Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Government Information

Caricato da

Oscar AnaluisaDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Government Information

Caricato da

Oscar AnaluisaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

The impact of polices on government social media usage: Issues, challenges,

and recommendations

John Carlo Bertot, Paul T. Jaeger , Derek Hansen

College of Information Studies, University of Maryland, USA

a b s t r a c t a r t i c l e i n f o

Available online 3 November 2011

Keywords:

E-government

Social media

Policy

Access

Inclusion

Government agencies are increasingly using social media to connect with those they serve. These connec-

tions have the potential to extend government services, solicit new ideas, and improve decision-making

and problem-solving. However, interacting via social media introduces new challenges related to privacy,

security, data management, accessibility, social inclusion, governance, and other information policy issues.

The rapid adoption of social media by the population and government agencies has outpaced the regulatory

framework related to information, although the guiding principles behind many regulations are still rele-

vant. This paper examines the existing regulatory framework and the ways in which it applies to social

media use by the U.S. federal government, highlighting opportunities and challenges agencies face in imple-

menting them, as well as possible approaches for addressing these challenges.

2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Social media and government

Social media refers to a set of online tools that are designed for

and centered around social interaction. In practice, social media serves

as a catchall phrase for a conglomeration of web-based technologies

and services such as blogs, microblogs (i.e., Twitter), social sharing

services (e.g., YouTube, Flickr, StumbleUpon, Last.fm), text messag-

ing, discussion forums, collaborative editing tools (e.g., wikis), virtual

worlds (e.g., SecondLife), and social networking services (e.g. Facebook,

MySpace) (Hansen, Shneiderman, & Smith, 2011). These tools vary dra-

matically in their purposes and approaches, but they share an emphasis

on enabling users to communicate, interact, edit, and share content in a

social environment (Porter, 2008; Tepper, 2003). Unlike traditional

media, social media relies on user-generated content, which refers to

any content that has been created by end users or the general public

as opposed to professionals. Traditional media such as radio, books,

and network television is primarily designed to be a broadcast platform

(one-to-many), whereas social media is designed to be a dialogue

(many-to-many interaction) (Porter, 2008). This many-to-many inter-

action allows large groups of geographically dispersed users to produce

valuable information resources (Benkler, 2002), solve challenging

problems by tapping into unique and rare expertise (Brabham, 2008),

and gain diverse insights and perspectives through discussion.

While the term social media is relatively new, the idea of using

online tools to facilitate social interaction across time and space

has been with us for decades in the form of email lists, Usenet, and

Bulletin Boards. These early forms of social media showed that sur-

prisingly rich social worlds with their own unique cultures can

emerge through something as simple as text-based conversations

with strangers (Burnett & Bonnici, 2003; Burnett & Buerkle, 2004;

Smith & Kollock, 1999), particularly if those conversations can be

overheard by others (Hansen, 2009). Over time a range of new social

media services have emerged, each with its own unique architecture

that shapes the types of interactions that can occur (Lessig, 2006), as

well as the way user-contributed data is managed. Services differ in

their scope, the pace of interaction, the type of content being shared

(e.g., videos, images, text), who can control the data, the types of

connections between users and items, and data retention policies

(Hansen et al., 2011). Indeed, small changes in the design of social

media tools and policies around them can be vital to their success

and failure (Maloney-Krichmar & Preece, 2005; Preece, 2000). Despite

these differences, this paper focuses on social media as a group because

many of the regulations that affect one tool also affect other tools.

Social media technologies are nowregularly employed by a majority

of internet users. Among younger users, the use of these tools is nearing

universal, such as 86% of 1829 year olds using social media everyday

(Madden, 2010). Similarly, 72% of adults and 87% of teens use text

messages everyday (Lenhart, 2010). In July 2010, Facebook announced

that it had over 500 million users. As the number of users has increased

there has been a growing interest in applying social media toward

addressing national priorities (Pirolli, Preece, & Shneiderman, 2010),

not just using them for entertainment or corporate purposes.

President Obama became a strong advocate for the use of social

media when he was presidential candidate Obama. A great deal of

fundraising and organizing success of the Obama presidential campaign

Government Information Quarterly 29 (2012) 3040

Corresponding author at: 4105 Hornbake Building, College of Information Studies,

University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742-4345, USA. Fax: +1 301 314 9145.

E-mail addresses: jbertot@umd.edu (J.C. Bertot), pjaeger@umd.edu (P.T. Jaeger),

dhansen@umd.edu (D. Hansen).

0740-624X/$ see front matter 2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.giq.2011.04.004

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Government Information Quarterly

j our nal homepage: www. el sevi er . com/ l ocat e/ govi nf

was tied directly to the extensive use of social media by the campaign

(Jaeger, Paquette, & Simmons, 2010). Both at the behest of the Obama

administration and as a natural outgrowth of the frequent use of

social media by individuals, federal government agencies have en-

thusiastically embraced the use of social media for government

purposes.

Government employment of social media offers several key op-

portunities for the technology (Bertot, Jaeger, Munson, & Glaisyer,

2010):

Democratic participation and engagement, using social media tech-

nologies to engage the public in government fostering participatory

dialogue and providing a voice in discussions of policy development

and implementation.

Co-production, in which governments and the public jointly develop,

design, and deliver government services to improve service quality,

delivery, and responsiveness.

Crowdsourcing solutions and innovations, seeking innovation through

public knowledge and talent to develop innovative solutions to large-

scale societal issues. To facilitate crowdsourcing, the government

shares data and other inputs so that the public has a foundational

base on which to innovate.

Though not mutually exclusive, these opportunities offer great

promise and pose new challenges in redening government-

community connections and interactions. As government social media

initiatives are launched and evaluated, design lessons can be extracted

and shared to achieve these and related goals (e.g., Johnston & Hansen,

in press).

Much government activity is now focused on social media, with so-

cial media becoming a central component of e-government in a very

short period of time (Bertot, Jaeger, & Grimes, 2010a, 2010b, in press;

Bertot, Jaeger, Munson, & Glaisyer, 2010; Chang & Kannan, 2008;

Drapeau & Wells, 2009; Noveck, 2008; Osimo, 2008; Snyder, 2009). U.S.

federal agencies have been using blogs, microblogs, wikis, and social

networking sites (Godwin, 2008; Laris, 2009), and even virtual worlds

(Miller, 2009), among other social media, to create records,

disseminate information, communicate with the public and between

agencies for several years (Barr, 2008; Hanson, 2008; Snyder, 2009;

Wyld, 2008). The General Services Administration has even created a

standard agreement for social media providers to allowfor government

usage of social media services. The Obama administration has made a

priority of the use of social media technologies, and the new Federal

Chief Information Ofcer is strongly encouraging the expansion of

these activities (Lipowicz, 2009; Thibodeau, 2009).

Not only is the Obama administration strongly encouraging agen-

cies to use social media to provide information, communicate with

members of the public, and distribute services, it has also made a

priority of public usage of social media to participate in government

(Jaeger & Bertot, 2010; Jaeger, Paquette, & Simmons, 2010). And

many members of the public already expect that government ser-

vices will be available electronically and that government agencies

will be accessible via social media technologies (Jaeger & Bertot,

2010). The widespread adoption of these social media tools has

been emphasized in a number of different White House reports,

such as the 2009 report entitled Open Government: A Progress Report

to the America People, which discuss how social media is being used

by agencies to promote transparency.

