Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Notteboom Et Al

Caricato da

BiYa Khan0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

180 visualizzazioni21 pagineStakeholder Relations Management in ports: dealing with the interplay of forces among stakeholders in a changing competitive environment

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

DOC, PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoStakeholder Relations Management in ports: dealing with the interplay of forces among stakeholders in a changing competitive environment

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato DOC, PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

180 visualizzazioni21 pagineNotteboom Et Al

Caricato da

BiYa KhanStakeholder Relations Management in ports: dealing with the interplay of forces among stakeholders in a changing competitive environment

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato DOC, PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 21

Stakeholder Relations Management in ports:

dealing with the interplay of forces among

stakeholders in a changing competitive

environment

Theo E. Notteboom, Associate Professor, ITMMA University of Antwerp, theo.notteboom@ua.ac.be

i!!y in"e!mans, #ean of ITMMA University of Antwerp an$ %hairman of the &!emish Ports

%ommission, wi!!y.win"e!mans@ua.ac.be

ABSTRACT

A whole series of changes in the field of world economics such as the globalisation of

production and consumption and the structural changes in inter-port relations, port-

hinterland relationships and logistics, have strengthened the role of ports as nodes in

the global transport system. These tendencies and the expansion of the role of the

private sector in port activities have forced ports to become more market-oriented and

to cope with a lot of risks and uncertainties. At the same time, one can observe a

growing awareness for external effects of port activity and the related risks and harms

for community groups. As a result, port authorities have to cope and to interact with a

large number of internal and external groups, each with their own interests and

objectives.

This paper deals with the interplay of forces among different stakeholders directly and

indirectly involved in port activity and port development. The stakeholders approach

is applied to the port sector, in particular to landlord ports. Furthermore, it

demonstrates how different stakeholders are repositioning themselves in the interplay

of forces and how landlord port authorities can cope with the new port environment

using takeholder !elations "anagement #!"$.

Keywords%

port management, stakeholders, port policy

&aper for 'A"( &A)A"A *++* ,"aritime (conomics% setting the foundations for port and shipping

policies-, &anama .ity, &anama, /0-/1 )ovember *++*

/

INTR!"CTIN

The interest in stakeholder approaches to strategic management is growing around the

world #"ills 2 3einstein, *+++$. 4rganisations possess multiple goals and those can

only be achieved by the co-operation of a group of people commonly known as

stakeholders, each with their own specific goals. The stakeholders approach meets the

need for more open communication between employers and employees, between

governmental authorities and public or private companies, between authorities and

civilians or citi5ens, etc. 'n the framework of a global economy such an approach

becomes even more important.

There is no clear definition of ,stakeholders-, so the use of the expression

,stakeholder- is certainly not univocal. The classification of stakeholders depends on

the purpose. This inevitably leads to a wide diversity in interpretations of who can be

classified as a stakeholder #see e.g. 6onaldson 2 &reston, /771$. 'n the broa$ view

stakeholders are described as any individual or group having interest or being affected

by the corporation. The narrow view only recognises stakeholders whose relationship

is primarily of an economic8contractual kind #hankman, /777$.

This paper deals with the interplay of forces among different stakeholders directly and

indirectly involved in port activity and port development. The stakeholders approach

is applied to the port sector. Furthermore, it demonstrates how different stakeholders

are repositioning themselves in the interplay of forces and how landlord port

authorities could cope with the new port environment using takeholder !elations

"anagement #!"$.

This discussion paper does not provide the reader with straight answers to all aspects

of !". "oreover, the paper is focussed on landlord ports and does not touch on the

issue of operating ports. 't should therefore be regarded as a step towards further

research in this field on a case-by-case basis.

T#$ STA%$#&!$RS A''RAC# IN T#$ 'RT S$CTR

&ort managers are increasingly faced with the dilemma of how to reconcile the

competing claims of all kinds of stakeholders, certainly when it comes to port

development and especially to port extension.

A port both technologically and economically is in fact a node for contacts and

contracts, whereby every stakeholder is driven by his own interests and priorities.

&orts are associations where a multitude of individuals and interests #should$

collaborate for the creation and distribution of wealth. 9ence, the value creation

process in ports is dependent upon the support of the different stakeholders groups.

(ach group of stakeholders however merits consideration for its own sake.

'n a port context, one could argue that stakeholders are groups8persons with legitimate

interests in procedural and8or substantive aspects of port activity and port

development. 'n the narrow view the port-s stakeholders include% shareholders,

managers, employees, port users, service providers and other economic players in and

around the port #including port customers, etc..$. 'n the broa$ view on stakeholders

*

also community stakeholders should by included #e.g. community groups and

environmentalists$, because they may experience actual or potential harms or benefits

as a result of port action or inaction. 't is possible that some community stakeholders

may be unaware of their relationship to the port until a specific event - favourable or

unfavourable - draws their attention. triking examples of such third party impacts

exist in relation to large investments in port infrastructure #cf. in terms of

environmental harms and economic benefits that may be experienced by

communities$. The broad view should also include producers and consumers of

products that move through the port, as they are often cited as the political basis for

financial support.

(ig)re *: The port as a node for contacts and contracts +from the perspective

of a ,landlord- port a)thority.

'ource( authors

0

INT$RNA& STA%$#&!$RS

Groups inside port authority organization Managers Employees Board members S#AR$#&!$RS

$/T$RNA& STA%$#&!$RS SEA (IN/OUT) PORT HINTERLAND (OUT/IN)

Groups not part of port authority organization

TRANSPORT OPERATOR GROUPS

(including branch organizaion!)

"arii#$ ran!%or Tran!hi%#$n & !orag$ Rail

Shipping line Stevedoring companies Railway companies

Inland !hi%%ing

'alu$(add$d aci)ii$! Inland barge operators

Logistic service providers Road haulag$

Trucking companies

TRANSPORT ORGANISATION GROUPS

(including branch organizaion!)

Shipping agent Freight orwarder

Logistic service providers !"#L and $#L%

SUPPORTING SER'I*ES Towage companies

(including branch organizaion!) #ilotage services

Ship chandlers

Repair services !c& shiprepair' container repair%

(aste reception acilities

Inspection services

Banks' insurance companies' &&&

Legal irms !lawyers' &&%

INDUSTR+ GROUPS industries in oreland industrial companies in port industries in hinterland

(including branch organizaion!)

(PU,LI*) IN-RASTRU*TURE *OORDINATION. port authorities o other seaports

-A*ILITATION & "ANAGE"ENT GROUPS Inland terminal authorities

Rail inrastructure management companies

)entral' regional and local public authorities !c& roads' !inland% waterways' &&%

Supranational public organisations !c& E*' (orld Bank%

LEGISLATION & PU,LI* POLI*+ GROUPS central and regional governments !including port commissions%

European *nion

Trade negotiations groups !c& (T+%

*O""UNIT+ GROUPS Local inhabitants groups

)onsumers, ta- payers

Environmentalist groups o a local' regional or global scale

The press

. the /port/ or /port community/ as perceived by many e-ternal entities

Figure / depicts a port as a coalition of interest groups based on the broader view on

stakeholders. The perspective is that of a landlord port authority. The functional

relationships among the different stakeholders groups are not indicated. A graphical

representation of all contractual and non-contractual relationships among the

individual groups is hardly possible as there are so many of them.

Internal stakeholders

The internal stakeholders are part of the comprehensive port authority organi5ation.

Apart from the aim to realise port authority objectives the top management of a port

authority might also envisage more personal goals such as salary, prestige and power.

The employees are interested in their wages, working conditions and personal

development. A good human resources management #9!"$ with an eye for

motivation and reward is indispensable.

The public, semi-public or private shareholders pursue goals such as return on

investment, shareholder8stakeholder value and8or welfare creation. The identification

of the true shareholders of a port authority is not always an easy task. A large number

of landlord port authorities are of the #semi-$public kind with strong links to a

municipality, a city, a region or province. The true shareholders of a public port

authority de facto are the taxpayers on the relevant geographical level. As such, the

general public has a univocal role to play% in many cases the #local$ public is at the

same time external stakeholder and indirect shareholder. The same kind of reasoning

is valid in case of public investments in port infrastructure by local, regional, national

or supranational government bodies.

