

8Curtin (1984, p. 143), for instance, argues that during the period from 1500-1634, only 470

Portuguese ships returned from voyages to the Indian Ocean, less than four per year.

Despite acknowledgment of an African rice species, the assumption that Asian rices displaced

African varieties along the West African coast during the mid-fifteenth century is still widely

held. However, Richards (1996, pp. 211-212) argues that documentation for significant re-

placement of glabemima by sativa rices is evident only from the colonial period in the late

nineteenth century.

1?During this period, Asian rice-growing societies used several types of devices for processing

rice. These included the mortar and pestle as well as a foot-operated fulcrum to which a

pestle was attached to one end. Raising the fulcrum with the foot allowed the pestle to fall

into a mortar (namely, a hole in the ground or floor), thereby removing the grain's hulls.

This device was widespread in Asia (Grist, 1968, p. 216a) and is described as being used in

Japan in The Tale of the Genji, written about 1000 years ago. But the Asian device would

not have worked for processing glaberima rice which, as the NRC (1996) study discusses,

breaks more readily with mechanical milling. The potential for examining the relationship

between migration, rice cultivation, and the technology for the crop's milling becomes evident

by contrasting specific ethnic migrations of rice farmers to the Americas. For example, in a

rice-growing region of Belize where descendants of Indian indentured laborers grow rice

This content downloaded on Wed, 26 Dec 2012 09:24:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Rice Cultivation in the Americas 535

THE DIFFUSION OF RICE CULTIVATION TO THE AMERICAS

Botanists spearheaded interest in the history of rice cultivation in Bra-

zil. The crop's presence so early in the country's settlement in fact led one

Brazilian botanist, Hoehne (1937), to claim that rice cultivation preceded

the arrival of Europeans in 1500. Interpreting reports from the sixteenth

century on Amerindian offerings of rice to the Portuguese as evidence for

its domestication, subsequent research showed that this was a wild rice spe-

cies, not the sativa he claimed (Oliveira, 1993).11 While Hoehne's views on

pre-Columbian rice cultivation proved incorrect, his work did provide in-

dependent confirmation for rice cultivation in Brazil during the sixteenth

century, about a 100 years earlier than its sustained cultivation in the U.S.

South.12

Historical documents pertaining to Brazil prior to the mid-eighteenth

century make frequent reference to rice, especially a red-hulled species,

over a broad area from the Northeast to the Amazon (Primeiro, 1818;

Marques, 1870; Chermont, 1885; Alden, 1959; Nunes Dias, 1970; Viveiros,

1895; Barata, 1973; Hemming, 1987; Oliveira, 1993; Acevedo, 1997). Red

rice again surfaces in commentaries during the second half of the eight-

eenth century, when a rice plantation system developed in the eastern Ama-

zon with backing from metropolitan capital. The objective was to develop

Amazonian export markets to Portugal and thereby reduce dependency on

Carolina rice imports as the American colonies headed into the Revolu-

tionary War (Nunes Dias, 1970; Acevedo, 1997). This led to the creation

from the 1760s of tidal-irrigated rice plantations in the Amazonian states

of Amapa, Para, and Maranhao, the introduction of high-yielding "Carolina

white" rice seed (a sativa variety), water mills for rice processing, the import

of more than 25,000 slaves (many from the rice-growing region of Guinea

Bissau), and, in 1767, the first

exports

of milled rice to Portugal (Primeiro,

1818, p. 192; Gaioso, 1970; Klein, 1982).

But the continued cultivation of red rice aroused official concern. In

a 1772 decree, the Portuguese administration mandated a year's jail

sen-

tence and fine for whites planting the red rice and 2 years of imprisonment

for slaves and Indians who did (Marques, 1870, pp. 435-436; Barata, 1973;

Acevedo, 1997). While the reasons for this legal action remain unclear, it

may suggest that the red variety was a glabenima, which breaks more easily

in milling (NRC, 1996) and when mixed with the improved variety, would

alongside their Afro-Belizean neighbors, striking differences are evident in milling. The mor-

tar and pestle is used by the latter, while the former rely upon the fulcrum processing method

known to their nineteenth-century forebears (Carney, fieldwork).

"This was likely 0. glumaepatula (Oliveira, 1993).

Rice was planted in Virginia in the period from 1622 to 1647 but failed to develop into a

plantation crop (Gray, 1958, pp. i, 26).

This content downloaded on Wed, 26 Dec 2012 09:24:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

536 Carney

have resulted in a higher percentage of broken rice and thus lower prices

in European markets.

African rice may also figure in discussions of early varieties planted

in the U.S. South. "Guinea rice" is listed among the initial varieties grown

by slaves in their gardens in South Carolina, the toponym suggesting a West

African origin (Drayton, 1802; Allston, 1846). A cultivated red rice is re-

corded by Lawson in 1709 (1967, p. 729) and in 1731 (Salley, 1919, pp.

