Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Tomoko Hidaka Salaryman Masculinity 2010

Caricato da

Anonymous Z4yz4JWKqF100%(1)Il 100% ha trovato utile questo documento (1 voto)

662 visualizzazioni239 pagineSalaryman masculinity : the continuity of and change in the Hegemonic Masculinity in Japan / by Tomoko Hidaka. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted without prior written permission from the publisher.

Descrizione originale:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoSalaryman masculinity : the continuity of and change in the Hegemonic Masculinity in Japan / by Tomoko Hidaka. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted without prior written permission from the publisher.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

100%(1)Il 100% ha trovato utile questo documento (1 voto)

662 visualizzazioni239 pagineTomoko Hidaka Salaryman Masculinity 2010

Caricato da

Anonymous Z4yz4JWKqFSalaryman masculinity : the continuity of and change in the Hegemonic Masculinity in Japan / by Tomoko Hidaka. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted without prior written permission from the publisher.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 239

Salaryman Masculinity

Social Sciences in Asia

Edited by

Vineeta Sinha

Syed Farid Alatas

Chan Kwok-bun

VOLUME 29

Salaryman Masculinity

Te Continuity of and Change in the

Hegemonic Masculinity in Japan

By

Tomoko Hidaka

LEIDEN BOSTON

2010

Tis book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hidaka, Tomoko.

Salaryman masculinity : the continuity of and change in the hegemonic masculinity

in Japan / by Tomoko Hidaka.

p. cm. (Social sciences in Asia ; v. 29)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-90-04-18303-2 (hardback : alk. paper)

1. MenJapanSocial conditionsCase studies. 2. MenJapanIdentityCase

studies. 3. White collar workersJapanCase studies. 4. MasculinityJapanCase

studies. I. Title. II. Series.

HQ1090.7.J3H54 2010

305.3896220952dc2

2010006224

ISSN 1567-2794

ISBN 978 90 04 18303 2

Copyright 2010 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, Te Netherlands.

Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints BRILL, Hotei Publishing,

IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhof Publishers and VSP.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic,

mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission

from the publisher.

Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by

Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to

Te Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910,

Danvers, MA 01923, USA.

Fees are subject to change.

printed in the netherlands

In memory of my grandmother (19132008) and my father

(19322007)

CONTENTS

Preface .................................................................................................. ix

Notes on the Text ............................................................................... xiii

Introduction ......................................................................................... 1

Chapter One Growing Up: Gendered Experiences in the

Family ............................................................................................... 13

Chapter Two Growing Up: Gendered Experiences in

School ............................................................................................... 43

Chapter Tree Love and Marriage ............................................... 69

Chapter Four Work ......................................................................... 103

Chapter Five Ikigai .......................................................................... 137

Conclusion ........................................................................................... 163

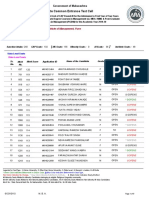

Appendices

Appendix One Biographies of the Participants ..................... 185

Appendix Two Chronological Background of the

Participants ................................................................................. 191

Appendix Tree Tables and Charts ......................................... 193

Bibliography ......................................................................................... 199

Index ..................................................................................................... 219

PREFACE

Why on earth are you interested in masculinity? Tis view, whether

expressed or implied, represents the most typical response to my

research interest in men and masculinities from my friends, acquain-

tances and people I have encountered during my research. In retro-

spect, I realise that my personal interest in Japanese corporate men

and their masculinity has its origins in my work experience in a rela-

tively large trading company in Japan. My work experience dates back

more than a decade when Japanese people frmly believed that Japans

stable economy would last and had not the slightest suspicion that

the bubble economy would burst. Te section to which I was assigned

was engaged in Ofcial Development Assistance (ODA). It was appar-

ent that the men in the section were proud of their jobs, believing

that their projects were facilitating needy countries socio-economic

development. Probably, the fact that the majority of these men wore

a moustache represents an exception to Japanese male white-collar

workers. However, the majority of ruling-class men in recipient coun-

tries, such as India, Nepal and African countries, wore moustaches

and my male colleagues adopted the expedient of wearing a moustache

like government ofcials and project leaders in the recipient countries

as part of their business strategy. Consequently, their assimilation into

the culture of the ruling classes in these countries meant their embodi-

ment, not only of Japanese hegemonic masculinity, but also of the

dominant masculinity of other countries. Perhaps, because of this, in

my eyes, their sense of self as men appeared to be stronger than that

of men in other departments who conducted business mainly with

Japanese clients. It was intriguing that my male colleagues understood,

consciously or unconsciously, the imperfect symbolic aspects of Japa-

nese hegemonic masculinity in other countries (i.e. a well groomed

appearance with no moustache or beard) and adopted the recipient

countries symbolism of dominant masculinity while they knew that

adding moustaches to their presentation did not undermine Japanese

hegemonic masculinity. I was fascinated by their performance of mas-

culinity and the intersection of identity and power.

x preface

In my section, mens duties and womens duties were clearly sepa-

rated, just as Ogasawara (1998) documented in her study of male and

female white-collar workers in a large Japanese company. My inter-

ests in and concerns about gender relations and the way in which my

male colleagues presented themselves lingered in my mind for a long

time. In the meantime, a friend of mine sent me an on-line newspa-

per article about the Japanese mens liberation movement. Learning

about the mens movement in Japan, I was fascinated by the idea of

exploring men and masculinities. It was, perhaps, natural for me to

be intrigued by Japanese corporate men and their masculinity and to

choose them as the topic for my research because my questions about

Japanese salarymen and their masculinity could thus fnd expression

and could fnally be exorcised from my mind. More importantly, I

was convinced that doing research on the masculinity of the Japa-

nese salaryman would contribute to broadening the currently limited

understanding of their masculinity. When I was working in Japan, I

perceived my male colleagues as kigysenshi

1

(corporate warriors), but

now I wonder if this was really so. Kaufman (1994: 142) argues that

power and pain constitute a pair in mens lives and he calls this mens

contradictory experience of power. As will be evident in the following

chapters, contradictions in mens lives emerged in my study.

Tis book draws on my doctoral research as a graduate student at

the University of Adelaide. First and foremost I would like to thank

the supervisors of my doctoral dissertation, Chilla Bulbeck and Shoko

Yoneyama for their invaluable and insightful guidance with regard

to my thesis and for their unstinting support and encouragement

throughout the researching and writing of the manuscript. I was (and

still am) fortunate to have the assistance of these dedicated scholars.

