Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Everett Steamship Corporation, Petitioner, vs. Court of Appeals and Hernandez Trading Co. INC., Respondents. Decision Martinez, J.

Caricato da

attyyangTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Everett Steamship Corporation, Petitioner, vs. Court of Appeals and Hernandez Trading Co. INC., Respondents. Decision Martinez, J.

Caricato da

attyyangCopyright:

Formati disponibili

1. EVERETT STEAMSHIP CORPORATION, petitioner, vs. COURT OF APPEALS and HERNANDEZ TRADING CO.

INC., respondents.

D E C I S I O N

MARTINEZ, J .:

Petitioner Everett Steamship Corporation, through this petition for review, seeks the reversal of the decision

[1]

of the

Court of Appeals, dated June 14, 1995, in CA-G.R. No. 428093, which affirmed the decision of the Regional Trial Court of

Kalookan City, Branch 126, in Civil Case No. C-15532, finding petitioner liable to private respondent Hernandez Trading

Co., Inc. for the value of the lost cargo.

Private respondent imported three crates of bus spare parts marked as MARCO C/No. 12, MARCO C/No. 13

and MARCO C/No. 14, from its supplier, Maruman Trading Company, Ltd. (Maruman Trading), a foreign corporation

based in Inazawa, Aichi, Japan. The crates were shipped from Nagoya, Japan to Manila on board ADELFAEVERETTE,

a vessel owned by petitioners principal, Everett Orient Lines. The said crates were covered by Bill of Lading No.

NGO53MN.

Upon arrival at the port of Manila, it was discovered that the crate marked MARCO C/No. 14 was missing. This was

confirmed and admitted by petitioner in its letter of January 13, 1992 addressed to private respondent, which thereafter

made a formal claim upon petitioner for the value of the lost cargo amounting to One Million Five Hundred Fifty Two

Thousand Five Hundred (Y1,552,500.00) Yen, the amount shown in an Invoice No. MTM-941, dated November 14,

1991. However, petitioner offered to pay only One Hundred Thousand (Y100,000.00) Yen, the maximum amount

stipulated under Clause 18 of the covering bill of lading which limits the liability of petitioner.

Private respondent rejected the offer and thereafter instituted a suit for collection docketed as Civil Case No. C-

15532, against petitioner before the Regional Trial Court of Caloocan City, Branch 126.

At the pre-trial conference, both parties manifested that they have no testimonial evidence to offer and agreed

instead to file their respective memoranda.

On July 16, 1993, the trial court rendered judgment

[2]

in favor of private respondent, ordering petitioner to pay: (a)

Y1,552,500.00; (b) Y20,000.00 or its peso equivalent representing the actual value of the lost cargo and the material and

packaging cost; (c) 10% of the total amount as an award for and as contingent attorneys fees; and (d) to pay the cost of

the suit. The trial court ruled:

Considering defendants categorical admission of loss and its failure to overcome the presumption of negligence

and fault, the Court conclusively finds defendant liable to the plaintiff. The next point of inquiry the Court wants

to resolve is the extent of the liability of the defendant. As stated earlier, plaintiff contends that defendant should

be held liable for the whole value for the loss of the goods in the amount of Y1,552,500.00 because the terms

appearing at the back of the bill of lading was so written in fine prints and that the same was not signed by

plaintiff or shipper thus, they are not bound by the clause stated in paragraph 18 of the bill of lading. On the

other hand, defendant merely admitted that it lost the shipment but shall be liable only up to the amount of

Y100,000.00.

The Court subscribes to the provisions of Article 1750 of the New Civil Code -

Art. 1750. A contract fixing the sum that may be recovered by the owner or shipper for the loss,

destruction or deterioration of the goods is valid, if it is reasonable and just under the circumstances, and

has been fairly and freely agreed upon.

It is required, however, that the contract must be reasonable and just under the circumstances and has been

fairly and freely agreed upon. The requirements provided in Art. 1750 of the New Civil Code must be complied

with before a common carrier can claim a limitation of its pecuniary liability in case of loss, destruction or

deterioration of the goods it has undertaken to transport.

In the case at bar, the Court is of the view that the requirements of said article have not been met. The fact that

those conditions are printed at the back of the bill of lading in letters so small that they are hard to read would not

warrant the presumption that the plaintiff or its supplier was aware of these conditions such that he had fairly

and freely agreed to these conditions. It can not be said that the plaintiff had actually entered into a contract

with the defendant, embodying the conditions as printed at the back of the bill of lading that was issued by the

defendant to plaintiff.

On appeal, the Court of Appeals deleted the award of attorneys fees but affirmed the trial courts findings with the

additional observation that private respondent can not be bound by the terms and conditions of the bill of lading because it

was not privy to the contract of carriage. It said:

As to the amount of liability, no evidence appears on record to show that the appellee (Hernandez Trading Co.)

consented to the terms of the Bill of Lading. The shipper named in the Bill of Lading is Maruman Trading Co.,

Ltd. whom the appellant (Everett Steamship Corp.) contracted with for the transportation of the lost goods.

Even assuming arguendo that the shipper Maruman Trading Co., Ltd. accepted the terms of the bill of lading

when it delivered the cargo to the appellant, still it does not necessarily follow that appellee Hernandez Trading

Company as consignee is bound thereby considering that the latter was never privy to the shipping contract.

x x x x x x x x x

Never having entered into a contract with the appellant, appellee should therefore not be bound by any of the

terms and conditions in the bill of lading.

Hence, it follows that the appellee may recover the full value of the shipment lost, the basis of which is not the

breach of contract as appellee was never a privy to the any contract with the appellant, but is based on Article

1735 of the New Civil Code, there being no evidence to prove satisfactorily that the appellant has overcome the

presumption of negligence provided for in the law.

Petitioner now comes to us arguing that the Court of Appeals erred (1) in ruling that the consent of the consignee to

the terms and conditions of the bill of lading is necessary to make such stipulations binding upon it; (2) in holding that the

carriers limited package liability as stipulated in the bill of lading does not apply in the instant case; and (3) in allowing

private respondent to fully recover the full alleged value of its lost cargo.

We shall first resolve the validity of the limited liability clause in the bill of lading.

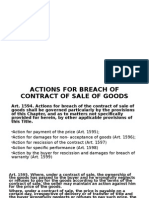

A stipulation in the bill of lading limiting the common carriers liability for loss or destruction of a cargo to a certain

sum, unless the shipper or owner declares a greater value, is sanctioned by law, particularly Articles 1749 and 1750 of the

Civil Code which provide:

ART. 1749. A stipulation that the common carriers liability is limited to the value of the goods appearing in the

bill of lading, unless the shipper or owner declares a greater value, is binding.

ART. 1750. A contract fixing the sum that may be recovered by the owner or shipper for the loss, destruction,

or deterioration of the goods is valid, if it is reasonable and just under the circumstances, and has been freely

and fairly agreed upon.

Such limited-liability clause has also been consistently upheld by this Court in a number of cases.

[3]

Thus, in Sea

Land Service, Inc. vs Intermediate Appellate Court

[4]

, we ruled:

It seems clear that even if said section 4 (5) of the Carriage of Goods by Sea Act did not exist, the validity and binding

effect of the liability limitation clause in the bill of lading here are nevertheless fully sustainable on the basis alone of the

cited Civil Code Provisions. That said stipulation is just and reasonable is arguable from the fact that it echoes Art. 1750

itself in providing a limit to liability only if a greater value is not declared for the shipment in the bill of lading. To hold

otherwise would amount to questioning the justness and fairness of the law itself, and this the private respondent does not

pretend to do. But over and above that consideration, the just and reasonable character of such stipulation is implicit in it

giving the shipper or owner the option of avoiding accrual of liability limitation by the simple and surely far from onerous

expedient of declaring the nature and value of the shipment in the bill of lading..