10-11). In another area of plantation slavery, Surinam, the Dutch governor

noted in 1750 the advantages of rice varieties cultivated there compared

to one type found in South Carolina: "the rice in Essequibo has not the

red husk which gives so much trouble in Carolina to get off" (Oka, 1961,

p. 21). This may well indicate the advantages of sativa over glaberrima va-

rieties in milling. Certainly by the mid-eighteenth century, rice export mar-

kets were based on Asian varieties. The high-yielding Carolina "white" and

"gold" that made the colony's production world-famous and which were

introduced to the Amazon, were sativa varieties (Salley, 1919).

0. glaberrima was certainly introduced to Georgia in 1790 by Thomas

Jefferson, whose request for rainfed rice varieties from slave merchants

resulted in a shipment of seed rice from Guinea Conakry. Jefferson asked

for rainfed varieties, hoping to stimulate upland rice planting, which

would reduce the death toll of slaves exposed to malarial floodplain cul-

tivation (Betts, 1944; Peterson, 1984).13 The merchants' descriptions of

the African upland rice systems echo those of Dutch geographer, Olfert

Dapper, who noted 150 years earlier similar features and the short-du-

ration characteristics that distinguish glaberrima rice (Richards, 1996, pp.

214-222).

Archival evidence from South Carolina confirms the cultivation of mul-

tiple varieties of rice from the 1690s, some definitely of Asian provenance,

others possibly from Africa (Salley, 1919). The dominance of the high-yield-

ing sativa varieties in plantation production from the mid-eighteenth cen-

tury, undoubtedly contributed to the disappearance of earlier varieties

which may have included glaberrima. Since upland

rice was no longer

cul-

tivated by the time of the American Revolution, Jefferson had to reintro-

duce varieties from West Africa. But his emphasis on rainfed varieties failed

to alter the course of floodplain rice expansion and they, too, disap-

13In fact, Jefferson's famous quote, "The greatest service which can be rendered any country

is to add an useful plant to its culture," was made in partial reference to rice. He regarded

the olive tree and the introduction of dry (rainfed) rice cultivation into South Carolina of

equal importance as writing the Declaration of Independence and freedom of religion (Betts,

1944, p. vii). Jefferson attributed the lack of success in diffusing this African rainfed variety

to the fact that there were "not . . . the conveniences for husking it," perhaps an indirect

reference to the mechanized milling systems that had replaced the earlier mortar and pestle,

more suitable for glabemima milling (Betts, 1944, p. 381).

This content downloaded on Wed, 26 Dec 2012 09:24:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Rice Cultivation in the Americas 537

peared.14 Displacement of glabemima from initial cultivation sites in the

Americas, ignorance until well into this century of the existence of a sepa-

rate rice species in Africa, and the subsequent focus of scholarship on ex-

port crops and sativa varieties, all contributed to the broader research

failure to consider the linkage of rice introduction to Africa and slaves.

That glabermima crossed the Atlantic during the period of the slave trade

is not in doubt since French botanists recovered glaberima varieties (the

hulls smooth and of a red-black color) in Cayenne (French Guiana) during

the 1930s and from a former sugar and indigo plantation area of El Sal-

vador during the 1950s (Vaillant, 1948; Porteres, 1955b,c, 1960; Richards,

1996, p. 218). But few scholars outside botany took notice of their findings.

The glaberima reported in Cayenne was collected from descendants

of escaped slaves (maroons) who from the 1660s fled coastal sugar plan-

tations for freedom in the rainforest (Price, 1983). The rainfed varieties

from Cayenne found by Vaillant (1948) were examined by Porteres

(1955b,c, 1960) and determined identical to others collected by the French

in Guinea Conakry, Liberia, and the Ivory Coast, where they are known

as "gbaga, baga, or bagaye" after the Baga with whom they remain indelibly

associated. Even though the Baga subsequently disappeared from many

West African areas planted to these varieties, their role as expert rice farm-

ers survived in the varietal name. Their farming practices also endure in a

detailed description and sketch of the Baga rice cultivation system re-

corded, ca. 1793, by a slave ship captain who observed them in Guinea

Conakry (Fig. 3). The discovery of Baga varieties of glaberima rice in Cay-

enne bears witness to their role during slavery in pioneering the crop in

the Guianas.15

The significance of rice as a foodstaple among maroon communities

of the Guianas was already evident during the eighteenth century when

European mercenaries were sent to recapture them; maroons frequently

cultivated rice in forest clearings and inland swamps (Price and Price, 1992).

The cereal's importance in maroon history is captured in the legends of

their descendants (Hurault, 1965; Price, 1983). In the area of Cayenne

where Vaillant found the Baga varieties, the maroons claimed that rice

14Early U.S. collections from the twentieth century do not indicate the presence of glabemima

varieties (Richards, 1996).

15From the sixteenth century, the Dutch began establishing trading posts in Baga areas for-

mally dominated by Portuguese mariners (Carreira, 1984, pp. 27-28; Brooks, 1993, p. 276).

Dutch merchant fleets increasingly dominated trading networks to Brazil and took over direct

trade to Brazil from 1584. By 1621, one-half to two-thirds of the trade from Europe to Brazil

was transported in Dutch ships (Boxer, 1965, p. 23). The Dutch plantation economy of Suri-

nam, which dates to about 1630, was the outcome of the failure of a similar attempt to

establish a foothold in Brazil (Boxer, 1965). On the export of slaves from the rice-growing

region of Guinea Bissau to Brazil, especially the Amazon during the eighteenth century, see

Boxer (1969, pp. 192-3) and Vergolino and Figueiredo (1990, pp. 49-51).

