Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Social Networks Support Cliques and Kinship

Caricato da

Kavirm350 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

145 visualizzazioni18 pagineSocial Networks Support Cliques and Kinship

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoSocial Networks Support Cliques and Kinship

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

145 visualizzazioni18 pagineSocial Networks Support Cliques and Kinship

Caricato da

Kavirm35Social Networks Support Cliques and Kinship

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 18

SOCIAL NETWORKS, SUPPORT

CLIQUES, AND KINSHIP

R. I. M. Dunbar

U n i v e r s i t y o f L i v e r p o o l

M. Spoors

U n i v e r s i t y C o l l e g e L o n d o n

Data on the number of adul t s t hat an i ndi vi dual contacts at least once

a mont h i n a set of British popul at i ons yi el d est i mat es of net wor k

sizes that correspond closely to t hose of the typical "sympat hy group"

size i n humans. Men and women do not differ i n t hei r total net wor k

size, but women have more femal es and more ki n i n t hei r net wor ks

t han men do. Ki n account for a si gni f i cant l y hi gher pr opor t i on of net -

work member s t han woul d be expected by chance. The numbe r of ki n

i n the net wor k increases i n pr opor t i on to the size of the fami l y; as a

result, peopl e from large fami l i es have proport i onat el y fewer non- ki n

i n t hei r net works, suggest i ng t hat there is ei t her a t i me const rai nt or a

cogni t i ve const rai nt on net wor k size. A smal l i nner cl i que of the net -

work funct i ons as a support group from whom an i ndi vi dual is par-

ticularly l i kel y to seek advice or assi st ance i n t i me of need. Ki n do not

account for a si gni fi cant l y hi gher pr opor t i on of the support cl i que t han

they do for the wi der net work of regul ar social contacts for ei t her men

or women, but each sex exhi bi t s a st rong preference for member s of

their own sex.

KEY WORDS: Net works; Ki nshi p; Sex di fferences; Fami l y size;

Support group.

Received August 22, 1994; accepted January 23, 1995.

Addr es s all correspondence to R. I. M . Dunbar , De p a r t me n t o f Psychology, U n i v e r s i t y o f Li v e r -

pool, P. O. Box 147, Liverpool L69 3 B X , England.

Copyright 9 1995 by Walter de Gruyter, Inc. New York

Human Nature, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 273-290. 1045-6767/95/$1.00 + .10

273

274 Human Nature, Vol. 6, No. 3, 1995

There has been considerable interest in both the sociological and the

anthropological literatures regarding the people with whom individuals

interact. The current view emphasizes the fact that an individual lies at

the focal point of a number of partially overlapping social networks,

each of which is oriented towards a different social context or purpose

(Milardo 1988). Thus, an individual may have a number of different sets

of friends based on work, leisure activities (such as an interest group or

sports club), church, the extended family, and so on. Moreover, the pat-

tern of relationships may change over an individual' s lifetime (Larson

and Bradney 1988).

It is clear, however, that there are limits to the number of contacts

that an individual can maintain over a given period of time. "Small

world" experiments in which individuals are asked to send messages

to distant parts of the world via a chain of contacts rooted in their cir-

cle of personal acquaintances suggest that the number of people on

whom any one individual can call for such favors is limited to

between 130 and 250 (Killworth et al. 1984). This estimate of the size

of an individual' s social world is on the same order as that estimated

from the size of the modern human neocortex based on a relationship

between neocortex size and group size derived from primates (Dun-

bar 1993).

Many of these individuals, however, are likely to be acquaintances

rather than intimate friends. It is widely recognized that this inner cir-

cle of more intense relationships plays a crucial role in mediating the

individual' s interactions with (and place within) the local communi t y

(Bott 1971; Milardo, ed. 1988; Mitchell 1969; Young and Willmott 1957).

Estimates of the size of this inner circle (the so-called sympat hy group)

have yielded values on the order of 10-12 individuals (Buys and

Larsen 1979). In this case, the estimates were obtained by asking indi-

viduals to list all the people whose death they woul d find personally

devastating, but they probably correspond to those people with whom

an individual keeps in regular contact. Net work sizes estimated from

frequency of contact have yielded values ranging from seven in U.S.

college freshmen (Hays and Oxley 1986) to 16.6 in young women

(McCannell 1988) and around 20 in married couples (Rands 1988). Dif-

ferences in both the criteria used to define network membership and

the stages of the life cycle at which networks are sampled are largely

responsible for the differences found between studies. Nonetheless, it is

clear that all these values tend to converge on the same group size

(10-15 individuals).

One reason for our interest in the size of these groupings derives from

the suggestion that language may have evolved to allow the exchange

of social information in order to facilitate the integration of relatively

Kinship and Network Size 275

large social groups (Dunbar 1993). There is some evidence to suggest

that the constraints in this respect derive not so much from the ability

to monitor all individuals in the communi t y but rather from the need to

monitor the activities and doings of one' s key social allies (principally,

presumably, one' s family and i mmedi at e friends) (Kudo et al. 1995). One

aim of this study, then, was to try to determine the size and composi-

tion of the inner circle (or network) that might constitute the focus of an

individual' s social interest.

Kinship is known to play an important role in both human social rela-

tionships and the structure of human groups in traditional as well as

modern postindustrial societies (see, for example, Firth 1956; Hughes

1988; Keesing 1975). Hames (1979) has shown that Ye' kwana villagers of

Venezuela interact more often with individuals who are closely related

to them, while Bert6 (1988) found that among the horticultural K'ekchi"

of Central America the availability of a network of kin is an i mport ant

determinant of the amount of land an individual can cultivate. The

extent to which kinship is a consideration in the creation of social net-

works in industrial societies remains unclear, however, even t hough

interview-based studies suggest that considerable weight is placed on

kinship in contemporary European societies (Bott 1971; Young and Will-

mott 1957).

We examine here the role that kinship plays in determining the com-

position of an individual' s social network in a modern European soci-

ety. Our main concern is with the circle of friends and relations wi t h

whom an individual maintains regular contact. Given that we can iden-

tify such a group, we can then ask what role kinship plays in determin-

ing its composition. In addition, we examine the size and composition

of the inner clique of intimates (the support clique) that individuals

would normally approach for advice or assistance when in difficulty. We

might expect kinship to be an important factor in the selection of sup-

port clique members because the opport uni t y for reciprocal altruism is

likely to be much less in situations of advice and/ or help than it is with

respect to social interaction.

Studies of social networks have t ended to focus either on quantitative

analyses of network size and structure (Burt 1982; Coleman 1964; Knoke

and Kuklinski 1982) or on more descriptive studies of individuals' net-

works and their role in facilitating social life (Bott 1971; Fischer 1982;

studies in Mitchell, ed. 1969 and Milardo, ed. 1988). In general, the more

quantitative studies have typically concerned themselves wi t h large-

scale structures at the societal level, often with a focus on organizations

rather than individuals (e.g., business and political networks) and the

functional roles that exist within organizations of this kind. In contrast,

studies of personal and support networks have t ended to be based on

276 Human Nature, Vol. 6, No. 3, 1995

in-depth interviews with a handful of individuals, with the focus on

how individuals relate to their immediate social circles. Our aim here is

to provide a preliminary assessment of the size of an individual' s net-

work of intimates and the extent to which kin contribute to it.

M E T H O D S

A questionnaire was designed which asked respondents to list the first

names of individuals whom they (a) lived with, ( b ) contacted wi t h vary-

ing degrees of frequency (termed their n e t w o r k ) , and (c) relied on for

advice and/ or help at the personal level (termed the s u p p o r t c l i q u e ) , as well

as ( d ) the size of their extended biological family (defined as all individu-

als related to the subject by r > 0.125, assuming full paternity certainty).

Contacts were defined as social exchanges involving face-to-face, letter, or

telephone interaction. Respondents were specifically asked not to include

business and professional contacts, unless the individuals concerned were

deemed to be personal friends. In responding to ( a ) - ( c ) , subjects were

required to distinguish between relatives and nonrelatives, with the crite-

rion for a relative being limited to full cousins or more closely related indi-

viduals. Subjects were asked to list the first names of individuals they

contacted daily, twice weekly, weekly, and at least once a month, as well

as those individuals they contacted regularly but less than once a month.

