Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Partnership (Rights of Partner) Full Cases

Caricato da

Lourdes AngelieCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Partnership (Rights of Partner) Full Cases

Caricato da

Lourdes AngelieCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

EN BANC

G.R. No. 5840 September 17, 1910

THE UNITED STATES, plaintiff-appellee,

vs.

EUSEBIO CLARIN, defendant-appellant.

Francisco Dominguez, for appellant.

Attorney-General Villamor, for appellee.

ARELLANO, C.J .:

Pedro Larin delivered to Pedro Tarug P172, in order that the latter, in company with Eusebio

Clarin and Carlos de Guzman, might buy and sell mangoes, and, believing that he could make

some money in this business, the said Larin made an agreement with the three men by which the

profits were to be divided equally between him and them.

Pedro Tarug, Eusebio Clarin, and Carlos de Guzman did in fact trade in mangoes and obtained

P203 from the business, but did not comply with the terms of the contract by delivering to Larin

his half of the profits; neither did they render him any account of the capital.

Larin charged them with the crime of estafa, but the provincial fiscal filed an information only

against Eusebio Clarin in which he accused him of appropriating to himself not only the P172

but also the share of the profits that belonged to Larin, amounting to P15.50.

Pedro Tarug and Carlos de Guzman appeared in the case as witnesses and assumed that the facts

presented concerned the defendant and themselves together.

The trial court, that of First Instance of Pampanga, sentenced the defendant, Eusebio Clarin, to

six months' arresto mayor, to suffer the accessory penalties, and to return to Pedro Larin P172,

besides P30.50 as his share of the profits, or to subsidiary imprisonment in case of insolvency,

and to pay the costs. The defendant appealed, and in deciding his appeal we arrive at the

following conclusions:

When two or more persons bind themselves to contribute money, property, or industry to a

common fund, with the intention of dividing the profits among themselves, a contract is formed

which is called partnership. (Art. 1665, Civil Code.)

When Larin put the P172 into the partnership which he formed with Tarug, Clarin, and Guzman,

he invested his capital in the risks or benefits of the business of the purchase and sale of

mangoes, and, even though he had reserved the capital and conveyed only the usufruct of his

money, it would not devolve upon of his three partners to return his capital to him, but upon the

partnership of which he himself formed part, or if it were to be done by one of the three

specifically, it would be Tarug, who, according to the evidence, was the person who received the

money directly from Larin.

The P172 having been received by the partnership, the business commenced and profits accrued,

the action that lies with the partner who furnished the capital for the recovery of his money is not

a criminal action for estafa, but a civil one arising from the partnership contract for a liquidation

of the partnership and a levy on its assets if there should be any.

No. 5 of article 535 of the Penal Code, according to which those are guilty of estafa "who, to the

prejudice of another, shall appropriate or misapply any money, goods, or any kind of personal

property which they may have received as a deposit on commission for administration or in any

other character producing the obligation to deliver or return the same," (as, for example, in

commodatum, precarium, and other unilateral contracts which require the return of the same

thing received) does not include money received for a partnership; otherwise the result would be

that, if the partnership, instead of obtaining profits, suffered losses, as it could not be held liable

civilly for the share of the capitalist partner who reserved the ownership of the money brought in

by him, it would have to answer to the charge of estafa, for which it would be sufficient to argue

that the partnership had received the money under obligation to return it.

We therefore freely acquit Eusebio Clarin, with the costs de oficio. The complaint for estafa is

dismissed without prejudice to the institution of a civil action.

Torres, Johnson, Moreland and Trent, JJ., concur.

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

EN BANC

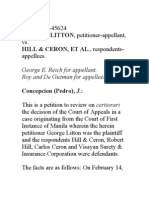

G.R. No. L-45624 April 25, 1939

GEORGE LITTON, petitioner-appellant,

vs.

HILL & CERON, ET AL., respondents-appellees.

George E. Reich for appellant.

Roy and De Guzman for appellees.

Espeleta, Quijano and Liwag for appellee Hill.

CONCEPCION, J .:

This is a petition to review on certiorari the decision of the Court of Appeals in a case

originating from the Court of First Instance of Manila wherein the herein petitioner George

Litton was the plaintiff and the respondents Hill & Ceron, Robert Hill, Carlos Ceron and Visayan

Surety & Insurance Corporation were defendants.

The facts are as follows: On February 14, 1934, the plaintiff sold and delivered to Carlos Ceron,

who is one of the managing partners of Hill & Ceron, a certain number of mining claims, and by

virtue of said transaction, the defendant Carlos Ceron delivered to the plaintiff a document

reading as follows:

Feb. 14, 1934

Received from Mr. George Litton share certificates Nos. 4428, 4429 and 6699 for 5,000,

5,000 and 7,000 shares respectively total 17,000 shares of Big Wedge Mining

Company, which we have sold at P0.11 (eleven centavos) per share or P1,870.00 less 1/2

per cent brokerage.

HILL & CERON

By: (Sgd.) CARLOS CERON

Ceron paid to the plaintiff the sum or P1,150 leaving an unpaid balance of P720, and unable to

collect this sum either from Hill & Ceron or from its surety Visayan Surety & Insurance

Corporation, Litton filed a complaint in the Court of First Instance of Manila against the said

defendants for the recovery of the said balance. The court, after trial, ordered Carlos Ceron

personally to pay the amount claimed and absolved the partnership Hill & Ceron, Robert Hill and

the Visayan Surety & Insurance Corporation. On appeal to the Court of Appeals, the latter

affirmed the decision of the court on May 29, 1937, having reached the conclusion that Ceron

did not intend to represent and did not act for the firm Hill & Ceron in the transaction involved in

this litigation.

Accepting, as we cannot but accept, the conclusion arrived at by the Court of Appeals as to the

question of fact just mentioned, namely, that Ceron individually entered into the transaction with

the plaintiff, but in view, however, of certain undisputed facts and of certain regulations and

provisions of the Code of Commerce, we reach the conclusion that the transaction made by

Ceron with the plaintiff should be understood in law as effected by Hill & Ceron and binding

upon it.

In the first place, it is an admitted fact by Robert Hill when he testified at the trial that he and

Ceron, during the partnership, had the same power to buy and sell; that in said partnership Hill as

well as Ceron made the transaction as partners in equal parts; that on the date of the transaction,

February 14, 1934, the partnership between Hill and Ceron was in existence. After this date, or

on February 19th, Hill & Ceron sold shares of the Big Wedge; and when the transaction was

entered into with Litton, it was neither published in the newspapers nor stated in the commercial

registry that the partnership Hill & Ceron had been dissolved.

Hill testified that a few days before February 14th he had a conversation with the plaintiff in the

course of which he advised the latter not to deliver shares for sale or on commission to Ceron

because the partnership was about to be dissolved; but what importance can be attached to said

advice if the partnership was not in fact dissolved on February 14th, the date when the

transaction with Ceron took place?

Under article 226 of the Code of Commerce, the dissolution of a commercial association shall

not cause any prejudice to third parties until it has been recorded in the commercial registry. (See

also Cardell vs. Maeru, 14 Phil., 368.) The Supreme Court of Spain held that the dissolution of

a partnership by the will of the partners which is not registered in the commercial registry, does

not prejudice third persons. (Opinion of March 23, 1885.)

Aside from the aforecited legal provisions, the order of the Bureau of Commerce of December 7,

1933, prohibits brokers from buying and selling shares on their own account. Said order reads:

The stock and/or bond broker is, therefore, merely an agent or an intermediary, and as

such, shall not be allowed. . . .

(c) To buy or to sell shares of stock or bonds on his own account for purposes of

speculation and/or for manipulating the market, irrespective of whether the purchase or

sale is made from or to a private individual, broker or brokerage firm.

In its decision the Court of Appeals states:

But there is a stronger objection to the plaintiff's attempt to make the firm responsible to

him. According to the articles of copartnership of 'Hill & Ceron,' filed in the Bureau of

Commerce.

