Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Federalism Final

Caricato da

SusilPandaDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Federalism Final

Caricato da

SusilPandaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

1

INTRODUCTION

Federalism is commonly identified with the theory of federal government.

According to this interpretation, put forward particularly by the Anglo-

Saxon school, federalism is specific form of government, a constitutional

model, with an historically determined juridical structure. There is therefore

an American federalism, a Swiss federalism, a German federalism, an

Australian federalism and so on. The definition of federal government by

Where is - according to this interpretation - the most accurate: In a federal

system, the functions of government are divided in such a way that the

relationship between the legislature which has authority over the whole

territory and those legislatures which have authority over parts of the

territory is not the relationship of superior to subordinates ... but it is the

relationship of co-ordinate partners in the governmental process.

A different interpretation of federalism has been put forward by the

`personalist' movement, which stresses the relevance of a `federalist' way of

thinking and acting. `Personalist' or `integral' federalists, such as Robert

Aron, Arnaud Dandieu, Alexandre Marc, Emmanuel Mounier, Daniel Rops,

Denis de Rougemont, and Henry Brugmans, have developed a global

conception of society with a metahistoric character, starting from the thought

of Proudhon.

A constitutionally guaranteed sharing of power between levels of

government. Some powers of decision are granted to provincial (sub-

national) government, while others remain the sole concern of the national

government. The degree of independence for provincial governments (and

2

conversely, the power of the national government) varies from country to

country. Citizens of a federal system remain subject to the authority of both

the central and the provincial governments, each of which acts directly on

the citizen.

Meaning & Definition

Federation : Federation is a "convention by which several petty states agree

to become members of a large one which they intend to establish."

According to Finder, "a Federal State is one in which part of the authority

and power is vested in the local areas while another part is vested in a central

institution deliberately constituted by an association of the local areas." In

the words of Dicey, "a federal State is a political contrivance intended to

reconcile national unity and power with the maintenance of 'state rights'.

The word federation is derived from the Latin word loedus' which means

treaty or agreement. A federation comes into existence when two or more

hitherto independent States agree to form a new State surrendering their

sovereignty to the latter, or when the administrative units in a unitary

government make the centre agree to bestow autonomy upon them. The

former of these processes is known as 'integration' and the latter as

'disintegration'. When some economically backward or militarily weak

States voluntarily agree to unite, they form a federal union. Such a union is

brought about through a treaty or an agreement. A new State is created, to

which all the mutually agreeing States surrender their sovereignty. The

United States is an example of such a type of federation.

3

THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF FEDERALISM

Federalism was carefully defined in the Constitution as a founding principle

of the U.S. political system. Even so, the nature of federalism is dynamic

and has been shaped through the years by laws, Supreme Court decisions,

and debates among prominent elected officials and statesmen.

Federalism As Provided In The Constitution

When the colonies declared their independence from Britain in 1776, they

reacted against the British unitary system in which all political and economic

power was concentrated in London. Although the British did not impose this

power consistently until after the French and Indian War ended in 1763, new

controls on the colonial governments during the 1760s became a major

source of friction that eventually led to war. During the American

Revolution, the states reacted to Britain's unitary system by creating the

Articles of Confederation that gave virtually all powers to the states. The

framers at the Constitutional Convention tried to balance the perceived

tyranny of the unitary system with the chaos created by the confederal

system by outlining a hybrid federal system in the Constitution. Federalism,

then, became a major building block for preserving freedoms while still

maintaining order in the new nation.

4

Characteristics of Federalism

Federalism has the following characteristics of its own and these

characteristics distinguish it from Unitarianism.

1. In a federal state there are two sets of governments, one is called

federal or central government, the other is provincial or Unit

governments. The union of these two sets of governments makes what

is called federation. Each government is independent of the other in its

own jurisdiction. The central and unit governments are

constitutionally equal in status and position :non s superior to other.

2. In a federation governmental powers are essentially distributed by the

constitution between the Central government on the one hand and the

unit government on the other. The details of division vary in different

federations. But the principle followed in the division is that all

matters which are primarily of common interest and require

uniformity of regulation throughout the country such as foreign

affairs, defense, currency and coinage are placed under the central

government, and the rest is left to the Unit governments.

3. Federal system essentially implies the supremacy of constitution. A

federal state derives its existence from the constitution; powers of

both central and unit governments are delegated by the constitution.

Every power whether of central or Unit governments is subordinate

to, and controlled by, the constitution. For instance, in the united

states neither the president nor the Congress nor the governor of New

York nor its legislature can legally exercise a single power which is

inconsistent with the articles of the constitution. Every legislature

existing under a federal constitution is merely a subordinate law-

5

making body, whose laws are valid while within authority conferred

on it by the constitution, invalid if they go beyond the limits of such

authority.

4. To maintain in practice the supremacy of the constitution every

federal state must have a supreme court. It interprets the constitution,

decides disputes between center and province or provinces, or

between different organs of government. It puts them in check, keeps

them within their constitutional limits.

5. The federal constitution being a complicated contract and the supreme

law of the land is essentially a written and rigid one.

6. In a federal state there exists some sort of double citizenship and

allegiance. This means that a citizen has to show allegiance both to

the provincial and federal governments,

7. The central legislature under federal system is generally found

bicameral on the age old ground that the lower house enshrines the

national idea and represents the nation as a whole and the upper house

is enshrine federal idea and to represent the units as such.