Considerable effort has been put into questionnaire design duri ng the

past decade (see Milardo 1988, and references therein). The burden of

this work has been to suggest that questionnaires that take more than a

few minutes to complete and have too many instructions and/ or more

than 10-12 name-eticiting questions tend to result in loss of concentra-

tion. The questionnaire was therefore designed to contain just four sets

of questions, each accompanied by a series of boxes to be filled in. The

questionnaire was tested on students and refined until it required no

more than 5 minutes to complete.

The questionnaire design used a recall procedure rather than asking

individuals to list all those whom they actually contacted during a set

period of time from receipt of the questionnaire. This approach was

largely chosen for speed and convenience. Although recall procedures

run a risk that respondents will overlook contacts they have made (see

Bernard et al. 1982, 1984), the relatively short time depth used in the pres-

ent case should tend to minimize this source of inaccuracy. In contrast,

prospective questionnaires greatly increase the load on the subject

because they require respondents to keep a daily tally of whom t hey

have contacted; as a result, under-reporting by those who lead especially

busy lives tends to increase. In addition, they t end to underestimate the

Kinship and Network Size 277

actual network size because individuals may not always be able to con-

tact all their normal interactees duri ng a particular sample period (e.g.,

because they are away or other unusual circumstances intervene). In

order to try to circumvent some of these problems, subjects were asked

to say whom they normally contacted duri ng a given time period. It was

felt that this would reduce both errors of omission and the number of

trivial contacts listed (i.e., those casual contacts who were not members

of the respondent' s circle of friends).

Questionnaires were distributed at five different locations within Eng-

land and Scotland. These respondents were not chosen to be a represen-

tative sample in any conventional sense, but simply to provide a broad

sample of subjects of different age, background, and geographical loca-

tion. In each case, a single assistant was responsible for handi ng out and

collecting completed questionnaires. Each assistant was instructed to tell

respondents only that the purpose of the questionnaire was to find out

about people' s social contacts. They were, however, allowed to help with

the filling in of questionnaires if requested to do so. Questionnaires were

distributed only to subjects between 18 and 65 years of age who were

members of a golf club or staff at a hospital in Lincolnshire, staff at an

empl oyment consultancy in Aberdeen, employees at a farm machinery

factory in Doncaster, and personal contacts within the London area. With

just a few exceptions, only one respondent was sampled per household.

Individuals over 65 years of age were excluded from the sample because

they are known to have reduced network sizes owing to greater vulnera-

bility to infirmity as well as deaths among lifelong friends (Bliezner 1988;

Brown 1981). Similarly, children and younger teenagers were excluded

because their networks are known to be atypical in both composition and

stability (Foot et al_ 1980; Levinger and Levinger 1986; Thorne 1986).

A total of 155 questionnaires were returned from the 170 given out.

The resulting response rate of 91% is high by normal questionnaire stan-

dards and can largely be attributed to the fact that in most cases the sub-

jects were themselves known to the assistants distributing the

questionnaires. Personal loyalty is thus likely to have been an important

factor influencing the completion of questionnaires. Of the returned

questionnaires, 54 were excluded from the analysis: the majority had

been incompletely (or in a few cases, incorrectly) filled in (mostly fail-

ure to identify contacts by sex), but 11 were spoiled in transit or other-

wise unreadable and 8 contained too many comments and queries to be

considered reliable. So far as we could tell, incomplete and spoiled ques-

tionnaires were not biased in favor of any particular category of subject

by sex, age, or domestic status. The remaining 101 subjects consisted of

34 men and 67 women. Of these, 24.8% (5 men and 20 women) were

single, 50.5% (18 men and 33 women) lived with a partner but did not

278 Human Nature, Vol. 6, No. 3, 1995

ha ve d e p e n d e n t of f s pr i ng l i vi ng wi t h t hem, 21.8% (9 me n a nd 13

wome n) l i ved wi t h a pa r t ne r a nd d e p e n d e n t chi l dr en, a nd t wo wo me n

l i ved al one wi t h d e p e n d e n t chi l dr en.

Ou r c onc e r n was t o i dent i f y t he set of p r i ma r y associ at es ( " f r i e nds "

in t he nor ma l me a ni ng of t he t er m) t hat an i ndi vi dua l has. Thi s is t he

set of pe opl e wh o s e act i vi t i es a nd l i fe hi s t or i es ar e of suf f i ci ent i nt er est

t o an i ndi vi dua l f or t hat pe r s on t o be wi l l i ng t o ma ke s ome ef f or t t o

keep up t o dat e. Rat her t ha n ask r e s p o n d e n t s t o s peci f y t hes e i ndi vi du-

als us i ng t hei r o wn cri t eri a, we pr e f e r r e d t o us e a mor e obj ect i ve cri t e-

r i on t hat coul d be appl i ed u n i f o r ml y acr oss t he ent i r e s ampl e. The

n u mb e r of cont act s was bi modal , wi t h pe a ks i n t he we e kl y a nd mo n t h l y

f r e que nc y cat egor i es. We t her ef or e us e d t he f r e que nc y wi t h whi c h i ndi -

vi dual s we r e cont act ed on at l east a mo n t h l y basi s as t he cr i t er i on f or

i ncl usi on i n a subj ect ' s net wor k. We t ook t he vi e w t hat i ndi vi dua l s wh o

cont act ed each ot her less of t en t ha n onc e a mo n t h we r e unl i kel y t o

r e ma i n up t o dat e wi t h each ot he r ' s mo r e i nt i mat e exper i ences , a nd t hus

fell out s i de t he s cope of t he pr es ent concer n.

Al l st at i st i cal t est s ar e t wo- t ai l ed. Dat a we r e l og- t r a ns f or me d i n o r d e r

t o nor ma l i z e val ues f or all pa r a me t r i c st at i st i cal anal yses.

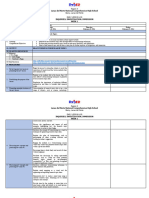

RESULTS

Network Si ze and Composi t i on

Fi gur e 1 s hows t he di s t r i but i on of n e t wo r k si zes in t he s ampl e. The

me a n ne t wor k si ze f or all subj ect s was I I . 6 ( r ange 0- 30, sd = 5.64; N =

101). The di s t r i but i on exhi bi t s s ome d e g r e e of bi modai i t y, wi t h pe a ks at

ne t wor k si zes of 6 a nd 11-12, s ugges t i ng t hat it ma y be pos s i bl e t o di s-

t i ngui s h be t we e n mor e- a nd l ess- soci abl e i ndi vi dual s . Bef or e we can

saf el y d r a w t hi s concl usi on, howe ve r , we ne e d t o check t hat t he

bi moda l i t y is not due t o c onf oundi ng var i abl es s uch as g e n d e r or

domes t i c ci r cumst ances.

Ther e was a sl i ght , but nons i gni f i cant , g e n d e r di f f er ence i n n e t wo r k

size: wo me n a ve r a ge d a ne t wor k of 12.4 i ndi vi dua l s ( N = 67) c o mp a r e d

wi t h 10.9 (N = 34) f or me n ( Ma nn- Whi t ne y t est , z = -1. 006, P -- 0.315).

Thi s is l ar gel y a c ons e que nc e of t he f act t hat t he di s t r i but i on of n e t wo r k

si zes f or wo me n was mor e s ke we d ( l onger t ai l t o r i ght ) t han t hat f or t he

men. Moda l n e t wo r k si ze was v e r y si mi l ar f or t he t wo sexes.

