Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Ritual by Cirilo F

Caricato da

marielsalgoDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Ritual by Cirilo F

Caricato da

marielsalgoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Ritual by Cirilo F. Bautista is about a man who has demonic power.

In 1971, the

short story won first prize in the Carlos Palanca Memorial Awards for

Literature.

In the mountains, they call it Going Beyond.The way they pronounce the Words endows the

sound with a hushed finality as though the meaning had nothing to do with the syllables,

the lips just a bit parted, afraid to release The Words altogether.The head is bowed during

the utterance, signifying both the solemnity and the apocalyptic nature of the occasion.If

you had been there then you would have see how the men, baskets of cabbages and green

bananas on their backs, would meet on the muddy trail and whisper to each other.You

would have understood from the contour of their lips that The Words were said; and these

having been said, they would pursue their individual ways--one, perhaps, to wend his way

to the Market, the other to wait by the Highway for Tourists to purchase his vegetables at a

pauper's price.Women sitting on the cold bamboo benches before the village store would

suddenly interrupt their conversation by an ominous silence:you knew they were thinking of

The Words; they did not have to say them.In fact saying them would be only anti-climactic,

because deep in their minds lurked images that could not be collapsed into a mere couple of

sounds.A father queried about the whereabouts of his son would whisper The Words, raising

him arms in the direction of the Mountains, and you would be a Fool if you thought he

meant his son had gone away to live in another place.The raising of arms is supplementary

to the meaning of the Words, at times it means more than The Words."He's gone beyond,"

the father would say."No, he's not dead, but he's gone beyond."Beyond is more than the

physical boundaries of the Village, more than the physical boundaries of the Mountains,

more than the Sea and the Sky and the Land put together.Yes.It is not Death.It is not Life.It

is not Life and Death put together.You may give it any name you want, you may declare the

people mad, but in the Mountains, they call it Going Beyond.

"The trouble with you," Roy said, "is that you are a coward."

I looked at him framed by the last glow of sunset that managed to pour through the misted

windowglass.He had just arrived from the City which, from the vantage point of this far-

flung [sic] Village, was on the other side of eternity.His single bag ("I like to travel light")

lay beneath the army cot that stood parallel to the wall; this and the other on e I called

mine touched ends to form an ell, with the two windows dotting their extremities.It was a

small room, though it was room enough for me.Even in the rare event when I had an

overnight visitor there was still sufficient space to spare.

"The trouble with you is that you are a coward," he said again turning to me after quaffing

the last drops of his drink."Imagine coming here, living here with God knows what kind of

people.This is not the place for you."

He walked to the table in the middle of the room to refill his glass; the moment he was

embraced by the light, the single light that dangled from a single cord from the ceiling, I

saw that the years had not altered him.I do not mean that he had not grown old; I mean

that his soul had not changed:he was still Roy, my big brother, my friend trying to save me

from distress most of which he had only imagined.Or I may be wrong.Perhaps he had

changed, only I was too ensconced in my new world to notice the realities outside it.

"How's Luisa?" I said.I had not moved from sitting on my cot.

"She's going to have a baby.You cannot expect a woman like her to remain alone forever,"

Roy said.

"And the man"

"She can't ask for anyone better."

"I'm glad she's happy."

"It's not a question of happiness," he said moving back to the window."A lot of

people die not knowing they are happy.It's a question of knowing someone is there for you

to turn to when you get sick of being with yourself or punching the same infernal machine

day in and day out."

"I did my best," I said, but my mind was groping for some more definite words.

"You did what you thought you had to do.As to whether that was the right thing to

do"

He respected my feeling.That one thing kept our friendship alive; I could not help

thinking, however, that the sentence would have ended with an undertone of reproach.

"You kept away, for sure," he said, "and I must say you did it magnificently."It came

at last.He swept the room with a wide gesture of his arm, a gesture that encompassed also

the whole Village."But I came not to speak about that.I know you don't want to speak about

that.I came"

"Yes, why did you come?"

He was silent for a moment.Then he said, "Come to think of it now, I don't know hwy

I came I wanted to see you.It has been two years after all."

Two years! How could two years have passed?Probably the Mountains had something

to do with it:Time that ordinarily knocked on the doors in the City, that pushed one to work

and back to home again, Time that stole but never gave, was here a non-entity, or, at

most, an ignored presence:the Mountains leveled [sic] it, the winding roads and the cool

trees tempered it, so that when it finally arrived at the doorstep, it was all haggard and

hungry and begging for a lodging.As to what tow years had done to me I did not know;

when you do not bother time it stays away from the fringes of your memory and comes to

you only in the guise of images not brilliant in their broken-ness, which you can easily push

into that cave of darkness called the Mind; the Mind, no more than Time, reposes when the

muscles repose:both speak the same language.

Two years.This morning I received a letter from Dayleg, the import of which struck

me only when I came to the last passage.Dayleg of the dikes and the downy cogon grass,

Dayleg of the dancing uninhibited, Dayleg the devotee turned defiant, Dayleg of the broken

skin and white teeth, had spoken at last.Remember the hunt we had two years ago, he

wrote, how we crossed the line between heaven and hell in pursuit of the white boar?I

remembered.The sacred grove was hardly a forbidding sight:it was like any mountain

hunting ground, though there was a sharp tang in the air while the frail twigs crackled

louder as we stepped in between the willows and the pines.But then perhaps we really were

just half-aware of these, our senses attuned only to the presence of the quarry.

"Father says this place is a thousand years old," Dayleg said."By the way we are

trampling all over it we deserve at least fifty years in Hell."

"You can start your penance now," I said, "Surely the gods will accept contrition by

installment."

"Its down by the stream.Let's encircle it."