6

FEDERALISM IN INDIA

Federation is the existence of dual polity. There are two governments in

existence- e.g. Government of Federation (in India Union Government) and

Government of Unit (in India- State Government). These two sets of

Government do not subordinate with each other. They cooperate with each

other and are independent to each other. Indian Constitution resembles a

federal constitution but in essence it is not a federal constitution. The unique

feature of Indian constitution is the presence of features which are necessary

for existence of a federation, at the same time there are provisions which

make the Union Government powerful vis-a-vis that of State governments.

Hence Indian constitution can be termed as "Quasi- federal" in nature and

Indian Union can be called as "Centralized Federation". Former Chief

Justice Beg, in State of Rajasthan v UOI, 1977 called the Constitution of

India as 'amphibian'. He said that "...if then our Constitution creates a

Central Government which is 'amphibian', in the sense that it can move

either on the federal or on the unitary plane, according to the needs of the

situation and circumstances of a case...". Likewise in S.R. Bommai v Union

of India, the phrase "pragmatic federalism" was used. In the words of Justice

Ahmadi, "....It would thus seem that the Indian Constitution has, in it, not

only features of a pragmatic federalism which, while distributing legislative

powers and indicating the spheres of governmental powers of State and

Central Governments, is overlaid by strong unitary features..."

India has a constitutional and political system which has some federal

features. The Constitution provides the Central government with

overarching powers and concentrates administrative and financial powers in

7

its hands. At the same time, there is sharing of powers and resources

between the Central government and the states in a limited fashion. The

experience of partition at the time of independence conditioned the

Constitution makers to build in various features in the Constitution which

worked against the federal principle.

The Centre has the power to reorganise the states through Parliament;

Governors appointed by the Centre can withhold assent to legislation passed

by the state legislature; Parliament can override legislation passed by the

states in the national interests; the Governor can play a role in the formation

of state governments and the Centre is vested with the power to dismiss the

state governments under Article 356; residuary powers are vested with the

Centre and the major taxation powers lie with the Central authority.

Alongside these unitary features, there is a division of subjects between the

Centre and states and a concurrent list. Judicial review of Centre-state

relations exist as in a federal system. On the balance, the Indian political

system has federal features which are circumscribed with a built-in unitary

core.

8

The History of federalism in India

The history of federalism and Centre-state relations in India is marked by

political mobilisation and intermittent struggle to fashion a more federal set-

up. Even though such efforts have not yet resulted in any major

constitutional changes towards a more federal orientation, the struggle has

not been entirely fruitless. It will be useful to trace the tortuous course of the

movement for federalism. In the first phase lasting till the late sixties, the

task of nation building and development was the main concern of Indias

rulers. There were separatist problems in Jammu & Kashmir and Nagaland

in the North-East but these were seen more as challenges to national unity

and issues of national security. The drive towards centralisation which

began in this period also coincided with the period of Congress dominance

both the Centre and in the states.

But this period was not solely dominated by the trend of centralisation. One

of the major democratic movements in the post-independence period -- the

movement for the formation of the linguistic states -- took place in the fifties

which resulted in the formation of the linguistic states in 1956. The ruling

Congress and the Central government resisted this demand and gave in, in

the face of strong popular movements. This laid the basis for the later

assertion by the states for greater powers. The second phase began with the

1967 general elections. The Congress party, for the first time lost in nine

states and non-Congress state governments came into being, including the

Left-oriented United Front governments in West Bengal and Kerala. The

demand for restructuring of Centre-state relations picked up momentum.

The political response of the ruling party at the Centre under Mrs. Gandhis

9

leadership was to maneouvre to regain the lost political ground and pursue

policies designed to centralise more powers at the Centre both political and

economic.

The seventies and eighties, therefore, saw a tussle between the Congress on

the one hand and the regional and Left parties on the other for greater

powers to the states. Beginning with the Rajmannar Committee set-up by

the DMK government in 1969 to the memorandum on Centre-state relations

by the Left Front government of West Bengal in 1977 to the opposition

conclave on Centre-state relations in Srinagar in 1983 the framework for

the restructuring of Centre-state relations and a more federal political system

was prepared. The Central government responded by appointing the

Sarkaria Commission on Centre-state relations in 1983.

The drive for centralisation sought to undo the prospects of democratic

decentralisation effected by the formation of the linguistic states in 1956.

Resistance to decentralisation and more powers to states had its class

dimension. The Indian big bourgeoisie was hostile to any dilution of the

unitary character of the state. Their quest for a homogenous market led

them to condemn the demand for linguistic states as heralding the

balkanisation of India.

The political onslaught on federalism found expression in the repeated use

of Article 356 by the Central government to dismiss state governments, most

of whom were run by parties who were in the opposition. The Governor, in

the garb of the Constitutional post, became an agent for the Centre.

Progressive legislation passed by the states such as those concerning land

10

reforms by the West Bengal assembly were not given assent for years on

end. The division of financial resources between the Centre and the states,

instead of a Constitutional right, became a method to keep the states in a

supplicant and subordinate position. The Centre sought to transfer subjects

from the states list into the concurrent list whenever an opportunity

presented itself. Some of these actions reached their zenith during the

internal emergency when the 42

nd

Constitutional amendment was enacted.

The rigidity of the Constitutional political system with the Centre playing a

dominant and monopolistic role met with resistance. The rise of regional

parties, the DMK and the Akali Dal, were the earliest formations and the

subsequent proliferation of other regional parties had both an economic class

content and a cultural expression. The major linguistic-nationality groups

in India of which the most developed were the non-Hindi groups were

the first to throw up the regional parties. These regional parties expressed

the class interests of the rising bourgeois-landlord classes of that linguistic

group and they also tapped into the linguistic-cultural aspirations. In the

eighties, the rise of the Telugu Desam Party in Andhra Pradesh symbolised

this development.