As mi ght be ant i ci pat ed, t he dome s t i c st at us of subj ect s di d ha ve

s ome i nf l uence on t hei r ne t wor k size. Si ngl e subj ect s ha d a me a n net -

wo r k si ze of 15.4 ( r ange 7-30, sd = 6.20; N = 25), c o mp a r e d wi t h me a n s

of 11.1 ( r ange 0-25, sd = 5.55; N = 51) f or c oupl e s wi t h o u t chi l dr en at

12-

10-

8 -

0

:::1 6 -

0 "

r i I i I I I I L I l I I I I I

0 1 2 3 4 6 7 1 0 1 1 1 2 1 3 1 4 1 5 1 6 1 7 1 8 1 9 2 0 2 1 2 2 2 3 2 4 2 5 2 6 2 7 2 8 2 9

Kinship and Network Size 279

Network size

Figure 1. Distribution of network sizes.

home and 8.7 (range 0-19, sd = 4.16; N = 24) for couples with dependent

children (including the two single mothers). However, the variance

within each category was considerable, and the differences bet ween

them were not significant (Mann-Whitney tests: singles vs couples with-

out children, z = 0.99, P = 0.322; couples wi t hout children vs couples

with children, z = 1.48, P = 0.139). For all three distributions, however,

the same pattern is evident: 40.0% of singles had net works of size 6-12

compared with 66.7% of couples both with and wi t hout dependent chil-

dren. The differences are largely in the lengths of the tails on either side

of the modal values. Singles had a t runcat ed l ower range, whereas cou-

ples with children had a truncated upper range, while couples wi t h no

dependent children had a more even distribution.

We examined gender differences in the composition of the net work

using a MANOVA with respondent ' s gender as the i ndependent vari-

able and the proportions of contacts that were male (as opposed to

female) and kin (as opposed to non-kin) as the dependent variables. (For

these purposes, kin were defined as individuals related to the subject by

r > 0.125.) This examination revealed that the t wo sexes differed signifi-

cantly in terms of the ratio of male to female contacts (mean percent of

280 Huma n Nat ure, Vol. 6, No. 3, 1995

n e t wo r k me mb e r s t hat we r e mal e: 67. 7% f or me n a n d 30. 8% f or wo me n ;

F1,94 = 47.75, P < 0.001), n u mb e r of f e ma l e ki n c ont a c t e d ( me a n s of 1.88

f or me n a nd 3.06 f or wo me n : F1,94 = 9.64, P = 0.002), n u mb e r of ma l e

non- ki n cont act ed ( me a ns of 5.62 f or me n a n d 1.75 f or wo me n : F1,94 =

52.81, P < 0.001), a nd n u mb e r of f e ma l e n o n - k i n c ont a c t e d ( me a n s of

1.65 f or me n a nd 5.51 f or wo me n : F1,94 = 57.97, P < 0.001), b u t not i n

t e r ms of t he n u mb e r of ma l e ki n c ont a c t e d ( me a ns of 1.74 f or me n a n d

2.06 f or wo me n : F1,94 = 0.14, P = 0.705). I n s u mma r y , wo me n ha d a

l ar ger n u mb e r of f e ma l e f r i ends a n d r el at i ves i n t hei r n e t wo r k s , wh e r e a s

me n h a d a l ar ger n u mb e r of ma l e f r i ends , wi t h ki n b e i n g s i gni f i cant l y

l ess i mp o r t a n t f or me n t ha n f or wo me n .

The r e we r e no di f f er ences i n t he n u mb e r of n o n - k i n c ont a c t e d

mo n t h l y ( me a ns of 7.26 f or me n a n d 7.25 f or wo me n ) , or i n t he p r o p o r -

t i on of non- ki n cont act ed at l east once a mo n t h wh o we r e c ont a c t e d at

l east once a we e k ( me a ns of 39.3% f or me n a n d 43. 9% f or wo me n : Ma n n

Wh i t n e y t est , z = 0.99, P = 0.327). Ho we v e r , t her e wa s a s i gni f i cant di f -

f er ence i n t he p r o p o r t i o n of all mo n t h l y non- ki n ma l e cont act s t hat we r e

cont act ed at l east we e k l y ( me a ns of 81. 4% f or me n a n d 22. 8% f or

wo me n : Ma n n - Wh i t n e y t est , z = --4.78, P < 0.001).

The r e wa s no di f f er ence b e t we e n t he s exes i n t he p r o p o r t i o n of t hei r

e x t e n d e d f ami l i es ( def i ned as t he t ot al n u mb e r of l i vi ng i n d i v i d u a l s

r el at ed t o t he subj ect b y r > 0.125) wh o we r e c ont a c t e d mo n t h l y ( me a n s

of 29. 9% out of an a v e r a g e f a mi l y of 12.1 me mb e r s f or me n a nd 36. 3%

out of an a v e r a g e f a mi l y of 14.1 f or wo me n : Ma n n - Wh i t n e y t est , z =

0.18, P = 0.857). Al t h o u g h me n di d not c ont a c t mo r e ma l e ki n t ha n

wo me n di d i n a bs ol ut e t e r ms , t he y di d c ont a c t a hi ghe r p r o p o r t i o n of

t he ma l e s i n t hei r e x t e n d e d f ami l i es t h a n wo me n di d ( me a n s of 48. 8%

of 3.6 ma l e ki n f or me n vs 40. 2% of 5.1 ma l e ki n f or wo me n ; Ma n n -

Wh i t n e y t est , z = - 2. 67, P = 0.008).

Over al l , ki n a c c ount e d f or 37. 5% of t he n e t wo r k , a f i gur e t hat is

a l mos t cer t ai nl y s i gni f i cant l y hi ghe r t ha n wo u l d be e xpe c t e d if p e o p l e

chos e t hei r n e t wo r k me mb e r s at r a n d o m ei t her f r o m t he l ocal p o p u l a -

t i on as a whol e or f r o m t he s u b s a mp l e of t hat p o p u l a t i o n wh o m t he y

k n o w b y si ght . Unf or t unat el y, we c a n n o t t est t he s i gni f i cance of t hi s

be c a us e we do not h a v e a n y a p p r o p r i a t e va l ue s t o us e f or t he nul l

hypot he s i s . Nonet hel es s , ki n ar e l i kel y t o a c c ount f or a r e l a t i ve l y s ma l l

p r o p o r t i o n of all t he i ndi vi dua l s t hat a n y one p e r s o n k n o ws . I f we t a ke

t he l owe r mo r e c ons e r va t i ve f i gur e of 150 a c qua i nt a nc e s f r o m t he " s ma l l

wo r l d " e x p e r i me n t s ( Ki l l wor t h et al. 1984) a n d t he a v e r a g e e x t e n d e d

f a mi l y si ze obt a i ne d i n t hi s s t u d y of 12.1 f or me n a nd 14.1 f or wo me n

(see above) , we wo u l d expect onl y a b o u t 8.1% a n d 9. 4%, r es pect i vel y, of

n e t wo r k me mb e r s t o be ki n if c hos e n at r a n d o m. On t hi s basi s, t he

o b s e r v e d p r o p o r t i o n is cl ear l y s i gni f i cant l y bi a s e d i n f a v o r of ki n f or

Kinship and Network Size 281

bot h sexes: t he p r o p o r t i o n of ki n i n t he n e t wo r k is gr e a t e r t h a n t he

e xpe c t e d va l ue f or 32/ 34 me n (;(2 = 26.47, df = 1, P < 0.001) a n d f or

63/ 66 wo me n ( one wo ma n wi t h a n e t wo r k si ze of 0 wa s e xc l ude d) (X 2

= 54.55, df = 1, P < 0.001).

Network Si ze and Kin Group Si ze

I f t he n u mb e r of i ndi vi dua l s wh o can be ma i n t a i n e d i n a cl ose soci al

n e t wo r k is l i mi t ed ei t her b y t he t i me a va i l a bl e f or i nt e r a c t i on (e.g., Du n -

ba r 1992) or b y cons t r ai nt s i mp o s e d b y t he pr oc e s s i ng c a pa c i t y of t he

cogni t i ve ma c h i n e r y (e.g., Du n b a r 1993), t he n we mi g h t e xpe c t t he r e t o

be an i nve r s e r el at i ons hi p b e t we e n t ot al n e t wo r k si ze a n d t he si ze of t he

fami l y. I n ot he r wor ds , i ndi vi dua l s wh o h a v e l ar ge e x t e n d e d f ami l i es

ma y be mo r e l i kel y t o conf i ne t hei r soci al cont act s t o me mb e r s of t hei r

f ami l y ci rcl e t ha n ar e t hos e i ndi vi dua l s wi t h f e we r cl ose r el at i ves t o

c hoos e f r om.

