Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Death Looms Over Haiti

Caricato da

riddock0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

31 visualizzazioni1 paginaDeath Looms Over Haiti (Earthquake Disaster - Geographies of Natural Hazards) Straits Times Article

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoDeath Looms Over Haiti (Earthquake Disaster - Geographies of Natural Hazards) Straits Times Article

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

31 visualizzazioni1 paginaDeath Looms Over Haiti

Caricato da

riddockDeath Looms Over Haiti (Earthquake Disaster - Geographies of Natural Hazards) Straits Times Article

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 1

You see it in hot, dusty and desper-

ate slums like Carrefour, where the

damage caused by the magnitude 7.0

quake is slowly dissolving into the ur-

ban decay caused by decades of abject

poverty.

Some see the widespread destruc-

tion as an opportunity for a historic re-

birth. Haiti, after all, was once the rich-

est French colony in the Americas

thanks to its sugar, coffee and indigo

dye industries.

But I wonder instead if these are the

final days of a country on its deathbed.

I have never witnessed the death of

a nation, but I would imagine that it

looks something like the trauma Haiti

is going through.

The way Haitians and foreign aid

workers describe it, the recent earth-

quake that brought the country to its

knees may just be the opening act.

Many more crushing blows could

strike later this year.

For starters, heavy rain will pelt the

island in the coming weeks. When

the rains come, the streets are like the

sea. Theres water everywhere, said

my driver, Mr Gean Sonny Lafable, 35.

The rain is expected to loosen and

bring down whatever buildings the

earthquake failed to destroy. The wa-

ters would also accelerate the spread

of diseases among an already

shell-shocked population.

And if the hurricane season be-

tween June and November turns out to

be as destructive as the ones in recent

years, all current efforts to provide

Haitians with temporary shelter and

clean water would be for naught.

In the face of all this, Haiti has no

functioning government or central au-

thority beyond the veneer of control

imposed by the massive United States

military presence.

Ordinary Haitians say they expect a

two-year wait before an election can

be held to pick a new government

that is, if public anger over the incom-

petence of the surviving leaders does

not explode into street violence and an-

archy.

All the ingredients for violence are

piling up day after day, Mr Marc

Bazin, a former Haitian prime minister

and presidential candidate, told The

Straits Times.

The government seems to be

counting on the international commu-

nity to keep the people quiet. But they

are wrong because beyond a certain

point, there is nothing. People will

come looking for (the Haitian lead-

ers).

What happens then? Would there

be a revolution? Will Haiti turn on it-

self in one final act of destruction?

We have seen traces of civilisa-

tions that have perished, added Mr

Bazin.

So if civilisations could die, then a

country could die as well. Its a horri-

ble scenario, but weve got to integrate

that scenario into whats possible.

Existential crisis

HAITI has been held back from a total

collapse thus far by the massive injec-

tion of international aid and the pres-

ence of about 20,000 US troops.

Many, however, wonder how long this

effort can be sustained.

Even though President Barack

Obama has pledged to mobilise every

element of (US) national capacity to

help Haiti, it is lost on no one that he

is already waging two expensive wars

in Iraq and Afghanistan, and strug-

gling to contain runaway government

spending.

Yet, it is a problem from which Mr

Obama cannot walk away.

A total collapse in Haiti would

prompt refugees to flood the US.

More worryingly perhaps, it could

turn Haiti into the Yemen or Somalia

of the Caribbean, a safe haven for ter-

rorist groups right on the doorstep of

America.

Some, including ordinary Haitians

themselves, have suggested that Wash-

ington should go all the way and take

over Haiti entirely. There is a histori-

cal precedence, given that the US occu-

pied Haiti between 1915 and 1934.

Haiti needs a strongman now,

said Mr Peter Doceis, 55, a street ven-

dor. The US should just take over. If

not, maybe China or Russia. We are

not afraid.

The more likely outcome, I suspect,

is one where Haiti languishes in an ex-

istential limbo: neither strong enough

to stand on its own feet nor strategical-

ly important enough to be swallowed

up by a major power.

It is an ignominious fate for a na-

tion that in 1804 became the first Lat-

in American country to gain independ-

ence, and the first to do so from a suc-

cessful slave revolt.

