Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Costa1992 Replytoeysenck

Caricato da

Larisa Tanase0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

17 visualizzazioni5 paginebf

Titolo originale

Costa1992_replytoEysenck

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentobf

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

17 visualizzazioni5 pagineCosta1992 Replytoeysenck

Caricato da

Larisa Tanasebf

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 5

Per son. i ndi oi d. Di f l Vol. 13, No. 8, pp.

861- 865, 1992

Printed in Great Britain

0191-8869/ 92 $5.00 +0. 00

Pergamon Press Ltd

REPLY TO EYSENCK*

PAUL T. COSTA J R and ROBERT R. MCCRAE

Gerontology Research Center, National Institute on Aging, NIH Baltimore, MD, U.S.A.

(Received 4 J anuary 1992)

Summary-In this response to Eysencks comments we argue that a contemporary review of the literature

would favor the five-factor model; we attempt to explain the observed correlations between scales that

measure different factors; and we reiterate our view that the systematic description of personality must

precede, not follow, personality theory.

In the interest of brevity, we might limit our reply to Eysenck (1992) to an invitation to the reader

to re-read our original article (Costa & McCrae, 1992); most of the points he makes are anticipated

and answered there. For example, he discusses the Zuckerman, Kuhlman, Thornquist and Kiers

(1991) article and comments that their five factors do not match ours very well. We acknowledge

this, and showed how a re-rotation could substantially improve the match. He points out that

cross-observer correlations for Conscientiousness (C) are derisorily small, noting a 0.30 between

peer raters. But Table 2, from which he extracts this figure, also shows peer/self correlations of

0.46 for C-higher than those found for the uncontested dimensions of Neuroticism (N) (0.33) and

Extraversion (E) (0.43). There are some points, however, we would like to clarify here.

In our original article, we argued that the dimensions of the five-factor model are real, pervasive,

universal, and biologically based. In his reply, Eysenck grants these points and acknowledges that

they are necessary features of basic dimensions of personality, but argues that,; they are not

sufficient: they do not distinguish the five-factor model from its competitors-at least from

Eysencks three-factor model. He is of course correct in one sense. If we assume that the three-factor

model is a subset of the five-factor model [Psychoticism (P) being viewed as a combination of low

Agreeableness (A) and low C], then the dimensions of the three-factor model must also be real,

pervasive, universal, and biologically based. We are happy to grant this.

The three-factor model, however, is not comprehensive, most obviously because it does not

account for traits related to Openness (0). By listing a catalog of related traits, we intended to show

that this dimension has recurred in too many conceptualizations to be ignored. By reviewing its

minimal correlation with IQ, we have shown that 0 cannot be reduced to intellectual ability. At

one time, Eysenck suggested that 0 represents possibly the opposite end of a continuum to

psychoticism (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1985, p. 138), but in fact the correlation between 0 and P is

0.05, N = 586, NS (McCrae & Costa, 1985). It would seem that, at a minimum, Eysenck should

recognize the need for a four-factor model: N, E, P and 0.

We concur with Eysencks view that purely psychometric criteria cannot resolve the issue of

which factors are basic (although Everetts 1983 formalization of the criterion of factor replicability

is a marked advance over eigenvalue rules). Ultimately, the decision of what factor structure is best

requires scientific judgment on the recurrence of regular patterns that make sense of the broadest

range of data.

Eysenck claims that the five-factor model has not been recovered by researchers outside the

narrow circle of five-factor enthusiasts, and cites a 1983 review by Royce and Powell as evidence

of the wider acceptability of the three-factor model. It is possible that, as of 1983, there was more

evidence in favor of a three-factor model than a five-factor model, but much has changed since

then. Perhaps we should set aside the voluminous research on trait adjectives (e.g. Goldberg, 1989)

and adjective-based scales (e.g. Trapnell & Wiggins, 1990; Brand & Egan, 1989), because the five

factors were first discovered in analyses of adjectives, and these studies could be considered

*Personality and I ndividual Differences, 13, 661-613 (1992).