Fi gur e 2 s ugge s t s t hat t her e is a we a k n e g a t i v e r e l a t i ons hi p b e t we e n

t he n u mb e r s of ki n a nd non- ki n c ont a c t e d at l east mo n t h l y ( Pe a r s on' s r

= -0. 138, t99 = 1.37, P > 0.05). On e l i kel y r e a s on wh y t he c or r e l a t i on is

25

20

15'

10'

Number of non- ki n

9 0 0 0

00 O 9

OO

0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0 9

0 0 0 0 9 9

0 0 0 0 0 9

0 0 9 00

9 00

O 0 9 9 9 9 9 @

@ Q

0 I _k J I I 9 I

0 5 10 15 20 25 30

Number of kin

Figure 2. Number of non-kin contacted at least once a mont h pl ot t ed agai nst

the number of kin contacted at least once a mont h.

282 Human Nature, Vol. 6, No. 3, 1995

poor is t he l ar ge n u mb e r of i ndi vi dual s i n t he l owe r l eft q u a d r a n t ( who

cont act onl y a smal l n u mb e r of bot h ki n a nd non- ki n) . In ot he r wor ds ,

it ma y be t hat f or r el at i vel y asoci al i ndi vi dua l s wh o s e n e t wo r k si ze is

wel l be l ow t he cogni t i ve l i mi t , t he n u mb e r of ki n doe s not r est r i ct t he

n u mb e r of non- ki n cont act ed. If al l subj ect s wh o cont act ed f e we r t ha n

10 i ndi vi dual s ar e excl uded, t he n t he r e is a hi ghl y s i gni f i cant ne ga t i ve

cor r el at i on be t we e n numbe r s of ki n a n d non- ki n cont act ed (r = - 0. 554,

t58 = -5. 06, P < 0.001).

One r eas on f or t hi s s eems t o be t hat i ndi vi dua l s f r om l ar ge f ami l i es

t end t o cont act mor e ki n ( Fi gur e 3: Pe a r s on' s r = 0.397, t99 = 4.30, P <

0.001). In cont r ast , t he n u mb e r of non- ki n cont act ed is not s i gni f i cant l y

r el at ed t o t he si ze of t he f ami l y ( Fi gur e 4: r = - 0. 032, t80 = - 0. 32, P > 0.05;

f or subj ect s wi t h ne t wor ks l ar ger t ha n ni ne me mbe r s : r = - 0. 096, t58 =

-0. 74, P > 0.05); r at her , it ma y be r el at ed mor e cl osel y t o i ndi vi dual s '

r es pect i ve oppor t uni t i e s f or i nt er act i on out s i de t he fami l y.

Thes e r esul t s s ugges t t hat pe opl e pl ace a p r e mi u m on ma i nt a i ni ng

f ami l y cont act s a nd onl y e xt e nd t hei r n e t wo r k of cont act s b e y o n d t he

f ami l y if t hey ha ve s par e capaci t y i n t hei r t ot al n e t wo r k si ze onc e t hei r

ke y f ami l y cont act s ha ve be e n e xha us t e d. Thi s s eems t o be i n d e p e n d e n t

30

25

20

15

10

Number of kin cont act ed

O - . . - 9 9 _ , , ,

0 10 20 30 40

Family si ze

5O

Figure 3. Number of kin contacted at least once a mont h plotted against total

family size.

Kinship and Network Size 283

Number of non-ki n cont act ed

25

20

15

lOq

5

9 9 9 9 9

10 20 30 40

Family size

0

0 5 0

Figure 4. Number of non-kin contacted at least once a mont h plotted against

total family size.

of t he di s t r i but i on of degr ees of ki ns hi p wi t hi n t he f ami l y (i.e., ki ns hi p

densi t y) : n u mb e r of ki n cont act ed is not r el at ed to subj ect ' s me a n de gr e e

of r el at edness, rmean, to all t he me mb e r s of h i s / h e r e x t e n d e d f a mi l y

( Pear s on' s r = 0.092, F1,99 = 0.47, P = 0.496). In ot he r wor ds , f ami l i es wi t h

a hi gher pr opor t i on of cl osel y r el at ed i ndi vi dua l s (e.g., si bl i ngs) do not

s how a ny t e n d e n c y t o i nt er act mor e f r e que nt l y wi t h each ot he r t ha n

t hose wi t h a l owe r pr opor t i on (e.g., f e we r si bl i ngs, mor e cousi ns) . Not e ,

however , t hat i ndi vi dual s do not neces s ar i l y i nt er act wi t h all t he me m-

ber s of t hei r e xt e nde d family. On aver age, me n c ont a c t e d onl y 30.0% of

t he me mb e r s of t hei r e xt e nde d f ami l y at l east once a mont h, whi l e

wo me n cont act ed 36.6% of t hei r f ami l y me mbe r s .

Kinship and the Support Clique

The me a n n u mb e r of i ndi vi dua l s f r om wh o m s u p p o r t wo u l d be

s ought wa s 4.72 ( r ange 0-14, s d = 2.95; N = 101). The r e wa s no di f f er -

ence i n t he si zes of t he s u p p o r t cl i ques of me n a nd wo me n ( me a ns of

4.47 f or 34 me n a nd 4.85 f or 67 wo me n ; Ma n n - Wh i t n e y t est , z = - 1. 18,

284 Huma n Nature, Vol. 6, No. 3, 1995

16-

14-

12-

lO-

e~

6-

0 1 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14

Cl i que size

I Men [ - - ] Women

Figure 5. Distribution of support clique sizes,

P = 0.236). Fi gur e 5 s ugge s t s t hat , as wi t h t he n e t wo r k si ze, t he di s t r i b-

ut i on is b i mo d a l wi t h p e a k s at 2- 3 a n d 5. Di s a g g r e g a t i o n of t he da t a f or

me n a nd wo me n yi e l ds a s i mi l ar pi ct ur e, b u t wi t h s l i ght l y of f set pe a ks :

me n at 2 a nd 5, wo me n at 3 a n d 7. As wi t h t he di s t r i but i on of n e t wo r k

si zes, t he p e a k s in t he si ze of t he s u p p o r t cl i que ma y c o r r e s p o n d t o con-

t r ast s b e t we e n mor e - a nd l es s - s oci abl e i ndi vi dua l s . So me e v i d e n c e t o

s u p p o r t t hi s s ugge s t i on c ome s f r o m t he f act t hat t he si ze of t he s u p p o r t

cl i que is l i near l y r el at ed t o t ot al n e t wo r k s i ze ( Fi gur e 6: Pe a r s o n ' s r =

0.427, t97 = 4.651, P < 0.001) a nd r e pr e s e nt s a n a v e r a g e of 39.8% of t he

i ndi vi dua l ' s t ot al cont act ne t wor k. The r e s e e m t o be no c o n s p i c u o u s di f -

f er ences b e t we e n t he sexes i n t hi s r es pect .

Of t he s u p p o r t cl i que, 22.6% we r e t ypi c a l l y f e ma l e ki n, 33. 5% f e ma l e

non- ki n, 17.1% ma l e ki n, a nd 26. 8% ma l e non- ki n. The p r o p o r t i o n of

s u p p o r t sour ces t hat we r e ki n doe s not di f f er f r o m t he p r o p o r t i o n of t ot al

mo n t h l y cont act s (i.e., n e t wo r k si ze) t hat we r e ki n ( Wi l coxon ma t c h e d

pai r s t est s: f or me n, z = --0.18, P = 0.860; f or wo me n , z = - 0. 62, P = 0.536);

nor doe s t he p r o p o r t i o n of t he s u p p o r t cl i que t hat wa s of t he o p p o s i t e

sex di f f er f r o m t he p r o p o r t i o n i n t he t ot al n e t wo r k ( Wi l coxon t est s: f or

me n, z = -1. 172, P = 0.086; for wo me n , z -- - 1. 91, P = 0.056). Thi s s ug-

Kinship and Network Size 285

S u p p o r t c l i q u e s i z e

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

- 0- - WOmeN

[ ] [ ]

Men

9 9

9 9 9 ...... O

E 3 9 9 ' 9

9 /

/ 9 ..... o ~ o 9 [] 9 9

. . . . . . [ ] ' " [ ] ~ q L ~ ~ [ ] E ] [ ] 9 9

9 [ 3 [ 3 0 0 9

I [ ] ~ t I I i

5 10 15 2 0 2 5 3 0

Network si ze

3 5

Figure 6. Support clique size pl ot t ed agai nst total net work size.

gest s t hat , over al l , t he s u p p o r t cl i que is c hos e n on t he s a me bas i s as t he

wi d e r n e t wo r k of f r i ends, a nd it a p p e a r s t o be a mo r e or l ess r a n d o m

s a mp l e of t hat wi d e r ne t wor k. None t he l e s s , on a ve r a ge , 40% of s u p p o r t

cl i que me mb e r s we r e cl ose ki n: t he p r o p o r t i o n of ki n in t he s u p p o r t

cl i que wa s hi ghe r t han wo u l d be e xpe c t e d if t he y we r e d r a wn at r a n d o m

f r om an a c qua i nt a nc e s n e t wo r k of a b o u t 150 f or 2 4 / 3 3 me n a n d 5 4 / 6 6

wo me n (X2 = 6.82 a nd 26.73, r es pect i vel y; df = 1, P < 0.01 i n bot h cases).