The political contestation between the forces of centralisation and

federalism did not result in a clear-cut victory for either side. While there

has not been substantial changes in the unitary features of the Constitution

and the financial system, the political parties system has evolved on federal

lines. The end of Congress one-party dominance by the late eighties created

an atmosphere to check rampant centralisation.

11

For the first time, in 1989, a National Front coalition government headed by

V.P. Singh, which had major regional parties like the TDP, DMK and AGP,

took office at the Centre. Though short-lived, this government took certain

steps to strengthen the federal principle. The Inter-state Council was

constituted in 1990. The provision in the Constitution to set-up such a

council was not exercised by the Centre earlier. The entry of the regional

parties in coalition governments at the Centre became a regular feature in

1996 with the formation of the United Front government and in all

subsequent ones -- the 1998 and 1999 coalitions headed by the BJP and the

current United Progressive Alliance headed by the Congress coalition. Both

the National Front government of 1989 and the United Front governments of

1996-1998 were supported by the Left parties who are strong supporters of

the federal principle.

The participation of the regional parties in the Central coalition governments

has led to checks on the centralisation trend initiated by the Central

government. The political give and take within a coalition precludes the

possibility of a roughshod approach to states. Even the BJP which has no

sympathy for federal values proved adept at responding to the concerns of

the regional parties.

One of the obnoxious anti-federal features was the use of Article 356 by the

ruling party at the Centre. Halting the arbitrary use of this clause by

demanding its removal or modification has been the priority for all the

forces advocating a more equitable Centre-state relations. The Supreme

Court, by the Bommai judgement of 1994, made a significant contribution

towards restraining the Central government from misusing these powers.

12

The Court decreed that the exercise of the powers have been arbitrary and

militates against the federal principle. It provided for safeguards by

stipulating that a decision to dissolve the State legislature cannot be

implemented till both the Houses of Parliament approved the presidential

proclamation. Till then the dissolution should be kept in suspended

animation. The judgement also requires the President to set out the reasons

and the material on which basis the proclamation of Presidents rule is made.

The Court made this subject to judicial review. The judgement was

informed by the Constitutional perspective that federalism and democracy

are interconnected and one cannot be violated without harming the other.

Features of Indian federalism

Two sets of government: India has two sets of government - the Central or

Union government and the State government. The Central government

works for the whole country and the State governments look after the States.

The areas of activity of both the governments are different.

Division of Powers: The Constitution of India has divided powers

between the Central government and the state governments. The

Seventh Schedule of the Constitution contains three lists of subjects

which show how division of power is made between the two sets of

government. Both the governments have their separate powers and

responsibilities.

Written Constitution: The Constitution of India is written. Every

provision of the Constitution is clearly written down and has been

discussed in detail. It is regarded as one of the longest constitutions of

the world which has 395 Articles 22 Parts and 12 Schedules.

13

Supremacy of the Constitution: The Constitution is regarded as the

supreme law of the land. No law can be made which will go against

the authority of the Constitution. The Constitution is above all and all

citizens and organizations within the territory of India must be loyal to

the Constitution.

Supreme judiciary: The Supreme Court of India is the highest court

of justice in India. It has been given the responsibility of interpreting

the provisions of the Constitution. It is regarded as the guardian of the

Constitution.

Bi-cameral legislation : In India, the legislature is bi-cameral. The

Indian Parliament, i.e., the legislature has two houses - the Lok Sabha

and the Rajya Sabha. The Rajya is the upper house of the Parliament

representing the States while the Lok Sabha is the lower house

representing the people in general.

These are some of the features of a federal form of government and the

Indian Constitution has included them in it. The Constitution has also

included some unitary or non-federal features which are discussed as below:

Unitary or Non-Federal Features

Division of power is not equal : In a federation, power are divided equally

between the two governments. But in India, the Central government has

been given has been given more powers and made stronger than the State

governments.

14

Constitution is not strictly rigid : The Constitution of India can be

amended by the Indian Parliament very easily. On many subjects, the

Parliament does not need the approval of the State legislatures to

amend the Constitution. But in a true federation, both the Union and

the State legislatures take part in the amendment of the Constitution

with respect to all matters. Therefore, those constitutions are rigid and

difficult to amend.

Single Constitution: In India, we have only one Constitution. It is

applicable to both the Union as a whole and the Stares. There are no

separate constitutions for the States. In a true federation, there are

separate constitutions for the union and the States.

Centres control over States: The Centre exercises control over the

States. The States have to respect the laws made by the central

government and can not make any law on matters on which there is

already a central law. The centre can also give directions to the States

which they must carry out.

Rajya Sabha does not represent the States equality: In a true

federation, the upper house of the legislature has equal representation

from the constituting units or the States. But in our Rajya Sabha, the

States do not have equal representation. The populous States have

more representatives in the Rajya Sabha than the less populous States.

The upper house of the Indian Parliament, that is, the Rajya Sabha is

not properly representative of all the States of Indian union.

Existence of States depends on the Centre: In India, the existence of

a State or a federating unit depends upon the authority of the Centre.

The boundary of a State can be changed by created out of the existing

States.

15

Single citizenship: In a true federal state, citizens are given dual

citizenship. First, they are the citizens of their respective provinces or

States and then they are the citizens of the federation. In India

however, the citizens enjoy single citizenship, i.e., Indian citizenship

or citizenship of the country as a whole.

Unified judiciary: India has a unified or integrated judicial system.

The High Courts which work in the States are under the Supreme

Court of India. The Supreme Court is the highest court of justice in

the country and all other subordinate courts are under it.

