Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Reynoldsetal Possible Parallels-2

Caricato da

api-2541682760 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

28 visualizzazioni18 pagineTitolo originale

reynoldsetal possible parallels-2

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

28 visualizzazioni18 pagineReynoldsetal Possible Parallels-2

Caricato da

api-254168276Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 18

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

Language Acquisition and Music Acquisition:

Possible Parallels

ALISON M. REYNOLDS

TEMPLE UNIVERSITY, PENNSYLVANIA, USA

SUSI LONG

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA, USA

WENDY H. VALERIO

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA, USA

In this chapter, we use concepts from the field of language and literacy acquisition to

initiate conversation about possible parallels to music and music literacy acquisition.

We suggest such parallels to broaden visions of what it means to acquire music knowl-

edge and skills, and thereby expand possibilities for music teaching and learning. We

present an overview of language acquisition theory, explore parallels between language

acquisition and music acquisition, and provide examples of music acquisition

through music immersion. By using examples from Vygotsky, Cambourne, and others,

we compare the roles of contextualized language interactions and music interactions.

We suggest that adults listen to childrens voices, think of themselves as co-musicers,

and expect young children to begin acquiring music from at least birth. By interact-

ing with children musically, adults can encourage childrens construction of music

thought; and provide truly human ways of knowing, expressing, and interacting. By

doing so, we, as adults, legitimize music as something worth acquiring.

Caregiver: [Turning the page of the picture book] I think I can, I think I can.

Child: [Pointing to the train on the page] Whoo ooo, whoo ooo!

Caregiver: [Joining in] Whoo ooo, whoo oo! Chug a chug a chug a chug

Child: Chug a chug a chug. Rrrrrr [braking sound]. The train stopped!

Caregiver: Stop the train! Rrrrrr. And off it goes up the hill again.

A 3-year-old and an adult interact around a text-picture book, The Little Engine

That Could (Piper, 1976). As they interact with one another and with the text,

they experiment with language and literacy. They do this in the context of a rela-

tionship in which both feel safe enough to draw on what they know as they

move toward what they are coming to know. They bring meaning to the text by

POSSIBLE PARALLELS

A

l

i

s

o

n

M

.

R

e

y

n

o

l

d

s

,

S

u

s

i

L

o

n

g

,

W

e

n

d

y

H

.

V

a

l

e

r

i

o

211

improvising aspects of the storythey point to pictures, make sounds to drama-

tize action, read words, and animate the pictures. They build understandings

from each others contributions and engage one another, going beyond prior

understandings (Lindfors, 1999). Both child and adult are keen observers. The

adult is an astute kidwatcher (Goodman, 1978), learning about the child in the

context of the interaction and using that knowledge to sensitively craft support-

ive feedback. The child draws from prior experiences and blends them with con-

tributions from the text, pictures, and the adult to offer approximations of lan-

guage and literacy. In the safety of the relationship, both take risks that may not

be taken in any other relationship: risks necessary for learning to take place. As a

result, language and literacy teaching and learning potentially occur on many lev-

elsreading as a meaning-making process, letter-sound correspondences, phone-

mic awareness, sentence structure, vocabulary, and story structure.

In this chapter, we use concepts from the field of language and literacy acquisition

to initiate conversation about possible parallels to music and music literacy acquisi-

tion. We suggest such parallels to broaden visions of what it means to acquire music

knowledge and skills and thereby expand possibilities for music teaching and learn-

ing. To accomplish this, the authors present (a) an overview of language acquisition

theory, (b) an exploration of parallels between language acquisition and music acqui-

sition, and (c) examples of music acquisition through music immersion.

The Acquisition of Language: A Theoretical Overview

From the prenatal expectation that children will learn to talk, through the early

years when children approximate language and receive sensitively-crafted feed-

back (Cambourne, 1988), we learn language with the support of others in envi-

ronments conducive to risk-taking. Learners take a chance, give language a try,

use what they know to join interactions and communicate in their worlds. Key

to the acquisition of spoken language is reason to communicate and the opportu-

nity to interact meaningfully with more knowledgeable language users who scaf-

fold the learning process (Bruner, 1983; Vygotsky, 1978). As children interact

with others using language for a variety of functions (Halliday, 1975), they

explore concepts and experiment with language that names those concepts.

Vygotsky (1962) believed that such explorations on a social plane allow learners

to develop understandings that are later relegated to internal thought. More

recent conceptualizers of learning as socially-based see conversational partners

moving fluidly in and out of the roles of novice and expert guiding the participa-

tion and thereby the learning of one another through the interaction (Rogoff,

1990; Wells, 1999). This way, learners share the intentionality and responsibility

for language learning. Engaging others in going beyond current understandings,

children use language to learn language as inquirers within and beyond their

worlds (Halliday, 1975; Lindfors, 1999).

POSSIBLE PARALLELS

212

A

l

i

s

o

n

M

.

R

e

y

n

o

l

d

s

,

S

u

s

i

L

o

n

g

,

W

e

n

d

y

H

.

V

a

l

e

r

i

o

Critical to this process of language learning are contextualized demonstrations pro-

vided by conversational partners. Through the interaction, experienced language

users provide demonstrations as they use language in contexts considered to be pur-

poseful and meaningful by the learner (Cambourne, 1988). The learner responds or

initiates communication by approximating language. The more experienced lan-

guage user accepts the learners contributions as meaning-filled (Brown, 1970;

Cambourne, 1988). As the infant coos and babbles, for example, the parent or care-

giver assigns meaning to those sounds and responds accordingly. In this way, chil-

dren learn the art of conversational turn-taking as well as inflection, meaning,

sounds and words, and the facial expressions and gestures that accompany them

(Brown, 1970). This social interactionist perspective also embraces the notion that

form follows function, or that children learn the parts and structures of language

while using it purposefully within meaning-based whole experiences (Halliday,

1975). For example, parents do not typically say to their toddlers, "Were going to

learn about the past tense today," nor do they drill children in the isolated conjuga-

tion of verbs. Instead, as children risk approximations"I goed to Aunt Tanyas yes-

terday"parents (or others) respond sensitively"So, you went to Aunt Tanyas

yesterday?" In the process, children begin to construct rules that explain how lan-

guage is structured and used. Similarly, younger children often use a word or two to

express more complex ideas. For instance, "up" might mean "pick me up."

Conversational partners, using knowledge of situational context (the whole experi-

ence), assign intent and meaning to such telegraphic speech and respond according-

ly"okay, up you go!"thereby providing feedback that allows children to con-

struct further knowledge about language structure (Brown, 1970).

