Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Porn Studies: To Cite This Article: Nathaniel Burke (2014) Positionality and Pornography, Porn Studies, 1:1-2

Caricato da

cliodna18Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Porn Studies: To Cite This Article: Nathaniel Burke (2014) Positionality and Pornography, Porn Studies, 1:1-2

Caricato da

cliodna18Copyright:

Formati disponibili

This article was downloaded by: [180.253.244.

224]

On: 22 March 2014, At: 02:49

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered

office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Porn Studies

Publication details, including instructions for authors and

subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rprn20

Positionality and pornography

Nathaniel Burke

a

a

Department of Sociology, University of Southern California, USA

Published online: 21 Mar 2014.

To cite this article: Nathaniel Burke (2014) Positionality and pornography, Porn Studies, 1:1-2,

71-74, DOI: 10.1080/23268743.2014.882646

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/23268743.2014.882646

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the

Content) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,

our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to

the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions

and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,

and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content

should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources

of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,

proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or

howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising

out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any

substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,

systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &

Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-

and-conditions

Positionality and pornography

Nathaniel Burke*

Department of Sociology, University of Southern California, USA

(Received 18 August 2013; accepted 12 September 2013)

As pornography continues to open up as a valued field of academic inquiry,

consideration should be given to the researchers position, both within the field

and within the academy, and how these two positions influence knowledge

production. The study of pornography, as a stigmatized subject, has an impact on

who can write about it, what they can write, and where that writing is published.

How this impacts what we know about pornography, how we can overcome these

barriers, and larger questions about positionality in the academy and the field are

discussed.

Keywords: pornography; fieldwork; positionality; ethnography; knowledge

production

This paper draws on my experiences of studying pornography as an ethnographer

and as a junior scholar, and addresses the methodological and epistemological

considerations that are unique to this field of study. Positionality in the study of

pornography is worth considering, not as a gratuitous gesture (Robertson 2002,

788) toward insider status or intellectual infallibility, but as significant to the

development of future scholarship. Although my position as a multiracial, queer,

middle-class, educated male cannot be separated from my position as an academic,

in this discussion I focus on academic positionality and its relation to research

subjects rather than on issues of gender, race, class, sexuality, and citizenship.

My academic training comes from a sociology department with strengths in

ethnographic methods. On the day that I was given access to observe an adult film

studios sets and offices, I was asked by my department to meet our undergraduate

honors students. I introduced myself: Im Nathaniel and I study the adult film

industry. The undergraduates gasped in unison and a collective buzz conveyed tones

varying from excitement and interest to clear disapproval. This reaction toward my

work is not uncommon and I open with this story to emphasize that pornography is a

charged topic, even and perhaps especially so for those in the academy, and to

highlight that these reactions create several barriers to the breadth and depth of

knowledge produced, the types and quality of work produced, the avenues available

for dissemination, and the audience of the scholarship. Through a discussion of

positionality, I will speak to these barriers that must be addressed in order for

pornography to be more widely accepted as a worthwhile field of study in the academy.

*Email: nathaniel.burke@usc.edu

Porn Studies, 2014

Vol. 1, Nos. 12, 7174, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/23268743.2014.882646

2014 Taylor & Francis

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

8

0

.

2

5

3

.

2

4

4

.

2

2

4

]

a

t

0

2

:

4

9

2

2

M

a

r

c

h

2

0

1

4

I have been told You dont want to be the porn guy and you will have to

deal with the content issue of your work. These are comments I take to be

supportive and made with the intention of positioning my academic career for

success on the job market and as productive of work that will garner respect in the

academy and in my discipline. While these comments came from scholars who

appreciate and see the value in my work and wish for me to succeed, their caution

has two clear implications. The first implication concerns who gets to write about

pornography and the second is about appropriate disciplinary lenses. Graduate

students may become vulnerable because of the subjects they choose to study.

