Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Aristotle On Poetry and Limitation PDF

Caricato da

কিশলয়0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

623 visualizzazioni19 paginePoetics Analysis

Titolo originale

Aristotle On Poetry And Limitation.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoPoetics Analysis

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

623 visualizzazioni19 pagineAristotle On Poetry and Limitation PDF

Caricato da

কিশলয়Poetics Analysis

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 19

1

ARISTOTLE ON POETRY AND IMITATION

In the opening sentence of the Poetics, Aristotle tells us that he is going to deal with

poetry itself, its kinds and their powers, and so on. He then turns to a discussion of

imitation or representation (mi /mhsi j ). Thereafter the treatise is an examination of

imitation in general and in certain of its forms, namely tragedy and epic. We are thus

given to believe that, for Aristotle, poetry is imitation, or that this is his answer to the

question what is poetry?, and is meant to serve as a definition. This is indeed what

scholars have thought.

1

Of course one needs to add the qualifications Aristotle suggests

to distinguish poetry from painting, music and dancing which are also imitation. Poetry

imitates using language (l o/goj ) and rhythm (r(uqmo/j ), and (usually) also harmony or

song (a(rmoni /a, me/l oj ). Use of language will distinguish poetry from dancing and music,

and use of rhythm, or generally verse, will distinguish it from prose imitations like

Socratic dialogues.

That this definition of poetry as imitation is an acceptable one has been held by

many commentators. They have thought that imitation can very easily be applied to all

kinds of poetry and to the fine arts as well. But that this is at best problematic can be seen

if one considers, on the one hand, attempts to do this, and, on the other, Aristotles actual

use of the term imitation.

1

Ingemar Dring, Aristoteles: Darstellung und Interpretation seines Denkens (Winter, Heidelberg, 1966),

p.164; D.W. Lucas, Aristotles Poetics (Clarendon Press, 1968), p. 53, note ad 47a8.

2

P. SOMVILLE in his Essai sur la Potique dAristote

2

finds in imitation a

meaning like stylisation. Imitation does not merely mean the copying of a thing, but the

creating or refracting of it; it involves the taking up of things given in nature, in the real,

and a transformation of them into something other by the creative genius of the artist.

Le produit mimtique estun mixte issu de la perception de certains lments de

ralit et indissociablement de la rfraction de ces lments, proportionelle au

faonnement et linvention de lartiste. (p.51)

SOMVILLE calls on passages in the Politics in support of this, but he refers in particular

to that passage in the Poetics

3

where Aristotle talks of the pleasure involved in

recognizing, in a painting, the image of something real, even when that something is, in

itself, repellent or painful.

Cardinal NEWMAN in his Poetry with Reference to Aristotles Poetics

4

also sees

in imitation a transformation or stylization of the real, but he uses the word ideal to

express this and refers, not to the passage cited by SOMVILLE, but to the comparison of

poetry with history in chapter 9.

Poetry, according to Aristotle, is a representation of the ideal. Biography and

history represent individual characters and actual facts; poetry, on the contrary,

generalizing from the phenomena of nature and life, supplies us with pictures

2

J . Vrin, Paris, 1975, pp. 43-54.

3

ch.4, 1448b16-19.

4

In Aristotle's Poetics and English Literature. A Collection of Critical Essays, Elder Olson, ed. (University

of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1965).

3

drawn, not after an existing pattern, but after a creation of the mind It delineates

that perfection which the imagination suggests, and to which as a limit the present

system of Divine Providence actually tends. (p.88)

Garry HAGBERG and Leon GOLDEN have recently offered other interpretations.

5

HAGBERG argues that imitation means representing the abstract relations between

things, and GOLDEN that it means a learning process, or a mechanism for the

apprehension of truth, that culminates in intellectual clarification (what he says is

meant by ka/qarsi j ). All these commentators try to show how their interpretations of

imitation have a universal application, either to all the fine arts, not just poetry, or to all

kinds of poetry.

However there is plenty of evidence to show that in the Poetics imitation cannot

mean any of these, even though it may involve them. It is applied exclusively to the

imitation of actions. In chapter 2, which is the one that deals with the division of

imitations with respect to the objects imitated, we find that these are limited to people in

action (pra/ttontaj ).

6

This remark is preceded by a since (e)pei /) as if it were an

evident and acknowledged fact. This evident fact is used both here in chapter 2 to divide

the objects imitated into their kinds, and in chapters 4 and 5 to account for the rise of the

different types of poetry. In chapter 9, it is said that the poet should be a poet of stories

(mu=qoi ) rather than of verses (me/tra), since a poet is a poet because of imitation, and

5

Hagberg, Aristotle's Mimesis and Abstract Art, Philosophy 59 (1984): 365-371; Golden, Mimesis and

Katharsis. Classical Philology 64 (1969): 145-153; Toward a Definition of Tragedy, Classical Journal

72 (1976-7): 21-33; Aristotle on Comedy, Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 42 (1983-4): 283-290.

6

1448a1.

4

what is imitated is actions (pra/cei j ).

7

The importance of mu=qoi for Aristotle comes out,

in fact, in the very first sentence, where, in listing the things his treatise on poetry is to

deal with, he expressly mentions how the stories (mu=qoi ) must be put together if the

poem is to be done well, thereby implying that this is one of the integral parts of poetry

as such. The concentration on imitation as an imitation of actions is revealed also by the

fact that only those kinds of poetry are mentioned or dealt with in detail that concern

some story, some telling of an action. This also appears in the case of music, for a passing

remark in chapter 26

8

shows that when Aristotle mentions flute-playing in chapter 1 and

classes it as imitation, what he has in mind is the flute-playing of musicians who imitate

beings in action, discuss-throwers and Scylla, and who resort to vulgar additions to make

their imitation more obvious.

Other remarks that are less explicit seem nevertheless to fit the same pattern.