My heartfelt thanks must also go to another mentor, Jennifer Brown,

who was always there for me, for her generous assistance, from reading

my draf and ofering comments on my work to giving me continu-

ing moral support throughout (and even afer) my higher education

in Australia. I am indebted to the participants, who generously gave

their time for my research, for, without their valuable life stories pro-

vided in the interviews I would not have been able to complete my

1

During WWII, the name kigysenshi was conferred on salarymen in contrast

to soldiers who were called industrial warriors (Miyasaka 2002: 4). Te term became

popular again during the high economic growth period.

preface xi

project. I am truly grateful to my family, my relatives and my friends

for their help in fnding the participants. I had the privilege of meeting

Taga Futoshi and Romit Dasgupta. I am grateful for their generous

assistance in giving me useful information and in making their work

available to me. Unexpectedly, Romit became one of my colleagues at

the National University of Singapore. Our recreational activities with

other wonderful colleagues made my new life in Singapore pleasant

without this I would never have been able to take my mind of my

work. My sincere thanks to my colleagues in the discipline of Gender,

Work and Social Inquiry at the University of Adelaide, Ken Bridge,

Jessica Shipman Gunson, Alia Imtoual, George Lewkowicz, Pam

Papadelos, Ros Prosser and Ros Averis for their friendship and moral

support, and Margaret Allen, Kathie Muir, Susan Oakley and Margie

Ripper for their generous scholarly and friendly assistance. I also give

thanks to other colleagues Peter Burns, Gerry Groot and Purnendra

Jain for their assistance and support as well as Glen Staford, Shoo Lin

Siah and other members of CASPAR (Centre for Asian Studies Post-

graduate Academic Review) for their intellectual companionship as

well as friendships. I thank Naomi Hof, Diana Clark, Greg Clark and

his family, Helen and Keith Mitchell (sadly, Keith passed away only

recently), Ivy Wing and her family, Chris Hamilton and his family, Jan

Dash, Jan Miller who is no longer with us, Gus Overall, Libby Ivens

and other friends for their friendship and caring support. Tese friends

made my long and sometimes trying journey to the completion of my

research more meaningful. Finally and surely not least, I would like to

thank my parents, Hidaka Manabu and Kazuko, for their extraordi-

nary generosity and support and my grandmother, Kawamura Fumi,

who raised me with unconditional love. Tis book is dedicated to the

memory of my grandmother and my father who would have rejoiced

unreservedly over my work but unexpectedly departed this life with-

out seeing this book.

NOTES ON THE TEXT

Te names of the participants in this study are fctitious. Japanese full

names mentioned in this thesis are written in the Japanese order, with

family names followed by given names. In the case of the participants

in this study, their names are indicated by family names together with

the Japanese comprehensive courtesy title san (e.g. Amano-san),

which is used to indicate status titles such as Mr., Mrs., Miss, and Ms.

in Japanese.

Te Hepburn style of romanisation is applied in rendering Japanese

words, and macrons indicating long vowelsfor example, as in

rysai kenbo (good wife, wise mother)in order to convey the pro-

nunciation of Japanese words. Tose Japanese words in the Hepburn

style are italicised, as exemplifed in the above example. Tey are inten-

tionally used because of their importance in the Japanese discourse on

sociology, these terms being followed by English translations in brack-

ets. However, macrons are not used for the Japanese words that are

commonly used in Englishfor example, Tokyo.

Quotations from the narratives of the participants in this study as

well as those from publications in Japanese have been translated by

the author.

INTRODUCTION

Tis book concerns Japanese sararman (salarymen) and their mas-

culinities.

1

It focuses on the construction of salaryman masculinities

throughout their lives, exploring three generations of salarymen. In the

Japanese context, in general, employees who receive a monthly salary,

whether company workers or civil servants, call themselves sararman.

In this book, however, sararman specifcally refers to middle-class

white-collar workers who work for a large company. Masculinities are

confgurations of practice structured by gender relations (Connell

1995: 44), and this book draws on Connells gender theory. Te model

of gender structures consists of four dimensions: power relations, pro-

duction relations, emotional relations and symbolic relations (Connell

2002). Power relations refer to patriarchy (the dominance of men

by means of the overall subordination of women) as well as to the

oppression of one group by another (Beasley 1999: 55; Connell 2002:

59; 2000: 24; 1995: 74; 1987: 111; Walby 1990: 20). Production rela-

tions look at the gendered division of labour. Emotional relations

concern sexual and non-sexual emotional attachments to an object,

and symbolic relations signify meanings and symbolsanything

that expresses gender attributes. Masculinities are thus the processes

and practices in the above four facets in relation to femininities and

the efects of these upon individuals physical as well as emotional

experiences, identity and society.

Dasgupta (2005a; 2005b; 2003; 2000) explores hegemonic mascu-

linity i.e. Japanese salaryman masculinity, focusing on the process of

change in hegemonic masculinity through the process of the induction

training for newly hired employees. Taga (2004) also looks at Japanese

transnational corporate men who live in Australia and explores their

experiences in the public sphere as workers and in the private sphere

as husbands (and fathers). Te above literature on Japanese men and

masculinities suggests that the masculine norm in Japan involves

1

One of the important theoretical discoveries is that there is no single masculinity

but multiple masculinities (Brod 1992: 12; Brod and Kaufman 1994: 4; Connell 2000:

10; 1995: 76; Kimmel and Messner 1995: xxi; Segal 1993: 638; but see also Hearn 1996

for an argument about the limitations of the concept of masculinity/masculinities).

2 introduction

heterosexuality and the traditional gendered division of labour, and

this masculine norm is sustained by the power of the company. Yet

changing socio-economic circumstancesfor example recession and

subsequent restructuringhave been undermining the leverage of

the company, and these facts reveal that the masculinity that derives

from the power of the company and the unquestioned normality of

heterosexual marriage and parenting inevitably entails vulnerabil-

ity. Te Japanese masculine norm can be construed as a dependent

masculinity. Nevertheless, despite growing feminism that has gained

strong government support afer the bubble burst, hegemonic mascu-

linity has been challenged less than one might think, as this book will

demonstrate.

Japanese salaryman masculinity is considered to be the dominant or

hegemonic masculinity (Dasgupta 2005a; 2005b; 2003; 2000; Gill 2003;

Ishii-Kuntz 2003; Miller 2003; Roberson 2003; Roberson and Suzuki

2003). Te term hegemonic masculinity does not refer to the most

statistically common type of man but rather to the most desired form in

relation to social, cultural and institutional aspects (Connell 1995: 77;

Connell and Messerschmidt 2005). Japanese salaryman masculinity as

hegemonic has considerable bearing on Japans metamorphosis from

a feudal state to a capitalist nation, founded on the patriarchal hetero-

sexual family together with the state ideology of modernisation that

emerged in the Meiji period (18681912) (Dasgupta 2005a: 69; Uno

1991: 40). Te term sararman (salarymen)

2

laid the foundations of

its orthodoxy in parallel with industrialisation afer the Second World

War (Dasgupta 2000: 193). Te notion of salaryman masculinity as

hegemonic was established in the discourses in the 1950s and 1960s,

creating a distinct division of labour based on a heterosexual com-

plementarity. Just as in advanced nations, rapid industrialisation and

urbanisation in Japan increasingly separated the private from the public

realms, reinforcing divisions between the public sphere as the domain

of men and the private sphere as the domain of women. As the number

of middle-class salarymen (and their housewives) increased, the mat-

rimony of a salaryman and his wife was constructed on the principle

that a man and a woman were perfectly complementary to each other

2

Te use of the word dates back to 1916 when a popular cartoonist published a

series of cartoons about salarymen: the sararman no tengoku; sararman no jigoku

(salarymens heaven; salarymens hell) (Kinmonth 1981: 289).

introduction 3

(Smith 1987: 3). Tat is, the heterosexual breadwinners work hard and

faithfully for their companies, supporting the economic development

of Japan and the well-being of their families, whereas their wives do all

the housekeeping and bear and raise children for the convenience of

patriarchal and industrial capitalism. In this context, hegemonic sala-

ryman masculinity connotes a distinct image of a married man who

embodied the characteristics of being a loyal productive worker, the

primary economic provider for the household, a reproductive husband

and a father.