The profound significance of the moment sprang before me while I moved as Dayleg

directed.We were on forbidden grounds tracking an equally forbidden animal.The fact that I

was an outsider did not alter nor lighten the gravity of my involvement.Even as we were

encircling the animal a network of guilt was weaving tiny holes of pain in my conscience.By

consenting to the hunt I was sharing in the malevolence of a conspiracy.

When I arrived by the stream Dayleg was already bending over the dead animal.A

single arrowtail protruded form one side of its neck, the arrowhead having shot clean

through the other side.

"It's not white after all."Dayleg was disappointed."They had always told me it was

pure as the clouds."

"What shall we do with it now?" I said, eyeing the animal.It was about three feet

long, its body covered with thick grizzly hair; mud and blood glistened round its throat.Its

tow tusks were ivory in the fading light.In cold repose the boar seemed to cling to its mythic

holiness as long as it could.

"We'll bring it to the village and show the elders the lie they've been handling us all

this time."

By the light of the fire we had built against the cold I could see Dayleg's face as he

spoke.It had turned bronze; his eyes shone as though relishing the wickedness of what he

had planned to do.His dark slender trunk covered with a dirty G-string was damp with

sweat.

But wouldnt that be the height of sacrilege?You asked.You could not hide the shock

(or was it fear) in your face.I could not understand your concern for thewhole thing.All you

had to do was pack up and go.The gods would have a hard time finding you in the city,

crude and walking as they are, if ever they have the mind to meddle in the affairs of a

foreigner.Their sovereignty is confined to the mountains.

The mountains swelled in darkness as we started our descent to the Village.Dayleg,

his sturdy legs punching the sward, the sacred boar stradding his neck, moved easily down

the mountain side while I picked my way, stumbling now and then on the rocks or slipping

down the moist grass.

The cat would eat fyshe but he will not weate his feate.

What?I said. I could barely catch up with his steps.

English proverb, he said.A lot of them in the books.Very good for the mind.

We walked in silence most of the time.In spite of the cold night, perspiration soaked my

clothes. The knapsack grew heavy on my back.I wiped my face with the sleeve of my shirt.A

true son of the mountains, Dayleg never slowed his pace but even whistled once in a

while.Looking at him naked save for a piece of loin-cloth I could hardly believe that he was

one of the most intelligent men I had met. When first I came to the Village, the first person

I saw was a young native squatting by the roadside and cleaning the tip of a ten-foot

spear.The spear was common sight in the place, I had been told earlier, for it was both a

means of tilling the soil and, during a tribal feud, of disemboweling the enemies.Occupied

by what he was doing, he hardly responded when I asked him for directions to the village

school.But the word school made him raise his head.He surveyed me from head to foot

before giving me the directions I wanted.

The school was a four-room structure of wood and galvanized iron located in a small piece

of flat land the people called The Valley. Big pine trees that protected the structure from

both sun and wind gave it a quality of idyllic serenity usually associated with

monasteries.You climbed three steps to find yourself in a kind of balcony that overlooked

the whole schoolground.

Of course one can get terribly lonely here, and one usually does, the Principal,

father Van Noort from Belgium, said.I had knocked on the door of his office at the back of

the school building and was met by an old man with graying hair and a brownish soutane

that used to be white.Like most of the missionaries I knew, he had a fondness for native

cigars.The office was a small room in which were miraculously accommodated a roll-top

table, a rattan chair, a wooden bed with a feather mattress, a table with several dirty pieces

of cutlery, two chairs to the table, bookshelves, books, wastecans, a table lamp, the

sculpted figure of a mountain warrior holding the severed head of his enemy in one hand

and his sword in the other.

Father Van Noort brushed the ashes form his sleeves.As I mentioned in my letter,

youll be in charge of the fifth class.Literature and language.

There was a knock on the door followed by the entrance of a dark-skinned man

carrying several books.His white trousers and white shirt were spotless; the electric bulb

was reflected on his shoes.

Carlos Dayleg, in charge of the fourth class, father van Noort said to me by way of

introducing the newcomer.

I think weve already met, Dayleg said, extending his hand.It was only then that I

realized he was the man I asked directions from a few hours ago.He must have noticed my

surprise.Yes, we met this morning. In this place it is not uncommon for natives to change

to more civilized attires.As for me, I do it only on special occasion.

And school is a special occasion, Father Van Noort said.

And school is a special occasion, Dayleg said, and going to the movies and visiting

the Mayor,

After classes Dayleg invited me for a drink.A few minutes walk from school, down

winding paths that led past the native huts squatting on hard-packed mud, past the curious

structure of a cogon roof placed right on the hard-packed mud, the remains of a bonfire in

the very center of the space which one could enter only by crawling on all fours, past this

nest of love by t4rial, past half-carved coffins drying ion the sun, emerged Daylegs hut.We

climbed a steep ladder to the center of the room.

Make yourself comfortable, Dayleg said.The old man must be in a feast

somewhere.The clang of brass gongs filled the hut, reverberated against the rafters,

seemed to seep down through the bamboo floorings and settled on the ground

below.Dayleg took an earthen jar form a corner. He placed two plastic glasses on the low

table.With a groan he sat down beside me.The heat of the rice wine snaked through my

throat that was the first time I ever drank it, and the taste was both strange and

sweet.Here we ferment rice into wine, Dayleg said.The longer, the better.Of course if you

overdo it you get vinegar.

