Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Urban Stud 2013 Brambilla 3205 24

Caricato da

Nileena SankarankuttyDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Urban Stud 2013 Brambilla 3205 24

Caricato da

Nileena SankarankuttyCopyright:

Formati disponibili

http://usj.sagepub.

com/

Urban Studies

http://usj.sagepub.com/content/50/16/3205

The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1177/0042098013484539

2013 50: 3205 originally published online 16 May 2013 Urban Stud

Marco Brambilla, Alessandra Michelangeli and Eugenio Peluso

Equity in the City: On Measuring Urban (Ine)quality of Life

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Urban Studies Journal Foundation

can be found at: Urban Studies Additional services and information for

http://usj.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Email Alerts:

http://usj.sagepub.com/subscriptions Subscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Reprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Permissions:

What is This?

- May 16, 2013 OnlineFirst Version of Record

- Nov 15, 2013 Version of Record >>

at CEPT University on July 28, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from at CEPT University on July 28, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Equity in the City: On Measuring Urban

(Ine)quality of Life

Marco Brambilla, Alessandra Michelangeli and Eugenio Peluso

[Paper first received, August 2011; in final form, January 2013]

Abstract

In economic literature, the quality of life (QoL) in a city is usually assessed through

the standard revealed-preference approach, which defines a QoL index as the mone-

tary value of urban amenities. This paper proposes an innovative methodology to

measure urban QoL when equity concerns arise. The standard approach is extended

by introducing preferences for even accessibility to amenities throughout the city

into the QoL assessment. The QoL index is then reformulated to account for the

unequal availability of amenities across neighbourhoods. The more unbalanced the

distribution of amenities across neighbourhoods, the lower the assessment based on

the new index. This methodology is applied to derive a QoL index for the city of

Milan. The results show that the unequal distribution of amenities across neighbour-

hoods significantly affects the assessment of QoL for that city.

1. Introduction

The economic approach to measuring

urban quality of life (QoL) is based on the

work of Rosen (1979) and Roback (1982)

who, rather than assessing overall well-

being or happiness of households, measure

QoL indirectly, in terms of the monetary

value of local amenities. They define a QoL

index as the monetary value of a set of

amenities, where the amenities are location-

specific characteristics with positive or neg-

ative effects on individuals utility (Bartik

and Smith, 1987; Blomquist, 2006).

This paper focuses on a single city and

extends the previous methodology by pro-

viding a new measure to assess urban QoL

by explicitly taking into account equity

Marco Brambilla is in the DEFAP, Catholic University of Milan, Piazza Buonarroti 30, Milan,

20100, Italy. Email: mg.brambilla@polimi.it.

Alessandra Michelangeli (corresponding author) is in the Department of Economics, Management

and Statistics (DEMS), University of Milan-Bicocca, Piazza dellAteneo Nuovo 1, Building U6,

Milan, 20126, Italy. Email: alessandra.michelangeli@unimib.it.

Eugenio Peluso is in the Department of Economics, University of Verona, Vicolo Campofiore 4,

Verona, 37129, Italy. Email: eugenio.peluso@univr.it.

Urban Studies at 50

Article

50(16) 32053224, December 2013

0042-0980 Print/1360-063X Online

2013 Urban Studies Journal Limited

DOI: 10.1177/0042098013484539

at CEPT University on July 28, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

concerns. Our methodology relies on the

hypothesis that a more equal distribution

of resources in the city is beneficial to over-

all QoL. As we will see later, there are sev-

eral arguments for equity in the city, some

of them used as a starting-point for devel-

oping a branch of planning and economic

literature. Regardless of the perspective

adopted for studying the effect of equity on

QoL, or more generally well-being, every-

one agrees that the opposite of equityi.e.

inequalityis detrimental to quality of life.

The concentration of poor or disadvan-

taged people in some areas of the city can

generate negative externalities and fuel

social discontent, eventually leading to

slums, delinquency, drugs, and other symp-

toms of social and economic marginalisa-

tion (see Glaeser et al., 2008). In our

framework, the priority for equity is cap-

tured by the mathematical properties of an

explicit evaluation function. The specific

form of the evaluation function can embed

either citizens preferences for equity

(where useful, investigated by suitable sur-

veys) or the ethical judgment of a city plan-

ner. The main assumption is that an

unequal availability of amenities within the

city has a negative impact on the evaluation

function; in the same way as income

inequality generates a loss in social welfare

according to Atkinsons (1970) approach to

inequality measurement. Under this

assumption, a new QoL index is obtained

by discounting the Roback (1982) index

through a multiplicative correction term.

The more unbalanced the distribution of

amenities across neighbourhoods, the lower

the correction term. More precisely, the

correction term is obtained as the sum of

unidimensional inequality indices, account-

ing for the dispersion of each amenity

within the city, plus a residual term sum-

marising any correlation among the distri-

bution of amenities. This formulation can

be used to disentangle the contribution of

the dispersion of each amenity to the over-

all index from the joint effect of the ame-

nities. The correction term depends on as

many parameters as the number of ame-

nities under examination. Each parameter

registers the aversion to the unequal avail-

ability of the corresponding amenity within

the city. The model is therefore sufficiently

flexible to allow for a specific degree of

aversion to the unequal availability of each

amenity.

One point requires further explanation.

Our analysis is based on two different com-

ponents: the Roback (1982) spatial model

and an evaluation function expressing the

preferences for equity. In the former, the

representative agent looks for the most con-

venient location given the distribution of

amenities across neighbourhoods. The dif-

ferent amenities available at the equilibrium

are capitalised in housing prices and the

representative agents utility is equalised

within the city. This outcome is logically

independent of the fact that it might be

possible to increase or re-allocate some

amenities within the city, improving the

well-being of the representative citizen. This

effect is captured by the correction term

depending on the evaluation function. For

example, in the short run, agent location

decisions depend on the current availability

of green areas within the city, which also

affects his well-being at the equilibrium.

However, if new green areas are developed,

especially in neighbourhoods where they

are lacking, overall well-being in the city

increases. These points of view are recon-

ciled by first computing a Roback QoL

index based on the citizens evaluation of

amenities, then adjusted via the correction

term sensitive to their unequal availability.

The suggested methodology is illustrated

using data for the city of Milan over the

period 200408 regarding the availability of

education, green areas, recreational activi-

ties, commercial facilities, public transport

3206 MARCO BRAMBILLA ET AL.

at CEPT University on July 28, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

and socio-demographic characteristics. By

taking into account the uneven availability

of amenities within the city, the Roback

index is reduced by 28 per cent.

The methodology is shown in section 2.

Section 3 presents the empirical application

to Milan with a discussion of the data and

variables and a descriptive analysis of the

city neighbourhoods. The econometric spe-

cification of the hedonic function is also

discussed and the results are illustrated in

terms of amenity prices and QoL assess-

ment. Section 4 concludes and suggests

some potential extensions of our approach,

paving the way for future research.

2. Theoretical Framework

This section first reviews the Roback (1982)

index, then shows how to measure the avail-

ability of amenities within the city and,

thirdly, shows how to obtain a new QoL

index accounting for the unequal availabil-

ity of amenities across neighbourhoods.

2.1 The Roback (1982) QoL Index

Let a 2 <

k

+

be the vector of the average

quantities of k amenities in a given city.

The index developed by Rosen (1979) and

Roback (1982) consists of the weighted

sum of the values of the k amenities of the

city, where the weights are the implicit

prices associated with the amenities

QoL =

k

j =1

p

j

a

j

1

The implicit price p

j

for j = 1, ., k is esti-

mated through housing and wage hedonic

regressions. Actually the coefficients in the

estimated hedonic regression do not only

reflect consumer preferences, but also factors

that determine production. However, in the

case of a fixed supplied amenity, the hedonic

price reflects the preferences of the marginal

person just indifferent between buying a

house with and without amenity. For ame-

nities that vary more continuously through-

out a city, a hedonic regression is likely to

capture something much closer to mean pre-

ferences (Bayer and McMillan, 2008, p. 229).

