Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Final Presentation Usoga Crude Oil Ban April 10 2014 Bob Slaughter

Caricato da

api-257103487Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Final Presentation Usoga Crude Oil Ban April 10 2014 Bob Slaughter

Caricato da

api-257103487Copyright:

Formati disponibili

555 12

th

Street, NW Suite 630B Washington, DC 20004 T: 202-393-3777 www.thomasadvisors.com

The Crude Oil Export Ban

Presented by

Bob Slaughter

2

The Crude Oil Export Ban

Additional Support in Congress and the Executive Branch is

Needed to Improve the Chances for Crude Oil Exports

3

How Did We Get Here? A Short History

4

What is Involved in Securing a Waiver from the Crude Oil

Export Ban?

6

The Jones Act

8

What Happens to Gasoline Prices if the Crude Oil Ban is

Lifted?

8

Possible Ways Forward

9

3

Additional Support in Congress and the Executive Branch is Needed to

Improve the Chances for Crude Oil Exports

This month the chairman of the U.S. House Homeland Security

Committee, Michael McCaul (R-Texas), introduced legislation to lift the existing

U.S. ban on exports of crude oil. Senator Ted Cruz (R-Texas) has also

introduced a bill -- in the Senate -- that would eliminate the ban, among other

provisions. It is highly appropriate that Texans in Congress would take the bit

between their teeth and craft legislative provisions that address the need to

revisit the controversial crude oil export ban.

For one thing, Texas is a petro state in the process of tripling its own oil

production over the current four years (2012-2016) to reach 3 million barrels per

day. Texas oil production will soon be above that of most OPEC member

countries. Tight oil formations like Eagle Ford and Permian Basin are at the

forefront of unconventional fuel production, and, along with production from other

areas in Texas and New Mexico already added roughly 1 million barrels per day

to total U.S. liquids output between 2008 and 2012.

Also, the debate over crude oil exports can use some Texas initiative to

gain and maintain the attention of policymakers in Congress and at the White

House on the critical issue of enabling some level of crude oil exports.

The participation of the House Homeland Security Chairman in introducing

and pushing this legislation demonstrates the continuing importance of energy

supply issues to U.S national security. The need for this was most recently

evident in Russias absorption of Crimea and its aftermath. There is still little

evidence that Russia is seriously concerned about effective reprisal.

Still, given the connection between U.S. foreign policy and oil and gas

production, it is good to know that those responsible for Americas energy

defense are at the forefront of the congressional debate over energy issues and

in the loop. And it is especially reassuring to see that House and Senate GOP

leadership will be actively engaged in efforts to reconsider the wisdom of

continuing the crude oil ban, at least in its current form.

It is also a positive step to see other key policymakers speaking up in

support of the many things that have been done by ranking Republican Senator

Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) to keep the export ban issue before policymakers and

the general public. The new Chair of the Senate Energy Committee, Mary

Landrieu, also seems ready to demonstrate bipartisan support for addressing the

export ban issue. In the interest of completeness, it should be pointed out that

Senators Murkowski and Landrieu are interested in demonstrating that the

Commerce Department retains authority to repeal the ban or restructure it

through a regulatory pathway. Regulatory and/or piecemeal revisitation of the

export ban issue could in the end be the only path forward for 2014, given the

fact that this is and will remain a highly politicized election year.

4

How Did We Get Here? A Short History

The ban on crude oil exports was born in reaction to the events of the

early 1970s. Despite the general impression that the United States in the Sixties

was the absolute model for a nation in disarray, the 1970s were at least as

disruptive as the 1960s, perhaps many more times so.

That decade began with the imposition of wage and price controls across

the nation for 90 days, as a means of implementing the end of the gold standard

and U.S. abandonment of the Bretton Woods agreement. Crude oil, oil products

such as gasoline and diesel, and natural gas prices became subject to federal

wage and price controls declared effective on August 15, 1971.

Almost simultaneously, the most threatening international situations

developed. The war in Vietnam was coming to an ignominious end and still

occupied much of the attention of President Nixon and his advisors. Trouble was

also brewing in the Middle East, which had been an extremely volatile region

since the establishment of the Israeli state and the Suez Canal crisis. The U.S.

dodged a bullet in the 1967 six day war, but it resulted in a whole new set of

grievances that were front and center at the outbreak of the Yom Kippur War on

December 6, 1973. Egypt and Syria, in league with other Arab producers, set

out to raise world oil prices.