861

862 PAUL T. COSTA JR and ROBERT R. MCCRAE

replications instead of independent rediscoveries. We could also set aside research using Normans

(1963) rating scales (e.g. Yang & Bond, 1990) because these scales were based on analyses of trait

adjectives, and studies which employed the NE0 Personality Inventory (Costa & McCrae, 1985;

McCrae, 1989) because it was developed explicitly to measure the five-factor model. A contempo-

rary meta-analysis would still have to consider Amelang and Borkenau (1982), Krug and Johns

(1986), Conn and Ramanaiah (1990), Noller, Law and Comrey (1987, especially as reanalyzed by

Boyle, 1989), Zuckerman, Kuhlman, Thornquist and Kiers (1991, especially as reanalyzed in our

article), Loehlin (1987), Botwin and Buss (1989), and Lanning and Gough (1991)-all studies in

which most or all of the five factors were identified in analyses of a wide variety of instruments

that had originated in other contexts. Like Wiggins and Trapnell (in press), we believe the weight

of the evidence has now clearly shifted in favor of the five-factor model.

INTERCORRELATIONS AMONG THE FACTORS

One point of Eysencks commentary is likely to cause confusion. Early in his article he suggests

that C is not a separate factor; instead, it is a rather small part of P, as illustrated in his Fig. l(a).

Later, he notes the sizeable correlation (- 0.49) between C and N domain scales of the NEO-PI-R,

and suggests that traits related to C can be explained theoretically as aspects of N. Perhaps he

intended to say that C is a blend of low P and low N (just as we have argued that P is a blend

of low C and low A).

More generally, his point is that the five do not really represent the highest order, and thus the

most basic, factors. He is not alone in this view: Digman (1991), a well-known advocate of the

five-factor model, has also noted correlations between scales measuring the five factors and

suggested that there may be two higher-order factors, one contrasting N with A and C, the other

combining E and 0. He has argued that the first superfactor might represent Socialization, the

second, Self-actualization.

We do not share this view; we think that the five dimensions themselves are essentially orthogonal

and irreducible. How, then, do we account for the fact that scales measuring the five factors are

often intercorrelated? There are two explanations. First, biases in implicative meaning can create

spurious correlations. The factor that Digman interprets as Socialization might equally well be

characterized as evaluation: A and C are desirable characteristics, whereas N is undesirable.

Individuals who view themselves positively will tend to rate themselves as somewhat higher in A

and C and lower in N than they actually are. This bias is not necessarily shared by other observers,

and that may account for the fact that orthogonal factor scores have higher cross-observer validity

than do (spuriously) oblique factor scores (McCrae & Costa, 1989).

The other reason is substantive. As we noted in our original paper, personality traits are not

neatly clustered into discrete domains. Many, perhaps most, traits overlap two or more of the

separate factors; for example, interpersonal warmth is related to both E and A. If an instrument

samples traits broadly, it is likely to include many such mixed traits, and scales based on unit

weighting (like the domain scales of the NEO-PI-R) will probably show intercorrelations of some

kind.*

If these intercorrelations were consistent across instruments-if many different samplings of

traits led to the same pattern of associations among domains-we might well conclude that the

five factors were themselves oblique, correlated in ways that could be meaningfully summarized

by higher-order factors. But they are not.

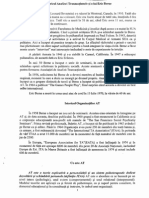

Table 1 shows second-order analyses of three instruments intended to measure the five-factor

model: a set of adjective scales developed by Goldberg (1989) and administered in a transparent

format, that is, with similar items grouped together; another set of adjective scales developed by

Trapnell and Wiggins (1990) to extend their earlier work on the interpersonal circumplex; and the

NEO-PI-R. All three have shown convergent and discriminant validity as measures of the five

factors. The data are taken from peer ratings of participants in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study

*Where uncorrelated measures of the factors are needed, we recommend orthogonal factor scores (cf. Table 2 in our original

article). These are calculated automatically in NEO-PI-R computer-administered testing, and scoring weights from the

standardization sample are provided in the NEO-PI-R manual.

