Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Benefits of Globalization For The Developing Countries

Caricato da

Mudassir HabibTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Benefits of Globalization For The Developing Countries

Caricato da

Mudassir HabibCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Journal Identication = JPO Article Identication = 5905 Date: April 18, 2011 Time: 10:40 am

Journal of Policy Modeling 33 (2011) 511521

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

Does globalization benet developing countries?

Effects of FDI on local wages

Akinori Tomohara

a,c,

, Sadayuki Takii

b,1

a

University of California Los Angeles, Anderson Forecast, United States

b

The International Centre for the Study of East Asian Development, Japan

c

Aoyama Gakuin University, Japan

Received 1 August 2010; received in revised form 12 October 2010; accepted 1 December 2010

Available online 20 January 2011

Abstract

Twodifferent reactions toglobalization(either supportingor opposingglobalization) are observedthrough-

out the world. Focusing on the effects on the labor market, we examine whether foreign direct investment

benets workers employed by local establishments in a host developing country. The analysis shows that

they received wages above the market-based wage that would otherwise prevail in the absence of foreign

establishments. Although concerns exist that growing multinational business might have negative impacts

on local workers, this paper suggests that those fears might be unwarranted.

2011 Society for Policy Modeling. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

JEL classication: F21; F 23; J31

Keywords: FDI; Wage spillovers; Equity; Globalization; Multinational companies

1. Introduction

Does globalization really improve standards of living in developing countries? This question

is of signicant policy concern in the area of economic development. International organi-

An earlier draft of this paper was prepared while the rst author visited the ICSEAD as a visiting scholar. The

rst author also would like to thank to seminar participants at Western Economic Association International 81st Annual

Conference, Osaka University, and University of Pittsburgh for their comments. Specically, we would like to thank to

Robert Lipsey and Eric Ramstetter for their support for this project. All errors are ours.

Corresponding author at: University of California Los Angeles, Anderson Forecast, 835 Nesconset Hwy. G4, Nescon-

set, NY 11767, United States. Tel.: +1 718 997 5456; fax: +1 718 997 5466.

E-mail addresses: jujodai@yahoo.com (A. Tomohara), takii@icsead.or.jp (S. Takii).

1

Research Department, The International Centre for the Study of East Asian Development, Kitakyushu, 11-4 Otemachi

KokuraKita, Kitakyushu Fukuoka, 803-0814, Japan. Tel.: +81 93 583 6202; fax: +81 93 583 4603.

0161-8938/$ see front matter 2011 Society for Policy Modeling. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.jpolmod.2010.12.010

Journal Identication = JPO Article Identication = 5905 Date: April 18, 2011 Time: 10:40 am

512 A. Tomohara, S. Takii / Journal of Policy Modeling 33 (2011) 511521

zations advocate the merit of accessing the global economy via foreign direct investment.

Anti-globalization movements do not necessarily agree with this view. Those opposing glob-

alization argue that self-interested, multinational companies exploit the resources of developing

countries and impair development. Thus, for the purposes of long-run economic growth, it is

better to protect domestic infant industries rather than rely on foreign capital.

Several (anti-)globalization issues have been explored in the literature: topics include income

inequality across countries (Adams, 2008; Galbraith, 2007; Lee, 2006), and foreign direct invest-

ment (FDI) and economic growth (Laureti &Postiglione, 2005; Qin, Cagas, Quising, &He, 2006)

(refer to Bhagwati (2004) and Intriligator (2004) for overview).

Our study is motivated by wage gaps between foreign multinational companies and domestic

companies (Aitken, Harrison, &Lipsey, 1996 for Mexico and Venezuela; Lipsey &Sjholm, 2004

for Indonesia). Multinational companies tend to pay higher wages than domestic companies, even

after controlling for factors such as industry and worker characteristics. Globalization apparently

does not benet workers employed by domestic companies according to our observations of

wage inequality in a host country. Wage inequality attributable to FDI is a major policy concern

in developing countries. The government advises foreign and local establishments to remedy the

gaps.

We examine whether higher wages set by foreign establishments, operating in a developing

country, affect the wage levels of local establishments. Local establishments may enjoy increased

wages in the presence of FDI. The analysis utilizes empirical models used in the literature on

the key-industry hypothesis (Christodes, Swidinsky, & Wilton, 1980; Drewes, 1987; Lee &

Pesaran, 1993; Mehra, 1976; Shinkai, 1980; Smith, 1996). The hypothesis treats the wage set by

a key-industry as a reference wage. The literature examines whether wage determination by a

key industry affects wage levels of other industries. Our analysis employs a similar methodology.

Foreign establishments often dominate the market in developing countries. Their behaviors inu-

ences host countries economies. Assuming foreign establishments are wage-decision leaders, we

explore whether wages set by foreign establishments have externalities on the wage determination

of local establishments (i.e., wage spillovers).

We consider wage spillovers using the Indonesian manufacturing industry during 19891996.

The time period chosen corresponds to a period of foreign investment liberalization in Indonesia

and, thus, a period when Indonesia experienced a large FDI inow. The Indonesian case is one

good example for understanding this topics political importance.

Analyses showthat wage spillovers occur fromforeign establishments to local establishments.

Higher wages set by foreign establishments increase the wage levels of local establishments.

