Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Chavez - Sandiganbayan

Caricato da

Stephanie Thomas0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

29 visualizzazioni14 pagineCase digests

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

DOCX, PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCase digests

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato DOCX, PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

29 visualizzazioni14 pagineChavez - Sandiganbayan

Caricato da

Stephanie ThomasCase digests

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato DOCX, PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 14

Chavez vs. Judicial and Bar Council, G.R. No.

202242, July 17, 2012

Facts: In 1994, instead of having only seven members, an eighth member was added to the JBC

as two representatives from Congress began sitting in the JBC one from the House of

Representatives and one from the Senate, with each having one-half (1/2) of a vote. Then, the

JBC En Banc, in separate meetings held in 2000 and 2001, decided to allow the representatives

from the Senate and the House of Representatives one full vote each. At present, Senator Francis

Joseph G. Escudero and Congressman Niel C. Tupas, Jr. (respondents) simultaneously sit in the

JBC as representatives of the legislature. It is this practice that petitioner has questioned in this

petition. Respondents argued that the crux of the controversy is the phrase a representative of

Congress. It is their theory that the two houses, the Senate and the House of Representatives,

are permanent and mandatory components of Congress, such that the absence of either divests

the term of its substantive meaning as expressed under the Constitution. Bicameralism, as the

system of choice by the Framers, requires that both houses exercise their respective powers in the

performance of its mandated duty which is to legislate. Thus, when Section 8(1), Article VIII of

the Constitution speaks of a representative from Congress, it should mean one representative

each from both Houses which comprise the entire Congress. Respondents further argue that

petitioner has no real interest in questioning the constitutionality of the JBCs current

composition. The respondents also question petitioners belated filing of the petition.

Issues:

(1) Whether or not the conditions sine qua non for the exercise of the power of judicial review

have been met in this case; and

(2) Whether or not the current practice of the JBC to perform its functions with eight (8)

members, two (2) of whom are members of Congress, runs counter to the letter and spirit of the

1987 Constitution.

Held:

(1) Yes. The Courts power of judicial review is subject to several limitations, namely: (a) there

must be an actual case or controversy calling for the exercise of judicial power; (b) the person

challenging the act must have standing to challenge; he must have a personal and substantial

interest in the case, such that he has sustained or will sustain, direct injury as a result of its

enforcement; (c) the question of constitutionality must be raised at the earliest possible

opportunity; and (d) the issue of constitutionality must be the very lis mota of the case.

Generally, a party will be allowed to litigate only when these conditions sine qua non are present,

especially when the constitutionality of an act by a co-equal branch of government is put in

issue.

The Court disagrees with the respondents contention that petitioner lost his standing to sue

because he is not an official nominee for the post of Chief Justice. While it is true that a

personal stake on the case is imperative to have locus standi, this is not to say that only official

nominees for the post of Chief Justice can come to the Court and question the JBC composition

for being unconstitutional. The JBC likewise screens and nominates other members of the

Judiciary. Albeit heavily publicized in this regard, the JBCs duty is not at all limited to the

nominations for the highest magistrate in the land. A vast number of aspirants to judicial posts all

over the country may be affected by the Courts ruling. More importantly, the legality of the very

process of nominations to the positions in the Judiciary is the nucleus of the controversy. The

claim that the composition of the JBC is illegal and unconstitutional is an object of concern, not

just for a nominee to a judicial post, but for all citizens who have the right to seek judicial

intervention for rectification of legal blunders.

(2) Yes. The word Congress used in Article VIII, Section 8(1) of the Constitution is used in its

generic sense. No particular allusion whatsoever is made on whether the Senate or the House of

Representatives is being referred to, but that, in either case, only a singular representative may be

allowed to sit in the JBC. The seven-member composition of the JBC serves a practical purpose,

that is, to provide a solution should there be a stalemate in voting.

It is evident that the definition of Congress as a bicameral body refers to its primary function

in government to legislate. In the passage of laws, the Constitution is explicit in the distinction

of the role of each house in the process. The same holds true in Congress non-legislative

powers. An inter-play between the two houses is necessary in the realization of these powers

causing a vivid dichotomy that the Court cannot simply discount. This, however, cannot be said

in the case of JBC representation because no liaison between the two houses exists in the

workings of the JBC. Hence, the term Congress must be taken to mean the entire legislative

department. The Constitution mandates that the JBC be composed of seven (7) members only.

