Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

The Managers Role in Safety

Caricato da

ranadheer3370 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

33 visualizzazioni16 paginedescribes roles of manager in safety department

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentodescribes roles of manager in safety department

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

33 visualizzazioni16 pagineThe Managers Role in Safety

Caricato da

ranadheer337describes roles of manager in safety department

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 16

Managers: Expanding Their Leadership Role in Safety

Rosa-Antonia Simon Carrillo

Published 6/98 Professional Safety Magazine

Most managers do care about the safety of their organizations, but some of

them are at a loss about what to do to show that concern and manage safety

effectively. For example, a group of high ranking managers from a Fortune 500

company gathered to hear the results of an employee survey and extensive audit of

their internal safety management practices. They were surprised by employee

perceptions that management was invisible, did not walk the talk in safety, was

unresponsive to safety concerns, and had unclear goals and expectations for safety

performance. Upon hearing this feedback, they looked at each other and said,

Weve done everything we can think of to show our concern and demonstrate that

safety is important. We dont know what to do anymore.

Managers facing this dilemma can find new direction by examining and

changing their own beliefs about what works in safety and taking a leadership

position in creating a new safety culture.

Safety Management Approaches that Dont Work

American management is discovering that traditional approaches to safety

performance no longer suffice. We will examine five of them in this section,

beginning with the three most frequently used--focusing on operator error, spending

large sums on technical solutions, or using injury-related statistics as the only way to

measure performance.

Accident investigations that focus on operator error are viewed as blame-

fixing by employees and often fail to take into account systemic root causes.

Technical solutions only take the organization so far. Installing new guards or

equipment helps reduce some injuries, but cannot prevent some of the most common

accidents. What guard or procedure will make people pick up a 2 x 4 in the

middle a walkway or hold a handrail going down stairs? Finally, the single minded

use of safety numbers as a performance indicator has created a backlash among

1997 Rosa-Antonia Carrillo

Managers: Expanding Their Leadership Role in Safety

employees who believe that Management doesnt care about us. They only care

about the numbers.

There are no simple solutions to this quandary. Let us look at two more

common approaches to improving safety where results are less than satisfactory. One

is mandated compliance and the other is the use of incentives.

Mandated compliance, if it is going to work, must be backed by tight

policies, procedures and discipline. Without consistent enforcement this approach is

doomed to failure in most worksites because production deadlines are stronger

influences on behavior than policy and procedure. A successful example of

mandated compliance exists in the US nuclear industry. There have been no new

incidents since Three Mile Island. Control has been achieved at a high cost,

however; in order to comply with regulations. The ratio of administrators to

operators is about 100 to 4 and plants found in violation have been shut down, at a

cost of millions of dollars. Outside of the nuclear industry, businesses cannot remain

competitive with that kind of overhead, but that is what it takes to rule effectively by

bureaucracy.

Another frequent remedy is installing rewards and incentives to modify

safety behavior. There are no known correlations between typical awards such as

gift certificates, t-shirts and jackets and safety performance.

1

Some companies have

installed profit sharing and substantial bonuses related to incident rates which do

lower statistics, but the jury is still out on whether or not it actually improves safety,

since people may not be reporting injuries. Peter Drucker also observed, Economic

incentives are becoming rights rather than rewards. Merit raises are always

introduced as rewards for exceptional performance. In no time at all they become a

right. The increasing demand for material rewards is rapidly destroying their

usefulness as incentives and managerial tools.

2

At best award and incentive

1

Simon, Rosa Antonia, An Open Systems Approach to Managing Safety Performance,

Unpublished Thesis, Pepperdine University, 1993.

2

Drucker, Peter, Management Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices, Harper and Row, p.

239.

1997 Rosa Antonia Carrillo 2

Managers: Expanding Their Leadership Role in Safety

programs give temporary boosts to safety programs. Experience has shown they are

not sustainable.

It is very difficult to get beyond these traditional approaches. Most

managers were raised to believe that the way to manage for excellence was to tell

people exactly what to do and then follow up. Re-engineering came about and we

thought we could engineer people into perfect performance. Behaviorists arrived

and they told us we could modify employee behaviors. But you can not direct or

modify people into perfection; you can only engage them and influence them to want

to do perfect work. That is why the answer to achieving safety excellence lies in

leadership and employee empowerment.

