Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Literary Linguistics, Speech Moves

Caricato da

chgialopsosDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Literary Linguistics, Speech Moves

Caricato da

chgialopsosCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Manly Moves

in

A Raisin in the Sun:

A Discourse Analytical Assessment

by

Charis Gialopsos

A dissertation submitted to the

Department of English

of

The University of Birmingham

in part fulfilment of the degree of

Master of Arts

in

Literary Linguistics

Department of English

School of Humanities

The University of Birmingham

2000

Abstract

This dissertation examines the progress of Walter, the main character of

Lorraine Hansberrys A Raisin in the Sun, who is the plays dramatic focal

point, both structurally and thematically (Washington 1988: 111). Drawing on

analytical tools from discourse analysis (speech moves) and sociolinguistics

(politeness), I try to determine whether Walter achieves manhood. The analysis

is supported by findings from conversation analysis and by Grices Cooperative

Principle. After a brief discussion of the theoretical framework employed and

the play itself (chapter 1), I proceed with the analysis of four key selected

episodes from the play (chapters 2, 3, 4, 5), and present my findings in the final

part of the dissertation (chapter 6), where I argue that Walters case is more

complex than it might seem on a first encounter.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank my supervisor and tutor Professor Michael Toolan for all his

help and support. His suggestions and comments on this dissertation were

invaluable. Although Umberto Eco (1986) claims that it is bad taste to thank

your supervisor for doing his job, Michael did it in the best possible way and I

am grateful for this.

I also wish to thank Eleni Pappa for her critical reading of the draft. The eye of a

non-linguist is often more able to spot the unintelligible parts of a linguistic text,

than the eye of its writer.

Table of contents

Introduction 1

Chapter 1: Preliminaries 4

1.1 Speech moves 4

1.2 Politeness 6

1.3 The play 8

Chapter 2: Impoliteness and verbal abuse; You contented son-of-

a-bitch you happy? 10

Conclusion 17

Chapter 3: Indirectness and black-mail status; The New

Neighbours Orientation Committee 18

Conclusion 27

Chapter 4: Breaking and hearing bad news; Man, Willy is gone 29

Conclusion 35

Chapter 5: Self identity and inference; My father almost beat a

man to death 37

Chapter 6: Conclusion 46

Appendices

Appendix 1: Walter and George 51

Appendix 2: First meeting with Lindner 53

Appendix 3: Walter and Bobo 56

Appendix 4: Second meeting with Lindner 58

References 60

Introduction

1

Introduction

This dissertation is an attempt to understand some of the mechanics of

literary dialogue in the light of linguistics; in particular, how the characters of a

play are constructed and presented, in terms of discourse analysis. Therefore, a

more general title for the dissertation could be Stylistics and Discourse

analysis. Both topics have been subjected to many criticisms, one of the most

recent being Sinclair (2000), who spoke of an ad hoc character of literature

that is resistant to any analysis and who also warned that discourse analysis is

always fallible since you never know what will follow.

Nevertheless, despite such criticisms, there still are valid reasons for

doing both stylistics and discourse analysis. Stylistics can be viewed as a way

rather than a method a confessedly partial or oriented act of intervention, a

reading which is strategic, as all readings necessarily are (Toolan 1996: 124).

Since people do read literature each in their own way, some of them can try to

do it in a more strategic, analytical way. As for discourse analysis, its claimed

fault seems to be its virtue, at least in relation to stylistics. The fact that a

conversation can be unpredictable is what makes the analysis of it useful; while

for the discourse or conversational analyst an unpredictable or unclassifiable

move might cause the collapse of the theory, its existence is significant for the

stylistician.

In a way similar to Grices (1975) Cooperative Principle, where the

implicatures commence only when the maxims are flouted, the more important

discoursal messages often derive from cases foregrounded by the breaking of

the rules. That does not mean that stylistics can say nothing about a well-

formed conversation. The basic hypothesis governing discourse analysis in

Introduction

2

stylistics is that by observing patterns of speech act use we can begin to

understand the characters on stage and how they relate to one another (Short

1996: 195).

The play under examination is Lorraine Hansberrys A Raisin in the Sun,

considered by many an American classic. It ends with the following dialogue:

MAMA (quietly, woman to woman): He

1

finally come into his

manhood today, didnt he? Kind of like a rainbow after the

rain

RUTH (biting her lip lest her own pride explode in front of MAMA):

Yes, Lena.

The aim of the dissertation is to find what are the elements, if any, indicating in

terms of discourse analysis whether or not Walter reaches his manhood. In other

words the following question is posed: Is the observation that Walter has come

into his manhood justified in terms of the conversational behaviour he exhibits?

However, Walters behaviour is not the only issue examined, albeit the most

important. Someones status in a conversation, either a real person or a

character, is not determined only by his/her conversational behaviour, but in

addition by the way others interact with him/her as well. Hence, an additional

question examined is How do the people surrounding Walter speak to him?.

With this aim, two main frameworks are used, presented in the following

sections; the speech moves model found in Toolan (2000) and the politeness

model found in Brown and Levinson (1987). Both are employed with the

support of findings from other theories as well, e.g., conversation analysis and

sociolinguistic work on terms of address. Therefore, it can be said that the

dissertation has a further secondary, but more ambitious aim. Apart from

examining how and if Walter achieves manhood, it is an attempt to integrate

1

He refers to Walter, Mamas son and Ruths husband. More information on the characters

and the play is given in the section entitled The play p.8.

Introduction

3

domains of knowledge in linguistics that are interrelated, having shared

interests, but are rarely found together in extant stylistic analyses.

Chapter 1: Preliminaries

4

Chapter 1: Preliminaries

1.1 Speech moves

Before presenting the framework of speech moves employed,

clarification of the term move seems needed. Traditional speech act theory

(Austin 1962, Searle 1965, 1969 and others) was concerned with the act.

Sinclair and Coulthard (1975: 26) used the term move as part of their rank-

scale model and proposed five kinds of moves, namely, framing, focusing,

opening, answering, and follow-up. Burton elaborated the model increasing

the number to seven; framing, focusing, opening, supporting,

challenging, bound-opening and re-opening (Burton 1980: 61), while Tsui,

also drawing from the Birmingham tradition, reduces the number to four:

initiating, responding, follow-up 1, follow-up 2 (Tsui 1994: 61). All three

models have in common the structural conception of the move. Toolan,

interested in the tracing of functional categories, uses move this way,

commenting on its relation with the term act, thus:

Because the interest here is in the functional analysis of utterances

in goal-attentive talk, it has seemed more appropriate to use the term

speech move (with its connotations of intervention and

contribution to an ongoing and developing exchange) rather than

speech act, a term of art in an established tradition (Toolan 2000:

178).

The theory is based on Hallidays (1994: 68) remark that when people

are engaged in talk they give or demand a commodity, which is either goods-

and-services or information. The combination of the above parameters leads to a

scheme of four core conversational moves (Toolan 2000: 179):

Goods and services Information

Giving

Seeking

Undertaking

Request

Inform

Question

Chapter 1: Preliminaries

5

It must be noted that although the parameters are clear and well

established this is not also the case for the moves proposed. There are many

occasions during the analysis, where the classification of a move is problematic

and remains such, even after the attempt at classifying it. This is rarely due to

the existence of indirect speech acts

2

, such as I would like you to go now

(discussed in Searle 1975: 65) which the present theory treats as a Request.

Leech (1983: 178) points out that when one does observe them, illocutions

are distinguished by continuous rather than by discrete characteristics. It is

therefore difficult to have a watertight taxonomy that can strictly classify all the

instances of communication and interaction; this would result to the existence of

moves that are not totally compatible with the categories proposed.

