Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Compose For Harp

Caricato da

tychethDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Compose For Harp

Caricato da

tychethCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Introduction to composing music for the Concert Harp

Occasionally when I am out performing on my harp someone will ask me about how to compose music

for the harp (Im going to run with harp instead of concert harp from now on). My standard short answer

is that it is similar to writing for the piano. Well, compared to other instruments written harp music is

most similar to written piano music, and all musicians are familiar with how a piano works. More recently

I have been asked to play some piano music on the harp to accompany a choir. This has started me

thinking about the what is the same about writing for the harp and the piano, and what is different.

I hope that the following information inspires you to write for the harp. I would really appreciate any

feedback that you may have. Send me an email at kristina@animatedcreations.net

Thank you,

Kristina Sara Johnson

Harpists use only four ngers to play

Well, we just do. We ignore the 5th finger. We can reach over a lot more notes than a pianist can,

though. A stretch of a 10th is easy to do on the harp. Compositions for the harp frequently contain

chords with the notes spread over a 10th or sometimes more.

Some starting notes about notation

The notation for both harp and piano is superficially similar. We both read treble and bass clef, spread

across two staves where the right hand mostly plays the top line and the left hand mostly plays the

bottom line. However, it would be fair to say that which hand plays where is treated as a much more

elastic concept by harpists as much of the instrument is equally accessible by both hands. The left hand

can play in any register of the harp, although harpists dont really like having the left hand up in the top

two octaves if they can avoid it. The right hand is a bit more restricted by the harp resting on our right

shoulder and our right arm reaching around the harp to the strings. Unless the harpist has really long

arms, it will be troublesome for them to reach beyond the first few metal strings (G to E, 1.5 octaves

below middle C).

Its worth pointing out here that harpists do not find guitar chord diagrams very useful. Yes, people have

given this stuff to me, because I suppose both instruments have strings and in their minds that is similar

enough. I can take the guitar music away and go and write something that works on the harp, but that

will cost you extra.

The harp, like the piano, is a non-transposing instrument. What is written is how it sounds. The concert

harp is tuned to concert pitch.

The range of a piano and a harp are very similar. The lowest string on a concert harp is C three octaves

below middle C. The lowest note on the piano is the A below this C. The highest string on a concert harp

is G four octaves above middle C. The highest note on the piano is the C above this G. Within this

range, the notes available to the harp and the piano are the same. The difference is that the harp is in

some ways more restricted than the piano in what combinations are allowable. The upside of this is that

the pedals on a concert harp allow harpists some very interesting options not so easily available to

pianists.

The Range of the Harp:

Introduction to composing music for the Concert Harp - Kristina Sara Johnson

The basics of pedals

The harp has 47 strings and 7 pedals. Each pedal has 3 positions - flat, natural and sharp. The lowest C

and D on the harp are not affected by the pedals, and are retuned as required. The natural scale of the

harp, with all the pedals in the top position, is C flat major. With all the pedals in the middle position you

have C major, and logically, with all the pedals in the low position you have C sharp major. When a

pedal is depressed on the harp, this activates discs at the top of the string that increase the string

tension. There is one disc engaged for naturals, and a second disc additionally engaged for sharps.

These discs, and to a lesser extent the bits that connect the pedals to the discs are prone to getting out

of alignment (for lots of different reasons). A harp needs to be regulated to keep these problems in

check. What does this mean for a composer? Harpists prefer flats. If you ask a harpist what their

favourite key is, it will be one with a lot of flats. We can guarantee that flats are always in tune. The

sharper things get, the more likely it is that some discs will cause strings to sound slightly out of tune.

The layout of pedals on the harp influences what we are able to play. On the left side of the harp, from

outside to inside, are the pedals D, C and B. On the right side of the harp, from outside to inside, are the

pedals A, G, F and E. We can also reach the B pedal with the right foot, and the E pedal with the left

foot, but this is awkward. So, this means we can change two pedals, one for each foot, at a time. So

while the pianist thinks about the loud pedal and the damp pedal, the harpist has to keep track of 7

pedals and which are flat, natural or sharp. I tend think of this as the 3rd line on the music after treble

and bass.