Haiti never gets a chance, said

Mr Chad Snyder, 33, an American mis-

sionary whose family ties with Haiti go

back 40 years. Every time things are

about to look up, bam, they are hit

with some new trouble. I didnt think

things could get any worse, but here

we are.

The crossroads

DESPITE all the despondency, Mr Aar-

on Nelson, a Haitian chef and evange-

list, is not about to give up just yet.

He is hoping to tap into the outpour-

ing of international goodwill to help

build a better future for the weakest

lot in Haitian society: the orphans.

On an empty 1.2ha plot of land in ru-

ral Gressier, a two-hour drive west of

the capital Port-au-Prince, he hopes

to build an orphanage for 200 chil-

dren, and eventually a school for about

400 students.

I chose this place because I want

the children to be far away from all the

craziness in the city, Mr Nelson said

on Jan 24 when he brought me and two

volunteers from a Singapore relief mis-

sion to the site of his dreams.

This is where I hope they realise

their aspirations. Maybe one day, the

president of Haiti will come from

here.

Realising this vision will not come

cheap. He has paid US$38,000

(S$53,400) for the plot of land, but

would need another US$400,000 just

to build the orphanage.

The Singapore volunteers from

non-profit organisation CityCare said

they would study Mr Nelsons plans to

see if they could help raise funds. Giv-

en the millions of dollars in donations

being raised for Haiti around the clock,

Mr Nelson will have no shortage of al-

ternative venues for funds as well.

While no one doubts that the out-

pouring of global compassion can be

channelled for positive projects like

Mr Nelsons, there are concerns none-

theless that it would worsen the atti-

tude of dependence that is already

prevalent in Haitian society.

Said Mr Snyder, the American mis-

sionary: Over the years, people keep

giving food and money but they dont

teach the Haitians how to do things for

themselves.

Now that you have aid and money

pouring in on such a large scale, Im

not sure how you are going to reverse

that mindset.

On a broader level, there are also

questions about how the hundreds of

millions of dollars pledged to Haiti

would eventually be administered.

Would the elite exploit the situation

for their own gain? Can the poor and

those without a voice in the political

system get a fair share?

Mr Bazin, the Haitian politician

who is also a World Bank expert on de-

velopment issues, said the country

needs to convene a major conference

where all the key actors can get togeth-

er to resolve these issues.

Unless we Haitians can sit togeth-

er and agree on the minimum that has

to be done, to reflect better the social

fabric, the money we are getting from

the international community is going

to go nowhere, he added.

People should be made aware that

we are going down the drain. We need

to get on another path, a better path.

But who would provide the leader-

ship at this crucial hour? So far none

of Haitis economic or political elite,

safely ensconced in their expensive

houses high above the ruins of

Port-au-Prince, has stepped forward.

There is widespread talk of a reli-

gious revival in Haiti following the dev-

astating earthquake. Perhaps the

churches will emerge as a new force in

Haitian politics.

Half of Haitis 9.8 million popula-

tion is under 20 years old, so maybe a

charismatic young man or woman will

rise up and answer the call.

There are many questions in Haiti

today, but few, if any, good answers.

It is fitting then that I spent my

week-long trip in a slum named Carre-

four, which in French means cross-

roads.

This long-suffering country has nev-

er been at a more critical juncture.

chinhon@sph.com.sg

BY CHUA CHIN HON

US BUREAU CHIEF

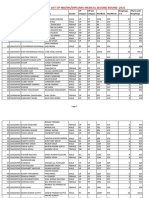

BRIEF HISTORY

Gained independence in 1804

after a successful slave revolt

against the French.

Oppressed by a long line of

dictators even after independence,

while repeated coups destabilised

the country further.

ECONOMY

The poorest country in the

Western hemisphere.

Economy shrank by 0.2 per cent

annually during the 1980s and by

0.4 per cent a year in the 1990s.

Has one of the highest rich-poor

gaps in the world. The richest

1 per cent own nearly half the

countrys wealth.

More than two-thirds of its

labour force do not have jobs.

POLITICS

Suffered 32 coups in its

200-year history.

The military was disbanded in

1994 to prevent further coups.

Remains unclear when the

country will be ready for fresh

elections.

POPULATION

Grew from five million to nine

million in recent decades despite a

shrinking economy.