Notwithstanding its finding of unconstitutionality in the current composition of the JBC, all its

prior official actions are nonetheless valid. Under the doctrine of operative facts, actions

previous to the declaration of unconstitutionality are legally recognized. They are not nullified.

Manila Prince Hotel v. Government Service Insurance System

G.R. No. 122156, February 3, 1997, 267 SCRA 408

FACTS: The Government Service Insurance System (GSIS), pursuant to the privatization

program of the government, decided to sell through public bidding 30% to 51 % of the issued

and outstanding shares of respondent Manila Hotel (MHC). In a close bidding, only two bidders

participated. Petitioner Manila Prince, a Filipino Corporation, which offered to buy 51% of the

MHC at P41.58 per share and Renong Berhad, a Malaysian Firm, which bid for the same number

of shares at P44.00 per share. Pending the declaration of Renong Berhad as the winning bidder,

petitioner matches the bid price of P44.00 per share by Renong Berhad. Subsequently, petitioner

sent a manager's check as bid security to match the bid of Renong Berhad which respondent

GSIS refuse to accept. Apprehensive that GSIS has disregarded the tender of the matching bid

and that the sale may be consummated which Renong Berhad, petitioner filed a petition before

the Supreme Court.

ISSUE: Whether or not petitioner should be preferred after it has match the bid offered of

Malaysian firm under Section 10, second paragraph of Article 12 of the 1987 Constitution.

RULING: A constitution is a system of fundamental laws for the governance and administration

of a nation. It is supreme, imperious, absolute and unalterable except by the authority from which

it emanates. Since the constitution is the fundamental, paramount and supreme law of the nation,

it is deemed written in every statute and contract. Article 12, Section 10, paragraph 2 of the 1987

Constitution provides that "in the grant of rights, privileges, and concessions covering the

national economy and patrimony, the State shall give preference to qualified Filipinos." It means

just that qualified Filipinos shall be preferred. When the Constitution speaks of "national

patrimony", it refers not only to the natural resources of the Philippines but also to the cultural

heritage of the Filipinos. Manila Hotel has become a landmark- a living testimonial of Philippine

Heritage. While it was restrictively an American Hotel when it first opened, it immediately

evolved to be truly Filipino. Verily, Manila Hotel has become part of our national economy and

patrimony. Respondents further argue that the Constitutional provision is addressed to the State,

not to GSIS which by itself possesses a separate and distinct personality. In constitutional

jurisprudence, the acts of a person distinct from the government are considered "state action"

covered by the Constitution (1) when the activity it engages is a public function; (2) when the

government is so significantly involved with the private actor as to make the government

responsible for his action; and (3) when the government has approved or authorized the action.

Without doubt, the transaction entered into by the GSIS is in fact a transaction of the State and

therefore subject to the constitutional command. Therefore, the GSIS is directed to accept the

matching bid of petitioner Manila Prince Hotel.

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES v. SANDIGANBAYAN, MAJOR

GENERAL

JOSEPHUS Q. RAMAS AND ELIZABETH DIMAANO

The resulting government [from the EDSA Revolution] was a

revolutionary government bound by no constitution or legal limitations excep

t treaty obligations that the revolutionary government, as the de jure government in the

Philippines, assumed under international law. The Bill of Rights under the 1973 Constitution was

not operative during the interregnum. Nevertheless, even during the interregnum the Filipi

no people continued to enjoy, under the Covenant and the Declaration, almost the same rights

found in the Bill of Rights of the 1973 Constitution. The revolutionary government did not r

epudiate the Covenant or the Declaration during the interregnum.

The Presidential Commission on Good Government (the PCGG), through the AFP Anti-

Graft Board (the Board), investigated reports of unexplained wealth involving Major General

Josephus Ramas (Ramas), the Commanding General of the Philippine Army during the time of

former President Ferdinand Marcos. Pursuant to said investigation, the Constabulary r

aiding team served a search and seizure warrant on the premises of Ramas alleged mistress

Elizabeth Dimaano. Aside from the military equipment stated in the warrant, items not included

in the warrant, particularly, communications equipment, land titles, jewelry, and several

thousands of cash in pesos and US dollars, were also seized.