$conomic0contract)al e1ternal stakeholders

tructural changes in the market environment make economic external stakeholders

wonder about their specific role in the competitive process. The inter-organisational

relationships among economic8contractual external stakeholders are characterised by

two forms of interaction% physical #i.e. related to the physical transfer of cargo$ and

incorporeal #"artin 2 Thomas, *++/$. The latter type of interactions consists of

contractual, supervisory or information based exchanges. The interactions between

port authorities and the first order port players are mainly of an incorporeal kind. For

instance, port companies involved in physical operations are linked to the port

authority via concession agreements #esp. in case of landlord port authority$.

There are the different port companies and supporting industries who invest directly

in the port area and who generate value-added and employment by doing so. ome of

these companies are mainly involved in physical transport operations linked to cargo

flows #e.g. terminal operators and stevedoring companies - including the

carrier8terminal operator in case of dedicated terminals$. 4thers solely offer logistical

organisation services #e.g. forwarding agencies, shipping agencies, etc...$. 'ndustrial

companies in the port area #e.g. power plants, chemical companies, assembly

plants, ..$, supporting industries #e.g. shiprepair, inspection services, etc..$ and port

labour pools also belong to the group of the first order economic stakeholders.

A large number of these in situ economic stakeholders are represented by branch

organisations and8or regional associations for specific industries. "anaging the

:

relations between different branch organisations is a challenging task. ;oth the

regional associations for specific industries as well as the existing port cluster

umbrella associations #e.g. 6eltalin<s in !otterdam and A=9A in Antwerp$ play an

important role in the governance of the port cluster and can have a huge impact on the

competitiveness of the cluster #6e >angen, *++*$.

4ther economic stakeholder groups include port customers, trading companies and

importers8exporters. They are less directly involved than the in situ economic groups

as they normally do not invest directly in the port. )evertheless they follow the port

evolution carefully, because port activity can influence their business results.

"oreover, they exert strong demand pull forces on port service suppliers and as such

,dictate- the market re<uirements to which the port community has to reply.

')2lic policy stakeholders

(conomic literature supports the idea that the public sector has its role to play in a

market-oriented port industry #cf. )otteboom 2 3inkelmans, *++/b$. A rationale for

government intervention emerges when, in certain circumstances, the competitive

market mechanism ,fails- #=oss, /77+ and 9aralambides et al, /77?$. &ractical

evidence shows that even in case of <uite extensive privatisation schemes, the public

sector has not withdrawn entirely from the port industry. The debate in (urope on

government intervention in an efficiency-oriented port industry focuses especially on

the issue of market liberalisation, the monopoly issue, the public goods issue and the

port financing issue.

&ublic policy stakeholders do not only include government departments responsible

for transport and economic affairs on a local, regional, national and supranational

level. 9ence, the scarcity of resources such as land and nature has increased the

impact and involvement of environmental departments and spatial planning

authorities on decision processes #in particular in case of port expansion plans$.

The potential overlap in jurisdiction between the various geographical levels in public

policy making is another issue that needs careful attention. A vague division of

jurisdiction or bad co-ordination among the various levels can have a detrimental

impact on port development processes, in particular when a court contests the validity

of earlier #political$ decisions because of procedural errors with respect to public

policy making.

&ublic policy stakeholders typically follow a political management system based on

the principle of distributional e<uity. The organi5ation structure in a political system

is often based on the administrative heritage and on structural shocks caused by

powerful individuals or pressure groups. &ort authorities partly rely on political

organi5ations for their survival, as ports are often considered as strategic assets in the

process of community welfare creation and as appropriate tools for achieving a higher

distributional e<uity. The challenge is for technocratic port organi5ations to work

constructively with political managers by forming alliances of effective operating

organi5ations.

1

Comm)nity stakeholders

.ommunity stakeholders include community groups or civil society organisations, the

general public, the press and other non-market players. They are concerned about the

port-s evolution, i.e. mainly about its expansion programmes, for reasons of well-

being. They pay a lot of attention both for getting and distributing information about

port activity trends and port development plans. (nvironmental considerations are

very prominent in the relationship of these groups with port authorities.

As in many organisations, community groups are often guided by local rationality and

opportunistic behaviour. >ocal pressure groups often defend their local interests in

such a fierce way that the individual well-being of a few people is becoming an even

bigger driving force than the well-being of the greater community. For instance, the

omnipresence of the )'";@ syndrome #Anot in my backyardB$ can seriously

complicate the development of new hinterland infrastructures, even if these

infrastructures will generate a positive impact on the modal shift from road to

environment friendly transport modes.

.ommunity groups can have a large impact on port city development programs. The

waterfront redevelopment of older port areas is valuable to #re$establish a physical

link between port activity and other economic functions such as housing, recreation,

etc.. . The local community typically perceives waterfront redevelopment as a positive

thing enhancing local <uality of living. &ort authorities should take such opportunity

to form a sound basis for dialogue with community stakeholders, resulting in

goodwill and mutual respect. As such, waterfront redevelopment projects can help to

activate public acceptance8awareness of seaport activity. They might even generate

more local economic benefit than the renovation of outdated port infrastructure

#outdated in the sense that draft conditions and terminal surfaces of older <uays8docks

are often too small for allowing modern transhipment activities$.

STA%$#&!$R R$&ATINS MANA3$M$NT +SRM.

Basic principles of SRM

takeholder relations management aims to hold the balance between various groups

and take due note of their rights #Argenti, /77?$. As port management is characterised

by complex decisions and is regularly confronted with many stakeholders, achieving a

balance between the interests of all stakeholders is becoming an important job for port

managers. The <uest for a port-s survival will encourage port managers to treat its

employees well, to act fairly and honourably towards port companies and port users,

and conduct itself responsibility in relation to the environment and society. "any port

managers are well aware of the fact that socially responsible behaviour can be the

basis for a competitive edge in both market and public policy relationships.

takeholder !elations "anagement has close ties with sustainable management, i.e.

sustainable port development is not possible without a well-balanced and integrated

stakeholders approach.

C

4ne of the keystones in !" in ports is to ,measure- the influence of various

stakeholders on the port-s functioning and performance and on each other and then to

effectively manage the linkages between these influential relationships.

!" in ports as such re<uires simultaneous attention to the legitimate interests of all

appropriate stakeholders, both in the establishment of organisational structures and

general policies and in case-by-case decision making. &ort managers should listen to

and openly communicate with stakeholders about their respective concerns and

contributions, and about the risks that they assume because of their involvement in

port activity and port development. 9owever, this principle does not imply that all

stakeholders should be e<ually involved in all processes and decisions.

'n a first step, port managers should discriminate between stakeholders with genuine

legitimate interests in the process considered and those who only claim to have a

legitimate interest. This exercise can turn out to be very difficult, because the simple

act of classifying a group as not relevant for a specific process #e.g. the planning of a

new port infrastructure$ in itself can become a major source for conflicts. For

instance, a party with no direct legitimate interest can have a large political influence

#e.g. a party who has the capacity to ,mobili5e- the press can have an impact on the

political level$. 'n order to avoid such situations, port managers often opt for a

maximum approach whereby both the legitimate groups and the non-legitimate

groups are invited to take part in the process. 'n many cases, the active role of the

latter groups is rather limited. The main purpose or role is that of generating

transparency in the fluxes of information.

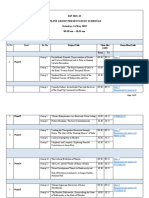

(ig)re 4: A classification of stakeholders 2ased on their involvement in and

impact on a process0decision

9igh

'nvolvement in

process8decision

>ow

>ow 9igh

'mpact on process8decision

'ource( authors

econdly, port managers will also have to decide on the role attributed to each

stakeholder in the decision-making processes. Figure * provides an example of how

?