3

By the mid-1970s, the productive and material power of

salarymens households symbolised the afuence produced by Japans

economic miracle and became the ideal in public discourses. It was

not until the 1990s with the bursting of the economic bubble that the

notion of salarymen came under criticism as a gendered construct

(Dasgupta 2005a: 95).

Despite the clear notion of corporate masculinity as dominant and

hegemonic, substantial empirical research on Japanese salarymen and

their masculinity is still in its infancy. By contrast, research on subor-

dinated and marginalised men in Japan is prolifc (e.g. Lunsing 2002;

2001; McLelland 2005a; 2005b; 2003a; 2003b; 2000; Pfugfelder 1999

for gay men; Gill 2003; Roberson 2003; 1998; Sunaga 1999; Taga 2001

for marginalised men). Tere are a few studies of salarymen in Eng-

lish; however, their focus is limited to one facet of salaryman life and

masculinities. For example, Allison (1994) looks at company-funded

drinking at hostess clubs afer work. Ogasawara (1998) examines

female ofce workers and their relationships with salarymen in a com-

pany, and Vogels ethnographic work depicts salaryman households in

a new residential suburb ([1963] 1971).

In contrast to the above researchers, this book focuses specifcally

on the hegemonic masculinity of Japanese salarymen. It also deals with

three generations of salarymen. Te three-generational approach is a

unique contribution to Japanese masculinity studies, combining what

Bulbeck (1997) revealed in relation to three generations of Australian

women with what Connell (1995) demonstrated with regard to difer-

ent Australian men and masculinities, but following Dasgupta (2005a;

2005b) and Taga (2004) who directed their attention to the research

3

Mackie (2002: 203) argues that the archetypal citizen in the modern Japanese

political system is a male, heterosexual, able-bodied, fertile, white-collar worker. See

also Mackie (2000) and (1995).

4 introduction

arena of Japanese salaryman masculinity. By introducing Japanese

salarymens own accounts of themselves, this book explores the con-

struction of their masculinities throughout their lives. As hegemonic

masculinity is shaped and maintained through the structures of soci-

ety but also changes over time (Connell 1995: 77), the book explores

similarities and diferences across three generations of salarymen

described in these pages as Cohort One, Cohort Two and Cohort

Tree (see below). In addition, similarities and diferences within

each generation are examined. Te life of the three generations covers

the period from before the Pacifc war (from the mid-1920s) through

the post-Pacifc war, the economic miracle (19551973), the burst-

ing of the bubble (the early 1990s) and present debates concerning

Japanese work and family life (see Appendix 2). While these changes

are refected in the participants narratives, little work has been done

which links the changes in interruptions in the performance of mas-

culinity as a result of these dramatic economic and social changes over

the last century. Unlike the above studies of Japanese hegemonic mas-

culinity, the book aims to contribute to creating new knowledge of

cross-generational transformation of Japanese hegemonic masculinity

by applying the inter-generational approach.

Methodology

Te methodology of my research is based on both sociological and

feminist approaches. Tis study adopted in-depth interviews and col-

lected participants life histories as the primary data sourcelife his-

tory here referring to the individuals observations on their past and

present lives in their own terms. Collecting such life histories allows

us to refect not only on personal subjectivity but also on the social

and collective circumstances that shape the lives of the story-tellers

and their changes over time (Anderson and Jack 1991: 11; Chanfrault-

Duchet 1991: 7778; Connell 1995: 89; Plummer 2001: 4; 1983: 14, 70;

Reinharz 1992: 19). Te life history method has its weaknesses, such

as the limited accuracy of memory and the difculty of validating the

narratives told by the interviewees. Te issue of memory is not simply

about an individuals capacity to remember but the fact that memory

is constructed in the process of story-telling. Tis does not mean that

the constructed memory is invalid (Plummer 2001: 238)it has its

own truth because people compose memory to make sense of their

introduction 5

past, whether to generalise or dramatise it or to create a psychologi-

cal distance from it (Allison 2006: 228; Easton 2000; Roseman 2006:

238; Tomson 2006). Tese problems are mitigated in my study by

the socially theorized life history approach which relates interview

materials to prior analysis of the social structure involved (Con-

nell 1992: 739). Accordingly, interview materials are checked against

secondary sources. Te method used to fnd willing participants was

the snowball method: my family, friends and colleagues were asked

to introduce, as research participants, people who met the essential

conditions described below. Tose people that had been introduced

were in turn also asked to introduce their friends or acquaintances for

the research.

One interview was conducted in Perth, Australia, as a pilot inter-

view in May 2004. Tis interviewee had been fred from his job due

to the restructuring of his company and was studying in Australia at

the time of the interview, and the material from this interview was

used in this study. Te remaining interviews were conducted in Japan

in 2004 (in Chiba, Fukuoka, Hygo, Kagoshima,

4

Saitama, Tokyo and

Yokohama). Participants were asked a range of questions as to how

they performed their masculinities in school, how they developed their

sense of themselves as boys and men in their relations in the family

in which they were raised (with their mother, father and siblings) and

how their idea of themselves as men changed, if it did, in their family

of orientation (with their wives and children), at work and so on. In

the process of discussing how these men balanced work and family

commitments, they were asked about how they met their partners, and

their expectations of their partners role in marriage, parenting and

contributing to the household activities and income. Each interview

lasted from one to three hours. Each of the interviews was recorded,

except in four cases where the participants wished not to be tape-

recorded and the researcher took notes instead. Te tape-recorded nar-

ratives of the participants were transcribed by the researcher, retaining

the original Japanese, and all the quotations used throughout this book

were translated from Japanese into English by the author.

4

While Kagoshima represents small-scale economic development, there are locally

developed large banks and branch ofces of major large companies.

6 introduction

Te Men

Te selection criteria were applied to interviews with Japanese white-

collar salarymen who worked or had worked for a large company,

(a large company being defned here as employing more than 1,000

employees). Large corporations were intentionally chosen because

they are socially and culturally the most desired destination for Japa-

nese graduates, as refected in such elements as a higher income, secu-

rity and the existence of in-company welfare. In a sense, the larger

the company for which he works, the more a salaryman conforms

to hegemonic masculinity, and the salarymen interviewed in this

research worked for companies varying in size from approximately

2,000 employees to more than 5,000. Because the proportion of com-

panies which have more than 300 employees accounts for only 0.2 per

cent of the total number of companies in the private sector in Japan

(Sugimoto 2003: 87),

5

the participants in this study represent the most

highly paid and privileged elite salarymen among all the salarymen in

Japan. Te type of companies varied from heavy industries to service

industries and brief biographies of the thirty-nine men are provided in

Appendix One. Particulars of the participants are provided in Appen-

dix Tree (Table One).