For that reason the scheme can be considered as a continuum, in which

four fundamental types of move exist, but each move may merge with the other,

in certain cases. When this happens, an intermediate move is met, something

quite frequent in the analysis that proceeds.

These ambiguous moves are examined to a greater extent than the

others, for the following reason; since all moves amount to the identification of

moments in the drama where characters interact affected by their goals, feelings,

different constraints and other factors, it is important, if not to reach a final and

definite classification of each move, at least to attempt to understand its

dynamics and the way it relates to the context. Each complex move signals the

realisation of a specific choice from the many offered by what Halliday (1970a:

142) calls the meaning potential of language.

2

Regarding indirect speech acts it is useful to keep in mind Goods comment that the

illocutionary forces of many are so transparent that to call them indirect seems perverse

(quoted in Geis 1995: 132).

Chapter 1: Preliminaries

6

A fifth move, of secondary nature, is also part of the framework, that of

Acknowledgements. Acknowledgements are secondary because they are

semantically attenuated in that they are contingent upon some prior,

exchange-driving act (Toolan 2000: 183). For this reason and as the

dissertation examines the progress of a character through the play, that is his

active and not passive interaction, Acknowledgements are only briefly

commented upon.

1.2 Politeness

Brown and Levinson build their model, originally published in 1978, on

the concept of face, taken from Goffman (1967). They suggest that all

competent adult members of a society have face, the public self-image that

every member wants to claim for himself and recognise two aspects of face;

negative face: the want of every competent adult member that his

actions be unimpeded by others.

positive face: the want of every member that his wants be desirable

to at least some others (Brown and Levinson 1987: 61-2).

Stating that there are certain kinds of act that intrinsically threaten face,

what will be referred to as face-threatening acts (FTAs), Brown and Levinson

present four ways of doing an FTA, provided that one chooses to proceed in

doing it the fifth option out being not to go on with the FTA at all.:

i. without redressive action, baldly

on record ii. positive politeness

Do the FTA with redressive action

iv. off record iii. negative politeness

(adapted from Brown and Levinson 1987: 69)

In cases ii and iii the speaker shows his/her willingness to respect at least some

other element of the face of the hearer, despite his/her choice to do an FTA. In

Chapter 1: Preliminaries

7

the fourth case, the FTA is formulated in such a way that inferences must be

made by the hearer, in order to perceive the meaning of the act. Parameters that

determine the gravity of the FTA are the social distance of the two

participants, their relative power and the absolute ranking of impositions in

the particular culture (ibid.: 74).

Leech (1983: 132ff.) also discusses politeness, but in terms of a

Politeness Principle with six maxims, those of tact, generosity,

approbation, modesty, agreement and sympathy that function in a way

similar and complementary to Grices Cooperative Principle. Yet, as Fraser

(1990: 234) notes,

It is one thing to adopt Grices intuitively appealing Cooperative

Principle. It is quite another to posit a host of maxims involving tact,

modesty, agreement, appropriation, generosity, and the like, which

are claimed to be guidelines for polite interaction, but without either

definition and/or suggestions by which one could, on a given

instance, determine the relative proportions of influence from these

maxims.

Although this model has been applied to the analysis of literary discourse

(Leech 1992), the Brown and Levinson model is preferred, because of the

codification it allows, bringing forward mainly two hyper-strategies of

politeness, the positive and the negative.

One thing must be stressed regarding the discussion of politeness that

follows. Politeness is examined in its pragmatic and not its sociolinguistic

dimension. As Thomas (1995: 146) notes,

In speaking of politeness we are talking of what is said and not of

the genuine underlying motivation which leads the speaker to make

those linguistic choices.

That means that the instances of politeness met are not analysed for the sake of

the analysis and the mapping of the politeness strategies employed. Rather, they

Chapter 1: Preliminaries

8

are examined as strategic choices in the interaction, assumed to have been made

with the aim of allowing each participant to fulfil his/her own conversational

goals.

1.3 The play

A Raisin in the Sun is Loraine Hansberrys first play, originally

performed in 1959. The author is still spoken of with passion and reverence by

a younger generation of writers and critics whom she encouraged and

influenced (Washington 1988: 109), although she has left only a few marks of

her talent because of her early death in the age of 34. As Abramson (1967: 241)

notes, A Raisin in the Sun is the first play by a Negro of which one is tempted

to say Everyone knows it. Even those critics that doubt its literary value, like

Cruse who characterised it as the most cleverly written piece of glorified soap

opera (Cruse 1967: 278), concede its broad impression on the audience.

The play evolves around a family of African-Americans called the

Youngers, living in Chicagos Southside during the 1940s or the 1950s. The

members of the family are Mama, her two children Walter Lee and Beneatha,

Walters wife Ruth and their son Travis. The Youngers are a family of three

generations, with Mama at its head. Other characters involved, that will be met

in the analysis of the selected episodes, are George Murchinson, Karl Lindner

and Bobo.

The basic story-line that the play follows is built upon the inheritance of

ten thousand dollars, the insurance money given to the family for the death of

the father. Walter wishes to invest the money in a liquor store, while Mama

wants to buy a new house. As a compromise, Mama makes a downpayment for

Chapter 1: Preliminaries

9

the new house and gives the rest of the money to Walter in order to make his

investment and save some for the future studies of his sister. Nevertheless,

instead of following her directions Walter invests and loses all the money. As a

result, he at first decides to sell the new house at a higher price to the committee

of the white neighbourhood where the house is located, an offer which the

family had previously rejected. The play ends with Walter finally turning down

once more that offer and making peace with his family, who had disagreed with

selling the house.

The episodes that are examined have Walter, the focus of this

dissertation, as a main participant, observed in four different psychological

states and situations in the play:

- Episode 1: a casual conversation with George Murchinson (see

3

Appendix 1).

- Episode 2: the first meeting with Karl Lindner, while the family still

have the money (see Appendix 2).

- Episode 3: the announcement of the bad news the loss of the

money by Bobo (see Appendix 3).

- Episode 4: the second meeting with Karl Lindner, after all the money

has been lost (see Appendix 4).

3

The reader is advised to refer to the relevant Appendix before reading each chapter.

Chapter 2: Impoliteness and verbal abuse

10

Chapter 2: Impoliteness and verbal abuse; You contented

son-of-a-bitch you happy?

The first part examined (please see Appendix 1) is the first encounter of

Walter with George Murchinson, a member of a wealthy black family. In the

previous moments Walter was standing drunk on the table, addressing an

imaginary African tribe with a background of African music and applause from

Beneatha, dressed in Nigerian robes. George has come to their house to take

Beneatha to the theatre. After a brief yet intense argument between George and

her regarding her clothes, she decides to change them and George is left waiting

for her, having small talk with Walters wife Ruth. At this moment, and while

they are talking about New York, Walter re-enters to the scene.

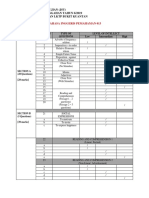

The table presents the primary speech moves that each of the

participants makes.

Table 1

Informs Questions Requests Undertakings Total

Walter

George

Ruth

39

3

3

21

1

0

3

0

6

1

1

0

64

5

9

78

The great number of moves made by Walter is evident. Out of 78 moves

64 are made by him, with only 14 left for both the other two participants. Walter

therefore occupies more than the 80% of the conversational time. Of course, the

number of the moves, by itself, can be a misleading clue, if the number of the

words each move is consisted of is not examined; still it shows, at least, the

tendency that a speaker has to engage in conversation. Only once does Walter

make a second-turn move in respect to George, as in just one of his moves is

Walter responding to an exchange initial move by George. This happens in their

Chapter 2: Impoliteness and verbal abuse

11

first verbal interaction in this part, where he is the third party that enters an

ongoing conversation. His previous initiating move, several lines earlier, was a

completely failed one, followed by a move that signified the end of that scene.