Recent work in the field of language acquisition looks at variations in language

systems in homes and communities and contrasts them with language typically

valued in schools (Delpit, 2002; Heath, 1983; Ladson-Billings, 1994; Nieto,

1999; Taylor & Dorsey-Gaines, 1988). These studies help to erase an older

deficit perspective that privileges language used in White, middle class, English-

speaking environments over other uses of language: they illuminate the impor-

tance of recognizing and valuing multiple ways of learning, knowing, and

expressing. Implications for educators include the responsibility to broaden the

norm of what is recognized as language to include multiple ways of knowing,

expressing, and interacting. These studies guide us to value what children and

families know as we (a) create opportunities for children to connect further

learning to existing knowledge, and (b) expand the world views of all children by

legitimatizing diverse language and literacy use.

The Acquisition of Music: Possible Parallels to Language Acquisition

As authors we make no claims that music is a language, or that music represents

the same types of thoughts as does language. But humans use music to commu-

POSSIBLE PARALLELS

A

l

i

s

o

n

M

.

R

e

y

n

o

l

d

s

,

S

u

s

i

L

o

n

g

,

W

e

n

d

y

H

.

V

a

l

e

r

i

o

213

nicate (Bernstein, 1976; Papousek, 1996; Woodward, 2005). Although music

may allow humans to evoke or conjure up emotions, the pitches and rhythms

that are the essentials of music do not, and probably will never, represent the

same types of concrete or abstract thoughts represented by language. Music rep-

resents its own type of thought: abstract, untouchable, and essentially human.

Nonetheless, to be a musicer (Elliott, 1995)one who makes musicis the

birthright of each human. Most researchers agree that humans are born with the

potential to music (Clarke, 1989; Gardner, 1993; Gordon, 2003a, 2003b;

McAdams, 1987). With that knowledge, ponder the next set of questions.

Though adults expect that most young children will learn to talk, do they expect that

young children will learn to music? Do adults expect children and themselves to have

reason to communicate using music? Do children approximate musicconstruct

musical understandings and initiate music-based interactions? If so, how do adults rec-

ognize them? What constitutes adults sensitively crafted, music feedback? What is

risk-taking in a music-learning environment? Do adults facilitate risk-taking for chil-

drens music-learning? What motivates young children to music, and what kinds of

opportunities help them learn to music? How do childrens music explorations allow

them to develop music understandings that they can later relegate to internal thought?

Do adults consider children as conversational partners in music who can, like them-

selves, move fluidly in and out of the roles of novice and expert as they guide one

another during their interactions?

We ask those many questions in direct parallel to what is understood about language

acquisition. Although musicians, music philosophers, historians, researchers, and prac-

titioners

1

have considered aspects of music learning in relation to aspects of language

learning, we realize that less is understood about how young children acquire music

than how young children acquire language. We propose that, by approaching music as

a symbol system that may be acquired aurally, orally, visually, and kinesthetically, adults

can listen to childrens voices for ways in which they music. Adults can interact musi-

cally with them to invite, entice, and encourage young children to claim their music

learning potentials as they participate as co-constructers of music knowledge and skills.

In turn, adults may gain knowledge about the nature of music development, and may

formulate strategies and practices to enhance human music acquisition. As they do so,

adults may realize that children come ready to make and participate in music from

birth, if not in utero.

Do we value what children bring to the learning table? In other words, if recent lan-

guage research points out the diversity of legitimate uses of language and literacy in

homes and communities previously not acknowledged or valued in schools, how can

we do the same as we consider the acquisition of musical knowledge? How can

we begin by honoring what children know and build on that knowledge; thereby

broadening the vision of what is considered to be the norm in music?

POSSIBLE PARALLELS

214

A

l

i

s

o

n

M

.

R

e

y

n

o

l

d

s

,

S

u

s

i

L

o

n

g

,

W

e

n

d

y

H

.

V

a

l

e

r

i

o

Emergent Literacy: We Emerge as Literate From Birth

According to an emergent literacy perspective, human beings emerge as literate

from birth (Clay, 1979; Holdaway, 1984; Ferreiro & Teberosky, 1996). The

infant reads the smile on his mothers face, the toddler calls out at the sign for a

favorite restaurant, the preschooler interprets her scribbles as a letter to Auntie,

and the child reads the pictures in The Little Engine That Could (Piper, 1976). In

contrast to a readiness perspective that suggests that children must acquire specif-

ic skills before they can learn to read and write, an emergent literacy perspective

sees children learning skills while they are engaged in the act of using spoken and

written language. Teachers who embrace such a view build from what children

know rather than what they do not know. From an emergent literacy perspective,

educators see themselves not as teachers of reading and writing but as those who

guide readers and writers.

Just as with learning spoken language, we learn literacy as we use it for a variety

of functions, such as learning to gather and share information, to ask why, to reg-

ulate behavior, to interact, to tell about self, to imagine, and to request (Halliday,

1975). In other words, we do not learn to speak, read, and write merely through

imitating language and literacycopying sentences from the board, filling out

worksheets, memorizing vocabulary words. Children construct understandings of

language and literacy as they make approximations in purposeful contexts and

engage with others in ways that invite feedback that moves them forward

(Cambourne, 1988; Lindfors, 1999). They initiate topics of conversation, engage

with others using language, and transact with and think critically about texts

they read or conversations in which they participate.

Cambourne (1988) suggests that specific conditions allow such learning to take

place. We learn to speak, read, and write when we are immersed in a regular

flood of meaningful language and literacy around us; when we receive thousands

of demonstrations of real language and literacy use; when those around us expect

that we will speak, read, and write; when we have plenty of opportunities to

employ/use language and literacy for purposes meaningful to us; when we are

applauded for our approximations and provided sensitive feedback that moves us

forward; and when we are allowed to take responsibility for our own learning. In

other words, children engage as inquirers working to make sense of the world

around them using language and literacy in functional contexts while learning

both (Mills, OKeefe, & Jennings, 2004; Short, Harste, & Burke, 1996).

Would there be general agreement that humans are born musically literate? The

answer to that surely depends upon the extent to which ones definition of music

literacy is anchored solely to the abilities to read and write music notationthe

symbol system that parallels text for a language. A comprehensive definition of

POSSIBLE PARALLELS

A

l

i

s

o

n

M

.

R

e

y

n

o

l

d

s

,

S

u

s

i

L

o

n

g

,

W

e

n

d

y

H

.

V

a

l

e

r

i

o

215

music literacy necessarily would acknowledge a musicers engagement in music inter-

actions beyond those focused solely on reading music notation. To consider nurturing

music literacy as the opportunity to nurture a culture of independent musicers who

are music listeners, music speakers, music readers and music writers would value young

children as music doers and thinkers from birth. Certainly, most very young children

do not have reasons and opportunities to access music notation from birth that paral-

lel those for accessing text or pictures. Instead, their earliest reasons and opportunities

to music parallel the aural, oral, kinesthetic, gestural (physically expressive), and non-

text visual components of learning to interact using language during conversations.