Half the population is under the

age of 20, and illiterate.

Eight in 10 live in poverty.

HEALTH

More than half of Haitian

children are malnourished.

General population has limited

or no access to clean drinking

water.

About 5 per cent of adults

infected with HIV.

Source: World Bank, CIA World Factbook

Haiti has long been a tinderbox of socio-economic and

political tension. Some fear the recent earthquake might

ignite this explosive mix, and spark open violence and

anarchy. A quick glance at some key indicators:

2

/3 of labour force do not have a job

A labourer building a simple tomb in a cemetery on the outskirts of Port-au-Prince. A proper burial like this has become something of a luxury in

Haiti, given the massive death toll from the earthquake. Many bodies are being dumped into mass graves or remain buried under the rubble.

like a permanent haze. You smell

it in the air while walking past

collapsed buildings and houses,

under which dozens if not hun-

dreds of bodies remain buried

since the Jan 12 earthquake.

A child at the Notre Dame de la Nativite orphanage in Port-au-Prince last week. Generations of

Haitians will be shaped by how the country responds to this disaster. ST PHOTOS: CHUA CHIN HON

As Haiti tries to pick up the pieces after the devastating quake on

Jan 12, what lies ahead for the stricken Caribbean nation? A chance

for a historic rebirth or a country approaching its final days?

The Straits Times spent a week on the ground in Haiti.

Death looms

over Haiti

worldinternational

THE STRAITS TIMES MONDAY, FEBRUARY 1 2010 PAGE A14

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a DisasterDa EverandThe Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a DisasterValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (6)

- Fast DraftDocumento6 pagineFast Draftapi-240809165Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Never Ending Story: The Haitian Boat PeopleDocumento7 pagineThe Never Ending Story: The Haitian Boat PeopleJonRamosNessuna valutazione finora

- Force Démocratique Haitien Intégré: Open LetterDocumento2 pagineForce Démocratique Haitien Intégré: Open LetterDr Eddy delaleuNessuna valutazione finora

- AP - HaitiDocumento3 pagineAP - HaitiInterActionNessuna valutazione finora

- Zachary Mcginnis Fast Draft EditDocumento6 pagineZachary Mcginnis Fast Draft Editapi-241827589Nessuna valutazione finora

- Hallward, 'Haiti 2010, Exploiting Disaster'Documento28 pagineHallward, 'Haiti 2010, Exploiting Disaster'acountrydoctorNessuna valutazione finora

- How Human Rights Can Build Haiti: Activists, Lawyers, and the Grassroots CampaignDa EverandHow Human Rights Can Build Haiti: Activists, Lawyers, and the Grassroots CampaignNessuna valutazione finora

- Dream Builders, Dream Killers: Voice of an Immigrant from HaitiDa EverandDream Builders, Dream Killers: Voice of an Immigrant from HaitiNessuna valutazione finora

- 2010-01-14 The Real Truth About Haiti and What Your Church Can Do Now and in The Future - FlourishDocumento3 pagine2010-01-14 The Real Truth About Haiti and What Your Church Can Do Now and in The Future - FlourishPlant With PurposeNessuna valutazione finora

- Unravelling Haiti: A Nation In Turmoil - Understanding the Roots of Gang Violence, Political Chaos, and the Humanitarian Crisis in 2024Da EverandUnravelling Haiti: A Nation In Turmoil - Understanding the Roots of Gang Violence, Political Chaos, and the Humanitarian Crisis in 2024Nessuna valutazione finora

- Informative Speech OutlineDocumento7 pagineInformative Speech Outlineapi-283865133Nessuna valutazione finora

- Haiti: Why The World's Disaster Relief Was A Failure and Why We're Choosing To Ignore ItDocumento10 pagineHaiti: Why The World's Disaster Relief Was A Failure and Why We're Choosing To Ignore ItAshley KingNessuna valutazione finora

- Haiti: Courage and Resilience of a Great NationDa EverandHaiti: Courage and Resilience of a Great NationNessuna valutazione finora

- Poverty, Vulnerability and Underdevelopment in HaitiDocumento2 paginePoverty, Vulnerability and Underdevelopment in HaitiThessalonica CañonNessuna valutazione finora

