Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Pistachio-New Possibility

Caricato da

Fidanka Trajkova0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

15 visualizzazioni15 paginePistachio-new Possibility

Titolo originale

Pistachio-new Possibility

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoPistachio-new Possibility

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

15 visualizzazioni15 paginePistachio-New Possibility

Caricato da

Fidanka TrajkovaPistachio-new Possibility

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 15

PISTACHIO A NEW POSSIBILITY

VASKO ZLATKOVSKI, FIDANKA

TRAJKOVA, SASHA MITREV

Introduction

Fruit production in the Republic of Macedonia is mainly concentrated

in areas about 300 to 800 m above sea level, mostly in the western part of

the country. Due to different altitudes, there are various microclimate areas

with special weather conditions suitable for fruit production. Over 150,000

t of fruit are produced on an area of about 15,000 ha on some 7.6 million

fruit trees, about half of which are apple trees (Agency for Foreign

Investment of the Republic of Macedonia, 2007).

One of the hardest declining is recorded in pear production which

suffered serious losses in the early 90s of the XX-th century, as a result of

the appearance of Fire blight (Erwinia amylovora (Burrill) Winslow et al.)

which devastated pear production in the eastern part of the Republic of

Macedonia, thus forcing fruit growers to seek other production

possibilities. Looking for a way out producers turned to other fruits thus

changing the fruit production structure by expanding fruits that were not

previously present in certain regions (Mitrev, 1994; Mitrev, 1995).

One of the fruits that draws the attention of fruit growers in the

Republic of Macedonia for sure is pistachio, as this fruit has the potential

to sustain all the challenges of different climate types. This fruit is quite

unknown to the broad audience but experiences from countries such as

Turkey give reason to a conclusion that it could prove itself worthy of trial

to be introduced. It is a nut fruit which is grown with great success in areas

with sub-tropic and moderate-continental climate type. The Republic of

Macedonia fits in both climate types and the possibilities for successful

large scale introduction are proven with the existence of the autochthonous

variety Pistacia terebintus L. that has been proven to be very resistant to

low temperatures and could be used as a root-stock (Petkov, 2002).

Due to the low content of fat and high content of proteins, carbon-

hydrates, minerals, vitamins and other bio-active materials pistachio is one

of the finest and most delicious nut-fruit with high nutritional and dietary

value. Pistachios nut contains 47-56% fat, 17.4-24% proteins, 4-19%

carbohydrates, 4-6.5% cellulose, 2.5-3% ash, and significant amounts of

vitamins A, B

1

(Petkov, 2002).

In spite of the fact that pistachio as a fruit is known for millennia its

globalization was initiated in the 60s of the XX century. Such interest is

due to the enormous demand on the market and its stable price. Although

it can be found on all continents, majority of orchards are located in the

Near East and Mid Asia. In 2000 there were 371,714 ha under pistachio

with the annual production of 430,313 t. Top countries holding majority of

the world production are Iran, Turkey, USA, Tunisia and Syria

respectively (Petkov, 2002).

Status presens

The average size of farming agricultural households producing fruit is

2.9 ha of the nations arable land and it has a declining trend from 21,500

ha in 1992 to 16,000 ha in 2003. Two thirds of the fruit producers are part-

time farmers. Between June and October, around 85% of the fruit

producers market their products, corresponding to the lowest market prices

(AgBiz Program, 2009; Petkov, 2002; Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry

and Water Economy of Republic of Macedonia, 2004; Ministry of

Agriculture, Forestry and Water Economy of The Republic of Macedonia,

2005).

Yields in qualitative and quantitative terms are low due to the use of

old machinery, uncertified propagating material and insufficient use of

agricultural inputs and irrigation. Fruit farmers are poorly organized. A

survey conducted among producers in 2005, wholesalers and retail traders

and agricultural associations showed that the fruit farming sector is

inadequately supported in financial and technical terms

(research/extension), as there is lack of packing, sorting and manipulation,

storage and processing capacities, and lack of relevant information on

market standards for quality for both domestic and foreign markets (AgBiz

Program, 2009).

In 2005, fruit export (including dried and semi processed) reached

18.4 million (mainly apples 30%, table grape 22%, wine grape 19% and

semi-processed fruit 8%), while fruit import was 15.6 million (85%

tropical fruits and citrus). Net exports were 2.8 million. The largest part

of the fruit export is with the neighboring countries (AgBiz Program,

2009).

Table 1. Crop area (ha) (State Statistic Office, Republic of Macedonia, Statistical

Data Base, 20.12.2010).

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005

Apples 7379 7456 7283 8110 8051 7200

Plums 3206 3655 3063 6141 6133 2610

Peaches 1411 1249 1320 1329 984 949

Apricots 597 433 424 368 350 345

Pears 1071 1099 1080 1039 1040 830

Cherries 360 360 358 345 354 300

Sour cherries 2270 2503 2518 2478 2492 1535

The Table 1 clearly identifies the constant fall in the area under

orchards on national level. Only apple orchards tend to keep some kind of

stability as the rest of the fruit records only downward trends.

In the last several years different factors determined the production

abilities; among many of them is the effect of climate change. In 2008

under the auspices of the Global Environmental Facility and UNDP a

Second National Communication on Climate Change was issued. A

number of academics and other relevant authorities worked to determine

what the Republic of Macedonia would be facing in the second and third

decade of the XXI century.