WALTER (to GEORGE, extending his hand for the fraternal

clasp): BLACK BROTHER !

GEORGE: Black brother, hell!

Lighting back to normal.

In line 7 Walter offers the Inform plenty of times that is prospected by

the question but it is one that clearly breaks the Quality maxim (Grice 1975:

46), as shown by the description of Ruth as shocked at the lie. He opts to

answer giving false information, in an attempt to save his face towards a rich

boy who has really been to New York plenty of times. This decision is

manifested by the fact that he repeats the Inform, at least the most important

part plenty, again after Ruths move.

One third of Walters moves are made in only two turn-takings (l.28-39,

47-52). Sacks et al., attempting to pinpoint the rules governing the turn-taking

say that transition from one speaker to another can proceed in two ways: either

the current speaker selects/nominates the next one, or the next speaker may self-

select and start talking in a transition-relevance place, where a move has been

completed. If nomination and self-selection are not employed, then the current

speaker may continue until the next transition-relevance place, the next

complete move (Sacks et al 1974: 703-4).

In both cases from the play, Walter offers more than one chance to

George to take the floor either by selecting him (l.28-9: Hows your old man

making out?; l.29: I understand you all going to buy that big hotel on the

bridge?; l.48: What the hell you learning over there?), or making his

contributions short, thus creating many transition-relevance places for someone

Chapter 2: Impoliteness and verbal abuse

12

willing to take the floor (l.31: Your old man is all right, man). Occasionally he

also pauses, as shown by the playwrights directions (l.23: a pause; l.29-31: he

finds a beer the other man). Nevertheless George does not take the floor until

it is totally abandoned by Walter (lines 40 and 53).

Yet, usually most of Walters moves are left hanging, not succeeded by

the move they prospect. His question in line 17 is unanswered; in fact George

withdraws from the conversation and he stays that way even after Ruths

Request (l.21: you have to excuse him), with Walter taking his turn. Again in

line 43, instead of George, we see Ruth reacting to his Inform. George violates

the Quantity maxim (Grice 1975: 45) by not giving the amount of information

expected; he does not give any information whatsoever.

The failure of Walters conversational attempts is also suggested by his

choices of certain moves and politeness strategies towards George. In line 34 his

utterance Id like to talk to him is ambivalent between Inform and Request,

without being what is traditionally called an indirect request of the sort of

can/could you pass the salt? (Searle 1975: 65). Although Searle (1975: 65) has

other examples in the form of I would like, he refers to the speakers wish

or want that H will do A, something absent from our case. Furthermore, other

constructions such as

Id like to win the lottery

clearly do not expect someone to do something about it and, therefore, cannot

be considered as Requests.

Walter informs George about his want to talk (probably business) to

his father. The character of the move, though, depends upon the participants

knowledge and beliefs. If Walter knows that George can bring him in touch with

Chapter 2: Impoliteness and verbal abuse

13

his father for this kind of talk, then he is making a Request. If George knows

that he can play this mediatory role, or that Walter is asking him to, then again it

is a Request, giving George the chance to recognise it as such and offer his help.

Yet, if none of the above is true, then the move is an Inform.

This is a case of an off-record FTA, since it is not possible to attribute

only one clear communicative intention to the act (Brown and Levinson 1987:

211). If challenged, Walter can always claim that it was an Inform and not a

Request. The fact that George does not reply to it, shows that he has also opted

to treat it as one more Inform among the others. When Walter sees his lack of

reaction, he proceeds in phrasing a clear Request me and you ought to sit down

and talk sometimes, man in line 39. He does so by redressive action, employing

both positive and negative politeness strategies.

Using the familiar address form man and referring to an implicit

inclusive we with me and you, he is claiming common ground between him

and George (Brown and Levinson 1987: 103). At the same time, by the use of

the more modalised yet deontic

4

ought, than the use of must for example,

and the indefiniteness of sometimes he tries to lesser the amount of imposition

on Georges face (Brown and Levinson 1987: 176ff) attending the latters

negative face. The Request that finally succeeds in becoming acknowledged is

also presented in a context where positive politeness has been used to a great

extent; notice the repeated use of I mean, you know and you dig. Brown

and Levinson discuss you know as a realisation of a positive politeness

strategy, aiming to assert common ground by the Personal-centre switch: This

is where S speaks as if H were S, or Hs knowledge were equal to Ss

4

The dilemma whether the modality is deontic or boulomaic is solved by the presence of

deontic modality in Georges rephrased well have to (l.40).

Chapter 2: Impoliteness and verbal abuse

14

knowledge (Brown and Levinson 1987: 119). I mean also flatters the positive

face of the hearer, probably signifying the following If I was as articulate as

you, I would say, or what I am trying to say, which I know you understand

because you are intelligent, is.

Nevertheless, his strategies do not seem to be able to overcome the lack

of interest that George has exhibited towards Walter and the conversation.

Georges second move in line 40 is another interesting case of violation of the

Cooperative Principle:

GEORGE (with boredom): Yeah sometimes well have to do that,

Walter.

By repeating Walters request he actually makes his contribution less

informative than required, flouting the Quantity maxim, as a means of

communicating his indifference. Furthermore, the use by George of the non

standard sometimes that Walter has previously used, George being a speaker

of the standard variety, can be regarded as ironic. As Sperber and Wilson note,

Irony is a variety of echoic utterance, used to express the

speakers attitude to the opinion echoed (Sperber and Wilson 1996:

265).

As Walter passes from a more polite off-record Request to a less polite

on-record one, similarly diminishes his general use of politeness towards

George. In lines 9-11 he tries to please him, by requesting Ruth to serve him

something, and jokes about the lack of entertainment. In line 17 he makes a

remark about Georges shoes, but attributing that type of shoes to all college

students, therefore making it sound less a personal insult. In line 42 he calls him

a busy little boy, and returns to the subject of the faggoty-looking shoes in

line 52. The final stroke, after Georges first openly challenging move in line

53, is to call him a son of a bitch in line 57.

Chapter 2: Impoliteness and verbal abuse

15

While Walters impoliteness towards George increases, Ruths address

of her husband changes relatedly. There are four moves that pose problems in

their classification and, thus, the understanding of the scene. These are the

following:

a) Walter Lee Younger! (l.8)

b) Walter Lee! (l.18)

c) Oh, Walter (l.27)

d) Oh, Walter Lee (l.46)

Each of them follows a move made by Walter, which was either a lie (as

in line 7) or an FTA aimed at George or Beneatha. But what is their function in

terms of the four moves designated as the descriptive apparatus? The existence

of oh in c and d indicates that they may be Acknowledgements. Since these

two are characterised as such and follow Informs, a which also follows an

Inform, can be considered an Acknowledgement as well. Finally b, having

roughly the same form as d, without the oh, could also be an

Acknowledgement. Still such a characterisation of these moves is problematic.

Firstly, b follows a Question, a move normally prospecting an Inform and not an

Acknowledgement, e.g.:

A How are you?

B1 Fine, and you?

*B2 Oh, thank you.

Secondly, these moves are not coming from George, the person that is addressed

by Walter, but from Ruth, who may bid for the floor.