- Haiti 2 HighlightDocumento10 pagineHaiti 2 HighlightAshley KingNessuna valutazione finora

- Harvesting Haiti: Reflections on Unnatural DisastersDa EverandHarvesting Haiti: Reflections on Unnatural DisastersNessuna valutazione finora

- UN Mission To Haiti Is A Foreign Occupation, Repressing Haitian SovereigntyDocumento4 pagineUN Mission To Haiti Is A Foreign Occupation, Repressing Haitian SovereigntyAntonio UckmarNessuna valutazione finora

- Haiti Story ReconstructionDocumento3 pagineHaiti Story ReconstructionevleopoldNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is The Best Plan For Rebuilding Haiti, After The Earthquake of January 12, 2010?Documento4 pagineWhat Is The Best Plan For Rebuilding Haiti, After The Earthquake of January 12, 2010?Destin JeanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Dominican Republic and Haiti: One Island, Two Nations, Lots of TroubleDocumento3 pagineThe Dominican Republic and Haiti: One Island, Two Nations, Lots of TroubleMădălina-Elena GogotăNessuna valutazione finora

- Hurricane Matthew in Haiti EssayDocumento6 pagineHurricane Matthew in Haiti Essayapi-312444598Nessuna valutazione finora

- Research Paper Topics On HaitiDocumento4 pagineResearch Paper Topics On Haitifvjebmpk100% (1)

- Haiti Insurrection Military InterventionDocumento10 pagineHaiti Insurrection Military InterventionArthur MaximeNessuna valutazione finora

- Haiti Problem Tree Activity and ReflectionDocumento4 pagineHaiti Problem Tree Activity and Reflectionapi-681822646Nessuna valutazione finora

- Haiti Earthquake Literature ReviewDocumento4 pagineHaiti Earthquake Literature Reviewea219sww100% (1)

- Country Study On Haiti Spring 2012Documento42 pagineCountry Study On Haiti Spring 2012Pia FrascatoreNessuna valutazione finora

- Haiti's Natural & Cultural VulnerabilityDocumento12 pagineHaiti's Natural & Cultural VulnerabilityVanessaXiongNessuna valutazione finora

- The Golden Door: International Migration, Mexico, and the United StatesDa EverandThe Golden Door: International Migration, Mexico, and the United StatesNessuna valutazione finora

- Serve The People 09Documento40 pagineServe The People 09Mosi Ngozi (fka) james harrisNessuna valutazione finora

- Haiti'S Development Needs: HearingDocumento58 pagineHaiti'S Development Needs: HearingScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Haiti Research Paper TopicsDocumento7 pagineHaiti Research Paper Topicskhkmwrbnd100% (1)

- HaitiDocumento2 pagineHaitiTinaNessuna valutazione finora

- "Haiti" by Henry Louis Gates, Jr.Documento34 pagine"Haiti" by Henry Louis Gates, Jr.NYU Press100% (2)

- ExtemporaryanchorpieceDocumento3 pagineExtemporaryanchorpieceapi-283946433Nessuna valutazione finora

- Haiti Research PaperDocumento8 pagineHaiti Research Paperhbzqwpulg100% (1)

- The Diaspora: A Spiritual Journey of Two FriendsDa EverandThe Diaspora: A Spiritual Journey of Two FriendsNessuna valutazione finora

- The Root of Haiti's Misery Reparations To Enslavers - The New York TimesDocumento36 pagineThe Root of Haiti's Misery Reparations To Enslavers - The New York Timesclaudio petroNessuna valutazione finora

- Why Haiti Needs New Narratives: A Post-Quake ChronicleDa EverandWhy Haiti Needs New Narratives: A Post-Quake ChronicleNessuna valutazione finora

- Apocalypse The Girl Who CanDocumento8 pagineApocalypse The Girl Who CanClyde PasagueNessuna valutazione finora

- Haiti ProjectDocumento6 pagineHaiti ProjectmfresonkeNessuna valutazione finora

- Despite $1.2 Billion in Donations, Haiti Shows Scant Signs of RecoveryDocumento5 pagineDespite $1.2 Billion in Donations, Haiti Shows Scant Signs of RecoveryInterActionNessuna valutazione finora

