Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Untitled

Caricato da

api-2287147750 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

44 visualizzazioni9 pagineClearinghouses were a stabilizing influence during the 2008-2009 global credit crisis. Since then, regulators worldwide have conferred more responsibilities on clearinghouses. Although instances are rare, clearinghouses have defaulted in the past.

Descrizione originale:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoClearinghouses were a stabilizing influence during the 2008-2009 global credit crisis. Since then, regulators worldwide have conferred more responsibilities on clearinghouses. Although instances are rare, clearinghouses have defaulted in the past.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

44 visualizzazioni9 pagineUntitled

Caricato da

api-228714775Clearinghouses were a stabilizing influence during the 2008-2009 global credit crisis. Since then, regulators worldwide have conferred more responsibilities on clearinghouses. Although instances are rare, clearinghouses have defaulted in the past.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 9

Clearinghouses Are Raising Their

Game--But They Are Not Risk-Free

Primary Credit Analysts:

Thierry Grunspan, Paris (33) 1-4420-6739; thierry.grunspan@standardandpoors.com

Samira Mensah, Johannesburg (27) 11-214-1995; samira.mensah@standardandpoors.com

Secondary Contacts:

Charles D Rauch, New York (1) 212-438-7401; charles.rauch@standardandpoors.com

Giles Edwards, London (44) 20-7176-7014; giles.edwards@standardandpoors.com

Table Of Contents

A Brief History Of Clearinghouse Failure

Types Of Exposures to Clearinghouses

New Regulation Has Strengthened The Quality Of Financial Safeguards

WWW.STANDARDANDPOORS.COM/RATINGSDIRECT JUNE 5, 2014 1

1328907 | 300051529

Clearinghouses Are Raising Their Game--But They

Are Not Risk-Free

Throughout the 2008-2009 global credit crisis, clearinghouses were a stabilizing influence for unnerved investors and

traders. All the clearinghouses we rate completed their clearing and settlement obligations in a timely manner and

without incident of loss to either themselves or their members. Since then, regulators worldwide have conferred more

responsibilities to clearinghouses, also known as central counterparties (CCPs), recognizing that their resilience in a

crisis could aid the stability of the financial system. The U.S., for example, introduced mandatory clearing of

over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives by CCPs in 2013 as part of the Dodd-Frank Act, and the EU plans to follow in 2015

under the European Market Infrastructure Regulation (EMIR). As a result, the members of clearinghouses and

non-members will face increased exposure to CCPs.

Although clearinghouses are in many ways better equipped than individual banks to handle counterparty risk, they are

not risk-free. Although instances are rare, clearinghouses have defaulted in the past. Furthermore, the regulations on

CCPs in the U.S. and the EU, rather than eradicating risks for the financial system as a whole, are in our view

transferring risks to clearinghouses.

Overview

Standard & Poor's believes clearinghouses are generally well positioned to meet the new responsibilities and

risk that regulators worldwide are transferring to them, particularly in the clearing of over-the-counter (OTC)

derivatives in the U.S. and the EU.

Regulatory changes under Basel III recognize this risk and require banks to maintain capital against their

exposure to clearinghouses.

Although the new regulation has strengthened the quality of financial safeguards, especially in the EU and in

the U.S., we believe that competition for business may tempt some clearinghouses to lower their financial

safeguards.

In recognition of the growing exposures that clearinghouses handle, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS)

requires banks to maintain capital against their exposure to CCPs under the new Basel III regime. This is a new

development compared with the former Basel II regime, under which exposures to CCPs are viewed as risk-free.

Standard & Poor's Ratings Services, which surveils 13 clearinghouse operators worldwide (mainly as part of rating their

parents), considers that regulation aimed at strengthening the robustness of financial safeguards for CCPs is a positive

development. We nevertheless believe the quality of financial safeguards could increasingly differ among

clearinghouses as they compete with each other for business, with some tempted to relax financial safeguards to

attract new customers.

WWW.STANDARDANDPOORS.COM/RATINGSDIRECT JUNE 5, 2014 2

1328907 | 300051529

A Brief History Of Clearinghouse Failure

Although rare, clearinghouses can and do fail. In some cases, clearinghouses have suffered a "sudden death" by being

unable to complete settlement obligations in a timely manner. In other cases, they have suffered a slow death by

gradually losing business from their associated exchange if traders migrate to a competing venue.