In its Resolution, the AFP Board reported that (1) Dimaano could not have used the said

equipment without Ramas consent; and (2) Dimaano could not be the owner of the money

because she has no visible source of income. The Board then concluded with a recommendation

that Ramas be prosecuted for violation of R.A. 3019, otherwise known as the Anti-Graft and

Corrupt Practices Act and R.A. 1379, otherwise known as the Act for the Forfeiture of

Unlawfully Acquired Property. Accordingly, Solicitor General Francisco I. Chavez, in behalf of

the Republic of the Philippines (the Republic or Petitioner) filed a Complaint again

st Ramas and Dimaano. On 18 November 1991, the Sandiganbayan dismissed the complaint on

the grounds that (1) the PCGG has no jurisdiction to investigate the private respondents and (2)

the search and seizure conducted was illegal.

ISSUES: Whether or not the properties confiscated in Dimaanos house were illegally seized and

therefore inadmissible in evidence.

HELD: Thus, during the interregnum when no constitution or Bill of Rights existed, directives

and orders issued by government officers were valid so long as these officers did not exceed the

authority granted them by the revolutionary government. The directives and orders should not

have also violated the Covenant or the Declaration. In this case, the revolutionary government

presumptively sanctioned the warrant since the revolutionary government did not repudiate it.

The warrant, issued by a judge upon proper application, specified the items to be searched and

seized. The warrant is thus valid with respect to the items specifically described in the warrant.

However, the Constabulary raiding team seized items not included in the warrant the monies,

communications equipment, jewelry and land titles confiscated. The raiding team had no legal

basis to seize these items without showing that these items could be the subject of warrantless

search and seizure. Clearly, the raiding team exceeded its authority when it seized these items.

The seizure of these items was therefore void, and unless these items are contraband per se, and

they are not, they must be returned to the person from whom the raiding seized them. However,

we do not declare that such person is the lawful owner of these items, merely that the search and

seizure warrant could not be used as basis to seize and withhold these items from the possessor.

We thus hold that these items should be returned immediately to Dimaano.

Javellana vs. Executive Secretary

Facts:

The Plebiscite Case

On March 16, 1967, Congress of the Philippines passed Resolution No. 2, as amended

byResolution No. 4, calling for a Constitutional Convention to propose amendments to thePhilippine

Constitution. Said Resolution was implemented by Republic Act No. 6132, for theelection of

delegates of the said Convention. Hence, the 1971 Constitutional Convention beganto perform its

functions on June 1, 1971. While the Convention was in session on September 21, 1972, the

President issued Proclamation No. 1081 placing the entire Philippines under Martial Law.On

November 29, 1972, the Convention approved its Proposed Constitution of the Republic of the

Philippines. The next day, November 30, 1972, the President of the Philippines

issuedPresidential Decree No. 73, which is an order for setting and appropriating of funds for

aplebiscite for the ratification or rejection of the proposed Constitution as drafted by the

1971Constitutional Convention.On December 7, 1972, Charito Planas filed a case against the Commission on

Elections, theTreasurer of the Philippines and the Auditor General, to enjoin said respondents or

their agentsfrom implementing Presidential Decree No. 73, on the grounds that the President

does not havethe legislative authority to call a plebiscite and the appropriation of public funds for

the purposeare lodged exclusively by the Constitution in Congress and there is no proper

submission to thepeople of said Proposed Constitution set for January 15, 1973, there being no

freedom of speech, press and assembly, and there being no sufficient time to inform the people

of thecontents thereof.On December 23, 1972, the President announced the postponement of the

plebiscite for theratification or rejection of the Proposed Constitution. The Court deemed it fit to

refrain, for thetime being, from deciding the aforementioned case.In the afternoon of January 12, 1973,

the petitioners in Case G.R. No. L-35948 filed an "urgentmotion," praying that said case be decided "as

soon as possible, preferably not later thanJanuary 15, 1973." The next day, January 13, 1973, the Court

issued a resolution requiring therespondents to comment and file an answer to the said "urgent motion" not

later than Tuesday

noon, January 16, 1973." When the case was being heard, the Secretary of Justice called onand

said that, upon instructions of the President, he is delivering a copy of Proclamation No.1102,

which had just been signed by the President earlier that morning.Proclamation No. 1102,

declares that Citizen Assemblies referendum was conducted, and thatthe result shows that more

than 95% of the members of the Citizens Assemblies are in favor of the new Constitution and

majority also answered that there was no need for a plebiscite andthat the vote of the Citizens

Assemblies should be considered as a vote in a plebiscite. The thenPresident of the Philippines,

Marcos, hereby certify and proclaim that the Constitution proposedby the 1971 Constitutional

Convention has been ratified by an overwhelming majority of all of the votes cast by the members of the

Citizens Assemblies throughout the Philippines, and hasthereby come into effect.