- Roadmap to Haiti’S Next Revolution: Capitalizing Haiti’S Economy with Haitian Diaspora RemittancesDa EverandRoadmap to Haiti’S Next Revolution: Capitalizing Haiti’S Economy with Haitian Diaspora RemittancesNessuna valutazione finora

- ReportDocumento4 pagineReportapi-320496148Nessuna valutazione finora

- Senate Hearing, 111TH Congress - Haiti: From Rescue To Recovery and ReconstructionDocumento56 pagineSenate Hearing, 111TH Congress - Haiti: From Rescue To Recovery and ReconstructionScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Foreign AidDocumento2 pagineForeign AidInterActionNessuna valutazione finora

- Embargo Lifted Against Haiti Massive Foreign Aid Expected To FolDocumento4 pagineEmbargo Lifted Against Haiti Massive Foreign Aid Expected To FolAadarsh MittalNessuna valutazione finora

- Oxfam - Haiti - A Once in A Century Chance For Change - 2010 MarchDocumento20 pagineOxfam - Haiti - A Once in A Century Chance For Change - 2010 MarchInterActionNessuna valutazione finora

- Haiti: A Once-in-a-Century Chance For Change: Beyond Reconstruction: Re-Envisioning Haiti With Equity, Fairness, and OpportunityDocumento20 pagineHaiti: A Once-in-a-Century Chance For Change: Beyond Reconstruction: Re-Envisioning Haiti With Equity, Fairness, and OpportunityOxfamNessuna valutazione finora

- Haiti: A Once-in-a-Century Chance For Change: Beyond Reconstruction: Re-Envisioning Haiti With Equity, Fairness, and OpportunityDocumento20 pagineHaiti: A Once-in-a-Century Chance For Change: Beyond Reconstruction: Re-Envisioning Haiti With Equity, Fairness, and OpportunityOxfamNessuna valutazione finora

- Haiti: A Once-in-a-Century Chance For Change: Beyond Reconstruction: Re-Envisioning Haiti With Equity, Fairness, and OpportunityDocumento20 pagineHaiti: A Once-in-a-Century Chance For Change: Beyond Reconstruction: Re-Envisioning Haiti With Equity, Fairness, and OpportunityOxfamNessuna valutazione finora

- What disasters reveal about class & inequalityDocumento15 pagineWhat disasters reveal about class & inequalityLiamar DuránNessuna valutazione finora

- Apocalypse by Junot Diaz PDFDocumento12 pagineApocalypse by Junot Diaz PDFKaneki KenNessuna valutazione finora

- 3285257, 2pages - EditedDocumento4 pagine3285257, 2pages - EditedLinetNessuna valutazione finora

- Doing What We Can For Haiti, Cato Policy AnalysisDocumento8 pagineDoing What We Can For Haiti, Cato Policy AnalysisCato InstituteNessuna valutazione finora

- Travesty in Haiti: A true account of Christian missions, orphanages, fraud, food aid and drug traffickingDa EverandTravesty in Haiti: A true account of Christian missions, orphanages, fraud, food aid and drug traffickingValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5)

- Eyes of The HeartDocumento25 pagineEyes of The HeartDavideVitaliNessuna valutazione finora

- IRC Report HaitiAnniversaryDocumento22 pagineIRC Report HaitiAnniversaryInterActionNessuna valutazione finora

- TW 20110108Documento10 pagineTW 20110108waqar2010Nessuna valutazione finora

- Who Owns HaitiDocumento208 pagineWho Owns HaitiLeoCutrix100% (2)

- Understanding Risk in An Evolving World - Policy NoteDocumento16 pagineUnderstanding Risk in An Evolving World - Policy NoteriddockNessuna valutazione finora

- TruthsDocumento3 pagineTruthsKelvin WongNessuna valutazione finora

- Globalisation of ServicesDocumento15 pagineGlobalisation of Servicesriddock100% (1)

- China at A Crossroads (2012)Documento14 pagineChina at A Crossroads (2012)riddockNessuna valutazione finora

- A Theory of Everything (Globalization & IT)Documento3 pagineA Theory of Everything (Globalization & IT)riddockNessuna valutazione finora

- Atlas of Global Development (1st Edition)Documento146 pagineAtlas of Global Development (1st Edition)riddock100% (1)

