Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

M.riendra Rahmatullah Jurnal 2

Caricato da

M RiendRa Rahmatullah Uslani0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

52 visualizzazioni10 pagineStudy conducted in four districts of the Upper East region of Ghana. Results showed that all kinds of highly hazardous, adulterated, and inappropriate chemical products are sold by dealers to farmers. Some of the agrochemical products the farmers currently use on their crops have been banned by the relevant government authorities.

Descrizione originale:

Titolo originale

21080112130041 M.riendra Rahmatullah Jurnal 2

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoStudy conducted in four districts of the Upper East region of Ghana. Results showed that all kinds of highly hazardous, adulterated, and inappropriate chemical products are sold by dealers to farmers. Some of the agrochemical products the farmers currently use on their crops have been banned by the relevant government authorities.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

52 visualizzazioni10 pagineM.riendra Rahmatullah Jurnal 2

Caricato da

M RiendRa Rahmatullah UslaniStudy conducted in four districts of the Upper East region of Ghana. Results showed that all kinds of highly hazardous, adulterated, and inappropriate chemical products are sold by dealers to farmers. Some of the agrochemical products the farmers currently use on their crops have been banned by the relevant government authorities.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 10

1

Volume 5, Issue 1, 2012

Dry-Season Farming and Agrochemical Misuse in Upper East Region of Ghana: Implication and

Way Forward

Joseph K. Laary, Lecturer, Department of Ecological Agriculture, Bolgatanga Polytechnic, jlaary@yahoo.co.uk

Abstract

This study was conducted in four districts of the Upper East region of Ghana to determine different agrochemical

products sold to farmers, and the extent to which farmers use them on their crops, especially during dry season.

The results showed that all kinds of highly hazardous, adulterated, and inappropriate chemical products are sold by

dealers to farmers. Some of the agrochemicals sold to farmers had their labels scraped off; some were expired,

while others had been transferred into different containers. Some of the agrochemical products the farmers

currently use on their crops have been banned by the relevant government authorities because of their persistent,

toxic, and poisonous nature. A good number of the farmers (74%) who buy the agrochemicals are illiterates, most

of who do not protect themselves, and are unaware of dangers of exposure during handling, formulation, and

application of agrochemicals. Fruits and vegetables are harvested within days after last agrochemical application,

regardless of health implications. Most of the farmers (89%) know only synthetic chemicals and the few who know

other alternatives do not see their importance or are not interested. There is therefore the need for farmer education

and participatory practices on safe usage of agrochemicals to safeguard humans, other beneficial life-forms, and

the environment.

Keywords: Farmer, Agrochemical misuse, Education, Participatory practices, Environment.

Introduction

The Upper East Region is located at the extreme north-eastern portion of Ghana. About 89% of its communities are

predominantly rural, with a population density of about 100 people/Km

2

area. Agriculture is the dominant economic

activity, employing 80% of the active population, who are mostly illiterates. The vegetation of the region is Guinea-

Savanna, with unimodal rainfall distribution, which gives a single 5-6 months rainy (growing) season between

April/May and September/October, and 6-7 months long dry season from October to April (MOFA, 2008).

The long dry season from October to April is associated with dry harmattan winds with low humidity and low night

temperatures, making the area suitable for the growing of horticultural crops like tomatoes, garden eggs, pepper,

onions, watermelons, okra and other leafy vegetables under irrigation (MOFA, 2008).

The region though can boast of two major irrigation projects -Tono and Vea- for all year round farming, majority of the

farmers in the region use dug-out dams, rivers, streams, and with few using hand-dug wells to support dry season

farming. The dry season farming is therefore concentrated mostly in communities near these water bodies, where

crops and vegetables are cultivated along their banks (ACDEP, 2010).

The cultivation of these crops and vegetables is also accompanied by the application of agrochemicals. Farmers

are increasingly relying on inorganic agriculture mainly because, the soils are poor, and indigenous crop varieties

have almost been replaced by improved high yielding varieties which are heavy nutrient miners. Most of the crops

cultivated are short duration crops, among which are vegetables that are most frequently grown in season when

farming is limited to few areas surrounding water bodies. The crops are also quite susceptible to many insect

species, which may not only feed but also reproduce on them. So the farmer seems to have no choice but to treat

crops and protect them against insect species and diseases using agrochemicals. Agrochemicals are crop

protection products or agents used to control plants or weeds, diseases, insects or animals that are undesirable or

harmful to man, and/or also to promote the growth and development of crops. The commonly used agrochemicals

in Ghana are insecticides, herbicides, fungicides, fumigants, fertilizers and growth regulators (Ntow, 2004; PAR,

2000).