What are signs of emergent music literacy? Essentially, much about young childrens

aural and oral engagement suggests that they music from birth (Blacking, 1976;

Papousek, 1996; Tafuri & Donatella, 2002), if not in utero. Signs that are more

directly parallel to language examples could include the infant who reads the smile

on his mothers face as she sings a lullaby, the toddler who either sings out or calls

out for a favorite music recording, and the child who improvises singing while lis-

tening to a familiar tune. Parents might be fostering young childrens emergent

music literacy as they initiate interactions with them using music. We know that

parents and caregivers initiate music interactions because they enjoy the social activi-

ty with their children (Jorgensen, 1997; North, Hargreaves, &Tarrant, 2002;

Papousek, 1996). Those music interactions might also foster childrens spontaneous

music approximations (Burton, 2002; Papousek, 1996) that may be interpreted

signs of emergent music literacy.

Infants and young children music in a variety of ways: aurally, orally, and kinestheti-

cally. Researchers have documented childrens (a) responses to a variety of music

stimuli (Moog, 1976), (b) one-on-one music interactions (Kelley & Sutton-Smith,

1987; McKeron, 1979; Papousek & Papousek, 1981; Tafuri & Donatella, 2002),

(c) movement as a response to music (Miller, 1986; Metz, 1986; Reynolds, 1995;

Sims, 1985), and (d) spontaneous music approximations without adult interaction

(Burton, 2002; Moorhead & Pond, 1941). Papousek (1996) recommended that

researchers investigate infants musicing "when being exposed to the complexity of

naturalistic social interactions" (p. 99). As music acquisition researchers, we are grap-

pling with ways to understand indications of young childrens music approxima-

tionstheir vocal and kinesthetic explorations, imitations, and improvisations as

evidence of their emergent music literacy.

We suggest that young childrens music approximations (including physical move-

ment) during music interactions provide initial evidence of their music thinking,

independent of language (Azzara, 2002; Hicks, 1993; Reynolds, 1995, 2005, 2006;

Valerio, Seaman, Yap, Santucci, & Tu, 2006; Woodward, 2005). We can turn to

language and literacy acquisition experts to learn what is understood about the

importance of interactions.

POSSIBLE PARALLELS

216

A

l

i

s

o

n

M

.

R

e

y

n

o

l

d

s

,

S

u

s

i

L

o

n

g

,

W

e

n

d

y

H

.

V

a

l

e

r

i

o

Purposeful Interactions

Vygotskys (1978) work illuminates the power of social interaction in the lives of

learners. Lindfors (1999) writes about Vygotskys notion of zones of proximal

development as places where learners grow by engaging others in going beyond

previous understandings. This concept helps us understand the importance of

constructing learning environments where purposeful interaction is foundational.

Vygotskys ideas, as furthered by Rogoff (1990), help us consider how learners

take on the roles of apprentice/novice and expert within ever-changing zones of

proximal development. Wells (1999) suggests that, within zones of proximal

development, there are no designated teachers. We move in and out of the roles

of apprentice and expert, depending on the schema we bring to each turn in the

conversation. Wells also helps us see that zones of proximal development are not

finite, testable entities. They move and change in amoeba-like fashion as conver-

sational partners change, topics change, and moments change. According to

Wells, within zones of proximal development, every member of the interaction is

both learner and teacher.

Is there a music-equivalent to internal thought in language? Gordon (2003b)

proposes that, through a combination of innate music potential, informal guid-

ance, and formal instruction, each human may audiatehear and comprehend

music for which the sound is no longer (or may never have been) physically pre-

sent. To describe a music learners progressive acquisition of music and music lit-

eracy, he coined the terms preparatory audiation (Gordon, 2003a) and audiation

(Gordon, 2003b).

To think music thoughts or ideasto audiatewe interact with musics content

(e.g., tonality, meter, style, form) aurally, orally, and kinesthetically. We suggest

that from at least birth, our first coos and gurgles might be interpreted as our

first music approximations. Through purposeful music interactions we move in

and out of the roles of apprentice and expert within the music zones of proximal

development. To audiate, we learn to coordinate our breathing, movement, and

musicing in rich music environments.

Gordon (2003a) recommends establishing music environments rich with a vari-

ety of tonalities, meters, and expressive movements performed by adults for their

children. We extend that recommendation. We suggest that very young children

vocalize approximations that can be interpreted as invitations for music interac-

tions with co-musicers. By listening to childrens voices, immersing them in a

variety of tonalities, meters, and expressive movements, and purposefully inter-

acting with them to create shared music meaning using music syntax, children

and adults may realize their music birthrights. By honoring their music develop-

ment in informal and playful ways, adults can sensitively guide childrens progres-

POSSIBLE PARALLELS

A

l

i

s

o

n

M

.

R

e

y

n

o

l

d

s

,

S

u

s

i

L

o

n

g

,

W

e

n

d

y

H

.

V

a

l

e

r

i

o

217

sion from exploration to imitation and improvisation as they approximate music

to acquire higher-order music thinking skills.

Music Approximations and Interactions

To examine music acquisition we (Reynolds and Valerio) have been practicing

immersion. Similar to a French immersion class or a German immersion class,

when we enter a music immersion classroom we avoid talking and performing

music with words. Instead, we speak the language we expect to be learned. In

music immersion classes the communication symbol system used for each

immersion session is music. Without trying to teach music concepts, we play

with the dynamic interchange of music ideas through songs, rhythm chants,

tonal patterns, and rhythm patterns, while using silence, imitation and impro-

visation (Reynolds, 2006; Valerio, Seaman, Yap, Santucci, & Tu, 2006). To

emphasize the differences between language and music during music immer-

sion, we use no words while performing songs, rhythm chants, tonal patterns,

and rhythm patterns. Instead, we perform all music using neutral syllables

such as ba, ya, or bum.

2

We often imitate each others music patterns and

improvise music patterns in conversation. We listen to all infant and toddler

vocalizations with the possibility that the children are musicing through bab-

ble (Gordon, 2003a; Holahan, 1987; Moog, 1976). When we hear a childs

vocalization, we either imitate that vocalization, or improvise using tonal pat-

terns or rhythm patterns. When entering a typical childcare situation we per-

form songs, rhythm chants, tonal patterns, and rhythm patterns while moving

around classrooms, playing with the infants, toddlers, and young children. To

a casual observer, it might sound like music time, but it does not look like tra-

ditional circle time-music time.

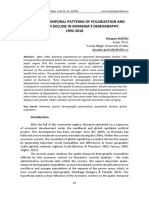

Valerio and another music teacher provided 15-minute music immersion ses-

sions twice-per-week in two different classrooms. Eight infants/toddlers ages

6-months to 18-months were in one classroom, and 10 toddlers ages 18-

months to 36-months were in another classroom. One day, near the end one

of a music immersion session, a 15-month-old toddler who was sitting on the

floor in the middle of the classroom began vocalizing using neutral syllables.