As wi t h t ot al n e t wo r k si ze, b o t h me n a n d wo me n t e n d e d t o sel ect t he

t wo sexes of ki n wi t h a b o u t e qua l f r e q u e n c y as s u p p o r t s our c e s ( me a n

pe r c e nt a ge of ki n s u p p o r t s our c e s t hat we r e mal e: 49. 1% f or me n a n d

40.6% f or wo me n ) . Ho we v e r , a mo n g n o n - k i n s our ces of s u p p o r t , me n

a nd wo me n s h o we d s t r i ki ng pr e f e r e nc e s f or t hei r o wn sex ( me a n per -

cent of ma l e s a mo n g non- ki n s u p p o r t sour ces: 26. 6% f or wo me n a n d

82.5% f or me n, Ma n n - Wh i t n e y t est , z = 32.74, P < 0.001).

DI S CUS S I ON

We h a v e s h o wn t hat t he n u mb e r of i ndi vi dua l s c ont a c t e d on a r e gul a r

basi s (i.e., at l east once a mo n t h ) c o n f o r ms cl os el y t o t hat o b t a i n e d f r o m

e s t i ma t e s of t he si ze of " s y mp a t h y g r o u p s . " I n s el ect i ng t he me mb e r s of

286 Human Nature, Vol. 6, No. 3, 1995

this group, both sexes contact kin di sproport i onat el y more often than

they do non-kin; as a result, the number of kin available ultimately lim-

its the number of non-kin that can be i ncl uded in the network. Women

contact kin more often than men do, while both sexes exhibit a strong

t endency for contacts with their own sex to be more common than con-

tacts with the opposite sex. The inner clique of individuals from whom

support or advice might be sought tends to mirror these preferences

rather closely.

These results are generally in line with those report ed by both Rands

(1988) and Booth (1972) for Nort h Ameri can populations. Booth (1972)

noted that while there were no differences in net work size bet ween men

and women, there did seem to be a sex difference in social participation:

men were more socially active than women, but women mai nt ai ned

stronger emotional ties with their contacts and had more ties with kin

than men did.

Our results suggest that the sizes of both net works and support

cliques are bimodal. Although part of the difference bet ween small and

large networks can be attributed to the reproduct i ve status of individu-

als, it seems that there is some residual variation in net work size that is

due to differences in sociability. Al t hough net work size is known to vary

with life history stage (Larson and Bradney 1988), the possibility

remains that some of the variance in net work size is due to differences

in personality. We are currently exploring this possibility in more detail.

The preference for kin over non-kin seems to be in line with what

woul d be expected from the theory of kin selection (that individuals will

prefer to associate with and/ or be altruistic towards kin when all other

things are equal). In a now classic st udy of a worki ng class communi t y in

the east end of London during the 1950s, Young and Willmott (1957)

found a similar t endency for male and female net works to be distinct and

largely sex-specific. They also noted that kinship played a particularly

important role in female networks, with mot hers and daught ers formi ng

what amount to mutually supportive alliances. Bott (1971) also report ed

a t endency for maternal relatives to be more i mport ant than paternal rel-

atives in the social lives of London middle-class families. The present

study provides quantitative support for these largely informal studies; it

also suggests that these effects have remai ned stable despite the enormous

changes that have taken place in British society over the past half century.

These results appear to be at odds wi t h the view that human societies

are typically patrilocal (e.g., Foley and Lee 1989; Levi-Strauss 1969; Rod-

seth et al. 1991), such that in some cases women' s kinship bonds are

weakened or even severed. One possible reason why female kinship

bonds may become relatively more i mport ant in moder n industrial soci-

eties is that groups of males are no longer able to monopol i ze resources

Kinship and Network Size 287

or ot her s our ces of i n v e s t me n t t hat wo me n n e e d f or s ucces s f ul r e pr o-

duct i on. I n soci et i es wh e r e ma l e ki n- ba s e d al l i ances a l l ow me n t o

mo n o p o l i z e s uc h ser vi ces, wo me n ma y be f or ced t o c hoos e b e t we e n

t hes e s er vi ces a n d t hei r o wn ki ns hi p ties. I n t he a bs e nc e of mo n o p o l i z -

abl e ser vi ces, wo me n ma y f i nd t hat t hei r o wn ki n- ba s e d al l i ances ar e

mo r e va l ua bl e a n d me n ma y t he n be l ess i ncl i ned t o c ont i nue s e r vi c i ng

t hei r o wn ki ns hi p ne t wor ks .

The f i ndi ng t hat ki n do not p l a y a mo r e p r o mi n e n t r ol e i n t he s up-

por t cl i que t ha n t he y do in t he f r i e nds hi p n e t wo r k wa s , h o we v e r , une x-

pect ed. That t he y do not mi g h t refl ect t he f act t hat , i n mo d e r n i ndus t r i a l

soci et i es, i ndi vi dua l s of t en l i ve t oo f ar f r o m t hei r i mme d i a t e ki n t o be

abl e t o us e t h e m f or he l p in t i mes of i mmi n e n t crisis. Unf or t una t e l y, we

di d not as k i ndi vi dua l s wh e t h e r t hey l i ved n e a r t hei r ki n ( our c onc e r n

wa s s i mp l y wi t h wh e t h e r or not t he y contacted t hem) , so we ar e u n a b l e

t o d e t e r mi n e wh e t h e r t hos e wh o pr e f e r r e d f r i e nds as s our c e s of h e l p di d

so be c a us e t he y l acked n e a r b y ki n. Al t h o u g h t he e t h n o g r a p h i c l i t er at ur e

s ugge s t s t hat ki n ar e still wi d e l y s een as a p r i ma r y s our c e of uns t i nt i ng

s u p p o r t be c a us e " bl ood is t hi cker t ha n wa t e r " (see, f or e x a mp l e , Bot t

1971; Du n b a r et al. 1995; La r s on a nd Br a d n e y 1988), t he mobi l i t y t ypi cal

of mo d e r n s oci et y ma y ma k e it di f f i cul t f or i ndi vi dua l s t o be as i nt i ma t e

wi t h ge ogr a phi c a l l y di s t ant r el at i ves as t he y ar e wi t h unr e l a t e d f r i e nds

wh o m t hey see r egul ar l y. I nde e d, Bot t (1971) n o t e d a t e n d e n c y f or ki n-

s hi p t i es t o we a k e n wh e n r el at i ves mo v e d a wa y ( es peci al l y wh e n t he y

we r e pe r c e i ve d as d o i n g so i n or de r t o be t t e r t h e ms e l v e s soci al l y) .

We t hank Lilian Cameron, Barbara Forest, Jean Scott, Mary Spoors, and Lisa White

for help with distributing the questionnaires and the anonymous referees for their

helpful comment s.

Robin Dunbar, B.A., Ph.D., until recently a professor of biological anthropology at Univer-

sity College London, is professor of psychology at the University of Liverpool. His main re-

search interests concern mating systems and the evolution of mammalian social systems.

Matt Spoors, B.Sc., M.Sc., teaches at St Hugh' s School, Grantham (England).