Most agrochemicals are toxic and can pose danger to human health (WHO, 2008); hence, their use is highly

regulated internationally, nationally and regionally, with regulations and conventions (PAR, 2000; FAO/WHO, 2001).

As a result of dangers associated with agrochemicals, consumers of agricultural products, especially in Europe and

the Americas are advocating for chemical-free food products for guaranteed health and long lives. Organic

agriculture is thus of late gaining much popularity.

2

It is threatening however that, agrochemicals such as Atrazine, Aldrin, DDT, Paraquat, Alachlor, among others that

have been banned for decades in the European Union (EU) and United States of America (USA) are still used

extensively in many developing countries (Machipisa, 1996; IUPAC, 2008) by local farmers to control pests and

diseases of field crops and food products. These local farmers also have little or no knowledge on how, what, when

and how often to apply agrochemicals on their crops; the consequence of which is the destruction of entire crops

fields, polluting water bodies and putting human health and environment at risk (Ntow, 2004).

Incidentally, many farmers who use these agrochemicals do not know much about the dangers associated with

them and hence end up tasting to determine their potency and also failing to protect themselves during their

formulation and application. Though some stored farm produce are treated with few agrochemicals, most of them

are frequently applied on field crops especially in the dry season along the banks of water bodies such as dams and

rivers, which subsequently ends up polluting and aiding their drying up.

As a result of continuous application of agrochemicals, the fertility status of farm lands is getting worse year after

year; many insects and their predators are destroyed, and others have evolved resistant strains (Tanzubil, 1997).

It is also worth noting that, despite the incessant use of agrochemical products by farmers, 20-40% of potential food

production is still lost every year to pests and diseases (Obeng-Ofori, 1998). Therefore, an adequate reliable food

supply cannot be guaranteed with the use of agrochemical products alone.

Many farmers in Ghana and in many other developing countries are of late relying heavily on agrochemicals in their

quest to produce food crops and vegetables, especially during the dry season (Amoah, et al., 2005; Ntow, 2004;

PAR, 2000). It is against this background that a study was conducted in the Upper East Region of Ghana to

determine the extent and purpose for which farmers use agrochemicals on their crops and other food products, with

a view to suggesting possible interventions to minimizing over-dependence on agrochemicals.

Methodology

This study was recently conducted through farmer group discussions, markets and agro-input shops surveys, and

farmer interviews.

Farmer group discussions were conducted in selected communities of Bawku Municipality, Garu-Tempane,

Kasena-Nankana and Talansi-Nabdam Districts of the Upper East Region of Ghana. This was to obtain general

information on where farmers acquire agrochemicals and on which season agrochemicals are mostly applied on

their crops. Many of the groups members mentioned markets and agro-input shops as places they mostly buy their

agrochemicals; and, dry season as the most predominant season for agrochemical application.

Ten markets and four agro-input shops were then selected at random from among the four districts and visited, to

identify the various types of agrochemicals they deal in and to also find out dealers levels of knowledge on the

usage, formulation, and application of those agrochemical products. Eight dry season farming communities were

then randomly selected from the districts. In each of the eight selected communities, ten dry season farmers were

selected at random amongst lists of dry season farmers and interviewed face to face using a structured

questionnaire. Eighty dry season farmers were interviewed in all four selected districts.

The interview was mainly focused on types of agrochemicals they buy, where they buy them, level of protection,

and on crops those agrochemicals were often applied. Some of the interviewed farmers were also visited in their

farms or gardens to observe where they were and to find out what, how and when agrochemicals are applied on

those crop fields. In almost all cases, farmers dry season crops and vegetables were found growing proximity to

water bodies like rivers, dug-out dams and hand-dug wells. Data collected from the survey was analyzed in SPSS.

Results

The Market Survey

In the market survey, various kinds of agrochemical products including herbicides, insecticides, fungicides,

fumigants, fertilizers and plant growth regulators or hormones were found with agrochemical dealers. There were

also many improved but determinate vegetable seeds found with both market and agro-input dealers.

Some of the agrochemicals found with market dealers had their labels scraped off; others were expired and/or

banned, whilst others were transferred into different containers. Those that had their labels scraped off or

transferred into different containers were difficult to identify. The agrochemical products found with dealers and

identified are shown in Table 1.

