Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

General Concepts Protozoa

Caricato da

Roshan PMTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

General Concepts Protozoa

Caricato da

Roshan PMCopyright:

Formati disponibili

PROTOZOA

General Concepts

Protozoa

Protozoa are one-celled animals found worldwide in most habitats. Most

species are free living, but all higher animals are infected with one or more species of

protozoa. Infections range from asymptomatic to life threatening, depending on the

species and strain of the parasite and the resistance of the host.

Structure

Protozoa are microscopic unicellular eukaryotes that have a relatively

complex internal structure and carry out complex metabolic activities. Some protozoa

have structures for propulsion or other types of movement.

Classification

On the basis of light and electron microscopic morphology, the protozoa are

currently classified into six phyla. Most species causing human disease are members

of the phyla Sacromastigophora and picomplexa.

ife Cycle Sta!es

!he stages of parasitic protozoa that actively feed and multiply are fre"uently

called trophozoites# in some protozoa, other terms are used for these stages" Cysts

are stages with a protective membrane or thic$ened wall. Protozoan cysts that must

survive outside the host usually have more resistant walls than cysts that form in

tissues.

Reproduction

%inary fission, the most common form of reproduction, is asexual# multiple

asexual division occurs in some forms. %oth sexual and asexual reproduction occur in

the picomplexa.

#utrition

ll parasitic protozoa re"uire preformed organic substancesthat is, nutrition is

holozoic as in higher animals.

1

$#TRO%&CT$O#

!he Protozoa are considered to be a sub$ingdom of the $ingdom Protista,

although in the classical system they were placed in the $ingdom nimalia. More than

'()((( species have been described, most of which are free&living organisms#

protozoa are found in almost every possible habitat. !he fossil record in the form of

shells in sedimentary roc$s shows that protozoa were present in the Pre&cambrian era.

nton van 'eeuwenhoe$ was the first person to see protozoa, using microscopes he

constructed with simple lenses. %etween ()*+ and (*(), he described, in addition to

free&living protozoa, several parasitic species from animals, and Giardia lamblia from

his own stools. ,irtually all humans have protozoa living in or on their body at some

time, and many persons are infected with one or more species throughout their life.

Some species are considered commensals, i.e., normally not harmful, whereas others

are patho!ens and usually produce disease. Protozoan diseases range from very mild

to life&threatening. Individuals whose defenses are able to control but not eliminate a

parasitic infection become carriers and constitute a source of infection for others. In

geographic areas of high prevalence, well&tolerated infections are often not treated to

eradicate the parasite because eradication would lower the individual-s immunity to

the parasite and result in a high li$elihood of reinfection.

Many protozoan infections that are inapparent or mild in normal individuals

can be life&threatening in immunosuppressed patients, particularly patients with

ac"uired immune deficiency syndrome .I/S0. 1vidence suggests that many healthy

persons harbor low numbers of Pneumocystis carinii in their lungs. 2owever, this

parasite produces a fre"uently fatal pneumonia in immunosuppressed patients such as

those with I/S. Toxoplasma gondii, a very common protozoan parasite, usually

causes a rather mild initial illness followed by a long&lasting latent infection. I/S

patients, however, can develop fatal toxoplasmic encephalitis. Cryptosporidium was

described in the (3th century, but widespread human infection has only recently been

2

recognized. Cryptosporidium is another protozoan that can produce serious

complications in patients with I/S. Microsporidiosis in humans was reported in

only a few instances prior to the appearance of I/S. It has now become a more

common infection in I/S patients. s more thorough studies of patients with I/S

are made, it is li$ely that other rare or unusual protozoan infections will be diagnosed.

Acanthamoeba species are free&living amebas that inhabit soil and water. 4yst stages

can be airborne. Serious eye&threatening corneal ulcers due to Acanthamoeba species

are being reported in individuals who use contact lenses. !he parasites presumably are

transmitted in contaminated lens&cleaning solution. mebas of the genus Naegleria,

which inhabit bodies of fresh water, are responsible for almost all cases of the usually

fatal disease primary amebic meningoencephalitis. !he amebas are thought to enter

the body from water that is splashed onto the upper nasal tract during swimming or

diving. 2uman infections of this type were predicted before they were recognized and

reported, based on laboratory studies of canthamoeba infections in cell cultures and

in animals.

