Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Historical Notes On The Tinwhistle

Caricato da

too_many_liesDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Historical Notes On The Tinwhistle

Caricato da

too_many_liesCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Historical Notes on the Tinwhistle

By L.E. McCullough.

From

The Complete Irish Tinwhistle Tutor.

I like this little academic introduction to the tinwhistle, which appears in L.E

. McCullough's excellent tutor. Thanks to our friend L.E. for permission to repr

oduce it on Chiff & Fipple. Call 1-800-431-7187 to get a copy. A CD is now inclu

ded! Dr. McCullough's website is http://feadaniste.tripod.com/

"Sweet as pipe-music was the melodius sound of the maiden's voice and her Gaelic

" -Accalam na Senorach (The Colloquy of the Ancient Men), 12th century.

"Pipes, fiddles, men of no valour, bone-players and pipe-players; a crowd hideou

s, noisy, profane, shriekers and shouters"-"The Fair of Carman" in The Book of L

einster, c. 1160 A.D.

The instrument now known among Irish musicians as the tinwhistle, penny-whistle,

or tinflute, has a lengthy pedigree in the historical annals of Irish music. Wh

ile the oldest surviving specimens are the 12th-century bone whistles recently u

nearthed at the High Street excavations in the old Norman quarter of Dublin, var

ious types of whistle flutes that were the progenitors of the modern tinwhistle

are frequently mentioned in the ancient tales and in the laws governing ancient

Irish society. There is the tale in which Ailen, a chief of the fairy tribe Tuat

ha de Danann, uses the feadan to cast a spell of sleep over the inhabitants of t

he High King's palace at Tara, so that he can carry out his annual November Eve

vengeance. Players of the feadan are also mentioned in the description of the Ki

ng of Ireland's court found in the Brehon Laws dating from the 3rd century A.D.

The 12th-century reference in the poem about the pre-Here's L.E. McCullough. Sto

ne sober. Christian Fair of Carman includes cuisleannach (players of the cuisle,

or pipe) among the entertainers, despite an obvious aesthetic disapproval on th

e poet's part. A more complimentary view of the cuisle is expressed by the 12th-

century compiler of the Acallam na Senorach in the comparison of its timbre and

the sound of a maiden's speech. One of the most interesting references occurs in

an ancient poem found in the Teach Miodhchuarta where the seating plan of the r

oyal feasts at Tara is given; cuisleannach are placed in the same division as sm

iths, shield-makers, jugglers, trumpeters, shoemakers, and fishermen, to name a

few of their social compatriots. It might be of some interest to note that the c

uisleannach received the pig's thigh as their allotted portion.

Through the efforts of 19th-century specialists in ancient Irish society, it has

been possible to obtain some insight into the nature of the various "musical pi

pes" that flourished during this time. Both the feadan (also called feadog) and

cuisle (also called cuiseach) refer to a "pipe, tube,artery,vein" and were made

by hollowing out the stalks of plants such as elder, cane, and other wild grasse

s and reeds (an additional meaning of feadan is "a hollowed stick"). Uileann pip

emaker Patrick Hennelly of Chicago recalled that as a young lad in Mayo, he ofte

n made musical instruments from ripe oat straws simply by pushing out the pith a

nd then fashioning the lip and fingerholes with a penknife, and, indeed, the bas

ic structural principles of such instruments must have been discovered fairly ea

rly and by many people. Later, as the technology advanced, more permanent materi

als such as wood and bone came into use, and various fipples, tongues, and reeds

were devised for sounding the instruments.

Stone high-crosses of the 9th, lOth, and 11th centuries reveal these pipes to ha

ve been straight or sometimes slightly curved up at the bottom. They possessed n

arrow conical bores that widened toward the bottom and are estimated to have bee

n between 14 and 24 inches long. Currently-manufactured tinwhistles in the key o

f Bb (actually pitched two whole tones below concert pitch) measure 14 3/4 inche

s in length, but there is little reliable information about the scales or pitch

resources of the feadan or cuisle. Possibly, harmonics or over-blown notes may h

ave been used, as is the case with similar types of simple flutes throughout the

world. End-blown pipes representative of the general type found in medieval Bri

tain and Ireland were discovered in Somerset and Monmouthshire, England. Made of

deer bone, they each had five front fingerholes; one had two rear thumbholes, w

hile the other pipe had one. One pipe had a range of 11/2 octaves, the other 21/

2. These pipes were restored to playable condition, and it was found that each c

ould give diatonic scales (as can the modern tinwhistle) It is not unlikely that

a relatively sophisticated music was played on ancient bone pipes of this kind.