Research on stigmatized topics such as pornography is more easily done as a tenured

faculty member. What this may mean for the future of the academy, the

development of research, and for individuals as they select their topics is worth

consideration. There are potentially fewer scholars studying stigmatized subjects who

can address the breadth of topics in pornography and plumb their depths, and

possibly less diversity demographically, a factor that may reduce the potential for

challenging and developing existing frameworks and methods.

Interrelated with the first barrier is the second: the types and quality of work

produced. My work, as is true for many scholars who study pornography, addresses

issues of gender, race, class, the body, sexuality, citizenship, and power. Yet in

sociology there are lenses through which it is more and less acceptable to study the

social world. This academic morality implies that there are some vectors of social life

that have more worth than others and are therefore more deserving of study. In

pornography, people perform sex acts that involve, perpetuate, or may challenge

inequalities. Justifications for studying it, such as the size of the industry or the

number of people it employs, should not be necessary it is a lens into the social

world deserving of inquiry that can help answer questions about workplace practices,

power relations, workers rights and health, and the reproduction of inequality.

Sociologys aversion to pornography as a site to study society occurs for three

broad reasons. First, the study of sexualities is marginalized within sociology.

Second, pornography is seen by some as a site of violence and its study may be

perceived as legitimating violence. Finally, those rooted in positivist traditions may

fear that the study of adult film is unscientific depending upon the selected

methodology. As Patricia Hill Collins (2013) notes, it is precisely the flexibility of

sociology that makes it resilient, creative, and exciting the ebbs and flows of

content areas such as pornography are what keep the discipline alive. Yet the

stigmatization of studying pornography impacts not only how it is studied and which

scholars are able to undertake its study, but also the avenues available for the

dissemination of scholarship and the kinds of audiences who receive it. Where work

on pornography appears is important for its adoption into core theories of the

discipline and for whether it becomes part of a broader public knowledge about

pornography.

Addressing these barriers through ones position requires a great deal of work;

the call for reflexivity and careful attention to positionality present unique challenges

to the study of pornography. Scholars who wish to shed light on the silence in the

study of pornography must be careful not to understand themselves as giving voice

to those unable to speak (see Alcoff 1991). Academics are not the only ones having

intelligent, informed, and productive discussions about the industry.

72 N. Burke

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

8

0

.

2

5

3

.

2

4

4

.

2

2

4

]

a

t

0

2

:

4

9

2

2

M

a

r

c

h

2

0

1

4

As researchers we are held to high expectations in our relationships with research

subjects; editors call for scholars to address what kind of work one may have done in

a fieldsite, which for scholars of pornography means potentially exposing histories of

sex work and production. For example, I have set up and taken down sets, fetched

drinks, food, condoms and lubricant for actors, observed and participated in casting

discussions, taken behind-the-scenes photographs, and served as a back-up camera-

man. I did this work with great consideration of the impact it may have had toward

my data; my labour was a form of remuneration for allowing me to spend time in

their space. Calls for reflexivity can be a challenge for researchers of pornography:

readers wish to know how you participated in your research, related to research

subjects, and how subjects understood your role in the fieldsite. This information

may be incompletely or incorrectly interpreted as participating in the production of

adult film, which may cause some to dismiss the legitimacy of the work as complicity

in its production, as opposed to critical engagement with the processes of labour.

The stance an ethnographer selects relative to research subjects can address some

of these challenges. My experience has been that acting as complete observer or

complete participant (Gold 1958) is not successful, although for different reasons.

Being a complete observer disrupted a shoot, as performers wanted to know about

my study, while to be a complete participant would depend on being already

involved in the industry in some way; an involvement that may further stigmatize the

researcher within the academic community. For these reasons it is easier to limit our

role to an observer-as-participant who has the privilege to selectively engage in

industry activities while foregrounding their role as researcher.