Employees in Indonesian local establishments enjoy increased wages in the presence of FDI. A

spillover channel results from a reference wage effect, which operates through equity concerns

and bargaining. Observing wage gaps, employees in local establishments may feel that they are

unduly underpaid and might therefore negotiate for higher wages. Therefore, wages paid by

foreign establishments impose an externality, a non-market-based wage determination, on wages

paid by local establishments.

The results are robust even if we assume restricted labor mobility and examine a sub-sample.

Furthermore, we examine whether wage spillovers differ between large wage-gap industries and

small wage-gap industries. The results indicate that a reference wage plays an important role in

determining the wage levels of local establishments in large wage-gap industries but not in small

wage-gap industries.

Our analysis suggests newpolicyimplications relatedtothe effects of FDI onthe labor market in

host countries. This paper presents analyses that are distinct fromthose of earlier works describing

Journal Identication = JPO Article Identication = 5905 Date: April 18, 2011 Time: 10:40 am

A. Tomohara, S. Takii / Journal of Policy Modeling 33 (2011) 511521 513

wage spillovers. We include two different channels through which foreign establishments affect

local establishments wage decisions. A higher level of FDI could increase local establishments

wages via increased productivity. Previous works mainly consider this possibility. We introduce

non-market factors, specically equity and bargaining considerations, into the argument. The

literature points out the creation of job opportunities as a benet of FDI. The current analysis

adds possible positive wage spillovers to the argument.

The paper proceeds as follows. In Section 2, we summarize the data used for the analysis.

Section 3 describes an empirical model for studying wage spillovers. Results of the analysis are

presented in Section 4. Section 5 concludes the paper and suggests future lines of research.

2. Data

We use data based on an annual manufacturing survey conducted by the Central Bureau of

Statistics (CBS), Republic of Indonesia (Biro Pusat Statistik, Republik Indonesia) from 1989

to 1996. The Industrial Statistics Division of CBS (Biro Statistik Industri) conducts industrial

surveys on manufacturing establishments with 20 or more employees. The survey provides infor-

mation on industrial classication, the type of ownership (public, private, and foreign), location,

labor (number and salary/wages), xed assets, material and electricity costs, income, output, etc.

The survey data is commonly used in the literature on Indonesian industry analysis [e.g., the

relationships between FDI and technology spillovers (Blalock & Gertler, 2004; Takii, 2005);

wage gaps between domestic and multinational companies (Lipsey & Sjholm, 2004)]. Data on

Wholesale Price Index (WPI) is obtained from Monthly Statistical Bulletin. Additionally, we

calculate provincial unemployment rates from the labor force and unemployment data in Labor

Force Situation in Indonesia.

We use a panel dataset for Indonesian manufacturing from 1989 to 1996. The presence of

foreign establishments increased rapidly during the period, making it relevant for analyzing wage

spillovers. In fact, Indonesia experienced foreign investment liberalization during the time period

and, subsequently, a large FDI inow. After oil prices collapsed in the mid-1980s, Indonesia

tried to reduce dependency on oil and gas revenue. This effort resulted in policies encouraging

FDI during the late 1980s and early 1990s. Annual FDI inows increased tenfold from US$ 0.6

billion in 1988 to US$ 6.2 billion in 1996 until the Asian nancial crisis struck the economy in

19971998 (ICSEAD, 2005, Table 7.2, pp. 107110). The number of foreign establishments in

manufacturing sectors nearly doubled during the sample period from 708 in 1991 to 1318 in 1996

(Table 1). Another reason for the chosen time period is technical. Our empirical analysis employs

the ArellanoBond estimation method. The method uses differenced and lagged variables with

two or more periods as instruments. In the survey dataset, capital stock (at the beginning of period)

is available from 1989. Thus, we set up the effective sample period as 19911996 and use data

from 1989 to 1996 to estimate our empirical model (see Section 3 for details).

Table 1 presents the samples summary statistics. We have 27,066 observations (about 4500

plants for each year) after eliminating outliers and establishments with missing variables.

2

The

sample includes 29 industries at the 3-digit ISIClevel. We observe a signicant difference between

wages paid by local establishments and the ones paid by foreign establishments. A local estab-

lishments wage level is about one-third of a foreign establishments wage level. The ratio of

2

Our analysis focuses on local establishments that stay in the market for ve years or more. Thus, the positive wage

spillovers shown in this paper are not the results of efciency improvements, made possible as foreign establishment let

some inefcient local establishments exit from the market.

Journal Identication = JPO Article Identication = 5905 Date: April 18, 2011 Time: 10:40 am

514 A. Tomohara, S. Takii / Journal of Policy Modeling 33 (2011) 511521

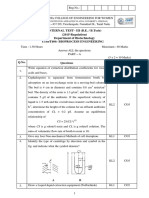

Table 1

Summary statistics of the sample.

19911996 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996

Variables Mean Std. dev. Mean Mean Mean Mean Mean Mean

Local wage 1855 1608 1376 1538 1740 1910 2152 2318

Capital 8862 30,681 7188 7255 8591 9066 9980 10,727

Number of labor 261 904 248 255 253 266 266 276

Material 14,494 50,481 10,915 12,120 12,473 14,722 17,265 18,862

The ratio of non-production workers 16.59 15.49 16.94 16.96 16.85 16.71 16.31 15.8

Plant size 9224 75,014 5919 6998 8073 9439 10,934 13,517

Value added 7060 18,121 5273 6042 6306 7453 8070 8908

Sample size (Local) 27,066 3763 4269 4908 4790 5232 4104

Foreign wage 5257 5387 4097 4442 4786 5125 5647 6537

Sample size (Foreign) 708 897 991 1121 1200 1318

Number of industries 29 29 29 29 29 29 29

Units: Rupiah 1000 (except size that uses Rupiah million); all variables are measured by a per-employee unit at an

establishment level except the number of labor, plant size, and the ratio of non-production worker (%).

