Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Transsexual Emergence Gender Variant Identities in Thailand

Caricato da

juaromerDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Transsexual Emergence Gender Variant Identities in Thailand

Caricato da

juaromerCopyright:

Formati disponibili

SHORT REPORT

Transsexual emergence: gender variant identities in Thailand

Witchayanee Ocha*

Gender and Development Studies, Asian Institute of Technology, Pathumthani, Thailand

(Received 23 August 2011; nal version received 1 March 2012)

This paper aims to contribute to understanding of emergent gender/sexual identities in

Thailand. Thailand has become a popular destination for sex change operations by

providing the medical technology for a complete transformation, with relatively few

procedures and satisfactory results at a reasonable price. Data were gathered from 24

transsexual male-to-female sex workers working in Pattaya and Patpong, well-known

sex-tourism hot spots in Thailand. Findings suggest the emergence of new

understandings of gender/sexual identity. Sex-tourism/sex work signicantly illumi-

nates the process through which gender is contested and re-imagined. The coming

together of cultures in Thailands sex industry, coupled with advances in medical

technology, has resulted in the emergence of new concepts of gender.

Keywords: sexualities; sex reassignment surgery; transgender; sex tourism; Thailand

Introduction

Recent transgender scholarship (Roen 2006; Towle and Morgan 2006) has bemoaned the

shallow and reductive portrayal in the US media of gender-liminal people in non-Western

societies. Towle and Morgan (2006) note that Euro-American transgender activists

frequently invoke the ubiquity of non-Western third-gender people to prove transgender

universality and thereby bolster transgender legitimacy. In so doing, they conate third

gender with transgender when in fact they are not the same.

The Western term transgender assumes a gender binary people may change genders

but they have not historically been considered a third gender (Lorber 1996). In contrast, in

some cultures, a third-gender category has always existed alongside the categories of

men and women. The third gender is neither male nor female even though the persons

genitals may be readily classiable. Use of the term transgender in reference to those

cultures reduces three sexes to two. Further complicating the cross-cultural terrain is the

terminology of modern medical technology. People in the third-gender category are able

to change their bodies, but sex reassignment refers to changing sexes as understood in the

West semantically, three are again reduced to two.

The inherent problems of cross-cultural analysis are signicant and many. Language is

an expression of culture and is a reection of different forms of knowledge. Though

diverse, Thai identities will be explored in this paper. The author uses the terms

transgender and transsexual, even though they are inadequate for three-gender societies.

Transgender refers to anatomically male people who identify themselves as third-gender

ISSN 1369-1058 print/ISSN 1464-5351 online

q 2012 Taylor & Francis

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2012.672653

http://www.tandfonline.com

*Email: witchayaneeocha@gmail.com

Culture, Health & Sexuality

Vol. 14, No. 5, May 2012, 563575

people and live as women but who have not undergone sex reassignment surgery.

Becoming transsexual implies engagement with medical institutions to access the

hormonal and surgical technologies needed for embodying ones internal identity (Stryker

1994). In this study, the term transsexual refers to third-gender individuals who have

undergone complete male to female (MTF) anatomical transformation.

Homosexuality is not a well-recognised or often used category in popular Thai

discourse (Sinnott 2000, 425). Presently, there is no commonly accepted Thai equivalent

for the English term transpeople (Winter 2011, 252). In Thailand, the most common

word for transgender is kathoey. Originally used to describe hermaphrodites, this term was

also used to refer to female-bodied individuals who are perceived as masculine (FTM) as

well as any male contravening gender role expectations (homosexual and effeminate

males etc.) (Winter 2002, 14). However, the term kathoey later came to encompass

only MTF transgenders. This paper focuses on the gender/sexual identities of MTF

transgenders because they are the most prevalent in Thailands sex tourism industry.

Jackson (2011) has drawn attention to Bangkoks emergence as a central focus of

an expanding regional network linking gender variant communities in Hong Kong,

Singapore, Taiwan, Indonesia, the Philippines and other rapidly developing East and

Southeast Asiansocieties (inside cover). In Thailand, the sexsector is animportant source of

emergent sexualities and is also a productive environment for studying gender. Transsexual

MTF sex workers are the most visible faces of these diversied forms that are emerging and

that reect the Buddhist concept of anatta (non-self) and anicca (impermanence).

This paper suggests that the global sex industrys impact as a signicant source of new

sexual and gender expressions can contribute to an understanding of the more complex

concept of gender. I focus on two aspects of the identity question: (1) power, resistance

and self-image development through the sex industry and (2) bodies subjectivity and

embodiment before and after a sex change operation. Evidence from the eldwork

suggests that the sex industry is not only driving a uidity of sexuality among sex workers

but is one of the factors responsible for the creation of new gender/sexual identities. The

research shows that medical technology and the ability of sex workers to earn money by

using their transformed bodies in the sex industry permits a wide range of performance

and, consequently, a wide array of gender identities. Finally, it is concluded that the

coming together of cultures in Thailands sex industry, coupled with the advances in

medical technology in changing gender identity through surgery, has resulted in the

emergence of new concepts of gender.

Gender identity disorder

From a medical perspective, transgenderism is sometimes considered a gender identity

disorder (Tiewtranon and Chokrungvaranont 2004). It presents when there is strong

ongoing cross-gender identication, that is, a desire to live and be accepted as a member of

the opposite sex. Medical doctors believe that transgender people have persistent

discomfort with their natural anatomical sex and feel inappropriate in their gender roles.

These feelings are often accompanied by a wish to have hormonal treatment and surgery

that will make the body congruent with the self-image.

Sex reassignment surgery (SRS) to change the body to t the self-image was

established in 1975 in Thailand (Tiewtranon and Chokrungvaranont 2004). Aizura (2011)

has pointed out that Thailand is now known by many as one of the premier sites

worldwide to obtain vaginoplasty and other cosmetic surgeries; indeed, many surgeons

advertise Bangkok as the Mecca of transsexual body modication (144), while Winter

564 W. Ocha

(2004) says that, Thailand probably boasts one of the highest incidences of transgenders

worldwide. No one knows for sure how many transgenders there are, but the gures range

from 10,000 to 300,000. Even the lowest of these gures would put the incidence way

above Western countries (7). Although the exact numbers for the transgender population

are elusive, the estimated ratio of transgenders to straight men is 1:30,000 (Bunyanathee

and Piyyopornpanit 1999, 324). However, this paper suggests that these gures are a gross

underestimate. Presently, Thailand is a popular place for sex change operations not only

for Thais but also for foreigners, because there are many clinics that produce satisfactory

results and are less expensive than in the West (Totman 2003).

Thailand has a rich, indigenous history of complex patterns of sexuality and gender.

Historically, an intermediate category, the third sex/gender, kathoey; phet-thi-sam, has

been recognised for both males and females and has existed alongside normative masculine

and feminine identities (Jackson and Sullivan 2000, 3). The terms portray the MTF third

gender as either a subset of female or an entirely different gender (Winter 2005, 3).