Sixth. That the management of the business affairs of the copartnership shall be entrusted

to both copartners who shall jointly administer the business affairs, transactions and

activities of the copartnership, shall jointly open a current account or any other kind of

account in any bank or banks, shall jointly sign all checks for the withdrawal of funds and

shall jointly or singly sign, in the latter case, with the consent of the other partner. . . .

Under this stipulation, a written contract of the firm can only be signed by one of the

partners if the other partner consented. Without the consent of one partner, the other

cannot bind the firm by a written contract. Now, assuming for the moment that Ceron

attempted to represent the firm in this contract with the plaintiff (the plaintiff conceded

that the firm name was not mentioned at that time), the latter has failed to prove that Hill

had consented to such contract.

It follows from the sixth paragraph of the articles of partnership of Hill &n Ceron above quoted

that the management of the business of the partnership has been entrusted to both partners

thereof, but we dissent from the view of the Court of Appeals that for one of the partners to bind

the partnership the consent of the other is necessary. Third persons, like the plaintiff, are not

bound in entering into a contract with any of the two partners, to ascertain whether or not this

partner with whom the transaction is made has the consent of the other partner. The public need

not make inquires as to the agreements had between the partners. Its knowledge, is enough that it

is contracting with the partnership which is represented by one of the managing partners.

There is a general presumption that each individual partner is an authorized agent for the

firm and that he has authority to bind the firm in carrying on the partnership transactions.

(Mills vs. Riggle, 112 Pac., 617.)

The presumption is sufficient to permit third persons to hold the firm liable on

transactions entered into by one of members of the firm acting apparently in its behalf

and within the scope of his authority. (Le Roy vs. Johnson, 7 U. S. [Law. ed.], 391.)

The second paragraph of the articles of partnership of Hill & Ceron reads in part:

Second: That the purpose or object for which this copartnership is organized is to engage

in the business of brokerage in general, such as stock and bond brokers, real brokers,

investment security brokers, shipping brokers, and other activities pertaining to the

business of brokers in general.

The kind of business in which the partnership Hill & Ceron is to engage being thus determined,

none of the two partners, under article 130 of the Code of Commerce, may legally engage in the

business of brokerage in general as stock brokers, security brokers and other activities pertaining

to the business of the partnership. Ceron, therefore, could not have entered into the contract of

sale of shares with Litton as a private individual, but as a managing partner of Hill & Ceron.

The respondent argues in its brief that even admitting that one of the partners could not, in his

individual capacity, engage in a transaction similar to that in which the partnership is engaged

without binding the latter, nevertheless there is no law which prohibits a partner in the stock

brokerage business for engaging in other transactions different from those of the partnership, as

it happens in the present case, because the transaction made by Ceron is a mere personal loan,

and this argument, so it is said, is corroborated by the Court of Appeals. We do not find this

alleged corroboration because the only finding of fact made by the Court of Appeals is to the

effect that the transaction made by Ceron with the plaintiff was in his individual capacity.

The appealed decision is reversed and the defendants are ordered to pay to the plaintiff, jointly

and severally, the sum of P720, with legal interest, from the date of the filing of the complaint,

minus the commission of one-half per cent (%) from the original price of P1,870, with the

costs to the respondents. So ordered.

Avancea, C. J., Villa-Real, Imperial, Diaz, Laurel, and Moran, JJ., concur.

RESOLUTION

July 13, 1939

CONCEPCION, J.:

A motion has been presented in this case by Robert Hill, one of the defendants sentenced in our

decision to pay to the plaintiff the amount claimed in his complaint. It is asked that we reconsider

our decision, the said defendant insisting that the appellant had not established that Carlos Ceron,

another of the defendants, had the consent of his copartner, the movant, to enter with the

appellant into the contract whose breach gave rise to the complaint. It is argued that, it being

stipulated in the articles of partnership that Hill and Ceron, only partners of the firm Hill &

Ceron, would, as managers, have the management of the business of the partnership, and that

either may contract and sign for the partnership with the consent of the other; the parties of

partnership having been, so it is said, recorded in the commercial registry, the appellant could not

ignore the fact that the consent of the movant was necessary for the validity of the contract which

he had with the other partner and defendant, Ceron, and there being no evidence that said consent

had been obtained, the complaint to compel compliance with the said contract had to be, as it

must be in fact, a procedural failure.

Although this question has already been considered and settled in our decision, we nevertheless

take cognizance of the motion in order to enlarge upon our views on the matter.

The stipulation in the articles of partnership that any of the two managing partners may contract

and sign in the name of the partnership with the consent of the other, undoubtedly creates an

obligation between the two partners, which consists in asking the other's consent before

contracting for the partnership. This obligation of course is not imposed upon a third person who

contracts with the partnership. Neither is it necessary for the third person to ascertain if the

managing partner with whom he contracts has previously obtained the consent of the other. A

third person may and has a right to presume that the partner with whom he contracts has, in the

ordinary and natural course of business, the consent of his copartner; for otherwise he would not

enter into the contract. The third person would naturally not presume that the partner with whom

he enters into the transaction is violating the articles of partnership but, on the contrary, is acting

in accordance therewith. And this finds support in the legal presumption that the ordinary course

of business has been followed (No. 18, section 334, Code of Civil Procedure), and that the law

has been obeyed (No. 31, section 334). This last presumption is equally applicable to contracts

which have the force of law between the parties.

Wherefore, unless the contrary is shown, namely, that one of the partners did not consent to his

copartner entering into a contract with a third person, and that the latter with knowledge thereof

entered into said contract, the aforesaid presumption with all its force and legal effects should be

taken into account.

There is nothing in the case at bar which destroys this presumption; the only thing appearing in

he findings of fact of the Court of Appeals is that the plaintiff "has failed to prove that Hill had

consented to such contract". According to this, it seems that the Court of Appeals is of the

opinion that the two partners should give their consent to the contract and that the plaintiff

should prove it. The clause of the articles of partnership should not be thus understood, for it

means that one of the two partners should have the consent of the other to contract for the

partnership, which is different; because it is possible that one of the partners may not see any

prospect in a transaction, but he may nevertheless consent to the realization thereof by his

copartner in reliance upon his skill and ability or otherwise. And here we have to hold once again

that it is not the plaintiff who, under the articles of partnership, should obtain and prove the

consent of Hill, but the latter's partner, Ceron, should he file a complaint against the partnership

for compliance with the contract; but in the present case, it is a third person, the plaintiff, who

asks for it. While the said presumption stands, the plaintiff has nothing to prove.

Passing now to another aspect of the case, had Ceron in any way stated to the appellant at the

time of the execution of the contract, or if it could be inferred by his conduct, that he had the

consent of Hill, and should it turn out later that he did not have such consent, this alone would

not annul the contract judging from the provisions of article 130 of the Code of Commerce

reading as follows:

No new obligation shall be contracted against the will of one of the managing partners,

should he have expressly stated it; but if, however, it should be contracted it shall not be

annulled for this reason, and shall have its effects without prejudice to the liability of the

partner or partners who contracted it to reimburse the firm for any loss occasioned by

reason thereof. (Emphasis supplied.)

Under the aforequoted provisions, when, not only without the consent but against the will of any

of the managing partners, a contract is entered into with a third person who acts in good faith,

and the transaction is of the kind of business in which the partnership is engaged, as in the

present case, said contract shall not be annulled, without prejudice to the liability of the guilty

partner.

The reason or purpose behind these legal provisions is no other than to protect a third person

who contracts with one of the managing partners of the partnership, thus avoiding fraud and

deceit to which he may easily fall a victim without this protection which the Code of Commerce

wisely provides.

If we are to interpret the articles of partnership in question by holding that it is the obligation of

the third person to inquire whether the managing copartner of the one with whom he contracts

has given his consent to said contract, which is practically casting upon him the obligation to get

such consent, this interpretation would, in similar cases, operate to hinder effectively the

transactions, a thing not desirable and contrary to the nature of business which requires

promptness and dispatch one the basis of good faith and honesty which are always presumed.