Source: Annual manufacturing survey by Indonesian Central Bureau of Statistics.

non-production workers is around 16% throughout the sample period. Standard deviations indi-

cate characteristic variations among establishments and across industries. We will control for

these observed characteristics, and other macroeconomic factors, such as unemployment rates in

the following empirical analysis.

3. Model

We construct a model of local establishments wage determination by referring to empirical

models used in the key-industry hypothesis literature. The literature on wage spillovers is clas-

sied as either a regional interaction or inter-industry interaction (including interactions such as

union vs. non-union sectors). The latter includes Latreille and Manning (2000), Lee and Pesaran

(1993), Mehra (1976), Shinkai (1980), Smith (1996) and Vroman (1982). Drewes (1987) is an

example of regional interaction for wage determination i.e., companies in the same region affect

the determination of wage levels each other. Christodes et al. (1980) and Drifeld and Girma

(2003) are spatial economy studies, and include both regional and industrial interactions. Despite

these differences, empirical models used in the wage spillovers literature do employ a similar

specication, including explanatory variables.

Wage spillovers from foreign establishments to local establishments are examined by the

following dynamic panel data model:

w

d

it

=

1

w

d

it1

+

2

k

it

+

3

va

it

+

4

w

f

jt1

+

5

wpi

jt

+

x

it

+

t

+

i

+

it

,

where w

d

it

is the wage paid by a local establishment i in year t, k

it

is capital per employee at

the beginning of year t, va

it

is value added per employee, w

f

jt1

is a weighted-average wage of

foreign establishments in industry j that i belongs to in year t 1, wpi

jt

is WPI for industry j,

and x

it

contains a set of control variables. As in the original survey, value added is dened as

total sales minus expenditures for capital and labor inputs. A time effect,

t

, controls for time

varying elements that affect all establishments in a given year. An individual effect,

i

, captures

Journal Identication = JPO Article Identication = 5905 Date: April 18, 2011 Time: 10:40 am

A. Tomohara, S. Takii / Journal of Policy Modeling 33 (2011) 511521 515

time invariant elements that differ across establishments and/or industries.

3

An error term,

it

,

is assumed to be independently distributed across individual establishments. All variables are

measured in logarithm units.

Following the standard denition of MNCs, we classify an establishment foreign if 10% or

more of a rms equity is foreign equity. Foreign equity is the share of equity held by foreigners at

the establishment level. The weighted-average wage of foreign establishments, w

f

jt

, is calculated

as

m

r=1

rt

w

rt

, where

rt

is a weight and m is the total number of foreign establishments in

industry j that a local establishment i belongs to. The weight,

rt

, is the fraction such that the

number of employees in an establishment, r, is divided by the total number of employees in

all foreign establishments in industry j. We make use of the redesigned Indonesian industrial

classication at the ISIC 3-digit level.

4

The vector, x

it

, is the set of observable characteristics that inuence wage levels. The vector

controls for the differences among establishments. Observable characteristics include material

costs per employee, the ratio of non-production workers, provincial unemployment rates, and plant

sizes (which are measured by the previous years output). We cannot control for some differences

in workers characteristics. The survey does not have information (e.g., workers age) or give

complete information for the analysis (e.g., workers educational levels are available from 1995

forward and gender is available from 1993 forward). Other possible unobservable characteristics

that may inuence wage levels are controlled by a time effect,

t

, and an establishment effect,

i

.

Standard economic theory explains how wages are determined in the market. Prot maximiza-

tion requires wages to be equal to marginal revenue product (or marginal revenue multiplied by

marginal product). In the competitive market, this is expressed as w = P MP

L

, where w is a

nominal wage, P is the price of nal goods, and MP

L

is the marginal product of labor. The terms

of capital intensity, k

it

, and WPI, wpi

jt

, incorporate the idea. The level of the marginal product

of labor is a function of capital (Aitken et al., 1996, p. 348; Blomstrm & Sjholm, 1999, p. 917;

Drifeld & Girma, 2003, p. 457; Smith, 1996, p. 501). WPI is used to proxy for the price of goods

in each industry. The simple textbook explanation for determining wages is a static approach.

In our model, we include a dynamic wage decision process. One may regard the previous years

wage as a reference in deciding this years wage. Thus, wage levels are further adjusted based on

previous years wages, w

d

it1

.

In reality, wages are also determined by non-market factors. One example is an externality

such that wages set by foreign establishments affects the wage paid by domestic employers. Our

analysis distinguishes two wage spillover effects. The rst is wage spillovers via technology

spillovers. Increased wages of local establishments could be explained by increased productivity.

The second is wage spillovers introducing equity and bargaining considerations.

We include a value added term to capture the former wage spillovers. As local establishments

absorb foreign establishments advanced technologies, the result of foreign direct investment is

increased productivity. Other development that is not related to FDI (e.g., locally incurred tech-

nology progress) also increases productivity. The value added term controls for wage spillovers

via any productivity increases.