Inevitably, the position one takes in research design and data collection has a

bearing on the final written product. I have found that the relationship between my

writing and the people I study places me in a complicated position. I consider myself

a feminist as my research interests orient me toward addressing gender and sexual

inequality. When I entered my current fieldsite, I was interested in how these

inequalities are constituted in the production of gay adult film through hiring and

directing processes. My goal was to produce professional/political sociology (see

Burawoy 2005) that highlights the potential problems and strategies of subordinated

groups, such as men of subordinated masculinities and men of colour (see Connell

and Messerschmidt 2005; Connell 2005), in a field of labour. By doing so, my hope is

that others can mobilize to reduce these inequalities. This standpoint, however,

problematizes the work that porn workers are doing as it positions them as potentially

constitutive or complicit in the production of inequality. Because of this, engaging

research subjects in the writing process or sharing results is a delicate issue. It is

difficult to articulate to performers and producers that my role as a researcher is not to

make moral judgments of pornography, and that I respect their labour, while also

maintaining that I am engaged in an ongoing critique of the problematic conditions

under which work can occur. A conscious presentation-of-self (Goffman 1959) must

be carried out so as not to have critique misunderstood as disapproval.

In conclusion, scholarship on pornography within sociology faces several

barriers, each of these impacted by ones position within the academy, the field,

and the written work. As pornography continues to open up as a valued field of

study in various disciplines, we should subject these barriers and the benefits of

dismantling them to continuous consideration through the position we take as a

scholar. What kinds of theoretical interventions, for example, may become available

Porn Studies 73

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

8

0

.

2

5

3

.

2

4

4

.

2

2

4

]

a

t

0

2

:

4

9

2

2

M

a

r

c

h

2

0

1

4

by opening up the opportunity for alternative ethnographic stances in the study of

sex work? Would being more receptive to the voices of complete participants

challenge the stigmatization of sex workers and thereby address some of the concerns

of false consciousness levied against them?

Stacey and Thorne (1985) argue that the academy must be reconstructed to

address the demographic inequalities that have influenced the theoretical trajectories

of disciplines. Part of this reconstruction, I contend, must be an acknowledgement of

the hierarchical structure of the academy itself and how this shapes which topics are

deemed valuable and appropriate for study. Those scholars who adopt a more

complicated relationship with the study of sexual labour rightly point out that we

have a great deal more to explore (see, for example, Bernstein 2007; Weitzer 2009). I

argue that this exploration is incomplete until it is open to researchers at all levels,

utilizing all methods, and from diverse theoretical perspectives. How can we address

the intractability of the academy so that it is more readily open to the study of new

topics in new ways? To answer this question requires that we consider how the topics

we explore are structured by capitalism through the relationship between academic

research and academic employment. How can we further the research of stigmatized

topics or better yet, destigmatize them without separating intellectual exploration

from employment viability?

References

Alcoff, Linda. 1991. The Problem of Speaking for Others. Cultural Critique 20: 532.

Bernstein, Elizabeth. 2007. Sex Work for the Middle Classes. Sexualities 10 (4): 473488.

Burawoy, Michael. 2005. 2004 ASA Presidential Address: For Public Sociology. American

Sociological Review 70 (1): 428.

Collins, Patricia Hill. 2013. On Intellectual Activism. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University

Press.

Connell, Raewyn. 2005. Masculinities. 2nd ed. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of

California Press.

Connell, Raewyn, and James W. Messerschmidt. 2005. Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking

the Concept. Gender & Society 19 (6): 829859.

Goffman, Erving. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Doubleday.

Gold, Raymond L. 1958. Roles in Sociological Field Observations. Social Forces 36:

217223.

Robertson, Jennifer. 2002. Reflexivity Redux: A Pithy Polemic on Positionality. Anthro-

pological Quarterly 75 (4): 785792.

Stacey, Judith, and Barrie Thorne. 1985. The Missing Feminist Revolution in Sociology.

Social Problems 32 (4): 301316.

Weitzer, Ronald. 2009. Sociology of Sex Work. Annual Review of Sociology 35: 213234.

74 N. Burke

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

8

0

.

2

5

3

.

2

4

4

.