Empowerment: A Positive Experience

There are plants that have achieved OSHA Star status under the

Voluntary Protection Program with near perfect safety records for years at a time.

They achieve those results initially because leadership guides and provides resources

during a three-to-five year process that empower workers to take responsibility for

safety, making it a personal mission. There are regulations, policies and procedures,

but those elements are not different from those found at poorly performing plants.

Good performance comes from the hundreds of workers who understand their role in

safety, the whys of safety and that safety is up to them.

Achieving this level of excellence takes a lot of work. Tom Moeller, an oil

refinery manager, talked about his experience in bringing a refinery into the STAR

program.

When I came to Beaumont this plant was in serious trouble.

We had lost 90 million dollars. Our expenses were in the fourth quartile

on the Solomon survey which basically said we were at the bottom of the

heap of all the refineries in the United States. We are today, 1996, in the

first quartile of the Solomon Index. We have the lowest cost structure of

all the refineries in the world. We have one of the best safety records of

all the Mobil refineries in the world. At the same time we downsized

1997 Rosa Antonia Carrillo 3

Managers: Expanding Their Leadership Role in Safety

400 people. Our culture is far better today than it was in 1992. When I

came down here I only knew one program to do and that was the

Voluntary Protection Program (VPP).

If you improve safety the whole organization improves, but if

you leave out the safety part, the rest of the organization wont stay

improved. We did it by setting up a lot of teams among our employees.

There is a team there that worries about sling inspections, inspections of

our cranes, making sure that we meet all the OSHA standards, making

sure that the repairs are made when they should be made, and that

preventative maintenance is done. There is a team in the weld shop and

there is a team pretty much everywhere that says to the hourly folks and

supervisors, This is the OSHA standard. We also give them the

freedom to spend the money to do what you have to do and to set people

aside to get the job done.

We spent a fair amount of money. The other side of the coin is

our heavy equipment reliability is way up. There are big pieces of

equipment that might cost a million or half a million dollars so you dont

want them out of service much of the time or you have to replace them

by renting a piece of equipment. There arent any injures. While we

spend a lot of money to train people, the workers now have

responsibility for it. They spend money for the appropriate repairs. I

think we probably made it back several times over.

Im not trying to make it sound easy. We spent a lot of time

establishing a relationship with the workmans committee. We took

away some of things that really bothered people a lot. When I came

down here we had hundreds of grievances, some 15 years old. So we set

up a couple of junior employees and a couple of management employees

(front line employees) in a room and said, you all develop

recommendations to resolve these grievances. We paid people

sometimes for a grievance that was ten years old. It might have been

$200 or $300, but we paid them and just got rid of it. We set out to build

1997 Rosa Antonia Carrillo 4

Managers: Expanding Their Leadership Role in Safety

trust. It doesnt mean we didnt have hard negotiations. We had very

hard negotiations and at one point I thought we were going to have a

strike. We fired the president of the union along the way. So its not like

it was peaches and cream, it wasnt.

In these plants each time an unscripted event comes up--a leak, a storm, a

customer demanding faster service--it is up to the individual to make the right

choice. The examples of these plants confirm that ultimately, we cannot rely on

procedure manuals. We can rely on peoples intelligence and their commitment to

doing the right thing, but people have to know what right means. They have to

know what safe really means. This can only be achieved through education,

training and dialogue.

Establishing Common Values, Goals and Standards

A culture where people can be relied on to make the right choice is one

where each person in the organization holds the same high standard for safe work

habits, orderliness and accountability. Once these standards are internalized, they

direct behavior, creating a culture that is self enforcing and supports safety

excellence. Creating such an organization begins with two steps: First, is the

involvement of the total employee population. The second is exploring the current

beliefs and assumptions guiding peoples behavior, and the organizational systems

that perpetuate those beliefs. This is necessary because eradicating accidents from

the workplace represents a fundamentally different way of thinking about work. For

centuries accidents have been an accepted cost of doing business. Changing that

assumption requires upsetting the status quo and success does not come easily. There

is great personal risk of failure.

