Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Part 3

Caricato da

api-235360943Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Part 3

Caricato da

api-235360943Copyright:

Formati disponibili

In this section, I will be considering different variables with group sizes and how

they relate with conflicts. More specifically, I will look through the lens of students and

how they faced conflict within different sized groups: four, three, and partnerships. Id

admit, this wasnt originally what I had set out to do all started when began the research

process. It happened when I was interviewing students for my focus group. I had all my

questions thoughtfully planned out to ask my focus students. What happens when you

are in a conflict? Tell me about when you and a friend disagreed on something. It was a

great conversation, but I had already been down the conflict road. Just to have some sort

of closure to the conversation, I just asked the students: Anything else youd want to

add...Do you even like working in groups?

Keith: Depends on the size.

Me: All right, so then whats your ideal group number?

Zane: Three is always good because they can talk to others if there is a problem

Me: You dont like four?

ALL: NO! (In unison)

Keith: To me four is really hard. There are always one or two people doing the

work and the other students slacking off.

Mary: Depends on what the project is. Like, if its a longer project, sometimes

more people work.

Keith: There are too many names to write in on the line

Zane: Four is a bit too much. Five is unheard of.

Me: This is has been really enlightening.

It truly was.

I had focused the majority of my exploration on student conflict; hitherto I

neglected to think about the variables in grouping strategies and the imperative role they

played. In project-based learning, the students need to communicate often outweighs the

outcomes of the learning objectives. While endeavoring to make the lines flow more

freely in my classroom, I was struck by the different variables when forming groups and

how this affects communication habits among seventh graders.

The different variables I explore in this chapter are: the number of students in a

group; student choice in grouping versus teacher assigned groups; and importance of

assignments.

I intend to look at this through two different lenses: the teacher perspective and views of

a student, Alyssa.

Case study: Alyssa

Alyssa is a diligent seventh grade student. She had a 504 disability plan for

organization, visual processing and borderline dyslexia. Yet, in spite of the obstacles she

faced in my humanities class, she was an extremely hard worker.

She has a core group of friends. Through my observations, I have noticed she opts

to work more with male students rather than female. For example, when asked to choose

her partners for our Dystopia project, she chose two boys.

On the surface Alyssa appears flexible and easy-going, yet when she is frustrated

she does speak up to her group members or advocate that to the teacher. A clear example

of this occurred while students were in their literature circle groups, they appeared to be

laughing, especially Alyssa. However, later, reading her reflection journal, she wrote:

my group got off task, it was kind of annoying.

She never vocalized that point to her group member. It is my understanding that

in certain group situations, Alyssa desired to please her peers and does not want to get off

task.

Part one: Groups of Four

In my classroom, I most frequently grouped students in fours. The assignments

varied. Ive used groups of four long term projects, short one-class activities, or table

discussions. Ive been accustomed to grouping students based on a number of criteria

dependent on what I would like the students to produce. My thinking surrounding groups

of four was purely task-driven. As a general rule, Ive tried to make the groups fit so they

would work well together and get the task done. I justified that there was some magic

recipe to mix up the perfect group. There was little data to support how successful groups

were based on my grouping methods. Generally, I chose the ingredients:

I ngredient 1:

o Gender. I would always mix two boys and two girls. Sometimes I would

have a group of all girls and sometimes all boys.

o I would never put three boys and one girl and vice versa.

I ngredient 2:

o Personalities. I would mix some quieter students with some more

outgoing.

I ngredient 3:

o Academic Ability.

o I grouped students according to academic ability. Often times, I would

mix two high-achieving students with one or two lower achieving

students. It was challenging at times with that mix because the higher

achieving students were more motivated and the responsibilities and stress

would fall on them.

I ngredient 4: Student interest. If there was a student who was a strong writer,

they would be the editor. If a student was a master carpenter, they became the

builder, and so on.

Frequently this rationale for how I grouped students was successful. Students

were, for the most part, able to complete the work and generally got along. Cohen in her

book, Groupthink believes groups larger than five present problems for participation.