2

2

4

]

a

t

0

2

:

4

9

2

2

M

a

r

c

h

2

0

1

4

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Logic As The Science of Pure ConceptDocumento13 pagineLogic As The Science of Pure Conceptcliodna18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Your Song: Elton John Arrangement by LonelypickerDocumento3 pagineYour Song: Elton John Arrangement by Lonelypickercliodna18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Menulis TesisDocumento7 pagineMenulis Tesiscliodna18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Realism A Defensible DoctrineDocumento9 pagineRealism A Defensible Doctrinecliodna18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Silabus Critical TheoryDocumento2 pagineSilabus Critical Theorycliodna18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Conservatism A State of FieldDocumento21 pagineConservatism A State of Fieldcliodna18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Toward Theory of AntiliteratureDocumento16 pagineToward Theory of Antiliteraturecliodna18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Reflections - Can Utopianism Exist Without Intent?Documento7 pagineReflections - Can Utopianism Exist Without Intent?cliodna18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Future Conditional - Feminist Theory, New HistoricismDocumento8 pagineFuture Conditional - Feminist Theory, New Historicismcliodna18Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Essence of HumanismDocumento7 pagineThe Essence of Humanismcliodna18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Milner, Andrew - Changing The Climate. The Politics of DystopiaDocumento13 pagineMilner, Andrew - Changing The Climate. The Politics of DystopiaMiguelAlonsoOrtegaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Textual Space On The Notion of TextDocumento14 pagineThe Textual Space On The Notion of Textcliodna18Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Problem of Social Change in Technological Society - MarcuseDocumento16 pagineThe Problem of Social Change in Technological Society - Marcusecliodna18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Migration As HopeDocumento11 pagineMigration As Hopecliodna18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Barthes Structural NarrativeDocumento37 pagineBarthes Structural NarrativeAngela PalmitessaNessuna valutazione finora

- Shapes The Past and FutureDocumento20 pagineShapes The Past and Futurecliodna18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Perron, Paul. Narratology and Text - Subjectivity and Identity in New France and Québécois LiteratureDocumento5 paginePerron, Paul. Narratology and Text - Subjectivity and Identity in New France and Québécois Literaturecliodna18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Social Content of Science FictionDocumento23 pagineSocial Content of Science Fictioncliodna18Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Logic of Retribution - Amiri Baraka DutchmanDocumento9 pagineThe Logic of Retribution - Amiri Baraka Dutchmancliodna18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Shohat On 1492Documento6 pagineShohat On 1492cliodna18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Seminar: Historiography of The Aesthetic DisciplinesDocumento2 pagineSeminar: Historiography of The Aesthetic Disciplinescliodna18Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Reading of Dissonance of HarmonyDocumento24 pagineA Reading of Dissonance of Harmonycliodna18Nessuna valutazione finora

- On Fate and FatalismDocumento20 pagineOn Fate and Fatalismcliodna18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Topics BC Thesis 2011Documento5 pagineTopics BC Thesis 2011cliodna18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Terry 08 ComedyDocumento15 pagineTerry 08 Comedycliodna18Nessuna valutazione finora

- On Fate and FatalismDocumento20 pagineOn Fate and Fatalismcliodna18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lords of Misrule - Hostility To Aristocracy in Late Nineteenth - and Early Twentieth-Century BritainDocumento2 pagineLords of Misrule - Hostility To Aristocracy in Late Nineteenth - and Early Twentieth-Century Britaincliodna18Nessuna valutazione finora

- IngotsDocumento3 pagineIngotscliodna18Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Letm19 ValuesDocumento16 pagineLetm19 Valuesgretelabelong10Nessuna valutazione finora

- El Accommodations and Modifications ChartDocumento2 pagineEl Accommodations and Modifications Chartapi-490969974Nessuna valutazione finora

- Salma Keropok LosongDocumento6 pagineSalma Keropok LosongPutera ZXeeNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson 1Documento19 pagineLesson 1NORHAFIZAH BT. ABD. RASHID MoeNessuna valutazione finora

- Biting PolicyDocumento1 paginaBiting PolicyJulie PeaseyNessuna valutazione finora