This content downloaded on Wed, 26 Dec 2012 09:24:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

538

Carney

<N X~

-~~~~~~~~~~ ;;** -- ^*

r~ ~~~~~~~~~~A Jr

t

w-

/g,

~= a

XA

X MS _ i

Fig.

3. Illustration and

description

of

Baga

rice cultivation in

Captain

Sam Gamble's

jour-

nal, ca. 1793. In Littlefield

(1981, p. 94). Reprinted

with

permission.

originally

came from Africa, brought by

female slaves who

smuggled

the

grains

in their hair

(Vaillant, 1948, p. 522).

Yet, despite

the

crop's early

association in the Guianas with slaves and

maroons, little is known about the initial

history

of rice cultivation in the

region.

Several books mention that rice was

being planted by

ex-slaves

prior

This content downloaded on Wed, 26 Dec 2012 09:24:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Rice Cultivation in the Americas

539

1ORJH -

/A IQ ER'I Cil

A FRICA A

B d - 2et4r

Srina

L E G E N D r6ayepn,

0. glaberrina found K' .

in botanical collections |J }

0 glaberrima suspected A

from historical evidence AME

RI~1

70 Judith Ca(ey, 1997

Fig. 4. Areas of documented and suspected presence of 0.

glabemima.

to the arrival of the Javanese and Indian indentured laborers who estab-

lished it as a cash crop between the 1870s and 1930s

(Panday, 1959; Lunig,

1969) but little else is said. A

great deal more archival research is needed

on the food systems of plantation economies.

Botanical collections of glabenima document its

presence

in two loca-

tions of the Americas,

while archival materials

suggest

it was

grown

else-

where. These documented and

suspected

locales of

glaberima

introduction

are presented in

Fig. 4. Whether

glaberima proved

the initial rice

variety

brought across the Atlantic

may

never be known.

However,

the evidence

from this review of archival and botanical sources indicates that

glaberima

was in fact introduced to the Americas

during

the

period

of the Atlantic

slave trade.

CONCLUSIONS

In 1637, the Dutch launched an expedition to northeast Brazil to de-

velop its colony at Pernambuco. Among the savants

accompanying the

gov-

ernor-designate, Count Maurits of

Nassau, was the Dutch

physician,

Willem

This content downloaded on Wed, 26 Dec 2012 09:24:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

540

Camey

Piso, whose 7-year stay resulted in the first truly scientific study of the ge-

ography and botany of Brazil. While rice interested Piso for its presumed

medical properties, his account indicates that the crop was already culti-

vated in Brazil by the time of Dutch settlement. Piso's compendium also

mentions the planting of several other crops, like okra and ginger, which

he claimed came to Brazil from Angola (Piso, 1957).

As plantation slavery consolidated over the next centuries, the role of

slaves in adapting African crops to diverse environments of the Americas

faded from commentaries. Trying to recapture elements of that history cen-

turies later demands a multidisciplinary perspective, particularly additional

research in botany, historical archaeology, and the archives of countries of

the Americas where rice cultivation developed.

A crucial research need is to examine existing germplasm collections

in key rice-growing countries (e.g. Brazil, Surinam, and Cuba) to detect

the presence of glaberima. Given the historical significance of maroons in

these areas and the enduring significance of rice cultivation among their

descendants, collections may well include African rice. A series of proce-

dures would facilitate species identification: glaberrima can be differentiated

from sativa, after 3-4 weeks' growth, by the shape of its ligules (Duncan

Vaughan, personal communication); alternatively, the two species can be

identified through genetic analysis.16

A second research need addresses the field of historical archaeology.

While glaberrima has been found and dated in

archaeological excavations

in Niger, West Africa (McIntosh and McIntosh, 1993), no

archaeological

research to date has sought to locate African rice in the Americas (Leland

Ferguson, personal communication). Early species planted in the Americas,

however, should be well preserved in the

perpetually wet soils of rice re-

gions. A well-designed archaeological research

program should uncover rice

samples that in turn can be

subjected

to

phytolith analysis,

a

technique

that enables identification of rice

species

and varieties.17 Historical archae-

ological research combined with

paleo-ethnobotanical phytolith analysis

16A recommended procedure is to make a preliminary sorting of germplasm material on the

basis of color, since glabemima is of red or red/purple-black hue. Promising rice varieties can

then be outgrown in the field with suspected glaberima samples subsequently subjected to

the more expensive genetic analysis. Note that more than 2000 rice varieties were collected

in Brazil during the 1970s and 1980s. Of these, about 5% possess the phenotypic glaberrima

color (Fonseca, personal communication). However, this color can also indicate degeneracy

in the seed of certain sativas (Vaughan, personal communication).