5

This approach is consistent with the literature on technology

3

One may suggest separating time invariant elements into industry xed effects and establishment xed effects. Our

results are not sensitive to the treatment since our estimation method takes the rst difference.

4

Oil-related industries (ISIC 353 and 354) are not included in the sample. The data on foreign establishments in the

industries seem to suffer extensively from missing information and are inappropriate for the analysis.

5

Previous works implicitly assumes a kind of causality between value added and wages.

Journal Identication = JPO Article Identication = 5905 Date: April 18, 2011 Time: 10:40 am

516 A. Tomohara, S. Takii / Journal of Policy Modeling 33 (2011) 511521

spillovers, where the literature examines possible technology spillovers by using a model to eval-

uate whether FDI increases local companies value added (Blomstrm & Sjholm, 1999; Caves,

1974; Globerman, 1979; Haddad & Harrison, 1993; Kokko, 1994).

We also consider wage spillover channels introducing a reference wage effect. Local establish-

ments may increase wages in order to match wages paid by foreign establishments. This could

be explained by equity and bargaining considerations. As in the literature on fair wage (in which

the wage set by a leading company or industry affects wage determination by other companies or

industries), foreign establishments wages could serve as a reference wage. Employees working

at local establishments may feel unfair if their wages are far below wages paid for comparable

work by foreign establishments. Wage increases also encourage employees to work harder. These

wage spillover effects are captured by the coefcient,

4

. If

4

>0, then employees in local estab-

lishments benet from the activities of foreign establishments. Local establishments wages are

set higher due to positive wage spillovers from foreign establishments.

We use the generalized method of moments (GMM) proposed by Arellano and Bond (1991)

to estimate the dynamic model using panel data. The GMM is a standard method for estimating a

model using panel data when the model contains a lagged dependent variable with an unobserved

effect. The GMM is relevant to estimate our empirical model, which includes a lagged dependent

variable, w

it1

, and an unobserved effect,

i

. The method uses the levels of endogenous variables

dated t 2 and before as instruments in a rst difference model. Estimation is conducted by using

the DPD98 program for Gauss (see Arellano and Bond (1998) for the programs details).

4. Results of the analysis

Table 2 summarizes the results. Columns (1), (2), (5) and (6) showthe results using observations

dated t 2 and t 3 as instruments. Columns (3), (4), (7) and (8) are the results using observations

dated t 2 and all past observations as instruments. The left half of the table summarizes estimates

of the nationwide sample. The right half of the table presents estimates of a sub-sample (i.e.,

establishments in Java and Sumatra islands).

6

The results showthat the foreign establishments have positive externalities on the wage level of

local establishments even after controlling for value added. We observe wage spillovers resulting

from a reference wage effect. The wage level of local establishments increases by 45% for 1%

increase in the wages paid by the foreign establishment. The foreign establishments impose an

externality, a non-market-based wage determination, on the wages paid by local establishments.

The results imply that local establishments try to reduce wage gaps between foreign and local

establishments.

Employees in Indonesian local establishments enjoy higher wages because of FDI through

a spillover channel resulting from a reference wage effect. The effect operates through equity

concerns and bargaining. Employees working at local establishments may become disgruntled

if their wages are far below wages paid by foreign establishments. Local establishments may

need to alleviate wage gaps between local and foreign establishments in order to keep workers

and/or motivate workers efforts. Similarly, workers bargain with their employers using outside

work opportunities as the threat point. The presence of multinational companies offering a higher

6

Table 2 reports the m

2

statistic to examine the relevance of the ArellanoBond estimation method. The consistency

of the GMM estimators requires the assumption of no serial correlation in

it

. The m

2

statistic tests for lack of second-

order serial correlation in the rst-difference residuals. The m

2

statistic in Table 2 shows that the assumption of serially

uncorrelated errors seems to be appropriate. The test for rst-order serial correlation also shows a negative relationship.

Journal Identication = JPO Article Identication = 5905 Date: April 18, 2011 Time: 10:40 am

A. Tomohara, S. Takii / Journal of Policy Modeling 33 (2011) 511521 517

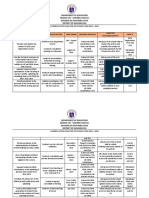

Table 2

Analysis of wage spillovers.

Nationwide Java-Sumatra

Variables (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8)

Domestic wage (1)

0.441 0.427 0.449 0.434 0.451 0.437 0.461 0.444

0.018 0.019 0.017 0.018 0.017 0.02 0.018 0.019

Capital

0.03 0.024 0.03 0.023 0.03 0.023 0.029 0.022

0.005 0.005 0.005 0.005 0.005 0.005 0.005 0.005

Value added

0.081 0.1 0.081 0.101 0.081 0.101 0.081 0.103

0.005 0.005 0.005 0.005 0.006 0.005 0.006 0.005

MNC wage

0.051 0.048 0.045 0.042 0.052 0.05 0.048 0.046

0.014 0.014 0.013 0.013 0.014 0.014 0.014 0.014

WPI (ISIC 3-digit)

0.163 0.204 0.16 0.202 0.149 0.19 0.134 0.181

0.045 0.045 0.045 0.044 0.046 0.046 0.046 0.045

The ratio of non-production workers

0.067 0.069 0.067 0.069 0.068 0.069 0.069 0.068

0.009 0.009 0.009 0.009 0.009 0.01 0.009 0.009

Unemployment rates (Province)