American oil production reached its peak in 1970, beginning a slow but

persistent decline until most recently. This situation was compounded by the cut

back or elimination of oil imports headed for the United States. The reduction in

available energy supplies resulted in sharp price increases and shortages of

crude and product. The situation manifested itself through long lines at gasoline

stations if and when they were open and product was available. As a rule, there

were no gasoline sales on Saturday nights or on Sunday. Many policymakers

were advocating adoption of permanent price controls and gasoline rationing.

On October 16, 1973 OPEC raised its posted oil price to $5.11 per barrel,

a 70% price increase. The next day OPEC cut production again by 5%. Western

policymakers, and particularly those from the United States, realized two things:

(1) an accommodation of some kind must take place with OPEC and others in

the Middle East to restore some sense of continuity and stability; and (2) the

West must face the reality that it could not continue to increase energy

consumption by 5% annually. A former U.S. Ambassador to Saudi Arabia

accepted a secret mission to conduct an audit of the U.S. energy position after

the embargo. Ambassador Akins determined that the United States had no

spare capacity and that U.S. oil production would continue to decrease. The

outlook was bleak; but there was nothing left to do but face the facts and move

on.

In the meantime, the Ford Administration continued Nixon economic and

energy policies. The most significant action taken was passage of the

5

Emergency Petroleum Allocation Act, which imposed price, production, allocation

and market controls implemented by the Executive Branch on November 27,

1973.

Meanwhile, the Arab oil embargo doubled the real price of crude at the

refinery level, causing the street price of oil and oil products to quadruple. The

White House sent out Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to sell Project

Independence as an antidote; and the Democratic majorities in the House and

Senate decided instead to legislate. The vehicle was an omnibus energy bill

entitled the Energy Conservation and Policy Act, EPCA, 1975. The statute was

crafted in an atmosphere of fear of resource scarcity, especially of oil and gas.

Among many other things, the statute extended the authority under the

Emergency Petroleum Allocation Act to regulate price and allocation of oil and oil

products. (Natural gas was already regulated under the authority of the Natural

Gas Act.) In the timeframe of EPCAs consideration by the House and Senate

there were tremendous debates and all-out arguments regarding oil and gas

price controls. Liberal, pro-regulation lawmakers won both fights, but just by the

skin of their teeth. And time was not on their side. In another time (1981) and

place (the White House) both oil and natural gas price controls would ultimately

be abandoned.

The sponsors of the EPCA bill also incorporated CAF (corporate average

fuel economy) standards for automobiles and authorized establishment of the

U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR). They also added a provision to the bill

that for all intents and purposes legislated a ban on crude oil exports,

implementation of which was delegated to the Department of Commerce.

Senator Henry Jackson (D-WA) was a major player in developing and advocating

the crude oil export ban.

The statute had little or no impact on domestic production or prices because U.S.

consumption far surpassed production.

With the advent of the modern energy revolution, however, and the strong

increase in U.S. oil and gas production fuel from shale gas and tight oil, the ban

suddenly became very relevant. Industry and policymakers sought to bring the

subject of crude exports into tighter focus. Hence, the question

6

What is Involved in Securing a Waiver from the Crude Oil Export Ban?

The following is a brief summary of the regulatory regime governing crude

oil exports. The law establishes a general policy of crude oil export prohibition;

exports are possible only under certain narrow exceptions. Bear in mind the fact

that market analysts, companies, and even the current Secretary of Energy have

publicly commented on the need to reconsider current export regulations, which

are both arbitrary and confusing. Lets quickly address the policy governing each

hydrocarbon:

Natural gas: can be exported. Permits for LNG terminals are granted on

a project-by-project basis, and the process differs, based on destination.

LNG products also must go through a safety and environmental review

process. The DOE will grant export authorizations unless the export is

found to be not consistent with the public interest. And the requests are

swiftly and automatically approved if submitted for or by countries with

which the U.S. has a free trade agreement.

Natural gas liquids - can be exported to any country, regardless of the

needs of the U.S. market. The five natural gas liquids are butane,

isobutane, natural gasoline, propane and ethane.

Crude oil Crude oil can be exported to Canada (so long as it stays in

Canada or if the product is exported back to the United States).

Petroleum products There are no restrictions on gasoline, diesel and

other petroleum products; they can be exported to any nonsanctioned

country, regardless of the needs of the U.S. market.