=roups that are

taking part in

deciding

=roups that are

thinking along

=roups that

are informed

=roups that

give direction

stakeholders could be classified based on their involvement in the process8decision

and their possible impact on the process8decision.

The classification of various stakeholders in the matrix of figure * is just a first step in

a comprehensive !" process. 6esigning a well-balanced time planning for the

structuring of stakeholders- participation in port activity and development processes is

one of the key actions in !". A port authority can decide to involve all stakeholders

right from the start of a port development project. The advantage is that no

stakeholder will feel neglected. 9owever, a ,slow start- due to long pre-negotiations

rounds in the early phases of the project is the main disadvantage of this approach.

Alternatively, a port authority might decide to draw up detailed plans in-house.

takeholders will only be involved in the process once these plans have gained

maturity. The strength of this approach is that stakeholders are confronted with rather

concrete development plans, so there is less room for stakeholders to introduce

unrealistic alternatives. 9owever, some stakeholders might not feel at ease% such a

top-down approach might give the impression that the decisions have already been

taken, thereby leaving the stakeholders- participation process as a formality8diversion.

An effective !" strategy is not possible without good port governance structures

/

.

takeholder relationship management in fact partly deals with <uestions of corporate

governance, i.e. mainly the processes of stakeholder input and participation. The

corporate governance framework should recognise the rights of stakeholders and

encourage active co-operation and participation of stakeholders in creating wealth

#;rooks, *++/$.

&ort authorities should develop organisational processes and entrepreneurial cultures

that enhance stakeholder satisfaction. &ort managers today have the obligation to deal

openly and honestly with the various stakeholders, thereby avoiding as much as

possibly purely self-serving actions. 'n modern port policy and the decision making

processes one should emphasise the interdependence among the various stakeholders.

&ositive and mutually supportive stakeholder relationships will encourage trust, and

stimulate collaborative efforts leading to relational wealth, i.e. organi5ational assets

arising from familiarity and teamwork. .onflict and suspicion among stakeholders

will stimulate formal bargaining resulting in time delays and increased costs. Formal

bargaining often appears when stakeholders demand compensation for incurred risks

or harms. &ort managers should work cooperatively with other entities, both public

and private, to insure that risks and harms arising from port activities are minimi5ed

and, where they cannot be avoided, appropriately compensated. .onse<uently,

compensation policies often play a crucial role in !" #in particular in relationship to

community groups$. Dnfortunately, in many cases, compensation claims are subject to

highly politicised negotiation rounds, characterised by a lack of trust and an absence

of solid deals8arrangements among the stakeholders. Dnder these circumstances port

authorities and government departments might be tempted to use compensations as a

tool to ,neutrali5e- #at least temporary$ some community groups, whereas community

/

;rooks #*++/$ refers to the 4(.6 definition of corporate governance% ,the system by which business

corporations are $irecte$ an$ contro!!e$. The corporate )overnance structure specifies the $istribution

of ri)hts an$ responsibi!ities amon) the $ifferent participants in the corporation, such as the boar$,

mana)ers, shareho!$ers an$ sta"eho!$ers, an$ spe!!s out the ru!es an$ proce$ures for ma"in)

$ecisions on corporate affairs. *y $oin) so, it a!so provi$es the structure throu)h which corporate

ob+ectives are set, an$ the means of obtainin) those ob+ectives an$ monitorin) performance-.

E

groups might use the negotiations rounds as a tool to consolidate their position as

legitimate interlocutors in port development debates.

SRM and the port management o25ective str)ggle

&ort managers should acknowledge and whenever possible actively monitor the

concerns of all legitimate stakeholders, i.e. they should take the interests of certain

stakeholders appropriately into account in decision-making and operations. They are

obliged to examine all claims and criticism carefully before passing judgment on their

validity. 'n taking particular decisions and actions, port managers should give primary

consideration to the interests of those stakeholders who are most intimately and

critically involved.

This balancing exercise is far from easy, given the latent danger of a struggle between

port management objectives as a function of group interests. The underlying common

interest of stakeholders of any port is the port-s survival, but it is too simplistic to

assume that all parties accept that the main port development objective is ,to provide

port facilities and operating systems in the national interest at the lowest combined cost

to the port and port users- #D).TA6, /7E1%*?$. .onflicts of interests among different

stakeholders may overshadow the community of interests #see figure 0$. The

objectives of port authorities are becoming increasingly scrutini5ed as a result of

government involvement as well as increased complexity of the industry and its

environment #Frankel, /7E?$. ome examples%

The final or primary objectives of environmental pressure groups are often

conflicting with that of the port authority% for the one the less expansion the better,

for the other almost continuous extension is re<uired to cope with market

opportunities in the foreland-hinterland continuumF

The central government usually pursues socio-economic objectives, aimed at an

increase of the societal value-added of the national seaport system through an active

seaport policy. The aim to increase national socio-economic welfare may in practice

be influenced by a number of economic and political considerations #Frankel, /7E?$.

Through their port policy, some larger (uropean countries for example also aim at

increasing the national control of foreign trade. As most 3est-(uropean central

governments intervene in seaport policy, through the allocation of resources in

function of objectives related to socio-economic welfare, the central government

objectives may conflict with or at least diverge from objectives of the port authorityF

The objectives of the port industries and operators usually relate to traditional micro-

economic goals such as a mix of shareholder value, maximi5ation of profits, growth,

increase in market share, productivity, etc.. .

7

(ig)re 6: The port management o25ectives str)ggle +7.

#G$ Tentative representation of main objectives per category of stakeholders in order to detect potential

conflict situations

&ort authorities do not always have explicitly specified objectives nor do they have a

good defendable strategic intent. "unicipal ports may be instructed to provide the

community with the best possible port service that is consistent with the municipal

policy and financial capability.

The lack of clearly specified ambitions or a clear mission statement makes it

extremely difficult to develop sustainable stakeholders relationships. As such, it might

be very important to formulate accurately a mission statement for the whole port. 'n

formulating its strategic intent a port should try to go beyond extrapolation of the

current role of the port. A good mission statement can help to avoid wasting resources

due to the port management objectives struggle #3inkelmans, *++*$. The port-s

ambition as specified in the strategic intent must be accepted by internal and external

stakeholders. &ersonal effort and commitment of the stakeholders involved in the port

sector can only be gained if they can identify themselves with the strategic intent.

ince the formulation of a comprehensive and effective mission statement generates a

positive commitment under the most concerned actors, it might help to achieve the

goal of competitive advantage. A good mission statement always should contain a

clear message toward the stakeholders of the company8organisation formulating the

strategic intent. This message should be valid and controllable.

0r +b1ective Rating 2ctor )omment Rating

3 ma-imise throughput #+RT 2*T4+RIT5 conlict 6 7

8 ma-imise net proits S4I##I09 LI0E

" operate at least cost S4I##I09 LI0E

$ ma-imise employment level *0I+0S

: secure national independence

as regards matitime transport

9+;ER0ME0T

< promote regional economic development 9+;ER0ME0T

= ma-imise >uality o service to shippers #+RT 2*T4+RIT5

7 minimise vessel/s time in port #+RT 2*T4+RIT5 conlict 6 3

? reach inancial autonomy 2LL

3@ minimise total cost o maritime transport S4I##ERS conlict 6 3<

33 ma-imise return on capital invested #+RT 2*T4+RIT5

38 minimise re>uired capital investments 9+;ER0ME0T conlict 6 3"

3" ensure ull environmental protection #RESS*RE 9R+*# conlict 6 38

3$ minimise port user cost S4I# +(0ER

3: minimise cargo delays S4I##ERS

3< ma-imise pay levels *0I+0S conlict 6 3@

3= A

/+

!$8$&'M$NTS A(($CTIN3 STA%$#&!$R R$&ATINS

MANA3$M$NT

The increasing need for effective stakeholder relationship management is a fairly

normal development given the globalisation and liberali5ation of economy. These

structural changes are pushing seaports to deal with new kinds of social, political and

economic stakeholders in a different way. As such, !" will prove to be a keystone

in a port-s functioning and development.

