Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Transpo Cases (Lugue To KMU)

Caricato da

Leogen TomultoTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Transpo Cases (Lugue To KMU)

Caricato da

Leogen TomultoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

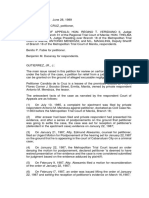

Luque v Villegas

Facts:

Petitioners ( who are passengers from Cavite and Batangas who ride on

buses to and from their province and Manila) and some public service

operators of buses and jeeps assail the validity of Ordinance 4986and

Administrative Order 1.

Ordinance 4986 states that PUB and PUJs shall be allowed to enter Manila

only from 6:30am to 8:30pm every day except Sundays and holidays.

Petitioners contend that since they possess a valid CPC, they have already

acquired a vested right to operate.

Administrative Order 1 issued by Commissioner of Public Service states that

all jeeps authorized to operate from Manila to any point in Luzon, beyond

the perimeter of Greater Manila, shall carry the words "For Provincial

Operation".

Issue: 1. Whether or not the said regulations are valid.

2. Whether or not Ordinance 4986 destroys vested rights to operate in

Manila.

Held: 1. YES! Using the doctrine in Lagman vs. City of Manila, Petitioner's

Certificate of Public Convenience was issued subject to the condition that

operators shall observe and comply with all the rules and regulations of the

PSC relative to PUB service.

The purpose of the ban is to minimize the problem in Manila and the traffic

congestion, delays and accidents resulting from the free entry into the

streets of Manila and the operation around said streets.

Both Ordinance 4986 and AO 1 fit into the concept of promotion and

regulation of general welfare.

2. NO! A vested right is some right or interest in the property which has

become fixed and established and is no longer open to doubt or

controversy. As far as the State is concerned, a CPC constitutes neither a

franchise nor a contract, confers no property right, and is a mere license or

privilege.

The holder does not acquire a property right in the route covered, nor does

it confer upon the holder any proprietary right/interest/franchise in the

public highways.

Neither do bus passengers have a vested right to be transported directly to

Manila. The alleged right is dependent upon the manner public services are

allowed to operate within a given area. It is no argument that the

passengers enjoyed the privilege of having been continuously transported

even before outbreak of war. Times have changed and vehicles have

increased. Traffic congestion has moved from worse to critical. Hence, there

is a need to regulate the operation of public services.

JG Summit Holdings Inc. vs. CA

G.R. No. 124293, November 20, 2000

FACTS:

The National Investment and Development Corporation (NIDC), a

government corporation, entered into a Joint Venture Agreement (JVA) with

Kawasaki Heavy Industries, Ltd. for the construction, operation and

management of the Subic National Shipyard, Inc., later became the

Philippine Shipyard and Engineering Corporation (PHILSECO). Under the JVA,

NIDC and Kawasaki would maintain a shareholding proportion of 60%-40%

and that the parties have the right of first refusal in case of a sale.

Through a series of transfers, NIDCs rights, title and interest in PHILSECO

eventually went to the National Government. In the interest of national

economy, it was decided that PHILSECO should be privatized by selling

87.67% of its total outstanding capital stock to private entities. After

negotiations, it was agreed that Kawasakis right of first refusal under the

JVA be exchanged for the right to top by five percent the highest bid for

said shares. Kawasaki that Philyards Holdings, Inc. (PHI), in which it was a

stockholder, would exercise this right in its stead.

During bidding, Kawasaki/PHI Consortium is the losing bidder. Even so,

because of the right to top by 5% percent the highest bid, it was able to top

JG Summits bid. JG Summit protested, contending that PHILSECO, as a

shipyard is a public utility and, hence, must observe the 60%-40% Filipino-

foreign capitalization. By buying 87.67% of PHILSECOs capital stock at

bidding, Kawasaki/PHI in effect now owns more than 40% of the stock.

ISSUE: Whether or not PHILSECO is a public utility

Whether or not Kawasaki/PHI can purchase beyond 40% of PHILSECOs

stocks

HELD: In arguing that PHILSECO, as a shipyard, was a public utility, JG

Summit relied on sec. 13, CA No. 146. On the other hand, Kawasaki/PHI

argued that PD No. 666 explicitly stated that a shipyard was not a public

utility. But the SC stated that sec. 1 of PD No. 666 was expressly repealed

by sec. 20, BP Blg. 391 and when BP Blg. 391 was subsequently repealed by

EO 226, the latter law did not revive sec. 1 of PD No. 666. Therefore, the law

that states that a shipyard is a public utility still stands.