Condensate Like crude oil, condensate comes straight off a wellhead

and is lightly processed, while plant condensate results from the

processing of natural gas in a natural gas processing plant. Chemically,

lease condensate and plant condensate (natural gasoline) are essentially

the same thing. This material can end up either as natural gasoline or

plant condensate, depending on whether the weather is hot or cold at the

time of production. Also, field-derived lease condensate can only be

exported to Canada, while natural gasoline is treated as an NGL and can

be exported to any nonsanctioned country, regardless of the needs of the

U.S. market.

7

After reviewing these classifications, it is difficult to reach any other

conclusion but that the different categories are arbitrary and, frankly,

inconsistent. And there are additional details used for classification of oils that we

havent discussed yet.

There are also different categorization of types and locations of oil:

Alaskan North Slope Crude that travels through the TAPS pipeline system,

California heavy crude, crude to Canada, Cook inlet crude, and swaps. As a

matter of fact, the two most obvious categories for waivers or exceptions to the

ban would involve crude of Canadian origin, and crude from countries with which

we have a trade agreement.

The Department of Commerce has generally approved U.S. exports to

Canada for domestic consumption but, as is the case with tight crude (light,

sweet crude), at some point there could quite possibly be a glut on the market,

resulting in having to shut in some or all of this production. There are signs that

the U.S. may be approaching that point. Throughout this discussion one can not

escape the conclusion that we in the U.S. have shifted from a position of energy

shortage to one of surplus, and that policy has yet to catch up.

Due to the Modern Energy Revolution that has already greatly increased

tight oil and natural gas production, hydrocarbon production is still accelerating.

U.S. oil production is at the highest level in 25 years. Analysts point out that the

U.S. has added the equivalent of an Iraq to world markets in the past five years.

The U.S. finds itself in a position of abundance of natural gas liquids, natural gas

and crude oil of the lighter grades. It is difficult to fathom how the markets can

work efficiently if there is not an escape valve so that exports of these plentiful

products can proceed.

According to the EIA and others, U.S. oil demand is flattening out and

American production is rapidly increasing. And most of the growth in oil

consumption is occurring in China, Japan and the third world. Doesnt that

indicate that some level of exports should be available to help balance supply

and demand??

This situation calls clearly for a change in current law. The ban distorts the

energy market and creates inefficiencies. Keeping the ban could result in

artificially low prices which in turn discourage investment in new wells both at

present and in the future. Opponents of a ban also stress that the United States

is a longtime proponent of free trade and seems hypocritical when it condemns

other trade restrictions while hanging on to one that protects its own crude oil

exports.

The Secretary of Energy recently mentioned that some of the regulations

in the energy area have not been reviewed for some time. But the Commerce

Department, which is responsible for regulations involving crude oil exports, has

not yet entered the fray. It is clear that there is already some interest in this issue

in the House and Senate as discussed in the opening section of this study. But

8

Congress is currently tied up in knots and may not be able to resolve this

problem in the immediate future. Legislative action to eliminate the ban would

seem to be very difficult to come by before the midterm elections.

The Jones Act

One issue that should also be taken into consideration is the impact of the

Jones Act, which requires that shipping between two American ports requires an

American boat with an American crew. The earliest statute to this effect was

approved by Congress in 1789, so the idea has been around for a while. It is

theoretically possible to obtain Jones Act waivers, but very difficult. The impact

of the Act is to increase shipping charges where the Act applies, and to create

bottlenecks that benefit some market participants and penalize others, all in the

name of protecting the American maritime fleet.

In practice, it would be difficult if not impossible to address Jones Act

issues at the same time that the issues of crude oil exports are addressed.

However, the issue can be expected to appear as an example of a market

distortion that might be used in an attempt to shelter or sustain other market

distortions that arise when the crude export issue is discussed and debated.

Senators Menendez (D-NJ) and Markey (D-MA) have come out strongly

against making changes in the statutes that authorize the ban. They argue that

the rationale for the ban remains valid. Analysts and industry supporters of

changing the policy on crude exports are increasingly concerned that outright

repeal this year might be too heavy a lift. But, at the same time, economic theory

and historical experience have demonstrated that bans cause bottlenecks and

wasteful spending and constitute a poor policy choice.

In the meantime, crude oil production in the U.S. continues to ratchet up.

There are strong ongoing efforts to explain the need for crude exports, supported

by most corporate trade associations such as API and the U.S. Chamber of

Commerce, among many others. Hopefully this broad outreach effort will help the

oil and gas industry and its allies achieve their goals regarding the crude oil

export ban. As the debate unfolds, the available paths become more and more

evident.

What Happens to Gasoline Prices if the Crude Oil Ban is Lifted?