The implicit price is the sum of the housing

price differential and the negative of the

wage differential. In other words, the eco-

nomic value of a local amenity is determined

by the housing price individuals are willing

to pay and the wage they are willing to accept

to locate in a given city. The idea underlying

this approach is that people will accept lower

wages and/or greater housing prices in an

area with desirable amenities, but require

greater wages and/or lower housing prices in

an area with less attractive amenities. As

Roback acknowledges

associating the implicit marginal price with

mean quantity of the amenity provides an

approximated value of the amenities because

the prices of infra-marginal units are differ-

ent from the marginal prices. Such an expen-

diture computation in (1) merely shows the

order of magnitude of the expenditure in the

average budget (Roback, 1982, p. 1274).

In what follows, the focus is on a single

city,

1

computing a QoL index for the whole

city that accounts for the uneven availabil-

ity of amenities across its neighbourhoods.

Focusing on a single city has three main

consequences.

First, the implicit prices of amenities in

(1) are derived solely from the hedonic

housing price equation. Wages are ignored

since they are assumed to be determined for

the citys labour market as a whole without

variation within the city. Actually, several

studies carried out on American cities show

that wages may vary slightly within a city.

According to Bartik and Eberts (2006), for

example, the wages of identical workers

EQUITY IN THE CITY 3207

at CEPT University on July 28, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

decline about 1 per cent for each additional

mile the job is located from the central busi-

ness district (CBD). Even supposing that

wages can vary within a city, it is not easy to

measure such a phenomenon, since the

neighbourhood where individuals live is not

necessarily where they work. In addition,

the lack of data on employment precludes a

consideration of city-wide wage variations.

Secondly, only the prices of amenities

that vary within the city can be identified.

We ignore several variables usually consid-

ered in intercity analysis (for example, cli-

mate, altitude).

A third potential problem with intracity

analysis relates to spatial sorting on unob-

servables (Gyourko et al., 1999). This occurs

when high-quality housing units are located

in the best city neighbourhoods and the fac-

tors determining the high quality of houses

are unobservable. The value of QoL will be

overestimated in the nice neighbourhoods.

This point will be returned to in section 4.

The conventional approach is now

extended to quantify the availability of

amenities for city inhabitants living in dif-

ferent neighbourhoods.

2.2 Amenities and Their Availability

Let us consider a city exogenously parti-

tioned into n neighbourhoods. Each neigh-

bourhood i =1, . . . , n is described by a

vector a

i

containing the values of the k ame-

nities. The element a

ij

2 <

+

indicates the

level of the amenity j in the neighbourhood

i. The information on the distribution of

amenities in the city is then summarised by

a n x k matrix, where each line corresponds

to a neighbourhood and each column to an

amenity

A=

a

11

. . .a

1k

a

n1

. . .a

nk

_

_

_

_

Suppose that an individual lives in a neigh-

bourhood with few amenities or none at all.

He can benefit from amenities located in the

surrounding neighbourhoods. Therefore,

the overall quantity of the amenities avail-

able is the sum of the amenities where the

individual dwells, plus a term indicating

their presence in the surroundings, whose

accessibility is a function of the distance

between the neighbourhood we are consid-

ering and its adjacent neighbourhoods (see

Figure 1).

In formal terms, starting from A, a fur-

ther n x k matrix Z is obtained, whose gen-

eric term z

ij

indicates the overall availability

of amenity j for individuals of neighbour-

hood i. The element z

ij

is obtained by adding

to a

ij

the availability of the amenity j in the

neighbourhoods bordering i. Defining S(i)

the set of neighbourhoods adjacent to i

(with i 2 S(i)), we obtain

z

ij

=

s2S(i)

a

is

f (d

is

) 2

where, a

sj

is the value of amenity j in the

neighbourhood s bordering i; f d

is

is the

value of a continuous and non increasing

function f : <

+

! 0, 1 defined on the dis-

tance d

is

between the neighbourhoods i and

s.

2

Let z

j

denote the average level of amenity

j in the city and z = z

1

, ::, z

k

the vector con-

taining the means of the k amenities in the

city. We reformulate the Roback (1982)

index as follows

il

d

Figure 1. Distance between district centroids.

3208 MARCO BRAMBILLA ET AL.

at CEPT University on July 28, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

QoL =

k

j =1

p

j

z

j

3

where, the vector of the average quantities a

is replaced by z.

We call this index the QoL index adjusted

for the available amenities. A procedure to

correct this index accounting for inequality

is now presented.

2.3 The Equity-adjusted QoL Index

The idea of just city is enshrined in both

planning and economic literature. The

equity approach developed in planning lit-

erature requires that urban amenities and

public services must be evenly available in a

way such that

everyone receives the same public benefit,

regardless of socioeconomic status, willing-

ness or ability to pay, or other criteria; resi-

dents receive either equal input or equal

benefit (Talen, 1998, p. 24).

An alternative approach (needs-based), fol-

lows a compensatory criterion that subor-

dinates the distribution of facilities and

services to the different needs of the popu-

lation living in different neighbourhoods of

the city.

3

In urban economics literature, aiming at

evenly available amenities within the city is

recommended by Berliant et al. (2006),

who determine the optimum number and

location of public facilities through a gen-

eral equilibrium analysis. They prove the

existence of an equilibrium characterised

by a dispersed and homogeneous distribu-

tion of public facilities across locations.

They also argue that an equal treatment

identical-provision optimum may be justi-

fied by the equal protection clause of the

US Constitution, federal law or by state

constitutions. On the efficiency side,

Benabou (1993) shows that stratification

can create ghettos and can even bring

about the complete collapse of the citys

productive capacity. Finally, from a social

welfare perspective, the equal availability of

local facilities mitigates well-being inequal-

ity (Aaberge et al., 2010) and promotes

equality of opportunities in the sense of

Roemer (1998) and van de Gaer (1993).

Moving from these different equity con-

cerns to an analysis of QoL, a measure of

QoL is now derived. This measure is able

to disentangle the different relevance, if

any, given to the unequal availability of

each amenity. For example, the unequal

availability of shopping facilities can have a

higher impact in lowering QoL than the

identically unequal availability of cultural

sites. Let W(Z) be the function evaluating

the distribution of the k amenities between

the n city neighbourhoods.

4

The function

W is assumed as additive

W(Z) =

1

n

n

i =1

w(z

i

) 4

where, w(z

i

) is the value taken by the

increasing and concave function

w : <

k

+

! < summarising the assessment

of the QoL in the neighbourhood i,

endowed with the vector of amenities z

i

.

It is well known (see Weymark, 2006)

that, under inequality aversion, the value

W(Z) is less than or equal to the value guar-

anteed by an even availability of the same

amount of amenities across neighbour-

hoods. If

~

W =W(Z)is the evaluation of the

current distribution, due to continuity, it is

possible to define a scalar q 2 0, 1 depend-

ing on Z and W, such that

~

W =W(Z) =

1

n

n

i =1

w(z

i

) =W(q z) 5

In the same spirit as Atkinson (1970), the

elements of the vector qz are called equally

distributed equivalent amenities (EDEAs).

EQUITY IN THE CITY 3209

at CEPT University on July 28, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

This equation (5) means that, if the propor-

tion q of the average amount of amenities is

uniformly available across neighbourhoods,

the evaluation function W(q z) reaches the

same value W(Z) associated with the actual

distribution.

Accounting for inequality, the index

adjusted for the available amenities (3) is

then modified as follows

Definition 1. For any Z, the equity-adjusted

urban quality of life index QoL

q

(Z; W) is

QoL

q

(Z; W) =q

k

j =1

p

j

z

j

6

where, p

j

is the implicit price of the amenity j

and the equally-distributed equivalent ame-

nities vector qz is implicitly defined by (5).

Instead of assessing the value of z repre-

senting the average quantity of amenities

available in the city as in (3), the equity-

adjusted QoL index (6) corrects it through

a multiplicative factor q. The vector qz

consists in the multidimensional extension

(Tsui, 1995; Weymark, 2006) of the equally

distributed equivalent income used in

inequality literature (Atkinson, 1970) and

of the certainty equivalent used in risk

theory (Pratt, 1964). The more unbalanced

the distribution of amenities, the lower the

correction term q. In the Appendix, we

show how to derive q from the evaluation

function (5). The proposed methodology

can be used to disentangle the contribution

of each amenity to the value of q and then

to the overall QoL index. The correction

term q is derived through a parametric

inequality index embedding preferences for

an equal availability of the k amenities

within the city. The k parameters measure

the level of inequality aversion of either citi-

zens or a city planner on each dimension.