Harpists like to keep track of what pedals they should have at any point by scrawling pedal changes and

little pedal diagrams on their music. What combinations of pedal changes and how the diagrams are

written will vary from harpist to harpist, but you can be sure that they will all have equally strong

opinions about how they go about this. Occasionally a composer will print a pedal diagram at the start of

a piece of music.

Pedal diagram (usually just shown as lines without the labels):

Introduction to composing music for the Concert Harp - Kristina Sara Johnson

Enharmonic equivalents

Harpists do a lot of thinking in enharmonic equivalents to optimise their pedal choices. They then write

in all the pedals and draw circles around the enharmonically changed notes to remind themselves to play

a different string. When this gets too extreme, the harpist will get upset and rewrite the music to their

own satisfaction and stick the manuscript over the top of all the scribbling to save their sanity. The

manuscript and sticky tape approach usually only applies when we are trying to play something written

for the piano on the harp.

Example: Pice in C, Op. 39, Chausson

First, ignore that cello line running along the top. The lower part is written for the piano. I have heard a

recording of this played on the harp by Xavier de Maistre and loved it so much I decided to get the music

for myself. Hearing a recording is often where trouble starts.

There are several issues with this example that I am using enharmonic equivalents to resolve:

1. A harpist cant change all those flats into sharps fast enough to read the music as written in the first

two bars. Not that we would necessarily want to, because harpists prefer flats. Still, doing it this way

remains a mind bender.

2. In the last two bars there is the use of the enharmonic equivalent of G sharp and A flat. This is partly

to get around playing repeated notes, which resonate better on alternated strings at the same pitch.

This is also because changing the G pedal more often would cause the string to buzz. Lastly, this is

the only way we can get G natural in the bass and G sharp (A flat here) in the treble at the same time.

On the upside, at least the thing is not too fast to play, because with all these pedals going on it would

never work otherwise. I havent even played through this yet to decide which fingers I want to use, or

even which hands. Even without all that written in, this mess of pedal changes, pedal diagrams and

enharmonic reminder circles is a bit scary looking. I may even decide later to go with different pedal

combinations that better suit a fingering that I like. If that is even possible. It could be time to get the

spare manuscript and the sticky tape....

Introduction to composing music for the Concert Harp - Kristina Sara Johnson

As a result of the very enharmonic nature of the harp, music written for the harp tends to disregard some

traditional rules of composition. Its infrequent that there will ever be a written double-sharp or double-

flat. In its place the actual note as it sounds will appear. When composing for the harp, be sure to

explore all of the enharmonic options available to you. It is one of the things that makes music for the

harp so wonderful and unique.

Glissandi and Slides

Lots of fun with all those pedals to play with. Shown below are:

1. A glissando from C to G

2. A slide between two notes

Harmonics

It is possible to play harmonics on most strings of the harp. Right up the top there isnt really enough

space to manage it. The most common harmonic is the one sounding an octave higher than the string

played, but other harmonics are also possible. Harmonics are usually played on a single string. The

harmonic technique for the right hand means that the right hand can only play one harmonic at a time.

The left hand technique allows for one, two or three notes to sound harmonically at once, but these

strings will need to be close together for it to work. Sometimes harmonics are written on the note that

they sound, with the actual harmonic played an octave lower. Sometimes they are written where they

should be played. It is important to note your preference somewhere on the music. I personally prefer

the harmonic to be written where it sounds.

Harmonics are very commonly used on compositions for the harp because of their lovely ringing bell

sound. It is quite a different sound quality to a string played naturally.

Introduction to composing music for the Concert Harp - Kristina Sara Johnson

Fingerings

Harpists like playing things that fit under their hands easily. Arpeggios and chords where we can grab

four strings at a time make us happy.

Example: Le Moulin, from the soundtrack to the film Amlie, Yann Tiersen.

This is one of my favourite film soundtracks of all time. As Ive said before, the trouble usually starts

when I hear a recording of something irresistible. This figure is straightforward on the piano. It doesnt

fit easily under a harpists four fingers at all. My personal work around is the fingering shown below the

bass line. Less experienced harpists would probably not consider this option, and would probably not feel

comfortable playing it. Thus, it is an example of writing that generally makes life more difficult for

harpists. Four fingers = good. Five fingers = bad.