When Aristotle gives examples of the things painful in themselves but pleasant to see

when painted, he mentions wild beasts and corpses, and this suggests that he had in mind

scenes of hunts and battles (both actions), such as we find in surviving vase-paintings.

Again children are said to learn by imitation,

9

and children typically imitate by doing

what they see adults and other children do. Finally when dancers are said to imitate

characters as well as sufferings and actions, characters seem to be introduced here in the

same way as they are in tragedy, namely for the sake of, and as subservient to, the

action.

10

7

1451b27-9.

8

1461b29-32.

9

ch.4, 1448b5-8.

10

ch.1, 1447a28; ch.6, 1450a20-22.

5

These references are clear enough, yet I am not the first to argue that they show

that imitation in the Poetics means imitation of action. This was done in the last

century by T. TWINING in an essay included in the collection by OLSON.

11

But if

imitation is confined in this way, can it be extended to cover the whole range of fine art

and poetry in general? Is not this range broader than that covered by plot or story or

imitation of action? It is noteworthy that SOMVILLE, NEWMAN, HAGBERG and

GOLDEN only succeed in making imitation cover the whole of poetry or the fine arts

generally by omitting any reference to actions. For while it may be true that imitation

(even the imitation of an action) involves a stylizing and idealizing and a concentration

on abstract relations as well as a learning, to make these the core of its meaning is to use

imitation in a way in which it is not used by Aristotle. For him the connection with

actions is always present.

S. BUTCHER was aware of this point. He agreed that imitation for Aristotle is of

actions, but he also argued that the word actions must have a very broad sense as it is

used in the Poetics.

An act viewed merely as an external process or result, one of a series of outward

phenomena, is not the true object of aesthetic imitation. The pra=ci j that art seeks

to reproduce is mainly an inward process, a psychical energy working outwards;

everything that expresses the mental life, that reveals a rational personality, will

fall within this larger sense of action. The common originalfrom which all

the arts draw is human life, its mental processes, its spiritual movements, its

11

op.cit. pp.42-75, especially p.60.

6

outward acts issuing from deeper sources; in a word, all that constitutes the

inward and essential activity of soul.

12

One consequence of this, as BUTCHER himself points out, is that animals and

landscapes or natural scenes cannot be objects of imitation. The explanation he offers for

this is that Aristotle, following the practice of Greek poets and artists of the classical

period, allows the introduction of the external world only so far as it forms a background

of action, and enters as an emotional element into mans life and heightens the human

interest.

13

All this may be true up to a point, but it cannot be simply correct. It is evident that

for Aristotle actions, in the sense of plots and stories, are the primary or central object of

imitation. Habits and emotions (or the inward activity of soul) are only introduced for

the sake of the action or the story.

14

This would mean that, at least abstract forms of art,

whether statuary, paintings or poetry, would not count as imitations for Aristotle

(contrary to the argument, for instance, of HAGBERG and SOMVILLE). It would also

mean that in those kinds of poetry that seem to concentrate on habits and emotions, or

that are mainly descriptions of states of mind, there would still have to be a reference to

action and this reference would have to be somehow central if such poetry was to count

as imitation in Aristotles sense. But this would be a forced and unnatural position to

adopt.

12

S.H. Butcher, Aristotle's Theory of Poetry and Fine Art, with a Critical Text and a Translation of the

Poetics, 4th. ed., (Dover Publications, 1951), pp.123-4.

13

Ibid.

14

ch.1, 1447a28; ch.6, 1450a20-22.

7

LUCAS hints at an alternative explanation. The reason that Aristotle confined

himself to the four kinds of poetry mentioned in chapter 1, and which are all imitation of

actions, is that they were the most important at the time, either because they were still

being composed or because, in the case of epic, one of its past exponents, Homer,

remained so dominant.

15

But this, even if true, is irrelevant, for anyone who undertook to

examine poetry generally would have to consider all the forms generally known to give a

complete account of the phenomenon. And of course one of these forms was Greek lyric.

Now one might say that Greek lyric poetry is as much an imitation of actions as epic or

tragedy, unlike the sort of lyric poetry that we have become familiar with. But while

some lyric poetry is an imitation of action, not all of it is.

16

Besides it is clearly not the

case that to write poetry one must write about actions. Even if all extant poetry in

Aristotles day was imitation of actions, it is hard to believe that the possibility of there

being other kinds would have entirely escaped his fertile and inquisitive mind.

It would seem from all this that we are reduced to saying either that Aristotle

never intended to write about all poetry, or that if he did he took a far too narrow focus.

Or is there any other possibility left that might do a better job of explaining Aristotles

remarks? I think there is, but it requires one to indulge in a fair amount of speculation.

This is something that is always risky but, in the case of such a puzzling and fragmented

text as the Poetics, it is perhaps more necessary and therefore more excusable than

elsewhere in the Aristotelian corpus. Briefly, what I shall argue is that actions and the

imitation of actions are somehow primary for all poetry, not just dramatic and narrative

kinds. Primary, however, not in the sense of being what all kinds of poetry necessarily

15

op.cit., p.54 note ad 47a13; there is a good discussion of mi /mhsi j in appendix I, pp.258-272.

16

One might take some of the poems of Sappho (e.g. no.31, Bergk's numbering), or some of the choral

odes in surviving tragedies.

8

must aim at and put first, but in the sense that the kind of poetry that does aim at action

and put it first is somehow the first or highest kind of poetry. This is why Aristotle gives

a decided preference to such poetry and treats it as somehow indicative of poetry as such,

because it is indicative of poetry at its best.

17

The suggestion I am making is not without precedent in Aristotles work. In

books Z and H of the Metaphysics Aristotle takes up the subject of being as divided

through the ten categories. He does not deal with all ten, but only the first, substance,

because he regards substance as holding a privileged position among them such that

knowledge of it leads to knowledge of the rest.