REFERENCES

Bernard, H. R., P. D. Killworth, and L. Sailer

1982 I nf or mant Accuracy in Social Net wor k Data, V: An Experi ment al

At t empt to Predict Actual Communi cat i on from Recall Data. Social Science

Research 11:30-66.

1984 On the Validity of Retrospective Data: The Probl em of I nf or mant Accu-

racy. Annual Review of Anthropology 13:495-518..

288 Huma n Nat ure, Vol. 6, No. 3, 1995

Bert6, N.

1988 K' ekchi ' Horticultural Labor Exchange: Product i ve and Reproduct i ve

Implications. In Human Reproductive Behaviour, L. Betzig, M. Borgerhoff Mul-

der, and P.Turke, eds. Pp. 83-96. Cambri dge: Cambr i dge Uni versi t y Press.

Bliezner, R.

1988 Indi vi dual Devel opment and Int i mat e Relationships in Mi ddl e and

Late Adulthood. In Families and Social Networks, R. M. Milardo, ed. Pp.

147-167. Newbur y Park, California: Sage Publications.

Booth, A.

1972 Sex and Social Participation. American Sociology Review 37:183-192.

Bott, E.

1971 Family and Social Network, revised edition. London: Tavistock Publications.

Brown, B. B.

1981 A Lifespan Approach to Friendship: Age-related Di mensi ons of an

Ageless Relationship. In Research in the Interweave of Social Roles, Vol. 2:

Friendship, H. Z. Lopata and D. R. Maines, eds. Pp. 23-50. Greenwich, Con-

necticut: J. A. I.

Burt, R. S.

1982 Towards a Structural Theory of Action: Network Models of Social Structure,

Perceptions and Action. New York: Academi c Press.

Buys, C. J., and K. L. Larsen

1979 Human Sympat hy Groups. Psychology Reports 45:547-553.

Coleman, J. S.

1964 Introduction to Mathematical Sociology. London: Collier-Macmillan.

Dunbar, R. I. M.

1992 Time: A Hi dden Constraint on the Behavioural Ecology of Baboons.

Behavioural Ecology and Sociobiology 31:35-49.

1993 Coevol ut i on of Neocortex Size, Gr oup Size and Language in Humans.

Behavioral and Brain Sciences 16:681-735.

Dunbar, R. I. M., A. Clark, and N. L. Hur st

1995 Conflict and Cooperat i on among the Vikings: Cont i ngent Behavioural

Decisions. Ethology and Sociobiology, in press.

Firth, R., ed.

1956 Two Studies of Kinship in London. London: Athlone Press.

Fischer, C. S.

1982 To Dwell among Friends: Personal Networks in Town and City. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Foley, R., and P. C. Lee

1989 Finite Social Space, Evol ut i onary Pat hways and Reconstructing

Homi ni d Behavior. Science 243:901-906.

Foot, H. C., A. J. Chapman, and J. R. Smith

1980 Friendship and Social Relations in Children. New York: Wiley.

Hames, R. B.

1979 Relatedness and Interaction among the Ye' kwana: a Prel i mi nary Anal y-

sis. In Evolutionary Biology and Human Social Behavior, N. A. Chagnon and

W. Irons, eds. Pp. 238-249. Nort h Scituate, Massachusetts: Duxbur y Press.

Kinship and Network Size 289

Hays, R. B., and D. Oxley

1986 Social Net wor k Devel opment and Functioning duri ng a Lifetime Tran-

sition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 50:305-313.

Hughes, A.

1988 Evolution and Human Kinship. Oxford: Oxford Uni versi t y Press.

Keesing, R. M.

1975 Kin Groups and Social Structure. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Killworth, P. D., H. R. Bernard, and C. McCart y

1984 Measuri ng Patterns of Acquaintanceship. Current Anthropology

25:391-397.

Knoke, D., and J. H. Kuklinski

1982 Network Analysis. Beverly Hills, California: Sage.

Kudo, H., S. Bloom, and R. I. M. Dunbar

1995 Neocort ex as a Constraint on Social Net wor k Size in Primates. Sub-

mi t t ed to Behaviour.

Larson, R. W., and N. Bradney

1988 Precious Moment s wi t h Family Members and Friends. In Families and

Social Networks, R. M. Milardo, ed. Pp. 107-126. Newbur y Park, California:

Sage Publications.

Levinger, G., and A. C. Levinger

1986 The Temporal Course of Relationships and Devel opment . In Relation-

ships and Development, W. W. Har t up and Z. Rubin, eds. Pp. 111-133. Lon-

don: LEA Press.

Levi-Strauss, C.

1969 The Elementary Structures of Kinship. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode.

McCannell, K.

1988 Social Net works and the Transition to Mot herhood. In Families and

Social Networks, R. M. Milardo, ed. Pp. 83-106. Newbur y Park, California:

Sage Publications.

Milardo, R. M.

1988 Families and Social Net works: An Over vi ew of Theory and Met hodol -

ogy. In Families and Social Networks, R. M. Milardo, ed. Pp. 13-47. Newbur y

Park, California: Sage Publications.

Milardo, R., ed.

1988 Families and Social Networks. Newbur y Park, California: Sage Publications.

Mitchell, J. C.

1969 The Concept and Use of Social Net works. In Social Networks in Urban

Situations, J. C. Mitchell, ed. Pp. 1-50. Manchester, England: Manchest er

University Press

Mitchell, J. C., ed.

1969 Social Networks in Urban Situations. Manchester, England: Manchest er

University Press.

Rands, M.

1988 Changes in Social Net works following Marital Separation and Divorce.

In Families and Social Networks, R. M. Milardo, ed. Pp. 127-146. Newbur y

Park, California: Sage Publications.

290 Human Nature, Vol. 6, No. 3, 1995

Rodseth, L., R. W. Wrangham, A. M. Harrigan, and B. B. Smuts

1991 The Human Community as a Primate Society. Current Anthropology

32:221-255.

Thorne, B.

I986 Girls and Boys Toget her. . ~ But Mostly Apart: Gender Arrangements

in Elementary Schools. In Relationships and Development, W. W. Hartup and

Z. Rubin, eds. London: LEA Press.

Young, M., and R Willmott

1957 Family and Kinship in East London. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Adults, Brothers KeepersDocumento35 pagineAdults, Brothers KeepersChristine BlossomNessuna valutazione finora

- Nickolas A Christakis and James H Fowler 2009 Conn PDFDocumento4 pagineNickolas A Christakis and James H Fowler 2009 Conn PDFAna MariaNessuna valutazione finora

- Liliana Sousa: Building On Personal Networks When Intervening With Multi-Problem Poor FamiliesDocumento18 pagineLiliana Sousa: Building On Personal Networks When Intervening With Multi-Problem Poor FamiliesPamela Cortés PeñaNessuna valutazione finora

- Contact and InfluenceDocumento47 pagineContact and InfluenceXavi Nueno GuitartNessuna valutazione finora

- Dimensi Trust2 RidingDocumento25 pagineDimensi Trust2 RidingOlivia Barcelona NstNessuna valutazione finora

- Wrzus Social Network Changes and Life Events Across The Life Span A Meta-Analysis. Psychological BulleDocumento28 pagineWrzus Social Network Changes and Life Events Across The Life Span A Meta-Analysis. Psychological BulleCengizhan ErNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Networks Key to Unemployment ExitDocumento47 pagineSocial Networks Key to Unemployment ExitMirela PopescuNessuna valutazione finora

- This Content Downloaded From 54.252.69.139 On Sun, 13 Nov 2022 16:34:16 UTCDocumento27 pagineThis Content Downloaded From 54.252.69.139 On Sun, 13 Nov 2022 16:34:16 UTCAngel Karl SerranoNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Capital TheoryDocumento7 pagineSocial Capital TheorySittie Hadjirah Tan Baser100% (1)

- Sense of Community A Definition and TheoryDocumento19 pagineSense of Community A Definition and TheoryGummo bfsNessuna valutazione finora

- Rosander and ErikssonDocumento9 pagineRosander and ErikssonJessica Emma HeidrichNessuna valutazione finora

- Community Psychology A FutureDocumento26 pagineCommunity Psychology A FutureIsrida Yul ArifianaNessuna valutazione finora