A shipyard such as PHILSECO being a public utility as provided by law is

therefore required to comply with the 60%-40% capitalization under the

Constitution. Likewise, the JVA between NIDC and Kawasaki manifests an

intention of the parties to abide by this constitutional mandate. Thus, under

the JVA, should the NIDC opt to sell its shares of stock to a third party,

Kawasaki could only exercise its right of first refusal to the extent that its

total shares of stock would not exceed 40% of the entire shares of stock.

The NIDC, on the other hand, may purchase even beyond 60% of the total

shares. As a government corporation and necessarily a 100% Filipino-owned

corporation, there is nothing to prevent its purchase of stocks even beyond

60% of the capitalization as the Constitution clearly limits only foreign

capitalization.

Kawasaki was bound by its contractual obligation under the JVA that limits

its right of first refusal to 40% of the total capitalization of PHILSECO. Thus,

Kawasaki cannot purchase beyond 40% of the capitalization of the joint

venture on account of both constitutional and contractual proscriptions.

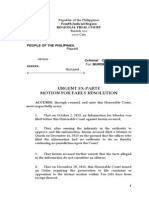

KILUSANG MAYO UNO LABOR CENTER vs.HON. JESUS B. GARCIA, JR., the

LAND TRANSPORTATION FRANCHISING AND REGULATORY BOARD, and

the PROVINCIAL BUS OPERATORS ASSOCIATION OF THE PHILIPPINES G.R.

No. 115381 December 23, 1994

FACTS :

Then Secretary of DOTC, Oscar M. Orbos, issued Memorandum Circular No.

90-395 to then LTFRB Chairman, Remedios A.S. Fernando allowing provincial

bus operators to charge passengers rates within a range of 15% above and

15% below the LTFRB official rate for a period of one (1) year.

This range was later increased by LTFRB thru a Memorandum Circular No.

92-009 providing, among others, that "The existing authorized fare range

system of plus or minus 15 per cent for provincial buses and jeepneys shall

be widened to 20% and -25% limit in 1994 with the authorized fare to be

replaced by an indicative or reference rate as the basis for the expanded

fare range."

Sometime in March, 1994, private respondent PBOAP, availing itself of the

deregulation policy of the DOTC allowing provincial bus operators to collect

plus 20% and minus 25% of the prescribed fare without first having filed a

petition for the purpose and without the benefit of a public hearing,

announced a fare increase of twenty (20%) percent of the existing fares.

On March 16, 1994, petitioner KMU filed a petition before the LTFRB

opposing the upward adjustment of bus fares, which the LTFRB dismissed

for lack of merit.

ISSUE: Whether or not the authority given by respondent LTFRB to

provincial bus operators to set a fare range of plus or minus fifteen (15%)

percent, later increased to plus twenty (20%) and minus twenty-five (-25%)

percent, over and above the existing authorized fare without having to file a

petition for the purpose, is unconstitutional, invalid and illegal.

HELD: Yes. Under section 16(c) of the Public Service Act, the Legislature

delegated to the defunct Public Service Commission the power of fixing the

rates of public services. Respondent LTFRB, the existing regulatory body

today, is likewise vested with the same under Executive Order No. 202

dated June 19, 1987. x x x However, nowhere under the aforesaid provisions

of law are the regulatory bodies, the PSC and LTFRB alike, authorized to

delegate that power to a common carrier, a transport operator, or other

public service.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- GR 225669 2022Documento14 pagineGR 225669 2022Leogen TomultoNessuna valutazione finora

- G.R. No. 164961 June 30, 2014Documento15 pagineG.R. No. 164961 June 30, 2014Leogen TomultoNessuna valutazione finora

- NUGUID v. CARIÑODocumento3 pagineNUGUID v. CARIÑOLeogen TomultoNessuna valutazione finora

- Articles of Partnership SampleDocumento3 pagineArticles of Partnership SampleLeogen TomultoNessuna valutazione finora

- Cruz Vs CaDocumento5 pagineCruz Vs CaLeogen TomultoNessuna valutazione finora

- Cruz Vs CaDocumento5 pagineCruz Vs CaLeogen TomultoNessuna valutazione finora

- Rules on legal inheritanceDocumento2 pagineRules on legal inheritanceyurets929Nessuna valutazione finora

- A.C. No. 6422 August 28, 2007Documento4 pagineA.C. No. 6422 August 28, 2007Leogen TomultoNessuna valutazione finora

- A.C. No. 6422 August 28, 2007Documento4 pagineA.C. No. 6422 August 28, 2007Leogen TomultoNessuna valutazione finora

- Primary Responsibilities of A Human Resource ManagerDocumento2 paginePrimary Responsibilities of A Human Resource ManagerLeogen TomultoNessuna valutazione finora