4n the one side the expansion of the role of the private sector in port activities has

forced ports to become more market-oriented. 4n the other hand non-market forces

still exist. 6espite the growing market and customer orientation the non-market

environment remains important. =overnment interventions at different levels as well

as external pressure groups such as the ecological pressure groups may still interact

without incurring the demand for efficiency #e.g. think of the non-market force

incurring severe delays on the implementation of the dredging program for the port of

)ew @ork and )ew Hersey by so-called IgreenI actions$.

This section points to some developments in the port environment that need special

attention in the framework of !". The list of issues raised is not complete, but it

provides a first step towards further discussion and research in this field.

Integration at the level of market players

A lot of market players in the foreland-hinterland continuum aim to integrate either

vertically or hori5ontally all kinds of activities to reduce costs, to improve efficiency

and by doing so to deliver value and a ,one-stop shop- service to the customer.

The observed vertical integration strategies of the market players have blurred the

traditional division of tasks within logistic chains. For instance, the (uropean

stevedoring market is witnessing an influx of new entrants including railway

companies #e.g. ;elgian !ail$, shipping lines #e.g. dedicated terminals of "aersk

ea>and in ;remen, Algeciras and !otterdam$, logistics companies and investment

groups. A lot of shipping lines, stevedoring companies and transport operators are

now offering forwarding services to the customer. Freight forwarders no longer act as

agents of the shipper, but are principals in their own right. !oad hauliers have in

many countries become professional service providers with whom the shipping line or

the shipper can outsource part or all of its inland distribution operation #)otteboom 2

3inkelmans, *++/$. 't is important to add that the provision of integrated services

does not always need to coincide with the ownership of the related assets. 'n many

cases, the integration is achieved through close partnerships with other players.

This integrated approach has created an environment in which ports are increasingly

competing not as individual places that handle ships but as nodal points within a

complex of supply and demand chains, including various transport chains. 3hile co-

operation at the operational level between the actors in the supply chain may have

increased, this has not necessarily resulted in increased commitment to a long-term

future relationship with the port. 'n this competitive environment, the ultimate success

of a port will depend on the ability to integrate the port effectively into the networks

//

of business relationships that shape supply chains. 'n other words, the success of a

seaport no longer exclusively depends on its internal weaknesses and strengths. 't is

more and more being determined by the ability of the port community to fully exploit

synergies with other nodes and other players within the logistics networks of which

they are part.

'n terms of stakeholder management this observation does not only imply that the port

authority will have to manifest itself as an important stakeholder to others. 't also

means that port authorities will have to consider more market-related external

stakeholders than ever before. At the same time, port managers will increasingly

encounter new challenges while identifying and classifying the relevant stakeholders.

For instance, it is no longer straightforward to make a keen distinction between port

suppliers and port demanders. 'f a shipowner operates a dedicated terminal (here

defined as a port terminal that has been reserved by the port authority for a single port

user or shipowner$, it is becoming less clear who is then the basic port customer, since

the shipping company itself is taking care of the re<uired port #cargo$ handling

capacity. 'n addition we should notice, that due to the many vertical and hori5ontal

integrations in the maritime industry #including the so-called strategic alliances$ fewer

but bigger players are intervening, i.e. using the new interplay of forces, and as such

are creating new challenges in the framework of port development and management.

The emergence of powerf)l players

&ort managers aim at making the port attractive to users, by providing a competitive

supply of services for carriers and shippers. 9owever, several ports are becoming

increasingly dependent on external co-ordination and control by #foreign$ actors who

might extract a substantial share of the economic rent #wealth$ produced by ports and

who are often only guided by the aim of creating a maximum shareholder value.

=iven the increasingly footloose character of #maritime$ traffic, it might be

inappropriate for a port trying to keep this kind of traffic at any cost. 'f powerful

actors in a specific logistics chain exert strong pressure on a port, because of

economic rent generated elsewhere in the chain, it might be wise for the port to ,opt

out- of this chain. For instance, the port community is rarely involved in load centring

decisions of shipping lines. 9owever, many of the costs arising out of hub selection

are borne by the #port$ community #lack, /77+$. The port-s ability to raise tariffs,

even when justified by rising costs, is very limited as a function of concrete market

considerations. 'f the costs and benefits of achieving hub status cannot clearly be

distributed e<ually between shipping lines and ports, the position of the port is no

longer sustainable.

The increasing bargaining power of some market players #in particular shippers and

carriers$ undoubtedly will reshape the relationships with port authorities and even

with the government. &owerful market players will more and more step to the

foreground as direct interlocutors not only on the operational level of port activity, but

also in strategic matters related to port planning and port policy. They will more than

ever establish the base lines for pricing. All this will certainly have an effect on the

necessary stakeholder relationship management.

/*

The increased bargaining power of some market players is clearly illustrated by

looking at the concept of a dedicated terminal. ;y means of dedicated terminal

shipping companies can establish port infrastructure at their own expense #cf. e.g.

"aersk ealand in Algeciras, ;remen and !otterdam$. This may create <uite specific

legal problems with regard to property law and the territorial competence of the

public port authority. An important issue in this context is the <uestion whether the

port operator-user in possession of a dedicated terminal holds a dominant position. 'n

general terms, a dominant position means that a player is able to prevent effective

competition in the marketplace due to the fact that he can act largely independently

from competitors and customers, and ultimately from consumers too #9uybrechts et

al, *++*% /*1$. 't all depends on the substitutability of the facility, whence - once

again - the importance of applying !" in order to avoid conflicting #c.<. dominating

or abusing$ situations.

The distri2)tion of 2enefits and costs related to ports

The external spill-over effects of ports never have been greater. At the same time, the

economic effects of seaport activities are no longer limited to the local environment

#i.e. the port region and the local market players$, but are spread over a much wider

geographical area and among a large number of international players. 'n other words,

the economic benefits of port activities are expanding from the local port system

towards a much larger economic system #;enacchio 2 "usso, *++/$.

The geographical dispersion of economic effects is very apparent when a port does

not concentrate on developing local value-added activities linked to transit cargo

#intermediacy-based as well as centrality-based flows$ or on establishing a strong

local industrial and logistic cluster. 'n that case cargo flows are just passing without

generating a lot of employment and value-added for the local community. The

changing distribution of benefits is also illustrated by the development of logistics

5ones in the vicinity of seaports or in inland locations along the main corridors

towards the hinterland #supported by growing containerisation and inter-modality$.

These logistics sites and 5ones in many cases generate considerable economic effects

by providing low-end and high-end value-adding logistic activities and only use large

load centres as a transit point for their cargo. )evertheless, it is <uite unlikely that

these sites and 5ones would have developed were it not for the presence of seaports.

For example, the functional interactions between the ports of Antwerp, !otterdam and

logistics 5ones in the hinterland have created a large logistics pole. Antwerp and

!otterdam are the central nodes driving the transport dynamics in this logistics pole.

;ut at the same time Antwerp and !otterdam rely heavily on the hinterland nodes to

preserve their attractiveness #)otteboom, *+++$.

The benefits tend to become less concentrated in the local port region but at the same

time negative side-effects of port activities are primarily felt at the local level.

/0

A large part of the population takes seaports for granted and is woefully ignorant of

how the port is organi5ed and operated and to what extent the port contributes to the

local economy

*

. "ore attention is given to the fact that the growth of a port in many

cases goes hand in hand with increasing negative effects for the local community,

such as road congestion, intrusion of the landscape, noise and air pollution and the use

of scarce land. ome community groups argue that there is a clear imbalance between

the benefits and costs for the local community of having larger and larger ports. This

viewpoint is a breeding ground for major socio-economic confrontations related to

port development.

'n view of developing sustainable stakeholder relations, port managers and

government bodies nowadays #have to$ spend a lot of time in trying to make sure that

new port developments are socially broadly based. &orts cannot and must not take

broad public support for development plans for granted. This aspect of port

competitiveness will undoubtedly become more important in the near future as

resources such as land are becoming scarcer and as broader social and environmental

functions are challenging the economic function of seaports. The more international

the maritime and port industry becomes, the more energy will have to be put in

embedding the port in the local community.