- Beyond The Individual: Evidence Linking Neighborhood Trust and Social Isolation Among Community-Dwelling Older AdultsDocumento18 pagineBeyond The Individual: Evidence Linking Neighborhood Trust and Social Isolation Among Community-Dwelling Older AdultsAdriana SerenoNessuna valutazione finora

- Wellman - 1999 - From Little Boxes To Loosely-Bounded Networks The Privatization and Domestication of CommunityDocumento17 pagineWellman - 1999 - From Little Boxes To Loosely-Bounded Networks The Privatization and Domestication of CommunityJoana AlbinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Network TheoryDocumento17 pagineSocial Network TheoryMary Aileen Del FonsoNessuna valutazione finora

- 3.7 Fictive Kinship and Acquaintance Networks PDFDocumento14 pagine3.7 Fictive Kinship and Acquaintance Networks PDFchrisr310Nessuna valutazione finora

- Uzma - UK Draft 2Documento5 pagineUzma - UK Draft 2Vikas KhannaNessuna valutazione finora

- Problems in Cross-Cultural Contact: A Literature Review: International Journal of Intercultural Relations December 1979Documento46 pagineProblems in Cross-Cultural Contact: A Literature Review: International Journal of Intercultural Relations December 1979Teaching Department2Nessuna valutazione finora

- 9 AshkanasyEtAlDocumento18 pagine9 AshkanasyEtAlFadli NoorNessuna valutazione finora

- Helping Behavior in Rural and Urban Environments A Meta-Analysis.Documento11 pagineHelping Behavior in Rural and Urban Environments A Meta-Analysis.ericjimenezNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Network 35208 - Chapter1 PDFDocumento30 pagineSocial Network 35208 - Chapter1 PDFindusmathyNessuna valutazione finora

- Aislamiento Social en Estados Unidos Cambios en Las Redes de Debate A Lo Largo de Dos DécadasDocumento29 pagineAislamiento Social en Estados Unidos Cambios en Las Redes de Debate A Lo Largo de Dos DécadasIVAN DARIO RODRIGUEZ SALAMANCANessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study Psy 156Documento26 pagineCase Study Psy 156Ashley KateNessuna valutazione finora

- The Health-Related Functions of Social SupportDocumento26 pagineThe Health-Related Functions of Social SupportMónica MartínezNessuna valutazione finora

- Lochner Et Al 1999-Social Capital A Guide To Its MeasurementDocumento12 pagineLochner Et Al 1999-Social Capital A Guide To Its MeasurementKumar SaurabhNessuna valutazione finora

- Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences 2006, Vol.Documento8 pagineJournal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences 2006, Vol.ManolitaNessuna valutazione finora

- Gossip - Identifying Central Individuals in A SociaDocumento47 pagineGossip - Identifying Central Individuals in A SociakalipeirojohnatanNessuna valutazione finora

- Ug Dissertation NewDocumento52 pagineUg Dissertation Newkavitha_0608Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sentido de ComunidadDocumento12 pagineSentido de ComunidadPaula Andrea Tamayo MontoyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Moore, Gwen (1990) Structural Determinants of Men's and Women's Personal NetworksDocumento11 pagineMoore, Gwen (1990) Structural Determinants of Men's and Women's Personal NetworksAndrei MosanuNessuna valutazione finora

- The Role of Culture and Personality in Choice of Con Ict Management StrategyDocumento25 pagineThe Role of Culture and Personality in Choice of Con Ict Management StrategyKhup GuiteNessuna valutazione finora

- Class Contingencies in Networks of Care For School-Aged ChildrenDocumento57 pagineClass Contingencies in Networks of Care For School-Aged ChildrenvsudhakarvNessuna valutazione finora

- English 102 Research Paper - The Power of Human ConnectionDocumento9 pagineEnglish 102 Research Paper - The Power of Human Connectionapi-561964039Nessuna valutazione finora

- 04 Levine Et Al 2001 Cross-Cultural Differences in Helping StrangersDocumento18 pagine04 Levine Et Al 2001 Cross-Cultural Differences in Helping StrangersFrancis Gladstone-QuintupletNessuna valutazione finora

- Draft: Handbook of Human-Computer Interaction, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc. Publishers. Mahwah: NJDocumento63 pagineDraft: Handbook of Human-Computer Interaction, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc. Publishers. Mahwah: NJfreeman84Nessuna valutazione finora

- Why Do People Sacrifice For Their Nations by Paul SternDocumento20 pagineWhy Do People Sacrifice For Their Nations by Paul SternEllaineNessuna valutazione finora

- Example Research Paper On GangsDocumento8 pagineExample Research Paper On Gangsjhwmemrhf100% (1)

- Cultural Evolution of Human Cooperation - Richerson 2003Documento32 pagineCultural Evolution of Human Cooperation - Richerson 2003BiosLogus - Desenvolvimento PessoalNessuna valutazione finora

- Beggar EducationDocumento24 pagineBeggar EducationElizabethan VictoriaNessuna valutazione finora

- Activity in Social Media and Intimacy in Social R - 2018 - Computers in Human BeDocumento9 pagineActivity in Social Media and Intimacy in Social R - 2018 - Computers in Human BetonytocamusicNessuna valutazione finora

- Nasionalisme, Patriotisme, Dan Kelompok Loyalitas: Sebuah Perspektif Psikologi SosialDocumento9 pagineNasionalisme, Patriotisme, Dan Kelompok Loyalitas: Sebuah Perspektif Psikologi SosialArif PurnomoNessuna valutazione finora

- Pathways To HappinessDocumento12 paginePathways To HappinessCornelNessuna valutazione finora

- Thesis Statement On Street GangsDocumento5 pagineThesis Statement On Street Gangsafloaaffbkmmbx100% (1)

- Analyzing social networks and relationshipsDocumento13 pagineAnalyzing social networks and relationshipsCharlene Mizuki100% (1)

- Desde El Aislamiento A La Comunidad Una IntervencionDocumento20 pagineDesde El Aislamiento A La Comunidad Una IntervencionSamuel Fuentealba PerezNessuna valutazione finora

- Nationalism, Patriotism, and Group LoyaltyDocumento27 pagineNationalism, Patriotism, and Group Loyaltyhi thereNessuna valutazione finora

- Triangulatingthe SelfDocumento25 pagineTriangulatingthe SelfSara MohmandNessuna valutazione finora

- Role of Members in CommunityDocumento11 pagineRole of Members in CommunityHANNAH LOUISE CODILLANessuna valutazione finora

- Formal Organization, Dimensions of AnalysisDocumento13 pagineFormal Organization, Dimensions of AnalysisFernando PouyNessuna valutazione finora

- Media Theory Contributions To An Understanding of American Mass CommunicationsDocumento22 pagineMedia Theory Contributions To An Understanding of American Mass CommunicationsAna MiNessuna valutazione finora

- Coping With Loneliness in Old Age. A Cross-Cultural ComparisonDocumento14 pagineCoping With Loneliness in Old Age. A Cross-Cultural ComparisonSunt TweNessuna valutazione finora

- Socialmediaandmourning SarahbutcherDocumento18 pagineSocialmediaandmourning Sarahbutcherapi-297286213Nessuna valutazione finora

- McNamee 1996 Therapy and IdentityDocumento16 pagineMcNamee 1996 Therapy and IdentityPsic Karina BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Network Analysis ViewsDocumento13 pagineSocial Network Analysis Viewswendell_chaNessuna valutazione finora

- EJH - 15-2 - A2 - v02 (52) - Community Policing - Exploring Homelessness Through A Community LenseDocumento28 pagineEJH - 15-2 - A2 - v02 (52) - Community Policing - Exploring Homelessness Through A Community LenseAdrian WhyattNessuna valutazione finora

- Pettigrew - A Meta-Analytic Test of Intergroup Contact Theory - IRGPDocumento33 paginePettigrew - A Meta-Analytic Test of Intergroup Contact Theory - IRGPEvgeniVarshaverNessuna valutazione finora

- Document PDFDocumento34 pagineDocument PDFOscar Iván Negrete RodríguezNessuna valutazione finora