Among the three most famous clearinghouse failures in recent history, the Caisse de Liquidation, an independent

commodities clearinghouse in France, was hit by a sharp and sudden correction in the price of sugar in November

1974. The Caisse was slow to react and several members, including one with a very large position in sugar, did not

meet their margin calls. Consequently, the French Ministry of Commerce closed the market.

In a second case, the Kuala Lumpur Commodities Clearing House was hit by a price squeeze in palm oil when one

large member tried to corner the market in that contract in February 1984. The clearinghouse was slow to respond to

the unusual trading activity. When it did adjust margin requirements, several large players defaulted and trading was

suspended.

Third, the Hong Kong Futures Guarantee Corporation provided a settlement guarantee to trades conducted on the

Hong Kong Futures Exchange, home of the Hang Seng Index futures contract, one of the most actively traded stock

index contracts outside the U.S. It was not affiliated with the clearinghouse, ICCH (Hong Kong) Ltd. In October 1987,

the stock market crashed and the guarantee corporation had insufficient resources (only HK$15 million of capital) to

handle the massive member defaults. A HK$2.0 billion rescue package was put in place, consisting ofHK$1.0 billion

from the Hong Kong government, HK$500 million from a group of local banks, and HK$500 million from the

shareholders of the guarantee corporation.

Beyond these three high-profile cases, there have been a number of close calls; the most infamous being the Singapore

International Monetary Exchange (SIMEX). In February 1995, Nick Leeson, a trader at Barings Bank, had a 827

million losing position in futures contracts linked to the Nikkei 225 stock index. When Barings was unable to meet the

margin call, the bank collapsed and nearly brought down the SIMEX with it.

Types Of Exposures to Clearinghouses

Two different groups are exposed to a failure at a clearinghouse. The first are their members--that is entities (banks or

brokers) that clear their trades directly with the CCP, without any intermediary. Clearing members clear trades for their

own account, as well as trades on behalf of their customers. The second are non-clearing members, customers of these

member entities, who rely on clearing members to clear their trades.

Members of clearinghouses are exposed to two broad categories of risks in the event a CCP defaults or ceases to

operate:

Trade exposures, of which there are two types of exposure: collateral on deposit and derivative replacements costs;

Default contributions.

WWW.STANDARDANDPOORS.COM/RATINGSDIRECT JUNE 5, 2014 3

1328907 | 300051529

Clearinghouses Are Raising Their Game--But They Are Not Risk-Free

Non-members' exposure to CCPs depends on the segregation of collateral the client posts to the clearing member.

Below, we detail these risks as well as the various regulatory requirements related to these risks under Basel III

Members' trade exposures

Collateral on Deposit. Clearinghouses require their members to post an initial (or original) margin, which acts as

performance bond or good faith deposit in the event the member defaults. Initial margin is typically designed to cover

the potential overnight (or multiday) change in price in the defaulted member's outstanding portfolio at the

clearinghouse. Initial margin collateral is typically in the form of cash or high-quality securities that the clearinghouse

collects at least on a daily basis. If this collateral is not held in a bankruptcy-remote manner (for instance, through a

custodial account held for the beneficial interest of the member), then these member assets are at risk. This is true

whether the member clears for its own account or for those of its clients.

In addition to initial margin, there is also variation margin, which represents the daily or more frequent mark-to-market

of the members' open positions. The purpose of this is to prevent members from building sizable losses on their open

positions. The clearinghouse does not hold the variation margin as it does initial margin. Instead, the clearinghouse is

an intermediary: it collects from the losers and pays the winners.

Recent legislation in the U.S., through the Dodd-Frank Act and in Europe through the European Market Infrastructure

Regulation (EMIR) requires CCPs to institute recovery and resolution (R&R) plans that are akin to living wills. To

improve their prospects in the recovery phase after a default by a major member, some clearinghouses are introducing

extra layers of protection to their own solvency. These typically involve moving any residual loss (the loss arising after

the financial safeguard package is exhausted) from the clearinghouse back to the non-defaulting members. For

example, clearinghouse rulebooks may contain loss allocation rules in which the residual loss is allocated among the

non-defaulting members and a wind-down of clearing services initiated. Loss allocation rules typically include variation

margin haircuts. Indeed, since February 2014, U.K.-regulated clearinghouses have been legally required to have loss

allocation procedures for clearing risks in their rulebooks.