The increasing press)re on local reso)rces

&orts use resources in order to consolidate their position in worldwide logistic and

transport networks. The <uestion remains whether the local community is getting a

fair input payback for the scarce local resources used for creating economic rent. For

instance, land for new port developments has become very scarce. )evertheless, land

sites for port activities are sometimes ,sold- on the market for less than their intrinsic

value. ;y doing so, port managers hope to attract new clients. 4nce a new port client

starts operations, the less than correct input payback for port land would be

compensated abundantly by value-added creation #local employment, investments,

taxes and profits$. 9owever, one has to keep in mind that many powerful port users

are extracting a large part of the economic rent produced by ports, so the issue of a

correct input payback for the local system remains a tricky one.

takeholder relationship management should take into account the increasing pressure

on local resources. &ort authorities should make the relation between the price for

scarce resources on the one hand and the socio-economic payback on the other more

transparent both to port users and community groups. >ack of transparency feeds the

suspicion among port companies and clients on the existence of price discriminating

behaviour in favour of some companies #e.g. in terms of land lease agreements or port

dues$ and might lead to harmful socio-economic confrontations in this field.

*

ometimes ports like to overestimate their economic impact. The <uestion is not that ports add

economic value J but, given the level of economic subsidy, could there have been more economic

value created by an alternative deployment of the subsidy K The answer to this kind of <uestion is far

from straightforward. There might be industries with higher value-added per invested or subsidi5ed

unit, but the high returns in such industries in many cases partly relies on the performance of a port

system that takes care of cargo handling and logistics.

/:

Investments in port infrastr)ct)re

(conomic theory proves that optimal working conditions only exist when a fairly

good e<uilibrium exists between supply and demand. Achieving such an e<uilibrium

in real world conditions never has been an easy task.

'n the past, most (uropean governments have predominantly funded the majority of

large infrastructure works in (uropean container ports. These governments now want

to curb their financial participation in terminal development projects as they face

declining available funds. "oreover, this development is enhanced by the (uropean

.ommission-s statement that the assumed high level of distortions in (uropean inter-

port competition results from public interventions #including subsidies for port

infrastructures$ at the national and sub-national levels in various (D "ember tates.

The expected gradual withdrawal of governments in the financing of terminal

infrastructure might confront even the largest and most prosperous ports in (urope

with severe financial pressures to keep their competitive edge.

(ven with the current rise of self-financing investors in port infrastructure #being

autonomous public port authorities$ it remains extremely difficult to install a

comprehensive port capacity regulation and to lower the apparent danger of structural

overcapacity. 't is more than an open <uestion whether port authorities will take

action to co-ordinate their ambition in capacity #building$ with other ports or whether

it will be primarily up to the market mechanism to reduce overcapacity.

The changes to be expected in the way port infrastructures are financed, urgently

re<uire reconsideration of the many stakeholder relationships, i.e. with governments

and shareholders, with primary economic stakeholders and the indirect or community

stakeholders as well. "uch of the port policy debate in (uropean countries is directed

toward the establishment of effective relationships between the private port industry,

public or private port authorities and central government.

SM$ R$(&$CTINS N SRM IN T#$ (&$MIS# 'RT

S9ST$M

The 'ort !ecree as a tool for SRM among port a)thorities

The seaport system of Flanders consists of four ports% Antwerpen, Leebrugge, =hent

and 4stend. Total cargo throughput in *++/ amounted to some /7+ million tonnes of

which /0+ million was generated in the port of Antwerp. The Flemish port authorities

operate basically as landlords. 'n recent years, their position and role has changed as a

result of developments on the international markets, including a general concentration

in the maritime container transport sector, greater port volatility on the part of

container shipping companies, the allocation of dedicated terminals in competing

ports, etc.. .

The former instant fights for public support between the ;elgian #since /77+ Flemish$

government and among the four Flemish port authorities has come to an end by

structuring the relationships between port authorities and governments in the

/1

framework of the &ort 6ecree #"arch *

nd

of /777$. The &ort 6ecree has moved the

Flemish ports towards full corporatisation. The decree covers the rules and conditions

for a higher managerial autonomy for each Flemish port, via a shift towards an

independent legal status. As a result the public port authorities have been transformed

towards a more autonomous status. Although port authorities still have strong ties

with their respective municipalities through the ownership structure, decision in the

last three years are made on an independent basis and port managers are accountable

for these decisions.

The &ort 6ecree-s objectives are e<ual working conditions for the Flemish ports, the

creation of clear and transparent relationships among Flemish ports and some general

guidelines with respect to investments in port infrastructure and maritime access

routes #Flemish &ort .ommission, /77E and /777$. The final aim is the creation of an

independent port management system with a sound commercial strategy - including

the possibility to diversify in other ports or activities via financial participation - and

full accountability for the results of administrative and operational activities

#3inkelmans 2 &oelvoorde, /77:$.

The &ort 6ecree not only promotes better port governance structures, it also gives

each port authority more space to develop its stakeholders relationship management

autonomously, under more or less e<ual starting conditions as the other Flemish ports.

't is still too early to measure the full impact of the &ort 6ecree and associated port

management reorganisation on the competitiveness and governance structure of the

Flemish seaports. 4ne of the conse<uences of this new port policy framework is that

all four Flemish seaports are clearly in speaking terms about co-operation much more

than ever before. The Flemish &orts .ommission has carefully built the foundations in

this field. ince /77+ this commission indeed has made several recommendations

regarding ,the establishment of long term port strategy- #/77*$, ,port subsidisation-

#/77*$, ,port management- #/77*$, ,a first draft of port decree- #/770$, ,toward a new

port policy and management- #/770$, ,about strengths and weaknesses of the Flemish

ports- #/77?$, ,on financing port investments- #/77?$, and ,about strategic port

planning- #*++*$.

The (lemish 'orts Commission as a stakeholders meeting point

The &ort 6ecree of the Flemish government includes paragraphs on the role of the

Flemish &orts .ommission as an interface between the public administration of ports,

the port authorities and the #trans$port industry in the renewed policy framework and

the changing market environment.

The current composition of the Flemish &orts .ommission is depicted in Figure 0.

/C

(ig)re 6: Composition of the (lemish 'orts Commission as from 4::*

'ource( the authors, own representation

>egend% formal relationships informal #informative$ relationships

The compositional structure of the F&. is rather original in the sense that #/$ neither

public departments8ministries nor external experts can exert any direct influence on

the decision making process of the commission, #*$ the port authorities never possess

a majority of votes - even if they exceptionally would all fully agree, and #0$ strategic

and administrative confrontations are fostered in view of gaining a sound balance in

potentially conflicting interests. The majority of votes belongs to representatives of

trade unions and employers, not to those who are directly involved in #or committed

to$ one specific port. These representatives are indeed expected to consider port

policy, port development and management not as the final aim but as means to

enhance regional and societal welfare. The civil servants from various relevant

ministries, who are expected to act in the same direction, however are expected to

inform their relevant minister#s$ of transport #infrastructure$ and mobility, and as such

they can be asked J whenever considered necessary - to inform the .ommission,

which will then come to its own conclusions under the form of advice or a

recommendation to its minister. 'f this recommendation is formulated by unanimity

/?

Board of

Ministers

Minister o

#ublic (orks' Transport

and

Spatial #lanning

Bepartment o

Maritime Transport

and Seaport

#ort

2utorities !33%

Representatives

o Inland !"%

Transport Modes

(&$MIS#

'RT +6:.

CMMISSIN

E-ternal

e-perts

Representatives

o trade unions !7%

Representatives o

Employers !7%

(orking group

port

pro1ects

(orking group

competition C

management

Board of

Ministers

Minister o

#ublic (orks' Transport

and

Spatial #lanning

Bepartment o

Maritime Transport

and Seaports

#ort

2uthorities !33%

Representatives

o Inland !"%

Transport Modes

(&$MIS#

'RT +6:.