One of the most contentious issues in the debate about whether the crude

oil export ban should be lifted is how U.S. gasoline prices will increase, decrease

or remain unchanged. Resources for the Future addressed this issue in a recent

policy paper: Crude Behavior, Brown, Mason, Krupnich and Mares, RFF, 2014.

RFF: In this issue brief we offer economic logic and estimates from our (RFFs)

modeling and data analysis suggesting that the price of gasoline will likely fall by

around three to seven cents a gallon. As for the danger of higher prices for

9

crude and product in the Midwest if the ban is lifted: RFF: lower crude oil

prices in the Midwest do not seem to have resulted in lower prices (for

consumers) in the Midwest.

And as for the growing mismatch between burgeoning light, sweet tight crude

production and appropriate refining capacity RFF found that lifting the ban on

U.S. crude oil exports would allow for a more efficient distribution of crude oil

among refineries in the Western Hemisphere and elsewhere in the world.

(op.cit.)

Possible Ways Forward:

Legislative Changes: it is possible, but rather unlikely, that Congress will

choose to repeal the EPCA language that establishes the ban. Congress will be

in session only rarely this year, given the advent of the Midterm elections.

Repeal of the ban outright is a controversial matter, and it is not clear that

industry has yet convinced policymakers that Congress should put this item on its

limited agenda for this year. Outright repeal would seem more likely in the next

Congress, especially if one party controls both chambers.

Administrative Changes: The President or Department of Commerce could

establish new and different criteria for approving export licenses. EPCA and

other related statutes give the administration some discretion in this area. For

example, the OCS Act sets up criteria for a waiver subject to Congress right to

disagree with the Presidents decision via a joint resolution. Many different

guidelines or criteria could be established. This waiver could be accomplished

through the Presidents own authority or by direction of Congress. Much

evidence indicates that the President has broad discretion in this area, and his

authority could be strengthened by working with Congress.

But one thing is clear: lawmakers need to rationalize policy on this issue

and to make best use of the many benefits that result from the new energy

revolution. It is very important that the executive and legislative branches work

together, if at all possible, to make changes that promote vigorous competition

and maximum reinvestment in the energy sector.

10

Thomas Advisors, Inc.

Thomas Advisors, Inc. specializes in advising corporations, both domestic and

international, on how to work through the governmental maize to do business and also

represents them in the political process. Currently, Thomas Advisors, Inc. has expertise

in the fields of energy (coal, pipelines, power generation, wind, solar, refining and oil &

gas), drinking and wastewater, environmental services, land management, homeland

security and transportation. In addition to experience with the Legislative Branch of

government, Thomas Advisor professionals work with the Executive Branch including

the EPA, Department of Defense, Department of the Interior, and the Department of

Energy.

Bob Slaughter

Bob Slaughter is a recognized professional who brings more than 40 years of

Washington experience to Thomas Advisors. Prior to joining the firm, Mr. Slaughter

worked for the National Petroleum Refiners Association where he was the President

from 2002 until 2007 when he left Washington to pursue other interests. NPRAs

membership largely consists of the nations oil refiners and petrochemical

manufacturers. While at NPRA, he had extensive experience testifying before

Congressional committees on a host of sensitive and crucial subjects, including gasoline

production and supply, the importance of the refining and chemical industries to the

nation, facility security, and the most significant environmental initiatives. He also

represented the industry in interviews and informal discussions with all national news

media including the Wall Street Journal, New York Times, Washington Post, Los

Angeles Times, National Public Radio, the major television networks, plus Fox News,

Bloomberg News and CNBC.

Prior to NPRA, Mr. Slaughter was employed by Amoco Corporation (later to become BP)

being hired in 1985 to serve as their senior representative in Washington. During this

period he lobbied the Administration and the House and Senate on all major domestic

and international initiatives affecting the petroleum industry and many in the chemical

industry. He took a short leave of absence to serve as the Administrative Assistant to

Senator Robert Krueger (D) while the senator served a brief tenure as the appointed

Senator from Texas.

Before joining Amoco, Mr. Slaughter was in charge of Pacific Resources Incorporateds

Washington office, and served as liaison to the corporations General Counsel involved

with refining, alternative energy and synthetic gas-related issues as well as non-energy

issues important to the state of Hawaii. He also worked for the Natural Gas Supply

Association working on natural gas issues.