Reply to Eysenck

Table I. Second-order factor analyses of three measures of the live-factor model

Two-factor solution Three-factor solution

Scale I II I II III

Transparent Trait Rating Form

Low Emotional Stability (N) 0.92 -0.19 0.89 -0.03 -0.29

Extraversion (E) -0.10 0.78 -0.17 0.94 0.14

Intellect (0) -0.29 0.81 -0.23 0.46 0.71

Agreeableness (A) -0.84 0.29 -0.87 0.31 0.14

Conscientiousness (C) -0.35 0.63 -0.21 0.02 0.91

Revised Interpersonal Adjective Scales-Big Five Versionb

Neuroticism (N) 0.79 -0.11 0.90 -0.15 0.02

Dominance (E) 0.25 0.81 0.10 0.91 -0.01

Openness (0) -0.44 0.49 -0.11 0.08 0.95

Love (A) -0.87 -0.01 -0.81 -0.14 0.30

Conscientiousness (C) -0.33 0.67 -0.30 0.55 0.41

Revised NE0 Personality Inventoryc

Neuroticism (N) 0.85 -0.10 0.59 -0.09 -0.61

Extraversion (E) -0.15 0.85 0.03 0.88 0.23

openness (0) -0.06 0.90 -0.21 0.88 -0.10

Agreeableness (A) -0.66 0.18 -0.94 0.10 0.06

Conscientiousness (C) -0.72 0.00 -0.05 0.06 0.92

863

These are varimax-rotated principal components from single peer ratings; see Costa and McCrae

(in press) for details. Loadings greater than 0.40 are given in boldface.

Goldberg (1989) N = 137.

bTrapnell and Wiggins (1990) N = 156.

Costa, McCrae and Dye (1991) N = 227.

of Aging (Costa & McCrae, in press); factors have been rearranged and reflected to simplify

comparisons.

The first two columns show a two-factor solution. Digman (1991) predicted a Socialization factor

of N versus A and C and a Self-actualization factor of E and 0. This pattern is indeed found in

the NEO-PI-R data, but not in the other two instruments. In the two adjective instruments, the

first factor is N versus A; C joins E and 0 in the second factor. Digmans two-factor solution is

apparently not replicable across instruments.

The last three columns show a three-factor solution that might be consistent with Eysencks

model. Presumably he would hypothesize N, E, and P factors, with P defined chiefly by low A.

From his commentary, it appears that he would predict that C should show negative loadings on

both the N and P factors and that 0 would join with E. But none of the three instruments shows

this pattern. The first factor in each is N versus A; the second shows E twice with 0, but once

with C. The third factor is C with 0, 0 with C, or C versus N. Readers who wish to analyze the

self-report data in Costa, McCrae and Dyes (1991) Table 5 will find yet another three-factor

solution: C and E versus N, E and 0, and A alone. Nowhere in any of the analyses is a P-like

factor defined solely by low A with low C to be found.

In short, two-factor solutions are not replicable. Three-factor solutions are not replicable. Only

five-factor solutions have been replicated time after time, in diverse instruments (cf. Borkenau &

Ostendorf, 1990). That is why five factors are basic.

THE ROLE OF THEORY

In our article, we rejected the idea that personality structure should be determined by theory,

noting particularly that our knowledge of neuroscience is too primitive to guide decisions about

personality description. Predictably, Eysenck rises to the defense of biological theories of

personality. We share with him the view that progress is being made in these areas, and we fully

support research on personality and psychobiology. We remain skeptical, however, that sufficient

progress has been made to allow much contribution to the issue of basic dimensions of personality.

In our view, outside a small circle of Eysenckian enthusiasts, there is little support for any

particular psychobiological theory of personality. Block (1977) summarized criticisms of the P scale

and its theoretical relation to psychosis and psychopathy. A recent chapter by Amelang and Ullwer

(1991) reported an ambitious attempt to replicate findings on the psychophysiological, perceptual,

learning, and motor correlates of E in a German sample. The authors concluded that none of

the hypotheses concerning the excitation-inhibition-balance could be confirmed (p. 310). Gray

(1991), who has devoted a distinguished career to the study of personality and neuropsychology,

864 PAUL T. COSTA J R and ROBERT R. MCCRAE

freely admitted that human individual differences . . . are still difficult to link to the workings of

the brain (p. 126). Surely this is the area in which premature crystallizations of spurious

orthodoxy are to be feared.

Eysencks ultimate goal is the creation of a paradigm for personality psychology that can guide

fruitful normal science. We concur in the need for such a paradigm, but believe that at this point

in the development of our science what is needed is not theory, but a systematic method of

description. There has been more than enough description of individual differences, but little

coherent system. The paradigm that has brought most order to this field is the one which seeks

the broadest possible themes, the most common and fundamental dimensions, and only after

exhausting their possibilities moves on to add new dimensions of comparable breadth and

significance. This approach, of course, is precisely that adopted by Eysenck in his ground-breaking

emphasis on E and N, and later P (Costa & McCrae, 1986). We regard the five-factor model not

as a competing paradigm, but as the result of normal science within Eysencks own descriptive

paradigm.