Many studies were carried out in order to provide answers to numerous

questions which were bothering Macedonian farmers, beginning from

ordinary disease appearance to such complex issues as climate change

effect, on which none of the farmers can have any influence to improve

production conditions. This paper deals with the effect of climate change

on the whole territory of the Republic of Macedonia (Ministry of

Environment and Physical Planning of Republic of Macedonia, 2008).

Weather conditions - National characteristics

Weather conditions are one of the most influential factors in

agriculture since there is no way to limit or prevent their influence over

any plant. Hence, proper research activities are essential in order to

determine whether any new crop (pistachio included) could adapt to the

standing conditions. Pistachio is a fruit which does not have great water

demand, so looking at the wider picture it is clear that it could serve as a

new opportunity in the areas with precipitation between 400 500 mm,

and that is the area that suffered most from the loss of pear orchard during

early 90s of the XX century. The precipitation distribution is quite

unfavorable for most of it comes in the months of February, March, May

and November, providing very little rainfall in the summer months

(Mitrev, Zlatkovski , 2010).

Figure 1. Precipitation layout (mm) in the Republic of Macedonia.

The picture clearly suggests the areas suitable for pistachio growing as

this crop is quite susceptible to hard and moist retaining soil types, since

there is significant level of jeopardy that the root system will suffer from

soil borne pathogens such are Verticillium sp., Alternaria sp., Phytophtora

sp., Armillaria sp. etc. (Petkov, 2002).

The other determination factor is the temperature and as presented in

Figure 2, the majority of the territory of the Republic of Macedonia is

exposed to higher average temperatures (above 14C). This is quite

important because as a heliophyte pistachio demands long, dry and hot

summers. Insufficient light leads to nut disability to reach optimum size

and that prevents the endocarp to detach (it does not break) (Petkov,

2002).

Figure 2. Average annual temperatures (C) in the Republic of Macedonia.

According to Petkov (2002), this factor presents no threat to pistachio

introduction since many research activities prove this crop as quite

resistant to this factor. Furthermore, having a late blooming period it is

very favorable in the areas that tend to have late spring frost, often causing

damages to apricot, peaches and almonds.

The rate of split nuts of some varieties is quite important. The bigger

the percentage of unsplit rate, the more unfavorable the variety is, since

there is a necessity for additional resources to open the unsplit nuts (Table

2). Generally, Iranian varieties have higher splitting rate (Ak, 1998)

Table 2. Rates of split nuts (%) (Ak, 1998).

Varieties Years Average

1992 1993 1994

Kirmizi 57.98 31.37 42.10 43.82

b

Siirt 79.49 64.69 55.29 66.49

a

Ohadi 76.56 41.96 22.52 47.01

b

Bilgen 75.01 36.93 13.72 41.89

b

Vahidi 38.46 55.53 3.22 32.40

c

Mumtaz 82.79 57.95 32.22 57.65

a

Average 68.38

a

48.07

b

28.18

c

48.21

LSD5% (variety): 0.17; LSD5% (year): 0.12; LSD5% (variety x year):

0.29;

Abcd: values marked with different letters are significantly different

Next on the level of importance for pistachio fruit are fruit weight, fat

and protein content. Such research was carried out on the nuts grown in

the collection garden of the Institute in Gaziantep. Eight of them were

Turkish (Kirmizi, Uzun, Halebi, Siirt, akmak, Ketengmlegi, Degirmi,

Sultani) and five of them were Iranian (Ohadi, Vahidi, Mmtaz, Haci

Serifi, Sefidi) ( Karaca, Nizamoglu, 1994).

The analyses were based on the results of 1984, 1985, 1987. The nuts

of Iranian pistachio trees were bigger than Turkish nuts. Approximate

weight of the 100 Iranian pistachio nuts was 162.03 g. while Turkish types

were about 129.72 g. splitting percentages of Turkish types were 67.14 %

and the Iranian nuts were about 78.70 %. Karaca and Nizamoglu (1994)

reported approximate fat of Turkish and Iranian nuts were about 57.68 %

and 55.43 %, respectively. The protein content of Turkish type was 22.08

% and for Iranian type it was 22.69 %. There was not an important

difference in protein content between Iranian and Turkish nuts.

Vulnerability and adaptation to climate change

The scenario used to determine possible outcomes is based onthe status

in the year 2006, performed on a comparative analysis of two thirty-year

series, i.e.1961-1990 and 1971-2000. The first analysis pointed out that the

period 1971-2000 was annually warmer than the period 1961-1990 in

almost all climate areas in the country, while mean monthly temperatures

varied during the year. Winter and summer months were warmer in

comparison to the period 1961-1990. Despite this, autumn and summer

months were colder compared to the previous thirty-year period. The

highest values of mean annual deviations of the air temperature in the

Republic of Macedonia appear in the region with sub-Mediterranean

climate (Valandovo 0.7 C, Gevgelija 0.5 C, and Nov Dojran 0.2 C).

Climate change projections of the main climate elements (temperature and

precipitation) have been made up to the year 2100 (Table 3), i.e. for the

periods 1996-2025, 2021-2050, 2050-2075, and 2071-2100 in comparison

with 1961- 1990.