In view of the foregoing, and sustaining the other views expressed in the decision, the motion is

denied. So ordered.

Avancea, C. J., Villa-Real, Imperial, Diaz, Laurel, and Moran, JJ., concur.

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

EN BANC

G.R. No. L-22442 August 1, 1924

ANTONIO PARDO, petitioner,

vs.

THE HERCULES LUMBER CO., INC., and IGNACIO FERRER, respondents.

W.J. O'Donovan and M.H. de Joya for petitioner.

Sumulong and Lavides and Ross, Lawrence and Selph for respondents.

STREET, J .:

The petitioner, Antonio Pardo, a stockholder in the Hercules Lumber Company, Inc., one of the

respondents herein, seeks by this original proceeding in the Supreme Court to obtain a writ of

mandamus to compel the respondents to permit the plaintiff and his duly authorized agent and

representative to examine the records and business transactions of said company. To this petition

the respondents interposed an answer, in which, after admitting certain allegations of the petition,

the respondents set forth the facts upon which they mainly rely as a defense to the petition. To

this answer the petitioner in turn interposed a demurrer, and the cause is now before us for

determination of the issue thus presented.

It is inferentially, if not directly admitted that the petitioner is in fact a stockholder in the

Hercules Lumber Company, Inc., and that the respondent, Ignacio Ferrer, as acting secretary of

the said company, has refused to permit the petitioner or his agent to inspect the records and

business transactions of the said Hercules Lumber Company, Inc., at times desired by the

petitioner. No serious question is of course made as to the right of the petitioner, by himself or

proper representative, to exercise the right of inspection conferred by section 51 of Act No. 1459.

Said provision was under the consideration of this court in the case of Philpotts vs. Philippine

Manufacturing Co., and Berry (40 Phil., 471), where we held that the right of examination there

conceded to the stockholder may be exercised either by a stockholder in person or by any duly

authorized agent or representative.

The main ground upon which the defense appears to be rested has reference to the time, or times,

within which the right of inspection may be exercised. In this connection the answer asserts that

in article 10 of the By-laws of the respondent corporation it is declared that "Every shareholder

may examine the books of the company and other documents pertaining to the same upon the

days which the board of directors shall annually fix." It is further averred that at the directors'

meeting of the respondent corporation held on February 16, 1924, the board passed a resolution

to the following effect:

The board also resolved to call the usual general (meeting of shareholders) for March 30 of the

present year, with notice to the shareholders that the books of the company are at their

disposition from the 15th to 25th of the same month for examination, in appropriate hours.

The contention for the respondent is that this resolution of the board constitutes a lawful

restriction on the right conferred by statute; and it is insisted that as the petitioner has not

availed himself of the permission to inspect the books and transactions of the company

within the ten days thus defined, his right to inspection and examination is lost, at least

for this year.

We are entirely unable to concur in this contention. The general right given by the statute may

not be lawfully abridged to the extent attempted in this resolution. It may be admitted that the

officials in charge of a corporation may deny inspection when sought at unusual hours or under

other improper conditions; but neither the executive officers nor the board of directors have the

power to deprive a stockholder of the right altogether. A by-law unduly restricting the right of

inspection is undoubtedly invalid. Authorities to this effect are too numerous and direct to

require extended comment. (14 C.J., 859; 7 R.C.L., 325; 4 Thompson on Corporations, 2nd ed.,

sec. 4517; Harkness vs. Guthrie, 27 Utah, 248; 107 Am., St. Rep., 664. 681.) Under a statute

similar to our own it has been held that the statutory right of inspection is not affected by the

adoption by the board of directors of a resolution providing for the closing of transfer books

thirty days before an election. (State vs. St. Louis Railroad Co., 29 Mo., Ap., 301.)

It will be noted that our statute declares that the right of inspection can be exercised "at

reasonable hours." This means at reasonable hours on business days throughout the year, and not

merely during some arbitrary period of a few days chosen by the directors.

In addition to relying upon the by-law, to which reference is above made, the answer of the

respondents calls in question the motive which is supposed to prompt the petitioner to make

inspection; and in this connection it is alleged that the information which the petitioner seeks is

desired for ulterior purposes in connection with a competitive firm with which the petitioner is

alleged to be connected. It is also insisted that one of the purposes of the petitioner is to obtain

evidence preparatory to the institution of an action which he means to bring against the

corporation by reason of a contract of employment which once existed between the corporation

and himself. These suggestions are entirely apart from the issue, as, generally speaking, the

motive of the shareholder exercising the right is immaterial. (7 R.C.L., 327.)

We are of the opinion that, upon the allegations of the petition and the admissions of the answer,

the petitioner is entitled to relief. The demurrer is, therefore, sustained; and the writ of

mandamus will issue as prayed, with the costs against the respondent. So ordered.

Johnson, Malcolm, Villamor, Ostrand, and Romualdez, JJ., concur.

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

THIRD DIVISION

G.R. No. 70926 January 31, 1989

DAN FUE LEUNG, petitioner,

vs.

HON. INTERMEDIATE APPELLATE COURT and LEUNG YIU, respondents.

John L. Uy for petitioner.

Edgardo F. Sundiam for private respondent.

GUTIERREZ, J R., J .:

The petitioner asks for the reversal of the decision of the then Intermediate Appellate Court in

AC-G.R. No. CV-00881 which affirmed the decision of the then Court of First Instance of

Manila, Branch II in Civil Case No. 116725 declaring private respondent Leung Yiu a partner of

petitioner Dan Fue Leung in the business of Sun Wah Panciteria and ordering the petitioner to

pay to the private respondent his share in the annual profits of the said restaurant.

This case originated from a complaint filed by respondent Leung Yiu with the then Court of First

Instance of Manila, Branch II to recover the sum equivalent to twenty-two percent (22%) of the

annual profits derived from the operation of Sun Wah Panciteria since October, 1955 from

petitioner Dan Fue Leung.

The Sun Wah Panciteria, a restaurant, located at Florentino Torres Street, Sta. Cruz, Manila, was

established sometime in October, 1955. It was registered as a single proprietorship and its

licenses and permits were issued to and in favor of petitioner Dan Fue Leung as the sole

proprietor. Respondent Leung Yiu adduced evidence during the trial of the case to show that Sun

Wah Panciteria was actually a partnership and that he was one of the partners having contributed

P4,000.00 to its initial establishment.

The private respondents evidence is summarized as follows:

About the time the Sun Wah Panciteria started to become operational, the private respondent

gave P4,000.00 as his contribution to the partnership. This is evidenced by a receipt identified as

Exhibit "A" wherein the petitioner acknowledged his acceptance of the P4,000.00 by affixing his

signature thereto. The receipt was written in Chinese characters so that the trial court

commissioned an interpreter in the person of Ms. Florence Yap to translate its contents into

English. Florence Yap issued a certification and testified that the translation to the best of her

knowledge and belief was correct. The private respondent identified the signature on the receipt

as that of the petitioner (Exhibit A-3) because it was affixed by the latter in his (private

respondents') presence. Witnesses So Sia and Antonio Ah Heng corroborated the private

respondents testimony to the effect that they were both present when the receipt (Exhibit "A")

was signed by the petitioner. So Sia further testified that he himself received from the petitioner

a similar receipt (Exhibit D) evidencing delivery of his own investment in another amount of

P4,000.00 An examination was conducted by the PC Crime Laboratory on orders of the trial

court granting the private respondents motion for examination of certain documentary exhibits.

The signatures in Exhibits "A" and 'D' when compared to the signature of the petitioner

appearing in the pay envelopes of employees of the restaurant, namely Ah Heng and Maria

Wong (Exhibits H, H-1 to H-24) showed that the signatures in the two receipts were indeed the

signatures of the petitioner.