We believe that a CCP would invoke loss-allocation rules only as a last resort in a desperate situation. The rated

clearinghouses have put in place financial safeguard packages that in our view protect themselves from losses arising

from member defaults in all but the most extreme market conditions. This is an important factor in our ratings on these

institutions. For this reason, we consider that the prospect of a rated clearinghouse exhausting its financial safeguard

package and invoking its loss-allocation rules is remote.

Derivatives Replacement Costs. If a derivatives clearinghouse fails, the surviving members will need to replace their

outstanding derivative positions at current market prices. For example, a bank that has centrally cleared an

over-the-counter (OTC) interest rate swap with SwapClear (an unrated unit of LCH.Clearnet Group) is exposed to loss

in the event the CCP fails. The bank's potential loss would be the difference between the current market price for a

contractually similar interest rate swap (i.e., the market price at the time the swap is actually replaced with another

counterparty than the CCP) and the market price of the swap at the last time the bank has received (or posted)

variation margin from the CCP before it failed.

The Basel III regulations require a bank to maintain a 2% regulatory risk-weight against its exposures to these two

types of trading risks if it is a member of a "qualified" CCP (meaning the CCP meets minimum CPSS/IOSCO technical

standards). If it is a member of a "non-qualified" CCP, the risk weight is 20% because BIS views the exposure as riskier.

WWW.STANDARDANDPOORS.COM/RATINGSDIRECT JUNE 5, 2014 4

1328907 | 300051529

Clearinghouses Are Raising Their Game--But They Are Not Risk-Free

Default fund contributions. Most clearinghouses require their members to contribute to a guaranty fund, also known as

a default fund or clearing fund. When a member defaults, the clearinghouse expeditiously transfers or closes out the

defaulting member's open positions using its collateral--the defaulting member's initial margin and guarantee fund

contributions--to cover any losses. If the large losses exceed these amounts, the clearinghouse will use other financial

resources, including the guaranty fund contributions of the non-defaulting members, in the form laid down in its rule

books. They may also be permitted to assess the non-defaulting members to replenish the guaranty fund.

A clearinghouse's guaranty fund and assessment powers introduce "mutuality of risk" among the members. Guaranty

fund contributions are much riskier than trade exposures because they do not necessarily require the CCP to default

for banks to lose their guaranty fund contributions, either in part or in full. Clearing members could lose part of their

contribution in a scenario under which another clearing member defaults, with the CCP still having enough resources

to keep operating.

This is an important factor in our ratings on clearinghouses. Mutuality of risk provides a powerful incentive to the

members to self-police their trading activities because they are at risk in the event that another member defaults. If a

clearinghouse taps its guaranty fund or requests its members to replenish the guaranty fund as permitted in its

rulebook, we would not consider this to be an event of default.

This is what happened at the unrated Korea Exchange in December 2013, when a small brokerage company, HanMag

Securities, entered erroneous trades on the Kospi 200 Index Options contract and suffered losses that exceeded its

capital base. HanMag asked the exchange to cancel the orders, but the request was denied. The losses caused by

HanMag were so large that they exceeded its collateral (initial margin and guaranty fund contribution) on deposit at

the exchange's clearinghouse subsidiary. The clearinghouse did not use any of its own financial resources

("skin-in-the-game") to cover these losses. Instead, it used reserves set aside in the Joint Compensation Fund (i.e.,

guaranty fund) into which all members had contributed. While the clearinghouse acted within its own rules, the

non-defaulting members were upset because their funds, not those of the exchange, were prioritized to cover the

losses caused by a member default. Since this incident, Korea Exchange has amended and updated its clearinghouse

rules so that part of its own capital now stands before the guaranty funds in the payment waterfall. We also expect that

members of CCPs more generally have reminded themselves of the various default waterfalls that are in force.