Though agencies are increasing their use of social media technolo-

gies as a way to extend government services, further reach individ-

uals, offer government information, and engage members of the

public in government efforts, agencies are in large part doing so

through an antiquated policy structure that establishes the parame-

ters for information ows, access, and dissemination. The next section

of the paper discusses this policy environment as it applies to social

media technologies.

2. Government social media usage and the law

Federal information policies can come from a large number of

sources, including legislation, regulations as contained in the Code

of Federal Regulations, directives (such as the Open Government

Directive issued by the Ofce of Management and Budget, which

mandated that agencies create an open government plan), Circu-

lars, and Executive Orders. Though there is a range of reasons why

these policies exist, information policies primarily govern issues of

safety, trust, security, ownership rights, social inclusion, participa-

tion, and record keeping. Within these broader topics are critical

areas related to privacy, e-participation and democratization, access,

and engagement.

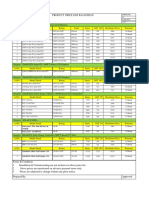

Table 1 presents selected policies and their requirements as they

impact federal agency use of social media in terms of three key policy

objectives. While these policy instruments predominantly predate

the existence of social media, their reach extends to agency interac-

tion with and use of social media technologies. And yet, agencies

largely do not consider these policy instruments when using social

media. In many cases, the social media technologies have been imple-

mented without regard even to the policy goals in Table 1. In April

2010, the Ofce of Management and Budget (OMB) issued a memoran-

dum on social media, Web-based interactive technologies, and paper-

work reduction. The memo focused on agency use of social media in

relation to the requirements of the Paperwork Reduction Act (PRA),

trying to ensure that agencies complied with the requirements of the

PRA, which are detailed below. However, major policy goals of access,

inclusion, privacy, security, accuracy, archiving, and copyright have

yet to be addressed. The relationships of these policies to social media

are explored below in light of each of the policy goals. Appendix A

provides a detailed description of many of the policies related to

social media usage by government.

2.1. Access and social inclusion

For government use of social media to increase access to govern-

ment information and services and to successfully facilitate civic par-

ticipation, members of the public must be able to access and use

Table 1

Selected information policies by objective.

Policy objectives related

to social media

Selected relevant policy instruments

Access and

social inclusion

Americans with Disabilities Act

Executive Order 13166Improving Access to Services

for Persons with Limited English Prociency

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act

Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act

Telecommunications Act of 1996

Privacy, security,

accuracy, and archiving

Children's Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA)

Federal Information Security Management Act

(FISMA)

Information Quality Act

OMB Memo M-03-22 (Guidance for Implementing

the Provisions of the E-government Act of 2002)

OMB Memo M-04-04 (E-Authentication Guidance for

Federal Agencies)

OMB Memo M-05-04 (Policies for Federal Agency

Websites)

Federal Depository Library Program (Title 44 USC)

Governing and

governance

E-government Act of 2002

OMB Circular A-130 (Management of Federal

Information Resources)

Paperwork Reduction Act

Various Copyright (Title 17 USC) and Patent &

Trademark (Title 35 USC) legislation

31 J.C. Bertot et al. / Government Information Quarterly 29 (2012) 3040

social media technologies. Several policy instruments are directly

related to access and inclusion in social media. And, the ability to

use social media technologies by the public is predicated on the fol-

lowing (Bertot, Jaeger, Munson, & Glaisyer, 2010):

1) Access to the technologies (which at a minimum necessitates a

device and internet access at a speed sufcient to support social

media content);

2) The development of technology, programs, and internet-enabled

services that offer equal access to all users; and,

3) Information and civics literacy necessary to understand govern-

ment services, resources, and operations.

For example, Executive Order 13166Improving Access to Services

for Persons with Limited English Prociency requires that agencies

provide appropriate access to persons with limited English pro-

ciency, encompassing all federally conducted programs and activi-

ties, including using social media technologies to communicate and

collaborate with members of the public. This policy objective is

meant to address the fact that there are highly pronounced gaps in

e-government usage among people who predominantly speak a

language other than English, as little e-government content is avail-

able in non-English formats; for example, 32% of Latinos who do not

speak English use the internet, but 78% of Latinos who speak English

use the internet (Fox & Livingston, 2007).

Many of these policies focus on access for people with disabilities,

as they are the most disadvantaged population in the United States in

relation to computer and internet access (Jaeger, 2011). Percentages

of computer and internet usage have remained at levels approxi-

mately less than half of the equivalent percentages for the rest of

the population since the advent of the Web (Dobransky & Hargittai,

2006; Jaeger, 2011; Lazar & Jaeger, 2011). Several of the instruments

that would seem to guarantee access to government use of social

media for persons with disabilities result from the broad protections

of disabilities rights laws. The Individuals with Disabilities Educa-

tion Act requires equal access to all electronic materials used in pub-

lic education. The Americans with Disabilities Act provides broad

prohibitions on the exclusion of persons with disabilities from gov-

ernment services and benets, including communication with the

government. Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act creates broad

standards of equal access to government activities and information

for individuals with disabilities, which includes content distributed

via social media, and establishes general rights to accessible infor-

mation and communication technologies, which includes social

media tools.

Other laws focus more directly on information and communica-

tion technology usage by the government. The Telecommunications

Act of 1996 promotes the development and implementation of acces-

sible information and communication technologies used online. Most

directly, Section 508 requires that electronic and information tech-

nologies purchased, maintained, or used by the federal government

meet certain accessibility standards designed to make online infor-

mation and services fully available to people with disabilities. Agen-

cies, as well as entities receiving federal funding, implementing social

media technology-based services must pay particular attention to

complying with the requirements of Section 508. Agencies employ-

ing non-Federal services to provide social media technology capabil-

ities are also required to ensure that persons with disabilities have

equivalent access to the information on these third party sites as

required in Section 508.

Social media companies rarely consider the accessibility require-

ments of Section 508, yet this inaccessibility has not been a deterrent

to the use of social media by government agencies. For persons with

disabilities, social media often means a reduced ability to participate.

For example, recent studies have found that the accessible version

of Facebook has fewer features and greatly reduced usability and

functionality, considerably limiting the utility and usefulness of the

site for users with disabilities (Lazar & Wentz, 2011; Wentz & Lazar,

2011). As many social media tools are inaccessible to people with

disabilities, and websites increasingly embed social media technolo-

gies within them, the accessibility of websites has steadily

decreased (Carlson, 2004; Harper & DeWaters, 2008). While future

technological developments may overcome such inaccessibility,

the current situation causes concern for inclusion of people with

disabilities in government use of social media.

2.2. Privacy, security, accuracy, and archiving

Social media technologies raise a large number of information

management issues, primarily in the areas of privacy, security, accu-

racy, and archiving, spanning major issues such as personally identi-

able information, security of government data and information,

and the accuracy of publicly available data. By adopting the use of

specic social media tools, government agencies appear to be tacitly

endorsing the privacy, security, and other policies employed by those

social media providers as adequate.