!he lac$ of effective vaccines, the paucity of reliable drugs, and other

problems, including difficulties of vector control, prompted the 5orld 2ealth

Organization to target six diseases for increased research and training. !hree of these

were protozoan infectionsmalaria, trypanosomiasis, and leishmaniasis. lthough new

information on these diseases has been gained, most of the problems with control

persist.

Structure

Most parasitic protozoa in humans are less than '( *m in size. !he smallest

.mainly intracellular forms0 are ( to (6 7m long, but Balantidium coli may measure

(86 7m. Protozoa are unicellular eu$aryotes. s in all eu$aryotes, the nucleus is

enclosed in a membrane. In protozoa other than ciliates, the nucleus is vesicular, with

scattered chromatin giving a diffuse appearance to the nucleus, all nuclei in the

individual organism appear ali$e. One type of vesicular nucleus contains a more or

less central body, called an endosome or karyosome. !he endosome lac$s /9 in

the parasitic amebas and trypanosomes. In the phylum picomplexa, on the other

hand, the vesicular nucleus has one or more nucleoli that contain /9. !he ciliates

have both a micronucleus and macronucleus, which appear "uite homogeneous in

composition.

3

!he organelles of protozoa have functions similar to the organs of higher

animals. !he plasma membrane enclosing the cytoplasm also covers the pro+ectin!

locomotory structures such as pseudopodia, cilia, and fla!ella. !he outer surface

layer of some protozoa, termed a pellicle, is sufficiently rigid to maintain a distinctive

shape, as in the trypanosomes and Giardia. 2owever, these organisms can readily

twist and bend when moving through their environment. In most protozoa the

cytoplasm is differentiated into ectoplasm .the outer, transparent layer0 and

endoplasm .the inner layer containing organelles0# the structure of the cytoplasm is

most easily seen in species with pro:ecting pseudopodia, such as the amebas. Some

protozoa have a cytosome or cell ;mouth; for ingesting fluids or solid particles.

4ontractile vacuoles for osmoregulation occur in some, such as Naegleria and

Balantidium. Many protozoa have subpellicular microtubules# in the picomplexa,

which have no external organelles for locomotion, these provide a means for slow

movement. !he trichomonads and trypanosomes have a distinctive undulating

membrane between the body wall and a flagellum. Many other structures occur in

parasitic protozoa, including the <olgi apparatus, mitochondria, lysosomes, food

vacuoles, conoids in the picomplexa, and other specialized structures. 1lectron

microscopy is essential to visualize the details of protozoal structure. =rom the point

of view of functional and physiologic complexity, a protozoan is more li$e an animal

than li$e a single cell. =igure **&( shows the structure of the bloodstream form of a

trypanosome, as determined by electron microscopy.

4

,$G&R- ..-/ ,ine structure of a protozoan parasite) Trypanosoma evansi) as

re0ealed 1y transmission electron microcopy of thin sections" .dapted from

,ic$erman >? Protozoology. ,ol. @ 'ondon School of 2ygiene and !ropical

Medicine, 'ondon, (3**, with permission.0

Classification

In (3A8 the Society of Protozoologists published a taxonomic scheme that

distributed the Protozoa into six phyla. !wo of these phylathe

ife Cycle Sta!es

/uring its life cycle, a protozoan generally passes through several stages that

differ in structure and activity.