17Phytolith analysis examines the silica signature that distinguishes all grasses (Pearsall, 1989;

Pearsall et al., 1995; Zhao, et al., 1998). A pioneer in refining the techniques, Pearsall has

been working with phytolith analysis of wild and domesticated Asian rice species and has

identified species as well as varieties. She believes that such techniques are also capable of

distinguishing Asian from African rice, although the basic research has not yet been done

(Deborah Pearsall, personal communication).

This content downloaded on Wed, 26 Dec 2012 09:24:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Rice Cultivation in the Americas 541

consequently offers considerable promise for uncovering the early history

of rice in the Americas.

Research in the archives of other important rice-growing areas of the

African diaspora should be conducted with the objective of identifying mi-

cro-environments planted and the specific soil and water management prin-

ciples that characterized each system. Such an approach facilitates

cross-cultural comparison. A related concern is to situate rice cultivation

within the particular demands of its milling, thus linking the crop's unusual

processing requirements to the transfer from Africa of an indigenous gen-

dered technology. The value of such an approach is to illuminate origins

and diffusion of specific farming complexes as well as the transfer of gen-

dered knowledge systems in food processing and preparation.

Finally, there is the need for a better historical understanding of the trans-

Atlantic networks that facilitated the delivery of African food staples to the

Americas. Eighteenth-century observers of plantation economies attribute cul-

tivation and subsequent diffusion of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) and African oil

palm (Elaeis guineensis) in the Americas to introduction by slave ships (Grime,

1976), thereby drawing attention to the importance of the role of commerce

and scientific societies for the delivery of economically useful plants. However,

less explored are the number of accounts that claim African slaves directly in-

troduced crops like okra (Abelmoschus esculentus), yams (Dioscorea cayenensis),

and cowpeas or black-eyed peas (Jigna unguiculata) to the Americas (Grine,

1976). Like rice, these crops may also have provisioned slave ships bound for

the Americas. And like rice, they became firmly established in slave provision

gardens, which provided the locus for the survival of many African crops among

Black populations of the Americas.18 A historical focus on the food crops of

slave societies as well as the dispersal of African dietary staples across the At-

lantic might illuminate the networks that enabled slaves to obtain seeds of their

favored dietary staples. A shift in the research focus on slave societies from

cash to food crops would undoubtedly improve our understanding of the role

of Africans in establishing their cultivars in the Americas.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author thankfully acknowledges the financial support of the Wen-

ner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research as well as the Interna-

181n 1753, for instance, Sloane (Vol. I, p. 333) records attempts to maintain rice cultivation

in provision gardens by Jamaican slaves on sugar plantations: "This grain is sowed by some

of the Negros in their gardens, and small plantations in Jamaica, and thrives very well in

those that are wet, but because of the difficulty there is in separating the grain from the

husk, 'tis very much neglected, seeing the use of it may be supplied by other grains, more

easily cultivated and made use of with less labour" (quoted in Grim6, 1976, p. 154).

This content downloaded on Wed, 26 Dec 2012 09:24:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

542

Carney

tional Studies and Overseas Programs and Latin American Studies Center

of UCLA for funding this research. She is also grateful for the comments

and insights of Paul Richards, Duncan Vaughan, Leland Ferguson, Deborah

Pearsall, as well as the anonymous reviewers of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

Acevedo, R. (1997). A Escrita do Hist6ria Paraense. NAE/UFPA, Belem, Brasil, pp. 53-91.

Alden, D. (1959). Manoel Luis Vieira: An entrepreneur in Rio de Janeiro during Brazil's

eighteenth century agricultural renaissance. Hispanic American Historical Review 39: 521-

537.

Allston, E R. W (1846). Memoir of the introduction and planting of rice in South Carolina.

Debow's Review I: 320-57.

Baldwin, K. (1957). The Niger Agricultural Project. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Barata, M. [1915] (1973). Formando Hist6rico do Para. Universidade Federal do Para, Belem.

Betts, E. M. (1944). Thomas Jefferson's Garden

Book,

1766-1824. American Philosophical So-

ciety, Philadelphia.

Blake, J. W (1977). West Africa: Quest for God and Gold 1545-1578. Curzon Press, London.

Boxer, C. R. (1965). The Dutch Seabome Empire, 1600-1800. Penguin, London.

Boxer, C. R. (1969). The Portuguese Seabome Empire, 1415-1825. Hutchinson, London.

Brooks, G. (1993). Landlords and Strangers. Ecology, Society and Trade in Westem Africa,

1000-1630. Westview, Boulder.

Burkhill, I. W (1935). A Dictionary of the Economic Plants of the Malay Peninsula. Crown

Agents for the Colonies, London.

Candolle, A. de. (1964). Origin of Cultivated Plants. Hafner, New York (originally published

in 1886).

Carney, J. A. (1986). The Social History of Gambian Rice Production: An Analysis of Food

Security Strategies. PhD dissertation, University of California, Berkeley.

Carney, J. A. (1993). From hands to tutors: African expertise in the South Carolina economy.

Agricultural History 67(3): 1-30.

Carney, J. A. (1996a). Landscapes of technology transfer: Rice cultivation and African con-

tinuities. Technology and Culture 37(1): 5-35.

Carney, J. A. (1996b). Rice milling, gender and slave labour in colonial South Carolina. Past

and Present 153: 108-134.