According to the results presented in Table 3, the average increase of

temperature is between 1.0C by 2025, 1.9C by 2050, 2.9C by 2075, and

3.8C by 2100, while the average decrease of precipitation ranges from

3% in 2025, -5% in 2050, -8% in 2075, to -13% in 2100 in comparison

tothe reference period.

Table 3. Projected changes of average daily air temperature (C) and

precipitation for the Republic of Macedonia based on direct GCM output

interpolated into geographic location 21.5E and 41.5N with regard to the

period 1990 (Ministry of Environment and Physical Planning of Republic of

Macedonia, 2008).

Changes of temperature (C) Changes of precipitation (%)

ANNUAL ANNUAL

Sensitivity 2025 2050 2075 2100 2025 2050 2075 2100

Low 0.9 1.6 2.2 2.7 -1 -2 -4 -5

Mean 1 1.9 2.9 3.8 -3 -5 -8 -13

High 1.1 2.1 3.6 5.4 -6 -7 -12 -21

It is expected that the largest increase of air temperature in the

Republic of Macedonia is expected in the summer season, associated with

a strong decrease in precipitation as presented in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 4. Projected changes in average daily air temperature (C) based on direct GCM output (Ministry of Environment and

Physical Planning of Republic of Macedonia, 2008).

Average temperature change (C)

winter spring summer autumn

2025 2050 2075 2100 2025 2050 2075 2100 2025 2050 2075 2100 2025 2050 2075 2100

Low 0.7 1.4 1.8 2.2 0.7 1.3 1.8 2.2 1.2 2.2 3.2 3.7 0.8 1.5 2.2 2.6

Mean 0.8 1.7 2.3 3.0 0.8 1.5 2.2 3.2 1.4 2.5 4.1 5.4 0.9 1.7 2.8 3.7

High 0.9 1.9 2.9 4.2 0.9 1.8 2.9 4.6 1.7 2.9 5.1 7.6 1.1 2.0 3.6 5.3

Table 5. Projected changes in precipitation (%) based on direct GCM output (Ministry of Environment and Physical

Planning of the Republic of Macedonia, 2008).

Precipitation change (%)

winter spring summer autumn

2025 2050 2075 2100 2025 2050 2075 2100 2025 2050 2075 2100 2025 2050 2075 2100

Low 1 5 3 4 -3 -2 -7 -5 2 -16 -21 -21 2 -2 0 -5

Mean 0 1 2 -1 -5 -6 -10 -13 -7 -17 -27 -37 -1 -4 -9 -13

High -2 -1 1 -3 -7 -10 -13 -22 -24 -18 -33 -53 -3 -7 -17 -23

For the eastern part of Macedonia with prevailing continental climate

an impact of a slight increase in precipitation by 6%, is expected in winter,

but a decrease in all other seasons, most intensive (-20%) in summer. In

summer as well as in autumn, an increase in daily air temperature is

expected, reaching the maximum value of 5.2C in summer 2100.

Analysis of the impact in agriculture

General conclusion by the given data leads to the finding that there will

be significant decrease in yield, especially in vulnerable areas. By 2050,

Shtip as a city located in one of the most vulnerable areas and where

winter wheat is a major crop, is estimated to suffer yield loss of up to 17%

and grape yield in the region of Kavadarci by 2050 is estimated to reach

50%. The projections are made with the assumptions that crops will be

grown without the possibility to irrigate (Ministry of Environment and

Physical Planning of Republic of Macedonia, 2008).

In order to avoid greater negative effects it is suggested to implement

several adaptation measures, such asintroducing water-saving irrigation

measures, soil and water preservation, new agricultural practices,

introduction of less-water demanding crops (Ministry of Environment and

Physical Planning of Republic of Macedonia, 2008).

Due to climate change soil erosion is also expected to be accelerated.

The most vulnerable regions of cultivated soil are: Central Povardarie,

especially the area of the confluence of the rivers Crna and Bregalnica

with Vardar and South Povardarie (Ministry of Environment and Physical

Planning of Republic of Macedonia, 2008).

Results and discussion

Facing evident change in climate, recording a drop in areas planted

with orchards, which results with reduced production volume hence

increasing trading deficit, it is very important to set a course to intercept

the forthcoming changes and challenges.

Agriculture is determined by many factors and one of the most

influential is the natural one, hence the importance of carefully analyzing

every scenario that might appear in order to build-up a successful business.

As unpredictable as the market trends can be, and already manifesting

climate changes in many areas accompanied with a downward trend in

orchard area, it is a moment to set a direction in which Macedonian fruit

growers will identify their future activities. Knowing that fruit growing is

a long-term investment often with high demand for initial capital values, it

is of great importance to provide reliable information.

Pistachio is a typical xerophyte and its most favorable conditions are

those similar to arid, semi-desert and desert conditions of Near and Middle

East. Nedev et al. (1983) and Popov (1979) stated that pistachio roots were

found at a depth of 1.2 m in the first year of planting, while the depth of

pistachio roots at matured trees had reached 20 m. It is a fruit that

demands long, hot and dry summers but short and moderately cold

winters. Kaska et al. (1990) point out that in South Anatolia there is a

sufficient number of high summer temperatures and that there are 98-110

days with an average daily temperature above 30C. In areas where the

average daily temperature is below 22C, pistachio fruits do not mature,

the nut does not fill the shell, the percentage of opened fruits is low and

the mesocarp detaches from the endocarp with difficulties.