Occasionally, these pipes were depicted as being played in twos and threes by th

e same player; this might have been achieved by holding two or three different p

ipes in the hands, similar to the ancient Greek aulos and Roman tibia. In ancien

t times double reeds made of cane were used to sound the pipes. It is possible t

hat the tubes were bound together like the parallel double and triple pipes stil

l found in Eastern and Southern Europe and North Africa. In any case, the possib

ility exists that harmonies and countermelodies may have been practiced by playe

rs of the feadan and cuisle.

There is some difference of opinion concerning the instrument known as the buinn

e (or bunne). Some scholars believe it was a horn or trumpet used for military a

nd hunting purposes rather than general musical entertainment, while others thin

k it was similar to the feadan and cuisle and was equipped with a single reed in

the mouthpiece. What might clinch the argument is that the buinnire were seated

at the King's feasts at Tara alongside the players of the corn (trumpet).

The modern tinwhistle belongs to the species of musical instruments called flage

olets, of which the recorder is a familiar example. The terms "whistle flutes" o

r "fipple flutes" are also used to designate flageolets and refer to the method

of sound production. The fipple is an apparatus formed by a small plug or block,

usually of wood, set into the mouthpiece, or, in some cases, is part of the mou

thpiece itself. The fipples in the bone flutes from the Middle Ages were made of

clay. A small space or duct is created between the edge of the fipple and the i

nside wall of the instrument; the player's airstream is directed by this fipple/

duct system against a sharp edge or lip that is cut into the tube below the fipp

le, thereby producing sound. This type of vertically-blown flute became known to

Europe around the 11th century, according to musicologiSts, and exists today in

various forms throughout the world.

Copyright 1976 by Silver Spear Publications, 1987 by Oak Publications. Used by p

ermission.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Legendary hunters: The whaling indians: West Coast legends and stories — Part 9 of the Sapir-Thomas Nootka textsDa EverandLegendary hunters: The whaling indians: West Coast legends and stories — Part 9 of the Sapir-Thomas Nootka textsNessuna valutazione finora

- Experimentation and Interpretation: the Use of Experimental Archaeology in the Study of the PastDa EverandExperimentation and Interpretation: the Use of Experimental Archaeology in the Study of the PastNessuna valutazione finora

- Archaeology of MusicDocumento84 pagineArchaeology of Musicapi-320216112Nessuna valutazione finora

- Balfour Henry The Old British Pibcorn or HornDocumento16 pagineBalfour Henry The Old British Pibcorn or HornИгнаций ЛойолаNessuna valutazione finora

- Early Music 2008 Chadwick 521 32Documento12 pagineEarly Music 2008 Chadwick 521 32Alex Kylikov100% (1)

- EG Chapter 1 Excerpt 2 PDFDocumento6 pagineEG Chapter 1 Excerpt 2 PDFjuanNessuna valutazione finora

- Bandamanna Saga. Ed. Hallvard MagerøyDocumento166 pagineBandamanna Saga. Ed. Hallvard MagerøyMihai SarbuNessuna valutazione finora

- Faithful Harpers and Phantom PipersDocumento7 pagineFaithful Harpers and Phantom PipersSeán Donnelly100% (4)

- Mangrini, Manhood and Music in W. CreteDocumento32 pagineMangrini, Manhood and Music in W. CreteYiannis Alygizakis100% (1)

- Mesk The Traditional Teaching System of PDFDocumento6 pagineMesk The Traditional Teaching System of PDFVictor Navarro GarciaNessuna valutazione finora

- Armed For Eternity Notes On Knightly SwordsDocumento4 pagineArmed For Eternity Notes On Knightly SwordsRamiro GuerreroNessuna valutazione finora

- Cold Steel, Weak Flesh Mechanism, Masculinity and The Anxieties of Late Victorian EmpireDocumento27 pagineCold Steel, Weak Flesh Mechanism, Masculinity and The Anxieties of Late Victorian Empirelobosolitariobe278Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Brief History of The QuarterstaffDocumento8 pagineA Brief History of The QuarterstaffTony TollidayNessuna valutazione finora

- Medieval Whales and WhalingDocumento6 pagineMedieval Whales and WhalingThames Discovery ProgrammeNessuna valutazione finora