Te participants, who met the selection criteria were further divided

into three generations, loosely defned as Cohort One with age ranges

from sixty to eighty years, Cohort Two with age ranges from forty

to ffy-nine years and Cohort Tree with age ranges from twenty to

thirty-nine years. Tere is one blood-related pair of father and son in

this study, the father being in Cohort One and the son being in Cohort

Tree. Te way in which the participants are divided into the three

generations is arbitrary. Nevertheless, from an historical perspective,

each generation has its own distinctive traits in relation to masculin-

ity. Te men in Cohort One were born prior to the end of World

War Two, and their ideal masculinity in their childhood was unques-

tionably infuenced by the national propaganda of yamato-damashii

(the Japanese spirit in which one fulfls ones obligations and serves

the nation and the Emperor, sacrifcing oneself without fear of death);

5

Te proportion of employees who work for a company with more than 300

employees accounts for 11.4 per cent of the entire number of employees in frms in

the private sector (Sugimoto 2003: 87).

introduction 7

that is, the soldier spirit (Arakawa 2006a: 118; 2006b: 3738). How-

ever, shock waves and despondency in the nation, caused by losing the

battles in the Pacifc War, transformed Cohort One into kigysenshi

or corporate soldiers whose masculine missions assimilated rendering

services to the nation (once again) in order to reconstruct Japan. Tis

was demonstrated by the conspicuous economic successes that were

achieved during the period of high economic growth (195573). A

complicated set of sentimentsthe humiliation of Japans defeat in

the war and the envy of American afuenceafected the masculinity

of this generation. Te fact that Cohort One built an economic infra-

structure plays the major role in maintaining the unshakable mascu-

linity of this cohort.

Men in Cohort One were born between 1945 and 1964. Tey consist

of the so-called dankai or the baby boomers born between 1945 and

1950 and the post-dankai generations (Sakaiya 2005: 11). In the 1960s

and 1970s, when these men entered employment, the seniority-based

wage system, lifetime employment and company-based welfare system

were all well established in large corporations. Tese practices obliged

Cohort Two to become kaisha ningen (company men) who obediently

followed their companys demands. Te words wkahorikku (worka-

holic) and karoshi (death by over work) which appeared in the 1970s

and the 1980s respectively, symbolised the masculinity of Cohort Two

(and Cohort One) who were bound, hand and foot, to their compa-

nies and internalised the corporate ethos as part of their masculin-

ity, neglecting family life (Amano 2006: 2021). Te masculinity of

Cohort Two correlates with the collusive relationship between their

companies and the men themselves. Because of their mutual inter-

ests the mechanism with which the companies manipulated them into

devotion to work while they unconsciously exerted themselves to serve

their company was hardly questioned by either party. But as a result of

the bursting of the economic bubble in the early 1990s and its nega-

tive ramifcations, Japan is no longer a growing economic superpower.

Tis has allowed the cozy relationship between the company and its

workers to degenerate into a relationship that places high priority on

the companys survival over that of its employees. Yet the fact that

men in Cohort Two occupy important positions in their companies

indicates that hegemonic masculinity and the current gender rela-

tions in Japan have considerable bearing on their gender awareness

and behavioral patterns (Amano 2001: 31). Men in Cohort Tree who

were born between 1965 and 1984 fully enjoyed Japans afuence that

8 introduction

had been built, in their childhood, by Cohorts One and Two. Tis

Cohort, however, entered employment just before and afer the burst

of the economic bubble. As a result, while the masculinity idealised by

Cohorts One and Two lives on in the minds of Cohort Tree, they are

aware that their realitythe current economic slump, the companys

relentless restructuring and rationalism and the changing gender rela-

tions with the governments interventiondoes not secure an ideal

(gendered) life for them. Unlike Cohorts One and Two, whose hard

work had been sustained by the collective aspiration to rebuild the

nation and expand its economic empire, Cohort Tree does not have

the social or economic solidarity united by a common goal. Cohort

Tree works neither for the nation nor for their companies. Teir indi-

vidualised lifestyle is diferent from that of the older generations, and

this book provides a glimpse of the masculinity of that cohort, a cohort

on which further research is indispensable as there is a potential for

change in gender relations.

Tere were thirteen participants in Cohort One, ffeen in Cohort

Two and eleven in Cohort Tree. Te participants in Cohort One

were all married and had children. All the participants in Cohort Two

except one were married, with children, and among eleven partici-

pants in Cohort Tree, seven were married and four had children.

Feminist Methodological Considerations

Feminist methodology encourages the establishment of egalitarian

relationships between respondents and the researcher (Bloom 1998:

18; DeVault 1999: 31; Reinharz 1992: 21). Prior to the interviews, how-

ever, I was conscious of the possibility that I would not be able to

create an egalitarian relationship with my participants, especially with

men in Cohorts One and Two. In Japanese society, appropriate social

comportment entails particular language, including diferent forms of

politeness, and a demeanour according to ones social status, age and

gender. Tese change in accordance with the person to whom one is

speaking. At the time of the interviews, I was a female student who was

younger than the majority of the participants and whose focus was on

men, and not women. Accordingly, my personal circumstances, rather

than my circumstances as a researcher, afected the power dynamics

between each interviewee and myself. Tere were times when I was

daunted by inconsiderate remarks during the interviews and felt dis-

introduction 9

empowered despite my mental preparation for them. Of course, there

were also positive and empowering interviews, but these events that

occurred during the interviewsboth positive and negativetaught

me that structurally unequal power relations cannot be eliminated,

and that the researchers position in the power dynamics is not fxed,

depending also on inter-personal factors (Bloom 1998: 39). Power

oscillates between the participant and the researcher throughout the

interview process according to their subjective identity, their desires

and their life circumstances. As the relationship between the intervie-

wees and myself rarely allowed for an egalitarian situation, I would

suggest that our relationship was close to a professional interview

in which the researcher enters a persons life for a brief interview

and then departs (Plummer 1983: 139). However, as is evident in the

following chapters, the participants revealing or stark comments, or

their disclosure of intimate matters, demonstrated that the interviews

were not superfcial, which is something that might be suggested by

the term professional interview.

Given that feminist researchers who focus on women are women,

or who are generally expected to be women themselves, outsiders

usually means researchers who are not members of the researched

community, that is, male researchers (DeVault 1999: 2930; Stanley

and Wise 1993: 30; 1990: 21). Until recently, most feminist research

explored womens experiences and voices. In such situations, the

researchers identifcation with their respondents functions as a posi-

tive tool in interpreting womens stories and in gaining an insight

into the narratives (Bloom 1998: 18; DeVault 1999: 30; Reinharz 1992:

23). Yet, despite the adoption of feminist methodology, the focus of

my research was men. I was, therefore, an outsider in the community

of my respondents.

6

As Dasgupta (2005a: 54) discusses, I decided to

transform myself in order to establish a good rapport with my inter-

viewees. Firstly, I transformed myself from a student who wore casual

clothes into someone who dressed in relatively formal clothes, which

I speculated would be more agreeable to my participants dress code

standards. Secondly, I chose to use polite language or an honorifc

6

Layland (1990: 125), who is a feminist and in the middle of her research on gay

men, fnds her situation paradoxical. She even expresses her confusion as to whether

she is a feminist or not. However, she suggests that it is important to be conscious of

the situation and utilise the very feminist awareness in her research (Layland 1990:

132).

10 introduction

locution expressing the speakers humility in order to show my respect

for my participants, regardless of their social status and age. Neverthe-

less, my self in the symbolic interactions was altered and adjusted

according to the fow of the interviews. While an outsider in terms of

my age and gender, in a sociological or anthropological sense, I was

an insider because I was a Japanese person who understood Japanese

society, culture and language. Tis constitutes advantages for me over

non-Japanese researchers who are not familiar with Japan. Moreover,

as I used personal and family networks, those participants who knew

my friends, my family or my relatives welcomed me. Tis ofen took

the form of social activities outside the interviews. Since many of them

ofered their ofces as a venue for the interview I had, therefore, a

chance to visit their workplaces and join some of the participants for

lunch in a canteen at their company or in a nearby restaurant. Tese

events gave me wonderful opportunities for observation and for gath-

ering additional contextual information. For example, every time I

visited a company, a female worker served tea for me even in compa-

nies where tea and cofee vending machines were installed, and where

female workers would no longer be required to serve tea. However,

the diference from past practice was that the men had to ask a female

worker in advance to serve tea, giving the date, time and the number

of visitors (and in theory a female worker could refuse to oblige).