From 1979 until 1981, Mr. Slaughter was the energy advisor to Ambassador at large and

Coordinator of U.S.-Mexican Relations, Robert Krueger, at the State Department in

Washington. In this position he worked with the Mexican desk and other State

Department personnel, up to and including the Secretarys office. His focus was largely

on energy-related issues that directly affected U.S.-Mexican relations. Prior to this

international experience, Bob served then Congressman Bob Krueger (D- Texas) as his

energy legislative assistant, helping to manage consideration of a bill to deregulate

natural gas prices in addition to managing several energy and other legislative initiatives

on the House floor.

11

Bob began his career as an entry-level staffer in the offices of his two home state

Senators, William Saxbe (R-OH) and Howard Metzenbaum (D-OH). Mr. Slaughter

earned a JD (cum Laude) from Georgetown Law School and a B.A. from Yale University.

Thomas J. Medaglia, III

In 1986, Mr. Medaglia was employed by Amoco Corporation as their company lobbyist in

Michigan, Ohio, Indiana and Kentucky. Later, he was promoted to Director of State

Relations with responsibility for overseeing the companys state government affairs

program in the U.S. In 1994, Mr. Medaglia was promoted to Washington, D.C. as

Director of Federal Relations where he was responsible for upstream and pipeline

issues. International Washington assignments included the Middle East, India and

Eastern Europe. After the merger with British Petroleum where he was part of the

Amoco merger team, he continued to have the same responsibilities for upstream and

pipeline issues with the newly created company named BP with emphasis on areas such

as the Gulf of Mexico and Alaska activities.

Mr. Medaglia retired from BP to become president of RWE North America Corp, the U.S.

holding company for RWE AG, a large German energy company. During this time he

was responsible for external affairs in addition to coordinating the U.S. CEO messaging

of their U.S. operations with that of RWE AG, the worldwide parent company. U.S.

subsidiaries included American Water, CONSOL Energy, NUKEM and Turner

Construction. Additionally, Mr. Medaglia was successful in growing the domestic

reputation of RWE AG and achieved support from the U.S. Administration for RWE AGs

Nabucco pipeline. This proposed pipeline would transport gas from the Caspian Sea via

Turkey to Europe. Mr. Medaglia was part of the team that successfully petitioned and

secured the various state approvals for RWE AGs Thames Water acquisition of

American Water, the largest private water and wastewater company in the United States

at the time.

Prior to Amoco, Mr. Medaglia practiced law in Ohio and Michigan specializing in

corporate, real estate, workers and unemployment compensation law in addition to

representing professional athletes in contract negotiations. During this time, he also

designed, developed and owned a restaurant and comedy club chain in the Midwest.

Mr. Medaglia is currently an Adjunct Professor of Law and Public Policy at Northwood

University where he teaches an interim Public Policy and Constitutional Law course in

Washington, D.C. He is also an advisor to the U.S. Oil and Gas Association and is a

yearly guest speaker at The American Association of Professional Landmens (AAPL)

Washington fly-in.

Mr. Medaglia holds a B.A. in Education from The Ohio State University and a Juris

Doctor degree from Thomas M. Cooley Law School, Michigan. He is licensed to practice

law in Ohio and Michigan and is a member of the United States Supreme Court. Tom is

a Board Member of the Ripon Society and a founding Board Member of the German

American Business Council. He is also a member of several business associations.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- 1nc Compiled MasterfileDocumento246 pagine1nc Compiled MasterfileYichen SunNessuna valutazione finora

- EXCLUSIVE: 16 Republican States Demand Biden Reinstate Keystone XL PipelineDocumento4 pagineEXCLUSIVE: 16 Republican States Demand Biden Reinstate Keystone XL PipelineGabe Kaminsky100% (1)

- Med Error PaperDocumento4 pagineMed Error Paperapi-314062228100% (1)

- Final Report On HR 702Documento19 pagineFinal Report On HR 702johnNessuna valutazione finora

- Senate Hearing, 114TH Congress - Lifting The Crude Oil Export BanDocumento59 pagineSenate Hearing, 114TH Congress - Lifting The Crude Oil Export BanScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Senate Hearing, 110TH Congress - Oil Shale ResourcesDocumento105 pagineSenate Hearing, 110TH Congress - Oil Shale ResourcesScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- LNG Coal ReportDocumento16 pagineLNG Coal ReportNWDailyMarkerNessuna valutazione finora

- House Hearing, 114TH Congress - The Crude Oil Export Ban: Helpful or Hurtful?Documento73 pagineHouse Hearing, 114TH Congress - The Crude Oil Export Ban: Helpful or Hurtful?Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Offshore Drilling Aff & Neg - CNDI Starter PackDocumento176 pagineOffshore Drilling Aff & Neg - CNDI Starter Packpacifist42Nessuna valutazione finora