- Celtic Provenance in Traditional HerbalDocumento19 pagineCeltic Provenance in Traditional HerbalFabio C. NunesNessuna valutazione finora

- A Helmet in The Church of St. Mary Bury PDFDocumento14 pagineA Helmet in The Church of St. Mary Bury PDFRoque BastosNessuna valutazione finora

- Northumbrian Minstrelsey 1808Documento116 pagineNorthumbrian Minstrelsey 1808MichaelPearceNessuna valutazione finora

- Proiect Engleza Irish FoodDocumento4 pagineProiect Engleza Irish FoodAdrianNessuna valutazione finora

- Ireland's Four Cycles of Myth and Legend: TH THDocumento3 pagineIreland's Four Cycles of Myth and Legend: TH THAnonymous OuZdlENessuna valutazione finora

- The Ocarina - A Tutorial 1Documento58 pagineThe Ocarina - A Tutorial 1inanimatecontentNessuna valutazione finora

- Stanley B Green Field - A Readable Beowulf - The Old English Epic Newly Translated PDFDocumento172 pagineStanley B Green Field - A Readable Beowulf - The Old English Epic Newly Translated PDFddrocks302Nessuna valutazione finora

- Van Dijk-Bull-Lyres 2013 PDFDocumento18 pagineVan Dijk-Bull-Lyres 2013 PDFaminNessuna valutazione finora

- Tree TIpsDocumento4 pagineTree TIpsKirk RodriguezNessuna valutazione finora

- New Old Azeri Musical Intervals-1 PDFDocumento8 pagineNew Old Azeri Musical Intervals-1 PDFRyan O'CoffeyNessuna valutazione finora

- SSD Article One For Korea1Documento5 pagineSSD Article One For Korea1api-278193099Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Malham Pipe A Reassessment of Its Context Dating and SignificanceDocumento40 pagineThe Malham Pipe A Reassessment of Its Context Dating and SignificanceCorwen BrochNessuna valutazione finora

- Beowulf and ArchaeologyDocumento21 pagineBeowulf and ArchaeologyHarry RoseNessuna valutazione finora

- Documenting Nepalese Musical TraditionsDocumento7 pagineDocumenting Nepalese Musical TraditionspremgurungNessuna valutazione finora

- How Musical Was The Sung Office Some ObsDocumento12 pagineHow Musical Was The Sung Office Some ObsDan DumitricaNessuna valutazione finora

- Playing by The Rules: Swords and Swordfighters in The Mycenaean Society, Alexandra TarleaDocumento26 paginePlaying by The Rules: Swords and Swordfighters in The Mycenaean Society, Alexandra TarleaFlorea Mihai StefanNessuna valutazione finora

- Burials Upper Mantaro Norconck & OwenDocumento37 pagineBurials Upper Mantaro Norconck & OwenManuel Fernando Perales MunguíaNessuna valutazione finora

- Thomas Morley, A Plaine Thomas MorleyDocumento7 pagineThomas Morley, A Plaine Thomas Morleypetrushka1234Nessuna valutazione finora

- 5 Yeroulanou P Rev-Opt-SecDocumento10 pagine5 Yeroulanou P Rev-Opt-SeccoolerthanhumphreyNessuna valutazione finora

- Finlay (Ed.) - Essays On FornaldarsogurDocumento147 pagineFinlay (Ed.) - Essays On FornaldarsogurMihai Sarbu100% (1)

- The MabinongionDocumento95 pagineThe MabinongionmmoudNessuna valutazione finora

- The Theme of Wine-Drinking and The Concept of The Beloved in Early Persian PoetryDocumento12 pagineThe Theme of Wine-Drinking and The Concept of The Beloved in Early Persian Poetryo2156158100% (2)

- The Galpin Society Journal Volume 35 Issue 1982 (Doi 10.2307 - 841247) Review by - Bo Lawergren - The British Museum Yearbook 4 - Music and Civilisationby T. C. MitchellDocumento7 pagineThe Galpin Society Journal Volume 35 Issue 1982 (Doi 10.2307 - 841247) Review by - Bo Lawergren - The British Museum Yearbook 4 - Music and Civilisationby T. C. MitchellAri MVPDLNessuna valutazione finora

- Arabic & Persian Archive TonkDocumento15 pagineArabic & Persian Archive TonkNajaf HaiderNessuna valutazione finora

- The Wooden Finds From Perry OaksDocumento15 pagineThe Wooden Finds From Perry OaksFramework ArchaeologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Horn AntennasDocumento29 pagineHorn AntennasAbderrahmane BadisNessuna valutazione finora