Trophozoite .<ree$ for ;animal that feeds;0 is a general term for the active,

feeding, multiplying stage of most protozoa. In parasitic species this is the

5

stage usually associated with pathogenesis. In the hemoflagellates the terms

amastigote, promastigote, epimastigote, and trypomastigote designate

trophozoite stages that differ in the absence or presence of a flagellum and in

the position of the $inetoplast associated with the flagellum. variety of

terms are employed for stages in the picomplexa, such as tachyzoite and

bradyzoite for Toxoplasma gondii. Other stages in the complex asexual and

sexual life cycles seen in this phylum are the

merozoite .the form resulting from fission of a multinucleate schizont0 and

sexual stages such as

!ametocytes and !ametes. Some protozoa form

cysts that contain one or more infective forms. Multiplication occurs in the

cysts of some species so that excystation releases more than one organism. =or

example, when the trophozoite of Entamoeba histolytica first forms a cyst, it

has a single nucleus. s the cyst matures nuclear division produces four nuclei

and during excystation four uninucleate metacystic amebas appear. Similarly,

a freshly encysted Giardia lamblia has the same number of internal structures

.organelles0 as the trophozoite. 2owever, as the cyst matures the organelles

double and two trophozoites are formed. 4ysts passed in stools have a

protective wall, enabling the parasite to survive in the outside environment for

a period ranging from days to a year, depending on the species and

environmental conditions. 4ysts formed in tissues do not usually have a heavy

protective wall and rely upon carnivorism for transmission. Oocysts are stages

resulting from sexual reproduction in the picomplexa. Some apicomplexan

oocysts are passed in the feces of the host, but the oocysts of Plasmodium, the

agent of malaria, develop in the body cavity of the mos"uito vector.

Reproduction

Beproduction in the Protozoa may be asexual, as in the amebas and flagellates

that infect humans, or 1oth asexual and sexual, as in the picomplexa of medical

importance. !he most common type of asexual multiplication is 1inary fission, in

which the organelles are duplicated and the protozoan then divides into two complete

organisms. %i0ision is lon!itudinal in the fla!ellates and trans0erse in the ciliates2

amebas have no apparent anterior&posterior axis.

6

-ndodyo!eny is a form of asexual division seen in Toxoplasma and some

related organisms. !wo daughter cells form within the parent cell, which then

ruptures, releasing the smaller progeny which grow to full size before

repeating the process. In

schizo!ony, a common form of asexual division in the picomplexa, the

nucleus divides a number of times, and then the cytoplasm divides into smaller

uninucleate merozoites" In Plasmodium, Toxoplasma, and other

apicomplexans, the sexual cycle involves the production of gametes

.!amo!ony0, fertilization to form the zygote, encystation of the zygote to form

an oocyst, and the formation of infective sporozoites .sporogony0 within the

oocyst.

Some protozoa have complex life cycles re"uiring two different host species#

others re"uire only a single host to complete the life cycle. single infective

protozoan entering a susceptible host has the potential to produce an immense

population. 2owever, reproduction is limited by events such as death of the host or by

the host-s defense mechanisms, which may either eliminate the parasite or balance

parasite reproduction to yield a chronic infection. =or example, malaria can result

when only a few sporozoites of Plasmodium falciparumperhaps ten or fewer in rare

instancesare introduced by a feeding Anopheles mos"uito into a person with no

immunity. Bepeated cycles of schizogony in the bloodstream can result in the

infection of (6 percent or more of the erythrocytesabout +66 million parasites per

milliliter of blood.

#utrition

!he nutrition of all protozoa is holozoic# that is, they re"uire organic materials,

which may be particulate or in solution. mebas engulf particulate food or droplets

through a sort of temporary mouth, perform digestion and absorption in a food

vacuole, and e:ect the waste substances. Many protozoa have a permanent mouth, the

cytosome or micropore, through which ingested food passes to become enclosed in

food vacuoles. Pinocytosis is a method of ingesting nutrient materials whereby fluid is

drawn through small, temporary openings in the body wall. !he ingested material

becomes enclosed within a membrane to form a food vacuole.

Protozoa have metabolic pathways similar to those of higher animals and

re"uire the same types of organic and inorganic compounds. In recent years,

7

significant advances have been made in devising chemically defined media for the in

vitro cultivation of parasitic protozoa. !he resulting organisms are free of various

substances that are present in organisms grown in complex media or isolated from a

host and which can interfere with immunologic or biochemical studies. Besearch on

the metabolism of parasites is of immediate interest because pathways that are

essential for the parasite but not the host are potential targets for antiprotozoal

compounds that would bloc$ that pathway but be safe for humans. Many

antiprotozoal drugs were used empirically long before their mechanism of action was

$nown. !he sulfa drugs, which bloc$ folate synthesis in malaria parasites, are one

example.

!he rapid multiplication rate of many parasites increases the chances for

mutation# hence, changes in virulence, drug susceptibility, and other characteristics

may ta$e place. 4hloro"uine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum and arsenic

resistance in Trypanosoma rhodesiense are two examples.