The Ratification Case

On January 20, 1973, Josue Javellana filed case against the Executive Secretary and

theSecretaries of National Defense, Justice and Finance, to restrain said respondents "and

their subordinates or agents from implementing any of the provisions of the propose Constitution

notfound in the present Constitution" referring to that of 1935.Javellana alleged that the

President had announced "the immediate implementation of the NewConstitution, thru his

Cabinet, respondents including," and that the latter "are acting without, or in excess of

jurisdiction in implementing the said proposed Constitution" upon the ground: "thatthe President,

as Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of the Philippines, is withoutauthority to create the

Citizens Assemblies"; that the same "are without power to approve theproposed Constitution ...";

"that the President is without power to proclaim the ratification by theFilipino people of the

proposed Constitution"; and "that the election held to ratify the proposedConstitution was not a

free election, hence null and void."

Issue:

1. Whether or not the issue of the validity of Proclamation No. 1102 involves a justiciable

or political question.

2. Whether or not the proposed new or revised Constitution been ratified to said Art. XV of

the1935 Constitution.

3. Whether or not the proposed Constitution aforementioned been approved by a majority of

thepeople in Citizens' Assemblies allegedly held throughout the Philippines.

4. Whether or not the people acquiesced in the proposed Constitution.

5. Whether or not the parties are entitled to any relief.

Ruling:

The court was severely divided on the following issues raised in the petition: but when thecrucial

question of whether the petitioners are entitled to relief, six members of the court(Justices

Makalintal, Castro, Barredo, Makasiar, Antonio and Esguerra) voted to dismiss thepetition.

Concepcion, together Justices Zaldivar, Fernando and Teehankee, voted to grant therelief being

sought, thus upholding the 1973 Constitution.

First Issue

On the first issue involving the political-question doctrine Justices Makalintal, Zaldivar,

Castro,Fernando, Teehankee and myself, or six (6) members of the Court, hold that the issue of

thevalidity of Proclamation No. 1102 presents a justiciable and non-political question.

JusticesMakalintal and Castro did not vote squarely on this question, but, only inferentially, in

their discussion of the second question. Justice Barredo qualified his vote, stating that "inasmuch asit is claimed

there has been approval by the people, the Court may inquire into the question of whether or not

there has actually been such an approval, and, in the affirmative, the Courtshould keep hands-off

out of respect to the people's will, but, in negative, the Court maydetermine from both factual

and legal angles whether or not Article XV of the 1935 Constitutionbeen complied with."

Justices Makasiar, Antonio, Esguerra, or three (3) members of the Courthold that the issue is

political and "beyond the ambit of judicial inquiry."

Second Issue

On the second question of validity of the ratification, Justices Makalintal, Zaldivar, Castro,Fernando,

Teehankee and myself, or six (6) members of the Court also hold that theConstitution proposed

by the 1971 Constitutional Convention was not validly ratified inaccordance with Article XV,

section 1 of the 1935 Constitution, which provides only one way for ratification, i.e., "in an

election or plebiscite held in accordance with law and participated in onlyby qualified and duly

registered voters.

Philippine Bar Association vs. COMELEC

140 SCRA 455

January 7, 1986

FACTS:

11 petitions were filed for prohibition against the enforcement of BP 883 which calls for special

national elections on February 7, 1986 (Snap elections) for the offices of President and Vice

President of the Philippines. BP 883 in conflict with the constitution in that it allows the

President to continue holding office after the calling of the special election.

Senator Pelaez submits that President Marcos letter of conditional resignation did not create

the actual vacancy required in Section 9, Article 7 of the Constitution which could be the basis of

the holding of a special election for President and Vice President earlier than the regular

elections for such positions in 1987. The letter states that the President is: irrevocably vacat(ing)

the position of President effective only when the election is held and after the winner is

proclaimed and qualified as President by taking his oath office ten (10) days after his

proclamation.

The unified opposition, rather than insist on strict compliance with the cited constitutional

provision that the incumbent President actually resign, vacate his office and turn it over to the

Speaker of the Batasang Pambansa as acting President, their standard bearers have not filed any

suit or petition in intervention for the purpose nor repudiated the scheduled election. They have

not insisted that President Marcos vacate his office, so long as the election is clean, fair and

honest.