Some of the related policies are very specic and tailored to

the online environment. For example, the Children's Online Privacy

Protection Act (COPPA) prohibits the collection of individually iden-

tiable information from children under the age of 13. However, the

majority of related policy instruments address these issues in a

broad, non-specic fashion, which may include social media con-

texts within their broad scope. Overall, these policy instruments

address many issues of information management related to social

media, but fail to sufciently address at an operational level many

important issues of information management impacted by social

media.

OMB Memo M-04-04 (E-Authentication Guidance for Federal

Agencies) mandates that agencies decide the appropriate levels of

openness, moderation, authentication, and attribution, balancing

access, identity authentication, attribution, and concern for author-

itative sourcing in the level of moderation that is needed on an

agency website. To accomplish this, agencies must perform a stan-

dardized risk assessment on all applications they put online. Simi-

larly, the Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA)

requires a Certication and Accreditation (C&A) process for all

federal information technology systems that utilize social media

technologies. Further, this C&A activity must be performed by an

independent third party auditing team and must conform to the

Risk Management Framework of the National Institute of Standards

and Technology.

The Information Quality Act (passed into law in 2001) requires

agencies to maximize the quality, objectivity, utility, and integrity of

information and services provided to the public. The Act came into

effect prior to the development and use of prevailing social media

technologies; nonetheless, agencies must ensure reasonable suit-

able information and service quality strategies consistent with the

level of importance of the information that include clearly identify-

ing the limitations inherent in the information dissemination prod-

uct (e.g., possibility of errors, degree of reliability, and validity) and

taking reasonable steps to remove the limitations inherent in the

information.

Under OMB Memo M-03-22 (Guidance for Implementing the

Provisions of the E-government Act of 2002), federal public web-

sites, including those using social media technologies, are required

to conduct privacy impact assessments, post privacy policies in a

standardized machine-readable format on each website, and post a

Privacy Act Statement that describes the Agency's legal authority

for collecting personal data and how the data will be used. Addition-

ally, federal websites are prohibited from using persistent cookies

and other web tracking methods unless an Agency head or designated

Agency sub-head approved their use for a compelling need. In such

cases, agencies must post clear notice of the nature of the information

32 J.C. Bertot et al. / Government Information Quarterly 29 (2012) 3040

collectedinthe cookies, the purpose and use of the information, wheth-

er or not and to whom the information will be disclosed, and the

privacy safeguards applied to the information collected. The Privacy

Act did not envision a time in which people would be voluntarily

communicating with government agencies in digital open spaces

like Twitter.

When government websites become two-way communities, it

opens the possibility of virus and other attack agents being inserted

into the government environment, as well as the possibility of unin-

tended release of information. OMB Memo M-05-04 (Policies for

Federal Agency Websites) requires that agencies provide adequate

security controls to ensure information is resistant to tampering,

to preserve accuracy, to maintain condentiality as necessary, and

to ensure that the information or service is available as intended

by the Agency and as expected by users. This memo raises issues

in several different social media contexts. Many social media services

are hosted outside government websites (e.g., Facebook, Twitter,

YouTube). Under this memo, agencies are required to establish

and enforce explicit Agency-wide linking policies that set out

management controls for linking beyond the Agency to outside

services and websites. This memo establishes that providing dis-

claimers detailing the level of moderation found on third party

sites is appropriate on these notication screens, while pop-up or

intermediary screens should be used to notify users that they are

exiting a government website. Additionally, many social media

services allow users to take data from one website and combine

it with data fromanother, commonly referred to as mashups. According

to this memo, agency public websites are required, to the extent practi-

cable and necessary to achieve intended purposes, to provide all data in

an open, industry standard format that permits users to aggregate,

disaggregate, or otherwise manipulate and analyze the data to

meet their needs.

The presence of a related policy, however, does not guarantee the

application of a solution to an information management issue raised

by social media. For over 150 years, the Government Printing Ofce

(GPO) has served as the lead and coordinating agency in conjunction

with the Federal Depository Library Program (FDLP)a network of

nearly 150 full, partial, and regional Depositories. This collaborative

network has served as the primary means for providing community

access to government information. However, the ability of social

media to provide direct constituent and government interactions

raises major challenges for the comprehensive collection and dissem-

ination of government information. Digitization is transforming the

FDLP structure and the nature of government interactions with con-

stituents. As social media technologies are increasingly deployed by

government agencies, responsibility for codifying, disseminating, and

providing access to ofcial government information remains an

unanswered question (Jaeger, Bertot, & Shuler, 2010; Shuler, Jaeger, &

Bertot, 2010). While responsibilities for archiving social media interac-

tions remain unaddressed, much of this information disappears.

This situation also means that there decreasingly exists a perma-

nent and nal document, upon which nearly all records manage-

ment and archiving efforts are built (Bertot, Jaeger, Munson, & Glaisyer,

2010). By using third party applications and software that reside on

non-governmental information systems, data ownership, records sched-

ules, and archiving are signicant issues. To address these issues, agen-

cies could begin working in collaboration with the National Archives

and Records Administration (NARA), the GPO, and the FDLP libraries to

ensure the permanency of the public record regarding social media tech-

nologies. This will be particularly signicant as the policy making and

public comment process migrates increasingly to online venues.

2.3. Governing and governance

Policy instruments also establish the parameters of governing

and governance. These instruments provide broad principles and

guidance for agencies, but fail to address the use of social media, as

nearly all pre-date the development and use of social media technol-

ogies. Much of such guidance is encapsulated in OMB Circular A-130

and the PRA establish principles that:

Agencies are required to disseminate information to the public in a

timely, equitable, efcient, and appropriate manner.

Agencies are required to establish and maintain Information Dis-

semination Product Inventories.

Agencies must consider disparities of access and how those without

internet access will have access to important disseminations.

Agencies should develop alternative strategies to distribute

information.

When using electronic media, the regulations that govern proper

management and archiving of records still apply.

Agencies need to evaluate and determine the most appropriate

methods to capture and retain records on both government servers

and technologies hosted on non-Federal hosts.

Agencies are required to provide members of the public who do not

have internet connectivity with timely and equitable access to in-

formation, for example, by providing hard copies of reports and

forms.

When considering these principles in light of social media tech-

nologies, a range of issues surface, such as: the need for alternative

dissemination strategies for access to and dissemination of govern-

ment information and services; the need for ubiquitous access to

internet-embedded information content; and the need to consider

records management, archiving, and preservation. While social media

technologies have the potential to reach a large percentage of the pub-

lic, social media technologies can also exclude users without internet

access, including economically disadvantaged persons, from receiving

such information. Also, some social media technologies require high-

speed internet access and bandwidth, which may not be available in

rural areas or may be unaffordable.

The E-government Act of 2002 also established several related

standards for e-government that inform the use of social media by

government agencies, such as: developing priorities and schedules

for making government information available and accessible to the

public; posting inventories on agency websites; publishing annual

reports on inventories, priorities, and schedules; complying with

requirements of Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act in all online

activities; and implementing and maintaining an Information Dis-

semination Management System.