Printing suggestions for ngerings on the music

This is probably something a non-harpist composer shouldnt attempt to do. If you decide to consult with

a harpist in this matter, different harpists will recommend different fingers based on their own technique.

What works - Harp vs. Piano

Chromatic scales

The piano is the master of chromatic scales. In comparison, the harp is very much a diatonic instrument.

Fast chromatic scales, like those favoured by Chopin, will not work on the harp.

Example: Polonaise in A flat major, Op. 53, Chopin

Introduction to composing music for the Concert Harp - Kristina Sara Johnson

Fast repeated chords on the same notes

The piano wins hands down in this category too. Once the keys are played on the piano, the sound rings

on, even if you repeat those same notes right away. On a harp, if the string stops vibrating, then that

note is lost. If you keep quickly repeating a chord on a harp, the sound is lost.

There is almost an exception to this rule. If enharmonic equivalents or different fingers (or both) can be

used for repeated notes, it will help. Replacing the same fingers on the same strings is what harpists

really want to avoid.

Example: Battle Hymn of the Republic, W. Steffe. Arranged for piano and choir by P. Wilhousky.

This sort of writing really does not work on the harp. The tempo is that of a march.

Example: This Little Babe from A Ceremony of Carols, Op. 28, Britten.

This example is faster than the one above, but it works well on the harp. It too has fast repeated notes.

So, what is the difference here? The harpist can alternate the chords in the right (tails up) and left (tails

down) hands. Very precise replacing of the fingers on the strings is needed for this to be effective.

Introduction to composing music for the Concert Harp - Kristina Sara Johnson

Example: Cantique de Jean Racine, Op. 11, Faur.

This example is taken from the piano accompaniment. I was asked to play it on the harp. This passage

has a lot of repeated notes. The notes in the middle line with the arc drawn over them are the ones Im

taking with the left hand. I chose the fingerings marked below to maximise the resonance of the passage

and gain clean finger replacement. Avoiding using the same finger again can help with this strategy. At

a slow Andante pace of crotchet M.M. 80, this makes the Cantique a very big homework task indeed.

Avoiding Buzzing

All those vibrating strings can be a hazard. You cannot half touch, brush past, or change a pedal disc on

a piano key. All these things cause whatever it is lightly touching the string to create a buzzing noise.

Some harpists consider this to be an unavoidable part of playing the harp and accept things as they are.

Those of us who subscribe to the Salzedo technique like to avoid buzzes altogether.

Example: Battle Hymn of the Republic, W. Steffe. Arranged for piano and choir by P. Wilhousky.

This sort of writing really does not work on the harp. The tempo is that of a march. The top notes in

this will stop vibrating quite quickly. The bottom line on mostly metal strings will ring on for a long time.

The metal strings will still be ringing when you go to play them again. It is very difficult for a harpist not

to make a lot of buzzing noises on the strings when placing the fingers in a sequence like this one.

Additionally, the fast replacing on strings just played kills the resonance and you lose the effect that this

would have on the piano. A good work around for the harpist would be to just choose two lines of the

four and play these as four finger scales. It would sound a lot thinner, though.

Introduction to composing music for the Concert Harp - Kristina Sara Johnson

Example: The Young Persons Guide to the Orchestra, Op. 34, Britten

The tempo of this harp solo is around crotchet M.M. 72. This makes this little figure one nasty pest on

the harp. It is very easy to make buzzing noises by brushing past already vibrating strings when

grabbing the next chord on the way down the sequence. Looks innocent, but requires a lot of practice to

get it to work.

Harpists think this stu" is easy

I think that the harp trumps the piano in the following categories.

Glissandi

Mentioned a few pages ago. Actually, anyone can sit down at a harp and run their fingers along the

strings to create a glissando, but it takes a proper harpist to make it sound really cool.

Arpeggi

So much harp music is centred around the arpeggio, and with good reason because they sound so

beautiful on the harp. A grand example is the cadenza from Tchaikovskys Waltz of the Flowers from the

Nutcracker Suite. This cadenza is based on inversions of a dominant 7th chord, and very little else.