Furthermore, the private respondent received from the petitioner the amount of P12,000.00

covered by the latter's Equitable Banking Corporation Check No. 13389470-B from the profits of

the operation of the restaurant for the year 1974. Witness Teodulo Diaz, Chief of the Savings

Department of the China Banking Corporation testified that said check (Exhibit B) was deposited

by and duly credited to the private respondents savings account with the bank after it was cleared

by the drawee bank, the Equitable Banking Corporation. Another witness Elvira Rana of the

Equitable Banking Corporation testified that the check in question was in fact and in truth drawn

by the petitioner and debited against his own account in said bank. This fact was clearly shown

and indicated in the petitioner's statement of account after the check (Exhibit B) was duly

cleared. Rana further testified that upon clearance of the check and pursuant to normal banking

procedure, said check was returned to the petitioner as the maker thereof.

The petitioner denied having received from the private respondent the amount of P4,000.00. He

contested and impugned the genuineness of the receipt (Exhibit D). His evidence is summarized

as follows:

The petitioner did not receive any contribution at the time he started the Sun Wah Panciteria. He

used his savings from his salaries as an employee at Camp Stotsenberg in Clark Field and later as

waiter at the Toho Restaurant amounting to a little more than P2,000.00 as capital in establishing

Sun Wah Panciteria. To bolster his contention that he was the sole owner of the restaurant, the

petitioner presented various government licenses and permits showing the Sun Wah Panciteria

was and still is a single proprietorship solely owned and operated by himself alone. Fue Leung

also flatly denied having issued to the private respondent the receipt (Exhibit G) and the

Equitable Banking Corporation's Check No. 13389470 B in the amount of P12,000.00 (Exhibit

B).

As between the conflicting evidence of the parties, the trial court gave credence to that of the

plaintiffs. Hence, the court ruled in favor of the private respondent. The dispositive portion of the

decision reads:

WHEREFORE, judgment is hereby rendered in favor of the plaintiff and against

the defendant, ordering the latter to deliver and pay to the former, the sum

equivalent to 22% of the annual profit derived from the operation of Sun Wah

Panciteria from October, 1955, until fully paid, and attorney's fees in the amount

of P5,000.00 and cost of suit. (p. 125, Rollo)

The private respondent filed a verified motion for reconsideration in the nature of a motion for

new trial and, as supplement to the said motion, he requested that the decision rendered should

include the net profit of the Sun Wah Panciteria which was not specified in the decision, and

allow private respondent to adduce evidence so that the said decision will be comprehensively

adequate and thus put an end to further litigation.

The motion was granted over the objections of the petitioner. After hearing the trial court

rendered an amended decision, the dispositive portion of which reads:

FOR ALL THE FOREGOING CONSIDERATIONS, the motion for

reconsideration filed by the plaintiff, which was granted earlier by the Court, is

hereby reiterated and the decision rendered by this Court on September 30, 1980,

is hereby amended. The dispositive portion of said decision should read now as

follows:

WHEREFORE, judgment is hereby rendered, ordering the plaintiff (sic) and

against the defendant, ordering the latter to pay the former the sum equivalent to

22% of the net profit of P8,000.00 per day from the time of judicial demand, until

fully paid, plus the sum of P5,000.00 as and for attorney's fees and costs of suit.

(p. 150, Rollo)

The petitioner appealed the trial court's amended decision to the then Intermediate Appellate

Court. The questioned decision was further modified by the appellate court. The dispositive

portion of the appellate court's decision reads:

WHEREFORE, the decision appealed from is modified, the dispositive portion

thereof reading as follows:

1. Ordering the defendant to pay the plaintiff by way of temperate damages 22%

of the net profit of P2,000.00 a day from judicial demand to May 15, 1971;

2. Similarly, the sum equivalent to 22% of the net profit of P8,000.00 a day from

May 16, 1971 to August 30, 1975;

3. And thereafter until fully paid the sum equivalent to 22% of the net profit of

P8,000.00 a day.

Except as modified, the decision of the court a quo is affirmed in all other

respects. (p. 102, Rollo)

Later, the appellate court, in a resolution, modified its decision and affirmed the lower court's

decision. The dispositive portion of the resolution reads:

WHEREFORE, the dispositive portion of the amended judgment of the court a

quo reading as follows:

WHEREFORE, judgment is rendered in favor of the plaintiff and against the

defendant, ordering the latter to pay to the former the sum equivalent to 22% of

the net profit of P8,000.00 per day from the time of judicial demand, until fully

paid, plus the sum of P5,000.00 as and for attorney's fees and costs of suit.

is hereby retained in full and affirmed in toto it being understood that the date of judicial demand

is July 13, 1978. (pp. 105-106, Rollo).

In the same resolution, the motion for reconsideration filed by petitioner was denied.

Both the trial court and the appellate court found that the private respondent is a partner of the

petitioner in the setting up and operations of the panciteria. While the dispositive portions merely

ordered the payment of the respondents share, there is no question from the factual findings that

the respondent invested in the business as a partner. Hence, the two courts declared that the

private petitioner is entitled to a share of the annual profits of the restaurant. The petitioner,

however, claims that this factual finding is erroneous. Thus, the petitioner argues: "The

complaint avers that private respondent extended 'financial assistance' to herein petitioner at the

time of the establishment of the Sun Wah Panciteria, in return of which private respondent

allegedly will receive a share in the profits of the restaurant. The same complaint did not claim

that private respondent is a partner of the business. It was, therefore, a serious error for the lower

court and the Hon. Intermediate Appellate Court to grant a relief not called for by the complaint.

It was also error for the Hon. Intermediate Appellate Court to interpret or construe 'financial

assistance' to mean the contribution of capital by a partner to a partnership;" (p. 75, Rollo)

The pertinent portions of the complaint state:

xxx xxx xxx

2. That on or about the latter (sic) of September, 1955, defendant sought the

financial assistance of plaintiff in operating the defendant's eatery known as Sun

Wah Panciteria, located in the given address of defendant; as a return for such

financial assistance. plaintiff would be entitled to twenty-two percentum (22%) of

the annual profit derived from the operation of the said panciteria;

3. That on October 1, 1955, plaintiff delivered to the defendant the sum of four

thousand pesos (P4,000.00), Philippine Currency, of which copy for the receipt of

such amount, duly acknowledged by the defendant is attached hereto as Annex

"A", and form an integral part hereof; (p. 11, Rollo)

In essence, the private respondent alleged that when Sun Wah Panciteria was established, he

gave P4,000.00 to the petitioner with the understanding that he would be entitled to twenty-two

percent (22%) of the annual profit derived from the operation of the said panciteria. These

allegations, which were proved, make the private respondent and the petitioner partners in the

establishment of Sun Wah Panciteria because Article 1767 of the Civil Code provides that "By

the contract of partnership two or more persons bind themselves to contribute money, property or

industry to a common fund, with the intention of dividing the profits among themselves".

Therefore, the lower courts did not err in construing the complaint as one wherein the private

respondent asserted his rights as partner of the petitioner in the establishment of the Sun Wah

Panciteria, notwithstanding the use of the term financial assistance therein. We agree with the

appellate court's observation to the effect that "... given its ordinary meaning, financial assistance

is the giving out of money to another without the expectation of any returns therefrom'. It

connotes an ex gratia dole out in favor of someone driven into a state of destitution. But this

circumstance under which the P4,000.00 was given to the petitioner does not obtain in this case.'

(p. 99, Rollo) The complaint explicitly stated that "as a return for such financial assistance,

plaintiff (private respondent) would be entitled to twenty-two percentum (22%) of the annual

profit derived from the operation of the said panciteria.' (p. 107, Rollo) The well-settled doctrine

is that the '"... nature of the action filed in court is determined by the facts alleged in the

complaint as constituting the cause of action." (De Tavera v. Philippine Tuberculosis Society,

Inc., 113 SCRA 243; Alger Electric, Inc. v. Court of Appeals, 135 SCRA 37).