Proclamation of emergency: The Constitution of India has given

emergency powers to the President. He can declare emergency in the

country under three conditions. When emergency is declared, the

Union or Central governments become all powerful and the State

governments come under the total control of it. The State

governments lose their autonomy. This is against the principles of a

federation.

16

RELATION BETWEEN STATES AND UNION

Generally, three models are followed in the matter of division of powers in a

federation. In the first model, the powers of the Centre are defined and the

residuary powers are left to the States. This model is found in America. In

the second module, the powers of the federating units or States are defined

and the residuary powers are given to the centre. Canada follows this model.

And in the third model, the powers of both the governments are clearly laid

down. Australia has this model of federation. In India, we follow the

combination of both the Canadian and the Australian models.

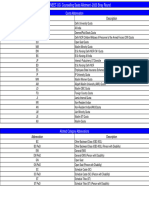

The Constitution of India divides powers between the Union and the State

governments. The Seventh Schedule of the Constitution includes three lists

of subjects - the Union List, the State List and the Concurrent List. The

Central or Union Government has exclusive power to make laws on the

subjects which are mentioned in the Union List. The States have the power

to make law on the subjects which are included in the Concurrent List. With

regard to the Concurrent List, both the Central and State governments can

make laws on the subjects mentioned in the Concurrent List. Finally, the

subjects which are not mentioned in the above three lists are called residuary

powers and the Union government can make laws on them.

It may be noted here that in making laws on the subjects of the Concurrent

list, the Central government has more authority than the State governments.

And on the subjects of the State List also the Central government has

indirect control. All this shows that though the Indian Constitution has

17

clearly divided powers between the two governments, yet the Central

government has been made stronger than the State governments.

We can discuss the division of powers between the two governments in

India under three headings, such as, legislative relations, administrative

relations and financial relations with reference to the three lists.

Legislative Relations

So far as the legislative relations between the Central government and the

State governments is concerned, the Central government has been given

exclusive power to make law on the subjects of the Union list. The union list

has 96 subjects. These subjects are of great importance for the country and

uniform in character. So, these subjects are given to the Union government.

Some such subjects are defence, foreign affairs, currency and coinage,

citizenship, census, etc.

The State governments can make laws on the subjects mentioned in the State

list. The State list has 61 subjects. The subjects which are of local

importance and may vary from State to State are included in the State list.

Some subjects of the State list are - law and order, public health, forests,

revenue, sanitation, etc. Though the State governments have power to make

laws on the subjects of the State list, yet the Central government, on certain

occasions, can also make laws on these subjects. For example, during the

period of emergency, the Parliament makes laws on State subjects.

The Concurrent list has 52 subjects. On these subjects both the central and

18

the state governments can make laws. The subjects which are of great

importance and uniform in character but man require local variations, are

included in the Concurrent list. In respect of Concurrent list also, though

both the governments can make laws on the subjects included in the list, yet

the laws made by the Central government will prevail over the State laws in

case of a conflict between the two. Some subjects of this list are economic

planning, social security, electricity, education, printing and news papers,

etc. In case of residuary powers, the Union government has exclusive power

to make laws. The States have nothing to do in this regard.

Thus, we find that in legislative matters, the Union Parliament is very

powerful. It has not only exclusive contral over the Union list and the

residuary powers, but it has also dominance over the Concurrent list and the

State list.

Administrative Relations

As in legislative maters, in administrative matters also, the Central

government has been made more powerful than the States. The Constitution

has made it clear that the State governments cannot go against the Central

government in administrative matters. The State governments have to work

under the supervision and control of the Central government. The States

should exercise its executive powers in accordance with the laws made by

the Parliament. The Central government can make laws for maintaining

good relations between the Centre and the States. It can control the State

governments by directing them to take necessary steps for proper running of

administration. If the State fails to work properly or according to the

19

Constitution, it can impose Presidents rule there under Article 356 and take

over its (the States) administration. Again, there are some officials of the

Central government, working in the States, through which it can have

control over the State governments.

Financial Relations

To run the administration properly, both the Central and the State

governments need adequate sources of income. The income of the

government comes mainly from various taxes imposed by it. In financial

relations between the two governments, we will discuss how the sources of

income are adjusted between the to governments.

There are certain taxes like land revenue, tax on agricultural income, estate

duty, etc., which are levied and collected by the States. They are the sources

of State revenue. Some taxes are there like stamp duty, excise on medicine,

toilet preparations, etc. which are levied by the Union but collected and

appropriated by the States. There are some other taxes also which are the

sources of income of the Union government alone. They are revenue earned

from railways, posts and telegraphs, wireless, broadcasting, etc.

In financial matters also, the central government is more powerful than the

States. The President of India has the power to make alterations in the

distribution of revenues earned from income-tax between the centre and the

States. The Centre has also the power to great loans and great-in-aid to the

State governments. The Comptroller and Auditor General India and the

Finance Commission of India which are the central agencies also have

control over the State finances.

20

Efforts For The Improvement Of Centre-State Relations

It should be noted that since independence till 1967, the Union government

exercised increasing powers over the States because of the rule of a single

party (Congress) over both the Centre and the States. The party discipline

and the role of national political leaders oversha-dowed the issue of State

autonomy. In 1967, non-Congress governments were formed in many States

which raised the issue of State autonomy and demanded more powers and

financial resources to the States. Inspite of opposition from the States, the

Union governments have been using various provisions of the Constitution

to increase their power and control over States. Some of the important

mechanisms of the Union government are given belowl

1. The Constitutional Amendments. more important are third, sixth,

seventh, forty.-second and fifty - ninth Constitutional amend-ments.