We know that most plant managers or corporate executives would not

sacrifice the health of their employees in exchange for production. They would never

say, Do the job unsafely to meet this deadline. Yet, often accident investigations

reveal that employees work off the assumption that it is more acceptable in their

organization to take a safety shortcut than it is to miss a deadline. Employees often

1997 Rosa Antonia Carrillo 5

Managers: Expanding Their Leadership Role in Safety

state that they feel implied pressures to meet deadlines while logistic planners and

supervisors scratch their head wondering how a casual comment that it would be

good to get something done by a certain time got translated into a rush job. Their

surprise shows a lack of cultural awareness. They do not understand the power of

their position and the long-standing expectations that unconsciously drive peoples

behavior.

If we are going to commit to eliminating job injuries as a normal part of

work, we are going to have to change peoples basic assumptions about what it

means to do the job right. We will have to add the word safe to the current

expectation of on time and meeting specs. To do this we have to turn to the

people who do the work. We have to engage them in setting up new standards that

challenge the status quo. We have to create a new safety culture.

The Dynamics that Shape Culture

In guiding a culture change effort, managers have to understand the

importance of leadership in creating, changing and shaping culture. In

Organizational Culture and Leadership, Edgar Schein goes so far as to say that,

Without leadership, groups would not be able to adapt to changing environmental

conditions.

3

When leaders understand culture, they can use it or surmount it. If

leaders do not understand culture, it will manage them.

The most powerful cultural forces are invisible: They are the norms, beliefs

and assumptions that influence safety behavior much more than guards, policies and

procedures. We will begin by defining norms and then move on to the deeper, more

complex assumptions that rule culture.

Research on the importance of norms (defined as any uniformity of attitude,

opinion, feeling, or action shared by two or more people) in determining attitudes

towards production is well documented. The same phenomena, convergence and

3

Schein, Edgar. Organizational Culture and Leadership, Jossey Bass: San Francisco,

1991. p. 317.

1997 Rosa Antonia Carrillo 6

Managers: Expanding Their Leadership Role in Safety

cohesion, which shape attitudes and/or norms towards productivity, also apply to

safety.

Briefly, convergence is the tendency of human beings to adopt the point of

view of people whom they perceive as part of their group. Studies show that even if

a group member initially disagrees with the group, given enough time he or she will

adopt the groups point of view (or leave the group). The second force, cohesion, is

our tendency to form groups with people we like and who hold opinions, attitudes,

and ideas similar to our own.

This research on norms has deep implications for understanding how safety

attitudes form and what one has to do to change them. Currently, supervisors and

managers rely on training and rewards to change people. However, change does not

take hold when the newly trained individual returns to a group with unchanged

norms. He or she will revert to the former behavior. An example would be someone

attending a clinic to stop smoking, then returning to a home and work place where

everyone smokes. There is a high probability that that individual would resume

smoking. Thus, to change organizational behavior supervisors and managers must

learn to shape group norms as well as offer individual training.

If it is difficult to change an assumption where medical evidence is

abundantly available, as is the case with smoking, imagine the difficulty in changing

to an assumption that is counter intuitive. One such example is changing the belief

that safety is the safety coordinators responsibility. Because safety professionals

are the experts, they are commonly viewed as the most likely people to enforce

safety and correct hazards. In reality, line management holds the authority and

resources to enforce safety and line workers are the most likely to spot hazards, but

the old belief is held in place by years of experience and tradition.

An organizations safety culture, then, is mostly made up of what people

believe is importantthe norms, assumptions and beliefs that effect that peoples

choices and actions. Should we rush to meet this deadline, or is it okay to stop and

take safety precautions? Is it okay to remind someone to wear their hard-hat or will I

be told to mind my own business? The answers are influenced by the safety culture

of the organization.

1997 Rosa Antonia Carrillo 7

Managers: Expanding Their Leadership Role in Safety

The following section presents certain principles and dynamics confirmed

through experience, research and observation of effective culture change leadership.

Leadership Roles

A change leader uses both his person and position to create change. It is not

possible to change an organizational culture without first changing yourself. Culture

change requires letting go of some of your deepest beliefs about how the world

should and does operate. Willingness to enter into unknown areas and lead others

requires a personal commitment to examining and correcting assumptions or beliefs.