REFERENCES

Amelang, M. & Borkenau, P. (1982). Uber die faktorielle Struktur und exteme Validitlt einiger Fragebogen-Skalen zur

Erfassung von Dimensionen der Extraversion und emotionalen Labilitlit [On the factor structure and external validity

of some questionnaire scales measuring dimensions of extraversion and neuroticism]. Zeirschrifi ftir Differentielle und

Diagnostische Psychologie, 3, 119-146.

Amelang, M. & Ullwer, U. (1991). Correlations between psychometric measures and psychophysiological as

well as experimental variables in studies on extraversion and neuroticism. In Strelau, J. & Angleitner, A.

- (Eds), &plorations in temperament: I nternational perspectives of theory and measurement (pp. 287-316). New York:

Plenuni. !; :;

Block, J. (1977). P scale and psychosis: Continued concerns. J ournal of Abnormal Psychology, 86, 431-434.

Borkenau, P. & ,Ostendorf, F. (1990). Comparing exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis: A study on the 5-factor

model of personality. Personality and I ndividual Differences, II, 5 15-524.

Botwin, M. D. & Buss, D. M. (1989). The structure of act report data: Is the five-factor model recaptured? J ournal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 988-1001.

Boyle, G. J. (1989). Re-examination of the major personality-type factors in the Cattell, Comrey and Eysenck scales: Were

the factor solutions by Noller et al. optimal? Personality and I ndividual Differences, I O, 1289-1299.

Brand, C. R. & Egan, V. (1989). The Big Five dimensions of personality? Evidence from ipsative, adjectival

s@f-&%utions. Personali& and I ndividual-Differences, 10, 1165-l l?l.

Comi; S. R. & Ramanaiah. N. V. (1990). Factor structure of the Comrev Personality Scales, the Personality Research

F&m-E, and the five-factor model. I &ychological Reports, 67, 627432.

Costa, P. T. Jr & McCrae, R. R. (1985). The NE0 Personality I nventory manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment

Resources.

Costa, P. T. Jr & McCrae, R. R. (1986). Major contributions to personality psychology. In Modgil, S. & Modgil, C. (Eds),

Hans Evsenck: Consensus and controversy (PP. 63-72, 86, 87). Barcombe, Lewes, Sussex. England: Falmer.

_ __

Costa, P. T: Jr & McCrae, R. R. (in press). Trait psychology comes of age. In Sonderegger, T. B. (Ed.), Nebraska symposium

on motivation: Psychology and aging. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Costa, P. T. Jr & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Four ways five factors are basic. Personality and I ndividual Differences, 13(6),

653-665.

Costa, P. T. Jr, McCrae, R. R. & Dye, D. A. (1991). Facet scales for Agreeableness and Conscientiousness: A revision

of the NE0 Personality Inventory. Personality and I ndividual Differences, I 2, 887-898.

Digman, J. M. (August, 1991). The Big Five: Up, down, and beyond. In Strack, S. (Chair), Beyond the bigfive. Symposium

presented at the American Psychological Association Convention, San Francisco.

Everett, J. E. (1983). Factor comparability as a means of determining the number of factors and their rotation. Multivariate

Behavioral Research, 18, 197-218.

Eysenck, H. J. (1992). Four ways five factors are not basic. Personality and I ndividual Differences, 13, 667-673.

Eysenck, H. J. & Eysenck, M. (1985). Personality and individual differences. London: Plenum.

Goldberg, L. R. (June, 1989). Standard markers of the Big Five factor structure. Paper presented at the First I nternational

Workshop on Personality Language, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Gray, J. A. (1991). The neuropsychology of temperament. In Strelau, J. & Angleitner, A. (Eds), Explorations in temperament:

I nternational perspectives on theory and measurement (pp. 105-128). New York: Plenum.

Krug, S. E. & Johns, E. F. (1986). A large scale cross-validation of the second-order personality structure defined by the

16PF. Psychological Reports, 59, 683-693.

Lanning, K. & Gough, H. G. (1991). Shared variance in the California Psychological Inventory and the California Q-Set.

J ournal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 59&606.

Loehlin, J. C. (1987). Heredity, environment, and the structure of the California Psychological Inventory. Mulfivariate

Behavioral Research, 22, 137-148.

McCrae, R. R. (1989). Why I advocate the five-factor model: Joint analyses of the NEO-PI and other instruments. In Buss,

D. M. & Cantor, N. (Eds), Personality psychology: Recent trends and emerging directions (pp. 237-245). New York:

Springer-Verlag.