Indeed, a single word, phet, denotes both sex and gender which undermines

attempts to translate English terms such as transgender and transsexual (Winter 2011,

252). Van Esterik (2000) explains that gender identity in Thai culture is body-based and

starts with a notion of the embodied self that is rooted in material and physiological

conditions. The Thai gender system is best represented as a continuum with permeable

boundaries, a systemthat is not primarily binary, thus allowing space for a third sex/gender.

What is stressed in the Thai system is the ability of people to move in and out of categories

according to context, allowing the ow and co-existence of multiple gender identities.

Schrock, Reid and Boyd (2005) emphasise that bodies be our friends or enemies, a

source of pain or pleasure, a place of liberation or domination, but they are also the

material with which we experience and create gender (317). Namaste (2000) and Rubin

(2003) also move transgender scholarship toward understanding the link between bodies

and subjectivities. Namaste analysed the coping mechanisms of transsexuals towards

violations and threats to their bodies from police and discriminatory health care providers

(Valocchi 2005, 766). Rubin (2003) examined FTM transsexuals experiences of feeling

betrayed by their birth bodies and their experiences and feelings as they grow into their

male bodies. Schrock, Reid and Boyd (2005) drew on the concept of an essential

connection between body and self through a sample of transsexuals who reported that

feelings of authenticity increased when their outer appearance and behavior were aligned

with their inner denition of self. The authors explain that the informants understanding

of identity and their success in assuming womanhood were thoroughly body-based.

Foremost queer theorist Judith Butler (1990) proposed the idea of free-oating

identities that are not connected to an essence but, instead, to performance. She argues,

controversially, that feminism works against its explicit aims by requiring that certain

kinds of identities in which gender does not follow from sex and those in which the

practices of desire do not follow from either sex or gender (17). This structuralist-

essentialist debate is relevant to the Thai case, where the core gender identities,

embodiments and preferred sexual practices of sex workers are mutable and may not t

specic denitions of gender categories.

Grzelinska (2012, 113) has written that queer theory has been doing exciting things with

methodologies for over 20 years now.

1

Valocchi (2005) urges greater attention to

practices (767) as having the potential to reveal individuals inner thinking, values and

desires that comprise their identities. Gahan (2012) has documented that the experiences

of gender variant people conrm the presence and existence of sexual minorities, even

in spaces where their existence is most contested and oppressed. To date, there has been

Culture, Health & Sexuality 565

a growingrecognitionof the complexrelationshipbetweenculture andpower, andincreasing

attention to the political and economic dimension of sexuality (Parker 2009, 251).

Thailands sex tourism industry

Thailand is often described as the sex tourist destination (Gallagher 2005, 4). Though this

remains a valid viewpoint, the nature of that sex has begun to shift dramatically in recent

years because of an increasing number of transgender (kathoey) sex workers. Gallagher

stated that two salient trends in particular have emerged in the sex tourism industry: the

growing heterogeneity of sex tourists and the variety of sex workers and sexual-economic

exchanges. Tourism campaigns often promote Thailand as exotic and erotic in an

attempt to attract tourists. The sex industry appears to be drawn to Thailand as a place

where emerging sexual forms can ourish and feel welcome. Sex tourism stabilises and

fosters the creation of new gender identities that are becoming more visible in the sex

industry in contemporary Thailand. The globalisation of the sex trade is legitimised by the

developed worlds encouragement of Asia as a key tourism centre (Kuo 2000, 2). Tourism

has become a signicant strategy for development in Thailand and has had a crucial impact

on the sex trade that shapes the notion of gender/sexual identities. Sex change operations

have been prominent in the global media, which has played an important role in promoting

new gender/sexual identities in Thai society.

Research and methodology

The ethnographic eldwork in this study involved Thai MTF transsexual sex workers

engaged in direct and indirect sex for hire in Thailands sex tourism industry. Almost all

the qualitative data were collected during in-depth interviews of 25 Thai transsexual sex

workers.

2

Fieldwork was conducted in Pattaya and Patpong, well-known sex-tourism hot

spots over a six-month period in 2006 (three months in each location) and followed up in

2009 (one month in each location). The interviews took place at host bars (those that

offered no special shows and had no entrance fees), go-go bars (which provide live shows

for which customers have to pay an entrance fee) and cabaret theatres in which lip synch

shows are popular.

Respondents were interviewed in Thai off stage. They were encouraged to speak about

their identities and self-images. Each respondent had more than a year of experience in the

sex tourism industry. I asked their permission and recorded and analysed their replies.

3

Later, I returned to allow the respondents to review the results and conclusions. The names

mentioned in this paper are pseudonyms, which were used to protect the identities of the

respondents.

This paper interprets gender/sexual identities and performance by how the respondents

view their own identities rather than how other people view them. The scope of this study

was limited by the fact that the respondents were engaged in illegal activities. A number of

respondents needed to be guaranteed anonymity, but the number was limited by the

discretion required to nd, select and interview them and the strict condentiality with

which all participation and information was obtained.

Findings

Male-to-female transsexual sex workers

A total of 24 transsexual sex worker informants, ranging in age from 1737 years,

participated in the study. All were working full time: 14 were entertainers/artistes in the

566 W. Ocha

cabarets, 4 were working in host bars and 6 were working in go-go bars. The respondents

came from all over the country, but the modal value consisted of 10 who came from a poor

northeastern region known as Isaan. Nine had high school education, while the majority

quit school at grade nine or lower. All but two reported their level of family nancial

security as low, with two reporting medium. All sent money home on a monthly basis

in amounts ranging from 2,000 to 5,000 baht

4

. From a Thai cultural perspective, Thai

transsexuals may buy the right to sexual and gender autonomy within their families by

providing nancial support. Such personal wealth can be used to buy a space for queer

sexual autonomy within a heteronormative culture wherein family ties remain central to

queer identity and sense of self-worth (Ocha 2008, as cited in Jackson 2011, 202).

All informants reported early feelings (between the ages of 4 and 13) of being at odds

with their male gender but had different ways of describing these feelings. In all, 13 had

the inner realisation that they were phu-ying, that is, that they were really girls, 7 felt they

were neither male nor female, while 4 felt they were really kathoey (Table 1).

Although always knowing they were different, they did not hide their identities and

enjoyed friendships as members of a third gender. As students they had to wear boys

uniforms, but they could express themselves through make-up, hairstyles, accessories and

gender-bending behaviour. Interpersonally, being of a third gender is open and acceptable

in Thailand, especially as a young person, but there is no third-gender legal status. Thus,

upon reaching adulthood, life becomes problematic because they no longer t easily into

conventional society. Even though they were live as women in every way, their legal

documentation classies them as male, causing problems in some employment sectors and

sometimes subjecting them to service in the armed forces. This mist status, in a sense,

seals their marginality and is a factor pushing them to work in the sex industry.