3

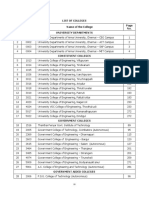

Table 1: Agrochemical Products Found with Market and Agro-input Dealers

Herbicides/Weedicides

Insecticides/Pesticides

Fungicides

Fumigants

Hormones/

Growth

Regulators

Non-Selective

Roundup (Glyphosate)

Gramoxone

Sarosate(Glyphosate/Isopropylamine)

Kalach (Glyphosate acid)

Raundo(Glyphosate/Isopropylamine)

Paraquat*

Alachlor*

Atrazine*

Gramoquat

Glyfos (Glyphosate/Isopropylamine)

Glyphader 75 (Glyphosate acid)

Selective

Calliherbe (Amin salt)

Chemostom (Pendimenthalin)

Anna (Amin salt)

Amino 72 (Dimethylamine salt)

Stam F-34 (Propanil)

Condax-5 (Bensulfuran-methyl)

Deltamethrin

Furadan (Carbofuran)*

Karate (Lambda Cyhalothrin)

Kombat (Lambda Cyhalothrin)

Wreko(Lamda Cyhalothrin)

Kilsect (Lamda Cyhalothrin)

Sumitox (Sulphanate/Ethelene)

Mektin (Abamectin)

Polytrine (Cypermethrin)

Dimex (Dimethoate)

DDT*

Chlorpyrifos (Dursban/Reldan)

Lindane (Gamalin 20)*

Propoxur*

Aldrin*

Bioresmethrin (Pyrethroid)

Actellic (Pyrimiphos-methyl)

Super Guard (Dust)

Dieldrin*

HCB*

Master Insect (Lambda

Cyhalon)

Diazol (Organo-phosphorus)

Conti-Halothrin (Cyhalothrin)

Captan (Captafol)*

Formaldehyde

Topsin-M

(MethylThiophanate)

Funguran-othops

Kocide (Cupper

Sulphate)

Conti-zeb/Manco-zeb

Foko (Manco-zeb)

Champion

Nodox Super 75

Ridomilphi

Pellets

Gastoxin

Phostoxin

Protex

Gastox

(Aluminium

phosphate)

Dust/powder

Baby Nayoka

Wander 77

Commando

Indiana Medi

Liquids

Sidalco

Golden Harvest

Harvest More

Phostrogen

Super Grow

Mono

Ammonium

phosphate

(MAP)

Fertilizers

N:P:K

Sulphate of

Ammonia (SA)

Urea

Surfactant

Bionet

* Banned Chemicals (Source: Amoah et al., 2005; Carl, 1991; Machipisa, 1996; Ntow, 2004)

Most of the farmers buy their agrochemicals and vegetable seeds from the market (Fig 1). These farmers are however rarely given advice or

instructions by the dealers on how to handle and use the agrochemicals when buying them because, most of the market dealers know little, or

nothing about the agrochemical products they sell to farmers.

The Farm survey

It was observed in the farm survey that the problem associated with agrochemical application was further compounded by the fact that farmers who

mostly buy these agrochemicals know virtually nothing on the possible dangers associated with their use. This is probably due to the fact that most

(74%) of the farmers cannot read or write (Fig 2).

4

Fig 1: Sources Farmers Buy their Seeds and Agrochemicals

Fig 2: Literacy Levels of Interviewed Farmers

As a result, how to take precautionary measures during formulation and application of these chemicals are not

known (Fig 3). Therefore, apart from the possibility of using an expired product, most of them may not formulate the

agrochemicals well before applying them and may therefore not achieve the desired results from their application.

Farmers mainly use the agrochemical products on vegetables like watermelon, tomatoes, onions, garden eggs,

aubergines, okra, cabbage, lettuce, and other leafy vegetables. Only few non-vegetable crops like cotton, tobacco,

soybean, cowpea, are also applied with agrochemicals (Fig 4).

The aim of farmers for applying agrochemicals on their crops is either to enhance growth or control pests and

diseases that threaten the survival and yield potential of their crops (Hill and Waller, 1982). Various pests and

disease symptoms were mentioned by the farmers and identified with them on their crops. Identified pests and

diseases farmers believe may cause or are causing damage to their crops which warrant their control with

heavy doses of agrochemicals are shown in Table 2.