- Torrent Downloaded FromDocumento1 paginaTorrent Downloaded FromAhmad RonyNessuna valutazione finora

- Rebusquillo v. DomingoDocumento6 pagineRebusquillo v. DomingoLeogen TomultoNessuna valutazione finora

- People Vs SungaDocumento15 paginePeople Vs SungaLeogen TomultoNessuna valutazione finora

- Rebusquillo v. DomingoDocumento6 pagineRebusquillo v. DomingoLeogen TomultoNessuna valutazione finora

- Juris On - Change of Date (Formal Amendment)Documento4 pagineJuris On - Change of Date (Formal Amendment)Leogen TomultoNessuna valutazione finora

- Basic legal forms captionsDocumento44 pagineBasic legal forms captionsDan ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- People Vs SungaDocumento15 paginePeople Vs SungaLeogen TomultoNessuna valutazione finora

- Ben ShapiroDocumento11 pagineBen ShapiroLeogen Tomulto100% (1)

- JurisDocumento2 pagineJurisLeogen TomultoNessuna valutazione finora

- People Vs SungaDocumento15 paginePeople Vs SungaLeogen TomultoNessuna valutazione finora

- ADMINISTRATIVE CIRCULAR NO. 4 September 22, 1988Documento3 pagineADMINISTRATIVE CIRCULAR NO. 4 September 22, 1988Leogen TomultoNessuna valutazione finora

- RR 18-01Documento7 pagineRR 18-01JvsticeNickNessuna valutazione finora

- Annex B-1 RR 11-2018 Sworn Statement of Declaration of Gross Sales and ReceiptsDocumento1 paginaAnnex B-1 RR 11-2018 Sworn Statement of Declaration of Gross Sales and ReceiptsEliza Corpuz Gadon89% (19)

- 3 RR 6-2001 PDFDocumento17 pagine3 RR 6-2001 PDFJoyceNessuna valutazione finora

- Drilon v. CaDocumento13 pagineDrilon v. CaLeogen TomultoNessuna valutazione finora

- COMELEC ruling on 2010 Barangay elections in Lanao del NorteDocumento8 pagineCOMELEC ruling on 2010 Barangay elections in Lanao del NorteCyber QuestNessuna valutazione finora

- Revenue Regulations 02-03Documento22 pagineRevenue Regulations 02-03Anonymous HIBt2h6z7Nessuna valutazione finora

- Republic of The Philippines, Local Civil Registrar of Cauayan, PetitionersDocumento4 pagineRepublic of The Philippines, Local Civil Registrar of Cauayan, PetitionersLeogen Tomulto100% (1)

- Philippines Murder Case MotionDocumento2 paginePhilippines Murder Case MotionMark Agustin100% (6)

- Roxas and Co Vs CA and DarDocumento69 pagineRoxas and Co Vs CA and DarChaNessuna valutazione finora

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Burgos v. Aquino (Digest)Documento2 pagineBurgos v. Aquino (Digest)Patrick DamasoNessuna valutazione finora

- Application For Subsequent Release of Educational Assistance LoanDocumento2 pagineApplication For Subsequent Release of Educational Assistance LoanNikkiQuiranteNessuna valutazione finora

- UPSC Mains Worksheets: Indian PolityDocumento10 pagineUPSC Mains Worksheets: Indian PolityAditya Kumar SingareNessuna valutazione finora

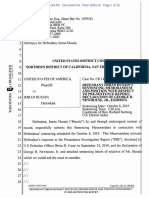

- Imran Husain Sentencing Memo Oct 2019Documento15 pagineImran Husain Sentencing Memo Oct 2019Teri BuhlNessuna valutazione finora

- NM Civil Guard Filed Verified ComplaintDocumento39 pagineNM Civil Guard Filed Verified ComplaintAlbuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- 121-160 JurisprudenceDocumento44 pagine121-160 JurisprudencejilliankadNessuna valutazione finora

- 07 GR 211721Documento11 pagine07 GR 211721Ronnie Garcia Del RosarioNessuna valutazione finora

- Class Topic: Political Question G.R. No. 196231 January 28, 2014Documento2 pagineClass Topic: Political Question G.R. No. 196231 January 28, 2014DEAN JASPERNessuna valutazione finora

- Bhutto & Zardari's Corruption Highlighted in Raymond Baker's Book On Dirty Money - Teeth MaestroDocumento6 pagineBhutto & Zardari's Corruption Highlighted in Raymond Baker's Book On Dirty Money - Teeth Maestroسید ہارون حیدر گیلانیNessuna valutazione finora