Identity prior to surgery

Like the transsexual informants reported in Namaste (2000), Rubin (2003) and Schrock

et al. (2005), the respondents felt they had core inner identities that differed from their

male gender. However, unlike Western transsexuals, who almost always feel that they are

women born in mens bodies (Schrock et al. 2005), informants reported three different

identities. The 13 who identied as phu-ying (women) lived pre-operatively as women

with perfectly feminine dress and appearance at all times. Being phu-ying meant they were

attracted to straight men (gender-normative men). Before vaginoplasty, all of them liked to

be the receptive partner in anal sex with straight men (Table 1).

The seven informants who early in life had felt that they were neither male nor female

reported living pre-operatively as phu-chai (men). They wore mens clothing and had

masculine identities in public. In private, however, they dressed as women, associated

with other third genders and were open about their confused identities. At the time of the

interviews, they had been taking female hormones for at least two years. Five preferred

anal sex with gay men, while two were receptive to both anal sex with gay men and

insertive vaginal intercourse with straight women (Table 1).

Four informants reported living pre-operatively as kathoey (third gender). This means

that they had a third-gender identity, but not in the same sense as phu-ying (women).

Whereas phu-ying were attracted to straight men, the phu-chai and kathoey liked to be the

receptive partner during anal sex with gay men (Table 1). All of the identities incorporated

a relational aspect: their identities included references to their preferred sexual partners.

The body is the means for engaging the world. The author agrees with Valocchi (2005)

that practices (in this case, preferred activities, preferred partners and activities considered

Culture, Health & Sexuality 567

T

a

b

l

e

1

.

T

r

a

n

s

s

e

x

u

a

l

s

e

x

w

o

r

k

e

r

s

r

e

p

o

r

t

e

d

i

d

e

n

t

i

t

i

e

s

b

e

f

o

r

e

a

n

d

a

f

t

e

r

s

u

r

g

i

c

a

l

t

r

a

n

s

f

o

r

m

a

t

i

o

n

(

n

2

4

)

.

I

n

n

e

r

i

d

e

n

t

i

t

y

b

e

f

o

r

e

s

u

r

g

e

r

y

G

e

n

d

e

r

p

r

e

s

e

n

t

a

t

i

o

n

b

e

f

o

r

e

s

u

r

g

e

r

y

P

r

e

f

e

r

r

e

d

s

e

x

-

u

a

l

a

c

t

i

v

i

t

i

e

s

b

e

f

o

r

e

s

u

r

g

e

r

y

P

r

e

f

e

r

r

e

d

s

e

x

u

a

l

p

a

r

t

n

e

r

(

s

)

b

e

f

o

r

e

s

u

r

g

e

r

y

I

n

n

e

r

i

d

e

n

t

i

t

y

a

f

t

e

r

s

u

r

g

e

r

y

G

e

n

d

e

r

p

r

e

s

e

n

t

a

t

i

o

n

a

f

t

e

r

s

u

r

g

e

r

y

P

r

e

f

e

r

r

e

d

s

e

x

u

a

l

a

c

t

i

v

i

t

i

e

s

a

f

t

e

r

s

u

r

g

e

r

y

P

r

e

f

e

r

r

e

d

s

e

x

u

a

l

p

a

r

t

n

e

r

(

s

)

a

f

t

e

r

s

u

r

g

e

r

y

R

e

f

u

s

e

t

h

e

s

e

s

e

x

u

a

l

a

c

t

i

v

i

t

i

e

s

a

f

t

e

r

s

u

r

g

e

r

y

S

a

t

i

s

e

d

w

i

t

h

s

u

r

g

i

c

a

l

t

r

a

n

s

f

o

r

m

a

t

i

o

n

(

n

)

(

n

)

(

n

)

(

n

)

(

n

)

(

n

)

(

n

)

(

n

)

(

n

)

(

n

)

P

h

u

-

y

i

n

g

S

o

l

d

s

e

x

a

s

a

p

h

u

-

y

i

n

g

(

1

3

)

P

h

u

-

y

i

n

g

;

f

e

m

i

n

i

n

e

c

l

o

t

h

e

s

;

f

e

m

i

n

i

n

e

i

d

e

n

t

i

t

y

a

t

a

l

l

t

i

m

e

s

(

1

3

)

R

e

c

e

p

t

i

v

e

a

n

a

l

s

e

x

(

1

3

)

S

t

r

a

i

g

h

t

m

e

n

(

1

3

)

P

h

u

-

y

i

n

g

(

7

)

W

o

m

a

n

i

n

p

u

b

l

i

c

b

u

t

o

f

f

e

r

e

d

t

r

a

n

s

s

e

x

u

a

l

s

e

x

(

4

)

R

e

c

e

p

t

i

v

e

v

a

g

i

n

a

l

s

e

x

(

7

)

S

t

r

a

i

g

h

t

m

e

n

(

7

)

L

e

s

b

i

a

n

s

e

x

(

6

)

Y

e

s

(

6

)

S

a

o

p

r

a

p

h

e

t

s

o

r

n

g

(

6

)

S

a

o

p

r

a

p

h

e

t

s

o

r

n

g

i

n

p

u

b

l

i

c

;

o

f

f

e

r

e

d

t

r

a

n

s

s

e

x

u

a

l

s

e

x

(

3

)

R

e

c

e

p

t

i

v

e

v

a

g

i

n

a

l

s

e

x

(

6

)

S

t

r

a

i

g

h

t

m

e

n

(

6

)

R

e

c

e

p

t

i

v

e

a

n

a

l

s

e

x

(

4

)

P

a

r

t

i

a

l

l

y

(

1

)

S

a

o

p

r

a

p

h

e

t

s

o

r

n

g

i

n

p

u

b

l

i

c

;

o

f

f

e

r

e

d

t

r

a

n

s

s

e

x

u

a

l

s

e

x

(

6

)

L

e

s

b

i

a

n

s

e

x

(

1

)

P

a

r

t

i

a

l

l

y

(

4

)

N

o

(

2

)

P

h

u

-

c

h

a

i

i

n

t

r

a

n

s

i

t

i

o

n

,

(

7

)

P

h

u

-

c

h

a

i

;

M

a

l

e

c

l

o

t

h

e

s

;

m

a

s

c

u

l

i

n

e

i

d

e

n

t

i

t

y

i

n

p

u

b

l

i

c

.