Chords and their inversions are drilled into harpists from their very first lessons.

Example: Impromptu for Harp, Op. 86, Faur.

Introduction to composing music for the Concert Harp - Kristina Sara Johnson

Big Chords

Little chords are OK too, of course.

Example: Impromptu for Harp, Op. 86, Faur.

Tied notes and sustained sound

The length of time a note can be held for on the harp is dependent on which register it is played in. Once

the harp string is played, there is a certain amount of time it will vibrate for. At the top of the harp, the

thin nylon strings sound for only a very short time. At the bottom of the harp, the metal bass strings

ring on and on. Everything else is somewhere in between these two extremes. Notes tied across bars

are only really meaningful if used in the bass register. Bass strings often need to be damped or muffled

to stop them from sounding much longer than required.

Rests and mu#ing

On the piano, a rest happens when the pianist isnt playing any keys. On a harp, a rest happens when

the harpist places their hands on the strings to stop them vibrating. This is referred to as damping or

muffling the strings. If this is not done, whatever was last played will keep resonating until the sound

fades away. It is important for the composer to be specific about how they want their rests to happen

when writing for the harp.

In the diagram below, there are four examples of different types of string muffling on the harp. There

are actually more than these, but these are the ones most commonly seen.

1. The muffle symbol

2. Muffle one, two, three or four distinct notes with separate fingers

3. Muffle a group of strings between the two notes marked, using the palm of the hand

4. Muffle all of the bass strings

Staccato and Legato

The natural sound of the harp is long sustained notes, with layers of sustained sound depending on the

duration of the vibration of the previously played strings. The only way a harpist can achieve a true

staccato, is to damp the strings played immediately after playing them by replacing all of the fingers.

There are things the harpist can do to give a sense of a more staccato note as opposed to one played

legato, and this intention in the sound can only be achieved by particular playing, placing and phrasing.

Regardless of the specific technique the harpist uses, they should be able to go on about their own

personal philosophies on this topic for several pages.

Introduction to composing music for the Concert Harp - Kristina Sara Johnson

Listening homework

A rough guide to some of my favourite recordings. Between them, they show off the huge range of

fantastic works that have been written or adapted for the harp.

Alice Giles - Harp Concertos: Ginastera/Glire/Jolivet with the Adelaide Symphony

Alice Giles - Carlos Salzedo: Works for Solo Harp

Judy Loman - 20th Century Masterworks for Harp

Judy Loman - Harp Showpieces

Judy Loman - The Romantic Harp

Judy Loman - Musique De Chambre Franaise

Judy Loman - The Baroque Harp - Bach and Scarlatti

Seven Harp Ensemble - Bolmimerie

Xavier De Maistre - French Concertos for Harp

Xavier De Maistre - French Trios

Reading homework

Excellent reference on harp technique and effects. Yes, I am biased because I am Salzedo technique

player myself. I can only recommend what I know.

Method for the Harp, Lawrence / Salzedo (Schirmer)

Modern Study of the Harp, Carlos Salzedo (Schirmer)

Introduction to composing music for the Concert Harp - Kristina Sara Johnson

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Harp SpectrumDocumento12 pagineHarp SpectrumokksekkNessuna valutazione finora

- Writing for the Harp: Tips for ComposersDocumento3 pagineWriting for the Harp: Tips for ComposersAnne ZeuwtsNessuna valutazione finora

- composeForHarp PDFDocumento10 paginecomposeForHarp PDFtycheth100% (2)

- Writing For The HarpDocumento8 pagineWriting For The HarpSteve Tomato100% (1)

- Harp Pedal Grade 3Documento10 pagineHarp Pedal Grade 3suscripcion71Nessuna valutazione finora

- HARP - Salzedo - L'Etude Modern Del HarpDocumento84 pagineHARP - Salzedo - L'Etude Modern Del HarpOsvaldo SuarezNessuna valutazione finora

- Fire DancesDocumento8 pagineFire DancesMat MartinNessuna valutazione finora

- Harp Syllabus - Grades 1-8Documento15 pagineHarp Syllabus - Grades 1-8Alex DurstonNessuna valutazione finora