0.007 0.006 0.008 0.007 0.007 0.006 0.008 0.007

0.002 0.002 0.002 0.002 0.002 0.002 0.002 0.002

Material

0.059 0.062 0.056 0.064

0.013 0.012 0.014 0.013

Plant size

0.055 0.054 0.057 0.05

0.014 0.014 0.015 0.015

Time dummies Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Constant

0.065 0.06 0.064 0.059 0.064 0.058 0.062 0.058

0.007 0.006 0.007 0.006 0.007 0.006 0.007 0.006

m

2

test statistics 1.941 1.737 2.047 1.826 0.937 0.801 1.028 0.876

Sargan test 116.03 100.59 136.19 123.6 111.2 91.86 138.1 120.5

Sargan test-degree of freedom 31 21 46 36 31 21 46 36

Top values are coefcient estimates and bottom values are standard errors. All point estimates are statistically signicant

at 5% level (we use standard errors and test statistics corrected for heteroskedasticity). The numbers of observations are

27,066 for (1)(4) and 24,710 for (5)(8). Columns (1), (2), (5) and (6) are estimated in rst differences using observation

dated t 2 and t 3 as instruments and columns (3), (4), (7) and (8) are estimated using observation dated t 2 and all

past observations as instruments.

wage could raise the equilibrium wage in domestic companies. These factors also increase local

establishments wages.

The analysis examines the effects of wage spillovers within industry, when workers are freely

movable across the country. Since Indonesia consists of many islands, labor mobility may be

restricted. We introduce restricted labor mobility into the analysis. Further analysis assumes

that workers are movable between two large neighborhoods; Java and Sumatra islands only. We

examine the key industry hypothesis using the Java and Sumatra islands as a sub-sample. The

right half of the table presents the results from the sub-sample. The results, both direction and

magnitude, are similar to the ones obtained in the nationwide analysis. The results are robust,

even when using different samples.

We conclude that promoting foreign establishments benets employees of local establishments.

They received wages above the market-based wage that would prevail in the absence of foreign

establishments. While there are concerns that growing multinational business might have negative

impacts on local workers, our analysis suggests that the fear might be unwarranted.

Other variables indicate expected coefcient signs that are in agreement with economic theory.

Wages increase as capital or the ratio of non-production employees increases. Non-production

Journal Identication = JPO Article Identication = 5905 Date: April 18, 2011 Time: 10:40 am

518 A. Tomohara, S. Takii / Journal of Policy Modeling 33 (2011) 511521

workers (i.e., managers) receive a higher wage. A higher wage level is the result of a higher

level of marginal product of labor, from w = P MP

L

. The marginal product of labor increases

with capital, and is larger for non-production workers. The results also show that wages are

positively correlated with unemployment rates. Intuitively, when the economy is suffering from

a recession, employees with lower marginal products are the rst ones who will lose their jobs.

Those with a higher marginal product of labor retain their jobs. Another possible interpretation

is that the term operates as an urban dummy. Larger cities often offer higher wages and, thus,

attract many workers. As the HarrisTodaro model states, higher expected wages may end up

with higher unemployment rates. The estimate captures an idiosyncratic cross-regional effect,

i.e., time variant regional shocks. All estimates in the table are statistically signicant at the 5%

level.

4.1. The level of wage gaps

We classify the sample into two sub-samples and examine whether a different policy impli-

cation is derived depending on industrial characteristics. The rst is industries with large wage

gaps between local and foreign establishments. The second is industries with small wage gaps

between local and foreign establishments. The analysis examines whether there are any differences

regarding wage spillovers between the two groups. This study is analogous to previous works on

technology spillovers. The literature examines whether the spillover effects are different between

industries with large technology gaps and small technology gaps. The results are controversial.

Some works show that only industries with small technology gaps benet. Small-gap industries

already possess the basic technology necessary for adoption of the more advanced technology.

Primitive industries are unable to utilize advanced technology. Production processes used by

primitive domestic companies may differ inherently from the ones by multinational companies.

Other works show that technology spillovers are effective only when there are large technology

gaps. When there are large technology gaps, the possibilities for learning are much greater.

We stratify the sample using the following procedure. We begin to calculate an industry-wide

wage gap between local and foreign establishments each year. Then, we calculate the average

industry-wide wage gap during the sample period.

7

We order these industry-wide average wage

gaps from the smallest to the largest at the ISICs last two-digit level and split industries into two

groups. The large wage-gap group includes 14 industries such as chemicals, iron and steel, and

electronics. The small wage-gap group includes 15 industries such as food, textiles, and paper.

The classication is stable during the sample period. The industry ordering based on average

wage gaps during the sample period is consistent with the ordering based on average wage gaps

from 1989 to 1991.

Table 3 shows the results for this part of our analysis. Columns labeled large represent large

wage gap industries and columns labeled small represent small wage gap industries. Columns

(1)(4) show the results using observations dated t 2 and t 3 as instruments. Columns (5)(8)

present the results using observations dated t 2 and all past observations as instruments. The

table summarizes estimates of the nationwide sample.

The results differ from those in the previous section regarding wage spillovers. A reference

wage plays an important role in determining wages of domestic companies in large-gap industries,

7

An industry-wide wage gap is calculated as ( w

f

jt

w

d

jt

)/ w

d

jt

, where w

f

jt

is an average foreign wage in industry j for

year t and w

d

jt

is an average local wage in industry j for year t.