- Statement of Adam SieminskiDocumento10 pagineStatement of Adam Sieminskilolo buysNessuna valutazione finora

- Senate Hearing, 110TH Congress - Oil Inventory PoliciesDocumento83 pagineSenate Hearing, 110TH Congress - Oil Inventory PoliciesScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Jonathan Chanis, U.S. Liquefied Natural Gas Exports and America's Foreign Policy InterestsDocumento7 pagineJonathan Chanis, U.S. Liquefied Natural Gas Exports and America's Foreign Policy InterestsRui Henrique SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- FuelingthefuturebillDocumento3 pagineFuelingthefuturebillapi-329461768Nessuna valutazione finora

- Senate Hearing, 112TH Congress - Gas Prices in The Northeast: Potential Impact On The American Consumer Due To Loss of Refining CapacityDocumento57 pagineSenate Hearing, 112TH Congress - Gas Prices in The Northeast: Potential Impact On The American Consumer Due To Loss of Refining CapacityScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Obama Energy Speech Fact CheckDocumento9 pagineObama Energy Speech Fact CheckSenateRPCNessuna valutazione finora

- Time To Lift The Ban On Crude Oil ExportsDocumento7 pagineTime To Lift The Ban On Crude Oil Exportsmdmorgan88Nessuna valutazione finora

- House Hearing, 113TH Congress - The Crude Truth: Evaluating U.S. Energy Trade PolicyDocumento67 pagineHouse Hearing, 113TH Congress - The Crude Truth: Evaluating U.S. Energy Trade PolicyScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Energy Myths and Realities: Bringing Science to the Energy Policy DebateDa EverandEnergy Myths and Realities: Bringing Science to the Energy Policy DebateValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (4)

- Energy Outlook For The WorldDocumento3 pagineEnergy Outlook For The Worldfernando torresNessuna valutazione finora

- GG 1acDocumento16 pagineGG 1acAlonso Pierre PenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Senate Hearing, 111TH Congress - Strategic Petroleum ReserveDocumento65 pagineSenate Hearing, 111TH Congress - Strategic Petroleum ReserveScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- House Hearing, 110TH Congress - Pumping Up Prices: The Strategic Petroleum Reserve and Record Gas PricesDocumento126 pagineHouse Hearing, 110TH Congress - Pumping Up Prices: The Strategic Petroleum Reserve and Record Gas PricesScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Energy Security and Oil Dependence: HearingDocumento61 pagineEnergy Security and Oil Dependence: HearingScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Critical Energy Choices For The Next AdministrationDocumento20 pagineCritical Energy Choices For The Next AdministrationThe American Security ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- The U.S. Shale Oil Boom, The Oil Export Ban, and The Economy: A General Equilibrium AnalysisDocumento61 pagineThe U.S. Shale Oil Boom, The Oil Export Ban, and The Economy: A General Equilibrium Analysisag rNessuna valutazione finora

- Outraged State Attorneys Sue Over Big Oil Price GougingDocumento2 pagineOutraged State Attorneys Sue Over Big Oil Price GougingProtect Florida's BeachesNessuna valutazione finora

- Running On Empty - HollandDocumento2 pagineRunning On Empty - HollandThe American Security ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- Adelman OilShortageReal 1972Documento40 pagineAdelman OilShortageReal 1972Israt Jahan DinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Nat Gas UsDocumento14 pagineNat Gas UsOsmar RGNessuna valutazione finora

- From The Desk of Rep. Dovilla Around The 18 at The Statehouse Upcoming EventsDocumento4 pagineFrom The Desk of Rep. Dovilla Around The 18 at The Statehouse Upcoming EventsRepresentative Mike DovillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Conflict Climate Change PDFDocumento10 pagineConflict Climate Change PDFRogers Tabe OrockNessuna valutazione finora

- Lives Per Gallon: The True Cost of Our Oil AddictionDa EverandLives Per Gallon: The True Cost of Our Oil AddictionValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (7)

- Saudi America: The Truth About Fracking and How It's Changing the WorldDa EverandSaudi America: The Truth About Fracking and How It's Changing the WorldValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (16)

- 4-5 1970s Energy CrisisDocumento2 pagine4-5 1970s Energy Crisisapi-293733920Nessuna valutazione finora

- Assignment 1Documento4 pagineAssignment 1ANJANI GUPTANessuna valutazione finora