- The Pedal Harp and Its AcousticsDocumento9 pagineThe Pedal Harp and Its AcousticsNatalie Lebedeva100% (2)

- Harp - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocumento20 pagineHarp - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediajazzclubNessuna valutazione finora

- Transcribing For HarpDocumento123 pagineTranscribing For HarpEduardo RodríguesNessuna valutazione finora

- Studies For HarpDocumento38 pagineStudies For HarpRodrigo Eduardo Gallegos MillánNessuna valutazione finora

- Harp Syllabus 2009Documento82 pagineHarp Syllabus 2009semiring100% (3)

- Harp in JazzDocumento160 pagineHarp in JazzSergio Rizzo100% (2)

- Harp Solo PDFDocumento9 pagineHarp Solo PDFIvy Keung100% (2)

- Wurlitzer HarpDocumento15 pagineWurlitzer HarpMichael LundNessuna valutazione finora

- Notating Music For The Harp in Sibelius 06 20 2019Documento45 pagineNotating Music For The Harp in Sibelius 06 20 2019pedritolopezNessuna valutazione finora

- Music Notation BibliographyDocumento5 pagineMusic Notation BibliographyDamien Rhys JonesNessuna valutazione finora

- Building A Balalaika William PrinceDocumento22 pagineBuilding A Balalaika William PrinceArnab BhattacharyaNessuna valutazione finora

- An CruitireDocumento22 pagineAn CruitireThe Journal of Music100% (1)

- The Charming Rise of the Modern HarpDocumento5 pagineThe Charming Rise of the Modern HarpSaharAbdelRahmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Violin 0712Documento2 pagineViolin 0712Chen Inn TanNessuna valutazione finora

- CinePerc Manual English PDFDocumento153 pagineCinePerc Manual English PDFCesar DangondNessuna valutazione finora

- Harp High Level TheoryDocumento46 pagineHarp High Level TheoryColin PonNessuna valutazione finora

- Harp Exercises For Agility and Speed - Deborah Friou - September 1989 - Woods Music & Books, Incorporated - 9780936661049 - Anna's ArchiveDocumento100 pagineHarp Exercises For Agility and Speed - Deborah Friou - September 1989 - Woods Music & Books, Incorporated - 9780936661049 - Anna's ArchiveArmando VicuñaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ian Shanahan - Recorder Unlimited (MMus (Hons) - PHD Prelim.) (Scanned OCR)Documento336 pagineIan Shanahan - Recorder Unlimited (MMus (Hons) - PHD Prelim.) (Scanned OCR)Ian Shanahan100% (3)

- Cinematic Studio Brass User ManualDocumento8 pagineCinematic Studio Brass User ManualJorge Camarero100% (1)

- HarpDocumento9 pagineHarpSergio Miguel MiguelNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Play The Celtic HarpDocumento29 pagineHow To Play The Celtic HarpDougCrouse100% (5)

- Hua Yanjun (1893-1950) and Liu Tianhua (1895-1932)Documento11 pagineHua Yanjun (1893-1950) and Liu Tianhua (1895-1932)Mandy ChengNessuna valutazione finora

- Effective Harp Pedagogy TechniquesDocumento263 pagineEffective Harp Pedagogy TechniquesYonca Atar80% (5)

- Concerto For Harp and OrchestraDocumento2 pagineConcerto For Harp and OrchestraSebastián Carrasco MendozaNessuna valutazione finora

- History of The HarpDocumento4 pagineHistory of The Harpskmathew2100% (1)

- Music in Indie Video Games - A Composer - S Perspective On Musical Approaches and Practices PDFDocumento167 pagineMusic in Indie Video Games - A Composer - S Perspective On Musical Approaches and Practices PDFlebannem100% (2)

- ShengDocumento13 pagineShengJia-Wen J-wNessuna valutazione finora

- The Rudiments of Highlife MusicDocumento18 pagineThe Rudiments of Highlife MusicRobert RobinsonNessuna valutazione finora

- Asian Plucked InstrumentsDocumento29 pagineAsian Plucked Instrumentsgukumatz100% (1)