Journal Identication = JPO Article Identication = 5905 Date: April 18, 2011 Time: 10:40 am

A. Tomohara, S. Takii / Journal of Policy Modeling 33 (2011) 511521 519

Table 3

Large wage gap vs. small wage gap industries.

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8)

Variables Large Small Large Small Large Small Large Small

Domestic wage (1) 0.416

*

0.450

*

0.415

*

0.422

*

0.422

*

0.442

*

0.425

*

0.413

*

0.026 0.023 0.027 0.024 0.025 0.022 0.026 0.024

Capital 0.031

*

0.026

*

0.026

*

0.018

*

0.029

*

0.026

*

0.025

*

0.017

*

0.007 0.006 0.008 0.006 0.007 0.006 0.007 0.006

Value added 0.078

*

0.082

*

0.097

*

0.102

*

0.079

*

0.082

*

0.099

*

0.102

*

0.008 0.008 0.008 0.007 0.008 0.007 0.008 0.007

MNC wage 0.046

*

0.044

***

0.047

*

0.034 0.036

**

0.037 0.037

**

0.029

0.016 0.025 0.016 0.025 0.015 0.025 0.015 0.025

WPI (ISIC 3-digit) 0.260

*

0.038 0.287

*

0.090 0.272

*

0.028 0.299

*

0.074

0.065 0.071 0.067 0.068 0.065 0.070 0.066 0.067

The ratio of non-production workers 0.079

*

0.041

*

0.080

*

0.047

*

0.081

*

0.039

*

0.082

*

0.043

*

0.012 0.012 0.013 0.013 0.012 0.012 0.012 0.012

Unemployment rates (Province) 0.004 0.009

*

0.004 0.007

**

0.005 0.010

*

0.005 0.009

*

0.003 0.003 0.003 0.003 0.003 0.003 0.003 0.003

Material 0.061

*

0.049

*

0.064

*

0.046

*

0.017 0.018 0.016 0.017

Plant size 0.043

**

0.070

*

0.041

**

0.071

*

0.018 0.020 0.018 0.020

Time dummies Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Constant 0.065

*

0.070

*

0.064

*

0.062

*

0.065

*

0.072

*

0.064

*

0.062

*

0.008 0.010 0.008 0.010 0.009 0.010 0.008 0.009

m

2

test statistics 1.65

***

0.65 1.37 0.81 1.71

***

0.61 1.44 0.74

Sargan test 101.71

*

52.9

*

87.63

*

40.97

*

122.14

*

68.9

**

104.26

*

58.31

*

Sargan test-degree of freedom 31 31 21 21 46 46 36 36

Top values are coefcient estimates and bottom values are standard errors (we use standard errors and test statistics

corrected for heteroskedasticity). The number of observations are 14,631 for large and 12,435 for small. We use DPD98

described in Arellano and Bond (1998) for estimation. Lagged dependent variable was instrumented by its level dated

t 2 and t 3 in columns (1)(4) and by t 2 and all available past observations in columns (5)(8). Capital, the ratio of

non-production workers, material, and plant size were instrumented by corresponding levels dated t 1.

*

Statistically signicant at 1% level.

**

Statistically signicant at 5% level.

***

Statistically signicant at 10% level.

but not in small-gap industries. The row MNC wage shows that the wage level paid by local

establishments in large-gap industries increases by approximately 5%if foreign establishments in

large-gapindustries increase their wages by1%. We donot see statisticallysignicant relationships

regarding wage interaction between local and foreign establishments in small-gap industries. We

can conclude that employees working for local establishments in large-gap industries beneted

fromthe countries hosting foreign establishments. Large-gap industry employees received higher

wages due to a reference wage effect. Estimates using the sub-sample of Java and Sumatra islands

(not shown in the table) show similar results.

Two alternative scenarios arise in our wage spillover analysis. First, one may expect larger

wage spillovers when larger wage gaps between local and foreign establishments exist. Observing

large wage gaps, employees in local establishments may feel that they are unduly underpaid and

negotiate harder for their wages. The second possible scenario is that employers may not have

the sense of equity concern if the two establishments differ intrinsically. Employers in local

Journal Identication = JPO Article Identication = 5905 Date: April 18, 2011 Time: 10:40 am

520 A. Tomohara, S. Takii / Journal of Policy Modeling 33 (2011) 511521

establishments may tolerate receiving a lower wage. Our analysis reveals that the rst scenario is

relevant in the Indonesian case.

5. Conclusions

People react to globalization differently: some support it and others oppose it. Various argu-

ments are possible depending on our concerns. Specically regarding the effects of globalization

on the labor market, this paper presents an examination of whether foreign direct investment ben-

ets workers employed by local companies via increased wages. The analysis utilizes empirical

models used in the literature on the key-industry hypothesis. Assuming foreign establishments

are wage-decision leaders, we study whether wages set by foreign establishments have exter-

nalities on wage determination by local establishments. The analysis shows that the activities of

foreign establishments benet employees in local establishments by increasing wages for local

establishments employees. The effects operate through a reference wage concerns. The litera-

ture frequently highlights job creation as a benet of FDI. The results of the current analysis

add positive wage effect to the list of FDIs possible benets. Our analysis also indicates that a

reference wage plays an important role in local establishments determination of wage levels in

large wage-gap industries, but not in small wage-gap industries.