CMMISSIN

E-ternal

e-perts

Representatives

o trade unions !7%

Representatives o

Employers !7%

(orking group

port

pro1ects

(orking group

competition C

management

EXECUTIVE

BOARD

then the minister is compelled to follow it. 9e or she is also compelled to ask for

advice whenever the #port$ project involves public means of more than /+ million M.

6uring its rather short period of existence F&. succeeded in producing a whole series

of advices, recommendations and reports, which have had a very positive influence.

ince the installation of F&., port authorities show less opportunistic behavior and

local rationality when port #extension$ projects are at stake. The confrontation of

ideas, proposals and plans in the bosom of the F&. finally have created a constructive

climate and a growing mutual understanding, esp. with respect to the existence of

many common interests in the field of the ever changing maritime world.

At the moment a series of strategic plans for every seaport in Flanders are at stake. 'n

accordance to the proposed stakeholders approach it should become very clear that

economic and ecological reasoning is to be compromised. The best way to come to

consistent and coherent conclusions is to start from a well understood long term

strategic vision and to integrate as much as possible into the debate the relevant

shareholder and stakeholder visions

. uch strategic studies are to be fulfilled neither top-down nor bottom-up, they

should reflect the so-called goals-down, planning-up approach. Top-down planning

typically results in incoherent compilations of local port plans. ;ottom-up planning at

first sight looks more promising, but due to local rationality and opportunism macro-

and socio-economic objectives are under pressure. The ,goals down - plans-up-

approach is to be preferred. 'n that case the government e.g. proposes to define first of

all the Astrategic intentsB in collaboration with the individual ports concerned and asks

the port authorities and port industry to come up with their own strategic plans that

comply with this intent. 'n view of getting the necessary structured strategic and

administrative confrontations, the government can establish a coordinating body. The

final aim is to achieve a dynamic balance between on the one hand macro-economic

objectives and on the other hand micro-economic goals. &ort operators and port

authorities are no doubt the core actors in the development of specific port projects,

nevertheless other stakeholders - amongst which the government - play a very

important role and therefore should get a full but well-structured opportunity to fulfil

their role in the interplay of forces and to ensure that essential macro-economic goals

are not neglected.

;y means of a well-structured !" a wider socially relevant port planning can be

achieved. 'n that case the port could find out how to defend and how to bring into

operation the thesis, that not only well-being, but the degree of welfare too is

important as a focus in achieving sustainable development.

A result of !"-activities could be that the strategic port planning process could

include a new kind of studies, i.e. an A'(!-studyB #'nfrastructure (ffect !eporting$ in

addition to the classical A"(!-studyB #(nvironmental (ffect !eporting$. 'ndeed, both

the protection of the environment and the re<uirements of infrastructure are today

affected by considerations of scarcity and the concepts of public good and merit good.

'n ;elgium more than one port project is hampered by the sudden application of new

environmental regulations #e.g. the habitat and bird regulations$ even in cases where it

concerns port areas, which have been reserved for port extension since long ago.

Apparently the possible mutual interests J of the port in terms of space needs and of

/E

the community in terms of safeguarding free spaces - are not finding any hearing so

far. This might be due to the non-existence of any good !" policy in the context of

port development.

CNC&"SINS

A port both technologically and economically is a node for contacts and contracts,

whereby a multitude of individuals and interests #should$ collaborate for the creation

and distribution of wealth. &ort managers should carefully take into account that new

politico-economic situations exist, which make the success of a port no longer

dependent exclusively on its own performances. "any other #f$actors and situations

determine a port-s success, including

pro-active behaviour of environmentalists, the non-expert vision on port extensions

by N men in the street O, etc.

The <uest for a port-s survival will encourage port managers to develop takeholder

!elations "anagement tools that allow them to treat the employees well, to act fairly

and honourably towards port companies and port users, and to conduct responsible in

relation to the environment and society.

Peystones in !" include the identification and classification of internal and

external stakeholders, the measurement of the influence of various stakeholders on the

port-s functioning, the management of the influential relationships with stakeholders

and the development of appropriate time plans for the structuring of stakeholders-

participation in port activity and development processes.

ome developments in the port environment urge a well-balanced !". These

developments are related to hori5ontal and vertical integration at the level of market

players, the emergence of powerful players, changes in the distribution of benefits and

costs related to port activity, the increasing pressure on local resources and the

investment issue in port infrastructure.

This discussion paper did not provide the reader with straight answers to all aspects of

!". 't should therefore be regarded as a step towards further research in this field

on a case-by-case basis.

&IST ( R$($R$NC$S

A!=()T', H., /77?, takeholders% the case against, -on) .an)e P!annin), 0+#0$, ::*-::1

;()A..9'4, "., "D4, (., *++/, &orts and (conomic 'mpact% main changes,

assessment approaches and distribution dise<uilibrium, Transporti Europei #Quarterly Hournal

of Transport >aw, (conomics and (ngineering$, ? #/?$, *1-0C

6( >A)=(), &., *++*, Port competitiveness an$ c!uster )overnance, presentation at the

'T""A conference ,&ort competitiveness-, Antwerp, February 1, *++*

/7

64)A>64), T., &!(T4), >.(., /771, The stakeholder theory of the corporation%

concepts, evidence and implications, Aca$emy of Mana)ement .eview, *+ #/$, C1-7/

F>("'9 &4!T .4""''4), /77E, Annua! .eport, ;russels, (!R

F>("'9 &4!T .4""''4), /777, Annua! .eport, ;russels, (!R

F!A)P(>, (.=., /7E?, Port P!annin) an$ #eve!opment, )ew @ork, Hohn 3iley and ons

=4, !. /77+, (conomic policies and seaports - part 0% Are port authorities necessary K .

Maritime Po!icy an$ Mana)ement, /?, *1?-*?/

9A!A>A";'6(, 9.(., "A, ., R(()T!A, A.3., /77?, 3orld-wide experiences of port

reform. 'n% "eersman, 9., Ran de Roorde, (. #ed$ Transformin) the port an$ transportation

business. >euven, Acco, /+?-/:0

"A!T'), H., T94"A, ;.H., *++/, The container terminal community, Maritime Po!icy an$

Mana)ement, *E#0$, *?7-*7*

"'>>, !., 3(')T('), ;., *+++, ;eyond shareholder value J !econciling the hareholder

and takeholder perspectives, /ourna! of 0enera! Mana)ement, *1 #0$, pp. ?7-70

)4TT(;44", T., 3')P(>"A), 3., *++/, tructural changes in logistics% how will port

authorities face the challengeK, Maritime Po!icy an$ Mana)ement, *E #/$, ?/-E7

)4TT(;44", T., 3')P(>"A), 3., *++/b, !eassessing public sector involvement in

(uropean seaports, Internationa! /ourna! of Maritime Economics, * #0$, p. *:*-*17

9A)P"A), ).A., /777, !eframing the debate between agency and stakeholder theories of

the firm, /ourna! of *usiness Ethics, /7, pp. 0/7-00:

>A.P, ;., /77+, 'ntermodal transportation in )orth America and the development of inland

load centres, Professiona! 0eo)rapher, :*#/$, pp. ?*-E0

D).TA6, /7E1, Port #eve!opment( A 1an$boo" for p!anners in $eve!opin) countries, )ew

@ork.

3')P(>"A), 3., )4TT(;44", T., /77:, Ports as no$a! points in a 0!oba! Transport

'ystem, paper presented at ("'&-7:, !otterdam, *: Hune /77:, // p.

3')P(>"A), 3., *++*, trategic eaport &lanning% in search of core competency and

competitive advantage, Ports an$ 1arbors, 'A&9, April *++*, :?#0$, /?-*/.

3')P(>"A), 3., &4(>R44!6(, (., /77:, &ort !eforms in ;elgium, a earch into

)ew "anagement tructures and 6ecision &rocedures, Maritime Transport an$ -o)istics in

the New Europe #(d. Dniversity of =dansk$, =dansk, /11-/E/.