Pursuant to the afore-quoted provisions of law, it is required that the stipulation limiting the common carriers liability

for loss must be reasonable and just under the circumstances, and has been freely and fairly agreed upon.

The bill of lading subject of the present controversy specifically provides, among others:

18. All claims for which the carrier may be liable shall be adjusted and settled on the basis of the shippers net

invoice cost plus freight and insurance premiums, if paid, and in no event shall the carrier be liable for any loss of

possible profits or any consequential loss.

The carrier shall not be liable for any loss of or any damage to or in any connection with, goods in an amount

exceeding One Hundred Thousand Yen in Japanese Currency (Y100,000.00) or its equivalent in any other

currency per package or customary freight unit (whichever is least) unless the value of the goods higher than this

amount is declared in writing by the shipper before receipt of the goods by the carrier and inserted in the Bill of

Lading and extra freight is paid as required.(Emphasis supplied)

The above stipulations are, to our mind, reasonable and just. In the bill of lading, the carrier made it clear that its

liability would only be up to One Hundred Thousand (Y100,000.00) Yen. However, the shipper, Maruman Trading, had

the option to declare a higher valuation if the value of its cargo was higher than the limited liability of the

carrier. Considering that the shipper did not declare a higher valuation, it had itself to blame for not complying

with the stipulations.

The trial courts ratiocination that private respondent could not have fairly and freely agreed to the limited liability

clause in the bill of lading because the said conditions were printed in small letters does not make the bill of lading invalid.

We ruled in PAL, Inc. vs. Court of Appeals

[5]

that the jurisprudence on the matter reveals the consistent holding of

the court that contracts of adhesion are not invalidper se and that it has on numerous occasions upheld the binding effect

thereof. Also, in Philippine American General Insurance Co., Inc. vs. Sweet Lines , Inc.

[6]

this Court , speaking

through the learned Justice Florenz D. Regalado, held:

x x x Ong Yiu vs. Court of Appeals, et.al., instructs us that contracts of adhesion wherein one party imposes a

ready-made form of contract on the other x x x are contracts not entirely prohibited. The one who adheres to

the contract is in reality free to reject it entirely; if he adheres he gives his consent. In the present case, not

even an allegation of ignorance of a party excuses non-compliance with the contractual stipulations since the

responsibility for ensuring full comprehension of the provisions of a contract of carriage devolves not on the

carrier but on the owner, shipper, or consignee as the case may be. (Emphasis supplied)

It was further explained in Ong Yiu vs Court of Appeals

[7]

that stipulations in contracts of adhesion are valid and

binding.

While it may be true that petitioner had not signed the plane ticket x x, he is nevertheless bound by the

provisions thereof. Such provisions have been held to be a part of the contract of carriage, and valid and

binding upon the passenger regardless of the latters lack of knowledge or assent to the regulation. It is what is

known as a contract of adhesion, in regards which it has been said that contracts of adhesion wherein one party

imposes a ready-made form of contract on the other, as the plane ticket in the case at bar, are contracts not

entirely prohibited. The one who adheres to the contract is in reality free to reject it entirely; if he adheres, he

gives his consent. x x x , a contract limiting liability upon an agreed valuation does not offend against the policy

of the law forbidding one from contracting against his own negligence. (Emphasis supplied)

Greater vigilance, however, is required of the courts when dealing with contracts of adhesion in that the said

contracts must be carefully scrutinized in order to shield the unwary (or weaker party) from deceptive schemes contained

in ready-made covenants,

[8]

such as the bill of lading in question. The stringent requirement which the courts are

enjoined to observe is in recognition of Article 24 of the Civil Code which mandates that (i)n all contractual, property or

other relations, when one of the parties is at a disadvantage on account of his moral dependence, ignorance,

indigence, mental weakness, tender age or other handicap, the courts must be vigilant for his protection.

The shipper, Maruman Trading, we assume, has been extensively engaged in the trading business. It can not be

said to be ignorant of the business transactions it entered into involving the shipment of its goods to its customers. The

shipper could not have known, or should know the stipulations in the bill of lading and there it should have declared a

higher valuation of the goods shipped. Moreover, Maruman Trading has not been heard to complain that it has been

deceived or rushed into agreeing to ship the cargo in petitioners vessel. In fact, it was not even impleaded in this case.

The next issue to be resolved is whether or not private respondent, as consignee, who is not a signatory to the bill of

lading is bound by the stipulations thereof.

Again, in Sea-Land Service, Inc. vs. Intermediate Appellate Court (supra), we held that even if the consignee

was not a signatory to the contract of carriage between the shipper and the carrier, the consignee can still be bound by

the contract. Speaking through Mr. Chief Justice Narvasa, we ruled:

To begin with, there is no question of the right, in principle, of a consignee in a bill of lading to recover from the

carrier or shipper for loss of, or damage to goods being transported under said bill, although that document

may have been- as in practice it oftentimes is-drawn up only by the consignor and the carrierwithout the

intervention of the consignee. x x x.

x x x the right of a party in the same situation as respondent here, to recover for loss of a shipment

consigned to him under a bill of lading drawn up only by and between the shipper and the carrier,

springs from either a relation of agency that may exist between him and the shipper or consignor, or his

status as stranger in whose favor some stipulation is made in said contract, and who becomes a party

thereto when he demands fulfillment of that stipulation, in this case the delivery of the goods or cargo

shipped. In neither capacity can he assert personally, in bar to any provision of the bill of lading, the

alleged circumstance that fair and free agreement to such provision was vitiated by its being in such fine

print as to be hardly readable. Parenthetically, it may be observed that in one comparatively recent case

(Phoenix Assurance Company vs. Macondray & Co., Inc., 64 SCRA 15) where this Court found that a similar

package limitation clause was printed in the smallest type on the back of the bill of lading, it

nonetheless ruled that the consignee was bound thereby on the strength of authority holding that such

provisions on liability limitation are as much a part of a bill of lading as though physically in it and as

though placed therein by agreement of the parties.

There can, therefore, be no doubt or equivocation about the validity and enforceability of freely-agreed-upon

stipulations in a contract of carriage or bill of lading limiting the liability of the carrier to an agreed

valuation unless the shipper declares a higher value and inserts it into said contract or bill. This

proposition, moreover, rests upon an almost uniform weight of authority. (Underscoring supplied)

When private respondent formally claimed reimbursement for the missing goods from petitioner and subsequently

filed a case against the latter based on the very same bill of lading, it (private respondent) accepted the provisions of the

contract and thereby made itself a party thereto, or at least has come to court to enforce it.

[9]

Thus, private respondent

cannot now reject or disregard the carriers limited liability stipulation in the bill of lading. In other words, private

respondent is bound by the whole stipulations in the bill of lading and must respect the same.

Private respondent, however, insists that the carrier should be liable for the full value of the lost cargo in the amount

of Y1,552,500.00, considering that the shipper, Maruman Trading, had "fully declared the shipment x x x, the contents of

each crate, the dimensions, weight and value of the contents,"

[10]

as shown in the commercial Invoice No. MTM-941.

This claim was denied by petitioner, contending that it did not know of the contents, quantity and value of "the

shipment which consisted of three pre-packed crates described in Bill of Lading No. NGO-53MN merely as 3 CASES

SPARE PARTS.

[11]

The bill of lading in question confirms petitioners contention. To defeat the carriers limited liability, the aforecited

Clause 18 of the bill of lading requires that the shipper should have declared in writing a higher valuation of its goods

before receipt thereof by the carrier and insert the said declaration in the bill of lading, with the extra freight

paid. These requirements in the bill of lading were never complied with by the shipper, hence, the liability of the carrier

under the limited liability clause stands. The commercial Invoice No. MTM-941 does not in itself sufficiently and

convincingly show that petitioner has knowledge of the value of the cargo as contended by private respondent. No other

evidence was proffered by private respondent to support is contention. Thus, we are convinced that petitioner should be

liable for the full value of the lost cargo.