Reflecting the riskiness of default fund contributions, bank regulators apply a charge of up to 100% in some instances

(meaning that guaranty fund contributions are, in essence, fully deducted from banks' regulatory capital in some

cases).

Non-member exposure to clearinghouses and clearing members

A trading firm that is not a clearing member of a clearinghouse but a client of a clearing member is also potentially

exposed to a default of the CCP. The exposure depends on the segregation of collateral the client posts to the clearing

member. There are three types of segregation in practice:

Case 1. In this framework, most commonly used in the U.S. and the EU, the collateral posted by the client to its

clearing member is legally segregated from that of the clearing member on its "house (or "proprietary") positions, but is

operationally commingled with the collateral posted by other customers of that clearing member. This is the so-called

Legal Segregation Operational Commingling (LSOC) model. In this case, the collateral posted by the client is

bankruptcy-remote from a default of the clearing member, but not from a joint default of the clearing member and any

WWW.STANDARDANDPOORS.COM/RATINGSDIRECT JUNE 5, 2014 5

1328907 | 300051529

Clearinghouses Are Raising Their Game--But They Are Not Risk-Free

of its other customers. Customers could be subject to pro-rata distribution of assets in the event that another customer

defaults and causes the clearing member to default as well. Over and above a direct exposure to the CCP, the client

bears an additional risk so that bank regulators apply a higher risk weight (4 %) than the 2% pertaining to clearing

members.

As part of the Dodd-Frank Act, the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) published new regulations

to reduce "fellow customer" risk in the clearing of OTC swaps by requiring the LSOC model of collateral segregation.

EMIR also provides for LSOC-type arrangements as a minimum requirement for CCPs. Underlying customers can also

opt for individually segregated accounts if they wish to avoid commingling not only with the member but also the

member's other customers. This corresponds to Case 2, below.

Case 2. In this framework, the collateral posted by the client is individually segregated not only from the collateral

posted by the clearing member on its "house" positions, but also from the collateral posted by other end-customers of

the clearing member. Thus, the client is bankruptcy-remote from the joint default of the clearing member and any of its

other customers. He is seen as having a direct exposure to the CCP, and regulators apply the same 2% risk weight as

that pertaining to exposures of clearing members of qualified CCPs. EMIR regulation makes it compulsory for clearing

houses in the EU to offer such individually segregated accounts services. Clearing members are free to opt for this (and

to propose the services to their individual clients, which, in turn, may go for it or not), or to keep the LSOC model.

Case 3: If the collateral posted by the client is not bankruptcy-remote from the default of the clearing member, so that

its collateral is "commingled" with the collateral posted by the clearing member on its "house" positions, the client is

not seen as having a direct exposure to the CCP, but rather as having a bilateral exposure to the clearing member.

New Regulation Has Strengthened The Quality Of Financial Safeguards

Major CCPs are now generally in a good position to meet the new responsibilities that have been handed to them by

regulators, in our view. We believe that clearinghouses in the EU and in the U.S. in particular have stepped up their

financial safeguards recently--largely thanks to stricter regulation--to minimize losses of non-defaulting clearing

members and ensure market continuity in the case of a member default. For instance, CCPs have generally increased

the resources they make available to absorb clearing risk losses by injecting more of their own capital (or "skin in the

game") within the payment waterfall. We consider substantial "skin in the game" within the waterfall to be a positive

feature because it aligns the interests of the CCP with the interests of its members. With a substantial part of its own

capital at risk, the CCP has an incentive to maintain the robustness of the financial safeguards, which eventually benefit

its members. However, we view too much "skin in the game" in relation of the CCP's total resources as potentially

impairing the CCP's own creditworthiness.

Likewise, in many cases, but not always, guaranty funds now provide CCPs with enough resources to cover losses

arising from the simultaneous default of their largest two clearing members' families under extreme--but

plausible--market conditions (known as "cover 2"). This is required under the new EMIR regulation to be implemented

in the EU next year. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the EMIR reauthorization process being pursued by EU

clearinghouses is also leading to heightened regulatory scrutiny. What's more, these toughened EU and U.S. standards

are in effect being exported because CCPs outside these regions are also having to review and, on occasion, improve

their financial safeguards if they want to be treated as equivalent (i.e., to allow them to be treated by EU/U.S. members

as "qualified" CCPs).