18

One finds something similar to this in

the Poetics itself. Such a position of privilege as substance holds over the other categories

is held by tragedy over epic, and in general by tragedy and comedy over the other kinds

Aristotle mentions. From the first five chapters it becomes clear that comedy and tragedy

represent two peaks of development. They are imitation, first of all, in all three means,

not in one or two, as are music, dancing, epic and Socratic dialogues. Secondly they are

at a greater stage of advancement than other poetry that uses all three means, as

dithyrambs, nomes and satyr plays. Chapters 4 and 5 present us with a historical

development from lower to higher, from incomplete to complete, with tragedy and

comedy at the respective ends of two diverging lines, for their forms (sxh/mata) are

greater and held in more honor (mei /zona kai \e)nti mo/tera).

19

This appears more clearly

17

A similar view is put into the mouth of Stephen Dedalus in J ames J oyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a

Young Man (Definitive Text, New York, 1964), pp.214-215. J oyce clearly knew his Aristotle, but the

reasons Dedalus gives for the superiority of dramatic poetry are not those I here attribute to Aristotle.

Dedalus also says that literature is the highest art, and while Aristotle may also have believed that, there is

no evidence that he did. Of course there is the further question in Joyce's case of how far he intended these

remarks of Dedalus to be taken seriouslya question I will not attempt to answer.

18

Metaphysics Z, ch.1.

19

14449a5-6.

9

in the case of tragedy and epic in particular. The more like tragedy epic is the better it is

as epic,

20

and Homer is the best epic poet because he is the most dramatic.

21

Tragedy is

to be treated before epic, because it contains epic but not vice versa, so that to know the

former is also to know the latter.

22

That tragedy and comedy are thus last in time but first

in perfection, and contain the other kinds as the complete contains the incomplete,

explains another puzzle in the Poetics, namely why Aristotle does not deal, nor propose

to deal, even with all the kinds of poetry he does mention in the opening chapters (he

does not say anywhere that he is going to deal with dithyrambs, nomes and satyr plays).

This relationship of perfect and imperfect is shown most clearly between tragedy

and epic. Aristotle says that tragedy is superior to epic because of function: tragedy

achieves this better than epic does.

23

I assume that the function of tragedy and epic is the

same, because although Aristotle does not expressly say what the function of epic is, he

does say what the function of tragedy is and that epic is contained in tragedy. I take this

to mean that what is omitted in the discussion of epic is to be supplied from what is said

of tragedy (we are given no definition of epic; Aristotle leaves us to construct our own

using the definition of tragedy in chapter 6 as a guide). This is backed up by chapters 23

and 24 where Aristotle says epic plots are to be like tragic ones, which implies the

function is the same since the nature of a tragic plot is determined by the function of

tragedy (chs.13 and 14). In chapter 6 the function of tragedy, and hence also of epic, is

20

chs.23, 24, 26.

21

ch.23, 1459a18-21; ch.4, 1448b35-6.

22

ch.5, 1449b17-20; ch.26, 1462a14-17. Carnes Lord has presented some arguments against the idea that

Aristotle holds tragedy to be superior to epic, or at any rate the epic of Homer, in his 'Aristotle's History of

Poetry', Transactions of the American Philological Association, 104 (1974): 195-229. He focuses, however,

on what Aristotle says in chapter 4, and while his arguments do have a certain plausibility in that context,

Aristotle's own remarks in chapter 26 make it very clear that he does hold tragedy to be superior, even to

Homer.

23

1462b14-15.

10

said, or implied, to be the ka/qarsi j (catharsis) of pity and fear through pity and fear.

24

What precisely is meant by ka/qarsi j need not concern us at present; it will be raised

again later.

25

It is sufficient, for the moment, to note two things: one, it is something

pleasant, for the function of tragedy is also said to be the pleasure proper to it,

26

and it is

an idea frequently expressed in the Poetics that tragedy is and should be pleasurable and

enjoyable;

27

two, it is achieved by the excitation of the emotions of pity and fear. This is

already stated in the definition of tragedy and is used in chapters 13 and 14 when the

excellence of plots is examined, for that is said to be the better tragedy which is the more

pitiable and fearful.

28

Tragedy is superior, then, to epic because of its greater

effectiveness at excitation of the relevant emotions, and the greater concentration of the

pleasure it causes.

29

Might, then, the same be true of poetry in general, that while all have the function

of the pleasurable excitation of the emotions (thereby achieving ka/qarsi j ), nevertheless

those kinds that expressly or primarily imitate actions achieve this function better?

An initial approach to this question is to examine what it is that excites emotions.

This is chiefly their objects, so that one feels fear when presented (either in fact or

imagination) with some fearful object, and so with pity and all the others. All the objects

of the emotions, according to Aristotle, are somehow connected with pleasure and pain

30

24

1449b27-8. Aristotle does not expressly say that ka/qarsi j is the function, but this is clearly implied by

the structure of the definition.

25

I agree with Golden that the meaning of ka/qarsi j has something to do with learning (see the articles

referred to above). But this learning is not exclusively intellectual as he seems to imply. ka/qarsi j also

involves teaching or training the emotions, as I suggest below.

26

ch.26., 1462b12-15.

27

ch.9, 1451b23; ch.13, 1453a35-6; ch.14, 1453b10-13.

28

E.g. especially ch.13, 1452b30-33; ch.14, 1453b3-6.

29

ch.26, 1462a14-17.

30

Rhetoric, bk.2; Ethics, 1105b21-23.

11

so that one may say that each is something that is pleasant or painful in the relevant way.

Fear, for example, is of some really or apparently destructive or painful evil that is about

to befall one.

31

The painful and pleasant are also kinds of bad and good, and the bad and

good are painful and pleasant. But that which is most comprehensively and most

emphatically the good and the pleasant for us is happiness (eu)dai moni /a), and conversely

that which is bad or painful in this way is misery (kakodai moni /a). Happiness and misery

are, however, found in action: it is according to characters that people are of such and

such kind, but they are happy or the reverse in their actions (pra/cei j ).