On the other hand, the need of pistachio for temperatures below 7C

represents a burden for successful introduction to the south. According to

the need for a number of hours with temperatures below 7C IPGRI

(1997) divided pistachio varieties into three groups:

- Low need (under 600C)

- Medium need (600-1200C)

- High need (above 1200C).

Knowing that almond and pistachio originate from the same area

(Mediterranean) their resistance to low temperatures is almost the same.

The difference is almonds earlier blooming period which makes that fruit

more susceptible to spring frosts as opposed to pistachio which blooms

much later. Furthermore, pistachio has a stable winter dorm period and

possible frequent changes of temperatures in the atmosphere will not cause

premature bud growth hence preventing any damage by spring frosts as

would be the case with almond (Petkov, 2002)

The weather in the regions suitable for pistachio growing in the

Republic of Macedonia varies from moderate continental to sub-

Mediterranean. Most northern city Kumanovo has annual average

temperature of 11.8C, Skopje 12C, Vinitsa 12.9C, Shtip 13.2C, Veles

13.3C, followed by Kochani 14.1C, Valandovo, Gjevgjelija and Dojran

with 14.2C, respectively. For pistachio it is of great importance to have a

high value of annual temperature sum because in insufficient values the

plant cannot complete the physiological process with a possibility to enter

winter unprepared. Highest temperature sums are recorded in the South

Povardarie region, in the cities Valandovo with annual temperature sum of

5210C, Gjevgjelija 5201C up to the northern city of Kumanovo with

sum of 4310C. In order for the fruit to ripen it is essential to have a sum

of active temperature above 10C, hence it should be avoided for planting

in regions where summers are not warm enough because fruits will not

ripen. Cities with highest active temperatures are Gjevgjelija 4446C,

Valandovo 4448C, Dojran 4403C, Kavadarci 4293C and Kumanovo

3662C respectively. Even though pistachio survives in quite arid areas, it

reacts quite positively to rainfall (Petkov, 2002; Mitrev, Zlatkovski, 2010).

Further fruit production in the Republic of Macedonia could consider

introducing pistachio in its strategies for development. If predictions of the

National communication on climate change are to be true, further drop in

yields in major growing areas will become a serious threat, especially to

cherry, sour cherry, apple and grape growing practices.

Data on weather, soil and existence of pistachio varieties point that

the growing this crop is quite possible, but a lot is yet to be done. Since

there is no plant propagation facility in the Republic of Macedonia and no

National list of approved varieties, it is essential to performcareful

research activities in order to set most adequate varieties in most suitable

regions. On the other hand, since areas in which pistachio would be

established do not have possibilities for irrigation, or such possibility

would require significant investment, setting proper planting dimension is

of great importance.

The next issue would be the establishment of new orchards. Proper

choice of rootstock is of great importance, as there are different varieties

resistant or susceptible to drought. Knowing various practices such as

planting rootstocks and later grafting use of 2-year old plantlets, it is quite

important to set adequate planting dimensions in order to use intercrops

for planting different crops which could support farms economic balance

(Petkov, 2002).

Conclusions

It is evident that even at this phase there are favorable conditions for

growing pistachio in several of the regions in the Republic of Macedonia.

Temperature sum is at the required level, precipitation level is enough to

sustain plants water needs and soil conditions are on the satisfactory side

as well.

Still, there are several important things that require attention, to set a

proper order of activities:

- Establishing scientific relations with institutions that have a tradition in

similar activities for staff and knowledge exchange

- Research of soil conditions (micro, macro nutrient, organic matter etc.)

- Establishment of a committee which would agree on a National variety

list

- Support to institutions that would initiate propagation production in the

Republic of Macedonia

- Due to frequent spring frost losses on almond, pistachio could be

considered a crop to replace orchards which are set for renovation

- Educate advisory staff on pistachios requirements, as the advisory

service is the one that has the capacity to respond to farmers needs at

lowest cost

- Set trial orchards, where training and research processes will take

place.

(e) Pistachio New Opportunity

(f) BSc, Krste Misirkov bb, p.o.box 201, Shtip 2000, Republic of

Macedonia, +389.32.390.700; +389.32.550.634

MSc, Krste Misirkov bb, p.o.box 201, Shtip 2000, Republic of Macedonia,

+389.32.390.700; +389.32.550.631

PhD, Krste Misirkov bb, p.o.box 201, Shtip 2000, Republic of Macedonia,

+389.32.390.700; +389.32.550.610

References

AgBiz Program (2009). The Apple Sector in Macedonia. USAID

Macedonia, pp.13

Agency for Foreign Investment of the Republic of Macedonia (2007).

Food Processing Industry, Investors Guide 2007, pp.10

Ak B. E. (1998). Fruit set and some fruit traits on Pistachio cultivars

grown under rainfed conditions at Caylanpinar State Farm. Cahiers

Options Mediterraneennes (CHIEAM),p. 217-223.

IPGRI (1997). Descriptors for Pistachio (Pistacia vera L.). International

Plant Genetic Resources Institute, Rome, Italy, pp.59.

Karaca R., Nizamoglu A. (1994). Quality characteristics of Turkish and

Iranian pistachio cultivars grown in Gaziantep. Acta Hort.