4ompetition for nutrients is not usually an important factor in pathogenesis

because the amounts utilized by parasitic protozoa are relatively small. Some parasites

that inhabit the small intestine can significantly interfere with digestion and

absorption and affect the nutritional status of the host# Giardia and Cryptosporidium

are examples. !he destruction of the host-s cells and tissues as a result of the parasites-

metabolic activities increases the host-s nutritional needs. !his may be a ma:or factor

in the outcome of an infection in a malnourished individual. =inally, extracellular or

intracellular parasites that destroy cells while feeding can lead to organ dysfunction

and serious or life&threatening conse"uences.

8

References

1nglund P!, Sher .eds0? !he %iology of Parasitism. Molecular and

Immunological pproach. lan B. 'iss, 9ew Cor$, (3AA

<oldsmith B, 2eyneman / .eds0? !ropical Medicine and Parasitology. ppleton and

'ange, 1ast 9orwal$, 4!, (3A3

'ee DD, 2utner S2, %ovee 14 .eds0? n Illustrated <uide to the Protozoa. Society of

Protozoologists, 'awrence, >S, (3A8

>otler /P, Orenstein DM? Prevalence of Intestinal Microsporidiosis in 2I,&infected

individuals referred for gastrointestinal evaluation. D <astroenterol A3? (33A,

(33+

9eva =, %rown 2? %asic 4linical Parasitology, )th edition, ppleton E 'ange,

9orwal$, 4!, (33+

9

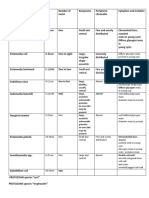

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- 1 IntroDocumento5 pagine1 IntroJeanjayannseptoemanNessuna valutazione finora

- Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention of LeishmaniasisDa EverandPathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention of LeishmaniasisMukesh SamantNessuna valutazione finora

- Tissue and Blood NematodesDocumento53 pagineTissue and Blood NematodesVincent ManganaanNessuna valutazione finora

- Hang Drop PDFDocumento2 pagineHang Drop PDFIndhumathiNessuna valutazione finora

- Morpholofy of MoDocumento44 pagineMorpholofy of MoPathumavathy RamanathanNessuna valutazione finora

- NematodaDocumento96 pagineNematodaPurplesmilezNessuna valutazione finora

- Pharmaceutical Biochemistry: A Comprehensive approachDa EverandPharmaceutical Biochemistry: A Comprehensive approachNessuna valutazione finora

- Arthropods of Medical ImportanceDocumento6 pagineArthropods of Medical ImportanceMiren Sofia Jordana0% (1)

- Rheumatic Fever: Causes, Tests, and Treatment OptionsDa EverandRheumatic Fever: Causes, Tests, and Treatment OptionsNessuna valutazione finora

- (Para) Introduction To Parasitology and Protozoology-Dr. Dela Rosa (Tiglao)Documento7 pagine(Para) Introduction To Parasitology and Protozoology-Dr. Dela Rosa (Tiglao)Arlene DaroNessuna valutazione finora

- Microbiology and Parasitology Presentation by W KakumuraDocumento14 pagineMicrobiology and Parasitology Presentation by W KakumurahamiltonNessuna valutazione finora

- Practical Manual for Detection of Parasites in Feces, Blood and Urine SamplesDa EverandPractical Manual for Detection of Parasites in Feces, Blood and Urine SamplesNessuna valutazione finora

- Pure Culture TechniqueDocumento6 paginePure Culture Techniquebetu8137Nessuna valutazione finora

- Micro-Para Finals ReviewerDocumento14 pagineMicro-Para Finals ReviewerFatima Mae MeLagroNessuna valutazione finora

- BELIZARIO VY Et Al Medical Parasitology in The Philippines 3e 158 226Documento69 pagineBELIZARIO VY Et Al Medical Parasitology in The Philippines 3e 158 226Sharon Agor0% (1)

- pm2 TREMATODESDocumento39 paginepm2 TREMATODESshastaNessuna valutazione finora

- Entamoeba ColiDocumento14 pagineEntamoeba ColiHanisha Erica100% (1)

- BACTERIA CULTURE PRES Rev1Documento28 pagineBACTERIA CULTURE PRES Rev1Jendie BayanNessuna valutazione finora

- Medical ProtozoologyDocumento6 pagineMedical ProtozoologyRaymund MontoyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Pathogenesis of Bacterial Infection and Nosocomial InfectionDocumento56 paginePathogenesis of Bacterial Infection and Nosocomial InfectionDenise Johnson0% (1)