Identifying the origin of the aversion to

inequality is beyond the aim of this paper.

Our aim is to show how preferences for

equity can be introduced in QoL assess-

ment, without recommending a specific

equity perspective. In this respect, our

attempt offers a pioneering contribution to

both urban and inequality literature.

5

To

proceed with the empirical investigation, a

pragmatic procedure is adopted to calibrate

inequality aversion, exploiting the available

information on the willingness to pay for

each amenity, estimated through a hedonic

model referred to the housing market. The

k parameters indicating aversion to the

unequal availability of the different ame-

nities will be set equal to their respective

weight on the citys monetary assessment of

quality of life.

3. Empirical Application

In this section, we employ the previous

model to assess QoL in Milan, the largest

city in Italy after Rome.

6

In addition to

being the biggest industrial city in Italy, it is

also a historical city with a significant assort-

ment of churches, buildings and monu-

ments mainly inside the Mura Spagnole, the

city walls that border the historical city

centre. Despite all these positive aspects,

other factors do not positively impact on

quality of life. Some neighbourhoods have

experienced a gradual process of urban

decay and more and more Italian residents

have abandoned these areas. Housing prices

have decreased and these neighbourhoods

have frequently attracted newcomers to

Milan. The next section describes the infor-

mation we have collected to capture these

phenomena and, more generally, the main

variables affecting the quality of life in the

different neighbourhoods of Milan.

3.1 Data and Variables

As we showed in relation to the Roback

(1982) QoL index in (1), overall QoL

3210 MARCO BRAMBILLA ET AL.

at CEPT University on July 28, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

depends on the set of amenities considered

when implementing the analysis. For the

purpose of this study, several data sources

are combined into a single dataset that con-

tains detailed information on housing and

city characteristics. Data on residential

housing transactions were taken from the

Osservatorio del Mercato Immobiliare

(OMI) managed by a public agency (the

Agenzia del Territorio). Transactions refer

to 55 neighbourhoods identified by the

OMI for a period of 5 years, from January

2004 to December 2008.

7

Each neighbour-

hood is internally homogeneous in terms of

socioeconomic and urban characteristics,

making it likely that prices of houses located

within a neighbourhood move together. In

addition to the housing market value, the

dataset provides a detailed description of

structural attributes, such as total floor

space, age of the building in the year of sale,

number of bathrooms, whether the housing

unit needs to be renovated, whether the

housing unit has independent heating, the

floor above street level, presence of an eleva-

tor or a garage, and build quality.

Neighborhood-level data on amenities

and socioeconomic conditions were taken

from public authority records. They include

information on six important aspects of

quality of life: environmental characteris-

tics, public transport, education, shopping

facilities, recreational activities, and socioe-

conomic characteristics. Table A2 in the

Appendix sets out a full list of variables

used in our analysis with their sources. Of

course, other variables that cannot be so

readily observed may contribute to the

quality of life as presented in this paper. In

addition, depending on the revealed prefer-

ences of residents over a limited bundle of

amenities, our QoL index could not prop-

erly account for the preferences of those res-

idents who give priority to other (omitted)

amenities. However, this paper aims to

show the potential of our methodology,

carrying out an empirical analysis which is

as rigorous as possible.

The environmental dimension is proxied

by the green areas relative to the area of the

neighbourhood (Green); public transport is

represented by the number of metro stations

(Transport); shopping facilities (Shopping

facilities) are proxied by the number of

supermarkets, discount stores and malls per

10 000 inhabitants; the recreational dimen-

sion (Cultural) is proxied by the number of

cinemas, theatres, museums, art galleries,

academies of music and libraries per 10 000

inhabitants.

The socioeconomic dimension (Ethnic)

is based on the ratio of Italian/foreign resi-

dents. More precisely, the Ethnic variable

for the neighbourhood i is constructed as

Ethnic

i

=

It

i

s2S(i)

Imm

s

~

d

2

is

where, It

i

is the number of Italians living in

the neighbourhood i. In the denominator,

we add to the immigrants living in the

neighbourhood, Imm

i

, those living in the

surrounding neighbourhoods. The weight

associated with immigrants of each adjacent

neighbourhood s 2 S(i) is set to be equal to

1

~

d

2

is

, with

~

d

2

is

=max(1, d

is

) and roughly approx-

imates the probability that Italian residents

in neighbourhood i interact with foreigners

in neighbourhood s. In this case, our

assumption of preference for equity corre-

sponds to aversion to residential segregation.

The resulting unidimensional index for the

variable Ethnic can be safely interpreted in

terms of a segregation index of the exposure

class (see Reardon and OSullivan, 2004). In

this spirit, we consider as foreign residents

(Imm) the ethnic groups most often subject

to discrimination, such as African, South

American and some Asian communities.

Other immigrantsfrom, for example,

North America or western Europehave

EQUITY IN THE CITY 3211

at CEPT University on July 28, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

become invisible in Italy

8

and are included

with Italian residents.

Education is proxied by the proximity to

the nearest university (Proximity_University).

Unfortunately, we do not have information

on other variables for the quality of educa-

tion, such as the percentage of pupils moving

up to a higher class or parameters for class-

room and/or building facilities.

9

We do have

information on the degree of availability of

different educational levels, such as the

number of primary and secondary schools,

both public and private, in the neighbour-

hood. We also have data on early years of

educationi.e. the number of nursery

schools and pre-schools. We tried alternative

specifications including these variables but

none of these turned out to be statistically

significant. There are at least two reasons for

this result. First, the number of schools avail-

able in the neighbourhood is a rough proxy

of education services and is unable to capture

the quality of education services. Secondly,

the variability of some of these covariates is

quite modest across neighbourhoods.

In addition to these amenities, the

Euclidean proximity of each neighbour-

hood to the city centre is included, in order

to handle the problem of the spatial sorting

on unobservables described in section 2.1.

Furthermore, the Euclidean proximity to

the city centre enables verification of the

hypothesis of a monocentric structure of

the urban area modelled by Alonso (1965)

and Muth (1969). The urban pattern of

Milan is clearly identifiable by the old inner

ring of inland waterways (Navigli) designed

by Leonardo da Vinci. Outside the former,

a second ring comprises the Mura Spagnole.

The most important historical monuments

(Duomo, Castello Sforzesco, Royal Palace,

etc.) and historical buildings of residential

use are located within the two rings, beyond

which, as far as the confines of the munici-

pal territory, large neighbourhoods spread

out.

10

Descriptive statistics are set out in Table 1.

Amenity statistics enshrine the availability of

amenities in the bordering zones, calculated

by using the distance function f d

is

=

1

~

d

2

is

.

Following Marans (2003), the distance is

expressed in miles: amenities located in sur-

rounding neighbourhoods at a distance less

than or equal to a mile are added to that of

the initial neighbourhood entirely, while

those further than a mile are divided by d

2

is

.

The specification of f can be motivated in

this case by the current practice adopted in

gravitation models (White, 1983; Batten and

Boyce, 1986; Wong, 1993).

The average value of the 2592 properties

sold over the 200408 period was e403 288.

The average property had 95.72 square

metres of total floor space and was 48 years

old at the time of sale. Each neighbourhood

had on average 12 per cent of greenery in the

urban area, but with substantial differences

from 1 per cent in the Ronchetto Chiaravalle

Ripamonti neighbourhood in the south-west

to 25 per cent in the off-centre neighbour-

hood of Monza Precotto Gorla in the north.

The number of metro stations also varies

greatly: from 0 to 13 stations. Each neigh-

bourhood had on average 9.44 shopping

areas and five cultural sites per 10 000 inha-

bitants. Finally, the average ratio of foreign to

Italian residents in the neighbourhood was 9

per cent, the minimum percentage being 3.22

and the maximum 21.26.