For group discussion, I have always found that four or five is an optimal size (Cohen,

1994, 73). In my classroom, however, I disagree with this statement. Students in groups

larger than four have difficulty discussing topics. I have witnessed year after year when I

conduct literature circles, I have struggled with students to comprehend the ways of

involving all students in larger groups. An example of this was literature circles that I

have conducted since the first week of school. There were groups of four reading the

same number of pages. While I have done literature circles for a number of years, I have

always struggled with equal student participation. This also rang true for the first

literature circle this year. In order to combat the forced conversations that were occurring,

I created a step-by-step process for communicating each students thoughts on the weeks

reading.

The overall feedback varied from group to group. When I asked the students

How did the discussion go? 82 percent of students wrote their group wrote, It went

well. The times the conversations did not go well, were when a member of the group

was ill prepared and they didnt read the required amount. This led to, as one student put

it we were all frustrated with [the students name] because we couldnt talk about what

had happened because he didnt read where we were supposed to. Conflicts mostly

emerged because of lack of productivity. When one student did not contribute, the

discussion suffered, and therefore, the students were not able to get a rich discussion from

the protocol. The key was that the students were not ready for a rich discussion. Ensuring

that all students are adequately prepared is a strong point to consider when implementing

groups of four in the classroom. While there are some truths to student participation,

larger groups tend to swallow up quieter students who are unsure of the work or are ill

prepared.

When students are given a structure to communicate in a larger group, they will

cooperate and follow protocol. Unfortunately, when students are unprepared, it creates

conflict for the other members of the group, especially if there are students who are task-

driven sharks. The strongest conversations happened when all of the students were

engaged in the book and when all group members were prepared with all of the materials

to participate in the discussion.

Another time I implemented a group of four was when I had students create their

own government. Unlike the literature circle discussion groups of four, this was a

brainstorming activity and all of the students needed not to prepare for the discussion,

rather I wanted it to occur organically. Furthermore, there was no structure for the

conversations.

Imagine you and the rest of the school were transported to a place with enough

natural resources for you to live well, but where no one had lived before. When

you arrive, you have no means of communicating with people in other of the

world. With this imaginary situation in mind, consider, debate, and answer the

following questions within your group.

Create a visual constitution of your society to share with the rest of the class...

1. Upon arrival, would there be any government or laws to control how you

lived, what rights or freedoms you exercised, or what property you had?

Why?

2. Would anyone have the right to govern you? Would you have the right to

govern anyone else? Why?

3. Would you have any rights? What would they be?

4. What might people who were stronger or smarter than others try to do

Why?

5. What might life be like for everyone?

The students were in a group of four, discussing the answers to these critical

thinking questions. What I uncovered was a polarizing dialogue. When listening in to one

group of students, there were two boys and two girls who each had two divergent ideas

on how to run their land. The two girls in the group would not listen to either of the two

boys at their table. They refused to compromise. In fact, they argued about all of the

questions. It was two-against-two, locked in a stalemate. In this case, they would have

need a fifth party to come in and mediate the compromise. I became that fifth person.

The conflict was unable to be solved because there were equal sides represented.

This could often occur in groups of four because of the nature of even numbers.

Alyssa in a group of four

Alyssa has identified herself as a shark twice and fox once when working with in

a group of four. She often voiced her struggles when she worked with students when they

are not producing. Additionally, she tends to become too social and can get off task when

in a group of students who tend to be more socially focused. This was apparent when she

explained, I dont appreciate when [in my group] people slack off and don't put effort

into things. I believe that while Alyssa desired to get the work done. She showed her

frustration with her group members because she wanted every group member to equally

contribute. However, she did not say anything to her group member, rather she remained

silent.

Groups of four offer certain benefits. It is clear they can help students motivate

one another to work. They can serve as sharing a variety of perspectives on a particular

theme when in a discussion. Furthermore, in more task-demanding projects, groups of

four help support the division of labor for each in order for each member to complete

their portion of the work.

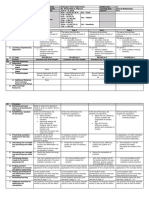

Pros Cons

Strong discussion can

occur, when facilitator

or protocol is present

More student

contribution of ideas

Stronger

communication among

small group

A third party could

settle conflicts. (Group

harmonizer)

Students can gain a mix

of opinions and weigh

evidence from group

members.