32

If then

emotions are stirred by the good and bad, the painful and pleasant, then the greatest good

and greatest evil, happiness and misery, would seem fitted to do this in the most powerful

way. As these are found in actions, it would seem to follow that it is by the representation

or imitation of actions that poetry will most excite the emotions, actions in which, as

Aristotle says in chapter 13, the characters are portrayed as happy or miserable or passing

from one to the other.

If this argument is sound it clearly gives the superiority to poetry that imitates

actions. But is it sound? I think not and principally because there is something

unsatisfying about the conclusion. Surely other sorts of poetry can affect the emotions as

much as a well-constructed tragedy, and even in the case of existing tragedies it is often

something other than the action that is especially moving. There is much to agree with in

NEWMAN's criticism of Aristotle for making the excellence of tragedies lie in their

plots. Their poetic charm is found, he says, rather in the exquisite delineation of

31

Rhetoric, 1382a21-22.

32

Poetics, ch.6, 1450a17-20.

12

character, in the expression of sentiment, and in the harmonious and majestic language.

33

There is a sense, though, in which dramatic or narrative poems might be superior

here, for it is difficult to imagine anything but the presentation of an action, performed

before one's eyes, sustaining an emotion over time, and gradually increasing it as the plot

unfolds, keeping one, as is said, 'on the edge of one's seat'. It is difficult, too, to imagine

anything else creating the shudder of fear (f ri /ttei n) or the astonished shock (e/)kpl hci j )

that an action can create with a drastic discovery or sudden reversal of fortune.

34

But this difference is not all that great. It certainly does not seem enough on its

own to justify or explain Aristotle's preference for action-imitating poetry. Something

else about imitation of actions seems to be needed.

At this stage, to pursue my argument further I must appeal beyond the Poetics to

the Politics, and in particular to what Aristotle says in book 8 about music. There are two

points I want specifically to notice, and the first concerns catharsis.

35

Since music has

this in common with poetry in Aristotle's eyes and as his work on poetry is expressly

referred to in the context, one is entitled to consider if the treatment of it here may throw

some light on its place in the Poetics. As an example of the cathartic effect of music,

Aristotle gives religious, orgiastic music, which, he says, restores some people who hear

it as if they had received a cure and catharsis.

36

He adds that this is something universal

and that all will feel the same effect in proportion as they are susceptible to the various

emotions (among which pity and fear are mentioned by name); they will experience a

catharsis and a pleasurable 'relief' or 'easing'. The word used means to lighten, to remove

33

Olson, op.cit., pp.82-4.

34

ch.14, 1453b5; ch.15, 1454a4; ch.16, 1455a16-18.

35

Politics, 1341b32-1342a16.

36

1342a10-11.

13

a load or burden (kouf i /zesqai );

37

we ourselves use this same idea in certain contexts,

for we sometimes say to those who are suffering some grief or sorrow that a good cry

will make them feel better, as if relieving or lightening the load of pain. It would be

wrong to press these comments too far, but they suggest that catharsis is more thorough

where the exercise of emotion is more vigorous and sensational and sustained at a higher

pitch, as in the case of the frenzy caused by orgiastic music.

One can return here to the point just made about the power to excite emotion of

the different kinds of poetry. I suggested that those that imitate actions are superior in

their creating sudden surges of emotion as if by violent impact (I referred to the words

f ri /ttei n and e/)kpl hci j ), and in their sustaining a high pitch of excitement. If, as the

Politics passage suggests, catharsis is connected with the force and the sustaining of the

emotional effect, then action-imitating poetry would be superior in this respect.

One need not object to this that Aristotle would oppose such violent exercise of

emotion because it would be excessive and threaten the mean of virtue. The excessive is

not the too much by way of quantity but the too much by way of not being how, when

and about what it ought to be. Sometimes it may well be that some violent or intense

emotional feeling is the mean, and this is what Aristotle does suggest is true of orgiastic

music when it has a cathartic effect.

The second point I want to notice in the Politics concerns the moral effect of

artistic imitations. But before this is developed some defense is required, for Aristotle's

analysis of poetry in the Poetics ignores almost entirely its moral effect on the audience.

There is no hint of any of Plato's strictures against poetry. When Aristotle talks about

37

1342a14.

14

what the poet should or should not do, this should (dei =) is a thoroughly artistic one; it is

referred wholly to the requirements of the art, to what is required for a tragedy or epic to

be good as a tragedy or epic, not to be good as tending to make people morally better or

worse. Again the division in chapter 2 of the persons portrayed into better, worse and the

same as us, is not used to make any moral prescriptions; on the contrary, the portrayal of

the worse, far from being disapproved, constitutes a distinct and legitimate kind of

poetry, namely comedy, and comedy is, for Aristotle, artistically one of the highest kinds

of poetry. Even in chapter 25 where the criticisms of poetry are discussed, the criticism

on the ground of immorality (that the portrayal may be harmfulbl abera/or not

finemh\kal w=j ) is only upheld if the immorality or depravity (moxqhri /a) cannot be

justified in terms of the needs of the poem.

38

It does not appear from this that, as far as

Aristotle is concerned, it is any part of the task or intention of the poet or poetry to be

morally good.

It is one thing, however, to consider what is required for a poem to be good as a

poem of the appropriate type, and another to consider whether poems of this type,

whether done well or badly, are desirable or good. Or to relate it specifically to the

present topic, it is one thing to ask how a poem can be good at effecting catharsis of the

emotions, and another to ask if such catharsis is good or bad. The first question is an

artistic one, and since the Poetics is a treatise on art, it is confined to such artistic matters.

The second, however, is a moral and political one, and therefore is to be raised and

answered by the science of ethics and politics (and Aristotle does in fact raise and answer

such questions about music in the Politics). There is a parallel here with the Rhetoric.

38

1461a4-9; 1461b19-22.