Kaska N., Ak B.E., Nikpeyma Y. (1990). Application of chip, patch and

spring-fall shield budding on different Pistacia species. In: Turkiye 1.

Antepfistigi Simpozyumu Bildirileri, 11-12 Eylul 1990, Gaziantep, 59-

67.

Ministry of Environment and Physical Planning of Republic of Macedonia

(2008). Second national communication on climate change, National

and University Library St. Kliment Ohridski, Skopje, Republic of

Macedonia, pp. 118.

Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Water Economy of Republic of

Macedonia (2005). Annual Agriculture Report 2004, Ministry of

Agriculture, Forestry and Water Economy, Unit for Analysis of

Agricultural Policy and Information, Skopje, Republic of Macedonia,

pp. 228,

. (2004). Annual Agriculture Report 2003, Ministry of Agriculture,

Forestry and Water Economy, Unit for Analysis of Agricultural Policy

and Information, Skopje, Republic of Macedonia, pp. 196

Mitrev S. and Zlatkovski V. (2010), Study on Sustainable Development of

Organic Agriculture in the East Planning Region, Goce Delchev

University, Shtip, Republic of Macedonia.

Mitrev S. (1995). Pathogenic and bacteriological characteristics of Erwinia

amylovora, the pathogen of pear and quince-trees in Macedonia. Plant

Protection, Vol. 46 (2), 212: 97-109.

.(1994). Fire blight of pear-trees in Macedonia. Yearbook for Plant

Protection, Vol. V, 59-70.

Nedev N., Serafimov S., Anadoliev G. (1983). Nut cultures. Hristo G.

Danov, Plovdiv, 273-290.

Petkov Gj. (2002). Ecological and biological characteristics of pistachio

(Pistacia vera L.) in Macedonia. Master thesis, University Ss. Cyril

and Methodius-Skopje, Faculty of Agriculture-Skopje, pp. 96.

Popov K.P. (1979). Fistashka v srednei Azii. Ylym, Ashkhabad, pp. 161.

State Statistic Office, Republic of Macedonia, Statistical Data Base

http://www.stat.gov.mk/pxweb2007bazi/Database/%D0%A1%D1%82

%D0%B0%D1%82%D0%B8%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B8%D0%BA

%D0%B0%20%D0%BF%D0%BE%20%D0%BE%D0%B1%D0%BB

%D0%B0%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B8/databasetree.asp, downloaded

on 20.12.2010

Appendix

Table 1. Crop area (ha) (State Statistic Office, Republic of Macedonia, Statistical

Data Base, 20.12.2010).

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005

Apples 7379 7456 7283 8110 8051 7200

Plums 3206 3655 3063 6141 6133 2610

Peaches 1411 1249 1320 1329 984 949

Apricots 597 433 424 368 350 345

Pears 1071 1099 1080 1039 1040 830

Cherries 360 360 358 345 354 300

Sour cherries 2270 2503 2518 2478 2492 1535

Table 2. Rates of split nuts (%) (Ak, 1998).

Varieties Years Average

1992 1993 1994

Kirmizi 57.98 31.37 42.10 43.82

b

Siirt 79.49 64.69 55.29 66.49

a

Ohadi 76.56 41.96 22.52 47.01

b

Bilgen 75.01 36.93 13.72 41.89

b

Vahidi 38.46 55.53 3.22 32.40

c

Mumtaz 82.79 57.95 32.22 57.65

a

Average 68.38

a

48.07

b

28.18

c

48.21

Table 3. Projected changes of average daily air temperature (C)

and precipitation for the Republic of Macedonia based on direct GCM output

interpolated into geographic location 21.5E and 41.5N with regards to the

period 1990 (Ministry of Environment and Physical Planning of the Republic

of Macedonia, 2008).

Changes of temperature (C) Changes of precipitation (%)

ANNUAL ANNUAL

Sensitivity 2025 2050 2075 2100 2025 2050 2075 2100

Low 0.9 1.6 2.2 2.7 -1 -2 -4 -5

Mean 1 1.9 2.9 3.8 -3 -5 -8 -13

High 1.1 2.1 3.6 5.4 -6 -7 -12 -21

Table 4. Projected changes in average daily air temperature (C) based on direct GCM output (Ministry of Environment and

Physical Planning of the Republic of Macedonia, 2008).

Average temperature change (C)

winter spring summer autumn

2025 2050 2075 2100 2025 2050 2075 2100 2025 2050 2075 2100 2025 2050 2075 2100

Low 0.7 1.4 1.8 2.2 0.7 1.3 1.8 2.2 1.2 2.2 3.2 3.7 0.8 1.5 2.2 2.6

Mean 0.8 1.7 2.3 3.0 0.8 1.5 2.2 3.2 1.4 2.5 4.1 5.4 0.9 1.7 2.8 3.7

High 0.9 1.9 2.9 4.2 0.9 1.8 2.9 4.6 1.7 2.9 5.1 7.6 1.1 2.0 3.6 5.3

Table 5. Projected changes in precipitation (%) based on direct GCM output (Ministry of Environment and Physical

Planning of the Republic of Macedonia, 2008).