- Zinsser Microbiology PDFDocumento2 pagineZinsser Microbiology PDFsccortesNessuna valutazione finora

- Bacterial Cell StructureDocumento6 pagineBacterial Cell StructureCasey StuartNessuna valutazione finora

- Hereditary SpherocytosisDocumento39 pagineHereditary SpherocytosisjoannaNessuna valutazione finora

- MycologyDocumento26 pagineMycologySkandi43Nessuna valutazione finora

- Amoebiasis and AmoebaDocumento10 pagineAmoebiasis and AmoebaStephanie Joy EscalaNessuna valutazione finora

- 1.introduction To ParasitologyDocumento32 pagine1.introduction To ParasitologyPallavi Uday Naik100% (1)

- Kato Katz TechniqueDocumento35 pagineKato Katz TechniqueJohn Paul Valencia100% (2)

- Parasitology PrelimsDocumento47 pagineParasitology PrelimsKim Delaney MadridNessuna valutazione finora

- Gram Negative Rods of Enteric TractDocumento2 pagineGram Negative Rods of Enteric TractJohn TerryNessuna valutazione finora

- Amoebiasis in Wild Mammals: Ayesha Ahmed M Phil. Parasitology 1 Semester 2013-Ag-2712Documento25 pagineAmoebiasis in Wild Mammals: Ayesha Ahmed M Phil. Parasitology 1 Semester 2013-Ag-2712Abdullah AzeemNessuna valutazione finora

- Difference Between Endotoxins and ExotoxinsDocumento6 pagineDifference Between Endotoxins and ExotoxinsJasna KNessuna valutazione finora

- Sputum CultureDocumento6 pagineSputum CulturePranav Kumar PrabhakarNessuna valutazione finora

- Egg Hunting GuideDocumento6 pagineEgg Hunting GuidesmilingfroggyNessuna valutazione finora

- Acid Fast StainingDocumento4 pagineAcid Fast Stainingchaudhary TahiraliNessuna valutazione finora

- Cestode SDocumento79 pagineCestode SVincent Manganaan67% (3)

- J201 Quiz IIDocumento5 pagineJ201 Quiz IItimweaveNessuna valutazione finora

- Bachelor of Science in Medical Technology 2014Documento6 pagineBachelor of Science in Medical Technology 2014Maxine TaeyeonNessuna valutazione finora

- MICROBIODocumento158 pagineMICROBIOJoyce VillanuevaNessuna valutazione finora

- Parasitology ProtozoansDocumento13 pagineParasitology ProtozoansMay LacdaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To ParasitologyDocumento44 pagineIntroduction To ParasitologyRIC JOSEPH PONCIANONessuna valutazione finora

- My CologyDocumento25 pagineMy CologyPlasma CarwashNessuna valutazione finora

- Bacterial Virulence FactorsDocumento55 pagineBacterial Virulence FactorsVINOTH100% (1)

- Bacteria - Morphology & ClassificationDocumento38 pagineBacteria - Morphology & ClassificationAfshan NasirNessuna valutazione finora

- Medical Parasitology PDFDocumento150 pagineMedical Parasitology PDFYajee Macapallag100% (1)

- Hereditary SpherocytosisDocumento16 pagineHereditary Spherocytosisrizi2008Nessuna valutazione finora

- Parasitology Lecture 4 - Atrial FlagellatesDocumento4 pagineParasitology Lecture 4 - Atrial Flagellatesmiguel cuevasNessuna valutazione finora

- Types of ImmunityDocumento35 pagineTypes of ImmunityKailash NagarNessuna valutazione finora

- Bates Chapter 8 Lung and ThoraxDocumento15 pagineBates Chapter 8 Lung and ThoraxAdrian CaballesNessuna valutazione finora

- S4 L5 SchistosomaDocumento5 pagineS4 L5 Schistosoma2013SecBNessuna valutazione finora

- Arthropods of Medical ImportanceDocumento6 pagineArthropods of Medical ImportanceMarlon Ursua BagalayosNessuna valutazione finora

- Belizario VicenteDocumento15 pagineBelizario VicenteRoshanDavidNessuna valutazione finora