2. By invoking emergency provi-sions.

3. By imposing President's rule in the States. For example, the Pre-

sident's rule was imposed in Punjab for 2100 days from June 1951 to

April 1988.

4. By the appointment and func-tioning of the office of the Gov-ernor.

The Governors have created troubles for the State governments at the

behest of the ruling party at the Centre

5. By the arrangement of All India Services.

6. By the appointment and transfer of Judges of High Court/ Supreme

Court.

7. By exploiting the dependency of the States on the Union govern-ment.

8. By a centralised Election Machi-nery

9. By the control of the means of communications such as Radio and

Television.

21

CRITICAL ANALYSIS

Federalism and Inequality in India

The empowerment of Indias sub-national political actors rolls on with the

news that the Samajwadi Party are set to triumph in the elections of Uttar

Pradesh, a huge state in North-East India with a population of over 200

million people. Widely reported as being a state-of-the-nation litmus test for

public opinion towards the ruling coalition headed by the Congress Party,

the results indicate the continuation of emergent trends and, potentially, the

increased opposition to entrenched problems, within Indias politics.

Congress currently look likely to finish fourth in the polls, despite vigorous

campaigning from party darling Rahul Gandhi, whilst the incumbent

Mayawati, of the Dalit-oriented Bahujan Samaj Party, has failed to hold onto

control.

Post-Cold War transformation in India has seen a shift, in economic,

political, and social affairs, away from a heavily centralised model to a new,

equally choatic but more dispersed structure. This is not to say that the

monolithic Indian state of old no longer exists, but as economic policy has

empowered states to develop their own models, so political power has

drifted away from the centre, with concurrent impacts on social

mobilisation. Victory of the Samajwadi Party further institutionalises the

new reality of weakened national parties, coalition government, and the

empowerment of state-level actors and authority.

This is a process that has been ongoing for decades but the elections in Uttar

Pradesh (UP) bring three key areas into focus: the division of the electoral

dividend created by anti-corruption campaigning and sentiment, the

22

enduring validity of dynastic political control, and the aforementioned

impact of a redefined federalism. There is, of course, a fourth meta-point

that never disappears: the role of caste politics.

Whilst the high profile leader of last year's protests against governmental

corruption, Anna Hazare, has largely disappeared from the political scene,

the discontent on which he capitalised, and the lack of resolution to the

problems he broadly addressed, remains. Corruption is no stranger to Indian

politics but there is certainly an increasing dismay at the extent to which it

appears endemic and immovable. At a time when the political paralysis

caused by clientalism and rent-seeking behaviour poses grave danger for the

rising India vision that middle classes have bought into, the spluttering of

the growth engine exacerbates outrage at an increasingly dishevelled

establishment. With GDP forecasts reduced, and inflation rising, the ruling

United Progressive Alliance coalition headed by Congress needed to

dynamically demonstrate that it is in touch with an India in flux. Despite

this, in entrusting reinvigoration to the latest product of the Nehru-Gandhi

dynasty, Congress may have compounded its own crisis.

Rahul Gandhi is the latest in a long-line of politicians drawn from the

bloodline of Jawaharlal Nehru, Indias central founding father and first

Prime Minister. At 41 he is General-Secretary of the Congress Party and,

following in the footsteps of other prominent family members such as

former Prime Ministers Indira Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi, and current Congress

President Sonia Gandhi (widow of Rajiv), Rahul is the most high profile

face of a new generation of politicians within a party whose current leader,

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, is 79. During the UP elections he

campaigned vigorously, making over 200 appearances on the stump to

23

promote his partys message. Whilst honestly accepting responsibility for

the defeat is commendable, the reality of failure may indicate a wider loss of

legitimacy relating to one of the bones of contention highlighted by

Ramachandra Guha recently as emblamatic of stagnation within Indias

democracy the stifling of credible politicians at the hands of dynastic

elites.

With all this in mind, the reinvigoration of representative democracy within

India is likely to come from the local level (though obviously local is a bit

relative when UP is the size of Brazil). Mayawati, incumbent Chief Minister

since 2007, is a much-debated example of this possible trend. Rising to

power on the back of an electoral base in the Dalit (untouchable)

community, Mayawati has faced criticism for a huge rise in her personal

wealth since assuming office and also for constructing prominent statues of

herself and other members of the Bahujan Samaj Party throughout the state.

This fuzziness over corruption, while possibly not the central factor in her

failure to retain office, is certainly a weakness and may have played into the

Samajwadi Partys successful campaigning within Other Backward Caste

communities left out of the alleged patrimonial spoils.

The great success of India as a democracy has been the endurance of

pluralism amidst stupendous diversity. Devolution of political power is a

logical extension of this, even more so half a century out from independence

as the contemporaries of Gandhi and Nehru depart the scene. Nonetheless

the central institutions of the Indian state are essential, and they surely

demand strong mass parties capable of leading coalitions and responding

proactively to the needs of the majority of Indians who are yet to reap the

tangible benefits of recent resurgence. There is, arguably, an increasing

24

sense that simply trotting out the latest Nehruvian prince, however gifted, is

not sufficient to placate the demands of a majority who are hungry for their

piece of the much-heralded bigtime.