Carreira, A. (1984). Os Portugueses nos rios de Guin6, 1500-1990. Author, Lisbon.

Chermont, T (1885). Mem6ria sobre a introduccao de arroz branco no estado do gram-para.

Revista Trimensal do Instituto Hist6rico Geogrdphico e Ethnogrdphico do Brasil 48(1): 770-

784.

Chevalier, A. (1932). Les c6r6ales des regions subsahariennes et des oasis. Revue de Botanique

Applique'e et dAgriculture Tropicale 132: 13-134.

Chevalier, A. (1936). L'importance de la Riziculture dans le Domaine Colonial Francais

et l'Ori-

entation a Donner aux Recherches Rizicoles. Laboratoire d'Agronomie Coloniale, Paris,

pp. 27-45.

Chevalier, A. (1937a). Sur le riz Africains du groupe Oryza glaberrima. Revue de Botanique

Applique'e et d'Agriculture Tropicale XVII: 413-418.

Chevalier, A. (1937b). La culture de riz dans la Vall6e du Niger. Revue de Botanique Appliquee

et dAgriculture Tropicale 190: 44-50.

Chevalier, A., and Roehrich, 0. (1914). Sur l'origine botanique des riz cultiv6s. Comptes Ren-

dus de lAcademie de Sciences 159: 560-562.

Cowen, M. (1984). Early years of the colonial development corporation: British state enter-

prise overseas during late colonialism. African Affairs 83(330): 63-75.

Crosby, A. W (1972). The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492.

Greenwood Press, Westport, Cl

This content downloaded on Wed, 26 Dec 2012 09:24:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Rice Cultivation in the Americas 543

Curtin, P (1984). Cross-cultural Trade in World History. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Drayton, J. (1972). A View of South Carolina. University of South Carolina Press, Columbia

(originally published in 1802).

Duncan, T B. (1972). Atlantic Islands: Madeira, the Azores, and the Cape Verdes in Seventeenth

Century Commerce and Navigation. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Ferguson, Leland, April 23, 1998. Professor of Archaeology, University of South Carolina,

Columbia, S.C. [He is an historical archaeologist who works on South Carolina planta-

tions].

Figueiredo, F. (1926). Os Portugueses do seculo XVI e a Historia Natural do Brasil. Revista

de Hist6ria XV: 35-74.

Fonseca, Roberto Jaime. August 1, 1997, Goias, Brazil. Plant breeder and rice specialist at

EMBRAPA, Brazil.

Gaioso, R. J. de Sousa (1970). Compe'ndio Hist6rico-Politico dos Principios da Lavoura do

Maranhdo. Livros do Mundo Inteiro, Rio (originally published in 1853).

Gray, L. (1958). History of Agriculture in the Southem United States to 1860 (2 vols.). Peter

Smith, Gloucester, MA.

Grime, W E. (1976). Botany of the Black Americas. Scholarly Press, St. Clair Shores.

Grist, D. H. (1968) Rice. (4th ed.). Longmans, London.

Hall, G. M. (1992). Africans in Colonial Louisiana. Louisiana State University Press, Baton

Rouge.

Harlan, J. (1995). The Living Fields. University Press, Cambridge.

Hemming, J. (1987). Amazon Frontier MacMillan, London.

Hoehne, F. C. (1937). Botdnica e Agricultura no Brasil no Se'culo XVI. Companhia Editora

Nacional, Sao Paulo.

Hurault, J. (1965). La Vie Materielle des Noirs Refugies Boni et des Indiens Wayana du Haut-

Maroni. Agriculture, Economie et Habitat, ORSTOM, Paris.

Jones, W 0. (1959). Manioc in Africa. Stanford University Press, Stanford.

Klein, M. (1982). The Portuguese slave trade from Angola in the eighteenth century. In Inik-

ori, J. E. (ed.), Forced Migration: The Impact of the Export Slave Trade on African Societies.

African Publishing Company, New York, pp. 221-241.

Kloppenburg, J. (1990). First the Seed. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp. 622-641.

Lawson, J. (1967). A Voyage to Carolina. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.

Lewicki, T (1974). West African Food in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press, Cam-

bridge.

Littlefield, D. C. (1981). Rice and Slaves. Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge.

Lunig, H. A. (1969). The Economic Transformation of Family Rice-Farming in Surinam. Centre

for Agricultural Publishing and Documentation, Wageningen.

Marques, C. (1870). Diciondrio Hist6rico e Geogrdfico da Provincia do Maranhdo. Sao Luis,

Maranhao.

McIntosh, S. K., and McIntosh, R. J. (1993). Cities without citadels: Understanding urban

origins along the middle Niger. In Shaw, T, Sinclair, P., Andah, B., and Okpoko, A.

(eds.), The Archaeology of Africa: Food, Metas and Towns. Routledge, New York.

Miracle, M. (1966). Maize in Tropical Africa. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison.

National Research Council (NRC). (1996). Lost Crops of Africa. National Academy Press,

Washington, D.C.

Nunes Dias, M. (1970). Fomento e Mercantilismno: A Companhia Geral do Grao Para e Ma-

ranhdo (1755-1778). Universidade Federal do Para, Belem.