- Poverty PDFDocumento12 paginePoverty PDFriddock100% (1)

- Trigger Activity (Linkages) Uniforms To Cost More As Cotton Prices SoarDocumento1 paginaTrigger Activity (Linkages) Uniforms To Cost More As Cotton Prices SoarriddockNessuna valutazione finora

- A+ For International School EducationDocumento1 paginaA+ For International School EducationriddockNessuna valutazione finora

- Geoscience Australia - Map Reading GuideDocumento18 pagineGeoscience Australia - Map Reading Guiderossd1969Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Singapore For SingaporeansDocumento1 paginaA Singapore For SingaporeansriddockNessuna valutazione finora

- Cultural Geography and Place-Based Problem SolvingDocumento8 pagineCultural Geography and Place-Based Problem SolvingriddockNessuna valutazione finora

- Fukuyama's Latest Nonsense and Why Karl Marx Was RightDocumento7 pagineFukuyama's Latest Nonsense and Why Karl Marx Was RightriddockNessuna valutazione finora

- Trigger Activity (Linkages) Red-Hot Demand For SpicesDocumento1 paginaTrigger Activity (Linkages) Red-Hot Demand For SpicesriddockNessuna valutazione finora

- A City in Flux - Documenting Berlin's Forgotten SpacesDocumento2 pagineA City in Flux - Documenting Berlin's Forgotten SpacesriddockNessuna valutazione finora

- Bright Students Can't Write EssaysDocumento3 pagineBright Students Can't Write EssaysriddockNessuna valutazione finora

- Executive SummaryDocumento16 pagineExecutive SummaryspiritualbeingNessuna valutazione finora

- Geographical InquiryDocumento4 pagineGeographical InquiryriddockNessuna valutazione finora

- Using Formative Assessment Rubrics For Professional Reflection On PracticeDocumento44 pagineUsing Formative Assessment Rubrics For Professional Reflection On PracticeriddockNessuna valutazione finora

- Geographic Perspective For Educators (National Geographic)Documento15 pagineGeographic Perspective For Educators (National Geographic)riddockNessuna valutazione finora

- GA GeographySummer2011SampleDocumento60 pagineGA GeographySummer2011SampleriddockNessuna valutazione finora

- Values Education and Human Rights: The Living Values Educational ProgrammeDocumento10 pagineValues Education and Human Rights: The Living Values Educational ProgrammeAijaz Haider HussainiNessuna valutazione finora

- Tomorrow's CitizensDocumento5 pagineTomorrow's CitizensriddockNessuna valutazione finora

- Constructing A Coherent Curriculum For GeographyDocumento17 pagineConstructing A Coherent Curriculum For GeographyriddockNessuna valutazione finora

- The Place of Imagination in GeographyDocumento18 pagineThe Place of Imagination in Geographyriddock100% (1)

- Goals of Sustainable DevelopmentDocumento1 paginaGoals of Sustainable DevelopmentriddockNessuna valutazione finora

- Singapore in Figures 2012Documento31 pagineSingapore in Figures 2012riddockNessuna valutazione finora

- Educating For Intellectual VirtuesDocumento1 paginaEducating For Intellectual VirtuesriddockNessuna valutazione finora

- Artful Thinking (Final Report) PresentationDocumento50 pagineArtful Thinking (Final Report) Presentationriddock100% (2)

- Waves of Feminism and The MediaDocumento16 pagineWaves of Feminism and The MediaYasir HamidNessuna valutazione finora

- National ARtistDocumento6 pagineNational ARtistFrancis DacutananNessuna valutazione finora

- Test Bank For Economic Development The Pearson Series in Economics, 11th Edition, Michael P Todaro, ISBN-10: 0138013888, ISBN-13: 9780138013882Documento36 pagineTest Bank For Economic Development The Pearson Series in Economics, 11th Edition, Michael P Todaro, ISBN-10: 0138013888, ISBN-13: 9780138013882zirconic.dzeron.8oyy100% (13)

- EIIB Employees Challenge Deactivation OrderDocumento7 pagineEIIB Employees Challenge Deactivation OrderjannahNessuna valutazione finora