I

n

p

r

i

v

a

t

e

,

d

r

e

s

s

e

d

a

s

w

o

m

e

n

,

h

u

n

g

o

u

t

w

i

t

h

t

r

a

n

s

p

e

o

p

l

e

(

7

)

R

e

c

e

p

t

i

v

e

a

n

a

l

s

e

x

(

5

)

G

a

y

m

e

n

(

5

)

S

a

o

p

r

a

p

h

e

t

s

o

r

n

g

(

4

)

S

a

o

p

r

a

p

h

e

t

s

o

r

n

g

i

n

p

u

b

l

i

c

;

o

f

f

e

r

e

d

t

r

a

n

s

s

e

x

u

a

l

s

e

x

(

4

)

R

e

c

e

p

t

i

v

e

v

a

g

i

n

a

l

s

e

x

(

4

)

S

t

r

a

i

g

h

t

m

e

n

(

4

)

N

o

n

e

(

7

)

Y

e

s

(

1

)

P

a

r

t

i

a

l

l

y

(

2

)

N

o

(

1

)

P

e

n

e

t

r

a

t

i

v

e

v

a

g

i

n

a

l

s

e

x

a

n

d

r

e

c

e

p

t

i

v

e

a

n

a

l

s

e

x

(

2

)

B

o

t

h

s

t

r

a

i

g

h

t

w

o

m

e

n

a

n

d

g

a

y

m

e

n

(

2

)

K

a

t

h

o

e

y

(

1

)

S

a

o

p

r

a

p

h

e

t

s

o

r

n

g

i

n

p

u

b

l

i

c

;

o

f

f

e

r

e

d

t

r

a

n

s

s

e

x

u

a

l

s

e

x

(

1

)

B

o

t

h

r

e

c

e

p

t

i

v

e

v

a

g

i

n

a

l

s

e

x

a

n

d

r

e

c

e

p

t

i

v

e

a

n

a

l

s

e

x

(

1

)

P

a

r

t

n

e

r

s

b

o

t

h

s

t

r

a

i

g

h

t

m

e

n

a

n

d

g

a

y

m

e

n

(

1

)

P

a

r

t

i

a

l

l

y

(

2

)

D

o

n

t

k

n

o

w

(

2

)

S

a

o

p

r

a

p

h

e

t

s

o

r

n

g

i

n

p

u

b

l

i

c

;

o

f

f

e

r

e

d

t

r

a

n

s

s

e

x

u

a

l

s

e

x

(

2

)

R

e

c

e

p

t

i

v

e

v

a

g

i

n

a

l

s

e

x

a

n

d

l

e

s

b

i

a

n

s

e

x

(

p

a

s

s

i

v

e

r

o

l

e

)

(

2

)

P

a

r

t

n

e

r

s

b

o

t

h

s

t

r

a

i

g

h

t

m

e

n

a

n

d

t

o

m

b

o

y

s

(

2

)

P

a

r

t

i

a

l

l

y

(

4

)

K

a

t

h

o

e

y

(

4

)

K

a

t

h

o

e

y

i

n

p

u

b

l

i

c

a

n

d

r

e

c

e

p

t

i

v

e

a

n

a

l

s

e

x

(

4

)

R

e

c

e

p

t

i

v

e

a

n

a

l

s

e

x

(

4

)

G

a

y

m

e

n

(

4

)

K

a

t

h

o

e

y

(

4

)

S

a

o

p

r

a

p

h

e

t

s

o

r

n

g

;

o

f

f

e

r

e

d

t

r

a

n

s

s

e

x

u

a

l

s

e

x

(

m

a

y

b

e

t

e

r

m

e

d

k

a

t

h

o

e

y

s

e

x

b

y

m

e

m

b

e

r

s

o

f

t

h

i

s

g

r

o

u

p

)

(

4

)

R

e

c

e

p

t

i

v

e

v

a

g

i

n

a

l

s

e

x

(

3

)

S

t

r

a

i

g

h

t

m

e

n

(

3

)

N

o

n

e

(

4

)

B

o

t

h

r

e

c

e

p

t

i

v

e

v

a

g

i

n

a

l

a

n

d

r

e

c

e

p

-

t

i

v

e

a

n

a

l

s

e

x

(

1

)

P

a

r

t

n

e

r

s

b

o

t

h

s

t

r

a

i

g

h

t

m

e

n

a

n

d

g

a

y

m

e

n

(

1

)

N

o

t

e

:

L

e

s

b

i

a

n

s

e

x

h

e

r

e

r

e

f

e

r

s

t

o

a

n

y

k

i

n

d

o

f

w

o

m

a

n

t

o

w

o

m

a

n

s

e

x

u

a

l

a

c

t

i

v

i

t

y

(

c

u

n

n

i

l

i

n

g

u

s

,

t

r

i

b

a

d

i

s

m

,

u

s

i

n

g

s

e

x

t

o

y

s

,

r

u

b

b

i

n

g

w

i

t

h

n

g

e

r

s

e

t

c

.

T

o

m

b

o

y

i

s

t

h

e

T

h

a

i

t

e

r

m

f

o

r

a

b

u

t

c

h

l

e

s

b

i

a

n

w

o

m

a

n

.

T

r

a

n

s

s

e

x

u

a

l

s

e

x

i

s

a

t

e

r

m

t

h

a

t

t

h

e

a

u

t

h

o

r

u

s

e

t

o

i

n

d

i

c

a

t

e

s

e

r

v

i

c

e

s

p

r

o

v

i

d

e

d

b

y

s

a

o

p

r

a

p

h

e

t

s

o

r

n

g

.

B

e

c

a

u

s

e

t

h

e

y

h

a

d

m

a

l

e

b

o

d

i

e

s

b

e

f

o

r

e

a

n

d

h

a

v

e

p

r

o

v

i

d

e

d

s

e

x

u

a

l

s

e

r

v

i

c

e

s

i

n

v

a

r

i

o

u

s

e

m

b

o

d

i

m

e

n

t

s

,

t

h

e

y

h

a

v

e

e

x

p

e

r

t

k

n

o

w

l

e

d

g

e

a

n

d

N

e

v

e

r

s

a

y

n

o

t

o

a

n

y

t

o

u

r

i

s

t

r

e

q

u

e

s

t

s

.

T

h

e

y

s

t

r

i

v

e

t

o

b

e

b

e

t

t

e

r

t

h

a

n

n

a

t

u

r

a

l

w

o

m

e

n

i

n

b

e

d

.

T

h

e

y

u

s

e

d

t

e

r

m

s

l

i

k

e

b

e

t

t

e

r

s

e

x

g

r

e

a

t

s

e

x

a

n

d

e

x

t

r

a

s

e

x

t

o

d

e

s

c

r

i

b

e

t

h

e

i

r

s

e

r

v

i

c

e

s

.

568 W. Ocha

objectionable) reveal something about individuals inner subjectivities. Preferred

practices/partners differentiated the informants from one another according to their own

identity labels. Thus identity, embodiment and sexuality are interlinked aspects of the self

that co-varied among these informants.

Changed nexus of identity following surgery

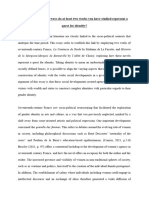

Table 1 shows that the range of gender identities and preferred sexual activities/partners

changed following surgery. Noteworthy is how alterations to the bodies led to

corresponding changes in identity and sexuality, sometimes both, for all of the informants.

Following surgery, the 13 phu-ying split into two identity groups: 7 remained phu-ying

while 6 came to understand themselves to be sao praphet sorng (second kind of woman:

transsexual). All continued in their preference for straight men but, with new bodies,

shifted their preference from receptive anal sex to receptive vaginal sex. Having strong

dislikes in sexual practices/partners seemed more characteristic of phu-ying than of the

other transsexual identities because phu-ying identify themselves as strictly heterosexual:

I think I am a woman so I have to like men, right? (Nicky, 25 years old, Phu-ying sex worker

in a Host Bar, Patpong)

Thais tend to believe that sexuality is either hetero-or homosexual (the author has not

been able to avoid using these terms even though they are inadequate for three-gender

societies), with no other possibilities. The relationship between a straight man and a

kathoey is therefore interpreted as heterosexual (Brummelhuis 1999; van Esterik 2000).