ISSUE:

Is BP 883 unconstitutional, and should the Supreme Court therefore stop and prohibit the holding

of the elections

HELD:

The petitions in these cases are dismissed and the prayer for the issuance of an injunction

restraining respondents from holding the election on February 7, 1986, in as much as there are

less than the required 10 votes to declare BP 883 unconstitutional.

The events that have transpired since December 3,as the Court did not issue any restraining

order, have turned the issue into a political question (from the purely justiciable issue of the

questioned constitutionality of the act due to the lack of the actual vacancy of the Presidents

office) which can be truly decided only by the people in their sovereign capacity at the scheduled

election, since there is no issue more political than the election. The Court cannot stand in the

way of letting the people decide through their ballot, either to give the incumbent president a

new mandate or to elect a new president.

LAWYERS LEAGUE FOR A BETTER PHILIPPINES vs. AQUINO

(G.R. No. 73748 - May 22, 1986)

FACTS:

On February 25, 1986, President Corazon Aquino issued Proclamation No. 1 announcing that she

and Vice President Laurel were taking power.

On March 25, 1986, proclamation No.3 was issued providing the basis of the Aquino

government assumption of power by stating that the "new government was installed through a

direct exercise of the power of the Filipino people assisted by units of the New Armed Forces of

the Philippines."

ISSUE:

Whether or not the government of Corazon Aquino is legitimate.

HELD:

Yes. The legitimacy of the Aquino government is not a justiciable matter but belongs to the

realm of politics where only the people are the judge.

The Court further held that:

The people have accepted the Aquino government which is in effective control of the entire

country;

It is not merely a de facto government but in fact and law a de jure government; and

The community of nations has recognized the legitimacy of the new government.

In Re: Saturnino Bermudez (G.R. No. 76180 )

I mmunity from Suits

Facts:

This is a petition for declaratory relief filed by the petitioner Bermudez seeking for the

clarification of Sec. 5, Art. 18 of the proposed 1986 Constitution, as quoted:

Sec. 5. The six-year term of the incumbent President and Vice-President elected in the

February 7, 1986 election is, for purposes of synchronization of elections, hereby extended to

noon of June 30, 1992.

The first regular elections for the President and Vice-President under this Constitution shall

be held on the second Monday of May, 1992.

Petitioner sought the aid of the Court to determine as to whom between the incumbent

Pres. Aquino and VP Laurel and elected Pres. Marcos and VP Tolentino the said provision refers

to.

Issue: Whether the Court should entertain the petition for declaratory relief?

Held:

It is elementary that this Court assumes no jurisdiction over petitions for declaratory

relief.(Note: ROC provides that the jurisdiction for petitions for declaratory relief is with the

RTC )

More importantly, the petition amounts in effect to a suit against the incumbent President of

the Republic, President Corazon C. Aquino, and it is equally elementary that incumbent

Presidents are immune from suit or from being brought to court during the period of their

incumbency and tenure.

It being a matter of public record and common public knowledge that the

Constitutional Commission refers therein to incumbent President Corazon C. Aquino and Vice-

President Salvador H. Laurel, and to no other persons, and provides for the extension of their

term to noon of June 30, 1992 for purposes of synchronization of election.

In Re Letter of Associate Justice Reynato Puno

Facts:

Petitioner Assoc. Justice Puno, a member of the Court of Appeals (CA), wrote a letter

dated Nov. 14, 1990 addressed to the Supreme Court about the correction of his seniority ranking

in the CA. It appears from the records that petitioner was first appointed as associate justice of

the CA on June 20, 1980 but took his oath of office on Nov. 29, 1982. The CA was reorganized

and became the Intermediate Appellate Court (IAC) pursuant to Batas Pambansa Blg. 129, "An

Act Reorganizing the Judiciary Appropriating Funds Therefor and For Other Purposes." He was

then appointed as appellate justice and later accepted an appointment to be a deputy minister of

Justice in the Ministry of Justice. In Edsa Revolution in Feb. 1986 brought about reorganization

of the entire government including the judiciary. A Screening Committee was created. When

Pres. Cory Aquino issued Executive Order No. 33, as an exercise of her legislative power, the

Screening Committee assigned the petitioner to rank no. 11 from being the assoc. justice of the

NEW CA. However, the petitioner's ranking changed from no. 11, he now ranked as no. 26. He

alleges that the change in his seniority ranking would be contrary to the provisions of issued

order of Pres. Aquino. The court en banc ranted Justice Puno's request. A motion for

consideration was later filed by Campos and Javelliano who were affected by the change of

ranking. They contend that the petitioner cannot claim such reappointment because the court he

had previously been appointed ceased to exist at the date of his last appointment.