In fine, the liability of petitioner for the loss of the cargo is limited to One Hundred Thousand (Y100,000.00) Yen,

pursuant to Clause 18 of the bill of lading.

WHEREFORE, the decision of the Court of Appeals dated June 14, 1995 in C.A.-G.R. CV No. 42803 is hereby

REVERSED and SET ASIDE.

SO ORDERED.

2. MOF COMPANY, INC., vs.

SHIN YANG BROKERAGE

CORPORATION,

DEL CASTILLO, J .:

The necessity of proving lies with the person who sues.

The refusal of the consignee named in the bill of lading to pay the freightage on the claim that it is not privy to the contract of

affreightment propelled the shipper to sue for collection of money, stressing that its sole evidence, the bill of lading, suffices to prove

that the consignee is bound to pay. Petitioner now comes to us by way of Petition for Review on Certiorari

[1]

under Rule 45 praying for

the reversal of the Court of Appeals' (CA) judgment that dismissed its action for sum of money for insufficiency of evidence.

Factual Antecedents

On October 25, 2001, Halla Trading Co., a company based in Korea, shipped to Manila secondhand cars and other articles

on board the vessel HanjinBusan 0238W. The bill of lading covering the shipment, i.e., Bill of Lading No.

HJSCPUSI14168303,

[2]

which was prepared by the carrier Hanjin Shipping Co., Ltd. (Hanjin), named respondent Shin Yang

Brokerage Corp. (Shin Yang) as the consignee and indicated that payment was on a Freight Collect basis, i.e., that the

consignee/receiver of the goods would be the one to pay for the freight and other charges in the total amount of P57,646.00.

[3]

The shipment arrived in Manila on October 29, 2001. Thereafter, petitioner MOF Company, Inc. (MOF), Hanjins exclusive

general agent in thePhilippines, repeatedly demanded the payment of ocean freight, documentation fee and terminal handling

charges from Shin Yang. The latter, however, failed and refused to pay contending that it did not cause the importation of the goods,

that it is only the Consolidator of the said shipment, that the ultimate consignee did not endorse in its favor the original bill of lading and

that the bill of lading was prepared without its consent.

Thus, on March 19, 2003, MOF filed a case for sum of money before the Metropolitan Trial Court of Pasay City (MeTC Pasay)

which was docketed as Civil Case No. 206-03 and raffled to Branch 48. MOF alleged that Shin Yang, a regular client, caused the

importation and shipment of the goods and assured it that ocean freight and other charges would be paid upon arrival of the goods

in Manila. Yet, after Hanjin's compliance, Shin Yang unjustly breached its obligation to pay. MOF argued that Shin Yang, as the

named consignee in the bill of lading, entered itself as a party to the contract and bound itself to the Freight Collect

arrangement. MOF thus prayed for the payment of P57,646.00 representing ocean freight, documentation fee and terminal handling

charges as well as damages and attorneys fees.

Claiming that it is merely a consolidator/forwarder and that Bill of Lading No. HJSCPUSI14168303 was not endorsed to it by

the ultimate consignee, Shin Yang denied any involvement in shipping the goods or in promising to shoulder the freightage. It

asserted that it never authorized Halla Trading Co. to ship the articles or to have its name included in the bill of lading. Shin Yang also

alleged that MOF failed to present supporting documents to prove that it was Shin Yang that caused the importation or the one that

assured payment of the shipping charges upon arrival of the goods in Manila.

Ruling of the Metropolitan Trial Court

On June 16, 2004, the MeTC of Pasay City, Branch 48 rendered its Decision

[4]

in favor of MOF. It ruled that Shin Yang cannot

disclaim being a party to the contract of affreightment because:

x x x it would appear that defendant has business transactions with plaintiff. This is evident from defendants

letters dated 09 May 2002 and 13 May 2002 (Exhibits 1 and 2, defendants Position Paper) where it requested

for the release of refund of container deposits x x x. [In] the mind of the Court, by analogy, a written contract need

not be necessary; a mutual understanding [would suffice]. Further, plaintiff would have not included the name of the

defendant in the bill of lading, had there been no prior agreement to that effect.

In sum, plaintiff has sufficiently proved its cause of action against the defendant and the latter is obliged to

honor its agreement with plaintiff despite the absence of a written contract.

[5]

The dispositive portion of the MeTC Decision reads:

WHEREFORE, premises considered, judgment is hereby rendered in favor of plaintiff and against the

defendant, ordering the latter to pay plaintiff as follows:

1. P57,646.00 plus legal interest from the date of demand until fully paid,

2. P10,000.00 as and for attorneys fees and

3. the cost of suit.

SO ORDERED.

[6]

Ruling of the Regional Trial Court

The Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Pasay City, Branch 108 affirmed in toto the Decision of the MeTC. It held that:

MOF and Shin Yang entered into a contract of affreightment which Blacks Law Dictionary defined as a

contract with the ship owner to hire his ship or part of it, for the carriage of goods and generally take the form either

of a charter party or a bill of lading.

The bill of lading contain[s] the information embodied in the contract.

Article 652 of the Code of Commerce provides that the charter party must be in writing; however, Article

653 says: If the cargo should be received without charter party having been signed, the contract shall be

understood as executed in accordance with what appears in the bill of lading, the sole evidence of title with regard to

the cargo for determining the rights and obligations of the ship agent, of the captain and of the charterer. Thus, the

Supreme Court opined in the Market Developers, Inc. (MADE) vs. Honorable Intermediate Appellate Court and

Gaudioso Uy, G.R. No. 74978, September 8, 1989, this kind of contract may be oral. In another case, Compania

Maritima vs. Insurance Company of North America, 12 SCRA 213 the contract of affreightment by telephone was

recognized where the oral agreement was later confirmed by a formal booking.

x x x x

Defendant is liable to pay the sum of P57,646.00, with interest until fully paid, attorneys fees of P10,000.00

[and] cost of suit.

Considering all the foregoing, this Court affirms in toto the decision of the Court a quo.

SO ORDERED.

[7]

Ruling of the Court of Appeals

Seeing the matter in a different light, the CA dismissed MOFs complaint and refused to award any form of damages or

attorneys fees. It opined that MOF failed to substantiate its claim that Shin Yang had a hand in the importation of the articles to

the Philippines or that it gave its consent to be a consignee of the subject goods. In its March 22, 2006 Decision,

[8]

the CA said:

This Court is persuaded [that except] for the Bill of Lading, respondent has not presented any other evidence

to bolster its claim that petitioner has entered [into] an agreement of affreightment with respondent, be it verbal or

written. It is noted that the Bill of Lading was prepared by Hanjin Shipping, not the petitioner. Hanjin is the principal

while respondent is the formers agent. (p. 43, rollo)

The conclusion of the court a quo, which was upheld by the RTC Pasay City, Branch 108 xxx is purely

speculative and conjectural. A court cannot rely on speculations, conjectures or guesswork, but must depend upon

competent proof and on the basis of the best evidence obtainable under the circumstances. Litigation cannot be

properly resolved by suppositions, deductions or even presumptions, with no basis in evidence, for the truth must

have to be determined by the hard rules of admissibility and proof (Lagon vs. Hooven Comalco Industries, Inc. 349

SCRA 363).

While it is true that a bill of lading serves two (2) functions: first, it is a receipt for the goods shipped;

second, it is a contract by which three parties, namely, the shipper, the carrier and the consignee who undertake

specific responsibilities and assume stipulated obligations (Belgian Overseas Chartering and Shipping N.V. vs. Phil.

First Insurance Co., Inc., 383 SCRA 23), x x x if the same is not accepted, it is as if one party does not accept the

contract. Said the Supreme Court:

A bill of lading delivered and accepted constitutes the contract of carriage[,] even though

not signed, because the acceptance of a paper containing the terms of a proposed contract

generally constitutes an acceptance of the contract and of all its terms and conditions of which the

acceptor has actual or constructive notice (Keng Hua Paper Products Co., Inc. vs. CA, 286

SCRA 257).