My difculties in developing egalitarian relationships with my par-

ticipants and my status as an outsider were by no means the total

impediments to my research. As will become evident in the follow-

ing fve chapters, the participants open discussion and self-disclosure

produced valuable interview material which was much more fruitful

than one might assume would arise from the relationship between a

young Japanese woman and salarymen who were usually older. In that

valuable material they expressed not only a sheer sense of security in

hegemonic masculinity but also vulnerability, confusion and regret.

Te Book

While the four gender dimensions in Connells gender theory consti-

tuted the analytical essentials of my project, allowing systematic analy-

sis of the research fndings within these four domains, it is difcult to

contain and analyse my research fndings within each domain because,

as Connell (2002: 68) clearly states, the four dimensions of gender

introduction 11

relations overlap and, therefore, they cannot be treated as separate

compartments of life. Because of these complicated and intertwin-

ing relationships within the four domains, while drawing on the four

gender structures, the order of the following chapters is organised in

accordance with the major phases of the mens lives, beginning with

childhood. Subsequent to this introductory chapter, fve chapters fol-

low. Chapter One explores the mens gendered experiences of growing

up as boys in their families. More specifcally, the chapter looks at their

relationships with their parents and siblings. Te chapter also explores

the theme of play. It examines their relationships with their peers in

settings such as the playground and the neighbourhood. Chapter Two

looks at the mens gendered experiences of growing up as male stu-

dents in their schools in relation to symbolism and peer culture. Tis

chapter also explores how physical education (PE) at school and sport

in club activities outside the school curricula afect the masculine iden-

tity formation of the participants. Chapter Tree deals with love and

marriage. Beginning with adolescence, a series of signifcant life events,

commencing with dating and culminating in marriage, is explored.

How the participants develop their sexual identity and what marriage

means to them are foci in this chapter. Chapter Four concerns work.

Tis chapter looks frst at the participants transition from education

to work. Secondly, it examines their perception of gender equality in

the workplace. Tirdly, it discusses transfersa painful price of being

a salaryman. Chapter Five is built upon the participants views of life,

focusing on ikigai (what makes life worth living) and parenting. Te

concluding chapter explores the post-retirement lives of the partici-

pants in Cohort Tree and sounds a warning about a contradictory

post-retirement life that other participants may have to face in the

future.

CHAPTER ONE

GROWING UP: GENDERED EXPERIENCES IN THE FAMILY

Segawa-san was born in Tokyo. His mother was sengy shufu (a pro-

fessional housewife) and his father was gdoman (a security guard).

He had a happy childhood until his brother was born. Because I was

an only child for fve years until my brother was born, so, in that sense,

I was lucky. For instance, especially my father used to buy me toys

and take me to various places. I think I received afection and special

treatment more than my brothers. By the time he reached his teens,

he sensed that there was something wrong with his family. As a matter

of fact, his mother and father were antagonistic, although there were

no hostile quarrels or domestic violence. Its a long story . . . I should

be honest, shouldnt I? My family, well, as a family, is a bit difer-

ent from other families. My family is diferent. Everyone did what-

ever they liked including my father and mother. My mother didnt do

housework regularly. My father was sort of the same. And they werent

on good terms. So I dont have happy family memories like going on a

picnic together or going to an amusement park together. My father did

his own shopping. So did my mother. My father ate what he bought

for himself. What my mother bought was hers. So, they never touched

the others food. Tere was no discipline at home. His parents lef

their children to care for themselves. My parents didnt teach me

manners. So I had to fnd out. How to put it . . . For example, when

I was in primary school, I didnt know how to behave when I went

to my friends houses. Because I didnt know what to do, I observed

what my friends were doing and, you know, I learned it. He used to

play with a girl next door when he was very small. If you ask me who

were my play mates, I would say that was a girl next door. What did

we do? I think we stayed inside and ofen played house. In due course

his family moved. He began to play with boys in the new place. He,

however, was always comfortable with girls. He enjoyed having a chat

with girls at school and they also seemed to be comfortable with him.

When he completed primary school, he was lef with one of his rela-

tives in Kysh, which was far away from Tokyo. He was still on good

terms with girls as friends. I dont think that I was conscious that I

14 chapter one

was talking to girls. I never thought if it was a boys conversation or

a girls conversation even during high school. However, boys in his

classroom made fun of him. He sometimes became a target of bully-

ing. He was sexually abused by one of his classmates. Ah, I wonder

if that was homosexual love or something else. I was in junior high

school. I had this friend. Well, I used to be bullied quite ofen at that

time and this boy took me to the toilet and touched me, frankly I

was at his mercy. Tis is my bitter memory. His adolescent homo-

sexual encounter still puzzles him in terms of understanding human

sexuality. His foster parents were very strict. I didnt play during high

school. Tey didnt let me go out. It was like school was the only place

I could enjoy myself when there were school events like a cultural

festival or something like that. He did well at school. He entered a

good academic high school and went on to university to study law,

in a faculty full of male students and male lecturers. Tis was what

his mother expected of him. My mother and my father had diferent

expectations of me. For example, my father had only compulsory edu-

cation. He wanted me to start working as soon as possible. He never

encouraged me to study. My mother, because I did well at school when

I was in primary school, she wanted to send me to a good school. He

gained freedom when he entered university. He enjoyed socialising

with friends. He had opportunities to go out on dates. However, he

had no idea how to approach his girlfriend. I couldnt have a relation-

ship nor even, you know, things like a date between a boyfriend and

a girlfriend. Even when I was in university, I wasnt good at it. Well,

I would go to a party and ask a girl to go for a drive on a weekend.

But then, on the day, I just dont know what to do . . . I was extremely

nervous and had no idea what to talk. He did not know how to move

on to the next step from friendship to a relationship.

Te above narrative is the growing-up story told by Segawa-san in

Cohort Tree, the youngest generation in this study. It is an unex-

pected and atypical picture of a salaryman, frstly because, as the pres-

ent chapter reveals, the majority of participants spent their childhood

in an unperturbed family that consisted of an employed father with

authority and a self-efacing mother who respected her husband. Sec-

ondly, almost all participants were immersed in homo-social male

friendships during their childhood. Tirdly, even participants in Cohort

One who were slow in developing relationships with women seemed

to proceed to relationships (or marriage) without much difculty (see

Chapter Tree). It is generally accepted in the Anglophone sociologi-

gendered experiences in the family 15

cal literature that the childhood family life, school life and adolescent

experiences infuence a mans gender identity (e.g. see Askew and Ross

1988: Ch.1; Connell 1995; Gilbert and Gilbert 1998; Pease 2002: Ch.4).

One might wonder, then, whether or not Segawa-sans parents mat-

rimonial circumstances, his congenial attitude to girls and his sexual

encounter afected his masculine identity. In fact, Segawa-san used to

regard himself (and still occasionally does) as efeminate because of

his good rapport with girls and he also felt that he was inappropriately

frail for a man because of his magnetism, and was as an easy target of

harassment by his peers.