WWW.STANDARDANDPOORS.COM/RATINGSDIRECT JUNE 5, 2014 6

1328907 | 300051529

Clearinghouses Are Raising Their Game--But They Are Not Risk-Free

We believe that differentiation between the robustness of CCPs' financial safeguards could increase in the years to

come because they are increasingly competing with each other for business--in particular to capture the new market of

clearing OTC transactions. Some CCPs may be tempted to relax financial safeguards (for example, by lowering

margins and guaranty fund contributions) to attract customers. Therefore, in our ratings, we analyze the key

differences between CCPs' financial safeguards, particularly with respect to their margining assumptions and guaranty

fund calculations. Generally, CCPs' margining methodology assumes two or three days to liquidate plain vanilla

instruments, such as equity and exchange-traded derivatives, and five days for OTC derivatives. The number of days is

determined by the depth and breadth of the liquidity in the market under stressed scenarios. A CCP's margining level is

determined by both the number of days of coverage (needed to liquidate a position) and the confidence interval

associated with the data used to calculate the margin. Some CCPs, notably in Europe, also provide members with

margin relief for positions that they view as highly correlated. However, there is a risk that the correlations the CCPs

use for margin relief prove wrong when markets stumble and liquidity dries up.

The choices that a CCP makes regarding margining assumptions and guaranty fund calculations give us an indication

of a CCP's risk appetite. For example, assuming a one-day period for liquidating treasury futures may be appropriate in

computing margins in the U.S. given the liquidity of the U.S. market. But it is too lenient, in our view, in most other

markets. Likewise, we take the view that a CCP is more vulnerable to market stress when its guaranty fund's size

covers only the largest clearing member as opposed to the two largest clearing members. Nevertheless, we consider it

positive if a CCP has the right to request their clearing members to replenish the guaranty fund after an event of

default. These assessment powers ensure market continuity, in our view. What matters most in our analysis is the total

resources available to a CCP to cover clearing risk (margins, "skin in the game," guaranty funds, assessment powers)

rather the robustness of any individual components taken in isolation. For example, a best-in-class margining system

may be insufficient if the other resources available to absorb clearing losses are poorly calibrated. For that reason,

assessing the robustness and quality of a clearinghouse's financial safeguards, with an eye to whether business

considerations will tempt them to lower their standards, will remain an essential part of our credit analysis.

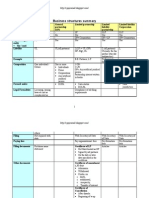

Table 1

Clearinghouses Rated By Standard & Poor's

Long-term corporate credit rating Country of operation

SIX Group AG AA- Switzerland

Deutsche Boerse AG AA Germany

NASDAQ OMX Clearing AB A+ Sweden

CME Group Inc. AA- U.S.

LCH.Clearnet Group Ltd. A+ U.K.

IntercontinentalExchange Group Inc. A U.S.

Fixed Income Clearing Corp. AA+ U.S.

Options Clearing Corp. AA+ U.S.

Asigna Compensacion y Liquidacion BBB+ Mexico

BM&FBOVESPA S.A-Bolsa de Valores, Mercadorias e Futuros BBB+ Brazil

Argentina Clearing S.A. raBB+ Argentina

ASX Clear (Futures) Pty Ltd. AA- Australia

National Securities Clearing Corporation AA+ U.S.

WWW.STANDARDANDPOORS.COM/RATINGSDIRECT JUNE 5, 2014 7

1328907 | 300051529

Clearinghouses Are Raising Their Game--But They Are Not Risk-Free

Table 1

Clearinghouses Rated By Standard & Poor's (cont.)

ra--Argentina national scale rating.

Under Standard & Poor's policies, only a Rating Committee can determine a Credit Rating Action (including a Credit

Rating change, affirmation or withdrawal, Rating Outlook change, or CreditWatch action). This commentary and its

subject matter have not been the subject of Rating Committee action and should not be interpreted as a change to, or

affirmation of, a Credit Rating or Rating Outlook.