As regards Indias role in the world, the management of inequality is

completely central. Where India presents itself as the worlds largest free

market democracy it is hindered by enduring mass poverty, especially in a

political system where the voting poor cannot be sidelined. Equally, linked

to the Nehruvian foreign policy angle that presented India as a representative

of the global poor seeking to construct an equitable global order away from

post-colonial power politics, an argument that presents India as a potential

global swing state is undercut by attempting to speak morally

internationally without having solved the same problems domestically. India

is, very obviously, not China. Nor is it Russia. Defining its worldwide

identity as a democratic force for the global good means ensuring the

economic success story continues to lift people out of poverty. It means, in

short, backing up some old-school great power rhetoric with some

iconoclastic great power responsibility. That example, successfully

achieved, would be phenomenal.

It is not a gigantic step for an electorate appalled by public corruption to

zero in upon issues relating to wider economic inequality. The UK itself is

an example of this, where public outrage towards MPs expenses and cash for

questions has drawn a line whose precedent is undermined by turning a blind

eye to bank bailouts, big business tax avoidance, and the simultaneous

imposition of austerity policies. The solidification of such a position within

India could coalesce around a series of sub-national groups, linked to caste

status, that may force not only significant reform upon central parties such as

25

Congress or the Bharatiya Janata Party, but also challenge the accelerated

model of federalised liberalisation that has empowered and caught the

imagination of the new Indian middle classes. This faultline, between the

passengers and the baggage in the Indian transformation, will represent the

pivotal issue around which continued reform turns and Indias new global

role is defined.

26

THE RECOMMENDATIONS OF SARKARIA COMMISSION

:UNION-STATE RELATIONS:

For a review of whole gamut Centre-State relations, the Union Government

appointed the Sarkaria Commission in 1983. Justice R.S. Sarkaria (Retd.)

was made the Chairman and Mr. B Sivaraman, the Cabinet Secretary, Mr.

S.R. Sen, a former Executive Director of IBRD and Rama Subramaniam

(Member Secretary) were nominated as other members. The Sarkaria

Commission was to examine and review the working of the existing

arrangements between the Union and States in regard to powers, functions

and responsibility in all spheres and recommend such changes or other

measures as may be appropriate. Report of Sarkaria Commission. The

Sarkaria Commission thereafter examined the whole gamut of Centre-State

relations and prepared a report and submitted it to the Union Government in

October 1987. Some of the main recommendations of the Commission have

been as under :

1. Strong Centre should continue. The Sarkaria Commission has

favoured the retention of a Strong Centre. It has firmly rejected the

demand for the curtailment of the powers of the Centre in the interest

of national unity and integrity. "We absolutely need to have a strong

Centre and there is no doubt about it. Without that everything will

wither away." The Commission did not favour fundamental changes

in the provisions of the Constitution and asserted that the Constitution

had worked reasonably well and withstood the stresses and strains of

the heterogeneous society in the throes of change. However,

alongwith it, the report accepted the importance of preventing undue

centralism.

27

2. Rejection of demand for the Transfer of some subjects of the State

List to the Concurrent List. The Commission rejected the demand for

the transfer of certain State subjects to the Concurrent List. On the

other hand, it held that the Centre should consult the States on

concurrent subjects. The Commission also did not favour restrictions

on the powers of the Centre to deploy armed forces in the States, even

though it favoured consultations with the concerned State goverments

before these forces were actually deployed in the States.

3. Support for Cooperative Federalism. The Report favoured greater

cooperation between the Centre and the States. It wanted an end of

confrontation which had been a feature of Centre-State relations in

India for the last few years.

4. Recommendation regarding the Office of Governor. The Report

rejected the demand for the abolition of the office of the Governor. It

also rejected the suggestion regarding selection of Governors out of a

panel of names given by the States. It suggested that active politicians

should not be appointed as Governors. When a State and the Centre

were ruled by different parties, the Governor should not belong to the

ruling party at the Centre. Further, the Governor on retirement should

not be permitted to hold any office of profit.

5. Recommendation regarding the issue of Appointment of Chief

Minister. The report suggested that the leader of the majority party in

the legislature should be appointed as the Chief Minister. If no single

party enjoyed a clear-cut majority in the State Legislature, the person

who was likely to command a majority in the Assembly be appointed

Chief Minister by the Governor. In such a case, it should be obligatory

28

for the Chief Minster to seek a majority vote in the Assembly within

30 days.

6. Recommendation regarding summoning of the Sessions of the State

Legislature. Generally, the Governor should convene the session of

State Assembly only on the recommendations of the State Ministry,

but under certain circumstances he should have the right to use his

discretion in the matter oi summoning the session of the State

Legislature.

7. Changes in Financial Scheme. The Report did not agree with the

demand for major changes in the scheme of distribution of financial

resources as provided by the Constitution. However, it favoured

necessary modifications in the matter of sharing of corporate tax as

well as tax on advertisement and broadcasting.

8. Recommendation regarding Article 356. The Report turned down the

demand for doing away with Article 356 of the Constitution under

which President Rule could impose on a State on the grounds of

failure of constitutional government in the State. However, for

preventing its misuse by the Centre, the Report favoured that (i) it

should be sparingly used ; (ii) the reasons for the imposition of.

presidential rule in the State should be clearly stipulated in the

proclamation of emergency ; (iii) the State Legislative Assembly

should not be dissolved unless the proclamation has been approved by

the Parliament; and (iv) all possibilities of forming an alternative

government should be fully exhausted before imposing Emergency

under Artcle 356.

9. Three-language Formula favoured. The Report favoured the

implementation of the Three-language formula throughout the

29

country. It stressed special steps for activating the Linguistic

Minorities Commission.

10. Retention of All India Services. The Report rejected the demand for

the disbanding of All-India Services on the ground that it would

greatly undermine the unity and integrity of the country.

11. Autonomy of Mass Media. The Report favoured relaxation of

Central control over Radio and T.V. and wanted greater

decentralisation of authority in matters of their day-to-day operation.