15

Most of this treatise is concerned with purely artistic questions, how to make such and

such a position plausible; whether some of these methods are reprehensible is not

considered (though some clearly are). However an exception is made in the introductory

chapter 1,

39

where Aristotle does raise the moral questions and defends rhetoric against

criticisms on this score, showing that there is a difference between the art and its use, and

that while it may be wrong to use such methods, it is not wrong but very useful to

speculate on these methods and see how they can be used for wrong ends. But if Aristotle

was ready to speak of moral as well as artistic questions in the case of rhetoric, there can

be no reason to deny that he would be ready to do so also in the case of poetry.

40

It does not follow then that if Aristotle has been silent about the moral worth of

poetry in the Poetics, we must ignore it in asking if it is relevant in assessing the

excellences of different kinds of poetry (just as Aristotle does not in fact ignore it in

assessing the excellences of different kinds of music in the Politics). For it may well be

that with respect to the order and attainment of human goods, and therefore with respect

especially to political life, one kind is higher than another, and it may be because of this

that Aristotle has a preference for it and desires to understand it and set in on a proper

artistic footing, whereas he is less concerned to do this with respect to the other types.

How poetry may be morally beneficial can be seen from what Aristotle says about

music in this respect,

41

namely that listening to it is going to affect one's character, one's

moral habits. One reason given for this is that music is something pleasant and virtue

39

Especially 1355a19-b7; cf. Physics, 184b25-185a20.

40

On this question of the moral significance of poetry I am in broad agreement with Carnes Lord; see his

Education and Culture in the Political Thought of Aristotle (Cornell, Ithaca, 1982), especially chapter four.

His comments on the moral and political concern of the Rhetoric are also pertinent; see his 'The Intention

of Aristotle's Rhetoric', Hermes 109 (1981): 326-339.

41

Politics, 1340a5-14.

16

concerns enjoying, liking and disliking in the right way. So much are the pleasant and

painful bound up with the virtues that it is a sign of virtue to feel pleasure and pain as one

ought; and the right sort of education is one that accustoms one to judge rightly and, from

one's youth, to be pleased by the fine and pained by the base.

42

All poetry will have an

effect on character just like music, for poetry is pleasant and excites the emotions by

presenting the painful and the pleasant, but action-imitating poetry appears to be likely to

do this more beneficially. The reason for this lies in the fact that, unlike the other kinds, it

affects the emotions in the context of an action, of a life or part of a life dramatically

displayed before one's eyes. To feel an emotion consequent on the representation of an

action that contains the object of that emotion, the fearful and pitiable for instance, is not

to feel it simply, but to see, at the same time, those objects in their causes, to see how

they follow, in all likelihood or of necessity, from certain actions that precede them. It is

also, and this is important, to feel the emotion about the causes. In the case of tragedy, for

instance, the causes of things pitiable and fearful are themselves made to appear pitiable

and fearful, for what makes the tragic action, when constructed best, so pitiable and

fearful, is that the fearful and pitiable things are shown arising out of something

unexpected and apparently harmless, and to someone who is like us, neither extremely

bad nor extremely good.

43

The fearfulness of the consequences is thrown back onto the

cause, so that that too becomes fearful, and all the more so the more vividly this is done.

Action-imitating poetry thus has an important teaching function and it will be this

teaching function of dramatic and narrative poetry (wherein, incidentally, the poet is

42

Ethics, 1104b12-13; 1105a10-12; Politics, 134014-18.

43

ch.9, 1452a1-4, ch.13, 1453a5-10.

17

likened to the philosopher)

44

that will be at least part of what is meant by catharsis. This

interpretation of catharsis will, interestingly, allow one to combine different theories

about that much disputed term, namely the intellectual clarification theory and the

purification theory.

45

This is because the teaching that goes on is of two sorts, both

intellectual and emotional. The mind is instructed to recognize what things are truly and

not just apparently fearful or pitiable, and the emotions are likewise instructed, or rather

trained, to be exercised over the truly fearful and pitiable in the same way, and to be

exercised over them to the right amount. Thus the mind is clarified so as to see what

desirable or undesirable effects are likely to follow from what causes, and the emotions

are purified so as to be felt over the things they ought to be felt over, and to the extent

they ought to be felt over them.

46

This, at any rate, will be the effect of good dramatic

and narrative poetry, I mean poetry that is done well and hence that does both display the

causes of things, and powerfully excite the emotions about them as well.

The effectiveness of this way of teaching, of teaching by means of effects and of

the emotions stimulated by those effects, becomes clear from the fact that those things

that really are bad appear to be good because of some pleasure attached to them, and

those things that really are good appear to be bad because of some pain attached to them,

or, to quote Aristotle, we do the base because of pleasure and avoid the fine because of

44

ch.9, 1451b5-6.

45

There are roughly three interpretations of catharsis: purgation, purification and clarification. Purgation is

a medical theory, purification a moral one, and clarification an intellectual one. The first two, despite

differences, are rather close to each other and can be treated as one. All have something to be said for them,

as well as something against. A useful summary and discussion of all of them can be found in K.G.

Srivastava, "A New Look at the 'Katharsis' Clause of Aristotle's Poetics," British Journal of Aesthetics 12

(1972): 258-275. Srivastava himself offers an aesthetic interpretation, which, in view of Aristotle's moral

concern in the Politics, cannot be a complete account, though it may be partially true. Pierre Somville has

followed him in this, though with some qualifications, op.cit., ch.2. Leon Golden is the main proponent of

the clarification theory (see the articles cited above). D.W. Lucas repeats the view of Bernays, which he

regards as both purification and purgation, op. cit., appendix II.

46

Lucas' remarks on the idea of purification as applied to catharsis are to the point here, op.cit., p.279ff.

18

pain.

47

One of the ways, if not the way, of getting around this (since we so instinctively

associate the bad with pain and the good with pleasure) is to learn the badness of what is

bad by seeing the painful consequences it issues in, and to learn the goodness of what is

good by seeing the pleasant or desirable consequences it issues in. We must learn to look

to the end of things. By seeing and being made to feel by an action that such and such

qualities and such and such deeds are, while apparently desirable and good, in reality not

so, one's understanding and emotions are being morally informed.