Though not exhaustive, the above sections demonstrated that

there is a substantial disconnect along several issue areas between

existing information policies and government use of social media

technologies. While one may argue that agencies should continue to

forge ahead with the adoption and use of social media due to their

ability to offer government services where individuals increasingly

are with their online usage, there is a need to update the information

policy context to better guide agenciesas well as set security, priva-

cy, and other parameterswith social media technologies.

3. Gaps in existing policy and attempts to address them

The unique nature of social media technologiesand the basis of

their mass appeal and strength as a government toollies in their

ability to create an immediate and interactive dialogue. But this na-

ture also creates important policy challenges as these technologies

continue to be used more extensively both by governments and the

public. Though the current policy environment addresses many issues

of privacy, security, accuracy, and archiving in some detail, much of

the policy related to the use of social media predates the creation of

social media technologies. As a result, many of the existing policies

do not adequately address the technological capacities, operations,

or functions of social media. Further, as social media provide new

33 J.C. Bertot et al. / Government Information Quarterly 29 (2012) 3040

ways to combine previously unavailable and/or separately maintained

data, there are now cross-dataset concerns that impact multiple policy

issues. Finally, it is important to consider that social media services

are private ventures with their own acceptable use, data use, acces-

sibility, and privacy policies that often do not conform to federal

requirements.

Consider the following issues related to social media that are par-

tially addressed or not addressed at all by current policy:

Ensuring information disseminated through social media is consis-

tently available;

Making information available through social media available in

other formats for those who lack equal access due to infrastructure,

ability, language, or literacy;

Maintaining consistency of access for government agencies and for

members of the public;

Archiving information disseminated through social media for per-

manent access and retrieval;

Preventing release of sensitive or secret information;

Fostering transparency and accountability, through which govern-

ment is open and transparent regarding its operations to build

trust and foster accountability;

Ensuring the security of personally identiable information;

Maintaining security of user information;

Providing a continuously updated data.gov registry, with an histor-

ical index that shows current and past data availability;

Ensuring that third-party social media technology providers (e.g.,

Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Second Life) adhere to government

privacy, security, and accuracy policies and requirements;

Ensuring that individual-government transactions that transpire

through social media technologies are condential, private, and/or

secure as required by federal laws and policies;

Ensuring continuity of service, especially when technologies sun-

set. For example, Yahoo announced the discontinuation of its de-

licious tagging service (http://www.readwriteweb.com/archives/

rip_delicious_you_were_so_beautiful_to_me.php).

Ensuring that mashups and other forms of data integrationan in-

creasing activity due to data availability via data.govdo not lead

to user prole development that invades privacy or otherwise com-

promises individuals, national security, or agency data security;

Monitoring the storage of government information when held off-

site through cloud computing services. Allowing private companies

to maintain potentially sensitive government data raises enormous

questions of data retrieval, accuracy, and permanence, as well as

opens up signicant opportunities for misuse of data by providers

or attempts by other governments to access the data based on the

geographic location of the server farms where the data are main-

tained; and

Ensuring that social media technologies are not the only means of

getting a response from an agency.

This list is by no means exhaustive, and each type of social media

technology raises its own specic set of policy issues.

The Obama Administration is aware of and trying to address at

least some of these policy shortcomings. Since April 2010, OMB has

issued three signicant memos regarding Federal agency use of and

interaction with social media technologies: 1) M-10-22 (Guidance

for Online Use of Web Measurement and Customization Technolo-

gies); 2) M-10-23 (Guidance for Agency Use of Third-Party Websites

and Applications); and an unnumbered memo issued on April 7,

2010 by Cass Sunstein entitled Social Media, Web-Based Interactive

Technologies, and the Paperwork Reduction Act.

Memo M-10-22 (Guidance for Online Use of Web Measurement

and Customization Technologies) broadens the denition of tracking

technologies to now include all web measurement and customiza-

tion technologies, even going so far as to explicitly state that this

guidance is not limited to any specic technology or application

(such as persistent cookies). More signicantly, it explicitly promotes

the use of these measurement and customization technologies to

achieve some of the benets other sites that use them enjoy including

website analytics and customization of the user experience. This is

consistent with the other memos by the Obama administration

that emphasize the benets or perceived benets of enabling the

use of social media technologies. There are still prohibitions such

as tracking individual-level activity outside of the website, sharing

the data with other departments or agencies, and cross-referencing

the data with personally identiable information. To safeguard users,

notication of the ability to opt out or opt in must be provided, along

with additional information in the privacy policy. However, despite

the prohibitions and safeguards, the message of allowing these

technologies that are becoming increasingly important to social

media tools comes through clearly.

OMB Memo M-10-23 (Guidance for Agency Use of Third-Party

Websites and Applications) accounts for the increasing amount of

internet activity that occurs on third-party sites such as Facebook,

Twitter, YouTube, and other social media. Like OMB Memo M-10-

22, the focus is on protecting participants' privacy, but in the context

of third parties. While some earlier memos touched on websites

hosted by contractors or data held by third parties (e.g., M-03-22),

the default assumption was that government agencies were in com-

plete control of the content and data management activities on the

sites.

Government agencies interact via the internet in several ways

with third parties. As specic social media sites such as Facebook

have become important platforms for information exchange, govern-

ment agencies have created a presence on them. Agencies have also

begun including third party widgets, modules, snippets, and plug-

ins on their own websites. These are mini applications with dynamic

content or services that are embedded within another web page. Fi-

nally, many social media and related sites offer Application Pro-

gramming Interfaces (APIs) that allow other programs and sites to

call upon their content and services. These support mashups that

combine data from different sources into an integrated user experi-

ence, such as a Google Map that has user-generated content on

nursing homes overlaid onto it.

The content of OMB Memo M-10-23 builds on a number of exist-

ing policies. There is a strong emphasis on privacy policies, Privacy

Impact Assessments (PIAs), and the role of the Senior Agency Ofcial

for Privacy (SAOP), all of which were discussed in prior memos (e.g.,

M-03-22). These regulatory forms are all expanded upon in this

memo to specically deal with the new questions raised by agen-

cies' use of these new types of third party sites and services. For ex-

ample, agencies with a presence on third party sites must provide a

Privacy Notice, which is a brief description of how the agency's Pri-

vacy Policy will apply in a specic situation such as the use of a

third party site that has its own privacy policies. Finally, agencies

are still encouraged to link to or otherwise alert (e.g., through the

use of pop-up windows) users when they link to a third party website

that is not part of the government domain.

The Memorandum (Social Media, Web-Based Interactive Tech-

nologies, and the Paperwork Reduction Act) written by Cass Sun-

stein on April 7, 2010 claries when and how the Paperwork

Reduction Act of 1995 (the PRA) applies to Federal agency use of so-

cial media and web-based interactive technologies. The memoran-

dum's primary aim is to clarify that certain uses of social media

and web-based interactive technologies will be treated as equivalent

to activities that are currently excluded from the PRA. The memo is

needed because the vagueness of the original law that species that

the PRA applies to the collection of information regardless of form

or format, but does not dene information. Later OMB regulations

excluded three types of activities discussed in the memo that were

not considered information: general solicitations, public meetings,

and like items.