Precipitation change (%)

winter spring summer autumn

2025 2050 2075 2100 2025 2050 2075 2100 2025 2050 2075 2100 2025 2050 2075 2100

Low 1 5 3 4 -3 -2 -7 -5 2 -16 -21 -21 2 -2 0 -5

Mean 0 1 2 -1 -5 -6 -10 -13 -7 -17 -27 -37 -1 -4 -9 -13

High -2 -1 1 -3 -7 -10 -13 -22 -24 -18 -33 -53 -3 -7 -17 -23

Figure 1. Precipitation layout (mm) in the Republic of Macedonia

Figure 2. Average annual temperatures (C) in The Republic of Macedonia.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Method Statement (RC Slab)Documento3 pagineMethod Statement (RC Slab)group2sd131486% (7)

- Outlook 2Documento188 pagineOutlook 2Mafer Garces NeuhausNessuna valutazione finora

- Status of Vegetable Peroduction in EthiopiaDocumento5 pagineStatus of Vegetable Peroduction in Ethiopiabini1290% (10)

- Valve Material SpecificationDocumento397 pagineValve Material Specificationkaruna34680% (5)

- Intro To Psychological AssessmentDocumento7 pagineIntro To Psychological AssessmentKian La100% (1)

- Itc LimitedDocumento64 pagineItc Limitedjulee G0% (1)

- 2018 The State of the World’s Forests: Forest Pathways to Sustainable DevelopmentDa Everand2018 The State of the World’s Forests: Forest Pathways to Sustainable DevelopmentNessuna valutazione finora

- Compartment SyndromeDocumento14 pagineCompartment SyndromedokteraanNessuna valutazione finora

- Pigeon Disease - The Eight Most Common Health Problems in PigeonsDocumento2 paginePigeon Disease - The Eight Most Common Health Problems in Pigeonscc_lawrence100% (1)

- Proizvodne Karakteristike I Ekonomski Aspekti Proizvodnje DUNJEDocumento4 pagineProizvodne Karakteristike I Ekonomski Aspekti Proizvodnje DUNJENikola StamenkovskiNessuna valutazione finora

- AcarologiaDocumento21 pagineAcarologiaCleiton DomingosNessuna valutazione finora

- SeminarDocumento26 pagineSeminarMekoninn HylemariamNessuna valutazione finora

- Rjis 16 04Documento14 pagineRjis 16 04geo12345abNessuna valutazione finora

- Introducation 1.1. Back Ground of The StudyDocumento26 pagineIntroducation 1.1. Back Ground of The StudyMELESE LENCHANessuna valutazione finora

- Department of Plant Science: Graduate ProgramDocumento32 pagineDepartment of Plant Science: Graduate ProgramMehari TemesgenNessuna valutazione finora

- Full Fruit Lecture 01Documento315 pagineFull Fruit Lecture 01HulushumNessuna valutazione finora

- Turkish Ornamental Plants Sector in The European Union Screening ProcessDocumento16 pagineTurkish Ornamental Plants Sector in The European Union Screening ProcessEman MurtzaNessuna valutazione finora

- Status Report On Fruits and Vegetables Production PDFDocumento13 pagineStatus Report On Fruits and Vegetables Production PDFash ritNessuna valutazione finora

- Rainfall Variation: Implication On Cocoa Yield in Ondo State, NigeriaDocumento10 pagineRainfall Variation: Implication On Cocoa Yield in Ondo State, NigeriaAmerican International Journal of Agricultural StudiesNessuna valutazione finora

- Climate and Actors of Agriculture ProductionDocumento1 paginaClimate and Actors of Agriculture ProductionflorenciafrNessuna valutazione finora

- Edited Machiweni Friend Agric Main Low Yield in MaizeDocumento6 pagineEdited Machiweni Friend Agric Main Low Yield in MaizeMUTANO PHILLIMONNessuna valutazione finora

- Soil Collection and Preparation For Pot Experiments V.2: ShareDocumento15 pagineSoil Collection and Preparation For Pot Experiments V.2: ShareKrista Mae LiboNessuna valutazione finora

- Literature ReviewDocumento10 pagineLiterature ReviewTesema YohanisNessuna valutazione finora

- 8 - Golja - Dolenc - MarinkovicDocumento19 pagine8 - Golja - Dolenc - MarinkovicSanja DolenecNessuna valutazione finora

- Structure and Management of Traditional Agroforestry Vineyards in The High Valleys of Southern BoliviaDocumento12 pagineStructure and Management of Traditional Agroforestry Vineyards in The High Valleys of Southern BoliviaChristian GaryNessuna valutazione finora

- Potato ProductionDocumento18 paginePotato ProductionaddisalemNessuna valutazione finora

- WWW - Pse 200912 0004Documento8 pagineWWW - Pse 200912 0004shanjanasri098Nessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter One 1.1 Background of The StudyDocumento8 pagineChapter One 1.1 Background of The StudyjosefNessuna valutazione finora

- Integrated Production and Protection Under Protected Cultivation in The Mediterranean RegionDocumento21 pagineIntegrated Production and Protection Under Protected Cultivation in The Mediterranean RegionVictor Lauro Perez GarciaNessuna valutazione finora

- Abiotic StressDocumento19 pagineAbiotic Stressborbala bereckiNessuna valutazione finora

- Morocco Vs Spain AvocadoDocumento7 pagineMorocco Vs Spain Avocadohkartit10Nessuna valutazione finora