Oka, Hiko-Ichi (1961). Report of Trip for Investigations of Rice in Latin American Countries.

National Institute of Genetics, Mishima, Japan.

Oliveira, G. C. X. (1993). Padroes de Variacao Fenotipica e Ecologia de Oryzae (Poaceae)

Selvagens da Amazonia. MA thesis, Universidade do Sao Paulo.

Panday, R. M. N. (1959). Agriculture in Surinam 1650-1950. H. J. Paris, Amsterdam.

Pearsall, Deborah, May 4, 1998. Professor of Anthropology, University of Missouri at Colum-

bia. [She is a specialist in phytolith analysis and has pioneered a number of techniques]

This content downloaded on Wed, 26 Dec 2012 09:24:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

544 Carney

Pearsall, D., Pipemo, D., Dinan, E., Umlauf, M., Zhao, Z., and Benter, Jr. R. Distinguishing

rice (Oryza Sativa Poaceae) from wild oryza species through phytouth analysis: Results

of preliminary research. Economic Botany 49(2): 183-196.

Pearsall, D. M. (1989). Paleoethnobotany: A Handbook of Procedures. Academic Press, New

York.

Pelissier, P (1966). Les Paysans du Sene'gal. Imprimerie Fabreque, St. Yrieix.

Peterson, M. D. (1984). Thomas Jefferson Writings: The Library of America, New York.

Piso, G. (1957). Hist6ria Natural e Me'dica da India-Ocidental. Instituto Nacional do Libro,

Rio de Janeiro.

Porteres, R. (1955a). Historique sur les premiers 6chantillons d'Oryza glaberrima St. recueillis

en Afrique. Joumal d'Agriculture Tropicale et de Botanique Appliquee II: 535-705.

Porteres, R. (1955b). Pr6sence ancienne d'une variete cultivee d'Oryza glaberrima St. en Guy-

ane Francaise. Joumal dAgriculture Tropicale et de Botanique Appliquee 11(12): 680.

Port&res, R. (1955c). Un probleme Ethno-botanique: Relations entre le Riz flottant du Rio

Nunez et l'origine medinigerienne des Baga de la Guinee Francaise. Joumal dAgriculture

Tropicale et de Botanique Appliquee 11(10-11): 538-542.

Porteres, R. (1960). Riz subspontan6s et riz sauvages en El Salvador (Am6rique Centrale).

Journal d'Agriculture Tropicale et de Botanique Applique'e 7(9/10): 441-446.

Porteres, R. (1970). Primary cradles of agriculture in the African continent. In Fage, J. D.

and Oliver, R. A. (eds.), Papers in African Prehistory. Cambridge University Press, Cam-

bridge, pp. 43-58.

Porteres, R. (1976). African Cereals: Eleusine, Fonio, Black Fonio, Teff, Brachiaria, Paspalum,

Pennisetum, and African Rice. In Harlan, J., De Wet, J., and Stemler, A. (eds.), Origins

of African Plant Domestication. Mouton, The Hague, pp. 409-452.

Price, R. (1983). First-Time: The Historical Vision of an Afro-American People. Johns Hopkins

Press.

Price, R., and Price, S. (1992). Stedman's Surinam. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

Primeiro, J. (1818). Compendio Hist6rico-Politico dos Principios da Lavoura do Maranhdo.

Paris, Fougeron.

Ribeiro, 0. (1962). Aspectos e Problemas da Expansdo Portugue'sa. Estudos de Ciencias Politicas

e Sociais, Lisbon.

Richards, P (1996). Culture and community values in the selection and maintenance of African

rice. In Brush, S. and Stablinsky, D. (eds.), Indigenous People and Intellectual Property

Rights. Island Press, Washington, D.C., pp. 209-229.

Richardson, D. (1991). The British slave trade to colonial South Carolina. Slavery and Abolition

12: 125-72.

Rochevicz, R. J. (1932). Documents sur le genre Oryza. Revue de Botanique Appliqu&e et d'Ag-

riculture Tropicale 135: 949-61.

Rodney, W (1970). A History of the Upper Guinea Coast 1545 to 1800. Monthly Review Press,

New York.

Rosengarten, D. (1997). Social Origins of the African-American Lowcountry Basket. PhD dis-

sertation, Harvard.

Salley, A. S. (1919). Introduction of Rice into South Carolina. Bulletin of the Historical Com-

mission of South Carolina 6, The State Company, Columbia, South Carolina.

Sano, Y. (1989). The direction of pollen flow between Two co-occurring rice species, Oryza

sativa and 0. glaberrima. Heredity 63: 353-357.

Vaillant, A. (1948). Milieu cultural et classification des varietes de riz des Guyanes frangais

et hollandaise. Revue Intemationale de Botanique Applique'e et d'Agriculture Tropicale xxxiii:

520-529.

Vaughan, Duncan, Sept. 27, 1997, Tskuba, Japan. Formerly rice expert at the International

Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in Los Banos, The Philippines. Currently head, of the

Crop Evolutionary Dynamics Laboratory, National Institute of Agrobiological Resources,

Tskuba, Japan.