34 J.C. Bertot et al. / Government Information Quarterly 29 (2012) 3040

The memo discusses each of these three exclusions, explaining

how certain social media activities fall within them. For example:

The memo explains that the PRA does not apply if social media tools

are used to solicit general comments from the public (i.e., open-

ended responses to questions) rather than answers to specic

closed-ended survey questions under the general solicitations

exclusion.

The memo indicates that, through the public meetings exclusion,

most regular social media activity is exempt from the PRA since

OMB considers interactive meeting toolsincluding but not limit-

ed to public conference calls, webinars, blogs, discussion boards, fo-

rums, message boards, chat sessions, social networks, and online

communitiesto be equivalent to in-person public meetings.

The memo identies like items that are not information and

thus not covered by the PRA. These include: 1) email addresses,

usernames, passwords, and geographic locations gathered for ac-

count registration; 2) items collected to help navigate or customize

a website; 3) ratings and rankings; and 4) items necessary to com-

plete a voluntary commercial transaction, and contests, so long as

they do not take the form of structured responses.

Even with the guidance provided by OMB, however, there remain

a number of policy gaps in a range of areas. The area of access and in-

clusion provides a good example of how these different unanswered

questions in the policy environment can fail to address the ways in

which entire populations can be cut out of the use of social media

to interact with government. Technological developments often ben-

et the already-technologically privileged (Corbridge, 2007; Hanson,

2008; Mackenzie, 2010). Government use of social media seems to

favor access for those who already have access to other technological-

ly-based means of government interaction.

As discussed above, disabilities and language can be barriers to ac-

cess and usage of government social media services. These are not the

only groups in this position of potential disenfranchisement, however.

By shifting away fromwhat were more familiar and accessible methods

of information communication, and interaction, the use of social media

can also distance users with limited technological literacythe under-

standing of how to use technologies like computers and the internet.

As lower levels of technological literacy are generally linked to lower

levels of formal education and lower levels of ability to adapt to new

technologies, users with lower technological literacy may be intimidat-

ed or driven from participation by social media (Jaeger & Thompson,

2003, 2004; Powell, Byrne, & Dailey, 2010).

4. Future directions

None of these policy gaps or questions that need further investiga-

tion is presented as reasons for government to reduce or avoid the

use of social media. Indeed social media offers opportunities to pro-

vide newgovernment functions and to invigorate established govern-

ment functions, such as transparency (Bertot, Jaeger, & Grimes,

2010a, 2010b, in press). Instead, they are raised as issues to consider

and address as social media becomes an increasing central aspect of

presenting government information, connecting to government ser-

vices, and engaging members of the public in governance and civic

discourse.

While the role of social media technologies in government infor-

mation services is still coalescing, there is time to analyze and re-

search the standing of social media within the larger policy context

and the changes that are necessary in the policy environment to en-

sure the success of the new technology. Table 2 below presents a

set of policy and research questions related to the three key policy ob-

jectives discussed above, as well as two other essential areas for fu-

ture consideration in research and policy: Social Media Use and

New Democratic Models. These questions are not meant to be com-

prehensive, but instead to point to the range of important issues

that require further examination in relation to the government use

of social media.

Social media technologies are not the rst new technological devel-

opment that government agencies have adopted before consideration

of existing policy requirements and goals. The implementation of new

technologies tends to depoliticize change by technologizing it, thereby

muting questions of power, inequality, or exclusion (Mackenzie, 2010,

p. 183). Often, the quick adoption of new technologies has overridden

other concerns, such as the rapid, yet uncoordinated, implementation

of government agency websites that has resulted in the United States

government being the largest provider of content online, yet lacking a

uniform look or function to its sites the way that other governments

do. Similarly, the decade-plus struggles inthe adoption and deployment

of broadband nationally despite a series of interventions provide anoth-

er cautionary example for the implementation of social media without

adequate consideration of the overall policy context (Paquette, Jaeger,

& Wilson, 2010).

Bringing social media usage by government agencies in line with

existing policies is a rst essential step in the ongoing usage of social

media with other government goals. And these policies must be un-

derstood within the broader policy and information contexts, as the

government is more than an allocator of services and values; it is

an apparatus for assembling and managing the political information

associated with expressions of public will and with public policy

(Bimber, 2003, p. 17). The aforementioned recent memos issued by

OMB are a rst attempt to move the federal government's policies to-

wards encompassing social media technologies. But these memos are

incremental and do not address the larger policy modication needs.

To navigate the discrepancies between traditional information poli-

cies that govern government information ows, access, and interac-

tion, one suggested solution is a process of harmonization (Bertot,

Jaeger, Shuler, Simmons, & Grimes, 2009; Jaeger, Bertot, & Shuler,

2010; Shuler, Jaeger & Bertot, 2010). Though the concept of harmoni-

zation has been proposed as an approach for e-government informa-

tion generally, it can be especially useful within the context of social

media. Such harmonization should be based on using the long-estab-

lished core democratic principles such as:

Fostering an engaged and informed public. Embedded deeply with-

in the founding of the United States is access to government infor-

mation, beginning with the Declaration of Independence itself

and continuing through to e-government programs today (Jaeger

& Bertot, 2011). This principle has existed in particular through

more than 150 years through the Federal Depository Library Program

(FDLP), through which the federal government and over 1200 librar-

ies collaborate to provide access to and disseminate a wide range of

government information to ensure an informed public. Fundamental-

ly, it is essential for the public to have ready access to government in

order to participate in democratic activities.

Extending services and resources to where the public is. A key

aspect of the FDLP, the establishment of agency regional ofces,

courts, and other government outposts are mechanisms to

embed and make available federal government services at more

local levelsthereby putting government closer to people and

communities.

Participatory democracy. Our government includes a number of

means through which the public can participate in democratic ac-

tivitiestestimony at hearings, responses to regulation solicitations,

contacting and interacting with elected ofcials, to name a few. The

interaction between the public and government ensures that gov-

ernment remains of the people, for the people.

Transparency and openness. The requirement that government

make its information, data, and processes public and readily acces-

sible provides accountability, an enhanced ability of the public to

see into the workings of government, and the information to voice

concerns about these workings, when necessary.

35 J.C. Bertot et al. / Government Information Quarterly 29 (2012) 3040

Equity of access. A prevalent thread that weaves the nation's informa-

tion policies is ensuring that the public, regardless of socio-economic

status, geographic location, disability, availability of telecommunica-

tions technologies, or other factors that can contribute to gaps in

access to information.

Ensuring permanent access for an informed public. The archiving

of government information is designed to ensure permanent access

to the government recordregardless of how that information is

created, stored, or retrieved.

These principles stretch back to the foundation of the Republic, as

James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay argued for these

concepts in the Federalist Papers (1789) with the vision of a constitu-

tional government would be the center of information in the new

nation. In fact, information and communication appear as important

concepts in 31 of the 85 essays in the Federalist Papers, with authors

believing that information would both help link people to the process of

governance and simultaneously prevent the formation of tyrannical

majorities. These same principles also serve as a starting point for the

harmonization process across the policies identied in this article.