- ProtozoaDocumento8 pagineProtozoaBhatara Ayi MeataNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 77protozoa: Structure, Classification, Growth, and DevelopmentDocumento7 pagineChapter 77protozoa: Structure, Classification, Growth, and DevelopmentGOWTHAM GUPTHANessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento7 pagineUntitledtedy yidegNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 77protozoaDocumento11 pagineChapter 77protozoaduraiakilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Citric Acid Cycle - Assignment Point Finel PDFDocumento19 pagineCitric Acid Cycle - Assignment Point Finel PDFRoshan PMNessuna valutazione finora

- Asf Adv-2380 FinalDocumento1 paginaAsf Adv-2380 FinalRoshan PMNessuna valutazione finora

- Impactofaudio Visualaids PublishedDocumento10 pagineImpactofaudio Visualaids Publishedmuhammad afzalNessuna valutazione finora

- 1Documento5 pagine1Roshan PM0% (1)

- Registration Form - Laptop SchemeDocumento1 paginaRegistration Form - Laptop SchemeRoshan PMNessuna valutazione finora

- Baluchistan Black Bear: Scientific ClassificationDocumento3 pagineBaluchistan Black Bear: Scientific ClassificationRoshan PMNessuna valutazione finora

- Research MethodolgyDocumento10 pagineResearch MethodolgyRoshan PMNessuna valutazione finora

- IntroductionDocumento19 pagineIntroductionRoshan PMNessuna valutazione finora

- Impact of Mimicry of Politicians in PakistaniDocumento25 pagineImpact of Mimicry of Politicians in PakistaniRoshan PMNessuna valutazione finora

- Internship Report On Nishat Textile MillsDocumento3 pagineInternship Report On Nishat Textile MillsKamran KhalidNessuna valutazione finora

- The Halal Slaughter ControvesyDocumento5 pagineThe Halal Slaughter ControvesyRoshan PMNessuna valutazione finora

- The Halal Slaughter ControvesyDocumento5 pagineThe Halal Slaughter ControvesyRoshan PMNessuna valutazione finora

- Animal Rights and IslamDocumento9 pagineAnimal Rights and IslamRoshan PMNessuna valutazione finora

- Big Bite Shawarma Bread (PVT) : Order Book No 1Documento2 pagineBig Bite Shawarma Bread (PVT) : Order Book No 1Roshan PMNessuna valutazione finora

- Final Islamic Slaughtering and Meat QualityDocumento9 pagineFinal Islamic Slaughtering and Meat QualityRoshan PMNessuna valutazione finora

- Impact of Advertisement On The Life Style of Pakistani YouthDocumento14 pagineImpact of Advertisement On The Life Style of Pakistani YouthRoshan PMNessuna valutazione finora

- Impact of Advertisement On The Life Style of Pakistani YouthDocumento14 pagineImpact of Advertisement On The Life Style of Pakistani YouthRoshan PMNessuna valutazione finora

- Policy ImplementationDocumento16 paginePolicy ImplementationRoshan PMNessuna valutazione finora

- Policy ImplementationDocumento16 paginePolicy ImplementationRoshan PMNessuna valutazione finora

- Bs. English BLAKEDocumento12 pagineBs. English BLAKERoshan PMNessuna valutazione finora

- BSPA Presentation On TerrorismDocumento21 pagineBSPA Presentation On TerrorismRoshan PMNessuna valutazione finora

- Policy ImplementationDocumento16 paginePolicy ImplementationRoshan PMNessuna valutazione finora

- Assignment PoetsDocumento13 pagineAssignment PoetsRoshan PM0% (1)

- The Prose WriterDocumento3 pagineThe Prose WriterRoshan PM0% (1)

- Hasan Bin SultanDocumento8 pagineHasan Bin SultanRoshan PMNessuna valutazione finora

- 1111 No 2Documento38 pagine1111 No 2Roshan PMNessuna valutazione finora

- Characteristics of Romantic AgeDocumento2 pagineCharacteristics of Romantic AgeRoshan PM83% (6)

- Pakistan TelecommunicationsDocumento1 paginaPakistan TelecommunicationsRoshan PMNessuna valutazione finora

- The Prose WriterDocumento3 pagineThe Prose WriterRoshan PM0% (1)

- Chapter 77 Protozoa: Structure, Classification, Growth, and DevelopmentDocumento7 pagineChapter 77 Protozoa: Structure, Classification, Growth, and DevelopmentMegbaruNessuna valutazione finora