(The teachers had begun the music immersion classes when the toddler was a

10-month-old infant in the same classroom.) The teachers listened to the

childs voice and used imitation and improvisation to incorporate sounds

made by the child into a three-person, interactive jam session. One teacher

also accompanied her vocalizations with patschen. Spontaneously, the group

of musicers co-constructed a musically meaningful conversation similar to the

way two adults might listen to a childs language babble, interpret that babble,

and give meaning to it in a conversation involving the child. Following is a

transcription of that interaction.

POSSIBLE PARALLELS

218

A

l

i

s

o

n

M

.

R

e

y

n

o

l

d

s

,

S

u

s

i

L

o

n

g

,

W

e

n

d

y

H

.

V

a

l

e

r

i

o

Figure 1. Toddler and two music teachers in music interaction (Valerio, 2000b).

By listening to the child, the teachers interpreted her music babble as being tonal (but

not necessarily in a tonality), and being in duple meter. By listening to the child and

by taking music risks, the teachers and toddler engaged as co-musicers in a purposeful

interaction. The teacher provided meaning-filled aural, oral, and physical demonstra-

tion of music use while musicing. Such music interactions are foundational as

musicers develop the aural and oral music vocabularies necessary for eventually giving

meaning to music reading and writing (Gordon, 2003a, 2003b).

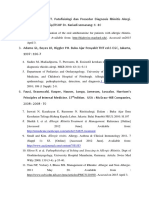

On another day, a music teacher had been singing Down by the Station using

neutral syllables in the toddler classroom. Approximately 15 ft. (5 metres) away

POSSIBLE PARALLELS

A

l

i

s

o

n

M

.

R

e

y

n

o

l

d

s

,

S

u

s

i

L

o

n

g

,

W

e

n

d

y

H

.

V

a

l

e

r

i

o

219

from the teacher, a 21-month-old toddler sat on a pillow, playing with a book.

He turned the pages intently, and seemed to pay no attention to the music

teacher or other children near her. When the music teacher performed a tonal

pattern after singing the song, however, the toddler looked at her, approximated

her tonal pattern, and a tonal pattern interaction ensued. First the toddler began

to approximate the teachers tonal patterns. Then, taking a risk, the teacher began

to approximate the toddlers tonal patterns. The two musicers co-constructed a

music dialogue that began in major tonality, the key of F, and modulated to the

key of G. The co-musicers also began their conversation in duple meter and

modulated to triple meter. Following is a transcription of that music interaction.

Figure 2. Toddler and one music teacher in music interaction (Valerio, 1999).

The entire dialogue was spontaneous, improvised, rich, and musically meaningful

because the two were using music syntax as they realized aural and oral music vocabu-

laries. They knew they had made music in conversation.

POSSIBLE PARALLELS

220

A

l

i

s

o

n

M

.

R

e

y

n

o

l

d

s

,

S

u

s

i

L

o

n

g

,

W

e

n

d

y

H

.

V

a

l

e

r

i

o

In another music immersion class for school-aged children, three girls, ages 5.5, 5.5,

and 9 were sitting in a circle with Valerio and another music teacher. One day, the

teachers decided to see what would happen if the children were asked to improvise a

song. To begin the activity, Valerio said,

Lets make up a group song. Its almost time to go, you guys. Can you

believealready? We havent even played the violins yet! Lets make up our

song and then we will play violin. Here we go [sung as notated]. Ill go, and

then youll go. Just add whatever you want and, when youre finished Annie

3

will start. Be ready to start, Okay? (Valerio, 2000a)

In the notation, notice that the children demonstrate different levels of tonal and

rhythm sophistication. Each child, without ever being formally taught how to, impro-

vised a song, complete with recognizable, consistent tonality, melodic contour, rhythmic

cohesiveness, and phrase structure. None of the teachers or children improvised using

words. By listening to the musicing voices of the children, the teachers learned that the

children were audiating much more about the structure of music than they could have

expected or learned by talking about music. By musicing in a safe environment, the

children and the teachers deepened their music relationship and developed confidence

in their musicianship. Following is a transcription of their music interactions.

Figure 3. Three school-aged children and two music teachers in melodic

improvisation (Valerio, 2000a).

POSSIBLE PARALLELS

A

l

i

s

o

n

M

.

R

e

y

n

o

l

d

s

,

S

u

s

i

L

o

n

g

,

W

e

n

d

y

H

.

V

a

l

e

r

i

o

221

This was the first time the teachers had tried this activity. They were not sure it

would work, and they did not know what the children would do, but they had

spent several weeks cultivating a "safe" music environment. The two younger

girls had been in music immersion classes for the previous four years. The older

girl had joined the music immersion class six weeks previously. The teachers

modeled music risk-taking by improvising. They encouraged the children to take

music risks by asking them "to teach" tonal patterns and rhythm patterns to the

class. If a child taught a pattern to the class, whatever a child sang or chanted was

honored as musicing. The teachers and the other children repeated the pattern

and incorporated it into an improvisation.

In the three music vignettes in this chapter, children approximated music literacy

use because they were comfortable enough and felt validated enough to engage. We

acknowledge thatfor a myriad of reasonsmany adults might view themselves as

less capable musicers than language or literacy users. We ask ourselves, "How this

could be so?" Those who study language acquisition remind us that learning is

grounded in relationships, and when language learners feel that their attempts will

be demeaned or devalued, they stop trying and thereby stop learning. We suggest

that many adults were in settingslikely when they were young childrenwith

adults who accepted limited definitions for what constitutes acceptable musicing.

Shelley (1981) stated, "The influence of the teachers interaction as being the most

crucial to the emergence of the childs innate musicality needs to be investigated" (p.

32). Curricula that support playful, informal learner-centered philosophies through

interactions like those featured in the three music vignettes provide us with a start-

ing point for further research into music interactions.

Summary

What if adults collectively agreed that an infant who listens to an adults lullaby is demon-

strating emergent music literacy? What if we agreed that the cries, coos, and gurgles of

infants are musicing? That is, what if adults assumed that infants want to communicate

using music, attempt to communicate using music, and expect adults to communicate

with themusing music? Specifically, what if we interpreted at least some of the cries, coos,

and gurgles of infants to be initial music approximations rather than language approxima-

tions? Then we could respond to themusing music syntaxnot necessarily with words

offering a type of sensitively crafted music feedback, and engage themin musicing. We

would give music meaning to those sounds, and we could set the stage for music conver-

sations and interactions that, if experienced during the first fewmonths of life in an envi-

ronment safe fromridicule, could shape childrens music learning dispositions, and prepare

themfor participation in more complex music interactions.

With a new mindset that listening and vocal babble and play represent music

approximations rather than language approximations, adults might begin to think of

POSSIBLE PARALLELS

222

A

l

i

s

o

n

M

.