It wanted the Radio and T.V. to strive for harmonious adjustments

between imperatives of national interest and aspirations of States. It

favoured use of simple Hindustani for broadcasts and use of common

words from other regional languages for evolving a uniform

vocabulary.

12. Miscellaneous Recommendations. The Report suggested several other

measures : (i) The Report recommended that judges should be

transferred only with their consent. (10 No Commission of Enquiry

against any Chief Minister of a State or a former minister of a State

Government should be appointed unless both the Houses of Union

Parliament make such a demand. (iii) No Inquiry Commission should

be appointed for holding an inquiry into the conduct of a Minister of

State in office, ur,less the proposal was approved by the Inter-

governmental Council. These have been the salient features of the

Report submitted by the Sarkaria Commission to the Union

Government. The Government of India has not yet taken any action

on the report. The non-Congress leaders, however, rejected this report

in the New Delhi meeting held in January 1988. The Regional parties

have also not accepted the recommendations made by this Report as it

30

fails to meet their demand for State Autonomy. Now the constitution

review commission has been examining the issue of the relations

between the union and states for suggesting certain desireable and

possible amendments designed for making these relations more

conducive for a healthier socio-economic development of the country

as a whole as well as for overcoming regional imbalances and

persisting under-development in several areas of the country. In this

era of Coalition Politics, in which regional parties and some state

parties have come to be power holders in the union government, it is

essential to check the new tendency towards regionalisation of

national decisions. There is every need to develop centre-state

relations in a cooperative-competitive mode. Neither the Union should

act as a commanding big brother dictating orders/policies to the states

nor tolerate the attempts of the states/regional parties at

regionalisation of national decisions.

31

CONCLUSION

The Constitution of India has described India as a Union of States and not

a federation. Dr. Ambedkar, the Chairman of the Drafting Committee of the

Indian Constitution, while explaining the meaning of the phrase, said that

though India was to be a federation, it was not the result of an agreement by

the States to join a federation which is why no state had the right to secede

from it. The federation is a union, because it is indestructible. He again said

that the States are sovereign in the field which is left to them by the

Constitution as the centre is in the field which is assigned to it.

So, though the Constitution makers made the Central government stronger

than the State governments, yet they wanted a cooperative federation. They

wished that States would perform their functions in their allotted spheres

freely and both the governments would co-operate rather than confront each

other.

But the real working of the Constitution in all these years shows that the

Centre has grown stronger day by day and that the States have become just

like administrative units of the Centre. They have not been able to work

freely and independently. The Centre has been changing the boundary of the

existing States from time to time in which the consent of the concerned

States was not regarded as necessary. Again, the Centre has also been using

Article 356 to have control over the States mostly in a discriminating way.

The role of the Planning Commission has also been contributing to the

strength of the Central government in financial matters. The Planning

Commission exercises control over the working of the State governments

and thus reduced the position of the States to the units of local

32

administration in a unitary system of government.But the States are always

resenting the stronger position of the centre and demanding autonomy so

that they can work independently in their own matters. The Rajamanner

committee, the West Bengal Government Memorandum on Union-State

Relations, the Anandpur Sahib Resolution and the J & K Assembly

Autonomy Resolution have all given a call for the grant of more powers to

the States. The Sarkaria Commission, in its report while accepting the need

for a strong Centre also favoured the devolution of more powers to the States

in some areas. The demand for State autonomy has become stronger with the

emergence of the regional political parties in different States and with their

growing influence in national politics.

In recent years, we have seen an important development in the working of

Indian federalism. No single national political party has been able to secure

absolute majority in the Parliament to form the government independently.

Various regional and local political parties have been emerging and playing

crucial role in the formation of coalition governments at the Centre. This

development to some extent has changed the face of Indian federalism.

However, India has been continuing with a strong Central government. But,

it is hoped that Coalition politics will enable Indian federalism to bring

about some positive changes in the Center-State relations, particularly, in the

use of Article 356 by the Central government, role of the Governor in a State

and the distribution of financial powers between the two governments. These

are some of the issues which have been constraining Centre-State relations

from the very beginning.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Claim Settlement of GICDocumento51 pagineClaim Settlement of GICSusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Telangana Movement Various Committes and Commissions Formed DuringDocumento7 pagineTelangana Movement Various Committes and Commissions Formed DuringSANTHAN KUMARNessuna valutazione finora

- RTI-Central Information CommissionerDocumento11 pagineRTI-Central Information Commissioneranoos04Nessuna valutazione finora

- Respondent - TC 9Documento29 pagineRespondent - TC 9aryan82% (11)