In the present case, petitioner did not only [refuse to] accept the bill of lading, but it likewise disown[ed] the

shipment x x x. [Neither did it] authorize Halla Trading Company or anyone to ship or export the same on its behalf.

It is settled that a contract is upheld as long as there is proof of consent, subject matter and cause (Sta.

Clara Homeowners Association vs. Gaston, 374 SCRA 396). In the case at bar, there is not even any iota of

evidence to show that petitioner had given its consent.

He who alleges a fact has the burden of proving it and a mere allegation is not

evidence (Luxuria Homes Inc. vs. CA, 302 SCRA 315).

The 40-footer van contains goods of substantial value. It is highly improbable for petitioner not to pay the

charges, which is very minimal compared with the value of the goods, in order that it could work on the release

thereof.

For failure to substantiate its claim by preponderance of evidence, respondent has not established its case

against petitioner.

[9]

Petitioners filed a motion for reconsideration but it was denied in a Resolution

[10]

dated May 25, 2006. Hence, this petition for

review on certiorari.

Petitioners Arguments

In assailing the CAs Decision, MOF argues that the factual findings of both the MeTC and RTC are entitled to great weight and

respect and should have bound the CA. It stresses that the appellate court has no justifiable reason to disturb the lower courts

judgments because their conclusions are well-supported by the evidence on record.

MOF further argues that the CA erred in labeling the findings of the lower courts as purely speculative and

conjectural. According to MOF, the bill of lading, which expressly stated Shin Yang as the consignee, is the best evidence of the

latters actual participation in the transportation of the goods. Such document, validly entered, stands as the law among the shipper,

carrier and the consignee, who are all bound by the terms stated therein. Besides, a carriers valid claim after it fulfilled its obligation

cannot just be rejected by the named consignee upon a simple denial that it ever consented to be a party in a contract of

affreightment, or that it ever participated in the preparation of the bill of lading. As against Shin Yangs bare denials, the bill of lading is

the sufficient preponderance of evidence required to prove MOFs claim. MOF maintains that Shin Yang was the one that supplied all

the details in the bill of lading and acquiesced to be named consignee of the shipment on a Freight Collect basis.

Lastly, MOF claims that even if Shin Yang never gave its consent, it cannot avoid its obligation to pay, because it never

objected to being named as the consignee in the bill of lading and that it only protested when the shipment arrived in the Philippines,

presumably due to a botched transaction between it and Halla Trading Co. Furthermore, Shin Yangs letters asking for the refund of

container deposits highlight the fact that it was aware of the shipment and that it undertook preparations for the intended release of the

shipment.

Respondents Arguments

Echoing the CA decision, Shin Yang insists that MOF has no evidence to prove that it consented to take part in the contract of

affreightment. Shin Yang argues that MOF miserably failed to present any evidence to prove that it was the one that made

preparations for the subject shipment, or that it is an actual shipping practice that forwarders/consolidators as consignees are the

ones that provide carriers details and information on the bills of lading.

Shin Yang contends that a bill of lading is essentially a contract between the shipper and the carrier and ordinarily, the

shipper is the one liable for the freight charges. A consignee, on the other hand, is initially a stranger to the bill of lading and can be

liable only when the bill of lading specifies that the charges are to be paid by the consignee. This liability arises from either a) the

contract of agency between the shipper/consignor and the consignee; or b) the consignees availment of the stipulation pour

autrui drawn up by and between the shipper/ consignor and carrier upon the consignees demand that the goods be delivered to

it. Shin Yang contends that the fact that its name was mentioned as the consignee of the cargoes did not make it automatically liable

for the freightage because it never benefited from the shipment. It never claimed or accepted the goods, it was not the shippers

agent, it was not aware of its designation as consignee and the original bill of lading was never endorsed to it.

Issue

The issue for resolution is whether a consignee, who is not a signatory to the bill of lading, is bound by the stipulations

thereof. Corollarily, whether respondent who was not an agent of the shipper and who did not make any demand for the fulfillment of

the stipulations of the bill of lading drawn in its favor is liable to pay the corresponding freight and handling charges.

Our Ruling

Since the CA and the trial courts arrived at different conclusions, we are constrained to depart from the general rule that only

errors of law may be raised in a Petition for Review on Certiorari under Rule 45 of the Rules of Court and will review the evidence

presented.

[11]

The bill of lading is oftentimes drawn up by the shipper/consignor and the carrier without the intervention of the

consignee. However, the latter can be bound by the stipulations of the bill of lading when a) there is a relation of agency between the

shipper or consignor and the consignee or b) when the consignee demands fulfillment of the stipulation of the bill of lading which was

drawn up in its favor.

[12]

In Keng Hua Paper Products Co., Inc. v. Court of Appeals,

[13]

we held that once the bill of lading is received by the consignee

who does not object to any terms or stipulations contained therein, it constitutes as an acceptance of the contract and of all of its terms

and conditions, of which the acceptor has actual or constructive notice.

In Mendoza v. Philippine Air Lines, Inc.,

[14]

the consignee sued the carrier for damages but nevertheless claimed that he was

never a party to the contract of transportation and was a complete stranger thereto. In debunking Mendozas contention, we held that:

x x x First, he insists that the articles of the Code of Commerce should be applied; that he invokes the

provisions of said Code governing the obligations of a common carrier to make prompt delivery of goods given to it

under a contract of transportation. Later, as already said, he says that he was never a party to the contract of

transportation and was a complete stranger to it, and that he is now suing on a tort or a violation of his rights as a

stranger (culpa aquiliana). If he does not invoke the contract of carriage entered into with the defendant company,

then he would hardly have any leg to stand on. His right to prompt delivery of the can of film at the Pili AirPort stems

and is derived from the contract of carriage under which contract, the PAL undertook to carry the can of film safely

and to deliver it to him promptly. Take away or ignore that contract and the obligation to carry and to deliver and right

to prompt delivery disappear. Common carriers are not obligated by law to carry and to deliver merchandise, and

persons are not vested with the right to prompt delivery, unless such common carriers previously assume the

obligation. Said rights and obligations are created by a specific contract entered into by the parties. In the present

case, the findings of the trial court which as already stated, are accepted by the parties and which we must

accept are to the effect that the LVN Pictures Inc. and Jose Mendoza on one side, and the defendant

company on the other, entered into a contract of transportation (p. 29, Rec. on Appeal). One interpretation

of said finding is that the LVN Pictures Inc. through previous agreement with Mendozaacted as the latter's

agent. When he negotiated with the LVN Pictures Inc. to rent the film 'Himala ng Birhen' and show it during

the Naga town fiesta, he most probably authorized and enjoined the Picture Company to ship the film for

him on the PAL on September 17th. Another interpretation is that even if the LVN Pictures Inc. as

consignor of its own initiative, and acting independently of Mendoza for the time being, made Mendoza a

consignee. [Mendoza made himself a party to the contract of transportaion when he appeared at the Pili

Air Port armed with the copy of the Air Way Bill (Exh. 1) demanding the delivery of the shipment to him.]

The very citation made by appellant in his memorandum supports this view. Speaking of the possibility of a conflict

between the order of the shipper on the one hand and the order of the consignee on the other, as when the shipper

orders the shipping company to return or retain the goods shipped while the consignee demands their delivery,

Malagarriga in his book Codigo de Comercio Comentado, Vol. 1, p. 400, citing a decision of the Argentina Court of

Appeals on commercial matters, cited by Tolentino in Vol. II of his book entitled 'Commentaries and Jurisprudence

on the Commercial Laws of the Philippines' p. 209, says that the right of the shipper to countermand the

shipment terminates when the consignee or legitimate holder of the bill of lading appears with such bill of

lading before the carrier and makes himself a party to the contract. Prior to that time he is a stranger to the

contract.