That night we talked about many things.I learned that Dayleg had finished a course

in pedagogy and philosophy in a university in the City, and that he had come back to his

village to do his part in the education of my people.But the rest of our talk came to me

now in images and impressions that flitted in my brain like cinematic associations, the focus

always changing.A jar of rice wine does so much to blur the memory, though the pictures

are nevertheless recognizable:Dayleg, sixteen years old, sitting before the Council of Elders,

being reprimanded for shouting at the village High Priest; the smell of pig roasting, its

smoke wafted through the pores of houses, everyone poking his head through the window,

straining to smell the meat and to hear the familiar sounds, for this feast was for Lumawig,

He Who Sends Fruition to the Earth, the men and the women woven into a circle, the fire in

the center, swinging to the rhythm of the gongs which constant use turned golden, like the

bright deathmasks of ancient mummery, dancing and chanting, amongst them Dayleg

handsome in his nakedness; the circle widening with the shouts of combat, in the center

Dayleg with a spear in a stance of sciamachy, fearless as a man for whom death had no

meaning, resolved only to redeem the honor of his tribe while the circle metamorphosed

into many pointed lances; Dayleg alone in the spot, a bloody wound in his thigh, the circle

broken; myself with eyes bloodshot pouring wine into my twenty mouths when Dayleg

tipped the jar and the floor bloomed into a hundred wet pieces of clay; a graduation

photograph left to right, third row Manuel Pantig, Jose Arcana, Roberto Galdon, Lauro

Canlas, Antonio Morte, Lorenzo Peron, Carlos Dayleg, Mario Tarsus; a dark face lined with

the furrows of years, saying Hardly were the feet cold that followed your mothers coffin

than you should break her jar.Aie, I tell you, Son, this house will know peace no more!, the

clash of cymbals in a nameless place as warriors without faces whirled up and down in air

till one of them, naked, plunged backward shattering his spine against a giant monolith.

Its not because my people are uneducated that they cling to ancient tradition,

Dayleg said as we walked around the schoolyard during recess the next day, but its a

reason civilized men like you dont and cant fully understand.Ars longa, vita brevis, as

your philosophers say, yet something longer than art governs the very consciousness of

these people.It goes to the very bone of their existence. Lumawig, Creator of Earth,

permeates their lives, my life, and these traditions are but extensions of His Being. When

one turns his back on these he forfeits glory in the afterlife.

Then youve already lost a great part of that glory, I said reminding of the wine

jar.That is pardonable under the circumstances in which I broke it, he said.He shrugged

off the matter.But what must be obvious to you is that I do things to break these

traditions.I believe its about time some of them were challenged.

I could hardly understand him for the contradictions in what he said; perhaps he was

not aware of them, but on my part the more I got to know him the more complex he

became, until an incident that disturbed the elders provided me with the first insight into his

character.

He had gathered thirty of the old villagers, marched them to the schoolhouse where

before the blackboard topped by a picture of a severe unsmiling Rizal he lectured them on

the advantages of forsaking Lumawig and adopting the ways of the Christians.His listeners

sat with the passivity of a people used to the hard exigencies of mountain life, their faces

stolid as the rocks the school was perched on, neither nodding nor shaking their heads, for

they could not follow the ramifications of this strange exotic dialectics, taking the words

more out of respect for this young man who had been to the university than out of interest

for what eh was saying; a few of them appeared confused, who had come only thinking

there would be planning a foot for a forthcoming feast.While he was heading toward the

school.His father strode into the room with his army boots clacking on the loose floor boards

followed by ten of the village elders.Surprise and anger were written on their faces.They

surrounded him with the combined smell of sweat, tobacco, dust and breath the basic

ingredients that had kept these people alive in this remote chunk of earth.

Know what you're doing? his father said in his face. He raised his arm as if to strike

his son, but it fell limply on his side.

The devil has charmed his tongue, one of the elders said.

And his eyes, another said.

I can do what I like, Dayleg said.

To make your mother turn in her grave?

To bring my people light.

It has not fallen upon your shoulders.

Thats what I went to school for.

You are young, a white-haired elder said, obviously the leader.We can still forgive

you.

I dont see anything for you to forgive, there was recussancy in Daylegs words.

Stung by this insolence, the leader turned to his companions.

There is no question but that we should hold a council, he said.The rest of you go

back to your work.With a last glance at Dayleg he led the group out of the room.

The Council, of course, condemned Daylegs action; it ordered him to refrain, under

pain of expulsion from the tribe, from expounding foreign philosophy to the natives.If

Dayleg was hurt by this decision he did not show it.He was one who would not make a

martyr of himself even though martyrdom danced before his very eyes.Consequently, there

was a change in the peoples attitude toward him:they were more careful in mentioning his

name.They did not avoid him outright though they took the precaution of not being seen

talking to him.

When we reached the Village, it was midnight.Arriving at his fathers house, Dayleg

groped in the darkness under it looking for a suitable depository for the boar while I sat on

an old tree stump to catch my breath.The moon had come out form a layer of clouds to

provide the only illumination in the place, the big, pot-bellied moon which on other nights I

might have found romantic but which now enwrapped me with a feeling of dread.

Tomorrow we hold the sacrifice, Dayleg said sitting beside me.We sat in silence.I

listened to the shadows moving across the houses, listened so hard that after they had

vanished with the moon that sailed right through the door of the sky I was afraid, to say the

least, and was now beginning to shiver from the cold and from hunger.When I turned to

Dayleg I saw he was fumbling with something.

You must be hungry.Here, lets start a fire and roast some meat, he said.He had

gone up the house and secured the food without my noticing his leaving my side.The odor

of roasting whetted my appetite.He had also brought a jar wine which, together with the

meat, eased my hunger.But my muscles were still taut in tension; I was fearing some

thought that had not completely taken shape.