McCrae, R. R. & Costa, P. T. Jr (1985). Comparison of EPI and Psychoticism scales with measures of the five-factor model

of personality. Personality and I ndividual D@erences, 6, 587-597.

Reply to Eysenck 865

McCrae, R. R. & Costa, P. T. Jr (1989). Different points of view: Self-reports and ratings in the assessment of personality.

In Fornas. J. P. & Innes. M. J. (Eds), Recent advances in social psychology: An international perspective (pp. 429439).

Amstezam: Elsevier Science Publishers.

Noller, P., Law, H. & Comrey, A. L. (1987). Cattell, Comrey, and Eysenck personality factors compared: More evidence

for the five robust factors? J ournal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 775-782.

Norman, W. T. (1963). Toward an adequate taxonomy of personality attributes: Replicated factor structure in peer

nomination personality ratings. J ournal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 66, 574583.

Royce, J. R. & Powell, A. (1983). Theory ofpersonality and individualdifferences: Factors, systems, andprocesses. Englewood

Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Trapnell, P. D. & Wiggins, J. S. (1990). Extension of the Interpersonal Adjective Scales to include the Big Five dimensions

of personality. J ournal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 781-790.

Wiggins. J. S. & Trapnell, P. D. (in press). Personality structure: The return of the Big Five. In Brigas, S. R., Hogan, R.

-& Jones, W. H. (Eds), Handbook of personality psychology. New York: AcademicPress. --

Yang, K. & Bond, M. H. (1990). Exploring implicit personality theories with indigenous or imported constructs: The

Chinese case. J ournal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 1087-1095.

Zuckerman, M., Kuhlman, D. M., Thornquist, M. & Kiers, H. (1991). Five (or three) robust questionnaire scale factors

of personality without culture. Personality and I ndividual Differences, 12, 929-941.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- OutDocumento40 pagineOutLarisa TanaseNessuna valutazione finora

- Handout at 101Documento38 pagineHandout at 101Larisa TanaseNessuna valutazione finora

- Reviews Journal ArticlesDocumento2 pagineReviews Journal ArticlesMina KobilarevNessuna valutazione finora

- The British Journal of Developmental Psychology Mar 2001 19, Proquest CentralDocumento16 pagineThe British Journal of Developmental Psychology Mar 2001 19, Proquest CentralLarisa TanaseNessuna valutazione finora

- Childhood 2013 Majors 550 65Documento17 pagineChildhood 2013 Majors 550 65Larisa TanaseNessuna valutazione finora

- 84783046Documento20 pagine84783046Larisa TanaseNessuna valutazione finora

- Goldberg - Big Five Markers Psych - Assess.1992Documento17 pagineGoldberg - Big Five Markers Psych - Assess.1992Larisa TanaseNessuna valutazione finora

- AHMT 16992 Perceived Parenting Styles Differ Between Genders But Not B 012611Documento6 pagineAHMT 16992 Perceived Parenting Styles Differ Between Genders But Not B 012611Larisa TanaseNessuna valutazione finora

- International Journal of Behavioral Development 2004 Gleason 204 9Documento7 pagineInternational Journal of Behavioral Development 2004 Gleason 204 9Larisa TanaseNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 PBDocumento10 pagine1 PBLarisa TanaseNessuna valutazione finora

- Costa1992 ReplytoeysenckDocumento5 pagineCosta1992 ReplytoeysenckLarisa TanaseNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 s2.0 S0001879112000358 MainDocumento12 pagine1 s2.0 S0001879112000358 MainLarisa TanaseNessuna valutazione finora

- 2012 660361Documento25 pagine2012 660361Larisa TanaseNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 s2.0 S0001879112000358 MainDocumento12 pagine1 s2.0 S0001879112000358 MainLarisa TanaseNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Effects of Social Media in Academic Performance of Selected Grade 11 Students in STI College Novaliches SY 2018-2019Documento28 pagineEffects of Social Media in Academic Performance of Selected Grade 11 Students in STI College Novaliches SY 2018-2019Aaron Joseph OngNessuna valutazione finora

- INSEADDocumento3 pagineINSEADsakshikhurana52Nessuna valutazione finora

- Reflection EssayDocumento8 pagineReflection Essayapi-193600129Nessuna valutazione finora

- Chakras EnneagramDocumento3 pagineChakras Enneagramfernandeantonio7961100% (4)