Leaders need the ability to raise and question beliefs that everyone else

takes for granted. We need to look ahead and assess when these beliefs are wrong

and will hurt their organization. Then we need to articulate new assumptions and

sell them. An example of leaderships failure to do this is the US car manufacturing

industry. Leaders failed to see customer needs for gasoline economy and higher

quality. They did not change their long-held assumption that US cars would

continue to dominate the market. Only when US auto makers acknowledged the

need for change and began to close the gap in quality and cost-effectiveness, did they

begin to regain market share.

Once you have changed your own assumptions, if you choose to influence

others to change, you are assuming a leadership position. The confusion that usually

follows the surrender of old assumptions is a form of energy that can be channeled to

take the organization to the next stage. People are looking for a new path, making it

possible for leaders to influence their direct reports via their clear vision and

emotional certainty. The transition is completed when leaderships vision is

translated to reality by the rest of the organization.

Leaders in formal positions of authority are responsible for organizing the

activities around the change process. Grassroots leaders influence the level and

speed of acceptance of change. Senior managers characteristically assume

sponsorship roles and typically are the ones who sanction as well as provide

financial and moral support for change efforts.

1997 Rosa Antonia Carrillo 8

Managers: Expanding Their Leadership Role in Safety

Top management support is not enough to drive a culture change. One

division manager was appalled to get feedback that the universal belief among his

technicians was that deadlines took precedence over safety concerns. As division

manager he personally attended safety committee meetings and made safety an

important issue at his staff meetings. What was wrong? While he personally acted

in accordance with his beliefs, he had no structures that held his direct reports or

those under them accountable for communicating or enforcing a common set of

safety standards.

Part of the answer is revealed in a nine-year study tracking change

implementation efforts. Production units within the same facility experienced wide

variances in the successful implementation of change efforts supported by top

management. The study showed clearly that first-line supervisors and mid-level

managers were essential to making the changes work. Successful units had frequent

dialogue forums to discuss the change and more efforts to learn from the units

experiences with the changed approaches..

4

Change cannot be implemented without first-line and mid-level

management buy-in. They are the ones who cope with the changes initiated higher

up. Their skills as change managers often make the difference between successful

and unsuccessful change. Traditionally, their job is to guide, harness and control the

chaos and distress brought about by change, but there is a better way to manage

change: gain employee buy-in for the change through the use of grassroots

leadership.

Developing grassroots leaders through participation and empowerment

smoothes out and speeds up the culture change. As illustrated in Moellers

experience described earlier in this article, employees need a lot of training and

education to be successfully empowered in safety. By utilizing grassroots leaders, a

managers role can change from controlling chaos and distress to guiding and

supporting the knowledge, creativity and efforts of the people doing the work to

4

Tenkasi, Mohrman, S.A. & Mohrman,A.M. Jr. Accelerated Learning During

Transition. In Mohrman, S.A., Galbraith, J.R., Lawler, E.E. III & Associates. Tomorrows

1997 Rosa Antonia Carrillo 9

Managers: Expanding Their Leadership Role in Safety

meet organizational goals. Access to the grassroots culture makes the difference

between success and failure in adapting to a quickly changing environment.

To manage a grassroots culture change effort, managers must be able to

question, listen, experiment, tolerate ambiguity and convince people to examine

options that might require painful choices without a guaranteed solution. Getting

others to enter into unknown areas requires a personal commitment on your part to

engage in examining and correcting your own assumptions. A change leader

assumes the responsibility to influence, guide and support others to see the world

differently. There is no way to do that unless you have adapted to the change

yourself.

The leadership assumptions in the next section will assist you in clarifying

your own position on the culture change path.

Six Steps Towards Change in the Management Culture

For those leaders who have not addressed the fundamental assumptions that

affect safety in their organization, we offer the following six-step action plan to be

implemented through a series of dialogues. A summary of the process is shown in

Figure 1 followed by a rationale for each phase.

1. Articulate the assumptions that managers/supervisors work under when

making decisions about safety. Leadership must be aware of changing conditions

and determine whether or not assumptions continue to be valid. When an

assumption ceases to be valid, leadership must search for new answers and embed

new assumptions into the culture. This principle applies to both the business and

interpersonal arenas.