Dayleg ate without saying a word.Now and then he would glance under the house as

though in spite of the darkness he could see the boar, as though in spite of the darkness he

could read some cabalistic calendrics on the skull of the boar.Three school terms I had

worked with him but I knew nothing about him, except his preference for canned food, his

indifference to women, his love for the rice terraces.Not that he was reserved or aloof he

was sociable but his sociability revealed merely the outer encumbrances of his

personality, much as the sphinx revealed merely the outer characteristics of its animalism,

but the mystery that shrouded it amidst the burning desert sands few could

untangle.Perhaps the metaphor was far-fetched; perhaps he was enigmatic not because I

could not understand him but because I was analyzing him from an irrelevant angle.Luisa

had told me that I was always inclined to be a poetic.You see things only after your

imagination has colored them.You wont look at them as they are, she said.And Roy

accused me of being a poet as though that was a crime.He pointed out that poets were an

anachronism in an age of practical realists who regarded mankind with precise scientific

minds in search of solutions to its problems.Perhaps I saw Dayleg from a wrong

perspective.My own life with Luisa was an out-of-focus affair.We had known each other for

three years.She was secretary to an oil executive in the City and I was a reporter for an

afternoon paper.Because of the nature of my work I saw very little of her yes, we would

go on dates on Sundays, to the cinema, the beach, but most of the time we did not know

what the other was doing.Not that it was necessary to know that we loved each other;

sometimes, however, one needs some form of assurance that his beloved is still alive or

faithful.I guess I was the possessive type for I insisted that we got married.After all we had

been planning that for the past year, only we were afraid we could not live decently on our

meager income.I asked for a weeks leave form my editor and she did the same form her

chief.We og6t married in a simple rite with only the priest, Roy, and Blanca Luisas best

friend in attendance.After that we had an inexpensive dinner, bad Roy and Blanca good-

bye, and off we were to our honeymoon in the Mountains. It was, I can say, a happy week

we had together.Watching Luisa cook, take care of the house and attend to my needs I

thought I had found the most wonderful woman in the world.It was when we came back to

the City that life did not fulfill what it promised in eh beginning.I had wanted to be the

breadwinner in the house but Luisa did not want to give up her job.I could not accept the

knowledge that she was earning more that I was, that some other men could command and

reprimand her.Roy said this was unfair of me. You are selfish.Soon youll have children and

your wifes earnings will surely help, he said.When I told him I did not intend to have

children he said I was crazy and should not have gotten married in the first place.I admitted

that I had not given that any thought before having children and that my sole aim in

rushing Luisa into marriage was to possess her.I was jealous of any man who as much as

looked at her.Having been poor all my life, I desperately wanted something to call my own,

ye6t I was suddenly afraid to face the responsibilities of a married man.Three months after

our marriage I packed my things and headed for the Mountains after writing Luisa a

note.There I learned later that she had asked for an annulment of our marriage which the

Church granted.On what grounds I did not know, nor care. I was glad to forget my failure as

a husband.

A ripple of noise cut my sleep:the ripple became wider until I found myself sitting

greatly awake, looking around in the room.It was early morning.Dayleg was asleep in a

corner near the post. I could hear excited voices emanating from below the house:they had

discovered the boar.

Soon Dayleg too was disturbed by the noise.He sat upright, listened for a while, then

rushed out of the room.

When I got downstairs a thin blinding light pierced my eyes; momentarily I stood

there till the light flashed out of my sight.Thrice it flew up and down then ended in a silver

strip that was a machete.Dayleg was brandishing it, no, gesticulating with it as he was

confronted by the elders.A crowd had gathered near the house after someone saw the boar

and informed the elders; they came some of them still shake from interrupted sleep,

some uncertain of what the disturbance was all about more than a hundred brown and

shiny skins.Dayleg stood tall and looming over the animals as though trying to protect it

from any sudden snatcher; he held the machete high above his head, its blade pointed

upward and catching slivers of sunbeam.His face was granite, inscrutable.

The curse of gods upon us! an old woman cried.Many a year I have lived here

wishing that at my death I could see the sacred boar running.Now I see it dead.The curse of

gods upon us!She was joined in her wailing by other women who had nurtured the same

hop.The others became more excited:they pushed and jostled each other to get a better

glimpse of the animal and, when the profundity of its violation occurred to them, entered

with the women into a state of general moaning.

The grove has been defiled!

The infidel!

The village shall be without light!

A thousand droughts shall stalk the terraces!

The curse of gods upon us!

Who would believe it our own man

Somebody pushed through the thick circle of bodies and stood facing Dayleg on the

opposite side of the cabbage crate on which the boar spread, its body outlined by a pool of

coagulating blood.It was the leader of the elders.Anger that distorted his face ran through

his gleaming eyes down to his hands clenched at his sides.The crowd held its breath looking

from one man to the other.

In the name of Lumawig, why did you kill the boar? the leader said.

Ti was there for the hunting, Dayleg said.He had put down the machete on the

ground.

For the hunting of the gods, yes, but for us mortals

The gods would no more hunt there than we would hunt in the moon.

Blasphemy! the leader shook his fist at Dayleg.

The grove is not sacred.

Blasphemy!It has always been and will ever be.Lumawig himself consecrated it

when he came down to earth.

That is a lie you and the others help to perpetuate. Look at your boar!What is to

distinguish it from any other boar?Its blood is as filthy.

It is sacred, the leaders anger was mounting.

It is dead, Dayleg said with contempt in his voice.

It is sacred, the crowd, contaminated by the leaders anger, repeated.

It is dead!Dayleg shouted.Dead!He picked up the machete and poked it at the

animals belly to emphasize his words.

The old woman wailed burying her face in her hands.The curse of gods upon us!

Dayleg, the leader shrieked above the womans wailing, I tell you your mother is

turning in her coffin at the shame you have brought us.

I am no more guilty of killing this boar than you are declaring it sacred.

It is sacred! the crowd said.

It is dead, dead!Dayleg said.Only fools would cry over a stinking carcass!