R

e

y

n

o

l

d

s

,

S

u

s

i

L

o

n

g

,

W

e

n

d

y

H

.

V

a

l

e

r

i

o

themselves as co-musicers with children. They would begin to see themselves and

every child as a musicer rather than as musical or unmusical. They would be able to join

music making in moments when a young child spontaneously incorporates singing or

chanting into his play. That is, they would be able to recognize moments when a

young child or several young children spontaneously sing or chantnot because they

occur without the teacher during routine music-making times (like clean up, transi-

tions, or circle time), or other times when childrens initiations of music is recognizable

from music the adults have taught in a traditional manner.

Adults might feel a sense of freedom when they are able to listen to childrens voices

and interpret their sounds as music or language. With practice as conversational music

partners with children, adults could accept what might be childrens invitations to con-

verse in vocal music playwhether or not the childrens music is familiar to them.

Adults who may have never felt comfortable musicing before might risk musicing in

the safety of the relationship with the children. As the children engage adults in impro-

visatory music conversations, they use music in ways that will help them learn music

notation when they first encounter it.

It seems that much about traditional music instructionfrom formalized

childcare to conservatoriesis founded on the premise that a more musically

knowledgeable adult must organize music experiences for the less musically

knowledgeable person. If that is true, much about traditional music instruc-

tion implies a deficit perspective. That is, the experts of traditional music

instruction hold the music truths that they impart to students when they

deem those students to be ready, or talented enough (Kingsbury, 1988) for a

highly valued outcomemusic performance. In the process of fostering a

music education culture based on formal music products (specifically the

imitation of Western European classical music), the music education profes-

sion has limited any former notion of music acquisition to achievement that

comes from training.

If we listen to childrens voices from the earliest days, we can co-construct

music meaning with them. We can view their vocalizations and their move-

ments as emergent music, and support both with contextualized music

demonstrations. We can become childrens conversational music partners and

engage in ways that acknowledge that their contributions are filled with music

meaning. We would agree that they are learning music skills while they are

engaged in the act of approximating music from birth or even earlier. If this

mindset became pervasive, then there would be no need to delay exposure to

music notation. We imagine that teachers would begin to find creative and

meaningful ways to play with music notation from early in childrens lives. By

doing so, perhaps there would be new evidence for the types of parallels

between emergent language literacy and emergent music literacy.

POSSIBLE PARALLELS

A

l

i

s

o

n

M

.

R

e

y

n

o

l

d

s

,

S

u

s

i

L

o

n

g

,

W

e

n

d

y

H

.

V

a

l

e

r

i

o

223

In the opening vignette, caregiver and child enjoy moments together as language

and literacy learners. The caregiver engages the child in meaningful demonstra-

tions based on real language use. He expects that the child will eventually read

the text, andby providing the child with sensitively crafted feedback that pro-

pels the child forward (back into the text)he floods the child with a moment

that is (surely) only one among thousands of such moments. The opportunities

to use language to learn language are bountiful in nearly limitless varieties of

interactions. Because the caregiver allows the child to initiate topics of conversa-

tion, to request play, and to ask questions, the child can take responsibility for

his learning. The cycle continues when the caregiver listens to the childs voice

and furthers language and literacy interaction.

In the music vignettes in this chapter, adults and children interact to promote

music acquisition in ways that we propose parallel language acquisition. In other

ways, the interactions do not parallel language acquisition: (a) the musicers are

not using words with the music to motivate one anothers engagement, (b) the

conditions for music "conversations" allow for two or more musicers to music

simultaneously and still be heard and understood, and (c) childrens emergent

music literacy has not included early interaction with notation in the way that

their emergent language literacy has included text and pictures.

For children to acquire language and literacy, Cambourne (1988) suggests that spe-

cific conditions allow learning to take place. Those conditionsadapted for music

learning and literacycan support adults decisions to listen to childrens voices as

musical voices: we immerse children in a regular flood of meaningful music and

music literacy; provide thousands of demonstrations of musicing in contexts chil-

dren consider meaningful; expect that children emerge as musically literate; allow

learner-centered opportunities for children to employ music and music literacy for

purposes meaningful to them; applaud their music approximations, and provide

sensitively crafted feedback to move their musicing forward. Finally, by choosing at

times to refrain from being the music providerby listening in supportive silence

(Hicks, 1993; Reynolds, 1995, 2006; Valerio et al., 1998; Valerio et al., 2006)

we can allow children to be responsible for their own music learning.

As adults, we have a responsibility to listen to childrens voices, expect them to be

full of music possibilities, and encourage childrens construction of music thought.

By encouraging their music thought, we provide truly human ways of knowing,

expressing, and interacting, and we legitimize music as something worth acquiring.

References

Aiello, R. (1994). Music and language: Parallels and contrasts. In R. Aiello & J. Sloboda (Eds.), Musical perceptions

(pp. 4063). New York: Oxford University Press.

Azzara, C. D. (2002). Improvisation. In R. Colwell & C. Richardson (Eds.), The new handbook of research on music

teaching and learning (pp. 171187). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

POSSIBLE PARALLELS

224

A

l

i

s

o

n

M

.

R

e

y

n

o

l

d

s

,

S

u

s

i

L

o

n

g

,

W

e

n

d

y

H

.

V

a

l

e

r

i

o

Bernstein, L. (1976). The unanswered question: Six talks at Harvard. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Besson, M., & Schn, D. (2003). Comparison between language and music. In I. Peretz & R. Zatorre (Eds.), The

cognitive neuroscience of music (pp. 269293). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Blackburn, L. (1998). Whole music: A whole language approach to teaching music. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Blacking, J. (1976). How musical is man? London: Faber.

Brown, R. (1970). Three processes in the childs acquisition of syntax: The childs grammar from I to III. In R.

Brown (Ed.), Psycholinguistics: Selected papers by Roger Brown. New York: MacMillan.

Bruner, J. (1983). A childs talk: Learning to use language. New York: Horton.

Burton, S. (2002, August). An exploration of preschool childrens spontaneous songs and chants. Visions of Research

in Music Education, 2(Special Edition), 716. Retrieved March 9, 2005,

from http://www.rider.edu/~vrme/articles2/vrme.pdf

Cambourne, B. (1988). The whole story: Natural learning and the acquisition of language. Auckland, NZ: Scholastic.

Chen-Haftek, L. (1997). Music and language development in early childhood: Integrating past and present research

in the two domains. Early Child Development and Care, 130, 8597.

Clarke, E. F. (1989). Issues in language and music. Contemporary Music Review, 4, 922.

Clay, M. (1979). Reading: The patterning of complex behaviour. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Delpit, L. (2002). The skin that we speak: Thoughts on language and culture. New York: The New Press.

DeWitt, L., & Samuel, A. (1990). The role of knowledge-based expectations in music perception: Evidence from

musical restoration. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 119(2), 12344.