In business the global economy is driving many paradigm shifts that require

major changes in how people and work are managed. Figure 2 lists past assumptions

and the future assumptions that are driving business leaders today. Our safety

management assumptions must adapt to these same forces to maintain alignment

Organization: Crafting Organizations for a Dynamic World. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. In

Press. 1997

1997 Rosa Antonia Carrillo 10

Managers: Expanding Their Leadership Role in Safety

with business practices. Figure 3 lists some of the past safety assumptions and what

they need to become to support new business directions.

Figure 1

Leadership Assumption Dialogues

Step Activity Purpose

1. Articulate the assumptions that

managers/supervisors work under when making

decisions about safety . Some of these beliefs are

never articulated but carried in the culture as

implied . (i.e., They never say put production

ahead of safety, but if you dont meet a deadline you

never hear the end of it.)

Bring out covert

beliefs that drive

individuals to take

unnecessary risks.

2. Prioritize the invalid assumptions according to their

negative impact on the safety culture.

Leverage your

resources

3. Analyze each invalid assumption to determine

causes:

1. How did the old assumption become part of the

culture?

2. Is it still valid?

3. What would leadership have to do differently to

embed the new safety assumptions?

Acknowledge those

assumptions that

use to be valid and

managements

contribution to

keeping them in

place.

4. Articulate the new assumption and the driver or

motivation for change.

Identify new

direction and

business case for

making the change.

5. Group agreement on meaning and intended

consequence of new assumption

Establish

foundation for new

culture

6. Action planning and implementation Going from idea to

application

Figure 2

Past and Future Business Assumptions

1997 Rosa Antonia Carrillo 11

Managers: Expanding Their Leadership Role in Safety

Past Business Assumptions Future Business Assumptions

Hierarchical organization Flat Organization

Profit Margin Profit and Customer Satisfaction

Power = Capital Power = Knowledge

National Scope Global Marketplace

Focus on Individual-Based Skills Focus on Team-Based Skills

Figure 3

Safety Leadership Assumptions Must be Aligned with Changes in

Organizations

Past Safety Assumptions New Safety Assumptions

Safety manager as doer Safety professional is a facilitator/consultant

Safety is an expense Safety is as integral to profit as quality and

production

Monocultural training materials and

approaches

Cultural diversity affects approach to safety

management

The safety department is responsible for

safety

Trained and educated employees perform

safety functions previously performed by

"experts"

On a personal level, some beliefs that hold back the culture are never

articulated but carried in the culture as implied. Examples are, They never say,

Put production ahead of safety, but if you dont meet a deadline you never hear the

end of it. Another manager once said, I dont know why we have so many

accidents since none of the employees ever do any work! Both of these

assumptions almost insure failure in starting any new safety program and must be

addressed before progress can be made.

1997 Rosa Antonia Carrillo 12

Managers: Expanding Their Leadership Role in Safety

2. Prioritize the invalid assumptions according to their negative impact on

the safety culture. Pay special attention to the assumptions that separate safety from

the real work. One of the most common complaints from safety committee

members is that, Safety projects take a back seat until we have some free time

Another common issue is the inconsistent definition among managers on the

questions, How safe is safe enough? ; What policies are we going to enforce?;

What do we really mean by safety first?

3. Analyze each invalid assumption to determine causes. Ask how and

why the old assumption became a part of our culture and what would leadership have

to do differently to embed a new a assumption. It is important to acknowledge that

past assumptions may have been built on experience, but may no longer be valid.

Managers have to understand their contribution to the problem before they can

change their behavior and create a new culture. Later they can engage employees in

similar dialogues so that they have an opportunity to air differences of opinion and

realize that they too play a role in keeping work out assumptions in place.

4. Articulate the new assumption and the driver or motivation for change.

Do not accept superficial statements like safety first. Many organizations put

slogans on the walls, but few have leaders at all levels of the organization living up

to them. The new assumption has to be reality driven. You have to know which

business reasons are sufficiently strong to motivate people to adopt higher standards

in safety. If a lasting change in the way people work is the goal, a workable

assumption is, Safety standards are an integral part of production. The latter

statement will spark a number of organizational changes such as defining a common

set of safety standards adhered to by everyone or rewriting production specs to

include safety conditions.