In Thai understandings of sexuality, being receptive makes one a woman. After surgery, of

the seven phu-chai in transition, four became sao praphet sorng, one was kathoey and two

could not explain their identities. The four sao praphet sorng strictly preferred receptive

vaginal sex with straight men, while the kathoey liked both receptive vaginal sex with

straight men and receptive anal sex with gay men. The two who could not explain their

identities preferred receptive vaginal intercourse with straight men and receptive lesbian

sex with tomboys (masculine lesbian women). This ambiguity with respect to partner

preference likely was difcult for these two because the Thai gender system does not take

complex or ambiguous congurations into account.

The four who were kathoey before the surgery remained kathoey, but three shifted their

preference from receptive anal sex with gay men to receptive vaginal sex with straight

men. One of the three liked both.

Some qualities remain stable in the before and after identities in Table 1. The surgery,

however, resulted in new body-identity-sexuality alignments. Surgery made some sexual

activities possible and foreclosed others, such as the presence of a neo-vagina, which

shifted the focus of receptive sexual activity. Another explanation for the new body-

identity-sexuality alignments is the powerful inuence exerted by the surrounding

transsexual culture of which they became a part.

Identity and sub-cultural context

A sector of the sex industry absorbs transsexual women as natural women. These phu-ying

understand themselves in binary terms and express feelings of liberation through the sex

change operations. Six of the seven reported being satised with the transformation, a

greater satisfaction rate than in the other sub-groups (Table 1). After surgery, they gained

fuller acceptance as women by family, friends and partners. Four of them were so

convincing as natural women that it was difcult for tourists or customers to notice their

Culture, Health & Sexuality 569

transsexuality, even after sexual services were performed. These four worked in host bars,

in which they talked with the customers and often went out with them to perform sexual

services. The majority of the workers in these bars were born women and these phu-ying

gave tourists the impression that they were as female as their colleagues. In this

environment, they modeled themselves after the natural women in learning English, how

to please customers and how to behave. They took on a womans aura. They visited

womens organisations, such as the Empower Foundation,

5

for help and felt more

comfortable in those places than in transgender organisations. These four had to practice

and learn to embody womanhood in the same way that Schrock et al.s (2005) transsexuals

did, by reconditioning their movements and voices to match their gender identities.

Though they always appeared as women in the bars, they could offer either phu-ying or

transsexual sex to clients, thus they were able to have either woman or transsexual

identities as the context required.

The remaining 20 transsexual sex workers, the majority of the group, were employed

in cabaret theatres or go-go bars that cultivated a particular third-gender identity and sao

praphet sorng, in order to attract tourists. Sao praphet sorng is the mainstream translation

for MTF transsexuals and is the dominant transsexual identity. Sex reassignment has

modernised kathoey. Sao praphet sorng, because of their new anatomy and sexuality,

represent a gender diversication that is historically new. Table 1 shows the dominance of

the sao praphet sorng identity. Even the 14 who do not identify themselves as sao praphet

sorng adopted the outer appearance and behaviours associated with that identity.

This identity requires the adoption of certain characteristics. Sao praphet sorng are like

natural women, only more so. They cultivate an exaggerated femininity in dress (more

makeup, sexier clothes), speak their own slang, which is well known in the subculture,

and behave in ways that distinguish them from natural women through movement, posture,

body language and eye contact. They exhibit more physical contact and more aggressive

manners in approaching potential clients. The subtle differences between natural women

and sao praphet sorng are easily recognisable to Thai people but are sometimes missed by

tourists.

The sao praphet sorng identity is learned in formal and informal ways. The cabaret

theatres construct the ideal sao praphet sorng, which is subsequently reinforced in various

ways. The six informants who worked in go-go bars had to pass job interviews, health

checks and orientation training before serving tourists. Cabaret theatres have professional

production teams, costume designers, stage conductors, sound engineers, make up artists

and others who as a team reproduce the sao praphet sorng ideal. These 14 artistes

underwent special training (from senior artistes) in manners, dancing, acting, English,

comportment and customer entertainment. They became professionals. Often living as

well as training together, transsexuals develop a strong sense of community. As described

by Tina:

. . . there are lots of people [here] who are more than my colleagues; they are friends and

relatives at the same time. We live together . . . we knowevery matter . . . I learned a lot about

transsexual aura from this workplace. I learned how to make up and make myself look great

in feminine costumes. Now, Im old enough to advise young kathoeys how to behave . . .

(Tina, 32 years old, sao praphet sorng artiste, Alcarzar Theatre)

This group accepted that the transformation of their anatomy could not make them

natural women because they were missing the aura that is instilled in natural women

from birth, moreover, they lacked the reproductive power and experience of natural

women. They tended to perceive natural women as a threat because they can never really

570 W. Ocha

compare with them. Thus, they increased their skills in pleasing men to compensate for not

being natural women.

Besides re-shaping and re-training the outer appearance, transsexuals must receive

instruction on how to use their new genitals. Often they must learn how to fake a womans

orgasm so as to please their customers. They believe that an ability to control the pelvic

muscles increases customers sexual pleasure and learn to do this through informal

training from colleagues. In live shows in go-go bars, the more-talented sex workers hold,

eject or blow objects (ping pong balls, eggs, candles, strings, lit cigarettes, darts,

chopsticks, etc.) with their neo-vaginas. These performances strengthen and control the

pelvic muscles.

Whereas this group could offer themselves sexually as phu-ying before the surgery,

transsexual sex after the surgery encompassed all the forms of sexual activity in which

natural women engage, plus more. Since they had male bodies previously, they claim that

they know exactly what men want. Further, due to their experience in the sex industry and

having had different bodies over the period of their transformation, sao praphet sorng have

had a variety of sexual experiences with different types of tourists from all over the world.

They have a large repertoire of sexual services and a high tolerance for performing acts

they may not prefer. Unlike natural women, sex workers who are encouraged to just say

no if they are made uncomfortable by clients requests, sao praphet sorng sex workers

almost never say no.

Just like Schrock et al.s (2005) sample, the personas of sao prophet sorng must be

practiced and perfected over time but unlike that sample, my informants did not learn to

be women they learned to be a second kind of woman. Their hegemonic model is

embedded in their own sub-culture, not the mainstream culture. By becoming sao praphet

sorng, they were liberated from being phu-ying. They are proud of their identities because

of the fame and money they earn and because they have found a home in the sex tourism

industry.