In addition to utilizing a harmonization perspective to frame the

government use of social media, the existing policies outlined above

and detailed in Appendix A must receive greater attention in the

decisions by agencies to use social media technologies. In many

cases, the agencies may not even be aware of the range of related

policies and the implications of those policies. An important rst

step would be the creation of a guide that would provide clear guid-

ance to all agencies about the policies that must be considered in

the adoption and use of social media. GSA (2010) has created a so-

cial media handbook, but there is need for a cross-agency social

media guide specically devoted to the relevant policies and their

implications. Prior to proposing new policies to specically address

government use of social media, an explicit set of social media

guidelines that encompasses all existing policies would help to clar-

ify whether new policies are needed and what issues new policies

would need to address.

A further important step would be building on social media usage

as the impetus for examining the responsiveness of policy to techno-

logical change. For example, as agencies began adopting cloud com-

puting services several years ago, this adoption raised many issues

Table 2

Key policy and research questions related to social media and policy objectives.

Policy objectives related

to social media

Key policy and research questions

Social Media Use What tools and approaches best promote exchange between governments and users?

What mix of technologies, data, and information promote, support, and foster user engagement?

What technologies provide the best ways to display content to users for informed participation?

How can designers promote exposure to diverse viewpoints? What are individual preferences for opinion diversity in information access?

How can agencies best incorporate social media-produced feedback into policy and decision-making?

How can governments create sustainable social media technology strategies and efforts?

Access and social inclusion What tools and approaches best promote universal access to social media technologies?

How do we ensure that social media technologies are inclusive, rather than exclusive?

Are there social media technologies that can facilitate access to persons with disabilities?

What mechanisms (e.g., partnerships, collaborations) can promote access to and participation in social media technologies to all members of

society?

How can agencies leverage partnerships to extend social media applications and use within communities across the country?

What types of partnerships best promote use of and interaction with government through social media technologies?

How can agencies and organizations develop mutually benecial partnerships?

What organizational, management, and operational structures are necessary to create successful partnerships?

Privacy, security, accuracy,

and archiving

How will agencies ensure the privacy of individuals, particularly when data may not be owned by government agencies?

What data and information search tools are necessary to facilitate access to and location of government data?

What review processes are required prior to government data dissemination through open government initiatives such as data.gov to ensure

privacy, security, and accuracy?

What data validity, reliability, and quality check processes could be adopted in order to ensure appropriate uses, combinations, and

extrapolations of combined government (and other) datasets?

What cybersecurity measures, tools, and approaches are necessary to ensure national, agency, and individual security?

What tools and applications do agencies need to archive and preserve their social media-based activities?

What is the document that agencies preserve based on their social media activities?

What policies and procedures are necessary to govern the scheduling and archiving of government social media activities?

What is the role of GPO and the FDLP, if any, in the social media technology environment of the federal government?

Governing and governance How do we build social and political trust?

Who/what makes decisions on what authority?

What collaborative governance processes and structures do social media technologies enable?

What policy structures and frameworks are necessary to govern government use of and interaction with social media technologies?

In what ways can the federal government harmonize across a range of policy instruments to comprehensively account for the evolving policy

context of social media technologies?

How will social media technology change how policy is developed?

Will social media technology privilege certain types of policy substance over others?

Will social media technology result in new policies that rely on the existence of social media to be viable?

What policy barriers to using social media technologies exist, and how do we resolve those policy impediments?

How do we create policies that encourage the use of social media technologies?

How can agencies and governments incorporate the results of social media technology use into agency strategies, goals, objectives, services, and

resources?

What review and analysis processes should agencies develop to assess social media-based participatory feedback and solicitations into agency

workows?

New Democratic Models What do we mean by the term transforming democracy?

What possible scenarios both positive and negative can be envisaged?

What are the opportunities and limits on transformations that are compatible with the U.S. constitution, the precedents in the eld of

administrative law, political norms and traditions?

What are the limits or parts of our system that should be prioritized?

What transformations could solve problems with our existing structures, and where are the biggest benets to be had?

36 J.C. Bertot et al. / Government Information Quarterly 29 (2012) 3040

that policy wasand remainsunready to successfully address (Jaeger,

Lin, & Grimes, 2008; Jaeger, Lin, Grimes, & Simmons, 2009; Paquette,

Jaeger, & Wilson, 2010). When the adoption of new technologies by

government agencies challenges relevance of current information poli-

cy, it is a clear indicator that the policy development and renement

process is not eet enough for the current environment of rapid techno-

logical change that seems likely to continue into the foreseeable future.

As new technologies that are currently unimagined will continue to

emerge and be adopted by government agencies, the development of

more responsive information policies that are based on principles that

are not tied to specic technologies will be a vital step in ensuring

that policies can remain relevant and useful to government agencies

and members of the public.

Social media technologies have already taken an important place

among means of communication between government and members

of the public and are poised to continue to take on greater promi-

nence as a mechanism of government information and services are

more content moves onto this platform and more users come to ex-

pect to use social media as a primary method to interact with govern-

ment. At its best, social media has the potential to simultaneously

make government more reachable, available, and relevant to users,

while offering users more opportunities to become actively engaged

in government. To ensure that social media technologies enable

some or all of this lofty potential, the policy issues related to social

media must be closely examined and addressed while the uses of

the technologies are still developing and evolving.

Policy instrument Policy type Description

OMB Memo M-05-04 Memo When government websites become two-way communities, it opens the possibility of

viruses and other attack agents being inserted into the government environment. Many of

the security policies in OMB Memo M-05-04 have implications for Web 2.0 technologies:

Policies for Federal Agency Websites

Agencies are required to provide adequate security controls to ensure information is

resistant to tampering, to preserve accuracy, to maintain condentiality as necessary,

and to ensure that the information or service is available as intended by the Agency and

as expected by users.

Many social media services are hosted outside government websites (e.g., Facebook,

Twitter, YouTube):

Agencies are required to establish and enforce explicit Agency-wide linking

policies that set out management controls for linking beyond the Agency to outside

services and websites.

Disclaimers detailing the level of moderation found on third party sites are often

appropriate on these notication screens.

Pop-up or intermediary screens should be used to notify users that they are

exiting a government website.

Many social media services allow users to take data from one website and combine it

with data from another, commonly referred to as mashups:

Agency public websites are required, to the extent practicable and necessary to

achieve intended purposes, to provide all data in an open, industry standard format that

permits users to aggregate, disaggregate, or otherwise manipulate and analyze the data

to meet their needs.

Agencies need to ensure that these open industry standard formats are followed

to maximize the utility of their data.

OMB Memo M-04-04 Memo Agencies must decide the appropriate levels of openness, moderation,

authentication, and attribution that require a balance between access, identity

authentication, attribution, and concern for authoritative sourcing in the level of

moderation that is needed on a site.