- Energy Security: Historical Perspectives and Modern ChallengesDocumento45 pagineEnergy Security: Historical Perspectives and Modern ChallengesScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Voters Blame President For Gas PricesDocumento6 pagineVoters Blame President For Gas PricesDay YangNessuna valutazione finora

- 516-1855-1-PB THE PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE OF ENERGY REGULATION Richard J. Pierce, JRDocumento17 pagine516-1855-1-PB THE PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE OF ENERGY REGULATION Richard J. Pierce, JRSFLDNessuna valutazione finora

- The Bush/Cheney Energy Strategy: Implications For U.S. Foreign and Military PolicyDocumento21 pagineThe Bush/Cheney Energy Strategy: Implications For U.S. Foreign and Military PolicyjohnrmonettNessuna valutazione finora

- The Fight Over Using Natural Gas for Transportation: AntagonistsDa EverandThe Fight Over Using Natural Gas for Transportation: AntagonistsValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- 2007 The Oil in The Middle EastDocumento6 pagine2007 The Oil in The Middle EastJames BradleyNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Paper Oil PricesDocumento5 pagineResearch Paper Oil Pricesfvfr9cg8100% (1)

- House Hearing, 110TH Congress - Immediate Relief From High Oil Prices: Deploying The Strategic Petroleum ReservesDocumento56 pagineHouse Hearing, 110TH Congress - Immediate Relief From High Oil Prices: Deploying The Strategic Petroleum ReservesScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- End of Fossil FuelsDocumento15 pagineEnd of Fossil FuelsCamilo Andrés GuerreroNessuna valutazione finora

- Index File FYI: Download The Original AttachmentDocumento57 pagineIndex File FYI: Download The Original AttachmentAffNeg.Com100% (1)

- Natural Gas/ Power News: Crestwood Midstream Plans Marcellus Pipeline in West VirginiaDocumento7 pagineNatural Gas/ Power News: Crestwood Midstream Plans Marcellus Pipeline in West VirginiachoiceenergyNessuna valutazione finora

- Peak Oil Review 120521Documento8 paginePeak Oil Review 120521scribd6436Nessuna valutazione finora

- Brookings Energy Transcript JD PDFDocumento10 pagineBrookings Energy Transcript JD PDFisaac setabiNessuna valutazione finora

- Energy Data Highlights: Is Fracking Set To Transform The Oil Market?Documento9 pagineEnergy Data Highlights: Is Fracking Set To Transform The Oil Market?choiceenergyNessuna valutazione finora

- Hr1252sap HDocumento2 pagineHr1252sap HlosangelesNessuna valutazione finora

- Senate Hearing, 108TH Congress - The Long-Run Economics of Natural GasDocumento123 pagineSenate Hearing, 108TH Congress - The Long-Run Economics of Natural GasScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Reflections of a Political Economist: Selected Articles on Government Policies and Political ProcessesDa EverandReflections of a Political Economist: Selected Articles on Government Policies and Political ProcessesNessuna valutazione finora

- Power to the People: How the Coming Energy Revolution Will Transform an Industry, Change Our Lives, and Maybe Even Save the PlanetDa EverandPower to the People: How the Coming Energy Revolution Will Transform an Industry, Change Our Lives, and Maybe Even Save the PlanetValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (4)

- Senate Hearing, 113TH Congress - HeliumDocumento73 pagineSenate Hearing, 113TH Congress - HeliumScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- House Hearing, 112TH Congress - Rising Oil Prices and Dependence On Hostile Regimes: The Urgent Case For Canadian OilDocumento102 pagineHouse Hearing, 112TH Congress - Rising Oil Prices and Dependence On Hostile Regimes: The Urgent Case For Canadian OilScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- House Hearing, 113TH Congress - The New Domestic Energy Paradigm: Downstream Challenges For Small Energy BusinessesDocumento67 pagineHouse Hearing, 113TH Congress - The New Domestic Energy Paradigm: Downstream Challenges For Small Energy BusinessesScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Delloite Oil and Gas Reality Check 2015 PDFDocumento32 pagineDelloite Oil and Gas Reality Check 2015 PDFAzik KunouNessuna valutazione finora

- Hearing: The Hidden Cost of OilDocumento53 pagineHearing: The Hidden Cost of OilScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Shale Gas Hype or RealityDocumento46 pagineShale Gas Hype or Realityshyam_anupNessuna valutazione finora

- Vanishing Peak by William O'KeefeDocumento2 pagineVanishing Peak by William O'Keefechaitanyaamin560Nessuna valutazione finora