*+

This paper is part of the

IAME Panama 2002 Conference Proceedings

The paper has been anonymously peer reviewed and accepted for presentation by the

'A"( &anama *++* 'nternational teering .ommittee

The conference was held on

1 ! 1" #o$em%er 2002

in Panama

The complete conference proceedings are published in electronic format under

http%88www.eclac.cl8Transporte8perfil8iameSpapers8papers.asp

For further information contact jhoffmannSeclacTyahoo.com

*/

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Cover Letter TourismDocumento2 pagineCover Letter TourismMuhammad IMRANNessuna valutazione finora

- Airport Privatization FinalDocumento15 pagineAirport Privatization FinalSombwit KabasiNessuna valutazione finora

- Red Line TransportDocumento8 pagineRed Line TransportBasri JayNessuna valutazione finora

- Why Bharat Matters Mapping Indias Rise As A Civilisational StateDocumento2 pagineWhy Bharat Matters Mapping Indias Rise As A Civilisational Statevaibhav chaudhariNessuna valutazione finora

- Outsourcing Strategies ChallengesDocumento21 pagineOutsourcing Strategies ChallengesshivenderNessuna valutazione finora

- UNCTAD Financing Port DevelopmentDocumento28 pagineUNCTAD Financing Port DevelopmentGervan Sealy100% (1)

- The Political Strategies of The Moro Islamic LiberDocumento26 pagineThe Political Strategies of The Moro Islamic LiberArchAngel Grace Moreno BayangNessuna valutazione finora

- Protection of Rights of MinoritiesDocumento15 pagineProtection of Rights of MinoritiesanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Voice of Customer Robert Cooper PDFDocumento13 pagineVoice of Customer Robert Cooper PDFBiYa KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Bias and PrejudiceDocumento16 pagineBias and PrejudiceLilay BarambanganNessuna valutazione finora

- Transportation's Role in Economic DevelopmentDocumento10 pagineTransportation's Role in Economic Developmentsooraj_c_nNessuna valutazione finora

- (Palgrave Studies in Maritime Economics) - Sustainable Port Clusters and Economic Development PDFDocumento195 pagine(Palgrave Studies in Maritime Economics) - Sustainable Port Clusters and Economic Development PDFAnouck PereiraNessuna valutazione finora

- Harnessing urbanization to end povertyDocumento18 pagineHarnessing urbanization to end povertyNikhil SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Papers On Port AutomationDocumento22 paginePapers On Port AutomationSrikanth DixitNessuna valutazione finora

- Skills Training on Catering Services cum Provision of Starter KitDocumento4 pagineSkills Training on Catering Services cum Provision of Starter KitKim Boyles Fuentes100% (1)

- Competition Excess Capacity and The PriceDocumento25 pagineCompetition Excess Capacity and The PriceAli Raza HanjraNessuna valutazione finora

- The Future of AirportsDocumento7 pagineThe Future of AirportsBrazil offshore jobsNessuna valutazione finora

- Tanjung Priok, Jakarta - Research Report RVO - Malabon ContextDocumento36 pagineTanjung Priok, Jakarta - Research Report RVO - Malabon ContextJed BonbonNessuna valutazione finora

- 4globalisation, Privatisation and Restructuring of PortsDocumento36 pagine4globalisation, Privatisation and Restructuring of PortsAhmad FadzilNessuna valutazione finora

- Master Thesis on London-Piraeus maritime network and APS providersDocumento97 pagineMaster Thesis on London-Piraeus maritime network and APS providersDaniela DuşaNessuna valutazione finora

- Value Creation Through Corporate Sustainability in The Port Sector: A Structured Literature AnalysisDocumento17 pagineValue Creation Through Corporate Sustainability in The Port Sector: A Structured Literature Analysissita deliyana FirmialyNessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento14 pagineUntitledTammam HassanNessuna valutazione finora

- Journal of Transport Geography: Patrick Witte, Brian Slack, Maarten Keesman, Jeanne-Hélène Jugie, Bart WiegmansDocumento11 pagineJournal of Transport Geography: Patrick Witte, Brian Slack, Maarten Keesman, Jeanne-Hélène Jugie, Bart WiegmansJordan DavisNessuna valutazione finora

- Reginal ScienceDocumento6 pagineReginal SciencegermanNessuna valutazione finora

- International Business Project: Made By-Sonali Malhotra Tybbi Roll No: 35Documento10 pagineInternational Business Project: Made By-Sonali Malhotra Tybbi Roll No: 35sonali_15Nessuna valutazione finora

- 10 Annual Australasian Summit Ports, Shipping and Waterfront ReformDocumento3 pagine10 Annual Australasian Summit Ports, Shipping and Waterfront Reformaccount_meNessuna valutazione finora

- The Port City InterfaceDocumento8 pagineThe Port City InterfaceNadia AndaliniNessuna valutazione finora

- Barcelona Port's Economic ImpactDocumento3 pagineBarcelona Port's Economic ImpactAbigail FrazierNessuna valutazione finora

- ownership structure&financial performance of firmDocumento26 pagineownership structure&financial performance of firmTaiwo JosephNessuna valutazione finora

- Sustainability 11 04542 v2Documento20 pagineSustainability 11 04542 v2Đặng Thế HùngNessuna valutazione finora

- Piraeus Port and City: A Comprehensive Analysis of Correlations and DependenciesDocumento16 paginePiraeus Port and City: A Comprehensive Analysis of Correlations and DependenciesIJAR JOURNALNessuna valutazione finora

- Assignment For Accounting For MBA CandidateDocumento13 pagineAssignment For Accounting For MBA Candidatenm zuhdiNessuna valutazione finora

- Tactical Urbanism With Pattern Language Toolkits-MehaffyDocumento11 pagineTactical Urbanism With Pattern Language Toolkits-MehaffyLeif BreckeNessuna valutazione finora

- Impact of Autonomous Ships on Supply Chains and Shipping OperationsDocumento7 pagineImpact of Autonomous Ships on Supply Chains and Shipping OperationsSamia UsmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Importance of Port Location for Trade and EconomyDocumento6 pagineImportance of Port Location for Trade and EconomyLogesh RajNessuna valutazione finora

- 29 Santo Building A Common Aviation AreaDocumento3 pagine29 Santo Building A Common Aviation AreaW.J. ZondagNessuna valutazione finora

- Thompson SummaryDocumento18 pagineThompson SummaryjsmnjasminesNessuna valutazione finora

- Literature Review On Shipping IndustryDocumento4 pagineLiterature Review On Shipping Industryc5ngamsd100% (1)

- ALLAM Y JONES Attracting Investment by Introducing The City As A Special Economic ZoneDocumento8 pagineALLAM Y JONES Attracting Investment by Introducing The City As A Special Economic ZoneDiego RoldánNessuna valutazione finora

- Economics of Sea TransportDocumento495 pagineEconomics of Sea TransportsinisterlyleftyNessuna valutazione finora

- Ferro 2014 para TransitDocumento44 pagineFerro 2014 para TransitKarol GalvánNessuna valutazione finora

- European Port Cities in Transition: Moving Towards More Sustainable Sea Transport HubsDa EverandEuropean Port Cities in Transition: Moving Towards More Sustainable Sea Transport HubsAngela CarpenterNessuna valutazione finora

- Port Administration: Public Vs Private Sector John Lethbridge and Zvi Ra'ananDocumento3 paginePort Administration: Public Vs Private Sector John Lethbridge and Zvi Ra'ananbinary786Nessuna valutazione finora

- 2010 MPM VaggelasPallisDocumento26 pagine2010 MPM VaggelasPallisDita HasanahNessuna valutazione finora

- Keeping ship agents and ship brokers up to pace with digitalizationDocumento5 pagineKeeping ship agents and ship brokers up to pace with digitalizationMai PhamNessuna valutazione finora