E-Authentication Guidance for

Federal Agencies

Requires Agencies to perform a standardized risk assessment on all applications

they put online. The risk assessment also identies the Level of Assurance (LOA) of

identity the application should require from an end user's identity credential (userID/

password pair, digital certicate or other identity management technology).

OMB Memo M-10-22 Memo Federal public websites, including those using social media technologies, are

required to conduct privacy impact assessments, post privacy policies on each

website, post a Privacy Act Statement that describes the Agency's legal authority for

collecting personal data and how the data will be used.

Guidance for Online Use of Web Measurement

and Customization Technologies

Agencies must post privacy policies in a standardized machine-readable format

such as the Platform for Privacy Preferences Project.

Federal websites are prohibited from using persistent cookies and other web

tracking methods unless an Agency head or designated Agency sub-head approved

their use for a compelling need.

When approved, Agencies must post clear notice of the nature of the

information collected in the cookies, the purpose and use of the information, whether

or not and to whom the information will be disclosed, and the privacy safeguards

applied to the information collected.

OMB Memo M-10-23 Memo Agencies should provide individuals with alternatives to third-party social media

websites and applications. Guidance for Agency Use of Third-Party

Websites and Applications When linking to third-party websites agencies must alert (e.g., via a pop-up)

visitors that they are being directed to a nongovernment websites that may have

different privacy policies.

If an agency embeds a third-party application on its website the agency's privacy

policy should disclose the third-party's involvement.

Agencies using third-party websites or applications should use appropriate

branding to distinguish the agency's activities from those of nongovernment actors.

If data is collected via a third-party website or application, the agency should

collect only the information necessary for the proper performance of agency func-

tions and which has practical utility.

OMB Circular A-130 and Paperwork

Reduction Act

Circular/Law Agencies are required to disseminate information to the public in a timely,

equitable, efcient, and appropriate manner.

Appendix A. Descriptions of selected policy instruments related to government use of social media

(continued on next page)

37 J.C. Bertot et al. / Government Information Quarterly 29 (2012) 3040

(continued)

Policy instrument Policy type Description

Agencies are required to establish and maintain Information Dissemination

Product Inventories.

Agencies must consider disparities of access and how those without internet

access will have access to important disseminations.

Agencies should develop alternative strategies to distribute information alongside

any utilization of social media tools.

When using electronic media the regulations that govern proper management

and archival of records still apply.

Agencies need to evaluate their use of Web 2.0 technologies and determine the

most appropriate methods to capture and retain records on both government servers

and technologies hosted on non-Federal hosts.

Section 8 of A-130:

Agencies are required to provide members of the public who do not have internet

connectivity with timely and equitable access to information, for example, by

providing hard copies of reports and forms.

Using social media technologies as an exclusive channel for information

distribution would prevent users without internet access, including economically

disadvantaged persons, from receiving such information.

Also, some social media technologies require high-speed internet access and band-

width, which may not be available in rural areas or may be unaffordable.

Rehabilitation Act of 1973 Law Section 504:

Creates broad standards of equal access to government activities and information

for individuals with disabilities, which includes content distributed via social media.

Establishes general rights to accessible information and communication

technologies, which includes social media tools.

Section 508:

Requires that electronic and information technologies purchased, maintained, or

used by the Federal Government meet certain accessibility standards.

These standards are designed to make online information and services fully

available to the 54 million Americans who have disabilities.

Agencies, as well as entities receiving federal funding, implementing social

media technology-based services must pay particular attention to complying with

the requirements of Section 508.

Agencies employing non-Federal services to provide social media technology

capabilities are also required to ensure that persons with disabilities have equivalent

access to the information on these third party sites as required in Section 508.

Executive Order 13166Improving

Access to Services for Persons

with Limited English Prociency

Executive Order Requires that agencies provide appropriate access to persons with limited English

prociency:

Encompasses all federally conducted programs and activities. Anything an

Agency does, including using social media technologies to communicate and

collaborate with members of the public, falls under the reach of the mandate.

Agencies must determine how much information they need to provide in other

languages based on an assessment of customer needs.

Social media technologies are not different than any other technology used by

the Federal government.

E-government Act of 2002 Law Agencies are required to develop priorities and schedules for making government

information available and accessible to the public.

Inventories must be posted on Agency websites.

The annual E-Government Act report to OMB must contain information on the

nal inventories, priorities, and schedules.

Compels agencies to comply with requirements of Section 508 of the

Rehabilitation Act in all online activities.

Agencies are required to implement and maintain an Information Dissemination

Management System.

Information Quality Act Law Agencies are required to maximize the quality, objectivity, utility, and integrity of

information and services provided to the public.

In terms of social media technologies, agencies must ensure reasonable suitable

information and service quality strategies consistent with the level of importance of

the information that include

Clearly identifying the limitations inherent in the information dissemination

product (e.g., possibility of errors, degree of reliability, and validity);

Taking reasonable steps to remove the limitations inherent in the information;

and

Reconsider delivery of the information or services.

Federal Information Security

Management Act (FISMA)

Law Requires a Certication and Accreditation (C&A) process for all Federal IT systems

that utilize social media technologies.

C&A activity must be performed by an independent third party auditing team

and must conform to the Risk Management Framework of the National Institute of

Standards and Technology.

Children's Online Privacy Protection

Act (COPPA)

Law Prohibits collection of individually identiable information from children.

Denes child as under the age of 13.

FTC determines if a website is directed to children.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act Law Requires equal access to all electronic materials used in public education.

Americans with Disabilities Act Law Created broad prohibitions on the exclusion of persons with disabilities from

government services and benets, including communication with the government.

Telecommunications Act of 1996 Law Promotes the development and implementation of accessible information and

communication technologies being used online.

Copyright/Intellectual Property

38 J.C. Bertot et al. / Government Information Quarterly 29 (2012) 3040

References

Barr, S. (2008). Agencies share information by taking a page from Wikipedia. Washington

Post, 28 January.

Benkler, Y. (2002). Coase's penguin, or Linux and the nature of the rm. Yale Law

Journal, 112(3), 369446.

Bertot, J. C., Jaeger, P. T., & Grimes, J. M. (2010). Crowd-sourcing transparency: ICTs,

social media, and government transparency initiatives. Proceedings of the 11th

Annual Digital Government Research Conference on Public Administration Online:

Challenges and Opportunities (pp. 5158).

Bertot, J. C., Jaeger, P. T., & Grimes, J. M. (2010). Using ICTs to create a culture of trans-

parency: E-government and social media as openness and anti-corruption tools for

societies. Government Information Quarterly, 27, 264271.

Bertot, J. C., Jaeger, P. T., & Grimes, J. M. (in press). Promoting transparency and account-

ably through ICTs, social media, and collaborative e-government. Transforming

Government: People, Process and Policy.

Bertot, J. C., Jaeger, P. T., Munson, S., & Glaisyer, T. (2010). Engaging the public in open

government: The policy and government application of social media technology

for government transparency. IEEE Computer, 43(11), 5359.

Bertot, J. C., Jaeger, P. T., Shuler, J. A., Simmons, S. N., & Grimes, J. M. (2009). Reconciling

government documents and e-government: Government information in policy,

librarianship, and education. Government Information Quarterly, 26, 433436.