The appellate court did not err in declaring that the main issue in the instant case was whether or

not the private respondent is a partner of the petitioner in the establishment of Sun Wah

Panciteria.

The petitioner also contends that the respondent court gravely erred in giving probative value to

the PC Crime Laboratory Report (Exhibit "J") on the ground that the alleged standards or

specimens used by the PC Crime Laboratory in arriving at the conclusion were never testified to

by any witness nor has any witness identified the handwriting in the standards or specimens

belonging to the petitioner. The supposed standards or specimens of handwriting were marked as

Exhibits "H" "H-1" to "H-24" and admitted as evidence for the private respondent over the

vigorous objection of the petitioner's counsel.

The records show that the PC Crime Laboratory upon orders of the lower court examined the

signatures in the two receipts issued separately by the petitioner to the private respondent and So

Sia (Exhibits "A" and "D") and compared the signatures on them with the signatures of the

petitioner on the various pay envelopes (Exhibits "H", "H-1" to 'H-24") of Antonio Ah Heng and

Maria Wong, employees of the restaurant. After the usual examination conducted on the

questioned documents, the PC Crime Laboratory submitted its findings (Exhibit J) attesting that

the signatures appearing in both receipts (Exhibits "A" and "D") were the signatures of the

petitioner.

The records also show that when the pay envelopes (Exhibits "H", "H-1" to "H-24") were

presented by the private respondent for marking as exhibits, the petitioner did not interpose any

objection. Neither did the petitioner file an opposition to the motion of the private respondent to

have these exhibits together with the two receipts examined by the PC Crime Laboratory despite

due notice to him. Likewise, no explanation has been offered for his silence nor was any hint of

objection registered for that purpose.

Under these circumstances, we find no reason why Exhibit "J" should be rejected or ignored. The

records sufficiently establish that there was a partnership.

The petitioner raises the issue of prescription. He argues: The Hon. Respondent Intermediate

Appellate Court gravely erred in not resolving the issue of prescription in favor of petitioner. The

alleged receipt is dated October 1, 1955 and the complaint was filed only on July 13, 1978 or

after the lapse of twenty-two (22) years, nine (9) months and twelve (12) days. From October 1,

1955 to July 13, 1978, no written demands were ever made by private respondent.

The petitioner's argument is based on Article 1144 of the Civil Code which provides:

Art. 1144. The following actions must be brought within ten years from the time

the right of action accrues:

(1) Upon a written contract;

(2) Upon an obligation created by law;

(3) Upon a judgment.

in relation to Article 1155 thereof which provides:

Art. 1155. The prescription of actions is interrupted when they are filed before the

court, when there is a written extra-judicial demand by the creditor, and when

there is any written acknowledgment of the debt by the debtor.'

The argument is not well-taken.

The private respondent is a partner of the petitioner in Sun Wah Panciteria. The requisites of a

partnership which are 1) two or more persons bind themselves to contribute money, property,

or industry to a common fund; and 2) intention on the part of the partners to divide the profits

among themselves (Article 1767, Civil Code; Yulo v. Yang Chiao Cheng, 106 Phil. 110)-have

been established. As stated by the respondent, a partner shares not only in profits but also in the

losses of the firm. If excellent relations exist among the partners at the start of business and all

the partners are more interested in seeing the firm grow rather than get immediate returns, a

deferment of sharing in the profits is perfectly plausible. It would be incorrect to state that if a

partner does not assert his rights anytime within ten years from the start of operations, such

rights are irretrievably lost. The private respondent's cause of action is premised upon the failure

of the petitioner to give him the agreed profits in the operation of Sun Wah Panciteria. In effect

the private respondent was asking for an accounting of his interests in the partnership.

It is Article 1842 of the Civil Code in conjunction with Articles 1144 and 1155 which is

applicable. Article 1842 states:

The right to an account of his interest shall accrue to any partner, or his legal

representative as against the winding up partners or the surviving partners or the

person or partnership continuing the business, at the date of dissolution, in the

absence or any agreement to the contrary.

Regarding the prescriptive period within which the private respondent may demand an

accounting, Articles 1806, 1807, and 1809 show that the right to demand an accounting exists as

long as the partnership exists. Prescription begins to run only upon the dissolution of the

partnership when the final accounting is done.

Finally, the petitioner assails the appellate court's monetary awards in favor of the private

respondent for being excessive and unconscionable and above the claim of private respondent as

embodied in his complaint and testimonial evidence presented by said private respondent to

support his claim in the complaint.

Apart from his own testimony and allegations, the private respondent presented the cashier of

Sun Wah Panciteria, a certain Mrs. Sarah L. Licup, to testify on the income of the restaurant.

Mrs. Licup stated:

ATTY. HIPOLITO (direct examination to Mrs. Licup).

Q Mrs. Witness, you stated that among your duties was that you

were in charge of the custody of the cashier's box, of the money,

being the cashier, is that correct?

A Yes, sir.

Q So that every time there is a customer who pays, you were the

one who accepted the money and you gave the change, if any, is

that correct?

A Yes.

Q Now, after 11:30 (P.M.) which is the closing time as you said,

what do you do with the money?

A We balance it with the manager, Mr. Dan Fue Leung.

ATTY. HIPOLITO:

I see.

Q So, in other words, after your job, you huddle or confer

together?

A Yes, count it all. I total it. We sum it up.

Q Now, Mrs. Witness, in an average day, more or less, will you

please tell us, how much is the gross income of the restaurant?

A For regular days, I received around P7,000.00 a day during my

shift alone and during pay days I receive more than P10,000.00.

That is excluding the catering outside the place.

Q What about the catering service, will you please tell the

Honorable Court how many times a week were there catering

services?

A Sometimes three times a month; sometimes two times a month

or more.

xxx xxx xxx

Q Now more or less, do you know the cost of the catering service?

A Yes, because I am the one who receives the payment also of the

catering.

Q How much is that?

A That ranges from two thousand to six thousand pesos, sir.

Q Per service?

A Per service, Per catering.

Q So in other words, Mrs. witness, for your shift alone in a single

day from 3:30 P.M. to 11:30 P.M. in the evening the restaurant

grosses an income of P7,000.00 in a regular day?

A Yes.

Q And ten thousand pesos during pay day.?

A Yes.

(TSN, pp. 53 to 59, inclusive, November 15,1978)

xxx xxx xxx

COURT:

Any cross?

ATTY. UY (counsel for defendant):

No cross-examination, Your Honor. (T.S.N. p. 65, November 15,

1978). (Rollo, pp. 127-128)

The statements of the cashier were not rebutted. Not only did the petitioner's counsel waive the

cross-examination on the matter of income but he failed to comply with his promise to produce

pertinent records. When a subpoena duces tecum was issued to the petitioner for the production

of their records of sale, his counsel voluntarily offered to bring them to court. He asked for

sufficient time prompting the court to cancel all hearings for January, 1981 and reset them to the

later part of the following month. The petitioner's counsel never produced any books, prompting

the trial court to state:

Counsel for the defendant admitted that the sales of Sun Wah were registered or

recorded in the daily sales book. ledgers, journals and for this purpose, employed

a bookkeeper. This inspired the Court to ask counsel for the defendant to bring

said records and counsel for the defendant promised to bring those that were

available. Seemingly, that was the reason why this case dragged for quite

sometime. To bemuddle the issue, defendant instead of presenting the books

where the same, etc. were recorded, presented witnesses who claimed to have

supplied chicken, meat, shrimps, egg and other poultry products which, however,

did not show the gross sales nor does it prove that the same is the best evidence.

This Court gave warning to the defendant's counsel that if he failed to produce the

books, the same will be considered a waiver on the part of the defendant to

produce the said books inimitably showing decisive records on the income of the

eatery pursuant to the Rules of Court (Sec. 5(e) Rule 131). "Evidence willfully

suppressed would be adverse if produced." (Rollo, p. 145)

The records show that the trial court went out of its way to accord due process to the petitioner.