- The Influence of Byzantine Music On The PDFDocumento14 pagineThe Influence of Byzantine Music On The PDFErdinç Yalınkılıç100% (1)

- Modern Scottish Minstrel 3Documento332 pagineModern Scottish Minstrel 3Fe0% (1)

- Saga Book XXXDGDGDGDGDDocumento152 pagineSaga Book XXXDGDGDGDGDSal Ie Em100% (1)

- Old Celtic Lenguages - Celtic in Northern Italy PDFDocumento14 pagineOld Celtic Lenguages - Celtic in Northern Italy PDFTaurīni100% (2)

- Arnold, ''Local Festivals at Delos''Documento8 pagineArnold, ''Local Festivals at Delos''Claudio CastellettiNessuna valutazione finora

- BagpipeDocumento1 paginaBagpipeAmanda Dwisstya UtamiNessuna valutazione finora

- CentralasianMusic GlossaryDocumento8 pagineCentralasianMusic GlossarywyldoneNessuna valutazione finora

- Oakeshott, E. (1974) - "The Sword The Serpent of Blood" en Dark Age Warrior. Londres, Lutterworth Press.Documento20 pagineOakeshott, E. (1974) - "The Sword The Serpent of Blood" en Dark Age Warrior. Londres, Lutterworth Press.Daniel Grisales BetancurNessuna valutazione finora

- (ARCHAEOLOGY) (MEDIEVAL) Bequest - Catalogue of The Finger Ring or Early Christian, Byzantine, Teutonic, Mediaeval and Later... 1912 PDFDocumento500 pagine(ARCHAEOLOGY) (MEDIEVAL) Bequest - Catalogue of The Finger Ring or Early Christian, Byzantine, Teutonic, Mediaeval and Later... 1912 PDFAsafteiRoxanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Druce - Animals in English Wood CarvingsDocumento28 pagineDruce - Animals in English Wood Carvingsmdreadinc2Nessuna valutazione finora

- When The Celtic Tiger Roared: Ireland's Golden Age For ArchaeologyDocumento8 pagineWhen The Celtic Tiger Roared: Ireland's Golden Age For ArchaeologyBrendon WilkinsNessuna valutazione finora

- Southeast Asian Music Q1Documento164 pagineSoutheast Asian Music Q1Sepida MolzNessuna valutazione finora

- Early Lyres in Context JHillberg-3Documento61 pagineEarly Lyres in Context JHillberg-3Maurizio DemichelisNessuna valutazione finora

- Beowulf MS (Zupitza 1882)Documento302 pagineBeowulf MS (Zupitza 1882)thefallenghost6108Nessuna valutazione finora

- Bagpipe in ItalyDocumento8 pagineBagpipe in ItalyAntonio BaianoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Celtic Sword (Pleiner 1993)Documento245 pagineThe Celtic Sword (Pleiner 1993)Pertinax1983Nessuna valutazione finora

- Janissary Music: Çeri: New Troop' Ger. Janitscharen Musik, Türkische MusikDocumento4 pagineJanissary Music: Çeri: New Troop' Ger. Janitscharen Musik, Türkische Musikscrire100% (1)

- FLP10078 Norway FiddleDocumento9 pagineFLP10078 Norway FiddletazzorroNessuna valutazione finora

- The noble Polish Lada family. Die adlige polnische Familie Lada.Da EverandThe noble Polish Lada family. Die adlige polnische Familie Lada.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Folk Music of IrelandDocumento17 pagineFolk Music of Irelandtoo_many_liesNessuna valutazione finora

- US Coast Guard - Boat Crew Seamanship ManualDocumento1.242 pagineUS Coast Guard - Boat Crew Seamanship ManualJared A. Lang100% (7)

- Higher Algebra - Hall & KnightDocumento593 pagineHigher Algebra - Hall & KnightRam Gollamudi100% (2)

- Understanding Shielded CableDocumento5 pagineUnderstanding Shielded Cablewasim_scribedNessuna valutazione finora

- Queer Theory Analysis in Chapter 1 of Jeffrey Eugenides's "Middlesex"Documento5 pagineQueer Theory Analysis in Chapter 1 of Jeffrey Eugenides's "Middlesex"Fitrie GoesmayantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Genre and Institututions Rothery e Stenglin (1997)Documento38 pagineGenre and Institututions Rothery e Stenglin (1997)Gabriel LimaNessuna valutazione finora