5. Get management agreement on the meaning and intended consequence of

the new assumption. Never assume that writing a station order or procedure

constitutes changing the culture. How many plants have requirements that work

orders have three or more signatures before they are implemented? How many

people read the work order before signing? How many supervisors assign others to

sign for them because they are away in meetings about really important matters

1997 Rosa Antonia Carrillo 13

Managers: Expanding Their Leadership Role in Safety

regarding the business? Culture change will take place as managers engage in

meaningful dialogue about the new assumptions, buy into them because they see a

real business need for them, and demonstrate them through their actions. This is

unlikely to happen without an organized, concerted effort to involve all supervisors

and managers in translating the new assumptions into their own work. Once

management is in agreement, they may formulate action plans to gain employee buy-

in for the new assumptions.

6. Put action plans that support the new assumptions into the business

plan. If the business plan is used, this is the most effective place to integrate safety

improvement actions into the business. Organizations with excellent safety cultures

usually empower employees to participate in designing the solutions to safety

problems. Care has to be taken to keep supervisors and middle managers in the

communication loop to prevent disenfranchisement of any group.

These six steps can be implemented through Leadership Assumptions

Dialogues where you assess your current assumptions about safety, and identify the

new, desired assumptions to achieve the next level of safety excellence. Once the

top level of management has completed the process, the next step is to involve the

rest of the managers, supervisors, and eventually employees in similar dialogues.

Conclusion

New assumptions are often met with fear or cynicism: fear because

fundamental changes may threaten job security or loss of power; cynicism because

safety efforts may be viewed as flavor of the month. Nevertheless, leaders need to

be bold and take on difficult challenges.

The safety manager of a 2000-person nuclear power plant took the kinds of

risks we are talking about, challenging his companys traditional practice of setting

measurable and achievable accident goals. By those standards, he argued, they could

meet their .13 (11 loss times) goal and see eleven employees die on the job that year.

Not exactly the kind of value statement they wanted to make to their employees.

Instead, he proposed a goal of zero accidents, facing the doubt and criticism of

management. Ultimately, he won their support; and though they have not yet

1997 Rosa Antonia Carrillo 14

Managers: Expanding Their Leadership Role in Safety

reached their ultimate goal, accidents at the plant are down fifty percent and, best of

all, the culture is changing and accidents and injuries are no longer considered

acceptable.

This is one example of risk taking. Culture is local and we cannot replicate

anyone elses exact process for success. Benchmarking and experimentation will

help you find your own way, but this requires eliminating the fear of making

mistakes. With so many paths available, which one to choose? Where should you

spend your resources? Of all the resources, time is the scarcest. Changing the way

people think is time consuming. You and those you invite to engage in these

dialogues might feel it is a waste of time, that other issues seem more immediate. By

what criteria? Customer focus is important, but if you are going to lead, you need to

look ahead, beyond fire fighting. That is the role of the leader; to look into the future

and forecast what will be needed to survive, to adapt. Keep in mind that any

improvements you make in helping people achieve a common understanding of

safety standards for safety will positively affect all areas of your enterprise.

1997 Rosa Antonia Carrillo 15

Managers: Expanding Their Leadership Role in Safety

Quickie Safety Culture Assessment

Check off the statements that describe the beliefs/assumptions in your facility

culture:

1. Employees ignore or bypass technical improvements.

2. Employees disregard new policies and procedures.

3. Our accident numbers have been flat.

4. Many workers compensation claims are not legitimate.

5. Employees are often defensive and evasive during accident investigations.

6. Employees file many unnecessary and illegitimate grievances.

7. Employees are resistant to our safety initiatives.

8. Employees do not appreciate the work we are doing to improve our safety

performance.

9. Workers do not believe that we have their best interests at heart.

10. Employees feel we put our business goals ahead of the welfare of our

workers.

If you agree with more than one or two of the above statements, it is

unlikely that a new safety program can succeed without a safety culture change

dialogues, education and training.