The defendant was given all the chance to present all conceivable witnesses, after

the plaintiff has rested his case on February 25, 1981, however, after presenting

several witnesses, counsel for defendant promised that he will present the

defendant as his last witness. Notably there were several postponement asked by

counsel for the defendant and the last one was on October 1, 1981 when he asked

that this case be postponed for 45 days because said defendant was then in

Hongkong and he (defendant) will be back after said period. The Court acting

with great concern and understanding reset the hearing to November 17, 1981. On

said date, the counsel for the defendant who again failed to present the defendant

asked for another postponement, this time to November 24, 1981 in order to give

said defendant another judicial magnanimity and substantial due process. It was

however a condition in the order granting the postponement to said date that if the

defendant cannot be presented, counsel is deemed to have waived the presentation

of said witness and will submit his case for decision.

On November 24, 1981, there being a typhoon prevailing in Manila said date was

declared a partial non-working holiday, so much so, the hearing was reset to

December 7 and 22, 1981. On December 7, 1981, on motion of defendant's

counsel, the same was again reset to December 22, 1981 as previously scheduled

which hearing was understood as intransferable in character. Again on December

22, 1981, the defendant's counsel asked for postponement on the ground that the

defendant was sick. the Court, after much tolerance and judicial magnanimity,

denied said motion and ordered that the case be submitted for resolution based on

the evidence on record and gave the parties 30 days from December 23, 1981,

within which to file their simultaneous memoranda. (Rollo, pp. 148-150)

The restaurant is located at No. 747 Florentino Torres, Sta. Cruz, Manila in front of the Republic

Supermarket. It is near the corner of Claro M. Recto Street. According to the trial court, it is in

the heart of Chinatown where people who buy and sell jewelries, businessmen, brokers,

manager, bank employees, and people from all walks of life converge and patronize Sun Wah.

There is more than substantial evidence to support the factual findings of the trial court and the

appellate court. If the respondent court awarded damages only from judicial demand in 1978 and

not from the opening of the restaurant in 1955, it is because of the petitioner's contentions that all

profits were being plowed back into the expansion of the business. There is no basis in the

records to sustain the petitioners contention that the damages awarded are excessive. Even if the

Court is minded to modify the factual findings of both the trial court and the appellate court, it

cannot refer to any portion of the records for such modification. There is no basis in the records

for this Court to change or set aside the factual findings of the trial court and the appellate court.

The petitioner was given every opportunity to refute or rebut the respondent's submissions but,

after promising to do so, it deliberately failed to present its books and other evidence.

The resolution of the Intermediate Appellate Court ordering the payment of the petitioner's

obligation shows that the same continues until fully paid. The question now arises as to whether

or not the payment of a share of profits shall continue into the future with no fixed ending date.

Considering the facts of this case, the Court may decree a dissolution of the partnership under

Article 1831 of the Civil Code which, in part, provides:

Art. 1831. On application by or for a partner the court shall decree a dissolution

whenever:

xxx xxx xxx

(3) A partner has been guilty of such conduct as tends to affect prejudicially the

carrying on of the business;

(4) A partner willfully or persistently commits a breach of the partnership

agreement, or otherwise so conducts himself in matters relating to the partnership

business that it is not reasonably practicable to carry on the business in

partnership with him;

xxx xxx xxx

(6) Other circumstances render a dissolution equitable.

There shall be a liquidation and winding up of partnership affairs, return of capital, and other

incidents of dissolution because the continuation of the partnership has become inequitable.

WHEREFORE, the petition for review is hereby DISMISSED for lack of merit. The decision of

the respondent court is AFFIRMED with a MODIFICATION that as indicated above, the

partnership of the parties is ordered dissolved.

SO ORDERED.

Fernan, C.J., (Chairman), Feliciano, Bidin and Cortes, JJ., concur.

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

SECOND DIVISION

G.R. No. L-22493 July 31, 1975

ISLAND SALES, INC., plaintiff-appellee,

vs.

UNITED PIONEERS GENERAL CONSTRUCTION COMPANY, ET. AL defendants. BENJAMIN C.

DACO, defendant-appellant.

Grey, Buenaventura and Santiago for plaintiff-appellee.

Anacleto D. Badoy, Jr. for defendant-appellant.

CONCEPCION JR., J .:

This is an appeal interposed by the defendant Benjamin C. Daco from the decision of the Court of First

Instance of Manila, Branch XVI, in Civil Case No. 50682, the dispositive portion of which reads:

WHEREFORE, the Court sentences defendant United Pioneer General Construction

Company to pay plaintiff the sum of P7,119.07 with interest at the rate of 12% per annum

until it is fully paid, plus attorney's fees which the Court fixes in the sum of Eight Hundred

Pesos (P800.00) and costs.

The defendants Benjamin C. Daco, Daniel A. Guizona, Noel C. Sim and Augusto Palisoc

are sentenced to pay the plaintiff in this case with the understanding that the judgment

against these individual defendants shall be enforced only if the defendant company has

no more leviable properties with which to satisfy the judgment against it. .

The individual defendants shall also pay the costs.

On April 22, 1961, the defendant company, a general partnership duly registered under the laws of the

Philippines, purchased from the plaintiff a motor vehicle on the installment basis and for this purpose

executed a promissory note for P9,440.00, payable in twelve (12) equal monthly installments of P786.63,

the first installment payable on or before May 22, 1961 and the subsequent installments on the 22nd day

of every month thereafter, until fully paid, with the condition that failure to pay any of said installments as

they fall due would render the whole unpaid balance immediately due and demandable.

Having failed to receive the installment due on July 22, 1961, the plaintiff sued the defendant company for

the unpaid balance amounting to P7,119.07. Benjamin C. Daco, Daniel A. Guizona, Noel C. Sim, Romulo

B. Lumauig, and Augusto Palisoc were included as co-defendants in their capacity as general partners of

the defendant company.

Daniel A. Guizona failed to file an answer and was consequently declared in default.

1

Subsequently, on motion of the plaintiff, the complaint was dismissed insofar as the defendant Romulo B.

Lumauig is concerned.

2

When the case was called for hearing, the defendants and their counsels failed to appear notwithstanding

the notices sent to them. Consequently, the trial court authorized the plaintiff to present its evidence ex-

parte

3

, after which the trial court rendered the decision appealed from.

The defendants Benjamin C. Daco and Noel C. Sim moved to reconsider the decision claiming that since

there are five (5) general partners, the joint and subsidiary liability of each partner should not exceed one-

fifth (

1

/

5

) of the obligations of the defendant company. But the trial court denied the said motion

notwithstanding the conformity of the plaintiff to limit the liability of the defendants Daco and Sim to only

one-fifth (

1

/

5

) of the obligations of the defendant company.

4

Hence, this appeal.

The only issue for resolution is whether or not the dismissal of the complaint to favor one of the general

partners of a partnership increases the joint and subsidiary liability of each of the remaining partners for

the obligations of the partnership.

Article 1816 of the Civil Code provides:

Art. 1816. All partners including industrial ones, shall be liable pro rata with all their

property and after all the partnership assets have been exhausted, for the contracts

which may be entered into in the name and for the account of the partnership, under its

signature and by a person authorized to act for the partnership. However, any partner

may enter into a separate obligation to perform a partnership contract.

In the case of Co-Pitco vs. Yulo (8 Phil. 544) this Court held:

The partnership of Yulo and Palacios was engaged in the operation of a sugar estate in

Negros. It was, therefore, a civil partnership as distinguished from a mercantile

partnership. Being a civil partnership, by the express provisions of articles l698 and 1137

of the Civil Code, the partners are not liable each for the whole debt of the partnership.

The liability is pro rata and in this case Pedro Yulo is responsible to plaintiff for only one-

half of the debt. The fact that the other partner, Jaime Palacios, had left the country

cannot increase the liability of Pedro Yulo.