- UCSP Week 5Documento6 pagineUCSP Week 5Zach BalballegoNessuna valutazione finora

- Family, Law, and Community: Supporting the CovenantDa EverandFamily, Law, and Community: Supporting the CovenantNessuna valutazione finora

- Nguyen Masters ThesisDocumento95 pagineNguyen Masters ThesisKavirm35Nessuna valutazione finora

- Nutrients: Impact of Nuun Electrolyte Tablets On Fluid Balance in Active Men and WomenDocumento11 pagineNutrients: Impact of Nuun Electrolyte Tablets On Fluid Balance in Active Men and WomenKavirm35Nessuna valutazione finora

- Medical Students' Educational Strategies in An Environment of Prestige Hierarchies of Specialties and DiseasesDocumento17 pagineMedical Students' Educational Strategies in An Environment of Prestige Hierarchies of Specialties and DiseasesKavirm35Nessuna valutazione finora

- Model Biomedical Technician TrainingDocumento95 pagineModel Biomedical Technician TrainingafzaluddinNessuna valutazione finora

- Ebook PDF 2Documento17 pagineEbook PDF 2Sobol93Nessuna valutazione finora

- Culture, Medicine and Psychiao T: 16:287-310, 1992. © 1992 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed Hi The NetherlandsDocumento24 pagineCulture, Medicine and Psychiao T: 16:287-310, 1992. © 1992 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed Hi The NetherlandsKavirm35Nessuna valutazione finora

- Gender Body OFDocumento23 pagineGender Body OFKavirm35Nessuna valutazione finora

- Biomedical Equipment Technology Program - Curriculum - MedisendDocumento15 pagineBiomedical Equipment Technology Program - Curriculum - MedisendMahmoud Abdel SalamNessuna valutazione finora

- Cosmetics: What Makes Indian Women Look Older-An Exploratory Study On Facial Skin FeaturesDocumento15 pagineCosmetics: What Makes Indian Women Look Older-An Exploratory Study On Facial Skin FeaturesKavirm35Nessuna valutazione finora

- TestDocumento1 paginaTestjkwascomNessuna valutazione finora

- Franz Bardon PME 2001 Merkur Edition Without Part IIIDocumento371 pagineFranz Bardon PME 2001 Merkur Edition Without Part IIIeverquest100% (5)

- Ebook PDF 2Documento17 pagineEbook PDF 2Sobol93Nessuna valutazione finora

- 2012 Past Years OSCE AnswersDocumento30 pagine2012 Past Years OSCE AnswerschristietwongNessuna valutazione finora

- Edward Bernays - PropagandaDocumento79 pagineEdward Bernays - PropagandaAdil Tahir100% (1)

- Is Magic Possible Within A Quantum Mechanics FrameworkDocumento28 pagineIs Magic Possible Within A Quantum Mechanics FrameworkRex AeternusNessuna valutazione finora

- Survival Guide 08Documento172 pagineSurvival Guide 08Kavirm35Nessuna valutazione finora

- PT Guide To Achon Spinal Stenosis - ain.JHUDocumento3 paginePT Guide To Achon Spinal Stenosis - ain.JHUKavirm35Nessuna valutazione finora

- Skin InfectionsDocumento2 pagineSkin InfectionsKavirm35Nessuna valutazione finora

- Practice GuidelinesDocumento11 paginePractice GuidelinesMohammed AbdAllah Elsayed DessokyNessuna valutazione finora

- Vascular TraumaDocumento7 pagineVascular TraumaKavirm35Nessuna valutazione finora

- Q1W3 Personal DevelopmentDocumento32 pagineQ1W3 Personal DevelopmentLD 07Nessuna valutazione finora

- M Atthew Arnold "The Function O F Criticism at The Present Tim E" (1864)Documento3 pagineM Atthew Arnold "The Function O F Criticism at The Present Tim E" (1864)Andrei RaduNessuna valutazione finora

- Annual Report 2015Documento31 pagineAnnual Report 2015Nigel CabreraNessuna valutazione finora

- Final Exam Questions on Teacher and School CurriculumDocumento3 pagineFinal Exam Questions on Teacher and School CurriculumJan CjNessuna valutazione finora

- The Asian ESP Journal: June 2019 Volume 15, Issue 1.2Documento429 pagineThe Asian ESP Journal: June 2019 Volume 15, Issue 1.2Abner BaquilidNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 9. Choosing A Career (1) : OpportunityDocumento7 pagineUnit 9. Choosing A Career (1) : OpportunityNguyễn ThảoNessuna valutazione finora

- Calcutta Psychology Department ProfileDocumento42 pagineCalcutta Psychology Department ProfileSamim ParvezNessuna valutazione finora

- Paganism & Vitalism in Knut Hamsun & D. H. Lawrence: by Robert SteuckersDocumento7 paginePaganism & Vitalism in Knut Hamsun & D. H. Lawrence: by Robert Steuckersben amor faouziNessuna valutazione finora

- The Adventures in Harmony CourseDocumento183 pagineThe Adventures in Harmony CourseSeth Sulman100% (10)

- 3is QUARTER 3 WEEK1Documento5 pagine3is QUARTER 3 WEEK1Monique BusranNessuna valutazione finora

- Prometric Electronic Examination Tutorial Demo: Click On The 'Next' Button To ContinueDocumento5 paginePrometric Electronic Examination Tutorial Demo: Click On The 'Next' Button To ContinueNaveed RazaqNessuna valutazione finora

- The Importance of English Language in MalaysiaDocumento6 pagineThe Importance of English Language in MalaysiaMohd Redzuan Rosbi BasirNessuna valutazione finora

- AIFF Coaching Courses GuideDocumento15 pagineAIFF Coaching Courses GuideAjay A KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- SyllabusDocumento1 paginaSyllabusapi-265062685Nessuna valutazione finora

- Dms-Mba Data Analytics-SyllabusDocumento103 pagineDms-Mba Data Analytics-SyllabuskjigNessuna valutazione finora

- Annual Gender and Development (Gad) Accomplishment ReportDocumento4 pagineAnnual Gender and Development (Gad) Accomplishment ReportRoxanne PaculdarNessuna valutazione finora

- Development Methods and Approaches: Critical ReflectionsDocumento303 pagineDevelopment Methods and Approaches: Critical ReflectionsOxfamNessuna valutazione finora

- CN4227R - Course Outline - 2015Documento11 pagineCN4227R - Course Outline - 2015TimothyYeoNessuna valutazione finora

- NUML Rawalpindi COAL Assignment 1Documento2 pagineNUML Rawalpindi COAL Assignment 1Abdullah KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Victor Mejia ResumeDocumento1 paginaVictor Mejia Resumeapi-510300922Nessuna valutazione finora

- Las Tle Smaw q3-w7-9Documento11 pagineLas Tle Smaw q3-w7-9Daryl TesoroNessuna valutazione finora

- Beta Blue Foundation Marketing InternshipDocumento2 pagineBeta Blue Foundation Marketing Internshipanjali singhNessuna valutazione finora

- Knowledge, Attitude of Sikkim Primary School Teachers About Paediatric Hearing LossDocumento6 pagineKnowledge, Attitude of Sikkim Primary School Teachers About Paediatric Hearing LossMaria P12Nessuna valutazione finora

- November 2019 Nursing Board Exam Results (I-QDocumento1 paginaNovember 2019 Nursing Board Exam Results (I-QAraw GabiNessuna valutazione finora

- Cycle Test 2 SyllabusDocumento1 paginaCycle Test 2 Syllabussourabh224Nessuna valutazione finora

- School Form 2 (SF 2)Documento4 pagineSchool Form 2 (SF 2)Michael Fernandez ArevaloNessuna valutazione finora

- Beach and Pedersen (2019) Process Tracing Methods. 2nd EditionDocumento330 pagineBeach and Pedersen (2019) Process Tracing Methods. 2nd EditionLuis Aguila71% (7)

- Containing Conflict and Transcending Eth PDFDocumento27 pagineContaining Conflict and Transcending Eth PDFkhaw amreenNessuna valutazione finora

- Akhilesh Hall Ticket PDFDocumento1 paginaAkhilesh Hall Ticket PDFNeemanthNessuna valutazione finora