Could polarize ideas

Could be difficult to come

to a decision

Division of labor is

problematic.

Groupings based on a

variety of criteria is

challenging

Too many ideas could lead

to conflict

May need an outside

mediator to resolve

conflicts (teacher)

Student voices could be

overshadowed

More voices means more

conflict

Groups of three

From the conversation I had with my student focus group, I decided to group

students in threes for a dystopian video documentary project. The students were to create

a thematic video that incorporated quotes from various dystopian literatures that we were

reading in class. I assigned the roles.

Each group had one editor and two students on filming crew. Students were able

to choose what role they wanted to have. They were required to collectively create a

storyboard, film and act in each scene. Then only one student would focus on the editing.

In the beginning, the students worked rather well creating their storyboard. When they

began filming, there were creative differences; some students had different visions on the

filming and time management.

At the end of the project, students reflected and evaluated each other group

members on their work, productivity, and effort. They filled out a scaled score about each

of their partners, and that would contribute to their final assessment of their grade for the

project. About halfway through the day, I overheard an argument from the students from

one specific group. The project was completed and they had turned in the work.

I followed up with them to find out what had transpired. When the boys assed

each others work during the evaluation processes, one of the students, Joey, marked his

partners much lower. Fearing their grade was going to be lowered, David and Jesus were

upset with Joey. They became aggressive and began to shout at Joey. In this moment, it

made me realize that groups of three, while they can be successful in ensuring

cooperation and participation among all members, can lead to triangulation and unfair

ganging up on a third student. When thinking about utilizing groups of three, another

point to note is that of student peer groups. The three boys in this scenario were from

different social groups. David and Jesus were friends and Joey was not in the same social

group.

It is important to note the role of status that was played in this group dynamic.

Both David and Jesus are considered high peer status students. High status students tend

to have high peer influences or high academics (Cohen, 1994, 22). High status students

have more influence. Through out the project, both boys dominated groups. Additionally,

during the year, I noticed that David and Jesus are group leaders. They tend to take

charge both in the class as well during social situations. I have often witness Jesus

specifically leading basketball games or tag during lunch and break. Conversely, Joey is

to have lower status among his peers. He tends to be on the quieter side and has often

lacked initiative. Lower status students dont talk as much as other students (Cohen,

1994, 36). I had witnessed throughout the project Joeys ideas had been pushed aside. For

instance, before recording a scene for their videos, David and Jesus decided that Joey

would be the cameraperson and the two boys would be the actors. Joey did not protest.

When I asked him about it later he said he didnt mind. It was only when I had read his

evaluation of his partners, he wrote, they bossed me around and didnt let me act.

Alyssa in a group of three

Alyssa worked with two other students on the dystopian video project. She was

able to complete the work because she had a voice on which students could work with,

which is important to her. However, through out the project, Alyssa was often not

focused on managing her time and, by default, ended up socializing with her friends.

While she is hard working, sometimes working with your friend group, can pose a

challenge.

When I had talked to her about the project, her insight was remarkable:

Me: How do you think the project went?

Alyssa: I think it went ok. Sometimes [her partners] would ditch me.

Me: Did you say anything to them?

Alyssa: No. I was trying to get my work done and I needed a quiet space.

Me: Oh. What would you do differently next time, if you had to work with them?

Alyssa: Honestly, I dont think thatd be a good idea.

Me: Oh, why not?

Alyssa: Because we talked too much. I had to leave them alone. They were so

distracting and I didnt want to do a bad job.

This dialogue with Alyssa proved to be thought provoking on a few accounts. One

phrase that stood out to me was when, after her group members ditched her, Alyssa

decided to focus on the work at hand. This shows a true student who cares about the

integrity of her work. She likewise realized the pitfalls of working with students who get

her off task. Although it was difficult for her during the process, I believe that the conflict

with her peers had taught her a valuable lesson. Lastly, sometimes in a group of three, the

odds could be against one person. In the case of Alyssa, she was able to overcome being

convinced to not do work, and was able to forge her own path.