Sao prophet sorng benet the entertainment/sex industry. As such, their identity is the

repeated inculcation of a norm (Butler 1993, 7). From the eldwork, it seems that

transsexuals are forced into conventional categories of sex/gender and that sao praphet

sorng is a gender categorisation that these transsexuals embrace. However, this category

does not match the core selves of all sex workers. Some transsexuals still have difculty

tting into existing cultural categories, such as sao praphet sorng, kathoey or woman. The

result corresponds with Butlers notion (1990) that there is no gender identity behind the

expressions of gender; identity is performatively constituted by the very expressions that

are said to be its results (25).

In this study, 5 of my 24 respondents resisted the sao praphet sorng label and retained

the traditional kathoey to identity themselves, 4 of whom had felt that they were kathoey

before the surgery as well. This group appears as sao praphet sorng but has a different

sexuality: they are exible in their preferred sexual partners (both straight men and gay

men) while phu-ying and sao praphet sorng unambiguously prefer straight men. Though

all the informants share a standardised embodiment, adherence to a kathoey identity for

some suggests signicant diversity within the transsexual sample. The sao praphet sorng

identity did not include the two informants who could not explain their identities after

surgery.

These ndings show that a dominant identity does not t all. Instead, transsexual sex

workers dene themselves in terms that incorporate (1) their internal core feelings, (2) their

state of embodiment and (3) their sexual preferences.

Culture, Health & Sexuality 571

Residual problems after surgery

There is, however, growing resistance to the sao praphet sorng ideal. The term human

monster (a-manut) is the name given to the negative self-image of transsexuals who are not

happy with their surgical alterations. A total of 11 transsexual informants cited not being

able to reach orgasm, 11 cited the burden of care and expense associated with keeping up

their new bodies, 3 said that the appearance of their faces and bodies was not that of natural

women. Overall, 7 were satised with the transformation, 14 were partially satised and 4

were not satised (Table 1). Ten transsexuals regretted having had vaginoplasty.

Many have begun to question the necessity of full transformation. Is full sex

reassignment worth the risks? Is it the only way to be themselves? These are current topics of

discussion in the subculture. Many transsexuals talk to aspiring transsexuals so that critical

awareness is raised. Bomb, a 21-year-old sao praphet sorng sex worker in Pattaya, stated:

I tell my transgender friends who plan to undergo a vaginoplasty that nobody can guarantee

that it will be 100% functional. Because of this kind of critique, some third genders have

decided to remain in semi-reassigned states. They can do so because their sexual services

supply the demand of a segment of sex tourists who desire unique experiences.

Conclusion

In contemporary Thailand, the third gender has diversied into many distinct identities,

which the global sex trade has helped to shape. Historically, the kathoey image has been a

commonly recognised Thai third gender. The sao praphet sorng (women of a second kind)

identity, however, presents an alternative sense of being.

The sex sector media and their signicant nancial power, play an important roles in

promoting existing and constructing new gender/sexual identities. The capitalisation of the

sex industry is creating new possibilities for the development of gender/sexual identities,

which are inuenced by the modernisation of sex work. Sao praphet sorng cultivate an

exaggerated femininity. They augment their feminine qualities by increasing their skills

in pleasing men to compensate for not being natural women. They feel proud of their

identities because of the fame and money they earn though participation in Thailands sex

tourism in the twenty-rst century. The industry creates a home for sao praphet sorng,

where they can feel and be perceived as more sexually appealing than natural women.

Sex reassignment surgery, which became popular in the twentieth century, modernised

the kathoey identity and has been an important factor in making the concept of gender

more complex. Kathoey deploy medical and particular knowledge in strategic ways to

support the construction of their desired corporeal styles and identities in terms of being

like women which does not necessarily mean to become women in the ways of real

women (Sukontapatipark 2005, ii).

The sao praphet sorng identity does not always harmonise with the individual

characteristics of sex workers they often continue to have diverse sexualities and sexual

preferences. Evidence from this eldwork suggests that bodily surfaces are

transformable, temporary and aesthetically pleasing, while the self remains hidden and

ultimately unknowable. The categories and labels of sex roles and sex acts suggest that a

wide range of gender identities and sexual practices are recognised and tolerated, many of

which cannot be placed into specic gender categories (van Esterik 2000).

This paper shows that the coming together of cultures in Thailands sex tourism

industry, coupled with the advancement of medical technology, is resulting in the

emergence of new concepts of gender. Thus, gender categorisation is best theorised as a

context-sensitive process constructed through interaction with others (Butler 1993).

572 W. Ocha

Gender is a different sort of identity in which identity is repetitively constituted, and its

relation to body reference is complex (Butler 1990, 63). Gendered surfaces are carefully

and aesthetically presented in public to communicate how one expects to be regarded

(van Esterik 2000, 2023).

Notes

1. Queer includes many diverse and marginal sexualities, inter-sex people; human beings whose

biological sex cannot be classied as clearly male or female (Dreger 2001; Money and Ehrhardt

1972) and transgenders. The convergence of feminism and the gay liberation movement,

essentially through the emergence of third wave feminism recognising marginal sexualities, has

resulted in the emergence of queer as an inclusive category (Jagose 1996).

2. Interviews were conducted with a total of 25 full transsexuals; however, one transsexual was

excluded from analysis because, by his own account, he was a gender normative man undergoing

sex reassignment surgery solely for nancial reasons.

3. The author is a cisgender woman, a term that indicates that ones gender identity is congruent

with ones birth sex (Bender-Baird 2008).

4. At the time of the study, the exchange rate was approximately 50 baht to 1GBP.

5. Empower Foundation is a group formed by female sex workers to protect the rights of female

sex workers in terms of violations from clients and bar owners and includes the provision of basic

healthcare knowledge for safe sex and skills training for other employment.

References

Aizura, Aren, Z. 2011. The romance of the amazing scalpel: Race, labour and affect in Thai gender

reassignment clinics. In Queer Bangkok: Twenty-rst century markets, media and rights, ed.

P. Jackson, 14383. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Bender-Baird, Kyla. 2008. Examining cisgender privilege while conducting transgender research.,

Paper presented at the National Womens Studies Association Conference, June 1922, in

Cincinnati, OH.

Brummelhuis, Han ten. 1999. Transformations of transgender: The case of the Thai Kathoey. In Lady

boys, tom boys, rent boys: Male and female homosexualities in contemporary Thailand, ed.

P. Jackson and G. Sullivan, 11736. Haworth, UK: Haworth Press and Chiang Mai, Thailand:

Silkworm Books.

Bunyanathee, Wuthichai, and Manee Piyyopornpanit. 1999. The dynamic of sex tourism: The case of

Southeast Asia. In S. Rungetrakul, Tumra Jitawetchasart [Abnormal psychology]. Bangkok:

Ruen Kaw Publisher.

Butler, Judith. 1990. Gender trouble, feminism and the subversion of identity. New York: Routledge.

Butler, Judith. 1993. Bodies that matter: On the discursive limits of sex. New York: Routledge.

Dreger, Alice, Domurat. 2001. Hermaphrodites and the medical invention of sex. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Gahan, Luke, Benjamin. 2012. Queer spiritual spaces: Sexuality and sacred places (book review).

Culture, Health & Sexuality 14, no. 2: 2379.