Still another view of this phase of the case is that contemplated in Art. 1257, paragraph 2, of the old

Civil Code (now Art. 1311, second paragraph) which reads thus:

Should the contract contain any stipulation in favor of a third person, he may

demand its fulfillment provided he has given notice of his acceptance to the person bound

before the stipulation has been revoked.'

Here, the contract of carriage between the LVN Pictures Inc. and the defendant carrier contains the

stipulations of delivery to Mendoza as consignee. His demand for the delivery of the can of film to him at

the Pili Air Port may be regarded as a notice of his acceptance of the stipulation of the delivery in his favor

contained in the contract of carriage and delivery. In this case he also made himself a party to the contract,

or at least has come to court to enforce it. His cause of action must necessarily be founded on its

breach.

[15]

(Emphasis Ours)

In sum, a consignee, although not a signatory to the contract of carriage between the shipper and the carrier, becomes a

party to the contract by reason of either a) the relationship of agency between the consignee and the shipper/ consignor; b) the

unequivocal acceptance of the bill of lading delivered to the consignee, with full knowledge of its contents or c) availment of the

stipulation pour autrui, i.e., when the consignee, a third person, demands before the carrier the fulfillment of the stipulation made by

the consignor/shipper in the consignees favor, specifically the delivery of the goods/cargoes shipped.

[16]

In the instant case, Shin Yang consistently denied in all of its pleadings that it authorized Halla Trading, Co. to ship the goods

on its behalf; or that it got hold of the bill of lading covering the shipment or that it demanded the release of the cargo. Basic is the rule

in evidence that the burden of proof lies upon him who asserts it, not upon him who denies, since, by the nature of things, he who

denies a fact cannot produce any proof of it.

[17]

Thus, MOF has the burden to controvert all these denials, it being insistent that Shin

Yang asserted itself as the consignee and the one that caused the shipment of the goods to the Philippines.

In civil cases, the party having the burden of proof must establish his case by preponderance of evidence,

[18]

which means

evidence which is of greater weight, or more convincing than that which is offered in opposition to it.

[19]

Here, MOF failed to meet the

required quantum of proof. Other than presenting the bill of lading, which, at most, proves that the carrier acknowledged receipt of the

subject cargo from the shipper and that the consignee named is to shoulder the freightage, MOF has not adduced any other credible

evidence to strengthen its cause of action. It did not even present any witness in support of its allegation that it was Shin Yang which

furnished all the details indicated in the bill of lading and that Shin Yang consented to shoulder the shipment costs. There is also

nothing in the records which would indicate that Shin Yang was an agent of Halla Trading Co. or that it exercised any act that would

bind it as a named consignee. Thus, the CA correctly dismissed the suit for failure of petitioner to establish its cause against

respondent.

WHEREFORE, the petition is DENIED. The assailed Decision of the Court of Appeals dated March 22, 2006 dismissing

petitioners complaint and the Resolution dated May 25, 2006 denying the motion for reconsideration are AFFIRMED.

SO ORDERED.

3. G.R. No. 95582 October 7, 1991

DANGWA TRANSPORTATION CO., INC.vs. COURT OF APPEALS

REGALADO, J .:p

On May 13, 1985, private respondents filed a complaint 1 for damages against petitioners for the death of Pedrito

Cudiamat as a result of a vehicular accident which occurred on March 25, 1985 at Marivic, Sapid, Mankayan, Benguet.

Among others, it was alleged that on said date, while petitioner Theodore M. Lardizabal was driving a passenger bus

belonging to petitioner corporation in a reckless and imprudent manner and without due regard to traffic rules and

regulations and safety to persons and property, it ran over its passenger, Pedrito Cudiamat. However, instead of bringing

Pedrito immediately to the nearest hospital, the said driver, in utter bad faith and without regard to the welfare of the

victim, first brought his other passengers and cargo to their respective destinations before banging said victim to the

Lepanto Hospital where he expired.

On the other hand, petitioners alleged that they had observed and continued to observe the extraordinary diligence

required in the operation of the transportation company and the supervision of the employees, even as they add that they

are not absolute insurers of the safety of the public at large. Further, it was alleged that it was the victim's own

carelessness and negligence which gave rise to the subject incident, hence they prayed for the dismissal of the complaint

plus an award of damages in their favor by way of a counterclaim.

On July 29, 1988, the trial court rendered a decision, effectively in favor of petitioners, with this decretal portion:

IN VIEW OF ALL THE FOREGOING, judgment is hereby pronounced that Pedrito Cudiamat was

negligent, which negligence was the proximate cause of his death. Nonetheless, defendants in equity, are

hereby ordered to pay the heirs of Pedrito Cudiamat the sum of P10,000.00 which approximates the

amount defendants initially offered said heirs for the amicable settlement of the case. No costs.

SO ORDERED. 2

Not satisfied therewith, private respondents appealed to the Court of Appeals which, in a decision 3 in CA-G.R. CV No.

19504 promulgated on August 14, 1990, set aside the decision of the lower court, and ordered petitioners to pay private

respondents:

1. The sum of Thirty Thousand (P30,000.00) Pesos by way of indemnity for death of the victim Pedrito

Cudiamat;

2. The sum of Twenty Thousand (P20,000.00) by way of moral damages;

3. The sum of Two Hundred Eighty Eight Thousand (P288,000.00) Pesos as actual and compensatory

damages;

4. The costs of this suit. 4

Petitioners' motion for reconsideration was denied by the Court of Appeals in its resolution dated October 4,

1990, 5 hence this petition with the central issue herein being whether respondent court erred in reversing the decision of

the trial court and in finding petitioners negligent and liable for the damages claimed.

It is an established principle that the factual findings of the Court of Appeals as a rule are final and may not be reviewed

by this Court on appeal. However, this is subject to settled exceptions, one of which is when the findings of the appellate

court are contrary to those of the trial court, in which case a reexamination of the facts and evidence may be

undertaken. 6

In the case at bar, the trial court and the Court of Appeal have discordant positions as to who between the petitioners an

the victim is guilty of negligence. Perforce, we have had to conduct an evaluation of the evidence in this case for the

prope calibration of their conflicting factual findings and legal conclusions.

The lower court, in declaring that the victim was negligent, made the following findings:

This Court is satisfied that Pedrito Cudiamat was negligent in trying to board a moving vehicle, especially

with one of his hands holding an umbrella. And, without having given the driver or the conductor any

indication that he wishes to board the bus. But defendants can also be found wanting of the necessary

diligence. In this connection, it is safe to assume that when the deceased Cudiamat attempted to board

defendants' bus, the vehicle's door was open instead of being closed. This should be so, for it is hard to

believe that one would even attempt to board a vehicle (i)n motion if the door of said vehicle is closed.

Here lies the defendant's lack of diligence. Under such circumstances, equity demands that there must be

something given to the heirs of the victim to assuage their feelings. This, also considering that initially,

defendant common carrier had made overtures to amicably settle the case. It did offer a certain monetary

consideration to the victim's heirs. 7

However, respondent court, in arriving at a different opinion, declares that:

From the testimony of appellees'own witness in the person of Vitaliano Safarita, it is evident that the

subject bus was at full stop when the victim Pedrito Cudiamat boarded the same as it was precisely on

this instance where a certain Miss Abenoja alighted from the bus. Moreover, contrary to the assertion of

the appellees, the victim did indicate his intention to board the bus as can be seen from the testimony of

the said witness when he declared that Pedrito Cudiamat was no longer walking and made a sign to

board the bus when the latter was still at a distance from him. It was at the instance when Pedrito

Cudiamat was closing his umbrella at the platform of the bus when the latter made a sudden jerk

movement (as) the driver commenced to accelerate the bus.

Evidently, the incident took place due to the gross negligence of the appellee-driver in prematurely

stepping on the accelerator and in not waiting for the passenger to first secure his seat especially so

when we take into account that the platform of the bus was at the time slippery and wet because of a

drizzle. The defendants-appellees utterly failed to observe their duty and obligation as common carrier to

the end that they should observe extra-ordinary diligence in the vigilance over the goods and for the

safety of the passengers transported by them according to the circumstances of each case (Article 1733,

New Civil Code). 8

After a careful review of the evidence on record, we find no reason to disturb the above holding of the Court of Appeals.