3.2 Estimated Implicit Prices

To obtain the full implicit prices of location-

specific amenities given in (6), we estimate a

reduced form of the housing price hedonic

equation

ln p

hit

=b

0

+b

1

X

hit

+b

2

A

it

+h

hit

7

where, ln p

hit

is the price of housing unit h in

neighbourhood i at time t; X

hit

is a vector of

housing characteristics; A

it

is a vector of

3212 MARCO BRAMBILLA ET AL.

at CEPT University on July 28, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

available amenities in neighbourhood i; h

hit

~

N(0, s

2

n

):The structural characteristics in X

hit

are listed in Table A2. In addition to these

characteristics, the proximity of each neigh-

bourhood to the city centre and year dummies

are included in X

hit

to account for unobserva-

ble factors and time fixed effects respectively.

3.3 Results

Table 2 presents the results obtained from

estimating (7) by OLS. Robust standard

errors are used with clustering at neighbour-

hood level in order to allow for within-

neighborhood correlation. All in all, the

housing variables used in the model account

for about 87 per cent of the variance of the

logarithm of price. The stability of the

regression model was verified using pairwise

Chow tests on adjacent sub-periods. The

hypothesis of no structural change is not

rejected with the exception of the sub-

period 200607. Therefore our model

appears to be sufficiently stable. The amenity

Table 1. Summary statistics for the variables

Variable Mean S.D. Minimum Maximum Unit

Housing value 403 288 409 900 80 000 7 000 000 Euro

Market_p 0.304 0.460 0 1 Dummy

Offer_p 0.446 0.496 0 1 Dummy

Estimated_p 0.251 0.434 0 1 Dummy

Amenities

Transports 4.36 3.31 0 12.90 Continuous

Proximity_university 4.61 1.62 0 6.60 Km

Green 12.04 5.24 1 25 Percentage

Cultural 5.00 10.74 0.06 70.43 Continuous

Shopping_facilities 9.44 4.96 1.34 21.64 Continuous

Ethnic 9.14 3.75 3.22 21.26 Percentage

Housing characteristics

Total floor area 95.72 46.01 19.00 452 Square metres

Number of bathrooms 1.36 0.63 1 6 Discrete

To be renovated 0.042 0.200 0 1 Dummy

Heating 0.124 0.330 0 1 Dummy

2nd floor (or higher) 0.817 0.386 0 1 Dummy

Low_cost 0.538 0.498 0 1 Dummy

Medium_cost 0.428 0.494 0 1 Dummy

Luxury 0.032 0.178 0 1 Dummy

Parking 0.019 0.067 0 1 Dummy

Elevator 0.819 0.384 0 1 Dummy

Age 48.20 21.90 1 205 Discrete

Control variables

City centre 0.15 0.35 0 1 Dummy

Proximity_city centre 4.50 2.20 0.1 9.3 Km

Year 2004 (ref.) 0.14 0.35 0 1 Dummy

Year 2005 0.23 0.42 0 1 Dummy

Year 2006 0.19 0.39 0 1 Dummy

Year 2007 0.21 0.41 0 1 Dummy

Year 2008 0.20 0.40 0 1 Dummy

EQUITY IN THE CITY 3213

at CEPT University on July 28, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

coefficients are statistically significant; to

quantify their relative importance in our

specification, standardised beta coefficients

are set out in column 3.

11

According to this

criterion, the most important amenity is

Green since an increase by one standard

deviation in this variable implies an increase

of 0.161 standard deviation in the value of

the housing unit. One possible explanation

of the statistical relevance of this variable is

that it measures not only the size of the avail-

able green areas, but also the facilities which

are often located within gardens and parks

(playgrounds for children, bicycle lanes and

sports centres). The next amenity in terms of

importance is Cultural (0.156). In this case,

Table 2. Hedonic regression

Variable Coefficient t Standard b coefficient

Intercept 10.600 273.90

Offer_p 0.062 4.51 0.048

Estimated_p 0.007 0.51 0.005

Amenities

Transport 0.007 4.21 0.041

Proximity_university 0.004 1.05 0.011

Green 0.001 2.02 0.161

Cultural 0.009 11.72 0.155

Shopping_facilities 0.003 2.31 0.025

Ethnic 0.008 5.84 0.048

Housing chacteristics

ln(size) 0.940 67.07 0.662

Second bathroom 0.048 3.65 0.035

Third bathroom 0.093 3.49 0.027

To be renewed 0.110 4.85 0.035

Heating 0.012 0.86 0.006

2nf floor (or higher) 0.017 1.53 0.010

Medium cost 0.029 2.73 0.023

Luxury 0.116 4.21 0.032

Parking 0.154 3.33 0.023

Elevator 0.068 5.41 0.041

ln(age) 0.006 1.51 0.018

proximity 0.0003 3.48 0.123

proximity squared 0.0001 1.83 0.077

Control variables

City centre 0.104 4.16 0.059

Year 2005 0.040 2.72 0.027

Year 2006 0.108 7.08 0.068

Year 2007 0.101 6.09 0.663

Year 2008 0.104 6.03 0.067

Number of observations 2592

F(26; 2565) 672.8400

Prob . F 0.0000

R

2

0.8721

Adjusted R

2

0.8708

3214 MARCO BRAMBILLA ET AL.

at CEPT University on July 28, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

the importance could be explained by the

location of specific theatres and museums in

ancient buildings where individuals appreci-

ate aesthetic and artistic value. For example,

the Museum of Ancient Art is in the Castello

Sforzesco, probably the most famous build-

ing in Milan, together with the Duomo and

La Scala Opera House. The other standar-

dised beta coefficients are 0.048 for Ethnic,

0.042 for Transport, 0.025 for Shopping facil-

ities and 0.011 for the proximity to the near-

est university (Proximity_university).

Full implicit prices for each amenity are

shown in Table 3, with Cultural, Ethnic and

Transport showing the highest prices in

absolute value. The hedonic price for an

additional cultural site per 10 000 inhabi-

tants in the areal unit is e2839; increasing

the Italian/foreign ratio by one leads to an

increase of e2500 in the value of the aver-

age housing unit and an additional metro

station provides a benefit of e2470. We

included distance from the nearest univer-

sity and it turns out that reducing the dis-

tance by 1 km increases housing unit value

by e1377. The estimated implicit price for

an additional shopping facility per 10 000

inhabitants is e1051 and the hedonic price

for public green areas is e 612 for one more

percentage point.

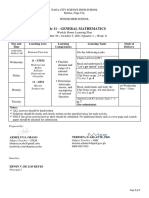

Column 2 in Table 3 sets out the values of

e, given by (A6), which corresponds to the

contribution of each amenity to the determi-

nation of the overall QoL index adjusted by

the availability of the amenities defined by

equation (3). These values are represented in

the pie chart in Figure 2 where it is evident

that variables related to social dimension

(Ethnic) and leisure (Cultural) play the most

important role.

According to the model presented in sec-

tion 3 and detailed in the Appendix, the

weights s= s

1

, ::, s

k

assigned to the set

of amenities are calculated using the esti-

mated implicit prices and the average quan-

tities of amenities in the city according to

equations (A5) and (A6). The third column

in Table 3 shows that these weights are

fairly similar and that the lowest is assigned

to the socioeconomic amenity Ethnic. This

implies that aversion to the unequal distri-

bution of immigrants across neighbour-

hoods will be higher than to the unequal

distribution of the other amenities.