- Sustainability: AbstractDocumento21 pagineSustainability: AbstractMoazzam TiwanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Peri-Urbanization - Zones of Rural-Urban TransitionDocumento10 paginePeri-Urbanization - Zones of Rural-Urban TransitionVijay Krsna100% (1)

- Dunning CityLondonCase 1969Documento27 pagineDunning CityLondonCase 1969agovilNessuna valutazione finora

- 2016 Erasmus UsaDocumento27 pagine2016 Erasmus UsaPantazis PastrasNessuna valutazione finora

- Agglomeration and Crossborder InfrastructureDocumento27 pagineAgglomeration and Crossborder InfrastructureHighSpeedRailNessuna valutazione finora

- Competitiveness K: Brought To You by The Glorious GJJP LabDocumento64 pagineCompetitiveness K: Brought To You by The Glorious GJJP LabBen Alexander WrightNessuna valutazione finora

- Freight VillageDocumento3 pagineFreight VillageMarius IstrateNessuna valutazione finora

- Choox TVDocumento3 pagineChoox TVDon LabNessuna valutazione finora

- My ThesisDocumento35 pagineMy ThesisHoyga AflaamtaNessuna valutazione finora

- Articles For Lecture 2Documento44 pagineArticles For Lecture 2Katerina Alex SearleNessuna valutazione finora

- How Urban Planning Works Guide DevelopmentDocumento3 pagineHow Urban Planning Works Guide DevelopmentnavinNessuna valutazione finora

- Claudio Ferrari - University of Genova, ItalyDocumento19 pagineClaudio Ferrari - University of Genova, ItalykuselvNessuna valutazione finora

- Corporate Social Responsibility in Shipping CompaniesDocumento9 pagineCorporate Social Responsibility in Shipping CompanieshamadbakarNessuna valutazione finora

- Marine Policy: Paul FentonDocumento7 pagineMarine Policy: Paul FentonSudeepSMenasinakaiNessuna valutazione finora

- COVID-19 Impact on Public TransportDocumento6 pagineCOVID-19 Impact on Public TransportMela TumanganNessuna valutazione finora

- Perpel Lanjut (Refrensi)Documento32 paginePerpel Lanjut (Refrensi)Valerie Masita HariadiNessuna valutazione finora

- Urbact.eu Welcome Rotterdam – Mayor AboutalebDocumento8 pagineUrbact.eu Welcome Rotterdam – Mayor AboutalebAugusto CésarNessuna valutazione finora

- Module Title: Port Operations Port Performance Indicators. What Is Transportation?Documento71 pagineModule Title: Port Operations Port Performance Indicators. What Is Transportation?Victor Ose MosesNessuna valutazione finora

- Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in The Shippping Industry: A Distubing Mechanism Between Maritime Security Needs and Seafarers' Welfare.Documento13 pagineCorporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in The Shippping Industry: A Distubing Mechanism Between Maritime Security Needs and Seafarers' Welfare.hamadbakarNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction to Project Finance in Renewable Energy Infrastructure: Including Public-Private Investments and Non-Mature MarketsDa EverandIntroduction to Project Finance in Renewable Energy Infrastructure: Including Public-Private Investments and Non-Mature MarketsNessuna valutazione finora

- This Item Is The Archived Peer-Reviewed Author-Version ofDocumento24 pagineThis Item Is The Archived Peer-Reviewed Author-Version ofyrperdanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sustainability 10 01953Documento20 pagineSustainability 10 01953Leila TaminaNessuna valutazione finora

- Water Conference Full Report 0Documento32 pagineWater Conference Full Report 0rentingh100% (1)

- Sustainability 08 00922 v2 PDFDocumento31 pagineSustainability 08 00922 v2 PDFJabelle Mae DoteNessuna valutazione finora

- Bogers-Afuah-Bastian 2010 JOM Users As InnovatorsDocumento19 pagineBogers-Afuah-Bastian 2010 JOM Users As InnovatorsBiYa KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Dance Performance ReviewDocumento5 pagineDance Performance ReviewNabila ZulfiqarNessuna valutazione finora

- Liu 302Documento7 pagineLiu 302BiYa KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Role of HR in Resolving Conflict in The Organization PDFDocumento1 paginaThe Role of HR in Resolving Conflict in The Organization PDFBiYa KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Reflective Essay Booklet - CTL, University of NewcastleDocumento7 pagineReflective Essay Booklet - CTL, University of NewcastleBiYa KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Dance Performance ReviewDocumento5 pagineDance Performance ReviewNabila ZulfiqarNessuna valutazione finora

- The Role of HR in Resolving Conflict in The OrganizationDocumento1 paginaThe Role of HR in Resolving Conflict in The OrganizationBiYa KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Wetzel2018 Article BuildingAndLeveragingSportsBraDocumento22 pagineWetzel2018 Article BuildingAndLeveragingSportsBraBiYa KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- MLA Format and GuidelinesDocumento7 pagineMLA Format and GuidelinesBiYa KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Scavenger Hunt A Team Building ExerciseDocumento8 pagineThe Scavenger Hunt A Team Building ExerciseBiYa KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Computers: The Emergence of Internet of Things (Iot) : Connecting Anything, AnywhereDocumento4 pagineComputers: The Emergence of Internet of Things (Iot) : Connecting Anything, AnywhereBRAYAN STEAD RODRIGUEZ CRUZNessuna valutazione finora

- Colbert Et Al (2012) PDFDocumento16 pagineColbert Et Al (2012) PDFBiYa KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- McAdams (Donald Trump Personality) - 1Documento37 pagineMcAdams (Donald Trump Personality) - 1BiYa KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Pakistan Regional Pivot and The Endgame in AfghanistanDocumento20 paginePakistan Regional Pivot and The Endgame in AfghanistanJoey AliNessuna valutazione finora

- Alignment Quiz Reveals Character BeliefsDocumento7 pagineAlignment Quiz Reveals Character BeliefsDorian Gaines100% (1)

- The Economist UK Edition - November 19 2022-3Documento90 pagineThe Economist UK Edition - November 19 2022-3ycckNessuna valutazione finora

- Dr. B. R. Ambedkar's Role in Revival of BuddhismDocumento7 pagineDr. B. R. Ambedkar's Role in Revival of BuddhismAbhilash SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Gulliver's Travels to BrobdingnagDocumento8 pagineGulliver's Travels to BrobdingnagAshish JainNessuna valutazione finora

- C6 - Request For Citizenship by Marriage - v1.1 - FillableDocumento9 pagineC6 - Request For Citizenship by Marriage - v1.1 - Fillableleslie010Nessuna valutazione finora

- Imm5406e Final - PDF FamilyDocumento1 paginaImm5406e Final - PDF FamilyAngela KhodorkovskiNessuna valutazione finora

- Texas Farm Bureau Insurance Arbitration EndorsementDocumento2 pagineTexas Farm Bureau Insurance Arbitration EndorsementTexas WatchNessuna valutazione finora

- International and Regional Legal Framework for Protecting Displaced Women and GirlsDocumento32 pagineInternational and Regional Legal Framework for Protecting Displaced Women and Girlschanlwin2007Nessuna valutazione finora

- Latar Belakang MayzulDocumento3 pagineLatar Belakang MayzulZilong HeroNessuna valutazione finora

- KKDAT Form 1Documento2 pagineKKDAT Form 1brivashalimar12Nessuna valutazione finora

- Monday, May 05, 2014 EditionDocumento16 pagineMonday, May 05, 2014 EditionFrontPageAfricaNessuna valutazione finora

- History of Agrarian Reform and Friar Lands in the PhilippinesDocumento24 pagineHistory of Agrarian Reform and Friar Lands in the PhilippinesAngelica NavarroNessuna valutazione finora

- Ari The Conversations Series 1 Ambassador Zhong JianhuaDocumento16 pagineAri The Conversations Series 1 Ambassador Zhong Jianhuaapi-232523826Nessuna valutazione finora

- Mariano Jr. v. Comelec DigestDocumento3 pagineMariano Jr. v. Comelec DigestAnonymousNessuna valutazione finora