Its aforesaid findings are supported by the testimony of petitioners' own witnesses. One of them, Virginia Abalos, testified

on cross-examination as follows:

Q It is not a fact Madam witness, that at bunkhouse 54, that is before the place of the

incident, there is a crossing?

A The way going to the mines but it is not being pass(ed) by the bus.

Q And the incident happened before bunkhouse 56, is that not correct?

A It happened between 54 and 53 bunkhouses. 9

The bus conductor, Martin Anglog, also declared:

Q When you arrived at Lepanto on March 25, 1985, will you please inform this Honorable

Court if there was anv unusual incident that occurred?

A When we delivered a baggage at Marivic because a person alighted there between

Bunkhouse 53 and 54.

Q What happened when you delivered this passenger at this particular place in Lepanto?

A When we reached the place, a passenger alighted and I signalled my driver. When we

stopped we went out because I saw an umbrella about a split second and I signalled

again the driver, so the driver stopped and we went down and we saw Pedrito Cudiamat

asking for help because he was lying down.

Q How far away was this certain person, Pedrito Cudiamat, when you saw him lying

down from the bus how far was he?

A It is about two to three meters.

Q On what direction of the bus was he found about three meters from the bus, was it at

the front or at the back?

A At the back, sir. 10 (Emphasis supplied.)

The foregoing testimonies show that the place of the accident and the place where one of the passengers alighted were

both between Bunkhouses 53 and 54, hence the finding of the Court of Appeals that the bus was at full stop when the

victim boarded the same is correct. They further confirm the conclusion that the victim fell from the platform of the bus

when it suddenly accelerated forward and was run over by the rear right tires of the vehicle, as shown by the physical

evidence on where he was thereafter found in relation to the bus when it stopped. Under such circumstances, it cannot be

said that the deceased was guilty of negligence.

The contention of petitioners that the driver and the conductor had no knowledge that the victim would ride on the bus,

since the latter had supposedly not manifested his intention to board the same, does not merit consideration. When the

bus is not in motion there is no necessity for a person who wants to ride the same to signal his intention to board. A public

utility bus, once it stops, is in effect making a continuous offer to bus riders. Hence, it becomes the duty of the driver and

the conductor, every time the bus stops, to do no act that would have the effect of increasing the peril to a passenger

while he was attempting to board the same. The premature acceleration of the bus in this case was a breach of such

duty. 11

It is the duty of common carriers of passengers, including common carriers by railroad train, streetcar, or motorbus, to

stop their conveyances a reasonable length of time in order to afford passengers an opportunity to board and enter, and

they are liable for injuries suffered by boarding passengers resulting from the sudden starting up or jerking of their

conveyances while they are doing so. 12

Further, even assuming that the bus was moving, the act of the victim in boarding the same cannot be considered

negligent under the circumstances. As clearly explained in the testimony of the aforestated witness for petitioners, Virginia

Abalos, th bus had "just started" and "was still in slow motion" at the point where the victim had boarded and was on its

platform. 13

It is not negligence per se, or as a matter of law, for one attempt to board a train or streetcar which is moving

slowly. 14 An ordinarily prudent person would have made the attempt board the moving conveyance under the same or

similar circumstances. The fact that passengers board and alight from slowly moving vehicle is a matter of common

experience both the driver and conductor in this case could not have been unaware of such an ordinary practice.

The victim herein, by stepping and standing on the platform of the bus, is already considered a passenger and is entitled

all the rights and protection pertaining to such a contractual relation. Hence, it has been held that the duty which the

carrier passengers owes to its patrons extends to persons boarding cars as well as to those alighting therefrom. 15

Common carriers, from the nature of their business and reasons of public policy, are bound to observe extraordina

diligence for the safety of the passengers transported by the according to all the circumstances of each case. 16 A

common carrier is bound to carry the passengers safely as far as human care and foresight can provide, using the utmost

diligence very cautious persons, with a due regard for all the circumstances. 17

It has also been repeatedly held that in an action based on a contract of carriage, the court need not make an express

finding of fault or negligence on the part of the carrier in order to hold it responsible to pay the damages sought by the

passenger. By contract of carriage, the carrier assumes the express obligation to transport the passenger to his

destination safely and observe extraordinary diligence with a due regard for all the circumstances, and any injury that

might be suffered by the passenger is right away attributable to the fault or negligence of the carrier. This is an exception

to the general rule that negligence must be proved, and it is therefore incumbent upon the carrier to prove that it has

exercised extraordinary diligence as prescribed in Articles 1733 and 1755 of the Civil Code. 18

Moreover, the circumstances under which the driver and the conductor failed to bring the gravely injured victim

immediately to the hospital for medical treatment is a patent and incontrovertible proof of their negligence. It defies

understanding and can even be stigmatized as callous indifference. The evidence shows that after the accident the bus

could have forthwith turned at Bunk 56 and thence to the hospital, but its driver instead opted to first proceed to Bunk 70

to allow a passenger to alight and to deliver a refrigerator, despite the serious condition of the victim. The vacuous reason

given by petitioners that it was the wife of the deceased who caused the delay was tersely and correctly confuted by

respondent court:

... The pretension of the appellees that the delay was due to the fact that they had to wait for about twenty

minutes for Inocencia Cudiamat to get dressed deserves scant consideration. It is rather scandalous and

deplorable for a wife whose husband is at the verge of dying to have the luxury of dressing herself up for

about twenty minutes before attending to help her distressed and helpless husband. 19

Further, it cannot be said that the main intention of petitioner Lardizabal in going to Bunk 70 was to inform the victim's

family of the mishap, since it was not said bus driver nor the conductor but the companion of the victim who informed his

family thereof. 20 In fact, it was only after the refrigerator was unloaded that one of the passengers thought of sending

somebody to the house of the victim, as shown by the testimony of Virginia Abalos again, to wit:

Q Why, what happened to your refrigerator at that particular time?

A I asked them to bring it down because that is the nearest place to our house and when

I went down and asked somebody to bring down the refrigerator, I also asked somebody

to call the family of Mr. Cudiamat.

COURT:

Q Why did you ask somebody to call the family of Mr. Cudiamat?

A Because Mr. Cudiamat met an accident, so I ask somebody to call for the family of Mr.

Cudiamat.

Q But nobody ask(ed) you to call for the family of Mr. Cudiamat?

A No sir. 21

With respect to the award of damages, an oversight was, however, committed by respondent Court of Appeals in

computing the actual damages based on the gross income of the victim. The rule is that the amount recoverable by the

heirs of a victim of a tort is not the loss of the entire earnings, but rather the loss of that portion of the earnings which the

beneficiary would have received. In other words, only net earnings, not gross earnings, are to be considered, that is, the

total of the earnings less expenses necessary in the creation of such earnings or income and minus living and other

incidental expenses. 22

We are of the opinion that the deductible living and other expense of the deceased may fairly and reasonably be fixed at

P500.00 a month or P6,000.00 a year. In adjudicating the actual or compensatory damages, respondent court found that

the deceased was 48 years old, in good health with a remaining productive life expectancy of 12 years, and then earning

P24,000.00 a year. Using the gross annual income as the basis, and multiplying the same by 12 years, it accordingly

awarded P288,000. Applying the aforestated rule on computation based on the net earnings, said award must be, as it

hereby is, rectified and reduced to P216,000.00. However, in accordance with prevailing jurisprudence, the death

indemnity is hereby increased to P50,000.00. 23

WHEREFORE, subject to the above modifications, the challenged judgment and resolution of respondent Court of

Appeals are hereby AFFIRMED in all other respects.

SO ORDERED.