Additional Contact:

Financial Institutions Ratings Europe; FIG_Europe@standardandpoors.com

WWW.STANDARDANDPOORS.COM/RATINGSDIRECT JUNE 5, 2014 8

1328907 | 300051529

Clearinghouses Are Raising Their Game--But They Are Not Risk-Free

S&P may receive compensation for its ratings and certain analyses, normally from issuers or underwriters of securities or from obligors. S&P

reserves the right to disseminate its opinions and analyses. S&P's public ratings and analyses are made available on its Web sites,

www.standardandpoors.com (free of charge), and www.ratingsdirect.com and www.globalcreditportal.com (subscription) and www.spcapitaliq.com

(subscription) and may be distributed through other means, including via S&P publications and third-party redistributors. Additional information

about our ratings fees is available at www.standardandpoors.com/usratingsfees.

S&P keeps certain activities of its business units separate from each other in order to preserve the independence and objectivity of their respective

activities. As a result, certain business units of S&P may have information that is not available to other S&P business units. S&P has established

policies and procedures to maintain the confidentiality of certain nonpublic information received in connection with each analytical process.

To the extent that regulatory authorities allow a rating agency to acknowledge in one jurisdiction a rating issued in another jurisdiction for certain

regulatory purposes, S&P reserves the right to assign, withdraw, or suspend such acknowledgement at any time and in its sole discretion. S&P

Parties disclaim any duty whatsoever arising out of the assignment, withdrawal, or suspension of an acknowledgment as well as any liability for any

damage alleged to have been suffered on account thereof.

Credit-related and other analyses, including ratings, and statements in the Content are statements of opinion as of the date they are expressed and

not statements of fact. S&P's opinions, analyses, and rating acknowledgment decisions (described below) are not recommendations to purchase,

hold, or sell any securities or to make any investment decisions, and do not address the suitability of any security. S&P assumes no obligation to

update the Content following publication in any form or format. The Content should not be relied on and is not a substitute for the skill, judgment

and experience of the user, its management, employees, advisors and/or clients when making investment and other business decisions. S&P does

not act as a fiduciary or an investment advisor except where registered as such. While S&P has obtained information from sources it believes to be

reliable, S&P does not perform an audit and undertakes no duty of due diligence or independent verification of any information it receives.

No content (including ratings, credit-related analyses and data, valuations, model, software or other application or output therefrom) or any part

thereof (Content) may be modified, reverse engineered, reproduced or distributed in any form by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval

system, without the prior written permission of Standard & Poor's Financial Services LLC or its affiliates (collectively, S&P). The Content shall not be

used for any unlawful or unauthorized purposes. S&P and any third-party providers, as well as their directors, officers, shareholders, employees or

agents (collectively S&P Parties) do not guarantee the accuracy, completeness, timeliness or availability of the Content. S&P Parties are not

responsible for any errors or omissions (negligent or otherwise), regardless of the cause, for the results obtained from the use of the Content, or for

the security or maintenance of any data input by the user. The Content is provided on an "as is" basis. S&P PARTIES DISCLAIM ANY AND ALL

EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTIES, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, ANY WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR

A PARTICULAR PURPOSE OR USE, FREEDOM FROM BUGS, SOFTWARE ERRORS OR DEFECTS, THAT THE CONTENT'S FUNCTIONING

WILL BE UNINTERRUPTED, OR THAT THE CONTENT WILL OPERATE WITH ANY SOFTWARE OR HARDWARE CONFIGURATION. In no

event shall S&P Parties be liable to any party for any direct, indirect, incidental, exemplary, compensatory, punitive, special or consequential

damages, costs, expenses, legal fees, or losses (including, without limitation, lost income or lost profits and opportunity costs or losses caused by

negligence) in connection with any use of the Content even if advised of the possibility of such damages.

Copyright 2014 Standard & Poor's Financial Services LLC, a part of McGraw Hill Financial. All rights reserved.