Our model can be applied to explore other interesting questions. First, our model does not

deny spatial interaction among local establishments. For example, Drifeld and Girma (2003)

consider spatial interactions of wages in the UK electronics industry. Using wages of local and

multinational companies as independent variables, their empirical model examines the degree to

which these wages affect local companies wage decisions in an industry. Our analysis studies the

case where foreign establishments are a leader regarding wage decisions. Local establishments

wages are a function of foreign establishments wages. One may want to interpret our model

as a reduced form, where local establishments wages are solved as a function of foreign

establishments wages. While our analysis is motivated by a different policy concern from the

wage spillover literature in a spatial economy, our model specication does not deny possible

wage interactions among local establishments.

Second, one has to careful interpreting the results if the degree of wage spillover effects

differs across skilled and unskilled workers. The survey data do not provide skilled and unskilled

workers wages separately. The analysis tries to adjust wage differences related to skilled or

unskilled workers by including the non-production share as an explanatory variable. The results

do not change if the degree of wage spillovers is the same between skilled and unskilled workers.

Otherwise, the results provide a kind of weighted average of both types of workers.

Last, wage spillovers could be decomposed into vertical (backward and forward) and hori-

zontal externalities. Foreign establishments may affect wage decisions of local establishments

that provide intermediate goods to the foreign establishments (i.e., backward effects). Foreign

establishments may also affect wage decisions of local establishments to which the foreign

establishments sell their goods (i.e., forward effects). The analysis focuses on horizontal wage

spillovers, where foreign establishments affect wage decisions of local establishments within the

same industry. Such analysis requires additional information, including an inputoutput table to

relate different industries. All of these topics are future lines of research.

References

Adams, S. (2008). Globalization and income inequality: Implications for intellectual property rights. Journal of Policy

Modeling, 30, 725735.

Journal Identication = JPO Article Identication = 5905 Date: April 18, 2011 Time: 10:40 am

A. Tomohara, S. Takii / Journal of Policy Modeling 33 (2011) 511521 521

Aitken, B., Harrison, A., &Lipsey, R. E. (1996). Wages and foreign ownership: Acomparative study of Mexico, Venezuela,

and the United States. Journal of International Economics, 40(3), 345371.

Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specication for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to

employment equations. Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277297.

Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1998). Dynamic panel data estimation for using DPD98 for Gauss: A guide for users.

ftp://ftp.cem.es/pdf/papers/ma/dpd98.pdf.

Bhagwati, J. (2004). Anti-globalization: Why? Journal of Policy Modeling, 26, 439463.

Blalock, G., & Gertler, P. J. (2004). Firm capabilities and technology adoption: Evidence from foreign direct investment

in Indonesia. Mimeo. Cornell University.

Blomstrm, M., & Sjholm, F. (1999). Foreign direct investment, technology transfer and spillovers: Does local partici-

pation with multinationals matter? European Economic Review, 43, 915923.

Caves, R. E. (1974). Multinational rms, competition, and productivity in host-country markets. Economica, 41, 176193.

Christodes, L. N., Swidinsky, R., &Wilton, D. A. (1980). Amicroeconometric analysis of spillovers within the Canadian

wage determination process. Review of Economics and Statistics, 62(2), 213221.

Drewes, T. (1987). Regional wage spillover in Canada. Review of Economics and Statistics, 69(2), 224231.

Drifeld, N., & Girma, S. (2003). Regional foreign direct investment and wage spillovers: Plant level evidence from the

UK electronics industry. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 65(4), 453474.

Galbraith, J. K. (2007). Global inequality and global macroeconomics. Journal of Policy Modeling, 29, 587607.

Globerman, S. (1979). Foreign direct investment and spillover efciency benets on Canadian manufacturing industries.

Canadian Journal of Economics, 12, 4256.

Haddad, M., & Harrison, A. (1993). Are there positive spillovers from direct foreign investment? Evidence from panel

data for Morocco. Journal of Development Economics, 42, 5174.

ICSEAD. (2005). Recent trends and prospects for major Asian economies. East Asian Economic Perspectives 14 (1).

Kitakyushu: ICSEAD.

Intriligator, M. D. (2004). Globalization of the world economy: Potential benets and costs and a net assessment. Journal

of Policy Modeling, 26, 485498.

Kokko, A. (1994). Technology, market characteristics, and spillovers. Journal of Development Economics, 43, 279293.

Latreille, P. L., &Manning, N. (2000). Inter-industry and inter-occupational wage spillovers in UKmanufacturing. Oxford

Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 62(1), 8399.

Laureti, L., & Postiglione, P. (2005). The effects of capital inows on the economic growth in the Med Area. Journal of

Policy Modeling, 27, 839851.

Lee, J.-E. (2006). Inequality and globalization in Europe. Journal of Policy Modeling, 28, 791796.

Lee, K. C., &Pesaran, M. H. (1993). The role of sectorial interactions in wage determination in the UKeconomy. Economic

Journal, 103(416), 2155.

Lipsey, R. E., &Sjholm, F. (2004). Foreign direct investment, education and wages in Indonesian manufacturing. Journal

of Development Economics, 73, 415422.

Mehra, Y. P. (1976). Spillovers inwage determinationinU.S. manufacturingindustries. Reviewof Economics andStatistics,

58(3), 300312.