Forthwith he started hacking the boar:the blows thudded on its body as again and

again the gleaming machete fell on it.The crowd watched in horror, some gasping for breath

as if their very bodies were being hit by the weapon. The womens wailing at this flagrant

destruction of the gods minion rose and fell with the rise and fall of Daylegs hand.

The demon has seized him.

Woe to our children and our childrens children.

Dayleg!In the name of Lumawig, stop it.What are you doing?

Im breaking your lie.

And consigning us all to hell?

And freeing you from blindness.

Son, stop it!Daylegs father clasped his hands imploringly.

No.The sharpness in Daylegs voice sent an icy shiver down my back. By all

indications he was mad, for he hacked the boar even as it lay almost an indescribable mass

of flesh and gore.Sweat and the animals blood that had spurted out covered his face and

arms that shone as the sun rose and struck them.As I watched him I discovered the Dayleg

I knew was not even the shadow of this one before me.

Dayleg, stop it1Its not too late.The gods can still forgive.The leader was on the

verge of tears.As against the crate he leant for support, his bony fingers were black at the

joints.

No, Dayleg said.Ill show themHe picked up a piece of the boars flesh, held it

high over his head and shouted, I curse you!

The crowd moved back terrified as the sacred blood dripped from Daylegs fingers

and the sacred flesh quivered in his hand.

Son, stop it!

In the name of Lumawig, abandon this madness!

The wrath of gods upon us!

I curse you, the sounds came from the sepulcher of Daylegs throat, by a crooked

line, a broken line, a right line, a simple lineSon, remember you mother.

by flame, by wind, by mass, by rain, by clay

Lumawig, Ruler of the Sky, the leader said kneeling on the ground and beating his

breast, forgive Your son.He is young.The heat is in his blood.

by a serpent, by a flying thing, by a creeping thing

He has sacrificed many a cow in Your honor; he has danced till his bones ached in

Your feast.

The wrath of gods upon us.

Many of the natives had also knelt; the rest, stunned by the horror, sat simply on

the ground.Dayleg alone stood before the crate, his hand still outstretched holding the

boars flesh, stood handsomely tall mouthing his antique incantation while the sun rose

higher and higher to surround his head with a crown of fierce light.

I curse you by an eye, by a hand, by a afoot, by a cross

Look not upon this day as a breach upon Your will, the leader said crying, but

close Your eyes to the wind.

by a sword, by a scourge, by a flood

The wind brings no message if You wont listen.The sun blinds You not with

horror.Let Your mind forget this day.

Haade, Mikaded, Rakeben

Lumawig, we pray You forgive Your son.Remove not your love from this people.

Rika, Ritalica, Tasarith, Modeca, Rabert!

On the last word Dayleg flung the boars flesh to the ground and overturned the

crate with a kick that spilled the rest of the carcass onto the earth.

The last pictures I bore with me that day as I left the scene of defilement were of

Dayleg overturning the crate, his chest and face and hands stained by the sacred blood,

waving the machete and uttering words I could not catch while the shrieking villagers,

afraid Dayleg would turn his passion at them, ran in terror, of the leader of elders pulling his

white hair, still kneeling in supplication to Lumawig to forgive the man who at that very

moment was desecrating the gods minion:suppliant wetting the ground with his tears, of

the sun in its apex lighting the chunks of boars flesh in harsh legs of luminance, moving

because the universe must complete its course.

Three months later, while I was in the city during the semestral vacation, I ran into

Father Van Noort; he had been on leave from school for a year now on account of his heart.

I invited him to a cup of coffee in a nearby restaurant.Except for a little paleness on his

cheeks he looked healthy; I called his attention to this and he said, I ought to be healthy.I

live in the Orders hospital, you know, and there they treat me like a kid.Diet.Exercise.I like

everything but their denying me my tobacco.Imagine doing that to a man who has all this

time subsisted on the weed!:I reminded him that it was for his own good and he shrugged

his shoulders in mock resignation.When I related what Dayleg had done to the sacred boar

he shook his head; the shadow of sadness passed across his face.

It was bound to happen, he said.Dayleg is what you may call a complex person.I

dont mean that hes schizophrenic or something, but hes not transparent either.Some

people you can read like a book, Dayleg you have to decipher.

He seems simple enough, I said.

Yes, but remember simplicity is not transparency.Beneath Daylegs tribal

accoutrement lies the tension between self and reality, a tension call it paradox if you like

which is common to persons like him.

When will this tension subside?

I dont know.Who knows?Perhaps when he finds peace.I dont know.

I dont really know why de did it, Sir, wrote Mario, my best student. His letter

reached me while I was still on vacation a few days after I met Father Van Noort.I was

there, Sir, and I cannot describe to you my feelings as I watched him destroy our sacred

boar.You may not understand it, Sir, you not being one of us, but from our birth we have

always believed that the grove is only for the gods, that whoever enters it and as much as

touches a blade of grass in it will be denied eternal happiness.I believer this, Sir, that is why

I was horrified by Mr. Daylegs action.He did not only bring shame to our village, as you will

see, Sir, when you come back.Mr. Dayleg has disappeared.It is better that he did not

witness the rites the elders held for his expulsion.Under our laws, Sir, such acts as Mr.

Dayleg committed are grievous, so the actor has to be driven out of the tribe to lessen the

gods wrath on the innocent ones who have, nevertheless, been tainted with the guilt by

their relationship with the sinner.Sir, we have to do a lot of sacrifice to wash this sin.I dont

know how this will be possible.The harvest is not good this year.But the best thing is for the

sinner, in spite of his expulsion, to come back, to show repentance.Only then will the gods

consider our prayers.But we dont know here he is.