The last column in Table 3 shows the

values of the equally distributed equivalent

share g

j

associated with each amenity j. As

stated earlier, it corresponds to the share of

the city-wide average value of the amenity j

so that, if equally distributed throughout all

Table 3. Hedonic prices and QoL indexes

Variable p

j

(e) e

j

=

p

j

z

j

k

l =1

p

l

z

l

[A6] s

j

=

1e

j

k1

[A5] l

j

=

1

z

j

1

n

n

i =1

z

s

j

ij

_ _1

s

j

[A2]

Transport (e/station) 2 475 0.151 0.1698 0.5418

Prox_univ (e/km) 1 377 0.089 0.1822 0.8608

Green (e/ +1%) 612 0.103 0.1794 0.5683

Cultural (e/unit) 2 839 0.198 0.1603 0.3339

Shop_fac (e/unit) 1 051 0.139 0.1722 0.8671

Ethnic (e/unit) 2 500 0.320 0.1360 0.9300

QoL index (equation (3)) 71 473

Correlation term k 1.0909

Correction term u 0.72

Equity-adjusted index QoL

u

51 460

EQUITY IN THE CITY 3215

at CEPT University on July 28, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

neighbourhoods, it would provide the same

value of the evaluation function (4) assessed

with the actual distribution of j, as claimed

by equation (5). Its value depends both on

the degree of aversion to the unequal distri-

bution of amenity j and its actual distribu-

tion across neighbourhoods. The highest

value of g

j

is for Ethnic (0.93), which shows

a limited degree of residential segregation

in Milan, followed by Shopping facilities

(0.86) and Proximity to university (0.86).

The lower g

j

found for Cultural (0.33)

Transport (0.54) and Green (0.56) roughly

indicate an unequal availability of these

amenities across city neighbourhoods.

Finally, the interaction term k is calculated

to be slightly bigger than 1 (1.09),

12

imply-

ing that the joint effect of amenity distribu-

tions positively contributes to the overall

equity-adjusted QoL index.

The last step backward defines the extent

of the reduction of the QoL index adjusted

for the amenity availability shown in (3).

This value amounts to e71 473. The calcu-

lations carried out show that the overall

correction term q amounts to 0.72 and

therefore the QoL index accounting for

equity is equal to e51 460. This result does

not differ so much from the benchmark

case where e

j

is 1/6 for all j and inequality

aversion is the same for each amenity. The

correction term q reduces from 0.28 to

0.26 and the adjusted QoL value rises to

e52 246.

3.4 Discussion

This result implies that the uneven availabil-

ity of amenities within the city reduces the

index adjusted for the availability of ame-

nities (3) by 28 per cent. Increasing the level

of amenities improves quality of life but

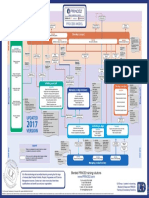

their even availability also matters. Figure 3

shows the level of QoL by neighbourhood

computed according to (3).

13

This map

confirms the monocentric shape of Milan

where QoL levels are much higher in the

city centre and decrease as the distance from

the centre increases. All neighbourhoods in

the city centre have a QoL value near to or

far exceeding e100 000, with the exception

of neighbourhood 6Castello, Melzi dEril,

Sarpi with a value of e74 775. This lower

value is due to the numerous settlement in

the past 10 years of wholesalers trading in

clothing and leather goods, essentially com-

prising a Chinese community. Moreover, in

the district there is friction between resi-

dents and wholesalers because of the

Figure 2. Contribution of amenities to the overall QoL index adjusted for the availability of

amenities.

3216 MARCO BRAMBILLA ET AL.

at CEPT University on July 28, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

continuous loading and unloading of

goods, causing traffic problems and endan-

gering pedestrians. The lowest value

(e30 096) is for neighbourhood 55

Quarto Oggiaro, Roserio, Amorettiwhich

sprang up in the 1950s to house workers

from southern Italy. In the course of time,

this neighbourhood developed a reputation

for organised crime, dilapidated housing

and a high percentage of illegal immigrants

(of the 4000 apartments made available by

public housing, 700 are occupied illegally).

The relationship between the value of

QoL and income across neighbourhoods is

examined. The Pearson correlation coeffi-

cient is 0.846 implying that QoL is strongly

positively related to income. This result is in

line with the study of Brueckner et al. (1999)

regarding the importance of amenities in

driving the location choice of rich individu-

als towards the best-endowed neighbour-

hoods, rises rapidly with income.

We conclude this section with a concern

about whether these empirical results would

still be meaningful if the needs-based criter-

ion of equity in the city, cited in section 2.3,

was adopted. Suppose for instance that

households comprising people of over 65

years of age are concentrated in a few city

neighbourhoods. In this case, it would be

reasonable to concentrate amenities such as

healthcare services in these neighbour-

hoods. To investigate this point, we looked

at the distribution of two kinds of house-

holds with specific traits able to shape their

preferences (households with children and

people over 65) in Milan. It turns out that

these households are evenly distributed

across city neighbourhoods (their Gini con-

centration index is respectively 0.056 and

0.068) so we can conclude that our results

hold up against the preference heterogeneity

induced by the demographic composition

of households.

0 - 40 000

40 000 - 75 000

> 75 000

52

48

49

46

47

50

51

53

23

25

55

26

24

27

30

28

29

32

31

33

35

34

21

20

36

37 38

19

39

40

42

41

54

43

44

45

18

17

16

10

9

15

13

5

14

12

11

22

6 7

4

3

2

1

8

1 km

Figure 3. QoL across Milan neighbourhoods. Key: see Table A1 for key to names of

neighbourhoods.

EQUITY IN THE CITY 3217

at CEPT University on July 28, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

4. Concluding Remarks

This paper is an original attempt to bridge

the gap between the urban economics and

inequality measurement literature. Starting

from the premise that these two fields of

economics share a multidimensional view

of QoL, we propose an innovative metho-

dology to assess urban QoL when equity

concerns arise. Without recommending any

specific equity perspective, we show how

preferences for equity can be introduced

into QoL assessment through a simple list

of parameters which generate a correction

term for the Roback QoL index adjusted

for amenity availability. Our empirical

investigation for Milan indicates the quite

significant impact of inequality on the QoL

index for the whole city. To disentangle

this result, we assessed QoL across neigh-

bourhoods, showing significant differences.

Milan has a monocentric shape like other

major European cities both in terms of

income and QoL values. These two vari-

ables are strongly positively related across

Milans neighbourhoods. Better-endowed

districts attract wealthier households. It fol-

lows that to decrease stratification in the

city, improving efficiency and equalising

opportunities and life-chances in the spirit

of Massey and Denton (1996), policies

favouring a more even availability of ame-

nities should be promoted. In this perspec-

tive, our methodology has a wide range of

applications, from simulating the effects of

changes in the provision of public goods on

QoL, to the analysis of poverty and stratifi-

cation at the urban level. It can also be

used to assess the effects of gentrification

(Helms, 2003; Lees, 2008) or urban renova-

tion policies (Barthelemy et al., 2007).

Finally, our approach could be extended on

the basis that certain groups might be

better clustered for equity reasons (i.e. the

elderly or families with children). In this

case, the correction term applied to the

QoL indicator should account for the

degree of association between the distribu-

tion of these categories of people and the

spatial provision of specific amenities. This

constitutes a promising avenue for future

research.

Notes

1. A large number of studies have used data

for a single city focusing in particular on

environmental issues (air or water pollu-

tion, proximity to noxious sites, etc.). See,

for example, Kohlhase (1991); Michaels and

Smith (1990).

2. In our application, for the sake of simpli-

city, we use the Euclidean distance between

the centroids of the neighbourhoods. Of

course a more refined technique would be

to use commuting time and mobility costs,

where these data are available.

3. At the end of the empirical section, we

show that the results for Milan also prove

to be robust in the light of this second per-

spective. See Lucy (1981) for a taxonomy of

equity criteria in urban planning and Rusk

(2003) for a long-term analysis of US cities.

4. To simplify the presentation, in what fol-

lows we simply call amenities the ame-

nities adjusted for their availability.

5. Indeed, in the body of literature on

inequality and welfare measurement, the

traditional approach based on the prefer-

ences of a social planner has only recently

been questioned by alternative approaches

based on individual preferences (see

Fleurbaey and Maniquet, 2011).

6. The total population was 1 295 339 inhabi-

tants in 2008, within an area of about 183

square km.

7. See Table A1 in the Appendix for the list of

districts with their population size.

8. As in other Western countries; see for

example Pan Ke Shon (2010) for France.

9. By classroom facilities we mean, for exam-

ple, modern teaching aids, air conditioned

rooms, spacious rooms and neat and clean

classrooms. The building facilities are, for

example, recreation and gym facilities,

3218 MARCO BRAMBILLA ET AL.

at CEPT University on July 28, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

high-speed Internet access, an extensive

library and computer lab facilities.