In the instant case, there were five (5) general partners when the promissory note in question was

executed for and in behalf of the partnership. Since the liability of the partners is pro rata, the liability of

the appellant Benjamin C. Daco shall be limited to only one-fifth (

1

/

5

) of the obligations of the defendant

company. The fact that the complaint against the defendant Romulo B. Lumauig was dismissed, upon

motion of the plaintiff, does not unmake the said Lumauig as a general partner in the defendant company.

In so moving to dismiss the complaint, the plaintiff merely condoned Lumauig's individual liability to the

plaintiff.

WHEREFORE, the appealed decision as thus clarified is hereby AFFIRMED, without pronouncement as

to costs.

SO ORDERED.

Makalintal, C.J., Fernando (Chairman), Barredo and Aquino, JJ., concur.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Law School Survival Guide (Volume I of II) - Outlines and Case Summaries for Torts, Civil Procedure, Property, Contracts & Sales: Law School Survival GuidesDa EverandLaw School Survival Guide (Volume I of II) - Outlines and Case Summaries for Torts, Civil Procedure, Property, Contracts & Sales: Law School Survival GuidesNessuna valutazione finora

- Litton vs. Hill, 67 Phil. 509Documento9 pagineLitton vs. Hill, 67 Phil. 509Lorjyll Shyne Luberanes TomarongNessuna valutazione finora

- Liton Vs HillDocumento4 pagineLiton Vs HillXing Keet LuNessuna valutazione finora

- Cases Atp Nov 25Documento59 pagineCases Atp Nov 25Nerry Neil TeologoNessuna valutazione finora

- George E. Reich For Appellant. Roy and de Guzman For Appellees. Espeleta, Quijano and Liwag For Appellee HillDocumento68 pagineGeorge E. Reich For Appellant. Roy and de Guzman For Appellees. Espeleta, Quijano and Liwag For Appellee HillCarmela SalazarNessuna valutazione finora

- 25 Litton Vs Hill Ceron Et AlDocumento5 pagine25 Litton Vs Hill Ceron Et Alcertiorari19Nessuna valutazione finora

- 2.) Litton v. Hill and CeronDocumento2 pagine2.) Litton v. Hill and CeronKikoy IlaganNessuna valutazione finora

- Tai TongDocumento12 pagineTai TongJessa F. Austria-CalderonNessuna valutazione finora

- Litton v. Hill & Ceron - 1939Documento7 pagineLitton v. Hill & Ceron - 1939Eugene RoxasNessuna valutazione finora

- Republic of The PhilippinesDocumento3 pagineRepublic of The PhilippinesSuho Leexokleader KimNessuna valutazione finora

- Us Vs ClarinDocumento2 pagineUs Vs Clarinjimart10Nessuna valutazione finora

- Bus Org CAse DigestDocumento18 pagineBus Org CAse DigestNovie FeneciosNessuna valutazione finora

- United States vs. ClarinDocumento3 pagineUnited States vs. ClarinChristine Gel MadrilejoNessuna valutazione finora

- GEORGE LITTON, Petitioner-Appellant, HILL & CERON, ET AL., Respondents-Appellees. G.R. No. L-45624 April 25, 1939Documento1 paginaGEORGE LITTON, Petitioner-Appellant, HILL & CERON, ET AL., Respondents-Appellees. G.R. No. L-45624 April 25, 1939Rio LorraineNessuna valutazione finora

- Litton v. HillDocumento2 pagineLitton v. HillMike Zaccahry MilcaNessuna valutazione finora

- US V Clarit - GR 5840 - Sep 17 1910Documento2 pagineUS V Clarit - GR 5840 - Sep 17 1910Jeremiah ReynaldoNessuna valutazione finora

- GR No 5840Documento2 pagineGR No 5840Carlo Lopez CantadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Plaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Defendant-Appellant Francisco Dominguez, Attorney-General VillamorDocumento2 paginePlaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Defendant-Appellant Francisco Dominguez, Attorney-General VillamorChristine Ang CaminadeNessuna valutazione finora

- Us V ClarinDocumento2 pagineUs V ClarinAyenGaileNessuna valutazione finora

- Us vs. Clarin 17 Phil 84 (1910), G.R. No. 5840, September 17, 1910Documento2 pagineUs vs. Clarin 17 Phil 84 (1910), G.R. No. 5840, September 17, 1910FranzMordenoNessuna valutazione finora

- 08 Litton V Hill & Ceron, GR No. L-45624, April 25, 1939 PDFDocumento7 pagine08 Litton V Hill & Ceron, GR No. L-45624, April 25, 1939 PDFMark Emmanuel LazatinNessuna valutazione finora

- US v. ClarinDocumento3 pagineUS v. ClarinMarinella ReyesNessuna valutazione finora

- Litton Vs Hill & Ceron Et AlDocumento2 pagineLitton Vs Hill & Ceron Et Alchisel_159Nessuna valutazione finora

- Litton v. Hill and CeronDocumento3 pagineLitton v. Hill and CeronkdescallarNessuna valutazione finora

- Delpher Trades Corp Vs Iac and Hydro Pipes IncDocumento5 pagineDelpher Trades Corp Vs Iac and Hydro Pipes IncAdrian HilarioNessuna valutazione finora

- Harden V Benguet Case DigestDocumento4 pagineHarden V Benguet Case DigestDeneb DoydoraNessuna valutazione finora

- G.R. No. 134559 December 9, 1999 ANTONIA TORRES Assisted by Her Husband, ANGELO TORRES and EMETERIA BARING Court of Appeals and Manuel Torres FactsDocumento3 pagineG.R. No. 134559 December 9, 1999 ANTONIA TORRES Assisted by Her Husband, ANGELO TORRES and EMETERIA BARING Court of Appeals and Manuel Torres FactsRio LorraineNessuna valutazione finora

- 41 US V ClarinDocumento1 pagina41 US V ClarinNichole LanuzaNessuna valutazione finora

- Article 1810-1814, Partnership (DIGEST)Documento2 pagineArticle 1810-1814, Partnership (DIGEST)Stephen Cabaltera100% (1)

- PARTNERSHIP - Case Digests From NetDocumento18 paginePARTNERSHIP - Case Digests From NetElizabeth Jade D. CalaorNessuna valutazione finora

- Doromal V CADocumento3 pagineDoromal V CAGertrude GamonnacNessuna valutazione finora

- PAT DigestDocumento7 paginePAT Digestjames oliverNessuna valutazione finora

- RobesDocumento7 pagineRobesGloria TrilloNessuna valutazione finora

- Litton Vs Hill and Ceron (DIGEST)Documento2 pagineLitton Vs Hill and Ceron (DIGEST)ckarla80100% (1)

- Partneship Cases 2Documento55 paginePartneship Cases 2Maria Yolly RiveraNessuna valutazione finora

- Partnershjip Digested CasesDocumento4 paginePartnershjip Digested CasesNurz A Tantong100% (1)

- CORP Lim Tong LimDocumento22 pagineCORP Lim Tong LimPatricia Jazmin PatricioNessuna valutazione finora

- Litton SingzonDocumento2 pagineLitton Singzonralph florence gomezNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Digest - GR No. 136448, 1999-11-03Documento3 pagineCase Digest - GR No. 136448, 1999-11-03Khalid Sharrif 0 SumaNessuna valutazione finora

- ARTICLE 1381 - Contracts Undertaken in Fraud of Creditors - Goquiolay vs. Sycip, 9 SCRA 663Documento3 pagineARTICLE 1381 - Contracts Undertaken in Fraud of Creditors - Goquiolay vs. Sycip, 9 SCRA 663Frances Tracy Carlos PasicolanNessuna valutazione finora

- Gozun Vs MercadoDocumento7 pagineGozun Vs MercadoVidar HalvorsenNessuna valutazione finora

- Partnership CaseDocumento4 paginePartnership CasejaneldeveraturdaNessuna valutazione finora

- Et Al. : G.R. No. 188417. September 24, 2012Documento3 pagineEt Al. : G.R. No. 188417. September 24, 2012bittersweetlemonsNessuna valutazione finora