- This Is A Family GroupDocumento1 paginaThis Is A Family GroupSusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Claim Settlement of GICDocumento7 pagineClaim Settlement of GICSusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Consumer ProtectionDocumento8 pagineConsumer ProtectionSusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- 3rd Grand Get TogetherDocumento1 pagina3rd Grand Get TogetherSusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- DateDocumento1 paginaDateSusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- This Is A Family GroupDocumento1 paginaThis Is A Family GroupSusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- InvitationDocumento1 paginaInvitationSusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- EEG-1 and BEGE-101 Assignment (2018-19) Final ASGDocumento6 pagineEEG-1 and BEGE-101 Assignment (2018-19) Final ASGSapna SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Industrial DevelopmentDocumento55 pagineIndustrial DevelopmentSusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Making ProjectDocumento1 paginaMaking ProjectSusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- IndiaDocumento55 pagineIndiaSusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- 21 Healthier Trail Mix Recipes To Make YourselfDocumento12 pagine21 Healthier Trail Mix Recipes To Make YourselfSusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- ConclusionDocumento12 pagineConclusionSusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Industrialization and its Role in Indian EconomyDocumento71 pagineIndustrialization and its Role in Indian EconomySusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Industrialization and its Role in Indian EconomyDocumento71 pagineIndustrialization and its Role in Indian EconomySusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Types of GSTDocumento3 pagineTypes of GSTSusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Fact Sheet On Foreign Direct Investment (Fdi)Documento10 pagineFact Sheet On Foreign Direct Investment (Fdi)SusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Impact of Branding on Consumer Buying BehaviorDocumento8 pagineThe Impact of Branding on Consumer Buying BehaviorSusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- ChapterDocumento8 pagineChapterSusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Syed Farhan Hyder S. C. Acharya: Dissertation Paper 405 On The Study of Growth of HDFC LifeDocumento36 pagineSyed Farhan Hyder S. C. Acharya: Dissertation Paper 405 On The Study of Growth of HDFC LifeSusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Fact Sheet On Foreign Direct Investment (Fdi)Documento10 pagineFact Sheet On Foreign Direct Investment (Fdi)SusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- EditingDocumento61 pagineEditingSusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Study on Retail Banking Services of United Bank of IndiaDocumento23 pagineStudy on Retail Banking Services of United Bank of IndiaSusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Prepared by PC15MBA-034: Basanti BagDocumento23 paginePrepared by PC15MBA-034: Basanti BagSusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- ChapterDocumento8 pagineChapterSusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- ChapterDocumento8 pagineChapterSusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Indian FederalismDocumento10 pagineIndian FederalismSusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- One Important ThingDocumento13 pagineOne Important ThingSusilPandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Section-2: Status of Education Among Scheduled TribesDocumento32 pagineSection-2: Status of Education Among Scheduled Tribesbharat patelNessuna valutazione finora

- Aluminium Purja NBJDocumento2 pagineAluminium Purja NBJPuneet KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Municipal administration handoverDocumento1 paginaMunicipal administration handoverAnji SunkaraNessuna valutazione finora

- Letters From Tapan SenDocumento7 pagineLetters From Tapan SensmeaglegolumNessuna valutazione finora

- Letter To Atal Bihari VajpayeeDocumento1 paginaLetter To Atal Bihari VajpayeeNDTV100% (1)

- AC122Documento96 pagineAC122manojk172Nessuna valutazione finora

- No 47 - 96 97Documento167 pagineNo 47 - 96 97manish rajNessuna valutazione finora

- List of First in IndiaDocumento4 pagineList of First in IndiafaramohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- CJI - Head of Indian JudiciaryDocumento2 pagineCJI - Head of Indian JudiciaryChandan SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- Abbrevation DescriptionDocumento88 pagineAbbrevation DescriptionLakshmi ManasaNessuna valutazione finora

- Indian Coal Mines Dataset - January 2021-1Documento435 pagineIndian Coal Mines Dataset - January 2021-1Yash RaoNessuna valutazione finora

- High Court Judgment on Seniority of Deputationists Absorbed in Central Health ServicesDocumento39 pagineHigh Court Judgment on Seniority of Deputationists Absorbed in Central Health Servicesravindrarao_mNessuna valutazione finora

- President and GovernorDocumento13 paginePresident and GovernorVinay PanditNessuna valutazione finora

- Review of Modi GovernmentDocumento19 pagineReview of Modi GovernmentSubhrajyoti SarkarNessuna valutazione finora

- Madhya Pradesh Government building and land guidelinesDocumento138 pagineMadhya Pradesh Government building and land guidelinesrizwan ansariNessuna valutazione finora

- Ch.-2 Federalism: (A) Objective QuestionsDocumento5 pagineCh.-2 Federalism: (A) Objective QuestionsLucky SatyawaliNessuna valutazione finora

- Inviting Fresh Applications Under Mode 2 of Free Coaching Scheme For SC and OBC StudentsDocumento5 pagineInviting Fresh Applications Under Mode 2 of Free Coaching Scheme For SC and OBC StudentsRudra DhîráñåNessuna valutazione finora

- UP Police Directory 2012Documento76 pagineUP Police Directory 2012Ram Niranjan Tiwari50% (2)

- 52nd NDC Course 2012Documento8 pagine52nd NDC Course 2012hallohallo1Nessuna valutazione finora

- SBI PO ResultDocumento6 pagineSBI PO ResultgelcodoNessuna valutazione finora

- LOKPAL Aspirants LISTDocumento74 pagineLOKPAL Aspirants LISTQaiserNessuna valutazione finora

- SchemesTap - 1st To 30th April 2023 Lyst7865Documento83 pagineSchemesTap - 1st To 30th April 2023 Lyst7865eshwarNessuna valutazione finora

- Indian Political Science GK Book Indian Polity Book For SSC CGL Upsc RRB Exams - NodrmDocumento44 pagineIndian Political Science GK Book Indian Polity Book For SSC CGL Upsc RRB Exams - NodrmRakesh KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- CLAT Previous Year Papers 2008 2017 PDFDocumento262 pagineCLAT Previous Year Papers 2008 2017 PDFSatish BabuNessuna valutazione finora

- The Constitution of IndiaDocumento21 pagineThe Constitution of Indiamonali raiNessuna valutazione finora

- AG I (Depot)Documento2 pagineAG I (Depot)Deepak GBNessuna valutazione finora

- Supreme court judges list indiaDocumento1 paginaSupreme court judges list indiaKshitiz VaishNessuna valutazione finora