In both student scenarios, the role of status played a significant position. Alyssas

status was much higher than the two other students. She was well liked by her peers and a

high achieving student. Because of this, Alyssa removed herself from her other two peers,

of lower status, and did the remainder of the work on her own. The other students didnt

argue, rather they worked together and helped complete the work

Pros Cons

Democratic votes with odd

numbers (two-against-one)

Work could be divided

evenly

Hold each other more ac-

countable for the workload.

Ease of grouping

academically and by

abilities. e.g. film crew,

editor, and music designer.

Could have a group

harmonizer (third party to

negotiate)

Engage in a two-against-

one argument

Two students could leave out a

third one

Two students could easily gang

up on the third, and could be

unfair

Partnerships

Partner work is great. I use it in my class virtually every day. I can implement

partnerships during pair share, looking at an article, jigsaw, etc. I habitually apply partner

work for smaller activities, and have rarely done larger-scale projects with two students.

What is noteworthy from the data in relation to partnerships, there were a much larger

number of students who identified themselves as compromising foxes. Because of this

larger number it explained that students were better at compromising and solving

conflicts with one other person, rather than a few others.

The chart below shows how the students identified themselves when they worked

in a group of four and when they worked in a twosome. I believe that this is because the

students have only one student to negotiate with and, therefore, forced students to be

more open in compromising. Partnerships offer valuable collaboration, but keep the

stakes high for students who tend to be more social.

Alyssa in a partnership

Throughout the year, Alyssa has proved to do well in partner work. I have

observed that Alyssa has consistently done a wonderful job of stepping up and stepping

back.

On the exit card from the Historys Mysteries partner project, she reflected, this

was a really easy project to finish and learn about the mysteries. In a follow up

interview, I had asked why it was so easy for her. I liked my partner that I worked with

and we both knew what to do. She identified herself as a compromising fox when

working in the pair. She was also paired with a student, Kerri, who had identified herself

as a fox each time she worked in a group. Her feedback from working with Alyssa: I

think that I was a fox because there were times when I had to be a shark so we could

finish our work. Other times, I was an owl when our product or pictures were falling

apart. Because two self-identified foxes worked together, the result was beneficial to

each of the parties. They were able to compromise and work together to complete the

task. Alyssa was able to advocate for herself and the same with her partner. In larger

groups, she tended to get more frustrated with stronger personalities and students who

lacked follow through.

Concluding notions about group variables

When implementing, teachers need to consider objectives of the assignments.

They also need to deliberate what they want the students to learn from the work.

Different grouping sizes can foster better communication. Larger groups should use more

of a structured guide in navigating conflict. However, conflict occurs more frequently

when more voices are involved. This is due to the fact that when students have a larger

number of students in a group, the lines of communication become tangled.

On the other hand, partnerships offer a lower stakes way of students learning

basic negotiation and compromising skills. Either way, grouping has undoubtedly shaped

the nature of communication in my classroom.

Student Autonomy in grouping

Whenever I begin a project, I take the time to go through the deliverables, in other

words, what the students need to create and the timeline in how long the project is going

to last. It warrants a twenty-minute explanation of the project. This is commonly known

as a project launch. Inevitably, the most popular question students ask when Im done

pontificating on how wonderful the project is going to be is do we get to choose our

group? Without fail, Ive always snapped back, No! I never had students solely

choose who they would be paired with because I feared that students would not

accomplish the desired task.

However, I have given students the opportunity to advocate working with one

other person if they gave me a valid enough reason. They are often very specific. One

student wrote Because on our last project [students name] and I were able to manage

our time and we got all of our work done. Others are very humorous I dont want to

work with [students name] because in the Egypt project in sixth grade, they did not let

me do anything and then yelled at me for not doing any work. I try to stay away from

volatile relationships and, up until recently, never really let students work with their

friends. However, when thinking about conflict, I couldnt help but wonder if students

were more or less prone to conflict when working with a friend or a group of friends.