4. KOREAN AIRLINES CO., LTD. vs. COURT OF APPEALS and JUANITO C. LAPUZ

G.R. No. 113842 August 23, 1995

JUANITO C. LAPUZ, petitioner, vs.COURT OF APPEALS and KOREAN AIRLINES CO., LTD., respondents.

FRANCISCO, J .:

The case is of 1980 vintage. It originated from the Regional Trial Court, appealed to the Court of Appeals, then finally

elevated to this Court. From the Court's disposition of the case stemmed incidents which are now the subjects for

resolution. To elaborate:

In an action for breach of contract of carriage, Korean Airlines, Co., Ltd., (KAL) was ordered by the trial court to pay

actual/compensatory damages, with legal interest, attorney's fees and costs of suit in favor of plaintiff Juanito C.

Lapuz.

1

Both parties appealed to the Court of Appeals, but the trial court's judgment was merely modified: the award of

compensatory damages reduced, an award for moral and exemplary damages added, with 6% interest per annum from

the date of filing of the complaint, and the attorney's fees and costs deleted.

The parties subsequently elevated the case to this Court, docketed as G.R. No. 114061 and G.R. No. 113842. On August

3, 1994, the Court in a consolidated decision affirmed the decision of the Court of Appeals, modified only as to the

commencement date of the award of legal interest, i.e., from the date of the decision of the trial court and not from the

date of filing of the complaint.

2

The parties filed their respective motions for reconsideration with KAL, for the first time,

assailing the Court's lack of jurisdiction to impose legal interest as the complaint allegedly failed to pray for its award. In a

resolution dated September 21, 1994, the Court resolved to deny both motions for reconsideration with finality.

Notwithstanding, KAL filed subsequent pleadings asking for reconsideration of the Court's consolidated decision and

again impugning the award of legal interest. Lapuz, meanwhile, filed a motion for early resolution of the case followed by a

motion for execution dated March 14, 1995, praying for the issuance of a writ of execution. KAL, in response, filed its

Opposition and Supplemental Argument in Support of the Opposition dated March 28, 1995, and March 30, 1995,

respectively. Additionally, on May 3, 1995, Lapuz filed another Urgent Motion for Early Resolution stating that the case

has been pending for fifteen years which KAL admitted in its Comment filed two days later, albeit stressing that its

pleadings were not intended for delay.

3

KAL's asseveration that the Court lacks jurisdiction to award legal interest is devoid of merit. Both the complaint and

amended complaint against KAL dated November 27, 1980, and January 5, 1981, respectively, prayed for reliefs and

remedies to which Lapuz may be entitled in law and equity. The award of legal interest is one such relief, as it is based on

equitable grounds duly sanctioned by Article 2210 of the Civil Code which provides that: "[i]nterest may, in the discretion

of the Court, be allowed upon damages awarded for breach of contract".

4

Furthermore, in its petition for review before the Court of Appeals, KAL did not question the trial court's imposition of legal

interest. Likewise, in its appeal before the Court, KAL never bewailed the award of legal interest. In fact, KAL took

exception only with respect to the date when legal interest should commence to run.

5

Indeed, it was only in its motion for

reconsideration when suddenly its imposition was assailed for having been rendered without jurisdiction. To strengthen its

languid position, KAL's subsequent pleadings clothed its attack with constitutional import for alleged violation of its right to

due process. There is no cogent reason and none appears on record that could sustain KAL's scheme as KAL was amply

given, in the courts below and in this Court, occasion to ventilate its case. What is repugnant to due process is the denial

of opportunity to be heard

6

which opportunity KAL was extensively afforded. While it is a rule that jurisdictional question

may be raised at any time, this, however, admits of an exception where, as in this case, estoppel has supervened.

7

This

court has time and again frowned upon the undesirable practice of a party submitting his case for decision and then

accepting the judgment, only if favorable, and attacking it for lack of jurisdiction when adverse.

8

The Court shall not

countenance KAL's undesirable moves. What attenuates KAL's unmeritorious importuning is that the assailed decision

has long acquired finality. It is a settled rule that a judgment which has acquired finality becomes immutable and

unalterable, hence may no longer be modified in any respect except only to correct clerical errors or mistake.

9

Once a

judgment becomes final, all the issues between the parties are deemed resolved and laid to rest.

KAL's filing of numerous pleadings delayed the disposition of the case which for fifteen years remained pending. This

practice may constitute abuse of the Court's processes for it tends to impede, obstruct and degrade the administration of

justice. In Li Kim Tho v. Go Siu Ko, et al.,

10

the Court gave this reminder to litigants and lawyers' alike:

Litigation must end and terminate sometime and somewhere, and it is essential to an effective and

efficient administration of justice that, once a judgment has become final, the winning party be not,

through a mere subterfuge, deprived of the fruits of the verdict. Courts must therefore guard against any

scheme calculated to bring about the result. Constituted as they are to put an end to controversies, courts

should frown upon any attempt to prolong them.

11

Likewise, in Banogan v. Zerna

12

the Court reminded lawyers of their responsibility as officers of the court in this manner:

As officers of the court, lawyers have a responsibility to assist in the proper administration of justice. They

do not discharge this duty by filing pointless petitions that only add to the workload of the judiciary,

especially this Court, which is burdened enough as it is. A judicious study of the facts and the law should

advise them when a case, such as this, should not de permitted to be filed to merely clutter the already

congested judicial dockets. They do not advance the cause of law or their clients by commencing

litigations that for sheer lack of merit do not deserve the attention of the courts.

13

A lawyer owes fidelity to the cause of his client, but not at the expense of truth and the administration of justice.

14

Counsel

for KAL is reminded that it is his duty not to unduly delay a case, impede the execution of a judgment or misuse Court

processes.

15

With respect to Lapuz' motion for execution, suffice to state that the application for a writ of execution should be

addressed to the court of origin and not to this Court. As the judgment has become final and executory then all that is left

of the trial court is the ministerial act of ordering the execution thereof.

ACCORDINGLY, KAL's motion for reconsideration is DENlED. Counsel for KAL is hereby warned that repetition of his

undesirable practice shall be dealt with severely.

5. G.R. No. 145804 February 6, 2003

LIGHT RAIL TRANSIT AUTHORITY & RODOLFO ROMAN, petitioners,

vs.MARJORIE NAVIDAD, Heirs of the Late NICANOR NAVIDAD & PRUDENT SECURITY AGENCY,respondents.

VITUG, J .:

The case before the Court is an appeal from the decision and resolution of the Court of Appeals, promulgated on 27 April

2000 and 10 October 2000, respectively, in CA-G.R. CV No. 60720, entitled "Marjorie Navidad and Heirs of the Late

Nicanor Navidad vs. Rodolfo Roman, et. al.," which has modified the decision of 11 August 1998 of the Regional Trial

Court, Branch 266, Pasig City, exonerating Prudent Security Agency (Prudent) from liability and finding Light Rail Transit

Authority (LRTA) and Rodolfo Roman liable for damages on account of the death of Nicanor Navidad.

On 14 October 1993, about half an hour past seven oclock in the evening, Nicanor Navidad, then drunk, entered the

EDSA LRT station after purchasing a "token" (representing payment of the fare). While Navidad was standing on the

platform near the LRT tracks, Junelito Escartin, the security guard assigned to the area approached Navidad. A

misunderstanding or an altercation between the two apparently ensued that led to a fist fight. No evidence, however, was

adduced to indicate how the fight started or who, between the two, delivered the first blow or how Navidad later fell on the

LRT tracks. At the exact moment that Navidad fell, an LRT train, operated by petitioner Rodolfo Roman, was coming in.

Navidad was struck by the moving train, and he was killed instantaneously.

On 08 December 1994, the widow of Nicanor, herein respondent Marjorie Navidad, along with her children, filed a

complaint for damages against Junelito Escartin, Rodolfo Roman, the LRTA, the Metro Transit Organization, Inc. (Metro

Transit), and Prudent for the death of her husband. LRTA and Roman filed a counterclaim against Navidad and a cross-

claim against Escartin and Prudent. Prudent, in its answer, denied liability and averred that it had exercised due diligence

in the selection and supervision of its security guards.