I believe that another move made by Ruth in the same context

(following an Inform directed from Walter to George) can clarify the situation:

RUTH: Walter, please (l.43)

Chapter 2: Impoliteness and verbal abuse

16

Please is the word clearly denoting that a Request is made: its essential

function [please] is to get someone else to do something It can co-occur only

with a sentence which is interpretable as a request (Stubbs 1983: 72). Ruth is

trying to calm Walter and deter him from offending George, so it seems safe to

assume that the previous four moves had the same aim. Brown and Ford (1964:

241) describe the use of the complete name, case a, thus:

The use of the complete name [John Jones or even John

Montgomery Jones] is used as an intensifier and is particularly

favoured by mothers manding disobedient children (italics mine).

Therefore a is also a clear instance of Ruth, albeit not his mother, trying to

control Walters behaviour; she tries to stop him, therefore makes a Request.

Burton (1980) as well, although she characterises acts like a and b as

nominations recognises the fact that in unruly classes the use of a childs

name, spoken with, say, tone 4 (Halliday, 1970[b]) could well be used and heard

as a warning to stop behaving in ways that violate spoken and unspoken rules of

classroom behaviour (Burton 1980: 135n). Although this scene does not unfold

in a classroom, there are unspoken rules in a social encounter, such as the

respect of the others face, rules that Walter clearly breaks like a disobedient

pupil.

Finally, the employment of oh in c and d is another tool towards the

same aim, with Ruth using it in order to get Walters attention.

Oh marks a focus of speakers attention which then also becomes a

candidate for hearers attention Oh displays still another aspect of

participation frameworks: speaker/hearer alignment toward each

other Individuals evaluate each others orientations: what one

defines as appropriate level of commitment to a proposition, another

may define as inappropriate (Schiffrin 1987: 99-100).

Hence Ruth, watching Walter becoming more aggressive towards George and

seeing her efforts to control him fail, moves through a continuum of Requests

Chapter 2: Impoliteness and verbal abuse

17

ranging from the initial strict Walter Lee Younger to the final desperate Oh,

Walter Lee.

Conclusion

Walters main characteristic in this scene is the aggression he exhibits.

Firstly, and most notably, he is aggressive towards George. From their first

exchange he tries to challenge things related to him; his big life, connected to

New York, his appearance (his shoes), his education, George himself (son-of-a-

bitch). This hostility is not confined only to George, since neither Beneatha nor

Ruth escape his FTAs. Yet, more accurately, his moves should not even be

characterised as conventional FTAs that may threaten some aspect of the

hearers face in the course of an interaction. They aim to insult, formed as

Informs designed to be abnormally threatening to the hearers face (Toolan

2000: 184).

It was noted that the way Ruth interacts with Walter is typical of the

ways adults try to control the children. In addition, Walters behaviour is even

closer to a childs because of the underlying motives of his impoliteness. He

tries to harm Georges face because his own is harmed by Georges existence.

Walter is struggling to find a way of living a better life, a life that George takes

for granted. Therefore, his hostility derives from his envy towards George.

This motivates Ruth to attempt controlling him, or at least, to

communicate to George her desire of saving some of the familys face, by

indicating her efforts of doing so, and be civilised, through her Requests that

progressively faint facing Walters stubbornness.

Chapter 3: Indirectness and black-mail status

18

Chapter 3: Indirectness and black-mail status; The New

Neighbours Orientation Committee

The episode under examination (please see Appendix 2) commences a

few lines after the beginning of the third scene of act two. It is the moving day

for the Youngers and Beneatha and Ruth are preparing the packages. They are

in a very good mood, teasing each other, and Walter also participates in this

joyful atmosphere, when he enters the scene. For the first time in the play, these

three members of the Younger family are shown to get along peacefully with

each other. At this point the bell rings to introduce Karl Lindner the one white

character in the play, and along with him the crucial scene in Act II

(Abramson 1967: 249). He has come to bribe the family in order to keep them

out of his white neighbourhood (Washington 1988: 114).

These are the primary speech moves made by each participant:

Table 2

Informs Questions Requests Undertakings Total

Lindner

Walter

Beneatha

Ruth

39

5

7

2

0

7

3

0

7

8

2

0

0

1

0

2

46

21

12

4

82

It is not remarkable to see that Lindner is making half of the

conversational moves. Coulthard (1985: 80) notes the idea of reason for a call

or visit a basic assumption of all except chance encounters that the person

who initiated the encounter has some reason for so doing. Since Lindner is the

one paying them a visit, because of a specific reason, he is expected to hold the

floor for the extent of time that will allow him to display this reason. Walter is

Chapter 3: Indirectness and black-mail status

19

the next main speaker occupying 25% of the turn takings with Ruth being the

least actively participating character.

Walter takes his first two turns in the opening phase of the encounter.

Lindner has just come into the house and the participants are in the progress of

phatic communion whose function is

The detailed management of interpersonal relationships during the

psychologically crucial margins of interaction [and mainly] the

communication of indexical facts about the speakers identities,

attributes and attitudes [facilitating the interactants] to define and

construct an appropriate role for themselves in the rest of the

interaction (Laver 1975: 217-219).

The scene is the following:

WALTER (freely, the Man of the House): Have a seat. Im Mrs

Youngers son. I look after most of her business matters. Req/

Inf/ Inf

RUTH and BENEATHA exchange amused glances

MAN (regarding WALTER, and sitting): Well My name is Karl

Lindner

WALTER (stretching out his hand): Walter Younger. This is my

wife (RUTH nods politely.) and my sister. Inf/ Inf

We can therefore discern in Walters moves the identity and role that he

wishes to ascribe to himself. His first move is a Request done baldly, on-record.

This is justified since the request is actually in the interest of Lindner and the

amount of imposition is minimal (Brown and Levinson 1987: 69), but it may

also be strategically used to re-rank the social distance and the power between

the two men. They are strangers and of different race, yet the directness of

Walter claims intimacy and equality. He goes on to assert his status as the Man

of the House by introducing the other members of the family, after having

declared that he is the one responsible for handling his mothers business

matters. This projected self-image seems to be congruent with the greater

Chapter 3: Indirectness and black-mail status

20

number of moves he is making in comparison to the other members of his

family.

Yet the scene does not totally confirm this, as Beneathas contributions,

although fewer than Walters, seem to dominate the first half of the

conversation. To comprehend this feature it is necessary to consider Goffmans

discussion of some of the listeners in a talk:

[there are] those who overhear, whether or not their unratified

participation is inadvertent

5

and whether or not it has been

encouraged

6

; those (in the case of more than two-person talk) who

are ratified participants but are not specifically addressed by the

speaker; and those ratified participants who are addressed, that is,

oriented to by the speaker in a manner to suggest that his words are

particularly for them, and that some answer is therefore anticipated

from them, more so than from the other ratified participants

(Goffman 1981a: 9-10 italics mine).

Walter, then, in his behaviour in this opening phase, tries to justify himself as

the participant that must be addressed, something to which Lindner seems to

agree (eg: LINDNER: returning the main force to WALTER l.36), casting the

others as the unaddressed ones (Goffman 1981b: 133).

Nevertheless, Beneatha contests this, responding, before Walter does,

either with a Question or a meaningful Acknowledgement:

- Yes and what do they do? (l.35)

- Un huh. (l.40)

- Yes and what are some of those? (l.43)

- Yes. (l.50)

In the last two cases Walter tries to impose on her and regain his status as the

addressed participant with his Requests:

- Girl, let the man talk. (l.44)

5

An action labelled as overhearing in Goffman (1981b: 132).

6

An action labelled as eavesdropping in Goffman (1981b: 132).