1997 Rosa Antonia Carrillo 16

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Dangers of ReikiDocumento38 pagineThe Dangers of ReikiAnn Onimous100% (1)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Eckhardt TradingDocumento30 pagineEckhardt Tradingfredtag4393Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- TeachYourselfLatinBett PDFDocumento380 pagineTeachYourselfLatinBett PDFmeanna93% (14)

- History of Socialism - An Historical Comparative Study of Socialism, Communism, UtopiaDocumento1.009 pagineHistory of Socialism - An Historical Comparative Study of Socialism, Communism, UtopiaMaks imilijanNessuna valutazione finora

- ANA Code of EthicsDocumento2 pagineANA Code of EthicsPhil SimonNessuna valutazione finora

- Pe Lesson PlanDocumento5 paginePe Lesson Planapi-4386615930% (1)

- Second Chakra Pelvic Chakra Svadhisthana Chakra - My ChakrasDocumento3 pagineSecond Chakra Pelvic Chakra Svadhisthana Chakra - My ChakrasEsScents CandlesNessuna valutazione finora

- Pearls of Wisdom Kuthumi and The Brothers of The Golden Robe - An Exposé of False TeachingsDocumento20 paginePearls of Wisdom Kuthumi and The Brothers of The Golden Robe - An Exposé of False TeachingsCarolus Fluvius100% (1)

- The Chrysanthemums by John SteinbeckDocumento2 pagineThe Chrysanthemums by John SteinbeckAbdussalam100% (1)

- On Optimism and DespairDocumento3 pagineOn Optimism and DespairAmy Z100% (1)

- Ther AvadaDocumento8 pagineTher AvadakatnavNessuna valutazione finora

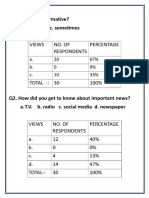

- Chapter 2Documento4 pagineChapter 2KaidāNessuna valutazione finora

- L2 Cpar W2Q1-2.1Documento41 pagineL2 Cpar W2Q1-2.1Angel Julao OliverNessuna valutazione finora

- Bab 1-5 - Revisi P1 - 2Documento119 pagineBab 1-5 - Revisi P1 - 2Melisa ParlinNessuna valutazione finora

- Material SelfDocumento8 pagineMaterial Selfmj rivera100% (3)

- Innovative Ideas For Chemical Engineering StudentsDocumento14 pagineInnovative Ideas For Chemical Engineering Studentsbalamurugan_pce20020% (1)

- 2 Perez v. CatindigDocumento5 pagine2 Perez v. Catindigshlm bNessuna valutazione finora

- 2.3 Load Combination's: NotationDocumento24 pagine2.3 Load Combination's: NotationAshmajit MandalNessuna valutazione finora

- KV Physics ImportantDocumento87 pagineKV Physics Importantpappu khanNessuna valutazione finora

- Congress MilitantDocumento128 pagineCongress MilitantGiovanni SavinoNessuna valutazione finora

- 爱在黎明破晓时 Before Sunrise 中英文剧本Documento116 pagine爱在黎明破晓时 Before Sunrise 中英文剧本yuhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Cindy Gomez-Schemp PostingDocumento5 pagineCindy Gomez-Schemp PostingRob PortNessuna valutazione finora

- International Business Chapter 2Documento7 pagineInternational Business Chapter 2DhavalNessuna valutazione finora

- Questions For Sociology ProjectDocumento14 pagineQuestions For Sociology ProjectSuyash TripathiNessuna valutazione finora

- Shanghan Lun: Zabing Lun (Simplified ChineseDocumento2 pagineShanghan Lun: Zabing Lun (Simplified ChineseDoktormin106Nessuna valutazione finora

- Group 10 Ge 6 ReportDocumento41 pagineGroup 10 Ge 6 ReportJonabel G. MontalboNessuna valutazione finora

- SS4291Documento7 pagineSS4291Alex ZhangNessuna valutazione finora

- Transfiguration of The World and of Life in Mysticism - Nicholas ArsenievDocumento9 pagineTransfiguration of The World and of Life in Mysticism - Nicholas ArsenievCaio Cardoso100% (1)

- The Basic Outline of A KhutbahDocumento4 pagineThe Basic Outline of A KhutbahhasupkNessuna valutazione finora

- Charles Bonnet SyndromDocumento6 pagineCharles Bonnet SyndromredredrobinredbreastNessuna valutazione finora