10. Michelangeli and Zanardi (2009) provide

empirical evidence for a monocentric shape

of the residential housing market in Milan.

Gonzales (2009, sec. 3) describes the histor-

ical and political roots of the monocentric

structure of Milan. More recently Veneri

(2013) accounts for the transformation into

an increasingly polycentric space of the

Milan metropolitan area. Extending our

analysis to such a larger area would require

an alternative empirical specification of the

hedonic equation (7).

11. The standardised beta coefficient quantifies

how many standard deviations change the

value of a house when each control variable

is increased by one standard deviation.

12. If k were equal to 1 there would be no joint

effect of amenity distributions on QoL index.

13. To compute the QoL index adjusted for the

available amenities for neighbourhood i,

with i = 1, ., n, equation (3) is modified

as follows

QoL

i

=

k

j =1

p

j

z

ij

14. We do not explore these properties and

invite the reader interested in axiomatics to

consult Tsui (1995).

15. The reader will note that 1 l

j

is exactly

the famous Atkinson (1970) inequality

index: so l

j

approaches 1 when the amenity

j is evenly available within the city; while l

j

approaches 0 when inhabitants of only few

neighbourhoods are neatly advantaged.

16. See also Brambilla and Peluso (2010).

17. This issue is usually solved in multidimen-

sional inequality literature by resorting to

sensitivity analysisi.e. by showing how the

results stand up to different numeric values

for the parameters.

18. See www.lisdatacentre.org/data-access/key-

figures/download-key-figures/.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the Osservatorio del

Mercato Immobiliare for data on housing trans-

actions; the Statistics Bureau of the Municipality

of Milan joint with the Department of Statistics

of the University of Milano-Bicocca for data on

income and demographic variables; Luca Stanca

for data on public transportation. We would like

to thank the editors for their time and valuable

remarks. We thank also Rolf Aaberge, Francesco

Andreoli, Michel Le Breton and Vito Peragine for

useful discussions. The usual disclaimer applies.

Funding

Financial support by the Italian Ministry of

University and Research and the Institute for

Economic Research on Firms in Vicenza is grate-

fully acknowledged.

References

Aaberge, A., Bhullera, M., Langrgena, A. and

Mogstad, M. (2010) The distributional

impact of public services when needs differ,

Journal of Public Economics, 94, pp. 549562.

Abul Naga, R. H. and Geoffard, P.-Y. (2006)

Decomposition of bivariate inequality by

attributes, Economic Letters, 90, pp. 362367.

Alonso, W. (1965) Location and Land Use:

Toward a General Theory of Land Rent. Cam-

bridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Atkinson, A. (1970) On the measurement of

inequality, Journal of Economic Theory, 3, pp.

244263.

Barthelemy, F., Michelangeli, A. and Trannoy, A.

(2007) La renovation de la Goutte dOr est-

elle un succe`s? Un diagnostic a` laide dindices

de prix immobilier, Economie et prevision,

180/181, pp. 107126.

Bartik, T. J. and Eberts, W. R. (2006) Urban labor

markets, in: R. J. Arnott and D. P. McMillen

(Eds) A Companion to Urban Economics, pp.

389403. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Bartik, T. J. and Smith, V. K. (1987) Urban ame-

nities and public policy, in: E. S. Mills (Ed.)

Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics,

Vol. II, pp. 12071254. Amsterdam: North-

Holland.

Batten, D. F. and Boyce, D. E. (1986) Spatial

interaction, transportation and interregional

commodity flow models, in P. Nijkamp (Ed.)

Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics,

EQUITY IN THE CITY 3219

at CEPT University on July 28, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Vol. I, pp. 357406. Amsterdam: North-

Holland.

Bayer, P. and McMillan, R. (2008) Distinguish-

ing racial preferences in the housing market:

theory and evidence, in: A. Baranzini, J.

Ramirez, C. Schaerer and P. Thalmann (Eds)

Hedonic Methods in Housing Markets: Pricing

Environmental Amenities and Segregation, pp.

225244. Geneva: Springer.

Benabou, R. (1993) Working of a city: location,

education, and production, Quarterly Journal

of Economics, 108, pp. 619652.

Berliant, M., Peng, S.-K. and Wang, P. (2006)

Welfare analysis of the number and locations

of local public facilities, Regional Science and

Urban Economics, 36, pp. 207226.

Blomquist, G. C. (2006) Measuring quality of

life, in: R. J. Arnott and D. P. McMillen (Eds)

A Companion to Urban Economics, pp. 479

482. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Brambilla, M. G. and Peluso, E. (2010) A

remark on decomposition of bivariate

inequality indices by attributes by Abul

Naga and Geoffard, Economics Letters, 108,

pp. 493507.

Brueckner, J., Thisse, J.-F. and Zenou, Y. (1999)

Why is central Paris rich and downtown

Detroit poor?, European Economic Review,

43, pp. 91107.

Fleurbaey, M. and Maniquet, F. (2011) A Theory

of Fairness and Social Welfare. New York:

Cambridge University Press.

Gaer, D. van de (1993) Equality of opportunity

and investment in human capital. PhD thesis

Leuven University.

Glaeser, E. L., Resseger, M. G. and Tobio, K.

(2008) Urban inequality. Working Paper No.

14419, NBER, Cambridge, MA.

Gonzales, S. (2009) (Dis)connecting Milan(ese):

deterritorialised urbanism and disempower-

ing politics in globalizing cities, Environment

and Planning A, 41, pp. 3147.

Gyourko, J., Kahn, M. and Tracy, J. (1999) Qual-

ity of life and environmental comparisons, in:

P. C. Cheshire and E. S. Mills (Eds) Handbook

of Regional and Urban Economics, Vol. 3, pp.

14131454. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Helms, A. C. (2003) Understanding gentrifi-

cation: an empirical analysis of the deter-

minants of urban housing renovation,

Journal of Urban Economics, 54, pp. 474

498.

Kohlhase, J. E. (1991) The impact of toxic waste

sites on housing values, Journal of Urban Eco-

nomics, 30(1), pp. 126.

Lees, L. (2008) Gentrification and social mixing:

towards an inclusive urban renaissance?,

Urban Studies, 45(12), pp. 24492470.

Lucy, W. (1981) Equity and planning for local

services, Journal of the American Planning

Association, 47(4), pp. 447457.

Marans, R. W. (2003) Understanding environ-

mental quality though quality of life studies:

the 2001 DAS and its use of subjective and

objective indicators, Landscape and Urban

Planning, 65, pp. 7383.

Massey, D. and Denton, N. (1996) American Apart-

heid: Segregation and the Making of the Under-

class. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Michaels, R. and Smith, V. K. (1990) Market

segmentation and valuing amenities with hedo-

nic methods: the case of hazardous waste sites,

Journal of Urban Economics, 28, pp. 223242.

Michelangeli, A. and Zanardi, A. (2009) Hedo-

nic-based price indexes for the housing

market in Italian cities: theory and estima-

tion, Politica Economica, 2, pp. 109146.

Muth, R. F. (1969) Cities and Housing. Chicago,

IL: Chicago University Press.

Pan Ke Shon, J.-L. (2010) The ambivalent nature

of ethnic segregation in Frances disadvan-

taged neighbourhoods, Urban Studies, 47(8),

pp. 121.

Pratt, J. W. (1964) Risk aversion in the small and

in the large, Econometrica, 32, pp. 122136.

Reardon, S. F. and OSullivan, D. (2004) Mea-

sures of spatial segregation, Sociological Meth-

odology, 34, pp. 121132.

Roback, J. (1982) Wages, rents, and the quality

of life, Journal of Political Economy, 90, pp.

12571278.

Roemer, J. (1998) Equality of Opportunity.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rosen, S. (1979) Wages-based indexes of urban

quality of life, in: P. M. Mieszhowski and M.

R. Straszheim (Eds) Current Issues in Urban

Economics, pp. 74104. Baltomore, MD:

Johns Hopkins University Press.