The LRTA and Roman presented their evidence while Prudent and Escartin, instead of presenting evidence, filed a

demurrer contending that Navidad had failed to prove that Escartin was negligent in his assigned task. On 11 August

1998, the trial court rendered its decision; it adjudged:

"WHEREFORE, judgment is hereby rendered in favor of the plaintiffs and against the defendants Prudent Security and

Junelito Escartin ordering the latter to pay jointly and severally the plaintiffs the following:

"a) 1) Actual damages of P44,830.00;

2) Compensatory damages of P443,520.00;

3) Indemnity for the death of Nicanor Navidad in the sum of P50,000.00;

"b) Moral damages of P50,000.00;

"c) Attorneys fees of P20,000;

"d) Costs of suit.

"The complaint against defendants LRTA and Rodolfo Roman are dismissed for lack of merit.

"The compulsory counterclaim of LRTA and Roman are likewise dismissed."

1

Prudent appealed to the Court of Appeals. On 27 August 2000, the appellate court promulgated its now assailed decision

exonerating Prudent from any liability for the death of Nicanor Navidad and, instead, holding the LRTA and Roman jointly

and severally liable thusly:

"WHEREFORE, the assailed judgment is hereby MODIFIED, by exonerating the appellants from any liability for the death

of Nicanor Navidad, Jr. Instead, appellees Rodolfo Roman and the Light Rail Transit Authority (LRTA) are held liable for

his death and are hereby directed to pay jointly and severally to the plaintiffs-appellees, the following amounts:

a) P44,830.00 as actual damages;

b) P50,000.00 as nominal damages;

c) P50,000.00 as moral damages;

d) P50,000.00 as indemnity for the death of the deceased; and

e) P20,000.00 as and for attorneys fees."

2

The appellate court ratiocinated that while the deceased might not have then as yet boarded the train, a contract of

carriage theretofore had already existed when the victim entered the place where passengers were supposed to be after

paying the fare and getting the corresponding token therefor. In exempting Prudent from liability, the court stressed that

there was nothing to link the security agency to the death of Navidad. It said that Navidad failed to show that Escartin

inflicted fist blows upon the victim and the evidence merely established the fact of death of Navidad by reason of his

having been hit by the train owned and managed by the LRTA and operated at the time by Roman. The appellate court

faulted petitioners for their failure to present expert evidence to establish the fact that the application of emergency brakes

could not have stopped the train.

The appellate court denied petitioners motion for reconsideration in its resolution of 10 October 2000.

In their present recourse, petitioners recite alleged errors on the part of the appellate court; viz:

"I.

THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS GRAVELY ERRED BY DISREGARDING THE FINDINGS OF FACTS BY THE

TRIAL COURT

"II.

THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS GRAVELY ERRED IN FINDING THAT PETITIONERS ARE LIABLE FOR THE

DEATH OF NICANOR NAVIDAD, JR.

"III.

THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS GRAVELY ERRED IN FINDING THAT RODOLFO ROMAN IS AN

EMPLOYEE OF LRTA."

3

Petitioners would contend that the appellate court ignored the evidence and the factual findings of the trial court by

holding them liable on the basis of a sweeping conclusion that the presumption of negligence on the part of a common

carrier was not overcome. Petitioners would insist that Escartins assault upon Navidad, which caused the latter to fall on

the tracks, was an act of a stranger that could not have been foreseen or prevented. The LRTA would add that the

appellate courts conclusion on the existence of an employer-employee relationship between Roman and LRTA lacked

basis because Roman himself had testified being an employee of Metro Transit and not of the LRTA.

Respondents, supporting the decision of the appellate court, contended that a contract of carriage was deemed created

from the moment Navidad paid the fare at the LRT station and entered the premises of the latter, entitling Navidad to all

the rights and protection under a contractual relation, and that the appellate court had correctly held LRTA and Roman

liable for the death of Navidad in failing to exercise extraordinary diligence imposed upon a common carrier.

Law and jurisprudence dictate that a common carrier, both from the nature of its business and for reasons of public policy,

is burdened with the duty of exercising utmost diligence in ensuring the safety of passengers.

4

The Civil Code, governing

the liability of a common carrier for death of or injury to its passengers, provides:

"Article 1755. A common carrier is bound to carry the passengers safely as far as human care and foresight can provide,

using the utmost diligence of very cautious persons, with a due regard for all the circumstances.

"Article 1756. In case of death of or injuries to passengers, common carriers are presumed to have been at fault or to

have acted negligently, unless they prove that they observed extraordinary diligence as prescribed in articles 1733 and

1755."

"Article 1759. Common carriers are liable for the death of or injuries to passengers through the negligence or willful acts of

the formers employees, although such employees may have acted beyond the scope of their authority or in violation of

the orders of the common carriers.

"This liability of the common carriers does not cease upon proof that they exercised all the diligence of a good father of a

family in the selection and supervision of their employees."

"Article 1763. A common carrier is responsible for injuries suffered by a passenger on account of the willful acts or

negligence of other passengers or of strangers, if the common carriers employees through the exercise of the diligence of

a good father of a family could have prevented or stopped the act or omission."

The law requires common carriers to carry passengers safely using the utmost diligence of very cautious persons with

due regard for all circumstances.

5

Such duty of a common carrier to provide safety to its passengers so obligates it not

only during the course of the trip but for so long as the passengers are within its premises and where they ought to be in

pursuance to the contract of carriage.

6

The statutory provisions render a common carrier liable for death of or injury to

passengers (a) through the negligence or wilful acts of its employees or b) on account of wilful acts or negligence of other

passengers or of strangers if the common carriers employees through the exercise of due diligence could have prevented

or stopped the act or omission.

7

In case of such death or injury, a carrier is presumed to have been at fault or been

negligent, and

8

by simple proof of injury, the passenger is relieved of the duty to still establish the fault or negligence of

the carrier or of its employees and the burden shifts upon the carrier to prove that the injury is due to an unforeseen event

or to force majeure.

9

In the absence of satisfactory explanation by the carrier on how the accident occurred, which

petitioners, according to the appellate court, have failed to show, the presumption would be that it has been at fault,

10

an

exception from the general rule that negligence must be proved.

11

The foundation of LRTAs liability is the contract of carriage and its obligation to indemnify the victim arises from the

breach of that contract by reason of its failure to exercise the high diligence required of the common carrier. In the

discharge of its commitment to ensure the safety of passengers, a carrier may choose to hire its own employees or avail

itself of the services of an outsider or an independent firm to undertake the task. In either case, the common carrier is not

relieved of its responsibilities under the contract of carriage.

Should Prudent be made likewise liable? If at all, that liability could only be for tort under the provisions of Article

2176

12

and related provisions, in conjunction with Article 2180,

13

of the Civil Code. The premise, however, for the

employers liability is negligence or fault on the part of the employee. Once such fault is established, the employer can

then be made liable on the basis of the presumption juris tantum that the employer failed to exercise diligentissimi patris

families in the selection and supervision of its employees. The liability is primary and can only be negated by showing due

diligence in the selection and supervision of the employee, a factual matter that has not been shown. Absent such a

showing, one might ask further, how then must the liability of the common carrier, on the one hand, and an independent

contractor, on the other hand, be described? It would be solidary. A contractual obligation can be breached by tort and

when the same act or omission causes the injury, one resulting in culpa contractual and the other in culpa aquiliana,

Article 2194

14

of the Civil Code can well apply.

15

In fine, a liability for tort may arise even under a contract, where tort is

that which breaches the contract.

16

Stated differently, when an act which constitutes a breach of contract would have itself

constituted the source of a quasi-delictual liability had no contract existed between the parties, the contract can be said to

have been breached by tort, thereby allowing the rules on tort to apply.