Both action-imitating and other sorts of poetry will have such an effect but the

first will do so in a more obvious and emphatic way, for it will necessarily have to

present the moral not in words only but in a concrete case, described or acted out before

one's eyes. All of us and especially the 'many' are more impressed by the particular and

concrete.

48

It follows that action-imitating poetry is of considerable value as a tool of

moral education, especially for the many, and the more so the more vivid and emotionally

stirring it is. Since the other kinds, insofar as they really differ from this kind, do not

portray actions and their causal connections, they do not stand so high on the scale. They

may have cathartic effects but not so powerfully nor so informatively; consequently they

will not be as beneficial emotionally or morally.

In these two connected respects then, the force and sustaining of powerful

emotional experiences, and the moral teaching of the mind and the emotions through the

presentation of such emotionally charged actions in their concrete causal relations,

dramatic and narrative poetry will be superior to the other kinds of poetry. This is the

reason, or part of the reason, I maintain, why Aristotle should have preferred them and

47

Ethics, 1104b10-11.

48

Topics, 105a13-18.

19

have devoted a treatise to them under the generic title of poetry while neglecting the other

kinds.

Peter Simpson

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Lyn Hejinian, Charles Bernstein, and Language PoetryDa EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Lyn Hejinian, Charles Bernstein, and Language PoetryNessuna valutazione finora

- Reflections On Bullocky: Longing To Belong: Judith Wright's Poetics of PlaceDocumento3 pagineReflections On Bullocky: Longing To Belong: Judith Wright's Poetics of PlaceSudeeksha LangerNessuna valutazione finora

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Jane Johnston Schoolcraft and American Indian Poetry in the Romantic EraDa EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Jane Johnston Schoolcraft and American Indian Poetry in the Romantic EraNessuna valutazione finora

- Aristotle Poetics Paper PostedDocumento9 pagineAristotle Poetics Paper PostedCurtis Perry OttoNessuna valutazione finora

- Wuthering HeightsDocumento23 pagineWuthering HeightsRw KhNessuna valutazione finora

- Character in If On A Winter's Night A TravelerDocumento6 pagineCharacter in If On A Winter's Night A Travelerdanilo lopez-romanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Passionate Shepherd's Invitation to AdventureDocumento19 pagineThe Passionate Shepherd's Invitation to AdventureMohammad Suleiman AlzeinNessuna valutazione finora

- The Theme of Mortality in The Poem DaddyDocumento5 pagineThe Theme of Mortality in The Poem DaddyAntonia Vocheci100% (1)

- Research Essay Sylvia Plath - Documentos de GoogleDocumento6 pagineResearch Essay Sylvia Plath - Documentos de Googleapi-511771050Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sylvia PlathDocumento6 pagineSylvia Plathedward romeoNessuna valutazione finora

- A Study Guide for Samuel Taylor Coleridge's "Frost at Midnight"Da EverandA Study Guide for Samuel Taylor Coleridge's "Frost at Midnight"Nessuna valutazione finora

- 06 BRichards, Practical CriticismDocumento4 pagine06 BRichards, Practical Criticismjhapte02Nessuna valutazione finora

- Plath's Portrayal of Death in Selected PoemsDocumento10 paginePlath's Portrayal of Death in Selected PoemsRebwar MuhammadNessuna valutazione finora

- Amoretti As Allegory of Love PDFDocumento18 pagineAmoretti As Allegory of Love PDFKaryom NyorakNessuna valutazione finora

- Three YearsDocumento48 pagineThree Yearsiola90Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Study of Coleridges Dejection - An Ode PDFDocumento105 pagineA Study of Coleridges Dejection - An Ode PDFNasir Iqbal100% (1)

- Thomas Wyatt's The Long Love That In My Thought Doth Harbor explores hidden courtly loveDocumento5 pagineThomas Wyatt's The Long Love That In My Thought Doth Harbor explores hidden courtly loverngband11Nessuna valutazione finora

- 08 Poetics of John AshberyDocumento12 pagine08 Poetics of John AshberySudhir ChhetriNessuna valutazione finora

- The Criticism of Nissim EzekielDocumento6 pagineThe Criticism of Nissim EzekielKaushik RayNessuna valutazione finora

- John KeatsDocumento148 pagineJohn KeatsMà Ř YãmNessuna valutazione finora

- Sir Philip Sidney & The Defence of PoesyDocumento45 pagineSir Philip Sidney & The Defence of Poesyaiza aliNessuna valutazione finora

- Did Hamlet Love Ophelia?: and Other Thoughts on the PlayDa EverandDid Hamlet Love Ophelia?: and Other Thoughts on the PlayNessuna valutazione finora

- Northrop FryeDocumento18 pagineNorthrop FryeRaghuramanJNessuna valutazione finora

- tmp9634 TMPDocumento24 paginetmp9634 TMPFrontiersNessuna valutazione finora

- Philip Sidney As A HumanistDocumento3 paginePhilip Sidney As A HumanistSho100% (2)

- Impressionism in Woolf's Orlando and Between the ActsDocumento7 pagineImpressionism in Woolf's Orlando and Between the ActsKittyKeresztesNessuna valutazione finora

- Coleridge's Theory of ImaginationDocumento5 pagineColeridge's Theory of ImaginationSTANLEY RAYENNessuna valutazione finora

- A Study Guide for Wislawa Szymborska's "Conversation with a Stone"Da EverandA Study Guide for Wislawa Szymborska's "Conversation with a Stone"Nessuna valutazione finora

- Character in If On A Winter's Night A TravelerDocumento6 pagineCharacter in If On A Winter's Night A Travelerdanilo lopez-roman0% (1)

- 09 Shelley Defence of PoetryDocumento5 pagine09 Shelley Defence of PoetrysujayreddNessuna valutazione finora