Rusk, D. (2003) Cities without Suburbs: A Census

2000 Update. Washington, DC: Woodrow

Wilson Center Press.

Talen, E. (1998) Visualizing fairness, Journal of

the American Planning Association, 64(1), pp.

2238.

3220 MARCO BRAMBILLA ET AL.

at CEPT University on July 28, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Tsui, K.-Y. (1995) Multidimensional generaliza-

tions of the relative and absolute inequality

indices: the AtkinsonKolmSen approach,

Journal of Economic Theory, 67, pp. 251265.

Veneri, P. (2013) The identification of sub-

centres in two Italian metropolitan

areas: a functional approach, Cities, 31, pp.

177185.

Weymark, J. A. (2006) The normative approach

to the measurement of multidimensional

inequality, in: F. Farina and E. Savaglio (Eds)

Inequality and Economic Integration, ch. 12.

London: Routledge.

White, M. J. (1983) The measurement of spatial

segregation, The American Journal of Sociol-

ogy, 88, pp. 10081018.

Wong, D. W. S. (1993) Spatial indices of segrega-

tion, Urban Studies, 30, pp. 559572.

Appendix. Derivation of the

Correction Term q in the

Equity-adjusted QoL Index

To derive the correction term q in (5), we

assume a Cobb-Douglas specification for the

evaluation function w:

w(z

i

) =

k

j =1

z

s

j

ij

A1

This specification has several advantages

(1) From the theoretical point of view, the

CobbDouglas form gives a multidimen-

sional index q that generalises the Atkinson

(1970) index and is supported by solid

axiomatics.

14

(2) From the computational point of view, the

CobbDouglas allows one to obtain q by

aggregating k univariate inequality indexes

of the Atkinson type (computed for each

amenity separately) and a residual term

accounting for the interaction among the

distribution of amenities within the city.

(3) The value of q depends on a list of k para-

meters s

j

, with j =1, :: , k, with a clear inter-

pretation: each parameter s

j

indicates the

level of aversion to the unequal distribution

of the amenity z

j

associated with it.

The aggregation property for q and the cali-

bration of parametersthat is the choice of

numerical values for the parametersare

now illustrated. To get q, k unidimensional

indices of the Atkinson type must be

computed

l

j

=

1

z

j

1

n

n

i =1

z

s

j

ij

_ _1

s

j

with j =1, :: , k A2

These indices are interesting in themselves

because they reflect the unequal availability of

the different amenities across city districts.

15

Moreover, one can delve into the contribu-

tion of the distribution of each amenity to the

correction termq, by exploiting the following

Proposition 2: (Abul Naga and Geoffard, 2006)

If w(z

i

) =

k

j =1

z

s

j

ij

, and

k

j =1

s

j

\1; :::, the cor-

rection term q can be decomposed as follows

k

j =1

s

j

_ _

ln q=

k

j =1

s

j

ln l

j

+ ln k A3

where, l

j

are the univariate indices of the

Atkinson class defined in (A2) and k is an inter-

action term equal to

16

k =

n

k1

n

i =1

k

j =1

z

s

j

ij

_ _

k

j =1

n

i =1

z

s

j

ij

_ _ A4

Moving on now to the calibration problem,

notice that equations (A2), (A3) and (A4) depend

on the vector of parameters s= s

1

, :: , s

k

. In

(A2), they enter as parameters of the univariate

indices of the Atkinson type. The higher s

j

, for j

= 1, ., k, the lower aversion to an unequal distri-

bution of the amenity j within the city. A numeri-

cal value must be assigned to s

j

with j = 1, ., k

to carry out the empirical analysis.

17

We first nor-

malise s= s

1

, ., s

k

as follows

s

j

=

1 e

j

k 1

A5

where,

k

j =1

e

j

=1. The normalisation gives a

double advantage: the sum of the k values of s

j

is

1 andmore importantlybecause of the isoe-

lastic form of (A2), the normalisation allows

expressing the Pratt (1964) coefficient of relative

risk (inequality) aversion over the distribution of

EQUITY IN THE CITY 3221

at CEPT University on July 28, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

amenity j, that is 1 s

j

, as an affine function of

e

j

(1 s

j

coincides with e

j

for k = 2). In this way,

each e

j

represents specific preferences vis-a-vis

inequality. In the benchmark case of an identical

degree of inequality aversion for each amenity,

1 s

j

approaches 1 if the number of amenities

goes to infinite, while it is equal to if k = 2.

Notice that and 1 are the two parameters usu-

ally chosen by the Luxembourg Income Study

for the Atkinson index.

18

In our analysis, the

degree of inequality aversion is allowed to vary

with amenities. Since implicit prices truly cap-

ture the assessment of each amenity by the citys

representative citizen, we pragmatically assume

that the higher the contribution of an amenity in

determining the QoL value in the city, the more

intense is the aversion for its uneven distribution

within the city. This is enshrined in the following

assumption

Assumption: The relative inequality aversion coef-

ficient e

j

, with j = 1, ., k, is set to be equal to

e

j

=

p

j

z

j

k

l =1

p

l

z

l

A6

Each parameter e

j

is set to be equal to the ratio

between the estimated value of the average

quantity of the amenity j and the value of all

amenities which are on average available in the

city. In other terms, e

j

corresponds to the relative

contribution of amenity j to the overall QoL

index.

All in all, the methodology can be summarised

in the following steps

(1) The available amenities z

ij

are computed

using expression (2).

(2) The implicit prices of the k available ame-

nities are estimated through the hedonic

regression (7).

These two steps are sufficient to compute the

QoL index adjusted for the availability of the

amenities (4). To compute the equity-adjusted

QoL index (5) the procedure also includes the

following three steps

(1) The coefficients e

j

, with j=1,..,k, are com-

puted from equation (A6).

(2) Vectors s= s

1

, . . . , s

k

and l =

l

1

, . . . , l

k

are computed using expres-

sions (A5) and (A2) respectively.

(3) The correction term q is obtained from

equation (A3) and QoL

q

(Z; W) is finally

determined.

3222 MARCO BRAMBILLA ET AL.

at CEPT University on July 28, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Table A1. List of neighbourhoods in Milan

Zone Neighbourhood name Inhabitants Average income (e)S QoL (e)