Chapter 3: Indirectness and black-mail status

21

- Be still now! (l.51)

He succeeds in doing so in line 78 when he is the first to pose a Question

seeking clarification (What do you mean?). From then on Walter is the one

clearly confronting Lindner, with Beneatha making two more moves (l.90, 98)

that are connected but not clearly embodied in the conversation, as they are

Informs not prospecting a second-part move.

In the previous chapter Walters attempts to pass the floor to George

were discussed, and it was suggested that he was trying to do so by creating

many transition-relevance places in which George could take up the speech

(p.11-2). By contrast, the conversational behaviour of Lindner, this scenes main

character, is the exact opposite. Trying to hold the floor in order to explain the

thing in his own way (l.45-6) Lindner employs sentential constructions that

Sacks et al (1974: 709) regard as the most interesting of the unit-types, because

of the internally generated expansions of length they allow and, in particular,

allow before first possible completion places. He therefore usually produces

lengthy moves, such as the following:

LINDNER: It is one of these community organisations set up to

look after oh, you know, things like block upkeep and special

projects and we also have what we call our New Neighbours

Orientation Committee(l.32-4)

This feature can account for the fact that while this and the previous episode

examined have roughly the same number of moves (78-82) the present is much

lengthier, extending over 119 lines, with the former extending over only the half

66.

Lindner is exploiting the sentential constructions, and Walters

tolerance, since the latter chooses not to interrupt him as Beneatha does, in order

to bring forward the reason of his visit. This is also the usual pattern of

Chapter 3: Indirectness and black-mail status

22

conversations, since they tend to begin with the topic which is the reason for

the encounter and then move on to other topics (Coulthard 1985: 80).

Nevertheless, despite this tactic and Lindners promise to get right to the point

(l.48), he starts talking in line 22 and does not disclose his main purpose until

lines 88-9 and further (l.100-3), with a formal Inform, characterised by the

impersonality of the pronouns used. Instead of saying I-we do not want you to

move to our neighbourhood he utters the official our association is prepared

through the collective effort of our people, to buy the house from you at a

financial gain to your family. His difficulty in articulating his purpose and the

embarrassment that this causes him are evident in his choice of politeness

strategies and the number of ambivalent speech moves that he makes.

A prominent feature in Lindners politeness is the use of hedges.

Brown and Levinson (1987) consider hedges to function either as positive

(pp116-7) or as negative politeness strategies (145ff). The distinction is not

actually very clear, since they make the unfortunate choice of using the example

of sort of as hedging a predicate for both cases:

Positive politeness: You really are sort of a loner, arent you? (p.117)

Negative politeness: A swing is a sort of a toy (p.143)

In any case, hedges can have positive politeness since they serve to avoid a

precise communication of Ss attitude and the speaker can avoid being seen to

disagree with the hearer (pp.116-7); or they may carry negative politeness by

softening the assumptions connected to the conversation, not imposing on the

hearers face (p.146). In the text we find sort of (l.37, 38, 43), I guess (l.37),

probably (l.56), I think (l.59), I mean (l.27, 37, 46), now (l.93) and

modals.

Chapter 3: Indirectness and black-mail status

23

There is also the positive politeness strategy of you know (l.33, 71)

discussed earlier (p.13), the use of Im sure (l.48, 55) as a sign of optimism

and positive politeness (Brown and Levinson 1987: 126), while pessimism is

employed as well, a negative politeness strategy (ibid: 173) in the form of I

dont suppose (l.108). The frequent use of well (in 15 out of 46 moves) can

also be considered a hedge, but Schiffrins analysis of it seems to explicate more

successfully what is happening in the text:

Well is used with disagreements, denials, and insufficient answers

all responses which fail to show appreciation Well shows the

speakers aliveness to the need to accomplish coherence despite a

temporary inability to contribute to the satisfaction of that need in a

way fully consonant with the coherence options provided through

the prior discourse (Schiffrin 1987: 116, 126).

Lindner usually does not provide the answer expected and his speech is full of

breaches that hold back the progress of the topic. The following passage is

indicative of all the strategies mentioned above:

LINDNER: Well its what you might call a sort of welcoming

committee, I guess. I mean they, we, Im the chairman of the

committee go around and see the new people who move into

the neighbourhood and sort of give them the lowdown on the

way we do things out in Clybourne Park. (l.36-9, emphasis

added)

One final interesting case of Lindners use of politeness is found in lines

73-4 Anybody can see that you are a nice family of folks, hard-working and

honest Im sure. This could be considered as Brown and Levinsons (1987:

104) second positive politeness strategy exaggerate interest, approval, with H,

but it is not their canonical case; especially the use of Im sure, as it is placed

finally, seems more like a hedged than an exaggerated expression of approval. I

think that the purpose of this utterance can be better understood in relation to

lines 82-3 Now, I dont say we are perfect and there is a lot wrong in some of

Chapter 3: Indirectness and black-mail status

24

the things they want, and the second parts of Leechs (1983: 135-136)

Approbation and Modesty Maxims:

Minimize dispraise of other; Maximize praise of other.

Minimize praise of self; Maximize dispraise of self.

Hence, Lindner appears to praise the Youngers and dispraise the self the

community. Yet, as he has not actually maximised the praise for the Youngers

by the use of Im sure, equally, he does not maximise the dispraise of self.

With the use of now, some, and I dont say we are instead of the

categorical we are not, he attempts to satisfy two ends; observance of the

Maxims and at the same time, in a deeper level, maintenance of his positive

face.

Lindner makes seven Requests in this encounter and it is interesting to

note that six of them are very close to Informs while the one left is not clearly

articulated but merely a please (l.54). From the six mentioned, five have in the

subject position the speaker who is trying to make a Request which is not

overtly face-threatening and, thus, converts these to an informs about his

personal wishes. Nevertheless, they are moves perceived as Requests by his

interlocutors as well, and in this, he is more successful than Walter, whose off-

record strategy towards George clearly failed (see p.13).

Yet, the move causing the most problems of classification is the one

following Walters unmitigated Request Get out of my house, man (l.110):

LINDNER: What do you think you are going to gain by moving

into a neighbourhood where you just arent wanted and where

some elements well people can get awful worked up when

they feel that their whole way of life and everything theyve ever

worked for is threatened. (l.113-5)

Chapter 3: Indirectness and black-mail status

25

At a first reading the move seems like a Question, in the grammatical form of

wh-questions, prospecting an Inform, which will supply the missing piece of

information denoted by the wh-word (Tsui 1994: 72). Nevertheless, the

absence of a question mark, possibly denoting a questioning intonation, and its

lengthy elaborated formation suggest that what Lindner mainly wishes to

communicate are the presuppositions following where, and the implications of

threat that these presuppositions carry. Toolan (1997: 185) regards threats as

always implicitly or explicitly subordinate to some superordinate request so

threats are essentially requests, not offers. More recently, admitting the

existence of free-standing threats which are not so directly linked to an

immediately preceding Request (Toolan 2000: 197n) he classifies them as

Undertakings.

It is not easy to determine the extent of the co-text the theory should

allow, in which the preceding Request will be found. If only a few lines are

considered, a preceding Request will not be found. Even a greater context will

not provide us with a Request in this specific case, since Lindner is very

cautious and makes his proposal as an Inform (l.100-2). On the other hand, the

overall meaning and the reaction of the Youngers suggest that the Inform is

actually an implicit Request, and the move under examination encompasses a

reformulation of that Request.