- Entamoeba Coli: BackgroundDocumento4 pagineEntamoeba Coli: BackgroundJam Pelario100% (1)

- P2 REVIEWER (Part 2)Documento6 pagineP2 REVIEWER (Part 2)ArllrNessuna valutazione finora

- Hulda Clark - Frequency TableDocumento9 pagineHulda Clark - Frequency Tablesfeterman100% (10)

- Introduction To FecalysisDocumento3 pagineIntroduction To FecalysisseanleeqtNessuna valutazione finora

- GI Tract InfectionsDocumento29 pagineGI Tract InfectionsMahrukh SiddiquiNessuna valutazione finora

- Frequency ChartDocumento12 pagineFrequency ChartGeorgina ĐukićNessuna valutazione finora

- (MT 57) PARA - Specimen CollectionDocumento10 pagine(MT 57) PARA - Specimen CollectionLiana JeonNessuna valutazione finora

- Bato Balani Vol. 20 No. 1 SY 2000-2001Documento24 pagineBato Balani Vol. 20 No. 1 SY 2000-2001Annie MayNessuna valutazione finora

- Protozoa 99Documento14 pagineProtozoa 99ENI NURRIFANTINessuna valutazione finora

- Lec 10 CiliatesDocumento11 pagineLec 10 CiliatesRam RamNessuna valutazione finora

- Giardia LambliaDocumento40 pagineGiardia LambliaKotilakshmanareddy TetaliNessuna valutazione finora

- Mdparas NotesDocumento46 pagineMdparas NotesnamkimseoNessuna valutazione finora

- Balantidium Coli PDFDocumento15 pagineBalantidium Coli PDFNona MhomedNessuna valutazione finora

- Rhizopoda: Parasitology Department Medical Faculty University of Sumatera UtaraDocumento32 pagineRhizopoda: Parasitology Department Medical Faculty University of Sumatera UtaraAngela FovinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Flotation LabDocumento17 pagineFlotation LabChinyere ObiNessuna valutazione finora

- Lbbbi18 Long Exam 1Documento71 pagineLbbbi18 Long Exam 1namkimseoNessuna valutazione finora

- 1.entamoeba Histolytica - Is The Major Pathogen in This GroupDocumento14 pagine1.entamoeba Histolytica - Is The Major Pathogen in This GroupJoseph De JoyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Summary Table of AmoebaDocumento5 pagineSummary Table of AmoebaFatty BalotoNessuna valutazione finora

- Multiple Choice Questions (1.5point Each) : Allowed Time 1: 30hrDocumento2 pagineMultiple Choice Questions (1.5point Each) : Allowed Time 1: 30hrdawit nigusieNessuna valutazione finora

- محاضرة سادسة رابع نظريDocumento7 pagineمحاضرة سادسة رابع نظريaust austNessuna valutazione finora

- Parasites and The Food SupplyDocumento10 pagineParasites and The Food SupplyZamora Olvera Sandra SofíaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Full Moon Parasite Cleanse ProtocolDocumento49 pagineThe Full Moon Parasite Cleanse ProtocolparthvarandaniNessuna valutazione finora

- PARASITLOGY Quick Quiz 1Documento18 paginePARASITLOGY Quick Quiz 1Joseph Enoch Elisan100% (1)

- Intestinal and Genital Flagellates-EditDocumento7 pagineIntestinal and Genital Flagellates-EditChristianAvelinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Classification: Phylum: Metamonada Class: Trepomanadea Order: Giardida Family: Giardidae Genus: GiardiaDocumento21 pagineClassification: Phylum: Metamonada Class: Trepomanadea Order: Giardida Family: Giardidae Genus: GiardiaLohith MCNessuna valutazione finora

- ProtozoaDocumento26 pagineProtozoaAbul VafaNessuna valutazione finora

- Practical Logbook: Medical Parasitology Department GIT Module 104Documento16 paginePractical Logbook: Medical Parasitology Department GIT Module 104Kareem DawoodNessuna valutazione finora

- EXO Notes - Parasitology - Intro To paraDocumento12 pagineEXO Notes - Parasitology - Intro To paraEdmarie GuzmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Intestinal Parasitosis: For The Ethiopian Health Center TeamDocumento137 pagineIntestinal Parasitosis: For The Ethiopian Health Center TeamStefan LucianNessuna valutazione finora