Bimber, B. (2003). Information and American democracy: Technology in the evolution of

political power. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brabham, D. C. (2008). Crowdsourcing as a model for problem solving: An introduction

and cases. Convergence, 14(1), 7590.

Burnett, G., & Bonnici, L. (2003). Beyond the FAQ: Implicit and explicit norms in Usenet

newsgroups. Library and Information Science Research, 25, 333351.

Burnett, G., & Buerkle, H. (2004). Information exchange in virtual communities: A com-

parative study. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 9(2) Available:

http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol9/issue2/burnett.html.

Carlson, S. (2004). Left out online: Electronic media should be a boon for people with

disabilities, but few colleges embrace the many new technologies that could

help. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 50(40), A23.

Chang, A., & Kannan, P. K. (2008). Leveraging Web 2.0 in government. Washington DC:

IBM Center for The Business of Government.

Corbridge, S. (2007). The (im)possibility of development studies. Economy and Society,

36, 179211.

Dobransky, K., & Hargittai, E. (2006). The disability divide in internet access and use.

Information, Communication & Society, 9, 313334.

Drapeau, M., & Wells, L. (2009). Social software and national security: An initial net

assessment: Center for Technology and National Security Policy, National Defense

University Available:. http://www.ndu.edu/ctnsp/Def_Tech/DTP61.

Fox, S., & Livingston, G. (2007). Latinos online: Hispanics with lower levels of education

and English prociency remain largely disconnected from the internet. Washington,

DC: Pew Internet and American Life Project Available: http://www.pewinternet.

org.

General Services Administration. (2010). Social media handbook. Available: http://www.

gsa.gov/graphics/staffofces/socialmediahandbook.pdf.

Godwin, B. (2008). Matrix of Web 2.0 technology and government. USA.gov. Available:

http://www.usa.gov/webcontent/technology/other_tech.shtml.

Hansen, D. L. (2009). Overhearing the crowd: An empirical examination of conversa-

tion reuse in a technical support community. Proceedings of the fourth international

conference on Communities and technologies (C&T'09) (pp. 155164). New York,

NY: ACM.

Hansen, D. L., Shneiderman, B., & Smith, M. A. (2011). Analyzing social media networks

with NodeXL: Insights from a connected world. Burlington, MA: Morgan Kaufmann.

Hanson, E. C. (2008). The information revolution and world politics. Lanham, MD: Rowman

& Littleeld.

Harper, K. A., & DeWaters, J. (2008). A quest for website accessibility in higher educa-

tion institutions. Internet and Higher Education, 11, 160164.

Jaeger, P. T. (2011). Disability and the internet: Confronting a digital divide. Boulder, CO:

Lynne Reiner.

Jaeger, P. T., & Bertot, J. C. (2010). Designing, implementing, and evaluating user-

centered and citizen-centered e-government. International Journal of Electronic

Government Research, 6(2), 117.

Jaeger, P. T., & Bertot, J. C. (2011). Responsibility rolls down: Public libraries and the

social and policy obligations of ensuring access to e-government and government

information. Public Library Quarterly, 30, 125.

Jaeger, P. T., Bertot, J. C., & Shuler, J. A. (2010). The Federal Depository Library Program

(FDLP), academic libraries, and access to government information. Journal of

Academic of Librarianship, 36, 469478.

Jaeger, P. T., Lin, J., &Grimes, J. (2008). Cloud computing andinformationpolicy: Computing

in a policy cloud? Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 5(3), 269283.

Jaeger, P. T., Lin, J., Grimes, J. M., &Simmons, S. N. (2009). Whereis thecloud? Geography, eco-

nomics, environment, andjurisdictionincloudcomputing. First Monday, 14(5) Available:

http://www.uic.edu/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/2456/2171.

Jaeger, P. T., Paquette, S., & Simmons, S. N. (2010). Information policy in national political

campaigns: A comparison of the 2008 campaigns for President of the United States

and Prime Minister of Canada. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 7, 116.

Jaeger, P. T., & Thompson, K. M. (2003). E-government around the world: Lessons, chal-

lenges, and new directions. Government Information Quarterly, 20(4), 389394.

Jaeger, P. T., & Thompson, K. M. (2004). Social information behavior and the democratic

process: Information poverty, normative behavior, and electronic government in

the United States. Library and Information Science Research, 26(1), 94107.

Johnston, E. W., & Hansen, D. L. (in press). Design lessons for smart governance infra-

structures. In D. Ink, A. Balutis, & T. Buss (Eds.), American Governance 30 Rebooting

the Public Square. New York: M.E. Sharp.

Laris, M. (2009). O brave new world that has such avatars in it. Washington Post, 4

January Available: http://www.washingtonpost.com.

Lazar, J., & Jaeger, P. T. (2011). Reducing barriers to online access for people with dis-

abilities. Issues in Science and Technology, 17(2), 6882.

Lazar, J. L., & Wentz, B. (2011). This isn't your version: Separate but equal Web site

interfaces are inherently unequal for people with disabilities. User Experience, 10 (2).

Lenhart, A. (2010). Cell phones and American adults. Washington, DC: Pew Internet and

American Life Project Available: http://www.pewinternet.org.

Lessig, L. (2006). Code 2.0. New York: Basic.

Lipowicz, A. (2009). 4reasons why e-records are still a mess. Federal Computer Week, 6 March

Available: http://www.fcw.com/Articles/2009/03/09/policy-email-records.aspx.

Mackenzie, A. (2010). Wirelessness: Radical empiricism in network cultures. Cambridge,

MA: MIT Press.

Madden, M. (2010). Older adults and social media. Washington, DC: Pew Internet and

American Life Project Available: http://www.pewinternet.org.

Madison, J., Hamilton, A., & Jay, J. (1789). Federalist papers. In I. Kramnic (Ed.), New

York: Penguin.

Maloney-Krichmar, D., & Preece, J. (2005). A multilevel analysis of sociability, usability

and community dynamics in an online health community. Transactions on Human

Computer Interaction, 12(2), 132.

Miller, E. (2009). The Veterans Administration goes Web 2.0. The Sunlight Foundation

Blog. Available: http://blog.sunlightfoundation.com/taxonomy/term/Facebook/.

Noveck, B. E. (2008). Wiki-government. Democracy: A Journal of Ideas, Vol. 7.

Osimo, D. (2008). Web 2.0 in government: Why and how? Washington DC: Institute for

Prospective Technological Studies.

Paquette, S., Jaeger, P. T., & Wilson, S. C. (2010). Identifying the risks associated with

governmental use of cloud computing. Government Information Quarterly, 27,

245253.

Pirolli, P., Preece, J., & Shneiderman, B. (2010). Cyberinfrastructure for social action on

national priorities. Computer, 43(11), 2021.

Porter, J. (2008). Designing for the Social Web. Thousand Oaks, CA: New Riders Press.

Powell, A., Byrne, A., & Dailey, D. (2010). The essential internet: Digital exclusion in

low-income American communities. Policy & Internet, 2(2) (article 7).