The typical aversion of teachers letting students work with their friends is that

they will spend more time talking than getting their work done. But in terms of creating a

classroom that fosters open communication, I took the risk and let them choose. I have

never let students in middle school choose whom they are working with. The experts

agree with me. Cohens (1994) book Groupwork she wrote: Students should think of

group work in terms of work rather than play, and there is clearly a tendency for the

friends to play rather than work, when assigned to the same group. Furthermore, some

students who are social isolates will not be selected or will actively be rejected for group

memberships. Against my better judgment, and the experts, I faced my trepidation and

wanted to see what would transpire if the students were allowed to work with their

friends.

I started small.

I had the students read and annotate a short story. It was a quick and

straightforward assignment. I gave them the option of choosing one person, two people or

to work alone (mindful of Cohens thoughts about students feeling rejected). Fig. 1 shows

the completion all three parts of the assignment of assignment in three parts:

(1) They needed to read Kurt Vonneguts, short story 2Br02B,

(2) Annotate the text.

(3) Find a quote that stuck out to them and connect that particular quote.

They were given two hours to complete all three tasks. Class A was permitted to choose

their groups or work alone. Class B, I chose the student grouping and they werent given

the option to work alone.

Additionally, I chose the groups based on academic readiness and work ethic.

(These are traditionally how I would group students)

Allowing students to choose their groups finds teachers in precarious territory.

According to the data, I found it was not as I had risky as I had previously anticipated.

My original thought was that students would be counter-productive and completely miss

the learning objectives of the assignment, and thus, wasting class time. However, looking

at the data, I discovered a few surprises.

When students worked with their friends, they offered both support and

hindrances. In terms of support, students were more apt to bring up important issues with

their friends because they feel more comfortable addressing it, as the charts depict below.

I wanted to look at in what way they interacted with their peer groups rather than

teacher assigned groups. Students often spend more time getting off task than completing

an assignment. Some of their responses were:

Because I got along with my partner

Because we know when to stop [and get refocused]

I work harder with my friends

There were several revelations that I found when students worked in groups of

their choice. While I had previously, and wrongfully, assumed they would not get the

work accomplished that was on the instance in a few groups. More important to note was

that when students worked with their friends, they were more apt to advocate their needs.

When students choose the groups, there are a few positive they tend to advocate

their feelings because they feel safe. Safety is a key element in having a conflict positive

classroom. Moreover, students were able to encourage one another to accomplish the goal

of the activity. In my experience, when teacher assigns student groups; the students can

potentially be more attentive to their work. However task completion is slightly higher.

What is most notable in letting student autonomy dictate their partnerships, the

most important take away is this: if the teachers goal, as it were in my case, was to create

nm open communication environment, letting students choose their partners for low-

stakes assignments ensured they were able to share their wants and needs. This safe

environment led to fewer conflicts among peers.

The chart below shows the pros and cons of letting students choose their partners.

Part 4 Animal I dentifiers in-group situations

With all this evidence and variables previously presented, one variable remains.

How different students, who fall into various animal identifiers, how do they interact with

the same or different counterparts? There are some patterns that have emerged when

looking through the groups. There are some positive combinations of students animal

identifiers. There are also so volatile and potentially dangerous ones. For example, what

would happen when more than one shark was put in a group?

When Shark Meets Shark

It is interesting to look through any lens how students communicate and handle

conflict. But when you start to uncover how students interact. Lets take Xander from the

previous section. Xander is a self-proclaimed shark. He has strong will to get work done,

but can often times bulldoze over other students to ensure his voice is being heard.

Because of Xanders strong personality, he has often alienated himself from his peers.

I put Xander in a group with another self- proclaimed shark, Eric, and two other

owls. My rationale was the owls could help negotiate and problem solve should conflict

arise between Xander and Eric.

Not surprisingly, the two sharks constantly argued, neither of them listened to one

another, and there was little consensus made. After tirelessly attempting to mediate

between the two other students, Monica and Ashley paired off and worked on their

portion of the work. After all, owls care equally about the work and the relationships of

others. The next class, Xander retreated and displayed qualities of a turtle. He removed

himself from the group and completed his work on his own.