- Black Angels Performance NotesDocumento5 pagineBlack Angels Performance NotesJuan Sebastian RizoNessuna valutazione finora

- Rhythm BingoDocumento18 pagineRhythm BingoRachel JadeNessuna valutazione finora

- Strange Loops: Looking Into MusicDocumento13 pagineStrange Loops: Looking Into Musicpineconepalace100% (1)

- Harp Pedal Syllabus Grades 1-8 From 2019 PDFDocumento36 pagineHarp Pedal Syllabus Grades 1-8 From 2019 PDFmeg100% (1)

- Kaija Saariaho, Maa, Harp PartDocumento22 pagineKaija Saariaho, Maa, Harp PartLucia BovaNessuna valutazione finora

- Harmonic Series (Music)Documento5 pagineHarmonic Series (Music)Miguel100% (1)

- Harp Music 02 LondDocumento184 pagineHarp Music 02 Londwongyinlai50% (2)

- Le Trascrizioni Di Grandjany PDFDocumento415 pagineLe Trascrizioni Di Grandjany PDFAnonymous jNzvpKNessuna valutazione finora

- Lyon and Healy Folk Harp String ChartDocumento1 paginaLyon and Healy Folk Harp String ChartHeidi DiederichNessuna valutazione finora

- National 4 New Literacy Workbook 2013Documento28 pagineNational 4 New Literacy Workbook 2013api-246109149Nessuna valutazione finora

- AP Music Theory SyllabusDocumento10 pagineAP Music Theory SyllabusBrianNessuna valutazione finora

- 'S Tips On Backing Irish Music: Henrik NorbeckDocumento3 pagine'S Tips On Backing Irish Music: Henrik NorbeckharaldjulyNessuna valutazione finora

- Facet Analysis of Video Game GenresDocumento15 pagineFacet Analysis of Video Game GenresDubravka MaricNessuna valutazione finora

- Part Writing ErrorsDocumento1 paginaPart Writing Errorsddm8053Nessuna valutazione finora

- Swan Lake - Transcribed For Celtic Harp PDFDocumento2 pagineSwan Lake - Transcribed For Celtic Harp PDFMichael Turner100% (1)

- Zheng by Samuel Wong ShengmiaoDocumento15 pagineZheng by Samuel Wong ShengmiaoSiraseth Pantura-umpornNessuna valutazione finora

- Resource For "Sleep" by Eric Whitacre - Stephen LangeDocumento4 pagineResource For "Sleep" by Eric Whitacre - Stephen LangeP ZNessuna valutazione finora

- Instruments of The OrchestraDocumento5 pagineInstruments of The OrchestraalexnekitaNessuna valutazione finora

- Modular ScalesDocumento35 pagineModular ScalesS.S.F.T.S.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sammartini Symphony in F Major - Brief Analysis PDFDocumento1 paginaSammartini Symphony in F Major - Brief Analysis PDFfadikallab2433100% (1)

- The Basics of Horn ArrangingDocumento9 pagineThe Basics of Horn ArrangingWendy Phua100% (3)

- Rioting With Stravinsky. A Particular Analysis of "The Rite of The Spring"Documento51 pagineRioting With Stravinsky. A Particular Analysis of "The Rite of The Spring"tycheth100% (1)

- PHD - A Theory of Harmony and Voice Leading in The Music of Stravinsky (1981 Straus)Documento199 paginePHD - A Theory of Harmony and Voice Leading in The Music of Stravinsky (1981 Straus)Gea Castiglione50% (2)

- Origin Platos MusicDocumento7 pagineOrigin Platos MusictychethNessuna valutazione finora

- Lutowslawski's "Livre Pour Orchestre" and The Enigma of Musical NarrativityDocumento42 pagineLutowslawski's "Livre Pour Orchestre" and The Enigma of Musical NarrativitytychethNessuna valutazione finora

- British Forum For EthnomusicologyDocumento15 pagineBritish Forum For EthnomusicologytychethNessuna valutazione finora

- Screens Fade To Black Contemporary African American CinemaDocumento230 pagineScreens Fade To Black Contemporary African American CinemajornalismorsNessuna valutazione finora