N = 80

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

O

w

n

F

r

i

e

n

d

M

a

r

k

e

t

A

g

r

o

-

i

n

p

u

t

s

h

o

p

C

o

m

m

u

n

i

t

y

d

e

a

l

e

r

M

o

r

e

t

h

a

n

o

n

e

s

o

u

r

c

e

N

o

n

e

o

f

t

h

e

m

Sources

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

a

g

e

o

f

f

a

r

m

e

r

s

Seeds

Chemicals

N = 80

74%

19%

7%

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Can only read Can read and

write

Cannot read and

write

Literacy level

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

a

g

e

o

f

f

a

r

m

e

r

s

5

Fig 3: Level of Protection during Chemical Formulation and Application

Fig 4: Crops on which Farmers Apply Agrochemicals

Table 2: Percentage Response of Farmers on most Important Pests and Diseases they Apply Agrochemicals to

Control during Vegetative, Flowering and Fruiting Stages of their Vegetables

Name of

Insect Pest

Vegetative

(%)

Flowering

(%)

Fruiting

(%)

Name of

Disease

Symptom

Vegetative

(%)

Flowering

(%)

Fruiting

(%)

Caterpillars

Mealy bugs

Grasshoppers

Leaf miners

Bees

Butterfly

Fruit fly

Whitefly

Soil pests

No pests

Total

14

3

54

18

0

4

0

2

5

0

100

4

1

15

2

28

2

2

42

2

2

100

5

22

3

1

18

6

12

5

3

25

100

Leaf curl

Leaf spot

Dumping off

Flower/

Fruit drop

Fruit rot

No diseases

Total

48

14

20

2

1

15

100

7

11

2

18

2

60

100

1

1

0

10

23

65

100

N = 80

2%

8%

4% 4%

8%

74%

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

None Only

hands

Only

face

Hands

and face

Whole

body

No

answer

Level of protection

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

a

g

e

o

f

f

a

r

m

e

r

s

N = 80

3%

12%

85%

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Vegetables Others None

Crops

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

a

g

e

o

f

f

a

r

m

e

r

s

6

In most cases, farmers target more than one insect pest or disease symptom during chemical application. Some

farmers believe that any insect, including bees found on crop field at flowering and fruiting stages are causing or

likely to cause flower and/or fruit abortion and are equally targeted with pesticides. It is not only field crops pests,

but stored produce pests are also treated with agrochemicals.

In other to control insect pests and diseases of most importance to the farmer, several applications of

agrochemicals are made on crops and vegetables like watermelon, tomatoes, and onions before harvest (Table 3).

The multiple applications is partly due to the low chemical concentrations rate, adulteration, misapplication,

ineffective and/or expired chemicals farmers use in some cases, as observed during the survey.

It is however quite threatening to apply agrochemicals for such a number of times before harvesting, not forgetting

of the fact that some of these vegetables are mostly eaten raw or slightly cooked (Ntow, 2004; Amoah, et al., 2005).

Even more threatening is that, farmers can harvest their produce for sale few days after last chemical application

(Fig 5), even though some of the chemical products used by these farmers have residues which can be retained on

crops and vegetables for extended periods (Kleter, et al., 2008). Research also has it that, there is gradual

cumulative evidence of increasing human vulnerability to agrochemicals and chemically applied food products

(Amoah et al., 2005; Ntow, 2004; Smith, et al., 1999).

Table 3: Percentage Response of Farmers on the Number of Times they Apply Chemicals on Tomatoes,

Watermelon, and Onions before Harvest

Number of times Tomatoes

(%)

Watermelon

(%)

Onions

(%)

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13-15

Total

19

2

8

44

12

7

1

0

0

3

2

0

0

2

100

1

3

3

11

8

2

7

23

8

1

16

2

7

8

100

21

4

7

48

5

10

3

2

0

0

0

0

0

0

100

Fig 5: Periods Farmers Start Harvesting their Vegetables after Last Chemical Application

N = 80

14%

17%

46%

23%

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

1 2 3 4

Number of weeks

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

a

g

e

o

f

f

a

r

m

e

r

s

7

Whilst some farmers have reasons necessitating such numerous chemical applications, majority (54%) of them do

not know why they keep applying agrochemicals (Fig 6). To them, treating the crop continuously with agrochemicals

is a common practice to maximize yield and attract good market prices; because both leaves and fruits will be free

of insect and disease infestation and will be more appealing and attractive to the consumer.

Fig 6: Farmers Reasons for Continuous Application of Agrochemicals

Farmers also know little about other alternatives to synthetic chemicals (Fig 7), as synthetic chemicals are known

and/or thought to be the most potent, rapid and reliable means of reducing pest and disease incidence on food

crops. As a result, those who know other alternatives to synthetic chemicals are either not interested in such

alternatives or do not appreciate their benefits or importance.