Qin, D., Cagas, M. A., Quising, P., & He, X.-H. (2006). How much does investment drive economic growth in China?

Journal of Policy Modeling, 28, 751774.

Shinkai, Y. (1980). Spillovers in wage determination: Japanese evidence. Review of Economics and Statistics, 62(2),

288292.

Smith, J. C. (1996). Wage interactions: Comparisons or fall-back options? Economic Journal, 106(435), 495506.

Takii, S. (2005). Productivity spillovers and characteristics of foreign multinational plants in Indonesian manufacturing

19901995. Journal of Development Economics, 76, 521542.

Vroman, S. (1982). The direction of wage spillovers in manufacturing. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 36(1),

102112.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Saet Work AnsDocumento5 pagineSaet Work AnsSeanLejeeBajan89% (27)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- CA Inter Group 1 Book November 2021Documento251 pagineCA Inter Group 1 Book November 2021VISHAL100% (2)

- Methodical Pointing For Work of Students On Practical EmploymentDocumento32 pagineMethodical Pointing For Work of Students On Practical EmploymentVidhu YadavNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Create A Powerful Brand Identity (A Step-by-Step Guide) PDFDocumento35 pagineHow To Create A Powerful Brand Identity (A Step-by-Step Guide) PDFCaroline NobreNessuna valutazione finora

- Ludwig Van Beethoven: Für EliseDocumento4 pagineLudwig Van Beethoven: Für Eliseelio torrezNessuna valutazione finora

- Year 9 - Justrice System Civil LawDocumento12 pagineYear 9 - Justrice System Civil Lawapi-301001591Nessuna valutazione finora

- Enerparc - India - Company Profile - September 23Documento15 pagineEnerparc - India - Company Profile - September 23AlokNessuna valutazione finora

- Algorithmique Et Programmation en C: Cours Avec 200 Exercices CorrigésDocumento298 pagineAlgorithmique Et Programmation en C: Cours Avec 200 Exercices CorrigésSerges KeouNessuna valutazione finora

- Rebar Coupler: Barlock S/CA-Series CouplersDocumento1 paginaRebar Coupler: Barlock S/CA-Series CouplersHamza AldaeefNessuna valutazione finora

- Online EarningsDocumento3 pagineOnline EarningsafzalalibahttiNessuna valutazione finora

- Appendix - 5 (Under The Bye-Law No. 19 (B) )Documento3 pagineAppendix - 5 (Under The Bye-Law No. 19 (B) )jytj1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Subqueries-and-JOINs-ExercisesDocumento7 pagineSubqueries-and-JOINs-ExerciseserlanNessuna valutazione finora

- 5 Deming Principles That Help Healthcare Process ImprovementDocumento8 pagine5 Deming Principles That Help Healthcare Process Improvementdewi estariNessuna valutazione finora

- Epidemiologi DialipidemiaDocumento5 pagineEpidemiologi DialipidemianurfitrizuhurhurNessuna valutazione finora

- Historical Development of AccountingDocumento25 pagineHistorical Development of AccountingstrifehartNessuna valutazione finora

- A PDFDocumento2 pagineA PDFKanimozhi CheranNessuna valutazione finora

- Basic DfwmacDocumento6 pagineBasic DfwmacDinesh Kumar PNessuna valutazione finora

- Discover Mecosta 2011Documento40 pagineDiscover Mecosta 2011Pioneer GroupNessuna valutazione finora

- Personal Best B1+ Unit 1 Reading TestDocumento2 paginePersonal Best B1+ Unit 1 Reading TestFy FyNessuna valutazione finora

- Ucm6510 Usermanual PDFDocumento393 pagineUcm6510 Usermanual PDFCristhian ArecoNessuna valutazione finora

- Reference Template For Feasibility Study of PLTS (English)Documento4 pagineReference Template For Feasibility Study of PLTS (English)Herikson TambunanNessuna valutazione finora

- CV Ovais MushtaqDocumento4 pagineCV Ovais MushtaqiftiniaziNessuna valutazione finora

- Cic Tips Part 1&2Documento27 pagineCic Tips Part 1&2Yousef AlalawiNessuna valutazione finora

- KSU OGE 23-24 AffidavitDocumento1 paginaKSU OGE 23-24 Affidavitsourav rorNessuna valutazione finora

- Action Plan Lis 2021-2022Documento3 pagineAction Plan Lis 2021-2022Vervie BingalogNessuna valutazione finora

- A Novel Adoption of LSTM in Customer Touchpoint Prediction Problems Presentation 1Documento73 pagineA Novel Adoption of LSTM in Customer Touchpoint Prediction Problems Presentation 1Os MNessuna valutazione finora

- Health Insurance in Switzerland ETHDocumento57 pagineHealth Insurance in Switzerland ETHguzman87Nessuna valutazione finora

- Binary File MCQ Question Bank For Class 12 - CBSE PythonDocumento51 pagineBinary File MCQ Question Bank For Class 12 - CBSE Python09whitedevil90Nessuna valutazione finora

- How To Control A DC Motor With An ArduinoDocumento7 pagineHow To Control A DC Motor With An Arduinothatchaphan norkhamNessuna valutazione finora

- CNC USB English ManualDocumento31 pagineCNC USB English ManualHarold Hernan MuñozNessuna valutazione finora