The situation becomes more complicated if a reading of the move as a

warning is also considered. Warnings, in contrast to threats, are classified as

Informs (Toolan 2000: 181). Tsui (1994: 133) distinguishes warnings from

threats in the following way:

A warning is performed in the interest of the addressee, whereas a

threat is performed in the interest of the speaker himself.

Chapter 3: Indirectness and black-mail status

26

Yet whose interest the move serves is unclear, since it can be paraphrased both

ways (Warning it is dangerous for you to move there ; Threat We-they-I

7

dont want you to move there, so dont, or else). Nevertheless, Lindner does

not explicitly state the threat, nor commit himself on the certainty of his

statement. Hence, I think it preferable to regard the move as an Inform, which

has the hedging of a Question-wonder Why do this?, formulated in this way

because of reasons of politeness and social discipline

8

.

The episode ends with Lindner calling Walter son. It is intriguing to

see that after the discomfort and, albeit covert, hostility that he has manifested,

he chooses to close the encounter trying to soften the previous confrontation by

this kin address form that claims in-group identity. Furthermore, as a response

to Walters confident behaviour, he also tries to re-rank their social distance

and, especially, power:

when there is agreement about the normal address form to alters of

specified statuses, then any deviation is a message (Ervin-Tripp

1972: 236).

By calling him son, he claims in-group identity and the higher status of a father,

an older man. If the race factor is also taken into consideration

9

then this choice

seems more face threatening towards a black Walter, who is spoken down by

the white Lindner.

7

It is interesting to see how Lindner obscures agency, shifting between these three pronouns

and the agentless passive during all his moves.

8

An overt threat could possibly cause him and his committee a lawsuit at least.

9

Cf. the well known example given by Dr. Poussaint , taken from his interaction with a white

policeman: Whats you name, boy? (quoted in Ervin-Tripp 1972:225).

Chapter 3: Indirectness and black-mail status

27

Conclusion

In this scene, Walter tries to act as the man of the house, a status which

Beneatha refuses to acknowledge for about the first half of the episode. With her

insightful moves, she is the first member of the family to confront Lindner and

cause him unease. Thus, Beneatha claims her equal status in the family, with a

behaviour consistent with her feministic attitude and high aims she plans to

be a doctor present throughout the play.

Walters behaviour, during the first part, could, equally well, be

interpreted as mature, waiting for Lindner to explain himself, instead of

subordinate to Beneathas; very often an analysis can be interpreted in more

than one, opposite ways. These two readings may be interfaced, saying that

Walter is both being slightly more mature and, at the same time, overbalanced

by Beneatha. Proof of the latter is the fact that he tries twice to regain a higher

status by controlling her moves (l.44, 51) to succeed in his third effort (l.78).

Thereafter, Walter acts as the representative of the family.

Yet, the conversational maturity Walter exhibits is confined only in his

patience to await for Lindner to disclose his purpose, and the way he briefly

tries to re-rank the social distance and power between him and Lindner during

the phase of phatic communion; he does not show a generalised equally acute

conversational insight. In no case does he contest the constant techniques of

agency deletion and obscuration that Lindner employs. Only once does he ask

Lindner for clarification, after lines 76-7:

LINDNER: Today everybody knows what it means to be on the

outside of something. And of course, there is always somebody

who is out to take advantage of people who dont always

understand.

WALTER: What do you mean?

Chapter 3: Indirectness and black-mail status

28

But these lines are so overtly oblique and vague, that it would be strange for

anyone not to seek clarification. Finally, Walter allows Lindner to have the last

word in their encounter before he leaves the house.

These indications suggest that, despite the fragments of maturity

discussed, Walter does not exhibit particularly advanced conversational skills.

Chapter 4: Breaking and hearing bad news

29

Chapter 4: Breaking and hearing bad news; Man, Willy is

gone

After the turbulence that Lindner caused to the family, a state of

equilibrium seems to be restored. Walter, Beneatha and Ruth explain to Mama

the purpose of his visit. They then offer her gardening tools as a present, while

Travis gives her a gardening hat; both are gifts that will be useful in their new

house. The family is presented in a mood even merrier than the one they

displayed before Lindners visit. When the doorbell rings, Walter, who is

expecting his future business partners to bring him the news of their enterprise,

opens the door.

This is also the opening of the episode under examination (please see

Appendix 3) which commences with the breaking of one of the rules Laver

has formulated for phatic communion.

When one participant is static in space, and the other is moving

towards him, in whatever type of physical locale, then, unless there

are overriding special reasons, there seems to be a strong tendency,

both in Britain and America, for the incomer to initiate the

exchange of phatic communion (Laver 1975: 226).

Although Simpson (1989: 49) claims that the hypothesis and the reasons

provided by Laver seem a little speculative, Walter appears to wait for Bobo to

make the first move and to initiate phatic communion. After opening the door,

he has kept singing for some lines, and he is obliged to make the first move in

line 8, when Bobo remains silent. One of the explanations Laver offers to

support his rule is that the incomer declares in effect that his intentions are

pacific, and offers a propitiatory token (Laver 1975: 226). Bobo has to inform

Walter that all his money is lost and the announcement of bad news is an act

that by definition threatens the hearers positive face (Brown and Levinson

Chapter 4: Breaking and hearing bad news

30

1987: 67). Hence, his reluctance to engage in phatic communion, although a

friend, can be regarded as an indication of this hostile intention.

This reversal of the norm and violation of the expectations Walter had

are also suggested by the speech moves each participant makes.

Table 3 (from l.8 Wheres Willy, man?)

Informs Questions Requests Undertakings Total

Walter

Bobo

Ruth

17

26

1

14

1

1

11

6

0

3

0

0

45

33

2

81

Walter makes more moves; even if his final eleven moves are set aside because

they are addressed to non-participants, still Walter has two more moves than

Bobo. Furthermore something that the table cannot show Walter makes all

the first turns although it is Bobo who comes with the news. The latter is

supposed to be the important conversationalist, because of the information he is

carrying, but it is Walter who is presented in a position of power, since, it is he

who opens each stage of the conversation.

This episode, up to line 45, has much in common with a stereotypical

interrogation scene (if some features of familiarity between the interlocutors are

overlooked) with the roles of interrogator and interrogated filled by Walter and

Bobo, respectively. When the interrogation begins, after the brief interval of

phatic communion, in lines 10-13, Walters only moves are Questions and

Requests for addressee action. On the other hand, Bobos moves are mostly

Informs and three Requests for permission. Furthermore, Bobo appears to be

uncooperative from the first moment.

When Walter asks him in line 8 Wheres Willy, man? Bobo states the

obvious He aint with me and flouts the maxim of Quantity, since his

Chapter 4: Breaking and hearing bad news

31

contribution is less informative than requested. Walter could see by himself that

Willy was not with Bobo and this was what motivated his question. His next

move, after Walters Request in line 14, is a challenging one, as he supplies

an unexpected and inappropriate Act where the expectation of another has been

set up (Burton 1980: 151). Instead of answering Walter with an Inform, he

makes a Request. The same pattern exists in his later replies in lines 22 and 24-

26, where he is trying to change the discourse topic from the news to his

money.

Yet, when Bobo succeeds in getting Walters permission to talk about

the money in line 27 (What about the money you put in?) only briefly does he

seem to answer:

BOBO: Well it wasnt much as we told you me and Willy (He

stops.) Im sorry, Walter. I got a bad feeling about it. I got a real

bad feeling about it (l.28-9)

The last three moves are clearly violating the maxim of Relevance and thus are

locally incoherent. Walter, at this point of the conversation, lacks the required

shared knowledge in order to comprehend Bobos words. Equally uninformative

and incoherent, although exhibiting lexical cohesion, is Bobos next move:

WALTER: Tell me what happened in Springfield

BOBO: Springfield. (l.30-1)

Bobo is merely repeating Walters last words, flouting once more the maxim of

Quantity; his contribution does not offer any more information to his

interlocutor, than what he already knew

10

. However, Walter does not seem to

understand that there is an implicature conveyed by this flout. For two more

exchanges Bobo fails to give Walter the information that he needs. In line 41, he

10

It gives Ruth the opportunity to learn about Springfield, but once more, she is an unaddressed

participant in this interaction.