- + C DWH 3IG L@ IG@L DI 2IH@? ILDBDH F 0gjiln@ @H, OlimDocumento1 pagina+ C DWH 3IG L@ IG@L DI 2IH@? ILDBDH F 0gjiln@ @H, OlimtychethNessuna valutazione finora

- Lutoslawski On The Genuineness and Order of The Platonic DialoguesDocumento4 pagineLutoslawski On The Genuineness and Order of The Platonic DialoguestychethNessuna valutazione finora

- W. Lutoslawski - The Ethical Consequences of The Doctrine of ImmortalityDocumento17 pagineW. Lutoslawski - The Ethical Consequences of The Doctrine of ImmortalitytychethNessuna valutazione finora

- AA - VV., Matrix and PhilosophyDocumento259 pagineAA - VV., Matrix and PhilosophyFrancesco Passariello100% (1)

- Sonata: D S K.176 L.163 Cantabile AndanteDocumento5 pagineSonata: D S K.176 L.163 Cantabile AndantetychethNessuna valutazione finora

- James Monaco-How To Read A FilmDocumento667 pagineJames Monaco-How To Read A FilmAntri.An100% (9)

- OFYRPO43-05 Product Sheet - OFYR Cookbook EN v2Documento1 paginaOFYRPO43-05 Product Sheet - OFYR Cookbook EN v2tychethNessuna valutazione finora

- Hollywood Catwalk Jeffers MacdonaldDocumento257 pagineHollywood Catwalk Jeffers MacdonaldMarcos MatoNessuna valutazione finora

- Origin Platos MusicDocumento7 pagineOrigin Platos MusictychethNessuna valutazione finora

- Find HarmonicsDocumento4 pagineFind HarmonicstychethNessuna valutazione finora

- Find HarmonicsDocumento4 pagineFind HarmonicstychethNessuna valutazione finora

- A. Vivaldi - Winter, 1st ViolinDocumento5 pagineA. Vivaldi - Winter, 1st ViolinMichaelTranNessuna valutazione finora

- Inverno (Concerto No. 4 Violoncelo - Cello PDFDocumento4 pagineInverno (Concerto No. 4 Violoncelo - Cello PDFRony MouraNessuna valutazione finora

- The Mission Gabriels Oboe Partitura Orchestrale PDFDocumento3 pagineThe Mission Gabriels Oboe Partitura Orchestrale PDFBeatriz PintoNessuna valutazione finora

- Adagio in G, D 178 PDFDocumento4 pagineAdagio in G, D 178 PDFtychethNessuna valutazione finora

- DSCH Dimitri Chostakovitch Shostakovich Schostakowich Quartet Quatuor N°2 Sheet Partition Violin PDFDocumento28 pagineDSCH Dimitri Chostakovitch Shostakovich Schostakowich Quartet Quatuor N°2 Sheet Partition Violin PDFtychethNessuna valutazione finora

- The Conwoy - Horace o Prell PDFDocumento26 pagineThe Conwoy - Horace o Prell PDFtychethNessuna valutazione finora

- Marcha. - Troopers Tribunarl March - Henry Fillmore PDFDocumento24 pagineMarcha. - Troopers Tribunarl March - Henry Fillmore PDFCarlos Alb CarreteroNessuna valutazione finora

- Adagio in C, D 349 PDFDocumento2 pagineAdagio in C, D 349 PDFtychethNessuna valutazione finora

- Holst - 4 Vieux Chants Anglais Pour Choeur Et OrgueDocumento14 pagineHolst - 4 Vieux Chants Anglais Pour Choeur Et OrguefabiuzzoNessuna valutazione finora

- Find HarmonicsDocumento4 pagineFind HarmonicstychethNessuna valutazione finora

- Legion User ManualDocumento44 pagineLegion User ManualVedant ChindheNessuna valutazione finora

- 8 Popular Online Food Home Delivery Services in BangladeshDocumento7 pagine8 Popular Online Food Home Delivery Services in BangladeshHAFIZA AKTHER KHANAMNessuna valutazione finora