- Jayanta Mahapatra's Dawn at PuriDocumento1 paginaJayanta Mahapatra's Dawn at PuriDr. Hasinus Sultan67% (3)

- Traditional and Indivisual TalentDocumento3 pagineTraditional and Indivisual TalentKhubaib KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Analysis of Sir Philip SidneyDocumento2 pagineAnalysis of Sir Philip SidneyTaibur RahamanNessuna valutazione finora

- Ode To A Nightingale - A Critical AppreciationDocumento3 pagineOde To A Nightingale - A Critical AppreciationHimel IslamNessuna valutazione finora

- Jayanta MahapatraDocumento10 pagineJayanta MahapatrasanamachasNessuna valutazione finora

- Ode To Nightingale by KeatsDocumento4 pagineOde To Nightingale by Keatsmanazar hussainNessuna valutazione finora

- Themes of American PoetryDocumento2 pagineThemes of American PoetryHajra ZahidNessuna valutazione finora

- An Essay on Man, The Rape of the Lock, and Other PoemsDa EverandAn Essay on Man, The Rape of the Lock, and Other PoemsNessuna valutazione finora

- Pablo Neruda - Twenty Love Poems - 1969 PDFDocumento37 paginePablo Neruda - Twenty Love Poems - 1969 PDFRavi KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- The Scarlet LetterDocumento5 pagineThe Scarlet LetterSimina AntonNessuna valutazione finora

- Mersault's Indifference in The StrangerDocumento19 pagineMersault's Indifference in The Strangeriqra khalid100% (1)

- Portrait of The Artist As A Young Man - Excerpts, QuotesDocumento7 paginePortrait of The Artist As A Young Man - Excerpts, QuotesJelena ŽužaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sylvia Plath A Great DepressionDocumento8 pagineSylvia Plath A Great DepressionRuben TabalinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Tiling Work: Checklist 1305Documento2 pagineTiling Work: Checklist 1305কিশলয়Nessuna valutazione finora

- Checklist1401 - Plumbing WorksDocumento3 pagineChecklist1401 - Plumbing Worksকিশলয়Nessuna valutazione finora

- Working at Heights - Training Powerpoint PDFDocumento112 pagineWorking at Heights - Training Powerpoint PDFDwi Yulianto100% (4)

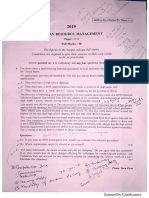

- Scanned by CamscannerDocumento10 pagineScanned by Camscannerকিশলয়Nessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To Information SystemsDocumento118 pagineIntroduction To Information Systemsকিশলয়Nessuna valutazione finora

- IISWBM MBA Evening: Batch 2021-23 Paper C1 - Business Statistics Assignment No. - A1 Submitted by - Kishalay Patra Roll No - 16Documento1 paginaIISWBM MBA Evening: Batch 2021-23 Paper C1 - Business Statistics Assignment No. - A1 Submitted by - Kishalay Patra Roll No - 16কিশলয়Nessuna valutazione finora

- Principles of Management Unit 1 Evolution and ConceptsDocumento308 paginePrinciples of Management Unit 1 Evolution and ConceptsCommerce WhizNessuna valutazione finora

- Checklist1102 - Structural Steelwork - On Site ErectionDocumento1 paginaChecklist1102 - Structural Steelwork - On Site Erectionকিশলয়Nessuna valutazione finora

- Checklist404 - Timber Pile and DrivingDocumento1 paginaChecklist404 - Timber Pile and Drivingকিশলয়Nessuna valutazione finora

- Organizational Behaviour Case Study: Presented By: Name RollDocumento11 pagineOrganizational Behaviour Case Study: Presented By: Name Rollকিশলয়Nessuna valutazione finora

- Organisational Behaviour: Directorate of Distance & Continuing Education Utkal University, Bhubaneswar-7, OdishaDocumento186 pagineOrganisational Behaviour: Directorate of Distance & Continuing Education Utkal University, Bhubaneswar-7, OdishaKrishan Kant MeenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Marketing EnvironmentDocumento48 pagineMarketing Environmentabhishek jainNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Add Hik-Connect Device To Ivms4500 Fna081716 1Documento12 pagineHow To Add Hik-Connect Device To Ivms4500 Fna081716 1Hilmy DarwisyNessuna valutazione finora

- The Marketing EnvironmentDocumento7 pagineThe Marketing EnvironmentMageshNessuna valutazione finora

- Amd 456-2000-2013Documento5 pagineAmd 456-2000-2013Apoorv MahajanNessuna valutazione finora

- Fischer NaanDocumento8 pagineFischer Naanprompt consortiumNessuna valutazione finora

- Hikvision Product Security White PaperDocumento28 pagineHikvision Product Security White PaperEl Kader SurveillanceNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Configure Cloud Storage by Web BrowserDocumento6 pagineHow To Configure Cloud Storage by Web BrowserJoseph Koffivi ADZOHNessuna valutazione finora

- CyberSecurity WhitePaper en PDFDocumento45 pagineCyberSecurity WhitePaper en PDFruben sandovalNessuna valutazione finora

- Is 808 1989Documento20 pagineIs 808 1989713e5db8Nessuna valutazione finora

- IEEE Guide For Substation Fire Protection: IEEE Power and Energy SocietyDocumento13 pagineIEEE Guide For Substation Fire Protection: IEEE Power and Energy SocietyLaura Bibiana Valero PaezNessuna valutazione finora

- Is.15325.2003 0 PDFDocumento42 pagineIs.15325.2003 0 PDFAkhilesh Kag0% (1)

- Sikament FF, Msds310311Documento3 pagineSikament FF, Msds310311কিশলয়100% (1)

- Draft Safety Regulation 2016-2Documento109 pagineDraft Safety Regulation 2016-2Anonymous bxAM8j100% (1)

- IP55 Weatherproof Outdoor Push SwitchDocumento1 paginaIP55 Weatherproof Outdoor Push Switchকিশলয়Nessuna valutazione finora