Two years.,

I stood up and walked to the window; with my fingers I rubbed off the mist that had

collected on the glass.I peered outside.The world was a blanket of darkness.These two

years I had tried to find peace, to re-order my life toward a more meaningful goal, but

things eluded me.An indefinite fear was gnawing my mind.

Anything around here to eat?Roy shouted from the kitchen.I could hear him

opening and losing drawers.

Theres a can of beans on the upmost shelf and some meat in the bowl on the

table.Theres some rice near the stove, I said.

I smoked as I watched him eat.Outside, somewhere in one of those spare, squat

houses with roofs and walls of cogon, I knew, a group of white-haired men was praying to

the gods.In these two years that Dayleg had been gone they had not stopped their

supplication.The harvest had been regularly poor, a sure sign of the heavenly

displeasure.hes gone beyond, they would say alluding to Dayleg, the gods have turned

their faces away form us.

There had been no rain for the past three months, whereas before it came sooner

than the planting season, soaking the terraces and fattening ht frogs that croaked in the

mountain crags.Now the rice plots lay barren like a thousand mouths without blood, and

plating time was just a week ahead.Only the fog rubbed the soil and tinted it with a whiff of

wetness that was gone as soon as the fog had lifted.

And you have not seen him since?Roy said after I had told him what had

happened.

No, I said.I quenched the light of my cigarette in the metal ashtray.But I have just

received a letter form him.

Does he say where he is now?

No.The letter bears the Citys postmark.

Sounds like a strange fellow to me.

He is.I cant understand him, couldnt understand him myself.I dont think anybody

here understands him.

Maybe hes an exception to the rule.

The rule?

I mean in any society or tribe theres bound to be someone whod violate traditions

and laws.Not that hed do it for the heck of it, but that in him probably a new personality is

emerging.

I though of Father Van Noort.

A synthesis, we may say, of the old tribal character and the modern patterns that

slowly put him in a quandary:he may be alienated entirely from his native roots or he may

bridge the past with the present.

Im thinking Dayleg is an intelligent, I said.

Intelligence has nothing to do with it.Why, may I ask, did he do what you said he

did if he is intelligent?No, its a matter of blood, not of intelligence.

Well, I said, its done.His people are having a hard time appeasing the gods.And

to top it, rain has not yet come.I dont know how this people will survive a year of hunger.

Appeasing the gods by prayers?

Yes.And sacrifices.Tomorrow theyll hold a big one.Killing a cow, you know,

changing, dancing.

Thats one thing Id like to see.

Well be there.

We took another shot of whiskey before going to bed.

Early the next morning, while I was boiling some coffee, there was a knock on the

door.Roy was still curled up in his cot, so I crossed the living room to see who it was.It was

a tall dark man in dirty maong trousers and gray shirt, his hair long almost touching his

shoulders; his beard and moustache covered a large part of his face.

Yes?I said, not knowing what he wanted.

Then he uttered my name.

Its me, Dayleg, he said.

I stood there in disbelief; Dayleg.Dayleg, I said to myself.A thousand thoughts

rushed to my brain like a flood.

Its me, Dayleg, he said again when he noticed my hesitation.

I opened the door wide and he stepped inside.I led him to the kitchen just in time for

me to prevent the coffee from spilling all over the stove.

What happened? Where have you been?I could scarcely conceal my excitement.

He sat down by the table on which, so many times before, we had worked till

midnight making our lessons.He had lost weight his shirt was loose around his shoulders

and his veins stood out of the skin of his arms.

Nothing, he said. I have been living with a friend in the City.

But why didnt you tell me?I could have helped.

Nobody can help me.

Been working?

I could not though I wanted to.

You could have taught.Your record is excellent.

You dont understand, he said and looked at me with his bloodshot eyes.Its not

that.The gods.

What?I almost dropped the cup I was holding.

You received my letter?

I nodded.

Then, he continued, you know what I mean.

Vengeance?

The gods.

You knew about that before, didnt you?Even before we hunted the boar?

Yes.His voice was old, tired, excruciated by a force too strong for me to

unlock.But I didnt believe it then.

But Im not staying, he said softly.

What?Then why did you come?

To tell you good-bye and to get the things Ive left here.

You know what youre doing, of course.

Thats the only thing I can do.Ill go far enough where no one can touch me.

Perhaps, but your people will suffer in the meantime, as theyve been suffering

these past years.

They can blame the gods.

Theyre blaming you, yet they pray for your return.

No, I cant stay.I didnt want anyone to know Im here so I came this early.

Where will you go?

Anywhere.Im alone.He stood up. I must go.

Roy was awakened by our conversation.He came into the kitchen.

Roy this is Dayleg, I said.

They shook hands.Dayleg turned o me.I must go, he said.

I followed him to the door.I said, Anytime you want to come back

Thanks, he said.

The sacrifice tonight

No, I cant.

His figure was swallowed by the early morning before I could say anything more.

The sacrifice began three hours after noon.Five men, their necks and arms coppery with

sweat, dragged a cow down to the village square where a big wooden table had been

set.The elders had formed a circle around this table and were already praying.The sun cast

their shadows in jagged patterns across the wooden planks as their voices interlaced in

supplication, as the cow, being tied now temporarily to an iron stake, gazed at the solemn

gathering; the fire burned fiercer under the big iron vats and small tin pots while the brass

gongs were brought out of the chieftains hut and hung on their wooden pegs near the

avocado trees where the young men would take turns beating them.Small boys arrived from

the forest bearing in the crook of their arms firewood and dead leaves that would lessen the

nights chill.