It is not ideal to have two students, who are sharks, work together to complete the

same goal because they have little concern over saving relationships. They will not

compromise. In this case, however, each of the sharks stubbornness and lack of

communication did not serve them well. Now, this was an extreme case. These two

students have a reputation of being difficult to work with, not because they are hard-

working, but because they struggle with perspective taking and listening to their peers.

When debriefing what had transpired, Xander said in a very agitated voice, Ms. DeLuca,

How am I supposed to get anything done when students are not listening to me? When

questioning Eric, he blamed Xander for all of the wrongdoing. Xander refuses to listen

to anyones ideas and would call me names. The two girls in the group both asked me to

Pros Cons

Students will advocate their feelings

and be more honest with friend groups

Students can encourage one another to

accomplish their goals.

Productivity is slightly lower, tasks were

incomplete

Students are more off task

If student motivation is unbalanced, could

result in conflict.

never put them in that situation again. Ashley wrote in her exit card, It was too hard to

talk because Xander and Eric were just yelling [at one another]. Monica responded on

her exit card I cant work with Xander because he doesnt listen and always calls people

mortals who disagree with him. However, this previously mentioned example seems to

be extreme case in which there are other factors involved. What I believed to be

happening was what Elizabeth Cohen refers to a common problem, particularly with

students in middle school. This is referred to in Groupwork as the physical and social

rejection of some members of the group (Cohen, 1994, 58). These two particular

students simply did not get along.

More often with the shark and shark combination is not that extreme. More often

what occurred was that two sharks in a group worked diligently to complete tasks and to

get the work completed. They would often be silent and driven to finish the assignment.

For the historys mysteries project, two self-described forcing sharks, Mark and Charlie,

were task driven and created work with best quality. In video observations, I noticed that

there was little communication, but they agreed on how to create a finished photo. The

equally divided the workload. What was most thought provoking was that they both

thought the other got off task in their exit card. Charlie stated, I had to be a shark make

sure Mark was getting his work done. Marks response nearly paralleled Charlies. I

was a shark to keep my partner focused. True to shark character, both of the students

displayed little regard for personal relationships, and focused solely on the getting the

work completed.

Other combinations to avoid: Turtle/Turtle

Turtles, by nature, retreat when conflict arises. I have often found that students

have described themselves as turtles when they are confused on their assignments.

Because the students in my classroom are not tracked, we have students at different

academic abilities. Looking at the data, it seems, more often than not, when students are

confused, and they tend to be lacking self-advocacy skills, they retreat. The chart below

is a perfect example of such a student. Aaron can often communicate his thoughts

verbally, but his writing is much less proficient. I think that he did not understand the

assignment, nor did he not understand the question I asked in the survey. This is typical

turtle behavior. While this is not an external conflict with his peer, Aarons lack of

understanding the assignment poses an internal conflict. This has led him to withdraw

from his partner as well as from the work.

Aaron

Evaluate your partners

work on the project

How would you rate your

cooperation style?

How would you rate your

partners cooperation style?

IDK, what you mean? Turtle Turtle

There were some potential pitfalls when I grouped students based on animal

identifiers. However, in my experience, I found that there are likewise positive

combinations of animal identifiers when students to work well together.

Positive combinations for work efficiency

Shark, Bear, Owl, & Fox

As teachers, we are trained to recognize when group work is successful and when

it goes awry. Out of my observations, the best groups I found were when there was a

shark, bear, owl and fox. What is striking is how the students communicate with one

another. In video observations of the creating your own government activity, the

conversations between bear, Kylie; Shark Keith; Fox Isaac; and Owl Gretchen was

overheard:

Kylie Bear: What do you want to call our government? How about hashtag

awesome people? We could implement selfies!!!

Shark Keith: How about we call it Keith land? I will rule all (Laughter ensues)

Owl Gretchen I dont think that would work. That doesnt seem right, were not

creating a dictatorship

Shark Keith Im going to create a dictatorship and you will all have to follow

me, minions. Lets move on to question number 2

Fox Isaac: I think Gretchens right. Cant we make the lands a mix of all of our

names?