- OLA Kishalay Patra: Fare Breakup Tax BreakupDocumento2 pagineOLA Kishalay Patra: Fare Breakup Tax Breakupকিশলয়Nessuna valutazione finora

- Government of West Bengal Finance Department Audit BranchDocumento32 pagineGovernment of West Bengal Finance Department Audit BranchSouravDey100% (1)

- Open Quiz - Station Road (Prelims)Documento100 pagineOpen Quiz - Station Road (Prelims)কিশলয়Nessuna valutazione finora

- Nazrul Song LyricsDocumento2 pagineNazrul Song Lyricsকিশলয়Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ola Cabs 187481893Documento1 paginaOla Cabs 187481893কিশলয়Nessuna valutazione finora

- Apcotherm HR FinishDocumento1 paginaApcotherm HR Finishgowtham_venkat_4Nessuna valutazione finora

- Surface Area Practice ProblemsDocumento4 pagineSurface Area Practice ProblemsNoonTeachathanyakulNessuna valutazione finora

- Fashionable Accessories and Their OriginsDocumento12 pagineFashionable Accessories and Their OriginsAdonis GaleosNessuna valutazione finora

- African Flower Soccer BallDocumento4 pagineAfrican Flower Soccer BallMaria Veronica Castillo100% (2)

- Quik Drive Auto Feed Screw Driving Systems Product Catalog 307768 PDFDocumento20 pagineQuik Drive Auto Feed Screw Driving Systems Product Catalog 307768 PDFAnasNessuna valutazione finora

- 2015 Wassce Gka - Paper 2 SolutionDocumento4 pagine2015 Wassce Gka - Paper 2 SolutionKwabena AgyepongNessuna valutazione finora

- Architect Charles GarnierDocumento20 pagineArchitect Charles Garniertanie100% (1)

- Nature Master - User's GuideDocumento28 pagineNature Master - User's GuideseriecancioncoreaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Real Gaze Film Theory After LacanDocumento267 pagineThe Real Gaze Film Theory After LacanCizic Woat100% (14)

- Lucrare de Atestat La Limba EnglezaDocumento34 pagineLucrare de Atestat La Limba EnglezaAlexandraMariaGheorgheNessuna valutazione finora

- Artwork Analysis WorksheetDocumento5 pagineArtwork Analysis WorksheetMary Antonette LoterteNessuna valutazione finora

- IKEA Small Business 2010 Great Britian - EnglishDocumento15 pagineIKEA Small Business 2010 Great Britian - Englishkarisma_bsNessuna valutazione finora

- Chord ProgressionsDocumento6 pagineChord Progressions01hern0% (1)

- Roberto Tejada National Camera Photography and Mexicos Image Environment 2009Documento224 pagineRoberto Tejada National Camera Photography and Mexicos Image Environment 2009baranakkushNessuna valutazione finora

- 2021 Stage Two Visual Art Aboriginal Art Term 1Documento11 pagine2021 Stage Two Visual Art Aboriginal Art Term 1api-578520380Nessuna valutazione finora

- Qcs 2010 Section 13 Part 4 Unit Masonry PDFDocumento12 pagineQcs 2010 Section 13 Part 4 Unit Masonry PDFbryanpastor106100% (1)

- Surface Treatments, Coatings, and CleaningDocumento13 pagineSurface Treatments, Coatings, and CleaningsimalaraviNessuna valutazione finora

- Danielle Culibao: - Twofold (2016), Drawing/painting - The Test of Time (2016), Drawing/paintingDocumento3 pagineDanielle Culibao: - Twofold (2016), Drawing/painting - The Test of Time (2016), Drawing/paintingDanielle CulibaoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Portrait of Zimri From Absalom & Achitophel - John Dryden Absalom & Achitophel (Deep Analysis)Documento7 pagineThe Portrait of Zimri From Absalom & Achitophel - John Dryden Absalom & Achitophel (Deep Analysis)Andrew Eugene100% (6)

- How To Make Adobe Illustrator Metallic Logo Designs in Gold Silver Copper Amp Rose ColorsDocumento12 pagineHow To Make Adobe Illustrator Metallic Logo Designs in Gold Silver Copper Amp Rose Colorshasan tareqNessuna valutazione finora

- 20th Century MusicDocumento5 pagine20th Century MusicEdfeb9Nessuna valutazione finora

- Necro-Utopia - The Politics of Indistinction and The Aesthetics of The Non-Soviet by Alexei YurchakDocumento26 pagineNecro-Utopia - The Politics of Indistinction and The Aesthetics of The Non-Soviet by Alexei Yurchakangryinch100% (1)

- Build Your Own Electric Guitar!Documento29 pagineBuild Your Own Electric Guitar!Jackson Reborn100% (2)

- 50 Short Questions For MerchandisersDocumento8 pagine50 Short Questions For MerchandisersSîronamHin MonirNessuna valutazione finora

- Hans Delbrück - History of The Art of War, Vol 4 - The Dawn of Modern Warfare (1990, University of Nebraska Press) PDFDocumento501 pagineHans Delbrück - History of The Art of War, Vol 4 - The Dawn of Modern Warfare (1990, University of Nebraska Press) PDFMigue Martín100% (3)

- Inkjet Printing ProductsDocumento156 pagineInkjet Printing ProductsglobalsignsNessuna valutazione finora

- GE 06 Research WorkDocumento14 pagineGE 06 Research WorkDion Anthony BaltarNessuna valutazione finora

- Siemens: 1200 MW DGEN Mega Power ProjectDocumento4 pagineSiemens: 1200 MW DGEN Mega Power ProjectJuzer MadarwalaNessuna valutazione finora

- Kiran Nadar Museum of Arts2Documento8 pagineKiran Nadar Museum of Arts2ankitankit yadavNessuna valutazione finora

- Arts Grade 10 Q1 ModuleDocumento44 pagineArts Grade 10 Q1 ModuleMichael Gutierrez dela Pena82% (17)