- Yapyuco Vs Sandiganbayan 674 Scra 420Documento4 pagineYapyuco Vs Sandiganbayan 674 Scra 420Cecille Bautista100% (2)

- Supreme Court Ruling on Employer Liability for Acts of EmployeesDocumento7 pagineSupreme Court Ruling on Employer Liability for Acts of EmployeesAj SobrevegaNessuna valutazione finora

- Regeln Biblothek ENDocumento2 pagineRegeln Biblothek ENMarta AlmeidaNessuna valutazione finora

- Compliance of Citizenship Requirement For Application of CPF GrantDocumento2 pagineCompliance of Citizenship Requirement For Application of CPF GrantSGExecCondosNessuna valutazione finora

- Microsoft Collaborate Terms of UseDocumento6 pagineMicrosoft Collaborate Terms of UseZeeshan OpelNessuna valutazione finora

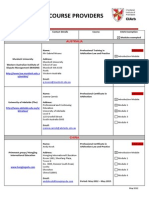

- Recognised Course Providers ListDocumento13 pagineRecognised Course Providers ListSo LokNessuna valutazione finora

- General (Plenary) Legislative PowerDocumento162 pagineGeneral (Plenary) Legislative PowerBrenda de la GenteNessuna valutazione finora

- Fin e 328 2017Documento5 pagineFin e 328 2017division4 designsNessuna valutazione finora

- United States v. Vincent Gigante, Vittorio Amuso, Venero Mangano, Benedetto Aloi, Peter Gotti, Dominic Canterino, Peter Chiodo, Joseph Zito, Dennis Delucia, Caesar Gurino, Vincent Ricciardo, Joseph Marion, John Morrissey, Thomas McGowan Victor Sololewski, Anthony B. Laino, Gerald Costabile, Andre Campanella, Michael Realmuto, Richard Pagliarulo, Michael Desantis, Michael Spinelli, Thomas Carew, Corrado Marino, Anthony Casso, 187 F.3d 261, 2d Cir. (1999)Documento4 pagineUnited States v. Vincent Gigante, Vittorio Amuso, Venero Mangano, Benedetto Aloi, Peter Gotti, Dominic Canterino, Peter Chiodo, Joseph Zito, Dennis Delucia, Caesar Gurino, Vincent Ricciardo, Joseph Marion, John Morrissey, Thomas McGowan Victor Sololewski, Anthony B. Laino, Gerald Costabile, Andre Campanella, Michael Realmuto, Richard Pagliarulo, Michael Desantis, Michael Spinelli, Thomas Carew, Corrado Marino, Anthony Casso, 187 F.3d 261, 2d Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- ERA1209-003 Clarification About Responsibilities For Populating ERADISDocumento7 pagineERA1209-003 Clarification About Responsibilities For Populating ERADISStan ValiNessuna valutazione finora

- 5.4 Arrests Press ReleasesDocumento4 pagine5.4 Arrests Press Releasesnpdfacebook7299Nessuna valutazione finora

- Citibank V.dinopol, GR 188412Documento7 pagineCitibank V.dinopol, GR 188412vylletteNessuna valutazione finora

- Thinking Like A Lawyer - An Introduction To Legal Reasoning (PDFDrive)Documento349 pagineThinking Like A Lawyer - An Introduction To Legal Reasoning (PDFDrive)Financial Unit MIMAROPANessuna valutazione finora

- PFR-Franklin Baker Vs AlillanaDocumento5 paginePFR-Franklin Baker Vs Alillanabam112190Nessuna valutazione finora

- Salient provisions of new anti-terrorism law and repeal of HSADocumento18 pagineSalient provisions of new anti-terrorism law and repeal of HSAJayson Tababan50% (2)

- Mercado V AMA - April 13, 2010 - LaborDocumento18 pagineMercado V AMA - April 13, 2010 - LaborStGabrielleNessuna valutazione finora

- Income Taxation NotesDocumento45 pagineIncome Taxation NotesIlonah HizonNessuna valutazione finora

- The Real NotesDocumento33 pagineThe Real NotesKarlo KapunanNessuna valutazione finora

- Final Audit Document - Opsa Audit Report - SPD Complaint Case Audit Improper Search and Seizure 2023Documento34 pagineFinal Audit Document - Opsa Audit Report - SPD Complaint Case Audit Improper Search and Seizure 2023CBS13Nessuna valutazione finora

- EPacific Vs CabansayDocumento2 pagineEPacific Vs CabansayStephanie Valentine100% (1)

- IPC Nov 2019Documento21 pagineIPC Nov 2019adiNessuna valutazione finora