Gallagher, Rory. 2005. Shifting market, shifting risks: male and transgender tourist-oriented sex

work in South-East Asia. Paper presented at Sexualities, Genders and Rights in Asia: The rst

International Conference of Queer Studies, July 79, in Bangkok.

Grzelinska, Jo. 2012. Queer methods and methodologies: Intersecting queer theories and social

science research (book review). Culture, Health & Sexuality 14, no. 1: 1135.

Jackson, Peter. 2011. Queer Bangkok: Twenty-rst century, media and rights. Hong Kong:

Hong Kong University Press.

Jackson, Peter, and Gerard Sullivan. 2000. Lady boys, tom boys, rent boys: Male and female

homosexualities in contemporary Thailand. Chiang Mai, Thailand: Silkworm Books.

Jagose, Annamarie. 1996. Queer theory: An introduction. New York: New York University Press.

Kuo, Michello. 2000. Asias dirty secret. Harvard International Review 22, no. 2: 425.

Lorber, Judith. 1996. Beyond the binaries: Depolarizing the categories of sex, sexuality and gender.

Sociological Inquiry 66, no. 2: 14359.

Culture, Health & Sexuality 573

Money, John, and A. Ehrhardt. 1972. Man and woman boy and girl: Differentiation and dimorphism

of gender identity from conception to maturity. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Namaste, Viviane, K. 2000. Invisible lives: The erasure of transsexual and transgendered people.

Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

Ocha, Witchayanee. 2008. Expounding gender: Male and transgender (male-to-female) sex worker

identities in the global-Thai sex sector, PhD Thesis of Gender and Development Studies

Program, Asian Institute of Technology, Pathumthani, Thailand.

Parker, Richard. 2009. Sexuality, culture and society: Shifting paradigms in sexuality research.

Special Issue: Contested Innocence-Sexual Agency in Public and Private Space, Hanoi. Culture,

Health & Sexuality 11, no. 3: 25166.

Roen, Katrina. 2006. Transgender theory and embodiment: The risk of racial marginalization. In The

transgender studies reader, ed. S. Stryker and S. Whittle, 65666. New York: Routledge.

Rubin, Henry. 2003. Self-made men: identity and embodiment among transsexual men. Nashville,

TN: Vanderbilt University Press.

Shrock, Douglas, Lori Reid, and Emily Boyd. 2005. Transsexuals embodiment of womanhood.

Gender & Society 19, no. 3: 31735.

Sinnott, Megan. 2000. The semiotics of transgendered sexual identity in the Thai print media:

Imagery and discourse of the sexual other. Culture, Health & Sexuality 2, no. 4: 42540.

Stryker, Susan. 1994. My words to Victor Frankenstein above the village of Chamounix: Performing

transgender rage. GLQ: A Journal of Gay and Lesbian Studies 1: 23754.

Sukontapatipark, Nantiya. 2005. Relationship between modern medical technology and gender

identity in Thailand: Passing from male bodies to female bodies., Masters Thesis, Mahidol

University.

Tiewtranon, Preecha, and Prayuth Chokrungvaranont. 2004. Sex reassignment surgery in Thailand.

Journal of Thai Medicine 8, no. 11: 14045.

Towle, Evan. B., and Lynn Morgan. 2006. Romancing the transgender native: Rethinking the use of

the third gender concept. In The transgender studies reader, ed. S. Stryker and S. Whittle,

66684. New York: Routledge.

Totman, Richard. 2003. The third sex: Kathoey Thailands ladyboys. London: Souvenir Press.

Valocchi, Steven. 2005. Not yet queer enough: The lessons of queer theory for the sociology of

gender and sexuality. Gender & Society 19, no. 6: 75070.

Van Esterik, Penny. 2000. Materializing Thailand. Oxford: Berg.

Winter, Sam. 2002. Counting Kathoey. Web document on Transgender ASIA Research, Education

and Support Centre. TransgenderASIA website. http://web.hku.hk/,sjwinter/TransgenderASIA

Winter, Sam. 2004. Gender identity formation thermodynamics. International Journal for Gender

Identity Disorder Research 2, no. 1: 713.

Winter, Sam. 2005. Of transgender and sin in Asia. Paper presented at Sexualities, Genders and

Rights in Asia. The First International Conference of Queer Studies, July 79, in Bangkok,

Thailand. Research School of Pacic & Asian Studies, at The Australian National University.

http://bangkok2005.anu.edu.au/papers/Winter.pdf

Winter, Sam. 2011. Transpeople (Khon kham-pket) in Thailand: Transprejudice, exclusion, and the

presumption of mental illness. In Queer Bangkok: Twenty-rst century markets, media and

rights, ed. P. Jackson, 25167. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Resume

Cet article vise a` apporter sa contribution a` la comprehension des identites de genre/sexuelles

emergentes en Tha lande. Ce pays est devenu une destination prisee pour la chirurgie de

transformation sexuelle en fournissant la technologie medicale qui permet la transformation

comple`te, sans trop de procedures operatoires et avec des resultats satisfaisants a` des prix

raisonnables. Les donnees ont ete collectees a` partir dentretiens avec 24 transgenres mtf (hommes

vers femmes) exercant le commerce du sexe a` Pattaya et a` Patpong, des lieux tre`s connus pour le

tourisme sexuel en Tha lande. Les resultats sugge`rent lemergence de nouvelles comprehensions de

lidentite de genre/sexuelle. Le tourisme sexuel et le commerce du sexe apportent un eclairage

important sur le processus a` travers lequel le genre est conteste et repense. La rencontre des cultures

dans lindustrie du sexe en Tha lande, associee aux progre`s de la technologie medicale, a pour

resultat lemergence de nouvelles conceptions du genre.

574 W. Ocha

Resumen

El objetivo de este art culo es ayudar a entender las nuevas identidades sexuales/de genero en

Tailandia. Tailandia se ha convertido en un destino popular para las operaciones de cambio de sexo

porque dispone de la tecnolog a medica para una completa transformacion, con relativamente pocos

procedimientos y resultados satisfactorios a un precio razonable. Para este estudio, se recogieron los

datos de 24 transexuales de hombre a mujer que trabajan en la industria sexual de Pattaya y Patpong,

centros activos bien conocidos del turismo sexual en Tailandia. Los resultados indican la aparicion

de nuevos conceptos de la identidad sexual/de genero. El turismo y el trabajo sexual destacan en gran

medida el proceso por el que se cuestiona y reimagina cada sexo. El encuentro de las culturas en la

industria sexual de Tailandia, unido a los avances de tecnolog a medica, ha dado lugar a la aparicion

de nuevos conceptos del sexo.

Culture, Health & Sexuality 575

Copyright of Culture, Health & Sexuality is the property of Routledge and its content may not be copied or

emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission.