- Beyond The Diaspora - A Response To Rogers BrubakerDocumento13 pagineBeyond The Diaspora - A Response To Rogers BrubakerLa IseNessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento2 pagineUntitledmar wiahNessuna valutazione finora

- Global DemocracyDocumento42 pagineGlobal DemocracyAlex MárquezNessuna valutazione finora

- UP MDMS Merit List 2021 Round2Documento168 pagineUP MDMS Merit List 2021 Round2AarshNessuna valutazione finora

- Historical Background of IndonesiaDocumento4 pagineHistorical Background of IndonesiaTechno gamerNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Teachings of The Church: Rights and ResponsibilitiesDocumento23 pagineSocial Teachings of The Church: Rights and ResponsibilitiesKê MilanNessuna valutazione finora

- Request FormDocumento8 pagineRequest FormOlitoquit Ana MarieNessuna valutazione finora

- Republic Vs Glasgow GR 170281Documento2 pagineRepublic Vs Glasgow GR 170281Artfel LazoNessuna valutazione finora

- Henley Headmaster's 1940 - DiaryDocumento43 pagineHenley Headmaster's 1940 - DiaryHilary John BarnesNessuna valutazione finora

- American Stories A History of The United States Combined Volume 1 and 2 1st Edition Brands Solutions ManualDocumento24 pagineAmerican Stories A History of The United States Combined Volume 1 and 2 1st Edition Brands Solutions ManualMichaelKimkqjp100% (49)

- Friedan's The Feminine MystiqueDocumento21 pagineFriedan's The Feminine Mystiquedorkery100% (7)

- Deconstruction of El FilibusterismoDocumento2 pagineDeconstruction of El FilibusterismoPanergo ErickajoyNessuna valutazione finora

- Study of Fumihiko Maki and Group FormDocumento14 pagineStudy of Fumihiko Maki and Group FormJinting LeeNessuna valutazione finora

- Government Accounting Written ReportDocumento14 pagineGovernment Accounting Written ReportMary Joy DomantayNessuna valutazione finora

- Independence and Partition (1935-1947)Documento3 pagineIndependence and Partition (1935-1947)puneya sachdevaNessuna valutazione finora

- Analisa BEADocumento20 pagineAnalisa BEATest AccountNessuna valutazione finora

- Notes: Introduction: Anthony Giddens - Social Theory and PoliticsDocumento46 pagineNotes: Introduction: Anthony Giddens - Social Theory and Politics01,CE-11th Tasneem Ahmed ShuvoNessuna valutazione finora

- Global Traffic Technologies v. STCDocumento7 pagineGlobal Traffic Technologies v. STCPriorSmartNessuna valutazione finora

- I. Concepts and Definitions I. Concepts and DefinitionsDocumento64 pagineI. Concepts and Definitions I. Concepts and DefinitionsAmbrose KessyNessuna valutazione finora

- (1863) The Record of Honourable Clement Laird Vallandigham On Abolition, The Union, and The Civil WarDocumento262 pagine(1863) The Record of Honourable Clement Laird Vallandigham On Abolition, The Union, and The Civil WarHerbert Hillary Booker 2nd100% (1)

- Memorandum FOR: Provincial Director: Mountain Province Provincial Police OfficeDocumento12 pagineMemorandum FOR: Provincial Director: Mountain Province Provincial Police OfficePnpMountain Province PcaduNessuna valutazione finora

- Response To Rep. Jamaal Bowman's Withdrawal of Support For The Israel Relations Normalization ActDocumento3 pagineResponse To Rep. Jamaal Bowman's Withdrawal of Support For The Israel Relations Normalization ActJacob KornbluhNessuna valutazione finora

- Civil Rights Movement Lesson PlanDocumento3 pagineCivil Rights Movement Lesson Planapi-210565804Nessuna valutazione finora

- Music Role in South AfricaDocumento23 pagineMusic Role in South AfricaAdolph William HarryNessuna valutazione finora

- Cooperation and Reconstruction (1944-71) : Related LinksDocumento22 pagineCooperation and Reconstruction (1944-71) : Related Linkslb2111Nessuna valutazione finora

- M.A (Pol Science) Scheme of StudyDocumento2 pagineM.A (Pol Science) Scheme of StudyahsanNessuna valutazione finora