Unlike synthetic chemicals, botanicals are often not available in the market; hence, farmers are over relying and

depending on synthetic chemical products to produce food crops and vegetables for consumption and for income.

Fig 7: Farmers Awareness of other Alternatives to Inorganic Chemicals

N = 80

54%

3%

6%

15%

3%

19%

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

N

o

t

p

o

t

e

n

t

e

n

o

u

g

h

N

o

t

w

e

l

l

f

o

r

m

u

l

a

t

e

d

/

s

p

r

a

y

e

d

I

n

s

e

c

t

s

n

o

t

d

y

i

n

g

I

n

s

e

c

t

s

f

l

y

a

w

a

y

a

n

d

r

e

t

u

r

n

D

i

f

f

e

r

e

n

t

i

n

s

e

c

t

s

c

a

m

e

N

o

r

e

a

s

o

n

Reasons

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

a

g

e

o

f

f

a

r

m

e

r

s

N = 80

3%

8%

89%

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Plant extracts Synthetic

chemicals

No answer

Awareness

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

a

g

e

o

f

f

a

r

m

e

r

s

8

Discussion

Unlike in the past, traditional options have been reduced or eliminated, resources are lacking, soils are poor, and

illiterate farmers predominate in farming communities in developing countries such as Ghana. These farmers have

little or no knowledge on how to improve the soil or reduce pest and disease infestations without using

agrochemicals, and may not even know there are dangers associated with agrochemicals. Though there may be

existing evidence of associated dangers of agrochemical misuse, such evidence is hardly believed to be associated

with agrochemicals, because their effects are gradual and seldom noticed. As a result, farmers rarely take caution

during handling, formulation and application of these agrochemicals, and these acts put the farmers and the

consumers health at risk (Smith, et al., 1999).

The numerous and continuous application of agrochemicals by farmers on crops before harvest (Table 3) even if

some reasons (Fig 6) necessitate such applications, may not be of any benefit to the farmer. Apart from investing

much labor and other resources, agrochemicals are expensive and are also beyond the reach of most farmers. In

addition to this, the yields from crops grown on farmers soils year after year seldom make inorganic chemical

application economically viable (Reinders, 2007).

The continuous use of agrochemicals may also seem to be controlling pests and diseases and probably increasing

crop yields each year, but in reality, yields are decreasing. The economic returns or the net income accruable to the

farmer, based on the gross income and expenditure on agrochemicals alone may not be anything to write home

about. However, farmers cannot quantify this and take caution on the number of agrochemical applications they

have to make before harvesting their farm produce. Although farmers seems not to be interested or do not

appreciate the benefits of other alternatives to inorganic chemicals, other alternatives should be considered, since

inorganic chemical use under this prevailing farming system is not an attractive option.

In the Upper East Region of Ghana, as well as in other regions of the Country, agrochemical usage should be a

focus for developing agricultural extension policies that seek to help farmers avoid, minimize, or adapt chemical-

free farming practices for the benefit of every one. There is no regulatory measure that could fully achieve its

intended purpose without active participation and support of all stakeholders. Developing countries such as Ghana,

should involve stakeholders in implementing measures to reduce risk associated with agrochemical application.

Apart from farmers, communities must also be prepared to accept a change and assist in minimizing agrochemical

misuse. To prevent or reduce harmful effect of agrochemicals, farmers must be ready to learn and practice good

farm management.

To achieve this, adequate support and effective extension services must be put in place. Farmers should also be

well organized for effective farmer participatory learning practices. The gradual cumulative evidence of increasing

human vulnerability to agrochemicals and chemically applied food products (Amoah et al., 2005; Ntow, 2004; Smith,

et al., 1999) should also call for significant policy response and action on several fronts in developing countries.

Prior action to mitigate associated problems with continuous use of agrochemicals and to also boost farmers

capacity to cope with or prepare for change from chemical to chemical-free farming practices makes more sense as

a long term measure.

Safety considerations pertaining directly to the use of agrochemicals should include education and training

programs that relay how chemical products can be used safely and efficiently, whilst avoiding expired or banned

chemical products. It is again critical for farmers to be educated on ways to avoid some of the inherent risks of

sometimes harmful or toxic chemicals they often handle. They should also show keen interest in learning about

agrochemical products, their effects and how to effectively formulate and apply them to increase productivity without

much health implications. End-users (consumers) of agricultural produce should learn about the dangers of

agrochemical misuse and also take keen interest to know much about what they eat (Groth, et al., 2000).