- Siner by BirukDocumento19 pagineSiner by BirukAmisalu NigusieNessuna valutazione finora

- Effect of Climate Change On Maize Production in NigeriaDocumento5 pagineEffect of Climate Change On Maize Production in NigeriaPremier Publishers100% (1)

- Soil Erosion and Smallholders ConservatiDocumento14 pagineSoil Erosion and Smallholders ConservatiAbdusalam IdirisNessuna valutazione finora

- Ilievski Et Al. - JAPS 2023 No1Documento4 pagineIlievski Et Al. - JAPS 2023 No1Biljana AtanasovaNessuna valutazione finora

- Land Abandonment - Revised.M MJD FormattedDocumento21 pagineLand Abandonment - Revised.M MJD FormattedSmriti SNessuna valutazione finora

- 2003 Rome KeerthisingheDocumento15 pagine2003 Rome KeerthisinghekishkeNessuna valutazione finora

- Economic Aspects of Dried Fruit Production by CombDocumento14 pagineEconomic Aspects of Dried Fruit Production by CombSara ShahbazNessuna valutazione finora

- 02 Chapter 2Documento31 pagine02 Chapter 2Abiodun KomolafeNessuna valutazione finora

- SorghumDocumento29 pagineSorghumEsubalew TesfaNessuna valutazione finora

- Policy Brief: KarapinarDocumento4 paginePolicy Brief: KarapinarmedesdesireNessuna valutazione finora

- Effects of Rice Production Systems On Perceived Soil Degradation in Ekiti StateDocumento10 pagineEffects of Rice Production Systems On Perceived Soil Degradation in Ekiti StateUtibe Tibz IkpembeNessuna valutazione finora

- South African Crop Farming and Climate Change - An Economic Assessment of ImpactsDocumento13 pagineSouth African Crop Farming and Climate Change - An Economic Assessment of ImpactsHasan TafsirNessuna valutazione finora

- Mitikuetal 2022Documento28 pagineMitikuetal 2022yonas ashenafiNessuna valutazione finora

- Ournal of Frican Conomies Olume Umber PPDocumento26 pagineOurnal of Frican Conomies Olume Umber PPsadiapkNessuna valutazione finora

- Final Term PaperDocumento11 pagineFinal Term PaperJerico MagnoNessuna valutazione finora

- Post-Harvest Practices and Loss Assessment in Tomato (SolanumDocumento18 paginePost-Harvest Practices and Loss Assessment in Tomato (SolanumMuhammad FarhanNessuna valutazione finora

- A Swot Analysis of Organic Dried FigDocumento9 pagineA Swot Analysis of Organic Dried FigЮлия УстименкоNessuna valutazione finora

- Impact of Climate Change On Agriculture: Empirical Evidence From Arid RegionDocumento7 pagineImpact of Climate Change On Agriculture: Empirical Evidence From Arid Regionnoreen rafiqNessuna valutazione finora

- Amevoin2021 Article FruitFlySurveillanceInTogoWest PDFDocumento16 pagineAmevoin2021 Article FruitFlySurveillanceInTogoWest PDFBabugi Ernesto Antonio ObraNessuna valutazione finora

- Community Led Potato Seed Production - Eritrea ReportDocumento23 pagineCommunity Led Potato Seed Production - Eritrea ReportTesfaNewsNessuna valutazione finora

- Review 1Documento10 pagineReview 1meskelu danielNessuna valutazione finora

- Haddish (Repaired)Documento53 pagineHaddish (Repaired)Sarah PugelNessuna valutazione finora

- Remotesensing 15 04298 v2Documento27 pagineRemotesensing 15 04298 v2nihel khlifNessuna valutazione finora

- $Vwxg/Riwkhsurgxfwlrqfrvwvriwzrsrphjudqdwhydulhwlhv Jurzqlqsrrutxdolw/VrlovDocumento5 pagine$Vwxg/Riwkhsurgxfwlrqfrvwvriwzrsrphjudqdwhydulhwlhv Jurzqlqsrrutxdolw/Vrlov105034412Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Stochastic Investigation of Rainfall Variability in Relation To Legume Production in Benue State-NigeriaDocumento7 pagineA Stochastic Investigation of Rainfall Variability in Relation To Legume Production in Benue State-NigeriatheijesNessuna valutazione finora

- 3 Crop Production in Ethiopia: Regional Patterns and TrendsDocumento31 pagine3 Crop Production in Ethiopia: Regional Patterns and TrendsEndale AmdekiristosNessuna valutazione finora

- Country Operations Business Plan: Philippines, 2013 - 2015: Assessment, Strategy and Roadmap. Manila (9 September)Documento7 pagineCountry Operations Business Plan: Philippines, 2013 - 2015: Assessment, Strategy and Roadmap. Manila (9 September)ajjumamilNessuna valutazione finora

- Vietnam PDFDocumento17 pagineVietnam PDFgau shresNessuna valutazione finora

- Agrometeorology and Wheat ProductionDocumento12 pagineAgrometeorology and Wheat ProductionRoci AVNessuna valutazione finora

- Turkish Agriculture Industry Report: Republic of Turkey Prime MinistryDocumento19 pagineTurkish Agriculture Industry Report: Republic of Turkey Prime Ministrynoisysilence22291Nessuna valutazione finora