In this chapter, I examine how childhood family relationships make

an impact on the construction of the masculinities of the participants

in my study. Te chapter looks at the family life of the participants in

connection, frstly, with the infuence of pre-war government policy:

the ie

1

system (the family system) and, secondly, with the state ideol-

ogy of rysai kenbo or good wife, wise mother; and, in the fnal sec-

tion, it also explores boys play in relation to peer culture.

Family: Te Ie System

Te assertion that womens lives in Japan refect the history of Japa-

nese policies in relation to global politics and economy (Liddle and

Nakajima 2000: 17) also has considerable bearing on mens lives in

Japan. Indeed, it was evident across the three generations of men in

my research that the infuence of the pre-war government policies

established in the Meiji period was still noticeable, to varying degrees,

in the course taken in their lives. Te rigid ideas that the longitudinal

or ancestral family transcends individual family members and contin-

ues in perpetuity and that the inheritance right of family business and/

or property belongs to a single successor, usually the frst-born son

of patrimonial lineage,

2

were stipulated in the old Civil Code (1898)

1

Te term ie is translated as household in English, although it is also understood

as family, house and genealogy according to the context. It is the fundamental social

unit in Japan. Te ie is a corporate body which owns the material, cultural and

social property of the household, runs and maintains a family business if there is one,

and continues the family line (Hendry 1981: 15; Kondo 1990: 121122; Ochiai 1996:

5859; Vogel 1971: 166).

2

While the inheritance right was not limited to men, an heiress was regarded as

merely a transit successor (take 1977: 240).

16 chapter one

established in the Meiji period and became known as the ie system

(Hendry 2003: 28; Hirai 2008: 6). While the ie system secured the

dominant position of men in both the privateas the kach (the

paterfamilias)

3

and the public spheres, women were legally incom-

petent (Hayakawa 2005: 249; Nishikawa 2000: 13). Te ie system was

abolished in 1947 because, under the new Civil Code, both husband

and wife were now treated as equal, for example, with regard to prop-

erty, parental power over children and inheritance (Supreme Court of

Japan 1959).

Yet despite the fact that the current Civil Code no longer conferred

patriarchal authority on men, the seemingly obsolete family system

overtly and covertly surfaced at various stages in the lives of the partic-

ipants. My research, conducted in the early twenty-frst century, also

revealed continuing practice of the ie system among my participants

(see Table Two in Appendix Tree) just as numerous other studies

between the 1950s and 1990s have found (e.g. Hamabata 1990; Hen-

dry 1981; Kondo 1990; Tsutsumi 2001; Vogel 1971; White 2002). Tis

is argued to be due to the propagation of the family system through

the educational system until the end of the war (Hendry 2003: 26;

1981: 15; Mackie 1995: 3). Te maintenance of the Koseki

4

(Family

Register) Law, in which the ofcial document of the family register

still retains an entry called the head of the family, has also preserved

the substance of the ie system in contemporary Japan (Iwakami 2003:

75).

5

Nevertheless, changes in and the decline of the ie system are

not denied. Families in Japan have been evolving through a chain of

eventsradical constitutional changes soon afer the Second World

War, the ensuing economic miracle, subsequent changes in the val-

ues of marriage and family, and urbanisation, globalisation and the

infltration of individualism. In the following section, the changing

practices of the ie system across the three cohorts in my study are

3

Te head of the ie had power to control his family members conditions and

welfare (Yamanaka 1988: 44).

4

Koseki is an ofcial document in which a married couple (or a single parent) and

their (her/his) single children of the same surname are recorded (Sakakibara 1992:

131). Before 1947, it registered the head of the family, his family members, their

relationships and the legal domicile (Iwakami 2003: 73).

5

Men accounted for more than ninety seven per cent of the entire register of the

heads of a family in the 1990s (Sakakibara 1992: 135137; Sugimoto 2003: 148) and

this has not changed to date. See also Arichi (1999).

gendered experiences in the family 17

discussed in relation to the authority of the head, the structure of the

family and relationships amongst family members.

Te waning of the ie system

In old times, if you were chnan (the frst-born son), you had to succeed

to ie. It doesnt matter if you have a noble family line or not. Defnitely,

[when I was small] I could sense the idea that the frst-born son had to

succeed. People and relatives implied it in a casual way. It was natural.

We didnt even need to be told the idea. (Ishida-san, I)

6

It was not surprising to fnd the traditional custom of the ie system

ubiquitous in the values and refections provided by Cohort One. Te

tradition of the ie systemthe continuation of the ie together with

flial pietywas in operation when participants in Cohort One, who

were born in the pre-war period, were growing up and continued in

widespread practice even afer the enforcement of the 1947 Civil Code.

All the participants in this generation, who married in the 1950s and

the 1960s, were aware of the basic rules of the ie system. In the eyes

of the participants, it was obvious that someone had to succeed to the

ie. Amongst the thirteen participants of this generation, there were

three frst-born sons. One of them, Katagiri-san, was adopted into a

wealthy couple who were his mothers sister and her husband and had

no children. Tis was when he was very small and just afer his father

had died on the battlefeld. Te fact that his sister remained with his

biological mother implied that the couple chose Katagiri-san because

he was a male. As he was the only child of his foster parents, he suc-

ceeded to their house and tended them at home until they passed away.

While another participant, Sonoda-san, always lived with his parents

and looked afer them, the house where he was born was destroyed by

an air raid in 1945, and this explains why he did not succeed to the

parental home.

Te responsibility for fulflling flial piety places a heavy burden on

family members, especially on the womeni.e. the wives

7

because

6

I indicates Cohort One.

7

See Long (1996) and Jenike (2003) for Japanese womens stressful experiences

in caring for the old and Lebra (1984) for married womens relationships with

mothers-in-law, but see also Harris, Long and Fujii (1998) for possible changes in

the contemporary care-giving activities in which the involvement of husbands and

sons in the care of their wives and parents might increase due to the combination of

increasing life expectancy and the lack of public care.

18 chapter one

it is the women who do all the physical labour of care while their

husbands are busy working. In the course of the interview Katagiri-

san expressed gratitude to his wife for services which she rendered to

his bedridden mother, ranging from feeding her and attending to her

personal needs, changing her nightclothes. I could sense his sincere

gratitude as, during the interview, Katagiri-san never expressed such

appreciation of his wife in other areas, such as housework and par-

enting. In contrast to Katagiri-san, Sonoda-san is unusual. He made

eforts to attend to his sick mother at home as much as possible. He

asked his company for permission to start work at nine oclock, which

was later than the normal starting time at workplaces. In addition, he

came home to care for her during lunchtime. Sonoda-sans father had

died of cancer much earlier than his mother. He had also lost his frst

wife when his daughter was small and his mother had taken care of the

household (and did so even afer Sonoda-san married again). Because

of his deep feelings for his mother, he wanted to look afer her. Only

Hirose-san, among the frst-born sons, did not follow the tradition of

succeeding to the parental home and living with his parents; however,

he lived close to his parents throughout his adult life.

Te families into which the other ten, non-frst-born participants

were born, also followed the ie system. Te oldest brothers of eight of

these participants succeeded to their households, while the parents of

the other two participants, who were not blessed with healthy frst-born

sons, transferred their households to other sons. Tus the participants

in Cohort One endorsed the common practice of the continuation of

ie by a single (frst-born) son and heir.

My brother has a tacit understanding that he will look afer our parents.