However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- +2017 Auditory Verbal Hallucinations and The Differential Diagnosis of Schizophrenia and Dissociative DisordersDocumento10 pagine+2017 Auditory Verbal Hallucinations and The Differential Diagnosis of Schizophrenia and Dissociative DisordersjuaromerNessuna valutazione finora

- ++L. Mark S. Micale, Paul Lerner-Traumatic Pasts - History, Psychiatry, and Trauma in The Modern Age, 1870-1930-Cambridge University Press (2001)Documento333 pagine++L. Mark S. Micale, Paul Lerner-Traumatic Pasts - History, Psychiatry, and Trauma in The Modern Age, 1870-1930-Cambridge University Press (2001)juaromer50% (2)

- 2017 - Behavioral AddictionsDocumento6 pagine2017 - Behavioral AddictionsjuaromerNessuna valutazione finora

- Conklin Malone Fowler 2012 Mentalization and The RorschachDocumento26 pagineConklin Malone Fowler 2012 Mentalization and The RorschachjuaromerNessuna valutazione finora

- 2015, Standards, Accuracy, and Questions of Bias in Rorschach Meta-AnalysesDocumento11 pagine2015, Standards, Accuracy, and Questions of Bias in Rorschach Meta-AnalysesjuaromerNessuna valutazione finora

- 1992, Meloy, Revisiting The Rorschach of Sirhan SirhanDocumento23 pagine1992, Meloy, Revisiting The Rorschach of Sirhan SirhanjuaromerNessuna valutazione finora

- 2015, Standards, Accuracy, and Questions of Bias in Rorschach Meta-AnalysesDocumento11 pagine2015, Standards, Accuracy, and Questions of Bias in Rorschach Meta-AnalysesjuaromerNessuna valutazione finora

- Watkins 2012 The Competent Psychoanalytic SupervisorDocumento10 pagineWatkins 2012 The Competent Psychoanalytic SupervisorjuaromerNessuna valutazione finora

- Sarnat 2011, Supervising Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, Present KnowledgeDocumento10 pagineSarnat 2011, Supervising Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, Present KnowledgejuaromerNessuna valutazione finora

- Gronnerod - Rorschach Assessment of Changes After PsychotherDocumento21 pagineGronnerod - Rorschach Assessment of Changes After PsychotherjuaromerNessuna valutazione finora

- Limitations To The Capacity To Love, KernbergDocumento16 pagineLimitations To The Capacity To Love, KernbergjuaromerNessuna valutazione finora

- 2016, Di Nuovo Validity Indices of The Rorschach Test and PersonalityDocumento20 pagine2016, Di Nuovo Validity Indices of The Rorschach Test and PersonalityjuaromerNessuna valutazione finora

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Singh, Hays, Watson Strength in The Face of Adversit, Resilience Strategies of Transgender Individuals, +Documento9 pagineSingh, Hays, Watson Strength in The Face of Adversit, Resilience Strategies of Transgender Individuals, +juaromerNessuna valutazione finora

- An Interpretative PhenomenologDocumento335 pagineAn Interpretative PhenomenologGhost hackerNessuna valutazione finora

- GE ELECT Gender and Society-Module 1Documento20 pagineGE ELECT Gender and Society-Module 1Jean Rema GonjoranNessuna valutazione finora

- Gender Identity and Socialization ProcessDocumento20 pagineGender Identity and Socialization ProcessPragyan Paramita MishraNessuna valutazione finora

- Ethics and Rights in Counselling - LGBTQ+Documento10 pagineEthics and Rights in Counselling - LGBTQ+ManaliNessuna valutazione finora

- A Content Analysis of Gender-Fair Language in The English Modules of The Department of EducationDocumento102 pagineA Content Analysis of Gender-Fair Language in The English Modules of The Department of EducationClaudine BaluyotNessuna valutazione finora

- Gender and Sexual Diversities BriefingDocumento11 pagineGender and Sexual Diversities Briefingmohamedemam95Nessuna valutazione finora

- Video SocioDocumento2 pagineVideo Socioanida nabilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Gender Identity DevelopmentDocumento3 pagineGender Identity DevelopmentLucía LópezNessuna valutazione finora

- Inclusive Language Guide: Diversity and Inclusion Directorate, Ministry of DefenceDocumento30 pagineInclusive Language Guide: Diversity and Inclusion Directorate, Ministry of DefenceGuido FawkesNessuna valutazione finora

- Soft Skills NotesDocumento122 pagineSoft Skills NotesThiba SathivelNessuna valutazione finora

- 2023.05.25 TN Zinner ComplaintDocumento35 pagine2023.05.25 TN Zinner ComplaintNews Channel 9Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Queer and Transgender Resilience Workbook 1Documento226 pagineThe Queer and Transgender Resilience Workbook 1nikola 89100% (1)

- Gender DysphoriaDocumento4 pagineGender Dysphoriavaibhavi BarkaNessuna valutazione finora

- Test Bank For Gender Ideas Interactions Institutions 2nd by WadeDocumento8 pagineTest Bank For Gender Ideas Interactions Institutions 2nd by WadeAshley Piper100% (24)

- Simon LeVay - The Sexual BrainDocumento156 pagineSimon LeVay - The Sexual BrainAdriana MendozaNessuna valutazione finora

- Gender Identity Development Among Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Emerging Adults An Intersectional ApproachDocumento21 pagineGender Identity Development Among Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Emerging Adults An Intersectional ApproachMarta Cañero PérezNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Construction of Gender PDFDocumento23 pagineSocial Construction of Gender PDFApu100% (4)

- Gender SocializationDocumento14 pagineGender SocializationKainat JameelNessuna valutazione finora

- 26 Supremo Amicus 378Documento7 pagine26 Supremo Amicus 378smera singhNessuna valutazione finora

- A. Complete Blood Count (CBC)Documento6 pagineA. Complete Blood Count (CBC)raul nino MoranNessuna valutazione finora

- Gender and EducationDocumento6 pagineGender and EducationCrimson BirdNessuna valutazione finora

- Theo.2 Chapter 6Documento13 pagineTheo.2 Chapter 6Baozi dumpsNessuna valutazione finora

- Sexual Politics SummativeDocumento11 pagineSexual Politics Summativejames.frainNessuna valutazione finora

- Geder Studies Past PPR SolvedDocumento24 pagineGeder Studies Past PPR Solvedosmosis.2896Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Expression: "Toni Gee"Documento21 pagineSexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Expression: "Toni Gee"Lapuyan Rural Health UnitNessuna valutazione finora

- Multicultural PD FinalDocumento46 pagineMulticultural PD Finalapi-452946482Nessuna valutazione finora

- Why Does Gender Matter Counteracting Stereotypes With Young Children Olaiya E Aina and Petronella A CameronDocumento10 pagineWhy Does Gender Matter Counteracting Stereotypes With Young Children Olaiya E Aina and Petronella A CameronAnnie NNessuna valutazione finora

- Class Action Trans Women ComplaintDocumento25 pagineClass Action Trans Women ComplaintNews TeamNessuna valutazione finora

- 2011-Transgender and Gender Variant Populations With Mental Illness, Implication For Clinical PracticeDocumento6 pagine2011-Transgender and Gender Variant Populations With Mental Illness, Implication For Clinical PracticejuaromerNessuna valutazione finora