Chapter 4: Breaking and hearing bad news

32

flouts the maxim of Relevance and in line 43 he flouts the maxims of Quality

and Manner, providing again less information, and in an obscure way.

Walter finally succeeds in breaking Bobos resistance and learns the

bad news in line 46 (Willy didnt never show up). Bobos next turn taking in

lines 48-52, for the first time in the scene, violates the Quantity maxim by

giving more information than required. This signals the end of the

interrogation and introduces a crucial change in Walters conversational

behaviour that will be discussed later.

The fact that Bobo, although actually superior in being the knower

(Toolan 2000: 185), is behaving as subordinate in this scene, is also suggested

by his politeness strategies. His Request in line 17 is done with negative

politeness: the pessimism expressed by the modal could (Brown and Levinson

1987: 173) and the use of please. This seems an excessive use of politeness

between friends for a request as minimal as a drink of water. Yet, it can be

justified for two reasons; Bobo considers the imposition to be greater, because it

delays the announcement of the news Walter is so eager to hear. Secondly,

Bobo is about to deliver bad news, so his presence and information will be

considered to impose on Walters negative face. This is what Bobo actually

regards as significant and in this context, he reclassifies their social distance as

greater and, accordingly, the request for water as an FTA of larger imposition.

For the same reasons his next Requests are also presented in the form of

Informs about him having an obligation to do something, following an Inform

that presupposes shared knowledge and thus claims common ground (Brown

and Levinson 1987: 103):

BOBO: You know how it was. I got to tell you how it was. I mean

first I got to tell you how it was all the way (l.25)

Chapter 4: Breaking and hearing bad news

33

It is interesting to see that Bobo refers to his topic, the money, passing through

three formulations which gradually become lengthier/longer. This structure

reminds one of Jakobsons (1971: 352) remarks that

Morphology is rich in examples of alternate signs which exhibit an

equivalent relation between their signantia and signata. Thus, in

various Indo-European languages, the positive, comparative, and

superlative degrees of adjectives show a gradual increase in the

number of phonemes, e.g., high-higher-highest, altus-altior-

altissimus. In this way the signantia reflect the gradation gamut of

the signata.

The more Bobo is trying to succeed in his request, the larger this becomes.

Walters conversational power over his interlocutor is also suggested in

his two Questions in lines 21 and 23:

- There aint nothing wrong, is there?

- Man didnt nothing go wrong?

Fairclough, in his discussion of tag and negative questions, says:

Using negative questions is sometimes... like saying I assume that

X is the case, but you seem to be suggesting it isnt; surely it is?

we can say that power in discourse is to do with powerful

participants controlling and constraining the contributions of non-

powerful participants (Fairclough 1989: 46).

Walter holds this power until line 52, when he finally learns the truth Man,

Willy is gone. Bobo for the first time in this scene does not violate the co-

operative principle, since he observes all the maxims; he really does not know

where Willy is and his contribution is such as is required (Grice 1975: 45).

Nevertheless, Walter is now trying to find an implicature:

WALTER: (a) Gone, what do you mean Willy is gone? (b) Gone

where? (c) You mean he went by himself. (d) You mean he went

off to Springfield by himself to take care of getting the licence

(Turns and looks anxiously at RUTH.) (e) You mean maybe he

didnt want too many people in on the business down there?

(Looks back to BOBO.) (f) Maybe you was late yesterday and he

just went on down there without you. (g) Maybe maybe hes

Chapter 4: Breaking and hearing bad news

34

been callin you at home tryin to tell you what happened or

something. (h) Maybe maybe he just got sick. (i) Hes

somewhere (j) hes got to be somewhere. (k) We just got to

find him (l) me and you got to find him (m) We got to!

(letters added)

Walters Informs (c, d, e, f) are statements about B-events, according to Labovs

classification:

Given any two-party conversation, there exists an understanding that

there are events that A knows about, but B does not; and events that

B knows about but A does not; and AB-events that are known to

both... If A makes a statement about a B-event, it is heard as a

request for confirmation (Labov 1972a: 124).

His next moves (g, h, i, j) are statements about what could be called C-events,

since neither of the two members has any knowledge about them. Labov and

Fanshel introduce the class of D-events, Disputable events, and state the rule of

Disputable Assertions:

If A makes an assertion about a D-event, it is heard as a request for

B to give an evaluation of that assertion (Labov and Fanshel 1977:

101).

Yet, the term C-event is preferred, because Walter does not seem to anticipate

some kind of evaluation from Bobo, and makes mere speculations. In his effort

to find a reasonable explanation, Walter violates the Quality maxim, in g and h

saying something for which he lacks evidence, while in i and j he flouts the

Quantity maxim, stating the obvious; everyone is somewhere, but what he

wishes to implicate is overtly stated in k, l and m.

These last moves are interesting in that, according to the framework

employed, they are intermediate. They imply shared action and mutual benefit,

and by those considerations are both Requests and Undertakings (Toolan 2000:

180n). A similar case was discussed in page 13 (Walter to George: we ought to

sit down and talk sometimes) but it was characterised as a Request, since it was

Chapter 4: Breaking and hearing bad news

35

actually in Walters interest. Nevertheless, the moves under examination will

profit both participants, as both lost their money. This also justifies the use of a

more committing deontic modality (got to) instead of the weaker modality of

ought to.

After this large turn of talk, Bobo makes his first initiating move Whats

the matter with you, Walter? (l.62). This is a Request similar to those discussed

in page 15, made by Ruth, when Walter was behaving like a disobedient child.

Walter here also appears out of control and then engages in a long stretch of

talk. It is Walters turn, at this time, to make four Requests in order of gradual

augmentation already noted for Bobo:

WALTER: dont do it Please dont do it Man, not with that

money Man, please, not with that money (l.65)

But it is doubtful whether the moves can be considered as goal directed. His

moves addressed to Willy are obviously ineffectual, since Willy cannot hear

him. His prayers, too, could be regarded equally useless to the judgement of an

atheist.

Nevertheless, these moves, albeit not communicatives at the level of the

discourse of the play, can be considered to become messages about the

character at the level of discourse which pertains between author and

reader/audience (Short 1989: 149). In the light of this, the passage functions to

delineate Walters transformation from an interrogator to a desperate child who

thinks aloud, talking to himself.

Conclusion

It is interesting to see that the patience exhibited by Walter in respect to

Lindner (the previous scene examined), vanishes in this scene. This may be

Chapter 4: Breaking and hearing bad news

36

explained by the fact that Walter is so anxious to hear the news, which will

change his life, that he does not have the self-control to be patient. Nevertheless,

Bobo is a friend at least more than Lindner, a total stranger and it is quite

striking for Walter to act as an interrogator towards Bobo and impose on him in

that way.

Yet, even in his role as an interrogator Walter does not seem to be totally

successful, in getting a clear confession from Bobo:

BOBO: Thats what Im trying to tell you I dont know I

waited six hours I called his house and I waited six

hours I waited in that train station six hours (breaking into

tears.) That was all the extra money I had in the world

Looking up at WALTER with tears running down his face.