- Learning Action Cell (LAC) Plan: Topic: 21st Century Skills and ICT Integration in Instruction and AssessmentDocumento1 paginaLearning Action Cell (LAC) Plan: Topic: 21st Century Skills and ICT Integration in Instruction and AssessmentKenneth Cyril Teñoso100% (1)

- Impact of Smartphone Addiction in The Academic Performance of Grade 12 Students in Santa Rosa Science and TECHNOLOGY HIGH SCHOOL (S.Y. 2019-2020)Documento8 pagineImpact of Smartphone Addiction in The Academic Performance of Grade 12 Students in Santa Rosa Science and TECHNOLOGY HIGH SCHOOL (S.Y. 2019-2020)Prospero, Elmo Maui R.50% (4)

- Nursing Theories and Their WorksDocumento4 pagineNursing Theories and Their WorksCharm Abyss la Morena0% (1)

- 12 Characteristics of An Effective TeacherDocumento4 pagine12 Characteristics of An Effective TeacherRamonitoElumbaringNessuna valutazione finora

- Art Direction Mood BoardDocumento13 pagineArt Direction Mood BoardBE-K.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Organizational Behaviour - Difficult TransitionsDocumento9 pagineOrganizational Behaviour - Difficult TransitionsAravind 9901366442 - 990278722486% (14)

- God, Abraham, and The Abuse of Isaac: Erence RetheimDocumento9 pagineGod, Abraham, and The Abuse of Isaac: Erence RetheimIuanNessuna valutazione finora

- Assignment 2 For 2b Mathematical Content Knowledge Last EditionDocumento9 pagineAssignment 2 For 2b Mathematical Content Knowledge Last Editionapi-485798829Nessuna valutazione finora

- Njau - Challenges Facing Human Resource Management Function at Kenyatta National HospitalDocumento64 pagineNjau - Challenges Facing Human Resource Management Function at Kenyatta National HospitalAdrahNessuna valutazione finora

- Ateeq CVDocumento4 pagineAteeq CVNasir AhmedNessuna valutazione finora

- Color ConsciousnessDocumento4 pagineColor ConsciousnessM V29% (14)

- Leasson Plan 4Documento31 pagineLeasson Plan 4Eka RoksNessuna valutazione finora

- Emalee CawteDocumento2 pagineEmalee Cawteapi-401329529Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Big Book of ACT Metaphors-2014-1Documento250 pagineThe Big Book of ACT Metaphors-2014-1cristian vargas100% (3)

- Operations StrategyDocumento41 pagineOperations StrategyClarisse Mendoza100% (1)

- Resume BagoDocumento4 pagineResume Bagoapi-26570979Nessuna valutazione finora

- Tinnitus Causes and TreatmentDocumento3 pagineTinnitus Causes and TreatmentTinnituscausesandtreatment Tinnituscausesandtreatment100% (1)

- Summative Task On Multiplication (An Array City) - 18th November, 2021Documento4 pagineSummative Task On Multiplication (An Array City) - 18th November, 2021Spoorthy KrishnaNessuna valutazione finora

- VETASSESS Update On Application Processes For Skills Assessments For General Professional OccupationsDocumento3 pagineVETASSESS Update On Application Processes For Skills Assessments For General Professional Occupationsaga_andreNessuna valutazione finora

- Mission of Pepsico BD: Transcom Beverage LTDDocumento30 pagineMission of Pepsico BD: Transcom Beverage LTDBISHAASH বিশ্বাসNessuna valutazione finora

- Rebecca Comay, "The Sickness of Tradition: Between Melancholia and Fetishism"Documento17 pagineRebecca Comay, "The Sickness of Tradition: Between Melancholia and Fetishism"tabrasmsNessuna valutazione finora

- Methods and Techniques: The K-12 ApproachDocumento45 pagineMethods and Techniques: The K-12 Approachlaren100% (1)

- An Open Letter To President Benson and The Board of RegentsDocumento6 pagineAn Open Letter To President Benson and The Board of RegentsWKYTNessuna valutazione finora

- Note-Taking in InterpretingDocumento11 pagineNote-Taking in InterpretingмаликаNessuna valutazione finora

- Specific Learning DisabilitiesDocumento22 pagineSpecific Learning Disabilitiesapi-313062611Nessuna valutazione finora

- Bacalan DoDocumento5 pagineBacalan DoThalia Rhine AberteNessuna valutazione finora