Issue:

Whether the present CA is a new court or merely a continuation of the CA and IAC that

would negate any claim to seniority enjoyed by the petitioner existing prior to said EO No. 33.

Held:

The present CA is a new entity, different and distinct from the CA or the IAC, for it was

created in the wake of the massive reorganization launched by the revolutionary government of

Corazon Aquino in the people power. A revolution has been defined as the complete overthrow

of the established government in any country or state by those who were previously subject to it

as as sudden, radical, and fundamental change in the government or political system, usually

effected with violence. A government as a result of people's revolution is considered de jure if it

is already accepted by the family of nations or countries like the US, Great Britain, Germany,

Japan, and others. In the new government under Pres. Aquino, it was installed through direct

exercise of the Filipino power. Therefore, it is the present CA that would negate the claims of

Justice Puno concerning his seniority ranking.

De Leon vs Esguerra 153 scra 602

Facts:

Alfredo de Leon won as barangay captain and other petitioners won as councilmen of barangay

dolores, taytay, rizal. On february 9, 1987, de leon received memo antedated december 1, 1986

signed by OIC Gov. Benhamin Esguerra, february 8, 1987, designating

Florentino Magno, as new captain by authority of minister of local government and similar

memo signed february 8, 1987, designated new councilmen.

Issue:

Whether or not designation of successors is valid.

Held:

No, memoranda has no legal effect.

1. Effectivity of memoranda should be based on the date when it was signed. So, February 8,

1987 and not December 1, 1986.

2. February 8, 1987, is within the prescribed period. But provisional constitution was no longer

in efffect then because 1987 constitution has been ratified and its transitory provision, Article

XVIII, sec. 27 states that all previous constitution were suspended.

3. Constitution was ratified on February 2, 1987. Thus, it was the constitution in effect.

Petitioners now acquired security of tenure until fixed term of office for barangay officials has

been fixed. Barangay election act is not inconsistent with constitution.

Lambino Vs. Comelec Case Digest

Lambino Vs. Comelec

G.R. No. 174153

Oct. 25 2006

Facts: Petitioners (Lambino group) commenced gathering signatures for an initiative petition to

change the 1987 constitution, they filed a petition with the COMELEC to hold a plebiscite that

will ratify their initiative petition under RA 6735. Lambino group alleged that the petition had

the support of 6M individuals fulfilling what was provided by art 17 of the constitution. Their

petition changes the 1987 constitution by modifying sections 1-7 of Art 6 and sections 1-4 of Art

7 and by adding Art 18. the proposed changes will shift the present bicameral- presidential form

of government to unicameral- parliamentary. COMELEC denied the petition due to lack of

enabling law governing initiative petitions and invoked the Santiago Vs. Comelec ruling that RA

6735 is inadequate to implement the initiative petitions.

Issue:

Whether or Not the Lambino Groups initiative petition complies with Section 2, Article XVII of

the Constitution on amendments to the Constitution through a peoples initiative.

Whether or Not this Court should revisit its ruling in Santiago declaring RA 6735 incomplete,

inadequate or wanting in essential terms and conditions to implement the initiative clause on

proposals to amend the Constitution.

Whether or Not the COMELEC committed grave abuse of discretion in denying due course to

the Lambino Groups petition.

Held: According to the SC the Lambino group failed to comply with the basic requirements for

conducting a peoples initiative. The Court held that the COMELEC did not grave abuse of

discretion on dismissing the Lambino petition.

1. The Initiative Petition Does Not Comply with Section 2, Article XVII of the Constitution on

Direct Proposal by the People

The petitioners failed to show the court that the initiative signer must be informed at the time of

the signing of the nature and effect, failure to do so is deceptive and misleading which renders

the initiative void.

2. The Initiative Violates Section 2, Article XVII of the Constitution Disallowing Revision

through Initiatives

The framers of the constitution intended a clear distinction between amendment and revision,

it is intended that the third mode of stated in sec 2 art 17 of the constitution may propose only

amendments to the constitution. Merging of the legislative and the executive is a radical change,

therefore a constitutes a revision.