Man, Willy is gone.

Of course, the truth can be recovered from the above words Willy is gone with

our money, but it is not directly stated.

The scene closes with a devastated Walter, who starts speculating to end

up in a soliloquy typical of child behaviour or of mentally ill people. To think

aloud is a phase through which all people pass in their early childhood. But

when met in adults, this behaviour is considered as a sign of mental disorder.

So, the ending of this scene presents Walter having regressed from whichever

maturity he exhibited in the previous scene.

Chapter 5: Self identity and inference

37

Chapter 5: Self identity and inference; My father almost beat

a man to death

The final episode to be examined (please refer to Appendix 4) takes

place only a few lines before the end of the play. After Walter has learned that

all the money he intended to invest in the liquor store is lost, he calls Lindner

back in order to accept his offer and, thus, balance the financial loss caused by

his failed plans. But, the other members of the family do not agree with his

decision when he announces it to them and a very tense and emotional scene

ensues, where Walter mimics an Uncle Tom complete with grotesque dialect

and gestures (Washington 1988: 122) and Beneatha denounces him, while

Mama deplores her childrens behaviour. All these precede Lindners

appearance in the doorway.

The primary speech moves made by each participant are the following:

Table 4

Informs Questions Requests Undertakings Total

Walter

Lindner

Mama

Ruth

Beneatha

17

11

4

1

1

1

2

0

0

0

0

1

7

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

18

14

11

2

1

46

In contrast to his first visit, Lindner has been invited by Walter and thus

Walter is expected to give the reasons initiating the present encounter. This

partially justifies the fact that Walter makes more moves than his other

interlocutors, who implicitly give him permission to declare those reasons.

Nevertheless, the main participants seem to have equal conversational rights in

this meeting, judging from the number of their moves. In the first visit, the three

main participants (Lindner, Walter, Ruth) had 40, 20, 12 moves respectively

Chapter 5: Self identity and inference

38

(see p.18). In this episode the number of the moves made by Walter, Lindner

and Mama are more equal (18, 14, 11). Beneatha makes only one move,

something that is interesting compared with her conversational behaviour

previously. Ruth, the least participating member in the previous conversations,

makes two moves, only one more than Beneatha, both of which are placed in the

opening phase of the meeting.

Lindners first attempts to engage in interaction are unsuccessful. His

Inform in line 4 is the first part of an adjacency pair of greeting that is left

unanswered. Sacks argues that the absence of the second [part in an adjacency

pair] is noticeable and noticed and offers examples of peoples complaints such

as I said hello, and she just walked past (reported in Coulthard 1985: 70).

Lindners two Questions in lines 14, 15 are also without response. Ruths and

Mamas following stretches of talk (l.18-25), are addressed to Travis and

Walter, and the latter is the first to address Lindner directly, in line 28. From

then on and until line 60, where Walter withdraws from the conversation,

Lindners moves are either Acknowledgements to Walter (l. 31, 34, 38, 51), or

attempts at Informs that are disrupted by Walter (l.42, 47).

His second move, after Walter has withdrawn from the conversation, is a

Request addressed to Mama Then I would like to appeal to you, Mrs

Younger (l.62). This is done with what Leech calls a self-reporting

utterance which is the case

where the speaker uses the metalanguage of speech-act verbs for

describing his own discourse (Leech 1983: 225-6).

Having failed with Walter, Lindner turns to Mama and explicitly states his

Request in an attempt to convince her.

Chapter 5: Self identity and inference

39

In his previous visit, Lindners final word was the address form son

directed to Walter. In this episode, while Lindner feels that his aims will

succeed, he addresses Walter as Mr Younger, paying respect to a distant yet

equal interlocutor as Brown and Ford (1964: 241) note: adults of equal status

[begin their encounter] with Mutual Title plus Last Name. This is the same

form of address used for Mama as seen in the previous paragraph. But it is

interesting to note that once more, when his expectations are defeated, he

addresses the Youngers collectively, as you people, in an Inform similar, albeit

more vague, to the one discussed in pages 24-26.

I sure hope you people know what youre getting into. (l.69-70)

Lindner again chooses to communicate his warning through the

presuppositions of the subordinate clause. He presupposes that the family is

getting into something, which certainly is not their new house. He flouts the

Quantity and the Manner Maxims since he gives less information than needed in

an obscure way. The something the family is getting into is not clearly stated.

It may allude to a previous presupposition that people can get awful worked

up (p.24), which was equally under-informative. In both meetings, when

Lindner sees the (to him) undesirable decision of the Youngers he retreats into

Informs charged with implicatures of warning-threat.

Walters conversational behaviour can be divided in two stages. In the

first one (l. 28-46) his talk abounds with the use of well and I mean. Both

have been discussed in the analysis of the previous encounter between Walter

and Lindner, where they were features of Lindners talk. As a reminder, it is

sufficient to say that well was characterised as a marker of temporal inability

of the speaker to proceed entirely unproblematically in the expected coherent

Chapter 5: Self identity and inference

40

way (p.23), and I mean was characterised as a hedge indicating politeness

(p.14). The second stage (l. 52-68) is where Walter manages to utter, in a

categorical way, the decision of his family to move to the new house.

Walters moves can be better understood, if they are examined in

isolation from the rest of the text in example, that is separated from Lindners

moves and the playwrights comments:

WALTER: Well, Mr Lindner. We called you because, well, me

and my family well we are very plain people I mean I

have worked as a chauffeur most of my life and my wife here,

she does domestic work in peoples kitchens. So does my mother.

I mean we are plain people. And uh well, my father, well

he was a labourer most of his life And my father My father

almost beat a man to death once because this man called him a

bad name or something. You know what I mean? What I mean to

say is that we come from people who had a lot of pride. I mean

we are very proud people. And thats my sister over there and

shes going to be a doctor and we are very proud What I am

telling you is that we called you over here to tell you that we are

very proud and that this this is my son, and he makes the sixht

generation of our family in this country, and we have all thought

about you offer And we have decided to move into our

house because my father my father he earned it for us, brick

by brick. We dont want to make no trouble for nobody or fight

no causes but we will try to be good neighbours. Thats all we

got to say. We dont want your money.

This could be considered as a narrative, with a minimal narrative (Labov

1972b: 360) embedded at the heart of it, the highlighted text. Yet as a narrative,

it has two uncommon characteristics. First, the great extent of the Orientation,

which functions, among other things, to identify the persons involved in the

narrative (Labov 1972b: 364). Walter commences the narration with a we

which he then explicates, by referring not only to the people involved but their

occupation as well.:

Chapter 5: Self identity and inference

41

Me (Walter)

Wife

Mother

Father

Sister

Son

Chauffeur

Domestic work

Domestic work

Labourer

Future doctor

Sixth generation in the country

Only after he has mentioned each member of the family does he proceed in the

Complicating action and the Resolution, found in the minimal narrative. His last

two moves can be considered as a very definite Coda thats all we got to say

and the abstract, stating what the narrative is about [and] why it was told

(Labov 1972b: 370) we dont want your money.

Second, it is a strange narrative, in that it is about what is going to

happen, and not a recapitulation of past experience. Although its minimal

narrative is placed in the past, it actually looks to the future, as the decision

taken is a decision concerning future action, the expression of an attempt to

shape and control it. Walters reference to his sister is also a future defining one,

shes going to be a doctor.

For this reason, it may be better to perceive his talk as a speech, a

declaration of some sort. The declaration of future acts concerning the family

and Beneatha are already mentioned. The part that precedes the underlined text

has two main recurrent themes; we are plain people and we are very proud.