Centre

1 Scala, Manzoni, Vittorio Emanuele, S. Babila 3 265 60 257 263 453

2 Brera, Duomo, Cordusio, Torino 7 712 61 387 146 553

3 Missori, Italia, Vetra, SantEufemia 6 134 45 529 161 974

4 Diaz, Fontana, Europa 4 448 51 638 179 833

5 Cadorna, Monti, Boccaccio 6 493 57 335 130 176

6 Castello, Melzi dEril, Sarpi 24 478 30 850 74 775

7 Turati, Moscova, Repubblica 7 975 41 599 138 516

8 Venezia, Majno, Monforte 2 658 76 556 194 809

9 Mascagni, Porta Vittoria, Porta Romana 16 355 49 959 99 891

10 Porta Ticinese, Porta Genova, Magenta 18 958 33 647 103 477

Mid centre

11 Cenisio, Procaccini, Firenze 26 088 20 024 52.749

12 Fiera, Giulio Cesare, Sempione 19 756 28 289 77.183

13 Amendola, Monte Rosa, Buonarroti 17 566 32 762 74.483

14 Pagano, Monti, Wagner 8 448 44 901 107.130

15 Piemonte, Washington, Cimarosa 32 651 28 928 90.539

16 Solari, Napoli, Savona 10 757 23 921 101.283

17 Naviglio Grande, Argelati, San Gottardo 13 353 18 715 68.724

18 Tabacchi, Sarfatti, Crema 31 802 21 618 65.100

19 Libia, XXII Marzo, Indipendenza 52 173 22 264 56.482

20 Regina Giovanna, Pisacane, Castel Morrone 22 410 26 847 90.670

21 Abruzzi, Eustachi, Plinio 22 906 26 321 106.415

22 Stazione Centrale, Gioia, Zara 50 087 22 457 82.059

Outlying

23 Musocco, Varesina, Certosa 36 200 14 740 35 251

24 Bovisa, Bausan, Imbonati 32 519 14 595 42 884

25 Largo Boccioni, Aldini, Lopez 15 514 11 887 35 848

26 Bovisasca, Affori, P. Rossi 43 240 14 335 40 679

27 Niguarda, Ornato 25 397 14 411 51 490

28 Fulvio Testi, Bicocca, Ca Granda 26 694 15 885 62 749

29 Monza, Precotto, Gorla 30 814 15 458 50 086

30 Zara, Istria, Murat 14 361 16 034 52 883

31 Loreto, Turro, Padova 51 457 16 813 69 693

32 Parco Lambro, Feltre, Udine 56 571 14 993 47 346

33 Aspromonte, Porpora, Teodosio 26 259 19 721 67 789

34 Leonardo da Vinci, Gorini 19 303 20 247 65 149

35 Lambrate, Rubattino, Folli 6 768 16 518 42 878

36 Argonne, Viale Corsica 27 318 20 777 59 496

37 Forlanini, Mecenate, Rogoredo 32 255 14 540 34 697

38 Ortomercato, Molise, Piranesi 12 071 18 783 50 896

39 Boncompagni, Toffetti, Bacchiglione 11 933 17 235 41 159

40 Omero, Gabriele Rosa, Brenta 20 996 13 447 34 283

41 Ronchetto, Chiaravalle, Ripamonti 12 158 17 404 37 389

42 Montegani, Cermenate, Vigentino 45 664 16 991 49 032

(continued)

EQUITY IN THE CITY 3223

at CEPT University on July 28, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Table A1. (Continued)

Zone Neighbourhood name Inhabitants Average income (e)S QoL (e)

43 Barona, Famagosta, Faenza 46 458 14 761 50 401

44 San Cristoforo, Ronchetto, Ludovico il Moro 22 260 12 360 55 367

45 Giambellino, Tirana, Frattini 27 723 16 396 45 903

46 Siena, Tripoli, Brasilia 42 150 19 313 66 706

47 Lorenteggio, Inganni, Bisceglie 41 657 14 848 50 972

48 Novara, San Carlo, Amati 9 704 14 729 47 383

49 Segesta, Capecelatro, Aretusa 29 543 16 204 46 154

50 Ippodromo, Caprilli, Monte Stella 5 070 27 664 91 340

51 Cagnola, Achille, Papa, Tiro Segno 5 826 19 907 52 780

Suburbs

52 Baggio, Quinto Romano, Quarto Cagnino 45 757 14 107 36 115

53 Gallaratese, Lampugnano, Figino 44 020 18 652 66 154

54 Missaglia, Chiesa Rossa, Gratosoglio 20 624 12 595 40 792

55 Quarto Oggiaro, Roserio, Amoretti 17 894 11 791 30 096

Table A2. Description of variables

Variable Definition Source

Market_p 1 if the housing value is a market price (ref.) OMI

Offer_p 1 if the housing value is an offer price OMI

Estimated_p 1 if the housing value estimated by OMI OMI

Private characteristics

ln(size) logarithm of the total floor surface area OMI

Second bathroom 1 if the unit has a second bathroom, or more OMI

Third bathroom 1 if the unit has a third bathroom, or more OMI

To be renewed 1 if the unit needs to be renewed OMI

Heating 1 if the unit has gas central heating OMI

2nd floor (or higher) 1 if the unit is on second floor, or higher OMI

Low cost 1 if the unit is in a low-cost building (ref.) OMI

Medium cost 1 if the unit is in a medium-cost building OMI

Luxury 1 if the unit is in a luxury building OMI

Parking 1 if the unit has at least one parking space OMI

Elevator 1 if the unit is in a building with an elevator OMI

ln(age) logarithm of the age of building OMI

Distance distance of the unit to the centre Authors computation

City centre 1 if the unit is one of the zones in the centre OMI

Amenities

Transport number of metro stations Milan Transport Agency

Proximity_university proximity to the nearest university Authors computation

Green percentage of public green areas Milan Municipality

Cultural cultural places

a

per 10 000 inhabitants Yellow Pages

Shopping_facilities commercial facilities

b

per 10 000 inhabitants Authors computation

Ethnic Italian/foreign Milan Municipality

a

Cinemas, theatres, museums, art galleries, academies of music and libraries.

b

Supermarkets, discount stores and malls.

3224 MARCO BRAMBILLA ET AL.

at CEPT University on July 28, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- From Neighborhoods to Nations: The Economics of Social InteractionsDa EverandFrom Neighborhoods to Nations: The Economics of Social InteractionsNessuna valutazione finora

- Archibugi, Franco. 2001Documento22 pagineArchibugi, Franco. 2001Ygor Santos MeloNessuna valutazione finora

- Measuring Growth and Change in Metropolitan FormDocumento66 pagineMeasuring Growth and Change in Metropolitan FormJohn Alexander AzueroNessuna valutazione finora

- Evaluation of The Urban Strategic Planni PDFDocumento18 pagineEvaluation of The Urban Strategic Planni PDFpritiNessuna valutazione finora

- Abstracts ExamplesDocumento5 pagineAbstracts ExamplesJeyakaran TNessuna valutazione finora

- Proximal Cities: Does Walkability Drive Informal Settlements?Documento20 pagineProximal Cities: Does Walkability Drive Informal Settlements?Tap TouchNessuna valutazione finora

- Ávila Nuñez Et Al. - 2020 - Multidimensional Characterization of Periurban Transects. Mexican Case StudyDocumento14 pagineÁvila Nuñez Et Al. - 2020 - Multidimensional Characterization of Periurban Transects. Mexican Case StudydonmozartwaNessuna valutazione finora

- Understanding Commuting Patterns and Changes: Counterfactual Analysis in Planning Support FrameworkDocumento16 pagineUnderstanding Commuting Patterns and Changes: Counterfactual Analysis in Planning Support FrameworkTesta FerreiraNessuna valutazione finora

- Exploring The Associations Between Urban Form and Neighborhood Vibrancy: A Case Study of Chengdu, ChinaDocumento15 pagineExploring The Associations Between Urban Form and Neighborhood Vibrancy: A Case Study of Chengdu, Chinamsa65851Nessuna valutazione finora

- 106 380 1 PBDocumento29 pagine106 380 1 PBAlexandru-Ionut PETRISORNessuna valutazione finora

- Long and Huang 2019 EPB - VitalityDocumento17 pagineLong and Huang 2019 EPB - VitalityAndrew 28Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sustainability 11 00479Documento16 pagineSustainability 11 00479malayNessuna valutazione finora

- Beirut Dynamics Aamas16 WorkshopDocumento18 pagineBeirut Dynamics Aamas16 WorkshopMd mostafizur RahmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Smart City As A Tool of Citizen-Oriented Urban Regeneration: Framework of Preliminary Evaluation and Its ApplicationDocumento20 pagineSmart City As A Tool of Citizen-Oriented Urban Regeneration: Framework of Preliminary Evaluation and Its ApplicationHaram MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- Constituents of Quality of Life and Urban SizeDocumento24 pagineConstituents of Quality of Life and Urban SizeAlberto VazquezNessuna valutazione finora

- Interactive Model of Urban Development in Residential Areas in SkopjeDocumento12 pagineInteractive Model of Urban Development in Residential Areas in Skopjesarabiba1971Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Large Scale, App-Based Behaviour Change Experiment Persuading Sustainable Mobility Patterns: Methods, Results and Lessons LearntDocumento23 pagineA Large Scale, App-Based Behaviour Change Experiment Persuading Sustainable Mobility Patterns: Methods, Results and Lessons LearntdianaNessuna valutazione finora

- Urban Informatics WorkbookDocumento110 pagineUrban Informatics WorkbookActiveUrbesNessuna valutazione finora

- Eco-Cities An Integrated System Dynamics Framework and A Concise Research TaxonomyDocumento14 pagineEco-Cities An Integrated System Dynamics Framework and A Concise Research Taxonomysharmakabir89Nessuna valutazione finora

- Smart City Trough PraticeDocumento16 pagineSmart City Trough PraticeBrankoNessuna valutazione finora