Possibility of change in the near future may need short-term prevention and management measures to reduce

farmers use of agrochemicals to the lowest level possible (Adger, et al., 2001). So there is the need for a concept

of integrated approach to areas of safe and responsible use of inorganic and organic chemicals, as an integrated

pest management strategy to reduce if not entirely, the risk associated with sole reliance on inorganic chemicals.

This could be done in a gradual process through farmer participatory approaches aimed at introducing to farmers

the possible alternatives to inorganic chemicals. It should be a gradual process because too fast a rate of change

may exceed the capacity of the farmer to adopt. It will also help facilitate effective intervention strategies to

improving farmers knowledge base on dangers associated with agrochemicals and possible alternatives to

inorganic chemicals.

Every human generation therefore has an obligation to preserve the natural and agricultural heritage for its

successors, so that todays production does not reduce or hinder the capacity of the future generation to produce

what is necessary for life (FAO, 2002). So, while hungry mouths may depend on any means possible, detrimental or

not, to obtain food and income for sustenance of their livelihood, natural resources must be protected and

preserved for posterity through some of the following measures:

9

Stakeholder training program involving farmers and agrochemical dealers on acceptable agrochemicals and

their formulations and usage should be organized regularly by relevant government agencies;

Farmers should be educated to desist from growing food crops along the banks of water bodies and applying

agrochemicals on them;

Farmers should be educated on dangers of agrochemicals and encouraged to desist from harvesting,

consuming or selling farm produce that have been applied with agrochemicals less than a month old.

Depending on the extent of pest and disease infestation on a crop, agrochemicals should not be applied

beyond 1-3 times on an infested crop.

Farmers should be educated on timely planting of resistant but vigorous varieties to help minimize pest and

disease incidence on crops;

The use of soil friendly practices such as composting and leguminous cover cropping should be encouraged,

instead of herbicides to prevent growth of unwanted plants (weeds) in crop fields; and

Different plant products (leaves, seeds, oils and ash) can be used to protect crops and foodstuffs against insect

pest damage. So in an attempt to control pests, farmers could use botanicals such as neem (Azadirachta

indica, Juss) extracts, since it is very effective against several insects and mite species (Obeng-Ofori, 1998;

Tanzubil, 1997).

Conclusion

The extent of use, level of education and protection, and reasons of farmers for relying heavily on agrochemicals to

protect crops and vegetables which could be eaten raw or slightly cooked, presupposes that the farmer as well as

the consumer is likely to be exposed to various forms of agrochemical substances. The continuous application of

agrochemicals pollutes water bodies thereby posing health hazards to humans, animals, and wildlife. The insects

could also gradually evolve resistant strains to pesticides and in the long run become pests to man. Reduction in

the impact of agrochemical dangers will therefore depend mostly on skills, information, and education.

The focus should therefore be an increase investment and awareness creation through sound extension services

on management of farm environment and reduction in agrochemical use by farmers. Priorities in developing

countries like Ghana should therefore go to policies that will reduce the vulnerability of the poor farmer to dangers

of agrochemicals, as part of general strategies towards poverty reduction, food security, and sustainable agriculture

development.

This can be made possible through education and farmer participatory practices, and gradually integrating inorganic

and organic agriculture towards reducing farmers over reliance on agrochemicals. Though reduction in the use of

agrochemicals can have biodiversity benefit, for sustainable and stable crop production, organic agriculture is more

appropriate. Apart from producing chemical-free foods in the long run, the environment and its natural resources as

well as farmers and consumers could be saved or protected for posterity.

Acknowledgements

I thank Mr. Solomon Atigah and Madam Liticia Sampoa Apam of Presbyterian Agriculture Station (PAS), Garu, and

Mr. Jonathan Agawini of Savanna Agricultural Research Institute (SARI) for assisting me in various ways during my

preliminary surveys. I am also grateful to Prof. K. Ofori of University of Ghana, Prof. B. Tanzubil of Bolgatanga

Polytechnic, and Dr. W. Dogbe of SARI for their contributions and also reading through the manuscript.

References

Amoah, P., Drechsel, P., Abaidoo , R. C. & Ntow, W. J. (2005). Pesticides and Pathogens Contaminations of

Vegetables in Ghanas Urban Markets. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 50(1):1-6.

Adger, N., Kelly, M. & Bentham, G. (2001). New Indicators of Vulnerability and Adaptive Capacity. Paper

Presented at the International Workshop on Vulnerability and Global Environmental Change: Lila Nyagatan,

Stockholm. 17-19

th

May, 2001.