Vavilov, N. I. (1951). The Origin, Variation, Immunity and Breeding of Cutivated Plants, Selected

Writings. Ronald Press, New York.

This content downloaded on Wed, 26 Dec 2012 09:24:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Rice Cultivation in the Americas 545

Vergolino, H. A., and Figueiredo, A. N. (1990). A Presenca Africana na Amaz6nia Colonial:

Uma Noticia Hist6oica. Arquivo Puiblico do Para, Bel6m.

Viguier, P (1939). La Riziculture Indigene au Soudan Francais. Larose, Paris.

Viveiros, J. de (1895). Hist6oia do Come'rcio do Maranhdo: 1612-1895 (4 Vols.). Brasil: Ediaao

FAC/SIMILAR, Sao Luis.

Wood, P (1974a). Black Majority. Norton, New York.

Wood, P (1974b). "It was a Negro taught them": A new look at African labor in early South

Carolina, Joumal of Asian and African Studies ix: 160-179.

This content downloaded on Wed, 26 Dec 2012 09:24:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- WHO Concept Paper PDFDocumento13 pagineWHO Concept Paper PDFMillenium AyurvedaNessuna valutazione finora

- Journal of Asiatics 47 8unseDocumento302 pagineJournal of Asiatics 47 8unseMillenium AyurvedaNessuna valutazione finora

- WHO Concept Paper PDFDocumento13 pagineWHO Concept Paper PDFMillenium AyurvedaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ecosystem and Health PDFDocumento64 pagineEcosystem and Health PDFMillenium AyurvedaNessuna valutazione finora

- 3rd Year Syllabus PDFDocumento24 pagine3rd Year Syllabus PDFMillenium Ayurveda100% (1)

- South Organic PDFDocumento376 pagineSouth Organic PDFMillenium Ayurveda100% (1)

- Wardshidoos00sethuoft PDFDocumento422 pagineWardshidoos00sethuoft PDFMillenium AyurvedaNessuna valutazione finora

- 4thBAMS Syllabus PDFDocumento29 pagine4thBAMS Syllabus PDFRajeev B PillaiNessuna valutazione finora

- Journal of Asiatics 26 Beng PDFDocumento731 pagineJournal of Asiatics 26 Beng PDFMillenium AyurvedaNessuna valutazione finora

- Journal of Asiatics 34 Beng PDFDocumento713 pagineJournal of Asiatics 34 Beng PDFMillenium AyurvedaNessuna valutazione finora

- Journal of Asiatics 00 Beng PDFDocumento260 pagineJournal of Asiatics 00 Beng PDFMillenium AyurvedaNessuna valutazione finora

- Journal of Asiatics 19 Beng PDFDocumento625 pagineJournal of Asiatics 19 Beng PDFMillenium AyurvedaNessuna valutazione finora

- EinsteinDocumento4 pagineEinsteinanc2061Nessuna valutazione finora

- Snakes of CeylonDocumento108 pagineSnakes of Ceylontobiasaxo5653Nessuna valutazione finora

- Historical Journl I PDFDocumento62 pagineHistorical Journl I PDFMillenium AyurvedaNessuna valutazione finora

- Garbhaguhya Tantra PDFDocumento47 pagineGarbhaguhya Tantra PDFMillenium Ayurveda100% (1)

- Journal RAS PDFDocumento543 pagineJournal RAS PDFMillenium AyurvedaNessuna valutazione finora

- Homeopathy & Ayurvedic Medicine: A Study On The Plants Used As ChopachiniDocumento4 pagineHomeopathy & Ayurvedic Medicine: A Study On The Plants Used As ChopachiniMillenium AyurvedaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sinhalese Rituals PDFDocumento567 pagineSinhalese Rituals PDFMillenium AyurvedaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ancient Ceylon PDFDocumento320 pagineAncient Ceylon PDFMillenium Ayurveda100% (1)

- Citadel of Anuradhapura PDFDocumento119 pagineCitadel of Anuradhapura PDFMillenium AyurvedaNessuna valutazione finora

- Voynich PDFDocumento4 pagineVoynich PDFMillenium AyurvedaNessuna valutazione finora

- Hamilton 1831 History of Medicine PDFDocumento751 pagineHamilton 1831 History of Medicine PDFMillenium AyurvedaNessuna valutazione finora

- Newar Buddhism PDFDocumento12 pagineNewar Buddhism PDFMillenium AyurvedaNessuna valutazione finora

- Amoghapasa PDFDocumento9 pagineAmoghapasa PDFMillenium AyurvedaNessuna valutazione finora

- Deities Buddhist PDFDocumento22 pagineDeities Buddhist PDFMillenium AyurvedaNessuna valutazione finora

- Nathan Sivin - On The Word Taoist As A Source of PerplexityDocumento29 pagineNathan Sivin - On The Word Taoist As A Source of Perplexity\Nessuna valutazione finora

- GayadasaDocumento5 pagineGayadasaMillenium AyurvedaNessuna valutazione finora

- 1990-A Hirakawa-A History of Indian Buddhism-From Śākyamuni To Early Mahāyāna PDFDocumento424 pagine1990-A Hirakawa-A History of Indian Buddhism-From Śākyamuni To Early Mahāyāna PDFFengfeifei2018Nessuna valutazione finora