- Enhancing Environmental Performance With Winter Cover Cropping After Potato Harvest in Eastern CanadaDocumento16 pagineEnhancing Environmental Performance With Winter Cover Cropping After Potato Harvest in Eastern CanadaballysaNessuna valutazione finora

- Agriculture 12 01816 v2Documento19 pagineAgriculture 12 01816 v2Dr. Alejandro Perez-RosalesNessuna valutazione finora

- ETC&KC of The Crop in MelkassaDocumento9 pagineETC&KC of The Crop in Melkassaمهندس ابينNessuna valutazione finora

- Small Farmers and Organic-Banana Production in The Dominican RepublicDocumento22 pagineSmall Farmers and Organic-Banana Production in The Dominican RepublicojldmNessuna valutazione finora

- Harvesting Paradise : A Guide to Tropical AgricultureDa EverandHarvesting Paradise : A Guide to Tropical AgricultureNessuna valutazione finora

- Summary Of "The Year 2000 And The Economy" By Beatriz Nofal: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESDa EverandSummary Of "The Year 2000 And The Economy" By Beatriz Nofal: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit-3.1.2-Sleeve and Cotter JointDocumento18 pagineUnit-3.1.2-Sleeve and Cotter JointAsvath Guru100% (2)

- Bai Tap Tieng Anh Lop 8 (Bai 13)Documento4 pagineBai Tap Tieng Anh Lop 8 (Bai 13)nguyenanhmaiNessuna valutazione finora

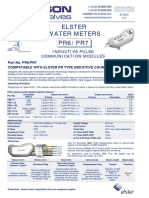

- Data Sheet No. 01.12.01 - PR6 - 7 Inductive Pulse ModuleDocumento1 paginaData Sheet No. 01.12.01 - PR6 - 7 Inductive Pulse ModuleThaynar BarbosaNessuna valutazione finora

- Quality Factor of Inductor and CapacitorDocumento4 pagineQuality Factor of Inductor and CapacitoradimeghaNessuna valutazione finora

- ReliabilityDocumento5 pagineReliabilityArmajaya Fajar SuhardimanNessuna valutazione finora

- 41403A - Guide - Rev - 12-20-17 - With Edits - 2-16-18Documento167 pagine41403A - Guide - Rev - 12-20-17 - With Edits - 2-16-18Ronald KahoraNessuna valutazione finora

- Education in America: The Dumbing Down of The U.S. Education SystemDocumento4 pagineEducation in America: The Dumbing Down of The U.S. Education SystemmiichaanNessuna valutazione finora

- A Project Report On A Study On Amul Taste of India: Vikash Degree College Sambalpur University, OdishaDocumento32 pagineA Project Report On A Study On Amul Taste of India: Vikash Degree College Sambalpur University, OdishaSonu PradhanNessuna valutazione finora

- AtelectasisDocumento37 pagineAtelectasisSandara ParkNessuna valutazione finora

- Penilaian Akhir TahunDocumento4 paginePenilaian Akhir TahunRestu Suci UtamiNessuna valutazione finora

- 2 Dawn150Documento109 pagine2 Dawn150kirubelNessuna valutazione finora

- As ISO 9919-2004 Pulse Oximeters For Medical Use - RequirementsDocumento10 pagineAs ISO 9919-2004 Pulse Oximeters For Medical Use - RequirementsSAI Global - APACNessuna valutazione finora

- M.Info M.Info: Minfo@intra - Co.mzDocumento8 pagineM.Info M.Info: Minfo@intra - Co.mzAntonio ValeNessuna valutazione finora

- 2022-Brochure Neonatal PiccDocumento4 pagine2022-Brochure Neonatal PiccNAIYA BHAVSARNessuna valutazione finora

- Characteristics of Testable HypothesesDocumento30 pagineCharacteristics of Testable HypothesesMarivic Diano67% (3)

- Senior Project RiceberryDocumento76 pagineSenior Project RiceberryIttisak PrommaNessuna valutazione finora

- 208-Audit Checklist-Autoclave Operation - FinalDocumento6 pagine208-Audit Checklist-Autoclave Operation - FinalCherry Hope MistioNessuna valutazione finora

- J130KDocumento6 pagineJ130KBelkisa ŠaćiriNessuna valutazione finora

- Soil SSCDocumento11 pagineSoil SSCvkjha623477Nessuna valutazione finora

- Maintenance Instructions, Parts Identification & Seal Kits For Series 2H / 2HD / 2HB & 3H / 3HD / 3HBDocumento10 pagineMaintenance Instructions, Parts Identification & Seal Kits For Series 2H / 2HD / 2HB & 3H / 3HD / 3HBAtaa AssaadNessuna valutazione finora

- Mainstreaming Gad Budget in The SDPDocumento14 pagineMainstreaming Gad Budget in The SDPprecillaugartehalagoNessuna valutazione finora

- Village Survey Form For Project Gaon-Setu (Village Questionnaire)Documento4 pagineVillage Survey Form For Project Gaon-Setu (Village Questionnaire)Yash Kotadiya100% (2)

- Introduction and Vapour Compression CycleDocumento29 pagineIntroduction and Vapour Compression Cycleمحسن الراشدNessuna valutazione finora