- Formwork 11Documento77 pagineFormwork 11Anish OhriNessuna valutazione finora

- Kishore Kumar-Rona Nahi Rona (Kasam Se)Documento2 pagineKishore Kumar-Rona Nahi Rona (Kasam Se)Azam-Savaşçı Anderson MohammadNessuna valutazione finora

- Sunset BoulevardDocumento2 pagineSunset BoulevardLeonardo Ciscomani GurrolaNessuna valutazione finora

- 1000 Books To ReadDocumento76 pagine1000 Books To Readdarkdarkhbk100% (1)

- NudeRevolutionary Calendar 2012-13Documento16 pagineNudeRevolutionary Calendar 2012-13orangesanguine57% (7)

- Department of Physics Bs Physics 4Th (A) : INSTRUCTORDocumento2 pagineDepartment of Physics Bs Physics 4Th (A) : INSTRUCTORAdeel RashidNessuna valutazione finora

- Menu PDFDocumento12 pagineMenu PDFSeyed IbrahimNessuna valutazione finora

- Types of Housing: Cottage KotrqyDocumento7 pagineTypes of Housing: Cottage KotrqyОлінька СтецюкNessuna valutazione finora

- Dante Illustrations and Notes 1890Documento192 pagineDante Illustrations and Notes 1890dubiluj100% (3)

- Lens AberrationDocumento2 pagineLens AberrationJann ClaudeNessuna valutazione finora

- Employment Relations Excred 1Documento3 pagineEmployment Relations Excred 1api-547578648Nessuna valutazione finora

- Spataro, M. Et Al. Non-Destructive Examination Porcelain. 2009Documento11 pagineSpataro, M. Et Al. Non-Destructive Examination Porcelain. 2009Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Puerto Plata Dominican Republic Has It AllDocumento4 paginePuerto Plata Dominican Republic Has It AllDoñe PerezNessuna valutazione finora

- Catch Basin Detail: Property LineDocumento1 paginaCatch Basin Detail: Property LineB R PAUL FORTINNessuna valutazione finora

- Soul Making, Appropriation and Improvisation: Learning Outcomes by The End of This Lesson, You Should Be Able ToDocumento4 pagineSoul Making, Appropriation and Improvisation: Learning Outcomes by The End of This Lesson, You Should Be Able ToApril CaringalNessuna valutazione finora

- Effects of Emotional Appeal Used in Tele PDFDocumento3 pagineEffects of Emotional Appeal Used in Tele PDFNova Mae FrancasNessuna valutazione finora

- Blu-Ray DiscDocumento12 pagineBlu-Ray DiscVenkata RamanaNessuna valutazione finora

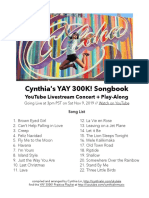

- Cynthia's YAY 300K SongbookDocumento26 pagineCynthia's YAY 300K Songbookdan100% (2)

- The Heritage Monuments of Kashmir: A Study of Some Existing and Ruined Structures of Later Medieval PeriodDocumento4 pagineThe Heritage Monuments of Kashmir: A Study of Some Existing and Ruined Structures of Later Medieval PerioddeepakNessuna valutazione finora

- Husserl Historicism 1Documento2 pagineHusserl Historicism 1gustavoalbertomaseraNessuna valutazione finora

- Howard ShanetDocumento25 pagineHoward ShanetDimitris ChrisanthakopoulosNessuna valutazione finora

- Cancionero 3ºDocumento17 pagineCancionero 3ºAnonymous 3HnQzg1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Adobe Lightroom Keyboard Shortcuts - Windows Version 1Documento4 pagineAdobe Lightroom Keyboard Shortcuts - Windows Version 1ron2008Nessuna valutazione finora

- Assignment in ITCDocumento6 pagineAssignment in ITCWilliam L. Apuli IINessuna valutazione finora

- My Dear FriendsDocumento5 pagineMy Dear FriendsНастя Семенчук100% (1)

- On The Blue Comet Discussion GuideDocumento2 pagineOn The Blue Comet Discussion GuideCandlewick PressNessuna valutazione finora

- Advent & ChristmasDocumento41 pagineAdvent & ChristmasSirRafKinGLNessuna valutazione finora

- Upper Intermediate Quick Check Test 1A: GrammarDocumento2 pagineUpper Intermediate Quick Check Test 1A: GrammarCavad İbrahimliNessuna valutazione finora