- Lim Tong Lim V. Philippine Fishing Gear IndustriesDocumento7 pagineLim Tong Lim V. Philippine Fishing Gear IndustriesPeanutButter 'n JellyNessuna valutazione finora

- Tarlac State University Position PaperDocumento11 pagineTarlac State University Position PaperReymond Jude PagcoNessuna valutazione finora

- Partnership DoctrineDocumento6 paginePartnership DoctrineNoel Christopher G. BellezaNessuna valutazione finora

- Validity of ContractsDocumento14 pagineValidity of ContractsAref100% (1)

- 23 Lim Tong Lim, Petitioner, Vs - Philippine Fishing Gear Industries, IncDocumento1 pagina23 Lim Tong Lim, Petitioner, Vs - Philippine Fishing Gear Industries, IncMaria Cristina MartinezNessuna valutazione finora

- ANTONIA TORRES, Assisted by Her Husband, ANGELO TORRES and EMETERIA BARING, Petitioners, COURT OF APPEALS and MANUEL TORRES, Respondents. FactsDocumento4 pagineANTONIA TORRES, Assisted by Her Husband, ANGELO TORRES and EMETERIA BARING, Petitioners, COURT OF APPEALS and MANUEL TORRES, Respondents. FactsJohn Lloyd PerezNessuna valutazione finora

- Corporation DigestsDocumento15 pagineCorporation DigestsDeneb DoydoraNessuna valutazione finora

- Conde vs. Ca FactsDocumento8 pagineConde vs. Ca FactsasdfghjkattNessuna valutazione finora

- Agency and Partnership Digests #9Documento15 pagineAgency and Partnership Digests #9Janz SerranoNessuna valutazione finora

- Partnership Case DigestDocumento6 paginePartnership Case DigestTea AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- Partnership Digest EditedDocumento14 paginePartnership Digest EditedJovs TrivilegioNessuna valutazione finora

- 15 Lim v. Philippine Fishing Gear Industries, Inc., GR No. 136448, November, 1999 PDFDocumento12 pagine15 Lim v. Philippine Fishing Gear Industries, Inc., GR No. 136448, November, 1999 PDFMark Emmanuel LazatinNessuna valutazione finora

- Corpo 3Documento16 pagineCorpo 3Deneb DoydoraNessuna valutazione finora

- Partnership Cases DigestedDocumento6 paginePartnership Cases DigestedgretchengeraldeNessuna valutazione finora

- Cases - AgencyDocumento13 pagineCases - AgencyJoseph John Santos RonquilloNessuna valutazione finora

- 131 Litton V HillDocumento2 pagine131 Litton V HillChachi SorianoNessuna valutazione finora

- Union Rep Case DigestsDocumento2 pagineUnion Rep Case DigestsLourdes AngelieNessuna valutazione finora

- LabRel Lec 1Documento3 pagineLabRel Lec 1Lourdes AngelieNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Digest - Legend International Resorts Vs KMLDocumento2 pagineCase Digest - Legend International Resorts Vs KMLLourdes AngelieNessuna valutazione finora

- Republic Act No 10172Documento6 pagineRepublic Act No 10172Twinkle YsulatNessuna valutazione finora

- Ra 10607Documento4 pagineRa 10607Lourdes AngelieNessuna valutazione finora

- DAR Delisting For ARBDocumento9 pagineDAR Delisting For ARBLourdes Angelie100% (1)

- Transpo Digest COGSADocumento19 pagineTranspo Digest COGSALourdes AngelieNessuna valutazione finora

- Question PresentedDocumento1 paginaQuestion PresentedLourdes AngelieNessuna valutazione finora

- Consolidated Property Case Digests (1st Exam)Documento14 pagineConsolidated Property Case Digests (1st Exam)Lourdes Angelie100% (1)

- Ratio AnalysisDocumento25 pagineRatio Analysismba departmentNessuna valutazione finora

- SMC - All in 1Documento126 pagineSMC - All in 1Vitor ConsalterNessuna valutazione finora

- Inclusions To Gross Income Illustrative ExamplesDocumento5 pagineInclusions To Gross Income Illustrative ExamplesMary Rose CredoNessuna valutazione finora

- Rogue TraderDocumento10 pagineRogue TraderNehal VoraNessuna valutazione finora

- Financial Markets ReviewerDocumento21 pagineFinancial Markets ReviewerChristine RepuldaNessuna valutazione finora

- 23 Castillo V Balinghasay, GR No. 150976, October 18, 2004Documento11 pagine23 Castillo V Balinghasay, GR No. 150976, October 18, 2004Edgar Calzita AlotaNessuna valutazione finora

- Finantial Management - Ch4Documento142 pagineFinantial Management - Ch4댜라댠Nessuna valutazione finora

- Taxation ReviewerDocumento7 pagineTaxation ReviewerBusiness MatterNessuna valutazione finora

- Ch.1 Profit or Loss Pre and Post Incorporation - OrganizedDocumento14 pagineCh.1 Profit or Loss Pre and Post Incorporation - OrganizedMonikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Baobab Final Admission Doc Clean No CPRDocumento161 pagineBaobab Final Admission Doc Clean No CPRAbhishek Ranjan SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Business Correspondent AgreementDocumento13 pagineBusiness Correspondent AgreementAjay ChouhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Crim Pro SyllabusDocumento303 pagineCrim Pro SyllabusAling KinaiNessuna valutazione finora

- IAII FINAL EXAM Maual SET BDocumento9 pagineIAII FINAL EXAM Maual SET BClara MacallingNessuna valutazione finora

- Effect of Lease Financing On Corporate Performance of Deposit MONEY BANKS IN NIGERIA (2005-2016)Documento28 pagineEffect of Lease Financing On Corporate Performance of Deposit MONEY BANKS IN NIGERIA (2005-2016)aashir chNessuna valutazione finora

- China Mobile SolutionDocumento10 pagineChina Mobile Solutionnelsonpapa30% (1)

- CIMA Business PlanDocumento29 pagineCIMA Business PlanRonan NilandNessuna valutazione finora

- Ap02-01 Audit of SheDocumento6 pagineAp02-01 Audit of SheRenato OrosaNessuna valutazione finora

- Management AccountingDocumento2 pagineManagement AccountingkabilanNessuna valutazione finora

- MCQ in Engineering EconomicsDocumento318 pagineMCQ in Engineering EconomicsKen Joshua ManaloNessuna valutazione finora

- Lincoln Vs CA CIR DigestDocumento1 paginaLincoln Vs CA CIR DigestJay Ribs100% (1)

- Roc Forms & Secretarial PracticeDocumento11 pagineRoc Forms & Secretarial PracticeSankaran SwaminathanNessuna valutazione finora

- What Are Financial RatiosDocumento3 pagineWhat Are Financial RatiosChandria FordNessuna valutazione finora

- Leccture 4 - Cost of CapitalDocumento38 pagineLeccture 4 - Cost of CapitalSeth BrakoNessuna valutazione finora

- Interest Rates and Security ValuationDocumento19 pagineInterest Rates and Security ValuationHAZELMAE JEMINEZNessuna valutazione finora

- 3august - Grade 10 - 1st Quarter TestDocumento30 pagine3august - Grade 10 - 1st Quarter TestLucille Gacutan AramburoNessuna valutazione finora

- CH-5 Business CombinationsDocumento52 pagineCH-5 Business CombinationsRam KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Dec 2004 CS Executive AnswersDocumento74 pagineDec 2004 CS Executive Answersjesurajajoseph0% (1)

- Chapter 1 Fin 2200Documento7 pagineChapter 1 Fin 2200cheeseNessuna valutazione finora

- Indian Accounting Standards (One Pager)Documento29 pagineIndian Accounting Standards (One Pager)sridhartks100% (1)

- Derivatives (M) Assignment-1Documento3 pagineDerivatives (M) Assignment-1ShahbazNessuna valutazione finora