WWW.STANDARDANDPOORS.COM/RATINGSDIRECT JUNE 5, 2014 9

1328907 | 300051529

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (120)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Advacc 1001-1014Documento15 pagineAdvacc 1001-1014Camille SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Catastrophic Risk and The Capital Markets: Berkshire Hathaway and Warren Buffett's Success Volatility Pumping Cat ReinsuranceDocumento15 pagineCatastrophic Risk and The Capital Markets: Berkshire Hathaway and Warren Buffett's Success Volatility Pumping Cat ReinsuranceAlex VartanNessuna valutazione finora

- Fundamental AnalysisDocumento7 pagineFundamental AnalysisJyothi Kruthi PanduriNessuna valutazione finora

- Business Plan Bolt & Nuts - Financial AspectsDocumento14 pagineBusiness Plan Bolt & Nuts - Financial AspectsgboobalanNessuna valutazione finora

- Aecom ME Handbook 2014Documento90 pagineAecom ME Handbook 2014Le'Novo FernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- Business AnalystDocumento17 pagineBusiness Analystaabid_chem3363Nessuna valutazione finora

- ACCT 221-Corporate Financial Reporting-Atifa Dar-Waqar AliDocumento6 pagineACCT 221-Corporate Financial Reporting-Atifa Dar-Waqar AliDanyalSamiNessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento13 pagineUntitledapi-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- Investing in Infrastructure: Are Insurers Ready To Fill The Funding Gap?Documento16 pagineInvesting in Infrastructure: Are Insurers Ready To Fill The Funding Gap?api-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- Euro Money Market Funds Are Likely To Remain Resilient, Despite The ECB's Subzero Deposit RateDocumento7 pagineEuro Money Market Funds Are Likely To Remain Resilient, Despite The ECB's Subzero Deposit Rateapi-231665846Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Strong Shekel and A Weak Construction Sector Are Holding Back Israel's EconomyDocumento10 pagineA Strong Shekel and A Weak Construction Sector Are Holding Back Israel's Economyapi-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento21 pagineUntitledapi-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- Outlook On Slovenia Revised To Negative On Policy Uncertainty Ratings Affirmed at 'A-/A-2'Documento9 pagineOutlook On Slovenia Revised To Negative On Policy Uncertainty Ratings Affirmed at 'A-/A-2'api-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento7 pagineUntitledapi-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento9 pagineUntitledapi-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- Islamic Finance Slowly Unfolds in Kazakhstan: Credit FAQDocumento6 pagineIslamic Finance Slowly Unfolds in Kazakhstan: Credit FAQapi-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- Standard & Poor's Perspective On Gazprom's Gas Contract With CNPC and Its Implications For Russia and ChinaDocumento8 pagineStandard & Poor's Perspective On Gazprom's Gas Contract With CNPC and Its Implications For Russia and Chinaapi-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ireland Upgraded To 'A-' On Improved Domestic Prospects Outlook PositiveDocumento9 pagineIreland Upgraded To 'A-' On Improved Domestic Prospects Outlook Positiveapi-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- Romania Upgraded To 'BBB-/A-3' On Pace of External Adjustments Outlook StableDocumento7 pagineRomania Upgraded To 'BBB-/A-3' On Pace of External Adjustments Outlook Stableapi-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento7 pagineUntitledapi-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- Spanish RMBS Index Report Q1 2014: Collateral Performance Continues To Deteriorate Despite Signs of Economic RecoveryDocumento41 pagineSpanish RMBS Index Report Q1 2014: Collateral Performance Continues To Deteriorate Despite Signs of Economic Recoveryapi-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento53 pagineUntitledapi-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- Private BanksDocumento11 paginePrivate BanksCecabankNessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento7 pagineUntitledapi-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento11 pagineUntitledapi-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- What's Holding Back European Securitization Issuance?: Structured FinanceDocumento9 pagineWhat's Holding Back European Securitization Issuance?: Structured Financeapi-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- Latvia Long-Term Rating Raised To 'A-' On Strong Growth and Fiscal Performance Outlook StableDocumento8 pagineLatvia Long-Term Rating Raised To 'A-' On Strong Growth and Fiscal Performance Outlook Stableapi-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento14 pagineUntitledapi-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento9 pagineUntitledapi-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento8 pagineUntitledapi-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento25 pagineUntitledapi-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento14 pagineUntitledapi-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento14 pagineUntitledapi-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento8 pagineUntitledapi-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- Outlook On Portugal Revised To Stable From Negative On Economic and Fiscal Stabilization 'BB/B' Ratings AffirmedDocumento9 pagineOutlook On Portugal Revised To Stable From Negative On Economic and Fiscal Stabilization 'BB/B' Ratings Affirmedapi-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento7 pagineUntitledapi-228714775Nessuna valutazione finora