3. A Revisit of Santiago v. COMELEC is Not Necessary

Even assuming that RA 6735 is valid, it will not change the result because the present petition

violated Sec 2 Art 17 to be a valid initiative, must first comply with the constitution before

complying with RA 6735

Defensor Santiago vs. Comelec

FACTS:

Private respondent filed with public respondent Commission on Elections (COMELEC) a

Petition to Amend the Constitution, to Lift Term Limits of Elective Officials, by Peoples

Initiative (Delfin Petition) wherein Delfin asked the COMELEC for an order (1) Fixing the time

and dates for signature gathering all over the country; (2) Causing the necessary publications of

said Order and the attached Petition for Initiative on the 1987 Constitution, in newspapers of

general and local circulation; and (3) Instructing Municipal Election Registrars in all Regions of

the Philippines, to assist Petitioners and volunteers, in establishing signing stations at the time

and on the dates designated for the purpose. Delfin asserted that R.A. No. 6735 governs the

conduct of initiative to amend the Constitution and COMELEC Resolution No. 2300 is a valid

exercise of delegated powers. Petitioners contend that R.A. No. 6375 failed to be an enabling law

because of its deficiency and inadequacy, and COMELEC Resolution No. 2300 is void.

ISSUE:

Whether or not (1) the absence of subtitle for such initiative is not fatal, (2) R.A. No. 6735 is

adequate to cover the system of initiative on amendment to the Constitution, and (3) COMELEC

Resolution No. 2300 is valid. .

HELD:

NO. Petition (for prohibition) was granted. The conspicuous silence in subtitles simply means

that the main thrust of the Act is initiative and referendum on national and local laws. R.A. No.

6735 failed to provide sufficient standard for subordinate legislation. Provisions COMELEC

Resolution No. 2300 prescribing rules and regulations on the conduct of initiative or

amendments to the Constitution are declared void.

RATIO:

Subtitles are intrinsic aids for construction and interpretation. R.A. No. 6735 failed to provide

any subtitle on initiative on the Constitution, unlike in the other modes of initiative, which are

specifically provided for in Subtitle II and Subtitle III. This deliberate omission indicates that the

matter of peoples initiative to amend the Constitution was left to some future law.

The COMELEC acquires jurisdiction over a petition for initiative only after its filing. The

petition then is the initiatory pleading. Nothing before its filing is cognizable by the COMELEC,

sitting en banc. The only participation of the COMELEC or its personnel before the filing of

such petition are (1) to prescribe the form of the petition; (2) to issue through its Election

Records and Statistics Office a certificate on the total number of registered voters in each

legislative district; (3) to assist, through its election registrars, in the establishment of signature

stations; and (4) to verify, through its election registrars, the signatures on the basis of the

registry list of voters, voters affidavits, and voters identification cards used in the immediately

preceding election.

Since the Delfin Petition is not the initiatory petition under R.A. No. 6735 and COMELEC

Resolution No. 2300, it cannot be entertained or given cognizance of by the COMELEC. The

respondent Commission must have known that the petition does not fall under any of the actions

or proceedings under the COMELEC Rules of Procedure or under Resolution No. 2300, for

which reason it did not assign to the petition a docket number. Hence, the said petition was

merely entered as UND, meaning, undocketed. That petition was nothing more than a mere scrap

of paper, which should not have been dignified by the Order of 6 December 1996, the hearing on

12 December 1996, and the order directing Delfin and the oppositors to file their memoranda or

oppositions. In so dignifying it, the COMELEC acted without jurisdiction or with grave abuse of

discretion and merely wasted its time, energy, and resources.

Aquino vs. Enrile

FACTS: Enrile (then Minister of National Defense), pursuant to the order of Marcos issued and

ordered the arrest of a number of individuals including Benigno Aquino Jr even without any

charge against them. Hence, Aquino and some others filed for habeas corpus against Juan Ponce

Enrile. Enriles answer contained a common and special affirmative defense that the arrest is

valid pursuant to Marcos declaration of Martial Law.

ISSUE: Whether or not Aquinos detention is legal in accordance to the declaration of Martial

Law.