Elliott, D. J. (1995). Music matters. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ferreiro, E., & Teberosky, A. (1996). Literacy before schooling. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Gardner, H. (1973). The arts and human development. New York: Wiley.

Gardner, H. (1993). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York: Basic Books.

Goodman, Y. (1978). Kidwatching: An alternative to testing. National Elementary Principal, 57, 4145.

Gordon, E. E. (2003a). Learning sequences in music: Skill, content, and patterns. Chicago: GIA.

Gordon, E. E. (2003b). A music learning theory for newborn and young children (Rev. ed.). Chicago: GIA.

Gruhn, W. (2005). Understanding musical understanding. In D. J. Elliott (Ed.), Praxial music education (pp.

98111). New York: Oxford University Press.

Halliday, M. K. (1975). Learning how to mean: Explorations in the development of language. London: Edward Arnold.

Heath, S. B. (1983). Ways with words: Language, life, and work in communities and classrooms. Cambridge, England:

Cambridge University Press.

Holdaway, D. (1984). Foundations of literacy. New South Wales, Australia: Ashton Scholastic.

Holahan, J. M. (1987). Toward a theory of music syntax: Some observations of music babble in young children. In

J. C. Peery, I. W. Peery, &T. W. Draper (Eds.), Music and child development (pp. 96106). New York: Springer-Verlag.

Hicks, W. (1993). An investigation of the initial stages of preparatory audiation (Doctoral dissertation, Temple

University, 1993). Dissertation Abstracts International, 5404A, 1277.

Imberty, M. (1996). Linguistic and musical development in preschool and school-age children. In I. Delige & J.

Sloboda (Eds.), Musical beginnings: Origins and development of musical competence (pp. 191213). Oxford,

England: Oxford University Press.

Jorgensen, E. R. (1997). In search of music education. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Kelley, L., & Sutton-Smith, B. (1987). A study of infant musical productivity. In J. C. Peery, I. W. Peery, & T. W.

Draper (Eds.), Music and child development (pp. 3553). New York: Springer-Verlag.

Kingsbury, H. (1988). Music, talent, and performance: A conservatory cultural system. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1994). The dreamkeepers: Successful teachers of African-American children. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Langer, S. (1956). Philosophy in a new key (3rd ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lerdahl, F., & Jackendoff, R. (1983). A generative theory of tonal music. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Lindfors, J. (1999). Childrens inquiry: Using language to make sense of the world. Urbana, IL: NCTE.

Locke, S., & Kellar, L. (1973). Categorical perception in a non-linguistic mode. Cortex, 9, 355369.

McAdams, S. (1987). Music: A science of the mind? Contemporary Music Review, 2, 161.

McKeron, P. E. (1979). The development of first songs in young children. In H. Gardner & D. Wolf (Eds.), Early

symbolization: New directions for child development, Vol. 3 (pp. 1726). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Metz, E. (1986). Movement as a musical response among preschool children (Doctoral dissertation, Arizona State

University, 1986). Dissertation Abstracts International, 47, 3691.

Miller, L. (1986). A description of childrens musical behavior: Naturalistic. Journal of Research in Music Education, 87, 117.

Mills, H., OKeefe, T., & Jennings, L. (2004). Listening carefully and looking closely. Urbana, IL: NCTE.

Moog, H. (1976). The musical experience of the pre-school child (C. Clarke, Trans.). London: Schott Music.

Moorhead, G. E., & Pond, D. (1941). Music of young children. Santa Barbara, CA: Pillsbury Foundation for the

Advancement of Music Education.

Nieto, S. (1999). The light in their eyes: Creating multicultural learning communities. New York: Teachers College Press.

North, A. C., Hargreaves, D. J., & Tarrant, M. (2002). Social psychology and music education. In R. Colwell & C.

Richardson (Eds.), The new handbook of research on music teaching and learning (pp. 604625). Oxford, England:

Oxford University Press.

POSSIBLE PARALLELS

A

l

i

s

o

n

M

.

R

e

y

n

o

l

d

s

,

S

u

s

i

L

o

n

g

,

W

e

n

d

y

H

.

V

a

l

e

r

i

o

225

Papousek, H. (1996). Intuitive parenting: A hidden source of musical stimulation in infancy. In I. Deliege & J.

Sloboda (Eds.), Musical beginnings: Origins and development of musical competence (pp. 88112). New York:

Oxford University Press.

Papousek, M., & Papousek, H. (1981). Musical elements in the infants vocalizations: Their significance for

communication, cognition and creativity. In L. P. Lipsitt (Ed.), Advances in infancy research, Vol. 1 (pp.

163224). Norwood, NJ: Albex.

Philpott, C. (2001). Is music a language? In C. Philpott & C. Plummeridge (Eds.), Issues in music teaching (pp.

3246). London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Piper, W. (1976). The little engine that could. New York: Platt & Munk.

Reynolds, A. M. (1995). An investigation of the movement responses performed by children 18 months to three years of

age and their caregivers to rhythm chants in duple and triple meters (Doctoral dissertation, Temple University,

1995). Dissertation Abstracts International, 5604A, 1283.

Reynolds, A. M. (2005). Guiding early childhood music development: A moving experience. In M. Runfola & C.

Taggart (Eds.), The development and practical application of Music Learning Theory (pp. 87100). Chicago: GIA.

Reynolds, A. M. (2006, Spring). Vocal interactions during informal early childhood music classes. Bulletin of the

Council for Research in Music Education 168, 116.

Rogoff, B. (1990). Apprenticeship in thinking: Cognitive development in social context. Oxford, England: Oxford

University Press.

Sachs, C. (1943). The rise of music in the ancient world. New York: Norton.

Shelley, S. (1981). Investigating the musical capabilities of young children. Bulletin of the Council for Research in

Music Education, 68, 116.

Short, K., Harste, J., & Burke, C. (1996). Creating classrooms for authors and inquirers. Portsmouth, NH:

Heinemann.

Sims, W.L (1985). Young childrens creative movement to music: Categories of movement, rhythmic characteristics,

and reactions to changes. Contributions to Music Education, 12, 42-50.

Sloboda, J. A. (1985). The musical mind. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Sloboda, J. A. (2005). Exploring the musical mind: Cognition, emotion, ability, function. Oxford, England: Oxford

University Press.

Suzuki, S. (1969). Nurtured by love: The classic approach to Talent Education (W. Suzuki, Trans.). New York:

Exposition Press.

Tafuri, J., & Donatella, V. (2002). Musical elements in the vocalizations of infants aged 2-8 months. British Journal

of Music Education, 19, 7378.

Taggart, C. C., Bolton, B. M., Reynolds, A. M., Valerio, W. H., & Gordon, E. E. (2000). Jump right in: The music

curriculum Book 1 (Rev. ed.). Chicago: GIA.