- Nathan Sivin - On The Word Taoist As A Source of PerplexityDocumento29 pagineNathan Sivin - On The Word Taoist As A Source of Perplexity\Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Scientia MARDI - Vol. 007 - March 2016Documento12 pagineScientia MARDI - Vol. 007 - March 2016MARDI Scribd100% (1)

- Year I: Department of Plant Science Course Breaks Down For B. SC ProgramDocumento2 pagineYear I: Department of Plant Science Course Breaks Down For B. SC ProgramseiyfuNessuna valutazione finora

- For HYV SeedsDocumento5 pagineFor HYV Seedslapis37120Nessuna valutazione finora

- Guidelines For The Value Chain Fund: AgrobigDocumento42 pagineGuidelines For The Value Chain Fund: Agrobigabel_kayelNessuna valutazione finora

- A Project Report On Consumer Awareness About Nandini Milk and Milk ProductsDocumento73 pagineA Project Report On Consumer Awareness About Nandini Milk and Milk ProductsBabasab Patil (Karrisatte)100% (2)

- Meat-Consuming Nation: Consumers-Say-ExpertsDocumento2 pagineMeat-Consuming Nation: Consumers-Say-ExpertsMirlorNessuna valutazione finora

- Time Series AnalysisDocumento23 pagineTime Series AnalysisSandeep BadoniNessuna valutazione finora

- Doroteo S. Mendoza Sr. Memorial National High School: Division of Oriental MindoroDocumento18 pagineDoroteo S. Mendoza Sr. Memorial National High School: Division of Oriental MindoroJhay-Ar Valdrez CastilloNessuna valutazione finora

- The Minnesota Messenia ExpeditionDocumento417 pagineThe Minnesota Messenia ExpeditionYannis Ladas100% (4)

- Wildlife Fact File - Mammals - Pgs. 71-80Documento20 pagineWildlife Fact File - Mammals - Pgs. 71-80ClearMind84100% (5)

- Soil Analysis and Agricultural Survey: Jagtap & K. P. Patel 2014)Documento7 pagineSoil Analysis and Agricultural Survey: Jagtap & K. P. Patel 2014)Sarvesh RautNessuna valutazione finora

- Millet Recipes: - A Healthy ChoiceDocumento66 pagineMillet Recipes: - A Healthy ChoiceRudra BluestacksNessuna valutazione finora

- A Business PropDocumento18 pagineA Business PropJoseph IsraelNessuna valutazione finora

- Monsanto's Dark History 1901-2013Documento24 pagineMonsanto's Dark History 1901-2013Leo PeccatuNessuna valutazione finora

- What'S Inside: Julie PondDocumento7 pagineWhat'S Inside: Julie PondnwberryfoundationNessuna valutazione finora

- Rahul Manyagol - Final ReportDocumento21 pagineRahul Manyagol - Final ReportEswar SudharsanNessuna valutazione finora

- Draft Horse Primer Guide To Care Use of Work Horses and Mules 1977Documento396 pagineDraft Horse Primer Guide To Care Use of Work Horses and Mules 1977Radu IliescuNessuna valutazione finora

- Wcca India AbstractsDocumento493 pagineWcca India Abstractsbch_bhaskar100% (2)

- 1-Nonlinear Regression Models in Agriculture PDFDocumento9 pagine1-Nonlinear Regression Models in Agriculture PDFinternetidentityscriNessuna valutazione finora

- MA - Resource Use in The Lubombo TFCA - RJ KloppersDocumento243 pagineMA - Resource Use in The Lubombo TFCA - RJ Kloppersapi-3750042Nessuna valutazione finora

- Master SampleDocumento26 pagineMaster SampleHồNessuna valutazione finora

- What's New in Biological Control of Weeds? Issue 52 Vol 10Documento8 pagineWhat's New in Biological Control of Weeds? Issue 52 Vol 10lellobotNessuna valutazione finora

- Soil Laboratory Experiment Report2Documento6 pagineSoil Laboratory Experiment Report2AlejandroGonzagaNessuna valutazione finora

- Flash Flood Variety Article IJPGR 2010Documento3 pagineFlash Flood Variety Article IJPGR 2010sabavaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Ulnaby Hall - High ConiscliffeDocumento47 pagineUlnaby Hall - High ConiscliffeWessex ArchaeologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Rice Milling: Poonam DhankharDocumento9 pagineRice Milling: Poonam DhankharWeare1_busyNessuna valutazione finora

- Directorate of AgricultureDocumento187 pagineDirectorate of AgriculturematriadvertNessuna valutazione finora

- Coffee Final Project Proposal by BobDocumento23 pagineCoffee Final Project Proposal by BobWesley オングNessuna valutazione finora

- Prof. Dr. Ashraf-CV October-2019Documento107 pagineProf. Dr. Ashraf-CV October-2019Muhammad Waqas MustafaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2.history of ExtensionDocumento22 pagine2.history of ExtensionNico Rey Yamas RANessuna valutazione finora