At sunset, the praying stopped.In single file the elders walked slowly toward the cow; they

surrounded the animal and, as if somebody had given a signal, knelt before it.They uttered

some inaudible incantation, their heads bowed, giving the impression that they were

addressing themselves.Once in a while the leaders voice rose above the murmurs of the

others.He would stand up, stamp his foot several times, then kneel again.Finally, they all

stood up their ancient faces yellowish in the flickering firelight silent.The leader raised

his right hand.Immediately a barrel-chested muscular man appeared from outside the

circle.He looked at the leaders eyes and read the message there, for he nodded, the leader

having said nothing.Quickly he stepped aside to allow the elders to pass and return to the

table to resume their prayer.Not long afterward the deafening cry of the crying cow

drowned out the elders voices:it flew above the clatter of pots and pans and the whispering

of the women as they prepared the boiling water and tended the fire; then, all of a sudden,

it was gone.A group of men had converged around the cow; from where we stood we could

see knives flashing in the moonlight.

What are they doing?Roy said.

Cleaning the animal.The entrails will be buried near the sacred grove before the cow is

roasted, I said.

They had dug a roasting pit, about six feet wide, ten feet long, and three feet deep, where

live coal was dumped.Two big forking branches of mountain pine were hammered into the

ground to serve as a cradle for the pole that impaled the animal to turn on.

A pity to waste such meat, Roy said.

It wontbe wasted.They will eat it after a portion has been properly offered to the gods.This

is actually a feast, you know, with lots of wine going around.

As the animal was being raised above the pit to roast, the dancing began.The clang of brass

gongs preceded a group of men and women whose feet bent the grass to the strange

uneven rhythm, their arms outstretched fluttering in alar animation, who formed two long

lines.The strange uneven rhythm had a logic to it for the dancers never missed a step,

never hesitated; the strange uneven rhythm had a logic to it for the dancers moved as if

synchronized in sure and easy steps even as a couple swung in between the lines to join

them.A native told me once that dancing was not really taught to the children the children

learned by watching and carrying the rhythm in their heads, memorizing it even in sleep,

making it a part of their bones.So when they danced they danced as though mesmerized, as

these dancers now were, eyes glazy in the moving firelight.Dance, brothers and sisters,

they seemed to say; the gods watch, and the gods must be appeased.

We left the dancers and returned to the roasting pit.The cow was now exuding a delicious

smell as its fat trickled down the burning coal, producing tiny hisses as it touched the

embers; the skin was golden brown and, as the animal was turned by two equally smoke-

burnt men while others watched and waited, full of brightness.

As the night deepened, more fires were built; but the elders continued praying, the tone of

their thaumaturgic throats never wavering nor slowing, while Roy and I sat on a boulder

behind them to rest awhile.There was little for us to do.We were strangers:our lives were

not entangled in these ritualistic complexities.Our world was on the other side of the

Mountains.Yet I felt I was part of all these for I had stepped into the sacred grove and had

stalked its sacred occupant.The reality of my guilt had laid a heavy hand on my heart, and

even now as I heard the primitive music I could not help imagining that it was exorcising

the demon in me.

MY thoughts were interrupted by the noise of a commotion emanating from a section of the

square.The elders abruptly stopped praying and turned their heads to the direction of the

dancers.The natives shouted as they pressed forward nearer the avocado trees.I looked at

Toy.Then [sic] we ran.The sounds of gongs grew louder and louder than the pounding of my

heart against its ribcage as we approached the thick circle of people straining their necks to

see the object of the perturbation.We elbowed our way through to the center of the

crowd.For a while I rubbed my smoke-filled eyes for I thought I was dreaming, but there,

caught in the glare of the bright firelight, was a lone man dancing, the ends of his G-string

flapping as he moved unerringly to the strange uneven rhythm of the goings while shifting

shadows drew myriad patterns on his golden chest, his arms elegant in their winging, his

feet affirming his thanage of the earth, his long hair and loose beard wavelike in the wind

while the people whispered, Hes back, Dayleg, Dayleg, and the elders caressed the sky

with their eyes and gazed at him reduced to a thin pathetic remnant of a man by the mills

of the gods, him the hunter, expressing the threads of mountain history that held his

muscles and bones in the frenzy of autochthonous grace now unleashed purely, and that

contorted his face into a mask of grave pain until tears came to wash his beard and glimmer

in the light, and, as his feet stamped the ground in syllables of penance, they commenced

carving that portion o fate cow for the gods he had returned but the gods had a long

memory they carved the meat while in the circle, wrapped in a spell, he kept on dancing,

figure of a man fallen and rising again, with his feet and arms and soul declaring his

inviolable kinship with all that made him what he was and what he would be, there in the

circle, oh how he danced.

The next morning I packed my bags and told Roy I was going back to the City with

him.There were many things I had to do.We could still catch the six oclock bus.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The RitualDocumento25 pagineThe RitualKirstine DelegenciaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Ritual by Cirilo F. BautistaDocumento4 pagineThe Ritual by Cirilo F. BautistaAlphie Bersabal50% (2)

- Sugar Dark - Umerareta Yami To ShoujoDocumento271 pagineSugar Dark - Umerareta Yami To Shoujoforf95 zoneNessuna valutazione finora

- The Songwriter And The First Christmas And Other Short StoriesDa EverandThe Songwriter And The First Christmas And Other Short StoriesNessuna valutazione finora

- The Black Rose Chronicles: Forever and the Night, For All Eternity, Time Without End, and Tonight and AlwaysDa EverandThe Black Rose Chronicles: Forever and the Night, For All Eternity, Time Without End, and Tonight and AlwaysValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- The Rusalka Ritual & Other Stories: Dragonscale Dimensions, #1Da EverandThe Rusalka Ritual & Other Stories: Dragonscale Dimensions, #1Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Thief Who Spat In Luck's Good Eye: The Amra Thetys Series, #2Da EverandThe Thief Who Spat In Luck's Good Eye: The Amra Thetys Series, #2Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (8)