- Item Analysis and ValidityDocumento49 pagineItem Analysis and Validitygianr_6Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cbc-Evaluation-Instrument Acp NC IiDocumento6 pagineCbc-Evaluation-Instrument Acp NC IiDanny R. SalvadorNessuna valutazione finora

- ATGB3673 Estimating Buildsoft Assignment BriefDocumento5 pagineATGB3673 Estimating Buildsoft Assignment BriefSamantha LiewNessuna valutazione finora

- Midterm Portfolio ENG 102Documento10 pagineMidterm Portfolio ENG 102colehyatt5Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sistem Persamaan LinearDocumento13 pagineSistem Persamaan LinearAdi Deni PratamaNessuna valutazione finora

- Quarter 3, Week 2 - 2021-2022Documento12 pagineQuarter 3, Week 2 - 2021-2022Estela GalvezNessuna valutazione finora

- Diplomarbeit: Trauma and The Healing Potential of Narrative in Anne Michaels's Novels"Documento177 pagineDiplomarbeit: Trauma and The Healing Potential of Narrative in Anne Michaels's Novels"Maryam JuttNessuna valutazione finora

- Dreams PDFDocumento8 pagineDreams PDFapi-266967947Nessuna valutazione finora

- Case 5a The Effectiveness of Computer-Based Training at Falcon Insurance CompanyDocumento3 pagineCase 5a The Effectiveness of Computer-Based Training at Falcon Insurance Companyoliana zefi0% (1)

- Item Analysis and Test BankingDocumento23 pagineItem Analysis and Test BankingElenita-lani Aguinaldo PastorNessuna valutazione finora

- D1 Collocation&idiomsDocumento4 pagineD1 Collocation&idiomsvankhanh2414Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Initiations of The Seventh RayDocumento303 pagineThe Initiations of The Seventh Rayfsdfgsdgd100% (1)

- Behavior Modification Principles and Procedures 5Th Edition Miltenberger Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDocumento19 pagineBehavior Modification Principles and Procedures 5Th Edition Miltenberger Test Bank Full Chapter PDFtylerayalaardbgfjzym100% (10)

- Numerical Aptitude TestDocumento8 pagineNumerical Aptitude TestNashrah ImanNessuna valutazione finora

- ASYN Rodriguez PN. EssayDocumento1 paginaASYN Rodriguez PN. EssayNatalie SerranoNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan Reading Year 2 English KSSR Topic 5 I Am SpecialDocumento4 pagineLesson Plan Reading Year 2 English KSSR Topic 5 I Am SpecialnonsensewatsonNessuna valutazione finora

- Grade 9 HealthDocumento42 pagineGrade 9 Healthapi-141862995100% (1)

- McRELTeacher Evaluation Users GuideDocumento63 pagineMcRELTeacher Evaluation Users GuideVeny RedulfinNessuna valutazione finora

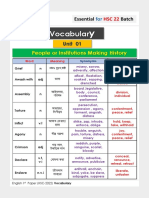

- Vocabulary HSC 22 PDFDocumento28 pagineVocabulary HSC 22 PDFMadara Uchiha83% (6)

- ST Clair County Help CardDocumento2 pagineST Clair County Help CardddddddddddddddddddddddNessuna valutazione finora

- Nursing OSCEs A Complete Guide To Exam SuccessDocumento250 pagineNursing OSCEs A Complete Guide To Exam SuccessTa Ta88% (8)

- Research Experience 9781506325125Documento505 pagineResearch Experience 9781506325125Cameron AaronNessuna valutazione finora

- Sociology Project Introducing The Sociological Imagination 2nd Edition Manza Test BankDocumento18 pagineSociology Project Introducing The Sociological Imagination 2nd Edition Manza Test Bankangelafisherjwebdqypom100% (13)

- Imperialism Lesson PlanDocumento3 pagineImperialism Lesson Planapi-229326247Nessuna valutazione finora

- Literary Text - The Lottery TicketDocumento3 pagineLiterary Text - The Lottery TicketRon GruellaNessuna valutazione finora