- Topic 9 - The Standard Capital Asset Pricing Model Answer PDFDocumento20 pagineTopic 9 - The Standard Capital Asset Pricing Model Answer PDFSrinivasa Reddy S100% (1)

- Lecture 1 (Ch4) - NCBA&EDocumento182 pagineLecture 1 (Ch4) - NCBA&EdeebuttNessuna valutazione finora

- Practical Accounting 2: 2011 National Cpa Mock Board ExaminationDocumento6 paginePractical Accounting 2: 2011 National Cpa Mock Board ExaminationMary Queen Ramos-UmoquitNessuna valutazione finora

- Theoretical FrameworkDocumento3 pagineTheoretical Frameworkm_ihamNessuna valutazione finora

- Business Structures SummaryDocumento5 pagineBusiness Structures SummaryMrudula V.100% (2)

- Tamil Nadu Micro Fin Ace ListDocumento7 pagineTamil Nadu Micro Fin Ace Listsachin11jainNessuna valutazione finora

- Uniform Format of Accounts - SummaryDocumento8 pagineUniform Format of Accounts - SummaryGotta Patti House100% (1)

- Working Capital DaburDocumento86 pagineWorking Capital DaburprateekNessuna valutazione finora

- The Future of Securities Regulation PDFDocumento36 pagineThe Future of Securities Regulation PDFRega EidyaNessuna valutazione finora

- ABRAHAM ADESANYA POLYTECHNI2 Mr. OlabamijiDocumento12 pagineABRAHAM ADESANYA POLYTECHNI2 Mr. OlabamijiRasheed Onabanjo DamilolaNessuna valutazione finora

- Financial Accounting Chapter 7Documento57 pagineFinancial Accounting Chapter 7Waqas MazharNessuna valutazione finora

- History and Evolution of Accounting Practices and StandardsDocumento22 pagineHistory and Evolution of Accounting Practices and StandardsmelanawitNessuna valutazione finora

- The Size of The Tradable and Non-Tradable Sector - Evidence From Input-Output Tables For 25 CountriesDocumento15 pagineThe Size of The Tradable and Non-Tradable Sector - Evidence From Input-Output Tables For 25 CountrieskeyyongparkNessuna valutazione finora

- CarlsbergDocumento11 pagineCarlsbergThayaa BaranNessuna valutazione finora

- Securities Listing by Laws 2053Documento14 pagineSecurities Listing by Laws 2053Krishna GiriNessuna valutazione finora

- Manulife Asian Small Cap Equity Fund MASCEF - 201908 - EN PDFDocumento2 pagineManulife Asian Small Cap Equity Fund MASCEF - 201908 - EN PDFHetanshNessuna valutazione finora

- FIN352 FALL17Exam2Documento6 pagineFIN352 FALL17Exam2Hiếu Nguyễn Minh Hoàng0% (1)

- Portersfiveforcestrategy 131215101901 Phpapp01Documento9 paginePortersfiveforcestrategy 131215101901 Phpapp01Ahmed Jan DahriNessuna valutazione finora

- IFRS 17 Is Coming, Are You Prepared For It?: The Wait Is Nearly Over?Documento6 pagineIFRS 17 Is Coming, Are You Prepared For It?: The Wait Is Nearly Over?الخليفة دجوNessuna valutazione finora

- ATW108 Chapter 24 TutorialDocumento1 paginaATW108 Chapter 24 TutorialShuhada ShamsuddinNessuna valutazione finora

- 2019 Level III Errata PDFDocumento4 pagine2019 Level III Errata PDFlinhatranNessuna valutazione finora

- ChallanDocumento2 pagineChallanrchowdhury_10Nessuna valutazione finora

- Wholesale Banking Operation HDFCDocumento43 pagineWholesale Banking Operation HDFCAnonymous H1RRjZmhzNessuna valutazione finora