He doesnt live with our parents but he lives only 100 metres away from

our parents house. (Hino-san, II)

8

Amongst participants of Cohort Two, who grew up in the period of

high economic growth, the ie system diminished somewhat. Although

they were conscious of the system and they assumed that generally the

frst-born son succeeded to the ie, the participants of this cohort were

concerned mainly about the care of their ageing parents rather than

the continuation of their ie. Of ffeen participants, there were eight

frst-born sons. Amongst them, only Tachibana-san lived in the house

8

II indicates Cohort Two.

gendered experiences in the family 19

where he had been born. Tachibana-sans parents had been adopted

at marriage into a distinguished family, which was a descendant of a

respected samurai family, but who had no son.

9

Accordingly, Tachi-

bana-san succeeded to the ie as the head of the family line. Two other

participants, Sugiura-san and Toda-san, lived with their parents but

not in their parents houses. When they set up their own households,

they invited their parents to live with them.

Living with parents-in-law involved both advantages and disadvan-

tages for wives in Cohort Two. Sugiura-sans wife enjoyed full-time

paid work, as her spry mother-in-law looked afer the household, while

Toda-sans wife was bound to the care of her own bedridden mother

as well as her in-laws. Toda-sans case was unusual because he lived

with his own parents as well as his wifes mother, as his wife had no

male siblings, indicating the shif in emphasis in this generation from

inheritance of property to a focus on caring for ageing parents. It was

generally considered to be the wives responsibility to look afer elderly

parents-in-law at home. Indeed, Sugiura-san was prepared for the care

of his parents, which meant that it is very likely that his wife will have

to look afer her in-laws in the future, unless there is a signifcant

increase in government support for the care of the elderly (Izuhara

2006: 166; Long 1996: 171).

Because of the pattern of economic growth, fve frst-born sons had

moved away from the locality of their parents houses in order to work

for large companies in a big city. Even so, they accepted their responsi-

bility for flial piety as the frst-born son. Yoshino-san resigned his frst

job and returned to his hometown, not only because he wanted to go

back to his birthplace but also because he was worried about his ageing

parents. Matsuzaki-san was concerned about the care of his parents

grave when he died. Ono-san, who had been transferred from place to

place for work, asked his company to transfer him to his hometown

when his retirement was approaching. He also wished to care for his

parents grave because flial piety necessarily involves care of the grave

and semi-permanent ceremonial events, according to the particular

faith. Likewise, other frst-born sons, including the participants and the

oldest brothers of other participants, as the above quotation indicates,

9

Tere was another example of the adoption of a married couple. Ueno-sans

parents were adopted at their marriage by one of their relatives who had a family

business to continue but no children. Ueno-sans older brother succeeded to the ie

and to the business.

20 chapter one

lived close to their parents to help them in the event of an emergency.

10

Teir concern may have been generated either by the parents strong

desire to live together with their son or by a sense of responsibility felt

by frst-born sons without any explicit claims having been made by

their parents. As an example of the frst situation, Toda-sans parents

always expressed their expectation that they wanted him to look afer

them in their old age. On the other hand, Yoshino-san returned to his

hometown to live close to his parents without being told to do so by

his parents. Unlike the above participants, Sugiura-san told me with a

hint of ambiguity that:

As a frst-born son, I realised its responsibility just before the university

exam. You know, I thought Ill have to take care of my parents afer all.

Because, when my grandfather got ill, my father decided to take care of

him and brought him to our house. I saw it just before the exam. Tats

why I got that thought. I thought I wont be able to go far away from

home. I shouldnt have thought that way but since then, Ive never got

real courage [to go against the responsibility]. I was seventeen or eigh-

teen when your anxiety is running high. (Sugiura-san, II)

Sugiura-sans feelings suggest that the fulflment of flial piety arises

from the coercive nature of the ie system that compels the prac-

tice of respect from successors for their parents and ancestors (Kondo

1990: 141). He admitted that since then he never had the courage to

go against the responsibilities associated with being a frst-born son.

Nevertheless, it is by no means an emotionless outcome. To be a duti-

ful son satisfes the above participants in feeling proud that they are

conducting themselves as respectable and responsible men. In either

case whether forced or spontaneous, the sons concern was not the

continuation of their ie but the fulflment of the duties of flial piety.

In Cohort Two, the ie system no longer functions institutionally with

regard to inheritance but it survives in the sense of obligation felt by

many frst-born sons.

Te operation of the ie system further diminished in the youngest

generation, Cohort Tree, who were men born in the stable economic

period. It is reasonable to suppose that the parents of participants

in this generation are younger and currently enjoy good health; and

therefore, that caring for their parents in their old age is not an immi-

10

Te results of National Family Research 98 (NFR 98) also support this tendency.

See Tabuchi and Nakazato (2004: 129).

gendered experiences in the family 21

nent issue for participants of this generation. Nevertheless, the par-

ticipants showed little consideration for flial piety and revealed their

parents lower expectations of it than among the older generations.

For example, Ebara-san mentioned that:

My father has never said anything about the succession. I guess his true

feelings were that he wanted me to help him and succeed to his busi-

ness. I wonder what his intention is now. I believe hes given up on me.

(Ebara-san, III)

11

As the above quotation indicates, Ebara-sans self-employed father

seemed to be resigned to the fact that his son would not succeed

him. Likewise, Okano-sans father, who was also self-employed, never

expected Okano-san to take over the thriving family business. Further-

more, the participants were unconcerned about fulflling their parents

expectations:

Actually, Im sure my father wants to chase his dream of expanding

his business and he wants this to be my dream because he doesnt like

the idea that his business will end in his lifetime. But neither I nor my

younger brother are not going to succeed. (Kusuda-san, III)

Kusuda-sans father openly asked him to succeed to the family busi-

ness. Even so, Kusuda-san had no intention of meeting his fathers

expectations. Moreover, Kusuda-sans mother supports his position

and implicitly opposed her husband. According to Kusuda-san, his

mother appreciated the fact that working for a large company pro-

vided her son with a stable income, regular work time and company

welfare benefts, which were better for him than the arduous and

strenuous family business. Indeed, and for the same reasons, one-third

of mothers in Cohort Tree, reportedly encouraged the participants,

when they were small, to become a salaryman in a decent company.

Despite the fact that nine out of eleven participants were frst-born

sons, none of them was conspicuously concerned about the con-

tinuation of their ie or flial piety. Despite the wishes expressed by a

handful of their parents, particularly fathers, no participant in Cohort

Tree had taken over family businesses. Part of the explanation lies in

changes in the Japanese economy. A considerable number of family

businesses, which have been sustained by the ie system, have been in

decline (Rebick 2006: 76), whereas men in Cohort Tree have largely

11

III indicates Cohort Tree.

22 chapter one

sought secure salaryman employment, which ofen means relocating

to large cities. Tere has thus been a growing incompatibility between

practicing the ie system and becoming a salaryman. But much of the

explanation lies in changing values. Te participants of Cohort Tree

tended to pursue their own aspirations with little consideration for the

ie system. In addition, their mothers encouraged this tendency in their

sons, indicating that a celebrated manly path has shifed from owning

a family business to entering a corporation. However, it is of course

uncertain whether or not attitudes of young men in Cohort Tree

towards their parents will change as they grow older. Te participants

understood their parents to be resigned to declining flial piety among

the younger generations. Te resignation facilitated by their parents

fnancial resources also enabled their sons to follow their own desires

more freely (Raymo and Kaneda 2003: 30).