Taggart, C. C., Bolton, B. M., Reynolds, A. M., Valerio, W. H., & Gordon, E. E. (2001). Jump right in: The music

curriculum Book 2 (Rev. ed.). Chicago: GIA.

Taggart, C. C., Bolton, B. M., Reynolds, A. M., Valerio, W. H., & Gordon, E. E. (2004). Jump right in: The music

curriculum Book 3 (Rev. ed.). Chicago: GIA.

Taggart, C. C., Bolton, B. M., Reynolds, A. M., Valerio, W. H., & Gordon, E. E. (2006). Jump right in: The music

curriculum Book 4 (Rev. ed.). Chicago: GIA.

Tan, N., Aiello, R., & Bever, T. G. (1985). Harmonic structure as a determinant of melodic organization. Memory

and Cognition, 9, 533539.

Taylor, D., & Dorsey-Gaines, C. (1988). Growing up literate: Learning from inner city families. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Valerio, W. H. (1999). [Toddler and one music teacher in music interaction]. Unpublished raw data.

Valerio, W. H. (2000a). [Three school-aged children and two music teachers in melodic improvisation].

Unpublished raw data.

Valerio, W. H. (2000b). [Toddler and two music teachers in music interaction]. Unpublished raw data.

Valerio, W. H. (2005). A music acquisition research agenda for Music Learning Theory. In C. Taggart & M. Runfola

(Eds.), The development and practical application of Music Learning Theory (pp. 104113), Chicago: GIA.

Valerio, W. H., Reynolds, A. M., Bolton, B. M., Taggart, C. C., & Gordon, E. E. (1998). Music play: Guide for

parents, teachers and caregivers. Chicago: GIA.

Valerio, W. H., Reynolds, A. M., Bolton, B. M., Taggart, C. C., & Gordon, E. E. (2002). Music play. (H. K. Yi,

Trans.). Hanam-city, Korea: IEC Music English.

Valerio, W. H., Reynolds, A. M., Bolton, B. M., Taggart, C. C., & Gordon, E. E. (2004a). Muzikos zaismas

[Music play] (R. Proskute-Grun, Trans). Vilnius, Lithuania: Kronta.

Valerio, W. H., Reynolds, A. M., Bolton, B. M., Taggart, C. C., & Gordon, E. E. (2004b). Yinyue youxi [Music

play] (G. Wang & H. Liu, Trans). Beijing: China Translation and Publishing Corporation.

Valerio, W. H., Seaman, M. A., Yap, C. C., Santucci, P. M., & Tu, M. (2006, Fall). Vocal evidence of toddler music

syntax acquisition: A case study. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 170, 3346.

Vygotsky, L. (1962). Thought and language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

POSSIBLE PARALLELS

226

A

l

i

s

o

n

M

.

R

e

y

n

o

l

d

s

,

S

u

s

i

L

o

n

g

,

W

e

n

d

y

H

.

V

a

l

e

r

i

o

Wells, G. (1999). Dialogic inquiry: Toward a sociocultural practice and theory of education. Cambridge, England:

Cambridge University Press.

Woodward, S. C. (2005). Critical matters in early childhood music education. In D. J. Elliott (Ed.), Praxial music

education: Reflections and dialogues (pp. 249266). New York: Oxford University Press.

1

Including Aiello, 1994; Azzara, 2002; Bernstein, 1976; Besson & Schn, 2003; Blackburn, 1998; Chen-Haftek,

1991; Clarke, 1989; De Witt & Samuel, 1990; Gardner, 1973; Gordon, 2003a, 2003b; Gruhn, 2005; Imberty,

1996; Kelly & Sutton-Smith, 1987; Langer, 1956; Lerdahl & Jackendoff, 1983; Locke & Kellar, 1973; McAdams,

1987; Philpott, 2001; Reynolds, 2006; Sachs, 1943; Sloboda, 1985, 2005; Suzuki, 1969; Taggart, Bolton, Reynolds,

Valerio, & Gordon, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2004, 2006; Tan, Aiello, & Bever, 1985; Valerio, 2005; Valerio, Reynolds,

Bolton, & Taggart, Gordon, 1998, 2002, 2004a, 2004b; Valerio, Seaman, Yap, Santucci, & Tu, 2006.

2

All nonsense syllables are notated using the International Phonetic Alphabet.

3

Pseudonym.

POSSIBLE PARALLELS

A

l

i

s

o

n

M

.

R

e

y

n

o

l

d

s

,

S

u

s

i

L

o

n

g

,

W

e

n

d

y

H

.

V

a

l

e

r

i

o

227

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

The Use of Silence in Eliciting Student Responses

in Early Childhood Music Classes

CHRISTINA M. HORNBACH

HOPE COLLEGE, HOLLAND, MICHIGAN, USA

In this chapter, I discuss the importance of silence as a mechanism for eliciting stu-

dent responses in early childhood music classes. First, I include a brief discussion of

early childhood music development (preparatory audiation), early childhood music

classes, developmentally appropriate practice (play), and then focus on the importance

of eliciting student responses and silence (wait time) in the context of teaching. I also

introduce and discuss the concept of the interactive response chain, as it relates to

silence and play. Specific teaching situations illustrate silence, eliciting student

responses, and the interactive response chain with young children.

Introduction

During the first year of a childs life, the neural synapses of the brain are connect-

ing in ways that establish lifelong cognitive processing patterns (Cohen, 2002).

As a result, brain development during early childhood plays an important role in

how human beings cognitively process music throughout life (Gordon, 2003b).

With a stimulating musical environment, young children develop neural net-

works that enhance their potential (musical aptitude) for future musical under-

standing and growth. This clearly points to the need for appropriate music envi-

ronments for children in their first year of life.

Very young children learn music in much the same way that they learn a lan-

guage. In order to learn to speak, children informally listen to language being

spoken in their environments; this language learning even begins in the womb, as

hearing is fully developed by the end of the first trimester. Children babble and

eventually learn to speak after listening to the language in their environment.

With music, children must listen to the sounds and syntax of the musical cul-

ture; eventually, they experiment with producing musical sounds, which is musi-

cal babble (Gordon, 2003b).

Some children may not be exposed to as rich an environment musically as they

are linguistically, as some parents may not feel comfortable singing or moving to

music in a rhythmic way (Taggart, 2003). Because of this and a desire to provide

ELICITING STUDENT RESPONSES

228

C

h

r

i

s

t

i

n

a

M

.