HELD: The Constitution provides that in case of invasion, insurrection or rebellion, or imminent

danger against the state, when public safety requires it, the President may suspend the privilege

of the writ of habeas corpus or place the Philippines or any part therein under Martial Law. In the

case at bar, the state of rebellion plaguing the country has not yet disappeared, therefore, there is

a clear and imminent danger against the state. The arrest is then a valid exercise pursuant to the

Presidents order.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Electoral Processes ReviewerDocumento172 pagineElectoral Processes ReviewerThea Faith SonNessuna valutazione finora

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- House and Senate GOP Letter To Sal Pace, Brandon Shaffer, John Hickenlooper On Prop 103Documento5 pagineHouse and Senate GOP Letter To Sal Pace, Brandon Shaffer, John Hickenlooper On Prop 103ColoradoPeakPoliticsNessuna valutazione finora

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Annotated BibliographyDocumento4 pagineAnnotated Bibliographyapi-310724932Nessuna valutazione finora

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- N5 Skills Revision Modern StudiesDocumento18 pagineN5 Skills Revision Modern StudiesRaymond MacDougallNessuna valutazione finora

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Recall Petition - Cody Chambers - Second - May 18Documento2 pagineRecall Petition - Cody Chambers - Second - May 18Alissa BohallNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Lambino v. ComelecDocumento1 paginaLambino v. ComelecMirandaKarrivinNessuna valutazione finora

- Rise of Populism in Western EuropeDocumento5 pagineRise of Populism in Western EuropeNoor Ul AinNessuna valutazione finora

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Sanidad vs. COMELECDocumento1 paginaSanidad vs. COMELECDonna de RomaNessuna valutazione finora

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Populist Constitutionalism and Meaningful Popular EngagementDocumento12 paginePopulist Constitutionalism and Meaningful Popular EngagementPaul BlokkerNessuna valutazione finora

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

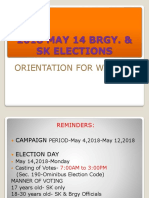

- Orientation For WatchersDocumento44 pagineOrientation For WatchersNewCovenantChurchNessuna valutazione finora

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Guardian 02 December 2021Documento48 pagineThe Guardian 02 December 2021Netko BezimenNessuna valutazione finora

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Voting Problems MemoDocumento2 pagineVoting Problems MemoCeleste KatzNessuna valutazione finora

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Sanidad v. Comelec, 181 Scra 529 (1990)Documento6 pagineSanidad v. Comelec, 181 Scra 529 (1990)ag832bNessuna valutazione finora

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- Election Day 2019Documento2 pagineElection Day 2019Lia Khusnul KhotimahNessuna valutazione finora

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocumento2 pagineCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsNessuna valutazione finora

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Chartist MovementDocumento3 pagineThe Chartist MovementMouaci NwlNessuna valutazione finora

- Stability and Development StrategyDocumento34 pagineStability and Development StrategySudan North-South Border InitiativeNessuna valutazione finora

- Election Law NotesDocumento20 pagineElection Law NotesChristian AbenirNessuna valutazione finora

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Recep Tayyip Erdoğan - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocumento29 pagineRecep Tayyip Erdoğan - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaPaul CokerNessuna valutazione finora

- Alunan III vs. Mirasol, 276 SCRA 501Documento5 pagineAlunan III vs. Mirasol, 276 SCRA 501Inez PadsNessuna valutazione finora

- The First Philippine Legislature Was The First Representative Legislature of The PhilippinesDocumento5 pagineThe First Philippine Legislature Was The First Representative Legislature of The PhilippinesRiciel Marie MarronNessuna valutazione finora

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Tolentino V COMELECDocumento1 paginaTolentino V COMELECKevin DegamoNessuna valutazione finora

- Bylaws of The Ieee Student Branch at Northern India Engineering College, DelhiDocumento7 pagineBylaws of The Ieee Student Branch at Northern India Engineering College, DelhiAyush SagarNessuna valutazione finora

- 167941-2013-Federico v. Commission On ElectionsDocumento14 pagine167941-2013-Federico v. Commission On ElectionsAyra ArcillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Karak: Registered Voters Voters by GenderDocumento4 pagineKarak: Registered Voters Voters by GenderZahid AliNessuna valutazione finora

- Problemset1 PDFDocumento2 pagineProblemset1 PDFqwentionNessuna valutazione finora

- Article V: Suffrage: Prepared by Raizza CorpuzDocumento16 pagineArticle V: Suffrage: Prepared by Raizza CorpuzBeverly A. CannuNessuna valutazione finora

- Strategic PlanDocumento21 pagineStrategic PlanaacdccNessuna valutazione finora

- PCO HandbookDocumento48 paginePCO HandbookemmettoconnellNessuna valutazione finora

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Martial Law and The New SocietyDocumento4 pagineMartial Law and The New Societykenchan smithNessuna valutazione finora

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)