Kylie Bear: How about Hash tag [combines all names]? Do you think that

could work [gestures towards the rest of the group members, but doesnt make

direct eye contact with Keith].

Fox Isaac/Owl Gretchen: [new name] that works for me.

Shark Keith: I dont like the hash tag part

Owl Gretchen: We have to move on, Keith.

Shark Keith: Fine.

This conversation showed how each of the students communicated their thoughts

equally ensuring that no ones overshadowed. It was well defined that three of them were

in agreement against Keith and they did not want to cause a conflict. Keith did not listen

to their ideas at first, but the fox and the owl jumped in to save the bear. When the shark

was outnumbered, he conceded. What is also noteworthy was the problem solver,

Gretchen, appealed to Keiths academic motivation when she said, We have to move

on. She was negotiating and, intentionally or not, she was appealing to his sense of

wanting to get the assignment done. I also wanted to highlight Kylie who did not want to

speak her mind, because she values relationships. My suspicion is that if Gretchen and

Isaac did not come to her side, she would have conceded.

Other positive combinations

Fox/Fox:

When looking at the data from when the students worked in partnerships, I had

asked the students not only their animal identifier but also how they would identify their

partners.

The two students below describe their experience. They both had positive

experience, even though; Melissa believes that they both waited until the last minute to

complete the work:

Melissa

Evaluate your partners work on

the project

How would you rate

your cooperation

style?

How would you rate your partners

cooperation style?

I think we did okay, despite the

fact we all both lazy until the

second, third, last [minute].

Fox Fox

Jack

Evaluate Your Partners Work on

the project

How would you rate

your cooperation

style?

How would you rate your partners

cooperation style?

[My partner] worked hard

following the script, and she was

eager to finish it.

Fox Fox

I also attributed some of these positive experiences to the fact that students who

work well together typically are focused and motivated to complete assignments. Even

more note-worthy was that throughout the window of my data collection, students

identified themselves as foxes when there was little conflict, and therefore had nothing to

report. This occurred across the exit cards, no matter what the assignment. Amandas

reflection shows that she and her partner were able to work on the task at hand and were

clear on the objective of the assignment.

Evaluate Your Partners Work on the

project

How would you rate

your cooperation style?

How would you rate your

partners cooperation

style?

My partner during this project were

very focused and doing what they were

supposed to be doing.

Fox Fox

Final Thoughts on grouping strategies

In my experience, and from the data, I conclude that, while there are no magic

formulas for grouping students to ensure little conflict or high work production, it is

important to understand potential pitfalls among students. In order to do that, students

and teachers must be able to identify their strengths and weakness when working in

groups. Furthermore, if teachers are striving to create a classroom that requires open

communication, my experience has taught me that changing the group size often and

varying the types partnerships based on animal identifiers will create a safe and open

communicative classroom.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- Sample OSCE Stations DentalDocumento7 pagineSample OSCE Stations DentalEbn Seena90% (10)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Babysitters Club Book ListDocumento5 pagineThe Babysitters Club Book ListLaura92% (12)

- AP Psych All Concept MapsDocumento18 pagineAP Psych All Concept MapsNathan Hudson100% (14)

- Child Labour PPT PresentationDocumento20 pagineChild Labour PPT Presentationsubhamaybiswas73% (41)

- Sample Nursing Cover LetterDocumento1 paginaSample Nursing Cover LetterFitri Ayu Laksmi100% (1)

- Part OneDocumento10 paginePart Oneapi-235360943Nessuna valutazione finora

- Part 2Documento11 paginePart 2api-235360943Nessuna valutazione finora

- ReflectionDocumento4 pagineReflectionapi-235360943Nessuna valutazione finora

- ConclusionDocumento6 pagineConclusionapi-235360943Nessuna valutazione finora

- ReupDocumento2 pagineReupapi-235360943Nessuna valutazione finora

- Great GatsbyDocumento4 pagineGreat Gatsbyapi-235360943Nessuna valutazione finora

- AQA-7131-7132-SP-2023Documento42 pagineAQA-7131-7132-SP-2023tramy.nguyenNessuna valutazione finora