Te survival of the ie system

Te diference between men and women is that, defnitely, men have a

higher position than women. Terefore, women, even if they are parents,

cant go over mens heads. Tat was the rule at home. We were told

women shouldnt go over mens heads but men can. (Ueno-san, II)

While the inter-generational aspects of the ie system appear to be on

the wane, patriarchal relations based on gender and age have been

more resistant to change. Almost all the participants remembered

a childhood in which the authority of the father as the head of the

family was clearly visible. A signifcant aspect of ie is that the system

grants the paterfamilias power over his family, although in the post-

war period this power has had a more symbolic basis rather than a

legal one. Moreover, the power of paterfamilias was transformed into

the power of father/husband in the modern family (Ueno 1994: 76).

Te fathers dominant position was expressed both in family rules and

special treatment given to fathers. For example, the majority of fathers

of the participants in every generation were given the seat of honour

called kamiza or yokoza at the head of the family table (see Ueno 2004:

42; 2002: 101):

My father sat at the top of the table. Te TV was in that room and his

seat was the best position to watch TV. Its like this. Boys sat on both

sides close to him and next to them sat the girls. (Kusuda-san, III)

gendered experiences in the family 23

Te fathers seat was normally fxed and situated in the best position

to watch television and participants fathers chose the programmes

to watch,

12

regardless of cohort, the only exception being some fami-

lies in the Cohort One who did not have television in their homes as

television only came into widespread use in the middle of the 1960s

(Nakamura 2004: 49). In all three cohorts, sons generally occupied

seats that were closest to their fathers. Daughters took seats next to

their male siblings. Mothers sat in the seats that were the nearest to

the kitchen. Another narrative of symbolic seating came from Ono-

san (Cohort Two). When his family had meals around irori (an open

hearth), his mother sat in a place where smoke issued from the hearth.

Like Ono-san, no participants seemed to have questioned the seating

arrangements at home. Some participants indicated that their fathers

authority also manifested itself in other ways. Honda-san (Cohort

One) remembered that his family members were not allowed to start

eating until his father began to eat. Uchida-san (Cohort One), Ueno-

san (Cohort Two) and even Shimizu-san (Cohort Tree) said that

their fathers had an additional dish at dinner, e.g. sashimi (raw fsh).

Furthermore, many fathers took a bath frst (see Hendry 1981: 89).

In extended families, Hino-sans grandfather took a bath frst, while

Yoshino-sans grandmother took her bath frst only because his father,

showing flial piety, insisted that she do so. Te male siblings usually

took their baths before their female siblings did. Tis patriarchal order

lasted until the participants became busy with their school life and

it became impossible to maintain it. Not surprisingly, mothers were

ofen the last to use the bath. Tese practices implied that the fathers

were held in high esteem and that the mothers were placed in a servile

position.

No participants in any of the cohorts expressed antipathy to their

fathers authority. However, the way in which they interpreted their

closeness to (or distance from) their father varied. Participants of

Cohort One, as the quotation below indicates, stood in awe of their

fathers and respected them for their dignity as a father and as a man:

12

Tis has also been found for a study in the U.S. See Walker (2001).

24 chapter one

What parents say is as sacred as what god says. In the old days, we used

to say earthquakes, thunder, fre and fathers.

13

My father was the scari-

est person for me. (Shiga-san, I)

Much respectful talk concerning how interesting, intelligent and hard-

working their fathers were came from participants of this generation.

Compared with the younger generations, participants whose child-

hood occurred prior to the period of high economic growth were

relatively close to their fathers and had a good understanding of them

(except for those participants whose fathers went to war).

14

Tey com-

municated with their fathers and shared activities in their daily lives,

ofen helping them with their work in a feld or work-room. On the

other hand, the mothers of the participants were much less visible in

the background.

Participants in Cohort Two did not boast about their fathers. Tese

fathers plunged into long hours as salarymen who delivered high eco-

nomic growth but who grew distant from their sons. Sugiura-sans

father, who worked for an iron-manufacturing company, was ofen

absent from home. Tachibana-sans father came home later and later

as his social drinking hours extended. Yoshino-san and Kuraoka-

san saw their self-employed fathers working from early morning till

late at night, ofen until eleven oclock. As a result, participants in

Cohort Two indicated an emotional chasm between themselves and

their fathers. Tey also criticised their fathers, although not for their

long working hours, but for failures in their fathers personalities, for

example, in being narrow-minded. As the presence of fathers dimin-

ished, the presence of mothers in the memories of men in this cohort

increased slightly. As Sugiura-san remembers:

I was scared of my mother. She is gentle now, though. [She was strict]

because my father was absent from home. She just kept beating me. I

think she was stressed and tense because she and my father [who came

from a small town] had to do everything all by themselves in a big city,

like rearing children and buying a home. I think they were extremely

tense. . . . Tats how I see it. (Sugiura-san, II)

13

Shwalb, Imaizumi and Nakazawa (1987: 248) argue that this saying indicates

that the traditional defnition of the father was as an awe-inspiring authority fgure,

almost as fearsome as natural calamities such as earthquakes.

14

Fathers were close to their children prior to Japanese industrialisation because

the fathers involvement in housework, childcare and childrens education in the

Tokugawa and Meiji periods was greater than that afer industrialisation (Muta 2006:

81; Uno 1993b: 51; 1991: 25).

gendered experiences in the family 25

Likewise, Toda-san remembered his mother standing in front of the

gate with a broom in her hand when his sister failed to come home

by curfew. Tese mothers were strict moral disciplinarians on behalf

of their absent fathers.

In Cohort Tree, mothers again disappeared into the background,

while fathers were represented as strict disciplinarians. Despite the

common acceptance of household privileges of the father as the head

of the ie, the term for a domineering husband, teishukanpaku, was

used by several participants in this cohort to describe their fathers.

Tis term was not used in the older generations and suggests that the

patriarchal family head is becoming a more contested position in Japa-

nese society. A domineering husband is seen as less typical and unde-

sirable in the youngest generation in this study:

My father is teishukanpaku . . . he is obstinate most of the time. Well, my

mother is good. She is not dissatisfed. She just obeys my father. Tey

are on very good terms with each other. But, you know, well, my mother

thinks they are fne but I think my father should be a bit more coopera-

tive because I dont think every father should be domineering, should

they? Terefore, in this sense, he is hanmenkyshi (a person who serves

as an example of how not to behave). (Shimizu-san, III)

Shimizu-san criticised his domineering father and showed sympathy

for his submissive mother, although he still described his mothers

long-sufering obedience in admirable terms. Okano-san also described

his father as very sexist and an advocate of danshi chb ni tatsu beka-

razu (men shall not enter the kitchen).

15

Okano-san admitted that his

fathers infuence on his view of gender was considerable. He revealed

that he used to behave like his father in front of his ex-girlfriends.

However, he felt that his attitudes scared them and afer a series of

breakups in relationships, he decided to change his sexist attitudes

towards women. Te partner of Okano-sans sister, a European man,

who appeared to him to be diferent from conservative Japanese men,

also triggered his attitudinal change. Te only exception was Kusuda-

san who had a very close relationship with his self-employed father,

with whom he spent a considerable amount of time communicating

and sharing the traditional ideas about gender roles. In the abstract, he

15

Japanese people tend to think that the phrase represents Japanese tradition;

however, there is a record that men in the Sengoku period (13921573) (the Age

of Civil Wars) did the cooking. Even men in the upper class enjoyed cooking (It

2003: 25).

26 chapter one

said, men work outside, for example they build a house, while women