- Blue Mercy: A Heartbreaking, Page-Turning Irish Family DramaDa EverandBlue Mercy: A Heartbreaking, Page-Turning Irish Family DramaValutazione: 2 su 5 stelle2/5 (5)

- A Frost Of Fear And Fortitude: Tales Of Levanthria, #1Da EverandA Frost Of Fear And Fortitude: Tales Of Levanthria, #1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Wrath and Wraiths: Chronicles of the Dawnblade book 4Da EverandWrath and Wraiths: Chronicles of the Dawnblade book 4Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lord of the Crookside (Book Five of the Nine Suns)Da EverandLord of the Crookside (Book Five of the Nine Suns)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Gatsby and the Lost American DreamDocumento6 pagineGatsby and the Lost American DreamMasha PlayingNessuna valutazione finora

- WTF - Lodges, The SplinteredDocumento146 pagineWTF - Lodges, The SplinteredFarago KatalinNessuna valutazione finora

- GHB FactsheetDocumento2 pagineGHB FactsheetABC Action NewsNessuna valutazione finora

- VFTO DocumentationDocumento119 pagineVFTO DocumentationSheri Abhishek ReddyNessuna valutazione finora

- Theoritical and Applied LinguisticDocumento6 pagineTheoritical and Applied LinguisticOdonkz Forrealracingtiga100% (2)

- Wag Acquisition v. Vubeology Et. Al.Documento29 pagineWag Acquisition v. Vubeology Et. Al.Patent LitigationNessuna valutazione finora

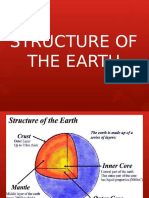

- Earth's StructureDocumento10 pagineEarth's StructureMaitum Gemark BalazonNessuna valutazione finora

- Understanding the Difference Between Positive and Normative EconomicsDocumento21 pagineUnderstanding the Difference Between Positive and Normative EconomicsKevin Fernandez MendioroNessuna valutazione finora

- 09-04-2023 - Plumbing BOQ Without RatesDocumento20 pagine09-04-2023 - Plumbing BOQ Without RatesK. S. Design GroupNessuna valutazione finora

- ICT Backup Procedure PolicyDocumento8 pagineICT Backup Procedure PolicySultan BatoorNessuna valutazione finora

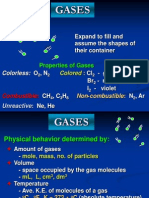

- Properties and Behavior of GasesDocumento34 pagineProperties and Behavior of GasesPaul Jeremiah Serrano NarvaezNessuna valutazione finora

- Business Analytics ModuleDocumento22 pagineBusiness Analytics ModuleMarjon DimafilisNessuna valutazione finora

- Sample Problems Part FormDocumento4 pagineSample Problems Part FormkenivanabejuelaNessuna valutazione finora

- Climate Change ReactionDocumento2 pagineClimate Change ReactionAngelika CotejoNessuna valutazione finora

- Apostolic Faith: Beginn NG of World REV VALDocumento4 pagineApostolic Faith: Beginn NG of World REV VALMichael HerringNessuna valutazione finora

- Business Research Chapter 1Documento27 pagineBusiness Research Chapter 1Toto H. Ali100% (2)

- Gram Negative Rods NonStool Pathogens FlowchartDocumento1 paginaGram Negative Rods NonStool Pathogens FlowchartKeithNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To Computing Week 2Documento23 pagineIntroduction To Computing Week 2Jerick FernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- Land, Soil, Water, Natural Vegetation& Wildlife ResourcesDocumento26 pagineLand, Soil, Water, Natural Vegetation& Wildlife ResourcesKritika VermaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lala Hardayal - BiographyDocumento6 pagineLala Hardayal - Biographyamarsingh1001Nessuna valutazione finora

- Baroque MusicDocumento15 pagineBaroque Musicthot777100% (2)

- The Syntactic Alignments Across Three-Ar PDFDocumento441 pagineThe Syntactic Alignments Across Three-Ar PDFabiskarNessuna valutazione finora

- How Ventilators Deliver BreathsDocumento51 pagineHow Ventilators Deliver BreathsArnaldo SantizoNessuna valutazione finora

- Contract Law 17Documento1 paginaContract Law 17lorraineNessuna valutazione finora

- On The Optimum Inter-Stage Parameters For Co Transcritical Systems Dr. Dan ManoleDocumento8 pagineOn The Optimum Inter-Stage Parameters For Co Transcritical Systems Dr. Dan Manolemohammed gwailNessuna valutazione finora

- Image/Data Encryption-Decryption Using Neural Network: Shweta R. Bhamare, Dr. S.D.SawarkarDocumento7 pagineImage/Data Encryption-Decryption Using Neural Network: Shweta R. Bhamare, Dr. S.D.SawarkarPavan MasaniNessuna valutazione finora

- 2.3 Temperature Conversions: Chapter 2 Energy and MatterDocumento18 pagine2.3 Temperature Conversions: Chapter 2 Energy and MatterBeverly PamanNessuna valutazione finora

- Yealink Device Management Platform: Key FeaturesDocumento3 pagineYealink Device Management Platform: Key FeaturesEliezer MartinsNessuna valutazione finora

- Vaiana Et Al (2021)Documento11 pagineVaiana Et Al (2021)Raffaele CapuanoNessuna valutazione finora

- TK17 V10 ReadmeDocumento72 pagineTK17 V10 ReadmePaula PérezNessuna valutazione finora

- Dslam Commissioning Steps Punjab For 960 PortDocumento8 pagineDslam Commissioning Steps Punjab For 960 Portanl_bhn100% (1)

- Corporate Social Responsibility International PerspectivesDocumento14 pagineCorporate Social Responsibility International PerspectivesR16094101李宜樺Nessuna valutazione finora