Association of Church Development Projects (ACDEP) (2010). Acdep-Networking for Development in Northern

Ghana: The Upper East Region. htt://acdep.org/wordpress/acdep-operational-region/the-upper-east.

Carl, S. (1991). Exporting Banned and Hazardous Pesticides, 1991 Statistics. Second Export Survey by the

Foundation for Advancements in Science and Education (FASE) Pesticide Project.

Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) (2002). Crops and Drops : Making the Best Use of Water for Agriculture.

Rome. World Food Day, 16

th

October, 2002. 28Pp. www.fao.org/landandwater.

10

Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) / World Health Organization (WHO) (2001). Amount of Poor-quality

Pesticides Sold in Developing Countries Alarmingly High. Press Release, 1

st

February, 2001. Rome.

Groth, E., Benbrook, C. M. & Lutz. (2000). Update: Pesticides in Childrens Foods, an Analysis of 1998 USDA, PDP

Data on Pest Residues. Consumers Union, May, 2000.

Hill, D. S. & Waller. J. M. (1982). Pests and Diseases of Tropical Crops. Vol. 1. Principles and Methods of Control.

Longman. London. Pp 175.

International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) (2008). Global Availability of Information on

Agrochemicals. 12

th

IUPAC International Congress on Pesticides Chemistry, 15

th

July, 2008.

http://agrochemicals.iupac.org/.

Kleter, G. A., Harris, C., Stephenson, G. & Unsworth, J. (2008). Comparison of Herbicide Regimes and the

Associated Potential Environmental Effects of Glyphosate-resistant Crops Versus What They Replace in

Europe. Journal of Pest Management Science. 64(4): 479-488.

Machipisa, L. (1996). Banned Pesticides Heavily Used in the Third World countries. Albion monitor, November 23,

1996. http://www.monitor.net/monitor.

Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MOFA) (2008). Agriculture in Upper East Region.

http://www.mofa.gov.gh/UER-RADU.html.

Ntow, W. J. (2004). Organochlorine Pesticides in Water, Sediments, Crops and Human Fluids in a Farming

Community in Ghana. Journal of Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 40(4): 557-563.

Pan African Regulation (PAR) (2000). Pan Africa Regulation of Dangerous Pesticides in Ghana. Pan African

Monitoring and Briefing Series No. 5, Dakar, Senegal, 16Pp.

Obeng-Ofori, D. (1998). Post Harvest Science. Crop Science Department. University of Ghana, Legon,

October, 1998. 71 Pp.

Reinders, H. P. (2007). Learning Together for Organic Farming. In: Low External Input and Sustainable Agriculture

(LEISA), Magazine, March, 2007 edition 23(1): 15-17.

Tanzubil, P. B. (1997). None-pesticidal Approaches to Managing Insect Pests of Sorghum in Ghana. In:

Proceedings of the Third National Workshop on Improving Farming Systems in the Interior Savanna of Ghana.

Nyankpala, Tamale, Ghana. April, 1993. Pp 227-236.

Smith, K. R., Corvalan, C.F. & Kiellstrom, T. (1999). How Much Global Ill Health is Attributed to Environmental

Factors? Journal of Epidemiology 10(5): 573-84.

World Health Organization (WHO) (2008). Public Health and Environment and Quantifying Environmental Health

Impact. (www.Who.int/topical environmentalhealth/en/.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Health and Hatha Yoga by Swami Sivananda CompressDocumento356 pagineHealth and Hatha Yoga by Swami Sivananda CompressLama Fera with Yachna JainNessuna valutazione finora

- AITAS 8th Doctor SourcebookDocumento192 pagineAITAS 8th Doctor SourcebookClaudio Caceres100% (13)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Meditation For AddictionDocumento2 pagineMeditation For AddictionharryNessuna valutazione finora

- Contract of Lease (711) - AguilarDocumento7 pagineContract of Lease (711) - AguilarCoy Resurreccion Camarse100% (2)

- (IME) (Starfinder) (Acc) Wildstorm IndustriesDocumento51 pagine(IME) (Starfinder) (Acc) Wildstorm IndustriesFilipe Galiza79% (14)

- Lesson 17 Be MoneySmart Module 1 Student WorkbookDocumento14 pagineLesson 17 Be MoneySmart Module 1 Student WorkbookAry “Icky”100% (1)

- Chapter 16 - Test Bank Chem 200Documento110 pagineChapter 16 - Test Bank Chem 200Jan Chester Chan80% (5)