- C/Nursing: Addis Ababa Medical and Business CollegeDocumento3 pagineC/Nursing: Addis Ababa Medical and Business CollegeBora AbeNessuna valutazione finora

- List of Participants: Name Institution Country E-MailDocumento5 pagineList of Participants: Name Institution Country E-MailFrancis MorrisonNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan - HomophonesDocumento3 pagineLesson Plan - Homophonesapi-359106978Nessuna valutazione finora

- STAR Interview GuideDocumento1 paginaSTAR Interview GuideLeona Mae BaylomoNessuna valutazione finora

- FEDERAL PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION SCREENING/PROFESSIONAL TESTSDocumento36 pagineFEDERAL PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION SCREENING/PROFESSIONAL TESTSCh Hassan TajNessuna valutazione finora

- Interview With Mitch Drazin Before and After EditingDocumento3 pagineInterview With Mitch Drazin Before and After Editingapi-285005584Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sptve Techdrwg7 Q1 M4Documento12 pagineSptve Techdrwg7 Q1 M4MarivicNovencidoNicolasNessuna valutazione finora

- Understanding the challenges and opportunities of artificial intelligenceDocumento6 pagineUnderstanding the challenges and opportunities of artificial intelligenceHương DươngNessuna valutazione finora

- Iitm - MDocumento1 paginaIitm - Msachin pathakNessuna valutazione finora

- Q4 Report - OASSPEPDocumento61 pagineQ4 Report - OASSPEPkeziahNessuna valutazione finora

- Child Language Aquisition Revision NotesDocumento31 pagineChild Language Aquisition Revision NotesPat BagnallNessuna valutazione finora

- Role of Educational Resource Centre in Teaching MathematicsDocumento17 pagineRole of Educational Resource Centre in Teaching MathematicsVrinthaNessuna valutazione finora

- Different Software Development Models ExplainedDocumento17 pagineDifferent Software Development Models Explainedcmp256Nessuna valutazione finora

- Research Methodology: 1st SemesterDocumento11 pagineResearch Methodology: 1st SemesterMohammed Khaled Al-ThobhaniNessuna valutazione finora

- 50 Hydraulics Probs by Engr. Ben DavidDocumento43 pagine50 Hydraulics Probs by Engr. Ben DavidEly Jane DimaculanganNessuna valutazione finora

- Letterhead Doc in Bright Blue Bright Purple Classic Professional StyleDocumento2 pagineLetterhead Doc in Bright Blue Bright Purple Classic Professional StyleKriszzia Janilla ArriesgadoNessuna valutazione finora

- Lucena Sec032017 Filipino PDFDocumento19 pagineLucena Sec032017 Filipino PDFPhilBoardResultsNessuna valutazione finora

- Tel: O771629278 Email: Shanmuganathan Sathiyaruban.: B.SC (Eng), Ceng, MieslDocumento4 pagineTel: O771629278 Email: Shanmuganathan Sathiyaruban.: B.SC (Eng), Ceng, MieslsathiyanNessuna valutazione finora

- Jipmer MbbsDocumento3 pagineJipmer MbbsHari SreenivasanNessuna valutazione finora

- Study Skills For SpellingDocumento2 pagineStudy Skills For Spellingapi-277816141Nessuna valutazione finora

- Step-By-Step Analysis and Planning Guide: The Aira ApproachDocumento5 pagineStep-By-Step Analysis and Planning Guide: The Aira ApproachDaniel Osorio TorresNessuna valutazione finora

- Grade 11 Math Lesson Log on FunctionsDocumento4 pagineGrade 11 Math Lesson Log on FunctionsMardy Nelle Sanchez Villacura-Galve100% (2)

- Community Organizing Participatory Research (COPAR)Documento4 pagineCommunity Organizing Participatory Research (COPAR)mArLoN91% (11)

- Simulations A Tool For Testing Virtual Reality in The Language ClassroomDocumento10 pagineSimulations A Tool For Testing Virtual Reality in The Language ClassroomSyed Qaiser HussainNessuna valutazione finora