- A Brief History of Intelligence: Evolution, AI, and the Five Breakthroughs That Made Our BrainsDa EverandA Brief History of Intelligence: Evolution, AI, and the Five Breakthroughs That Made Our BrainsValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (6)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisDa EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityDa EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (4)

- The Molecule of More: How a Single Chemical in Your Brain Drives Love, Sex, and Creativity--and Will Determine the Fate of the Human RaceDa EverandThe Molecule of More: How a Single Chemical in Your Brain Drives Love, Sex, and Creativity--and Will Determine the Fate of the Human RaceValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (517)

- Masterminds: Genius, DNA, and the Quest to Rewrite LifeDa EverandMasterminds: Genius, DNA, and the Quest to Rewrite LifeNessuna valutazione finora

- Gut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerDa EverandGut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (393)

- Tales from Both Sides of the Brain: A Life in NeuroscienceDa EverandTales from Both Sides of the Brain: A Life in NeuroscienceValutazione: 3 su 5 stelle3/5 (18)

- Who's in Charge?: Free Will and the Science of the BrainDa EverandWho's in Charge?: Free Will and the Science of the BrainValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (65)

- Gut: The Inside Story of Our Body's Most Underrated Organ (Revised Edition)Da EverandGut: The Inside Story of Our Body's Most Underrated Organ (Revised Edition)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (411)

- 10% Human: How Your Body's Microbes Hold the Key to Health and HappinessDa Everand10% Human: How Your Body's Microbes Hold the Key to Health and HappinessValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (33)

- Fast Asleep: Improve Brain Function, Lose Weight, Boost Your Mood, Reduce Stress, and Become a Better SleeperDa EverandFast Asleep: Improve Brain Function, Lose Weight, Boost Your Mood, Reduce Stress, and Become a Better SleeperValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (15)

- All That Remains: A Renowned Forensic Scientist on Death, Mortality, and Solving CrimesDa EverandAll That Remains: A Renowned Forensic Scientist on Death, Mortality, and Solving CrimesValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (397)

- Undeniable: How Biology Confirms Our Intuition That Life Is DesignedDa EverandUndeniable: How Biology Confirms Our Intuition That Life Is DesignedValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (11)

- The Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of EvolutionDa EverandThe Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of EvolutionValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (812)

- Good Without God: What a Billion Nonreligious People Do BelieveDa EverandGood Without God: What a Billion Nonreligious People Do BelieveValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (66)

- The Other Side of Normal: How Biology Is Providing the Clues to Unlock the Secrets of Normal and Abnormal BehaviorDa EverandThe Other Side of Normal: How Biology Is Providing the Clues to Unlock the Secrets of Normal and Abnormal BehaviorNessuna valutazione finora

- Seven and a Half Lessons About the BrainDa EverandSeven and a Half Lessons About the BrainValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (109)

- Human: The Science Behind What Makes Your Brain UniqueDa EverandHuman: The Science Behind What Makes Your Brain UniqueValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (38)

- Lymph & Longevity: The Untapped Secret to HealthDa EverandLymph & Longevity: The Untapped Secret to HealthValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (13)

- The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs: A New History of a Lost WorldDa EverandThe Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs: A New History of a Lost WorldValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (595)

- A Series of Fortunate Events: Chance and the Making of the Planet, Life, and YouDa EverandA Series of Fortunate Events: Chance and the Making of the Planet, Life, and YouValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (62)

- The Consciousness Instinct: Unraveling the Mystery of How the Brain Makes the MindDa EverandThe Consciousness Instinct: Unraveling the Mystery of How the Brain Makes the MindValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (93)

- Buddha's Brain: The Practical Neuroscience of Happiness, Love & WisdomDa EverandBuddha's Brain: The Practical Neuroscience of Happiness, Love & WisdomValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (216)

- Wayfinding: The Science and Mystery of How Humans Navigate the WorldDa EverandWayfinding: The Science and Mystery of How Humans Navigate the WorldValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (18)

- Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap Between Us and ThemDa EverandMoral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap Between Us and ThemValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (115)

- Crypt: Life, Death and Disease in the Middle Ages and BeyondDa EverandCrypt: Life, Death and Disease in the Middle Ages and BeyondValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (4)