H

o

r

n

b

a

c

h

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Project Proposal - Hospital Management SystemDocumento20 pagineProject Proposal - Hospital Management SystemDilanka Liyanage95% (19)

- Structural Analysis Cheat SheetDocumento5 pagineStructural Analysis Cheat SheetByram Jennings100% (1)

- Exploring KodalyDocumento46 pagineExploring Kodalyapi-2541682760% (1)

- Developmentally Appropriate PracticeDocumento32 pagineDevelopmentally Appropriate Practiceapi-254438601100% (2)

- Lesson 2 Cultural Relativism - Part 1 (Reaction Paper)Documento2 pagineLesson 2 Cultural Relativism - Part 1 (Reaction Paper)Bai Zaida Abid100% (1)

- PaartsstandardsDocumento15 paginePaartsstandardsapi-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- LessonplanintroDocumento2 pagineLessonplanintroapi-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- k-12 GuidelinesDocumento26 paginek-12 Guidelinesapi-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- 430 FinalDocumento6 pagine430 Finalapi-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- Field Work CompetenciesDocumento17 pagineField Work Competenciesapi-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- MLD InterviewDocumento1 paginaMLD Interviewapi-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- General Music Today-2012-Anderson-27-33Documento8 pagineGeneral Music Today-2012-Anderson-27-33api-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- Waters Sut Mldorffppt2 2 29 13Documento15 pagineWaters Sut Mldorffppt2 2 29 13api-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- General Music Today-2002-Westervelt-13-91Documento8 pagineGeneral Music Today-2002-Westervelt-13-91api-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- General Music Today-2002-Westervelt-13-91Documento8 pagineGeneral Music Today-2002-Westervelt-13-91api-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- Goin To BostonDocumento1 paginaGoin To Bostonapi-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sut MLD Waterspresentation 2 27 131Documento17 pagineSut MLD Waterspresentation 2 27 131api-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- WeikertDocumento12 pagineWeikertapi-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Noble Duke of YorkDocumento1 paginaThe Noble Duke of Yorkapi-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- 6reynolds Tempo Musical Moments Reprint-2Documento2 pagine6reynolds Tempo Musical Moments Reprint-2api-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- Orff Instruments GuidelinesDocumento3 pagineOrff Instruments Guidelinesapi-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- MLD Music Education Beginnings1-3Documento22 pagineMLD Music Education Beginnings1-3api-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- TrehuboriginsDocumento5 pagineTrehuboriginsapi-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Bear Went Over The MountainDocumento1 paginaThe Bear Went Over The Mountainapi-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- Alabama GalDocumento1 paginaAlabama Galapi-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- Riding in A BuggyDocumento1 paginaRiding in A Buggyapi-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- ParentsDocumento11 pagineParentsapi-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- Shoo FlyDocumento1 paginaShoo Flyapi-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- Verbal Association Triple Rhythm PatternsDocumento1 paginaVerbal Association Triple Rhythm Patternsapi-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- Aural-Oral 23 Note Patterns-2Documento1 paginaAural-Oral 23 Note Patterns-2api-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- Verbal Association 23 Note PatternsDocumento1 paginaVerbal Association 23 Note Patternsapi-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- Verbal Association Triple Rhythm PatternsDocumento1 paginaVerbal Association Triple Rhythm Patternsapi-254168276Nessuna valutazione finora

- Education Is The Foundation For Women Empowerment in IndiaDocumento111 pagineEducation Is The Foundation For Women Empowerment in IndiaAmit Kumar ChoudharyNessuna valutazione finora

- Exercises 2Documento7 pagineExercises 2Taseen Junnat SeenNessuna valutazione finora

- IIT JEE Maths Mains 2000Documento3 pagineIIT JEE Maths Mains 2000Ayush SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- 4.5 Roces v. HRETDocumento1 pagina4.5 Roces v. HRETZepht Badilla100% (1)

- Las Grade 7Documento16 pagineLas Grade 7Badeth Ablao67% (3)

- Haiti Research Project 2021Documento3 pagineHaiti Research Project 2021api-518908670Nessuna valutazione finora

- Mercado Vs Manzano Case DigestDocumento3 pagineMercado Vs Manzano Case DigestalexparungoNessuna valutazione finora

- Essay On NumbersDocumento1 paginaEssay On NumbersTasneem C BalindongNessuna valutazione finora

- O Level Physics QuestionsDocumento9 pagineO Level Physics QuestionsMichael Leung67% (3)

- Contract ManagementDocumento26 pagineContract ManagementGK TiwariNessuna valutazione finora

- 3 - QMT425-T3 Linear Programming (29-74)Documento46 pagine3 - QMT425-T3 Linear Programming (29-74)Ashraf RadzaliNessuna valutazione finora

- Gutoiu - 2019 - Demography RomaniaDocumento18 pagineGutoiu - 2019 - Demography RomaniaDomnProfessorNessuna valutazione finora

- தசம பின்னம் ஆண்டு 4Documento22 pagineதசம பின்னம் ஆண்டு 4Jessica BarnesNessuna valutazione finora

- Opinion - : How Progressives Lost The 'Woke' Narrative - and What They Can Do To Reclaim It From The Right-WingDocumento4 pagineOpinion - : How Progressives Lost The 'Woke' Narrative - and What They Can Do To Reclaim It From The Right-WingsiesmannNessuna valutazione finora

- 13 19 PBDocumento183 pagine13 19 PBmaxim reinerNessuna valutazione finora

- Delhi Public School, Agra: The HolocaustDocumento3 pagineDelhi Public School, Agra: The Holocaustkrish kanteNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Digest 1-4.46Documento4 pagineCase Digest 1-4.46jobelle barcellanoNessuna valutazione finora

- Mendezona vs. OzamizDocumento2 pagineMendezona vs. OzamizAlexis Von TeNessuna valutazione finora

- Bi Tahun 5 Penjajaran RPT 2020Documento6 pagineBi Tahun 5 Penjajaran RPT 2020poppy_90Nessuna valutazione finora

- Grandinetti - Document No. 3Documento16 pagineGrandinetti - Document No. 3Justia.comNessuna valutazione finora

- Principles of Learning: FS2 Field StudyDocumento8 paginePrinciples of Learning: FS2 Field StudyKel Li0% (1)

- ViShNu-Virachita Rudra StotramDocumento6 pagineViShNu-Virachita Rudra StotramBhadraKaaliNessuna valutazione finora

- Why Is "Being Religious Interreligiously" Imperative For Us Today?Documento1 paginaWhy Is "Being Religious Interreligiously" Imperative For Us Today?Lex HenonNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter-1-Operations and Management: There Are Four Main Reasons Why We Study OM 1)Documento3 pagineChapter-1-Operations and Management: There Are Four Main Reasons Why We Study OM 1)Karthik SaiNessuna valutazione finora

- 19 March 2018 CcmaDocumento4 pagine19 March 2018 Ccmabronnaf80Nessuna valutazione finora

- © The Registrar, Panjab University Chandigarh All Rights ReservedDocumento99 pagine© The Registrar, Panjab University Chandigarh All Rights Reservedshub_88Nessuna valutazione finora

- DapusDocumento2 pagineDapusIneke PutriNessuna valutazione finora