- Microsoft OfficeDocumento113 pagineMicrosoft Officeaditya00012Nessuna valutazione finora

- Install Guide Spunlite Poles 2015Documento6 pagineInstall Guide Spunlite Poles 2015Balaji PalaniNessuna valutazione finora

- BMC Spicylicious Pancake BaruDocumento1 paginaBMC Spicylicious Pancake BaruMuhamad DanialNessuna valutazione finora

- Teza LB Engleza - Intensiv A VII ADocumento2 pagineTeza LB Engleza - Intensiv A VII ADoina CristeaNessuna valutazione finora

- Nishu 3Documento2 pagineNishu 3Dibya DillipNessuna valutazione finora

- Grade 9 Unit 2 - StudentDocumento84 pagineGrade 9 Unit 2 - Studentapi-296701419100% (1)

- Being Nice MonologueDocumento3 pagineBeing Nice Monologuechante gladNessuna valutazione finora

- Practice ProblemsDocumento4 paginePractice ProblemsPalash dasNessuna valutazione finora

- Stretch cheatsheet for shoulder, core, hip and yoga routinesDocumento2 pagineStretch cheatsheet for shoulder, core, hip and yoga routinesvoodoojujuNessuna valutazione finora

- 7880R2x1-ASI-CS 1v5Documento54 pagine7880R2x1-ASI-CS 1v5Silvio JesusNessuna valutazione finora

- Trip Oil SystemDocumento6 pagineTrip Oil Systemsmart_eng2009100% (3)

- Invisible Sun FREE PREVIEW PDFDocumento55 pagineInvisible Sun FREE PREVIEW PDFJosé AntonioNessuna valutazione finora

- Schoenberg Noche TransfiguradaDocumento167 pagineSchoenberg Noche TransfiguradaAdina IzarraNessuna valutazione finora

- Sarees Whisper StoriesDocumento2 pagineSarees Whisper Storiesveesee12Nessuna valutazione finora

- ICT 10 q4 ModulesDocumento10 pagineICT 10 q4 ModulesJosmineNessuna valutazione finora

- Basic Porting - What To CutDocumento5 pagineBasic Porting - What To CutPratik Bajracharya Nepali100% (3)

- Getting Ripped EbookDocumento14 pagineGetting Ripped EbookBrent Koboroff100% (1)

- WWW Patreon COM Mrjetikkk: Pecial HanksDocumento18 pagineWWW Patreon COM Mrjetikkk: Pecial HanksИван КошкаревNessuna valutazione finora

- FOUA00143-00203-PPT-Green Network PlanningDocumento25 pagineFOUA00143-00203-PPT-Green Network PlanninggunteitbNessuna valutazione finora

- Samsung Echo-P Upgrade Module SchematicDocumento19 pagineSamsung Echo-P Upgrade Module SchematicNachiket Kshirsagar100% (1)

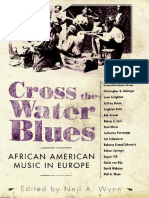

- Cross The Water Blues (1578069602)Documento302 pagineCross The Water Blues (1578069602)ameeeleee100% (4)

- TANGO Detailed PE Lesson Plan Teaches Basic Tango StepsDocumento10 pagineTANGO Detailed PE Lesson Plan Teaches Basic Tango StepsJanzen FrancoNessuna valutazione finora

- Phantom of The OperaDocumento61 paginePhantom of The OperaAmanda KrauseNessuna valutazione finora

- 48 Unique Cleric Domains For A Devotee of Every GodDocumento37 pagine48 Unique Cleric Domains For A Devotee of Every GodManuel OliverNessuna valutazione finora

- English Exam 2 BachilleratoDocumento4 pagineEnglish Exam 2 Bachilleratoradgull100% (2)

- Catálogo Tecno Plastic - Material IS PDFDocumento98 pagineCatálogo Tecno Plastic - Material IS PDFsalpica0174770% (1)

- Bai Tap Tieng Anh 6Documento32 pagineBai Tap Tieng Anh 6Nguyen GiangNessuna valutazione finora

- Soul Fuel CookbookDocumento126 pagineSoul Fuel Cookbookmelvin1995Nessuna valutazione finora