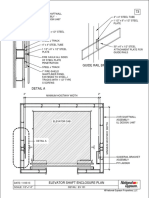

- Guide Rail Bracket AssemblyDocumento1 paginaGuide Rail Bracket AssemblyPrasanth VarrierNessuna valutazione finora

- Luigi Cherubini Requiem in C MinorDocumento8 pagineLuigi Cherubini Requiem in C MinorBen RutjesNessuna valutazione finora

- User Manual - Wellwash ACDocumento99 pagineUser Manual - Wellwash ACAlexandrNessuna valutazione finora

- Analysis of Mozarts k.475Documento2 pagineAnalysis of Mozarts k.475ASPASIA FRAGKOUNessuna valutazione finora

- HOWO SERVICE AND MAINTENANCE SCHEDULE SinotruckDocumento3 pagineHOWO SERVICE AND MAINTENANCE SCHEDULE SinotruckRPaivaNessuna valutazione finora

- 1and5.microscopes, Specializedstem Cells, Homeostasis - Answer KeyDocumento1 pagina1and5.microscopes, Specializedstem Cells, Homeostasis - Answer KeyMCarmen López CastroNessuna valutazione finora

- MBF100 Subject OutlineDocumento2 pagineMBF100 Subject OutlineMARUTI JEWELSNessuna valutazione finora

- Problem Solving Questions: Solutions (Including Comments)Documento25 pagineProblem Solving Questions: Solutions (Including Comments)Narendrn KanaesonNessuna valutazione finora

- Macro Economics A2 Level Notes Book PDFDocumento33 pagineMacro Economics A2 Level Notes Book PDFMustafa Bilal50% (2)

- LLB IV Sem GST Unit I Levy and Collection Tax by DR Nisha SharmaDocumento7 pagineLLB IV Sem GST Unit I Levy and Collection Tax by DR Nisha Sharmad. CNessuna valutazione finora

- Surge Protection Devices GuidesDocumento167 pagineSurge Protection Devices GuidessultanprinceNessuna valutazione finora

- ECDIS Presentation Library 4Documento16 pagineECDIS Presentation Library 4Orlando QuevedoNessuna valutazione finora

- Dur MalappuramDocumento114 pagineDur MalappuramSabareesh RaveendranNessuna valutazione finora

- Revised Study Material - Economics ChandigarhDocumento159 pagineRevised Study Material - Economics ChandigarhvishaljalanNessuna valutazione finora

- Statement 1680409132566Documento11 pagineStatement 1680409132566úméshNessuna valutazione finora

- AOCS Ca 12-55 - 2009 - Phosphorus PDFDocumento2 pagineAOCS Ca 12-55 - 2009 - Phosphorus PDFGeorgianaNessuna valutazione finora

- Rated Operational Current: InstructionsDocumento12 pagineRated Operational Current: InstructionsJhon SanabriaNessuna valutazione finora

- CHAPTER I KyleDocumento13 pagineCHAPTER I KyleCresiel Pontijon100% (1)

- Hormone Replacement Therapy Real Concerns and FalsDocumento13 pagineHormone Replacement Therapy Real Concerns and FalsDxng 1Nessuna valutazione finora

- 20131022-Additive Manufacturing & Allied Technologies, PuneDocumento56 pagine20131022-Additive Manufacturing & Allied Technologies, Puneprakush_prakushNessuna valutazione finora

- Meyer and Zack KM CycleDocumento16 pagineMeyer and Zack KM Cyclemohdasriomar84Nessuna valutazione finora

- Bye Laws For MirzapurDocumento6 pagineBye Laws For MirzapurUtkarsh SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Aruba 8325 Switch SeriesDocumento51 pagineAruba 8325 Switch SeriesgmtrlzNessuna valutazione finora

- Python PyDocumento19 paginePython Pyakhilesh kr bhagatNessuna valutazione finora

- CV's of M.ishtiaqDocumento3 pagineCV's of M.ishtiaqishtiaqNessuna valutazione finora

- VSL Synchron Pianos Changelog en 1.1.1386Documento4 pagineVSL Synchron Pianos Changelog en 1.1.1386RdWingNessuna valutazione finora

- Topics For AssignmentDocumento2 pagineTopics For AssignmentniharaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sample Heat Sheets June 2007Documento63 pagineSample Heat Sheets June 2007Nesuui MontejoNessuna valutazione finora

- Ref Drawing 2. Ref Code: 3. Design DatasDocumento3 pagineRef Drawing 2. Ref Code: 3. Design DatasJoe Nadakkalan100% (3)