- 19-Microendoscopic Lumbar DiscectomyDocumento8 pagine19-Microendoscopic Lumbar DiscectomyNewton IssacNessuna valutazione finora

- 5g-core-guide-building-a-new-world Переход от лте к 5г английскийDocumento13 pagine5g-core-guide-building-a-new-world Переход от лте к 5г английскийmashaNessuna valutazione finora

- SRL CompressorsDocumento20 pagineSRL Compressorssthe03Nessuna valutazione finora

- Dumont's Theory of Caste.Documento4 pagineDumont's Theory of Caste.Vikram Viner50% (2)

- Tugas SPAM FHM FJPDocumento2 pagineTugas SPAM FHM FJPM RiendRa Rahmatullah UslaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Tugas FDocumento2 pagineTugas FM RiendRa Rahmatullah UslaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Tugas H PDFDocumento2 pagineTugas H PDFM RiendRa Rahmatullah UslaniNessuna valutazione finora

- E Jam Standmeter Debit Standmeter Debit Standmeter Debit Rata2 PatternDocumento2 pagineE Jam Standmeter Debit Standmeter Debit Standmeter Debit Rata2 PatternM RiendRa Rahmatullah UslaniNessuna valutazione finora

- D Jam Standmeter Debit Standmeter Debit Standmeter Debit Rata2 PatternDocumento2 pagineD Jam Standmeter Debit Standmeter Debit Standmeter Debit Rata2 PatternM RiendRa Rahmatullah UslaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Tugas C PDFDocumento2 pagineTugas C PDFM RiendRa Rahmatullah UslaniNessuna valutazione finora

- TNEA Participating College - Cut Out 2017Documento18 pagineTNEA Participating College - Cut Out 2017Ajith KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Duterte Vs SandiganbayanDocumento17 pagineDuterte Vs SandiganbayanAnonymous KvztB3Nessuna valutazione finora

- PUERPERAL SEPSIS CoverDocumento9 paginePUERPERAL SEPSIS CoverKerpersky LogNessuna valutazione finora

- Book Review On PandeymoniumDocumento2 pagineBook Review On PandeymoniumJanhavi ThakkerNessuna valutazione finora

- Ob AssignmntDocumento4 pagineOb AssignmntOwais AliNessuna valutazione finora

- Https Emedicine - Medscape.com Article 1831191-PrintDocumento59 pagineHttps Emedicine - Medscape.com Article 1831191-PrintNoviatiPrayangsariNessuna valutazione finora

- Oral Oncology: Jingyi Liu, Yixiang DuanDocumento9 pagineOral Oncology: Jingyi Liu, Yixiang DuanSabiran GibranNessuna valutazione finora

- 1-Gaikindo Category Data Jandec2020Documento2 pagine1-Gaikindo Category Data Jandec2020Tanjung YanugrohoNessuna valutazione finora

- Novedades Jaltest CV en 887Documento14 pagineNovedades Jaltest CV en 887Bruce LyndeNessuna valutazione finora

- Holophane Denver Elite Bollard - Spec Sheet - AUG2022Documento3 pagineHolophane Denver Elite Bollard - Spec Sheet - AUG2022anamarieNessuna valutazione finora

- Anxxx PDFDocumento13 pagineAnxxx PDFDamion HaleNessuna valutazione finora

- Mendoza - Kyle Andre - BSEE-1A (STS ACTIVITY 5)Documento1 paginaMendoza - Kyle Andre - BSEE-1A (STS ACTIVITY 5)Kyle Andre MendozaNessuna valutazione finora

- Improving Downstream Processes To Recover Tartaric AcidDocumento10 pagineImproving Downstream Processes To Recover Tartaric AcidFabio CastellanosNessuna valutazione finora

- LEWANDOWSKI-olso 8.11.2015 OfficialDocumento24 pagineLEWANDOWSKI-olso 8.11.2015 Officialmorpheus23Nessuna valutazione finora

- Iluminadores y DipolosDocumento9 pagineIluminadores y DipolosRamonNessuna valutazione finora

- English 10-Dll-Week 3Documento5 pagineEnglish 10-Dll-Week 3Alyssa Grace Dela TorreNessuna valutazione finora

- Digestive System LabsheetDocumento4 pagineDigestive System LabsheetKATHLEEN MAE HERMONessuna valutazione finora

- Peter Honigh Indian Wine BookDocumento14 paginePeter Honigh Indian Wine BookVinay JohnNessuna valutazione finora

- Ra 7877Documento16 pagineRa 7877Anonymous FExJPnCNessuna valutazione finora